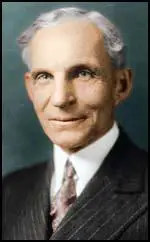

Henry Ford

Henry Ford, the second of eight children, son of William Ford (1826–1905) and Mary Litogot Ford (1839–1876), was born in Greenfield, Michigan on 30th July, 1863. He was the grandson of John Ford, a Protestant tenant farmer who had come to America from Ireland during the great potato famine of 1847. (1)

William Ford had a farm of eighty acres. According to Henry's biographer, Andrew Ewart: "He showed an early facility for repairing clocks and watches but at home on the farm he had to take his share of the inevitable chores, chopping wood, milking cows, learning to harness a team of horses. When he was twelve he was ploughing and doing a man-sized job on the farm. He had no education in science - he got his considerable mechanical knowledge from experience." (2)

Ford was very close to his mother and was devastated when she died when he was only thirteen. In 1879, against the wishes of his father, he moved to Detroit where he found work at the James Flowers Machine Shop. He was assigned to mill hexagons onto brass valves. Ford was pleased to be away from his father and grandfather. He later wrote, "I never had any particular love for the farm - it was the mother on the farm I loved." (3)

Within a year he had moved to the Detroit Dry Dock Engine Works, the largest shipbuilding firm in the city. He worked a sixty-two-hour week in a machine shop, while, to earn a bit extra, repairing watches in a jewellery store six nights a week as well. Later he travelled round Michigan farms servicing Westinghouse steam engines. (4)

At this time Detroit was a city that offered plenty of opportunities of work. It had a population of more than 116,000 people, covering an area of seventeen square miles - an industrial, shipping, and railroad hub with nearly 1,000 manufacturing and mechanical establishments, twenty miles of street railways, a telegraph network, and a waterworks. (5)

On the death of his grandfather he returned to help his father manage the family farm. He was also given 40 acres to start his own farm. In 1886 Henry Ford met Clara Bryant, the twenty-year-old daughter of a local farmer. He told his sister Margaret that in thirty seconds that he knew this was the girl of his dreams. In April 1888 Henry married Clara, who was three years younger than himself. (6)

During this period Ford read an article in a magazine about how the German engineer, Nicholas Otto, had built a internal combustion engine. One night, after returning from repairing an Otto engine that belonged to a friend, he told his wife that he intended to build a "horseless carriage". Ford disliked farming and spent much of the time trying to build a steam road carriage and a farm locomotive. (7)

Henry Ford and the Petrol Engine

In September, 1891, he returned to Detroit to work as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company. The couple moved into a two-story house, a short walk from the works. Ford was extremely ambitious and eventually became chief engineer at the plant at a salary of 100 dollars a month. Soon afterwards, on 9th November, 1893, his son and only child, Edsel, was born. (8)

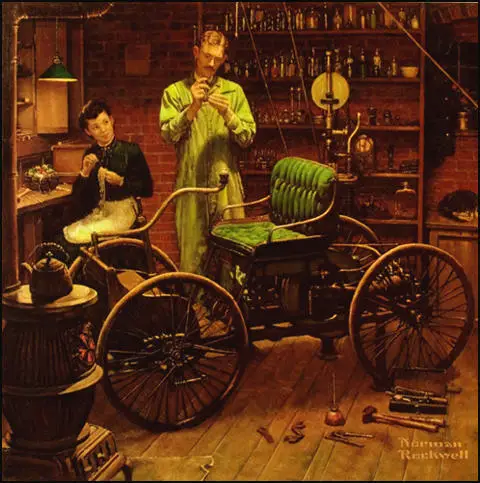

His first vehicle, called a Quadricycle, was finished in June 1896, was built in a little brick shed in his garden. "With a two-cylinder petrol engine, a bicycle seat, a wooden chassis and bicycle tyres on its spindly wheels, it was steered by a tiller and had a house bell as a horn. It weighed only 500 pounds and had a top speed above 20mph, though rival machines rarely exceeded 5mph. Embarrassingly, the completed Quadricycle was too big to get out through the door of the shed and Ford had to demolish part of the wall with an axe." (9)

.

Two months later Henry Ford attended a meeting of members of the National Association of Edison Illuminating Companies in the Oriental Hotel in Brooklyn. At the meeting, Ford's boss, Alexander Dow, introduced him to Thomas Edison with the words: "Young fellow here has made a gas car." Edison was curious and began to pepper Ford with detailed questions. Ford drew a picture of his machine on a scrap of paper. Edison was impressed and told him to "keep at it!" From that moment onward, Ford's admiration ripened into hero worship "like a planet that had adopted Edison for its sun." (10)

Henry Ford carried on with his job at the Edison plant while he set about designing and building his second car. However, he was told by his bosses: "You can work on your car or you can work for us - but not both." Ford now approached a group of businessmen to fund the venture. He was originally given $15,000 to build ten cars. Ford established the Detroit Automobile Company and was determined that cars would be as near perfect as he could make it and insisted on improving the carburation system. His refusal to put the car into production until he was satisfied with it, infuriated investors. After spending $86,000 ($2.15 million in today's money) on the project the company collapsed in January 1901. (11)

.

Ford decided to establish himself with the public by building a racing car. He challenged, Alexander Winton, the most famous racing driver of the day, to a race at Grosse Pointe. Ford won an event styled "the first big race in the west" by almost a mile. Ford later recalled: That was my first race, and it brought advertising of the only kind that people cared to read." After this he had no trouble in raising the money to start a new company. On 23rd November, 1901, Henry Ford sold 6,000 shares at a par value of ten dollars each. (12)

By this time there were several other companies manufacturing cars. Ford suffered from production delays, and this caused conflict with his shareholders and once again the company collapsed. Disillusioned by his lack of success in producing motor cars for the road and decided to return to racing cars. The first one, The Arrow, crashed during a race in September 1903, killing its driver, Frank Day. His second car, Ford 999, driven by Barney Oldfield, was a great success. On 12th January, 1904, Henry Ford drove the 999 to a speed of 91.37 mph (147.05 km/h). (13)

.

Ford recruited Oliver E. Barthel, a talented young mechanic and engineer. He later recalled that “Henry Ford was a cut-and-try mechanic without any particular genius.” He was also concerned about what he considered to be Ford's dual nature: "One side of his nature I liked very much and I felt that I wanted to be a friend of his. The other side of his nature I just couldn't stand. It bothered me greatly. I came to the conclusion that he had a particular streak in his nature that you wouldn't find in a serious-minded person." (14)

Ford Model T

Alexander Malcolmson, a coal dealer in Detroit, was very impressed with the Ford 999 and decided to make a substantial investment in Henry Ford. The partnership began in August 1902. He also persuaded some of his friends to back Ford and by June, 1903, there were twelve stockholders who between them had raised $28,000 in cash to float the company. Ford and Malcolmson owned over 50% of the company. (15)

As a result of Ford's earlier problems, Malcolmson installed his clerk James Couzens at Ford Motor in a full-time position. Couzens borrowed heavily and invested $2,500 in the new firm. Ford Motor Company was founded in 1903 with John Simpson Gray as president, Ford as vice-president, Malcolmson as treasurer, and Couzens as secretary. Couzens took over the business management of the new firm for a salary of $2,400. (16)

The Ford Motor Company was only one of 150 automobile manufactures that were active in the United States. Ford now set about making what became known as the Model T (also known as the Tin Lizzie or Leaping Lena). He told his investors: "I will build a car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God's great open spaces." (17)

A petrol engine patent was granted in 1895 to George Baldwin Selden. Therefore all car manufacturers were required to pay royalties to the lessee of the patent. To protect themselves these manufacturers had formed an association and had arranged with the lessee of the patent, the Electric Vehicle Company, to control the industry. Ford refused to join the organisation and instead challenged the validity of the patent. (18)

The first Model T car left the factory on 27th September, 1908. The first cars were assembly by hand, and production was small. Only eleven cars were built during the first month of production. It was sold for $825 and this made it the cheapest in the market. Early sales were very encouraging. Ford also introduced the latest marketing methods. His publicity department ensured that newspapers carried stories about the Model T. In 1909 Ford produced 10,600 cars and that year his company made a profit of over a million dollars. According to William Davis, the "Model T had two undeniable merits: it was efficient and it was cheap. Ford's innovative concept was a reliable car that would sell for no more than the price of a horse and buggy." (19)

Since 1908 Ford had spent around $2,000 a week defending himself against the other car manufacturers. In 1910 the court upheld Selden's patent. The verdict could have put him out of business. However, he now appealed to a higher court: "It is said that everyone has his price, but I can assure you that, while I am head of the Ford Motor Company there will be no price that would induce me to add my name to the association." Dealers were warned not to sell his "unlicensed cars". Times were very difficult for Ford until the United States Court of Appeals gave out its verdict completely upholding all his contentions with regard to the patent. (20)

Sales were so good that his Piquette Plant could not keep up with demand. Ford therefore decided to move his operations to the specially built Highland Park Ford Plant. Over 120 acres in size it was the largest manufacturing facility in the world at the time of its opening. In 1913, the Highland Park Ford Plant became the first automobile production facility in the world to implement the assembly line. (21)

Ford had been influenced by the ideas of Frederick Winslow Taylor who had published his book, Scientific Management in 1911. Peter Drucker has pointed out: "Frederick W. Taylor was the first man in recorded history who deemed work deserving of systematic observation and study." (22) Ford took on Taylor's challenge: "It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone." (23)

.

Initially it had taken 14 hours to assemble a Model T car. By improving his mass production methods, Ford reduced this to 1 hour 33 minutes. This lowered the overall cost of each car and enabled Ford to undercut the price of other cars on the market. By 1914 Ford had made and sold 250,000 cars. Those manufactured amounted for 45% of all automobiles made in the USA that year. (24)

On 5th January 1914, on the advice of James Couzens, the Ford Motor Company announced that the following week, the work day would be reduced to eight hours and the Highland Park factory converted to three daily shifts instead of two. The basic wage was increased from three dollars a day to an astonishing five dollars a day. This was at a time when the national average wage was $2.40 a day. A profit-sharing scheme was also introduced. Unfortunately, the women working at the plant remained on two dollars a day. (25)

Henry Ford took the credit for this bold move calling it "the greatest revolution in the matter of rewards for workers ever known to the industrial world." (26) The Wall Street Journal complained about the decision. They accused Ford of injecting "Biblical or spiritual principles into a field where they do not belong" which would result in "material, financial, and factory disorganization." (27)

Ford rejected the criticism that it was a publicity stunt. "To our way of thinking, this was an act of social justice, and in the last analysis, we did it for our own satisfaction of mind. There is a pleasure in feeling that you have made others happy - that you have lessened in some degree the burdens of your fellow-men - that you have provided a margin out of which may be had pleasure and saving. Good-will is one of the few really important assets of life. A determined man can win almost anything that he goes after, but unless, in his getting, he gains good-will, he has not profited much." (28)

The company also established the Ford Sociological Department, headed by John R. Lee, "a man of ideas and ideals with a keen sense of justice and a sympathy with the 'down and outs', the men in trouble, that leads to an understanding of their problems... Under his guidance, the department will put a soul into the company". Ford also appointed the Reverend Samuel S. Marquis as his spiritual adviser. Ford told him that "I want you to put Jesus Christ in my factory". He added that the teachings of Jesus Christ were "the basis upon which a new society must be built". (29)

The Sociological Department had a staff of more than fifty investigators, that grew to a force of 160 men within two years. The investigators, chosen because of their "peculiar fitness as judges of human nature" were an "odd hybrid of social worker and detective, venturing into the crowded back streets of the city with a driver, an interpreter, and a sheaf of printed questionnaires. Their job was to establish standards of proper behaviour throughout the company." One member of the department said that it "was necessary in order to teach the men how to live a clean and wholesome life." (30)

To qualify for the five dollar a day, an employee had to put up with an exhaustive domestic inspection. If an investigator discovered a Ford employee was living with a woman without going through a marriage ceremony, an application was made to the Probate Court, so their union could be legitimized. Ford, who considered himself to be "highly moral and upright" did not drink alcohol or use tobacco in any form (he considered cigarettes as "little white slavers"). If a Ford worker was determined by Sociological Department investigators to be "immoral" they were offered the opportunity for rehabilitation so that he could be "lifted up" to the requirements of the company. Then and only then would he be certified to receive Ford's "bonus-on-conduct". (31)

William Davis has pointed out that although he paid high wages Ford was totally against trade unions: "He (the Ford worker) had to produce. Ford's assembly line saw to that. It had no place for men who needed to go to the toilets during shifts; such weaklings were weeded out as soon as discovered, and other men were paid to discover them. He was implacably against labour unions, which would interfere with his manufacturing methods." (32)

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War in Europe, Ford soon made it clear he opposed attempts to persuade America to become involved in the conflict. He gave an interview to the New York Times on the war: "Moneylenders and munitions makers cause wars; if Europe had spent money on peace machinery - such as tractors - instead of armaments there would have been no war... The warmongerers urging military preparedness in America are Wall Street bankers... I am opposed to war in every sense of the word." (33)

Ford also made it clear that he would not be lured into the convenient economic trap of becoming a war-dependent manufacturer. He told the New York American Journal in August, 1915: "I would never let a single automobile get out of the Ford plant anywhere in the world if I thought it was going to be used in warfare." According to Ford, war was "a wasteful sacrifice" pushed forward by "avaricious, amoral arms makers". (34) Ford announced: "I hate war, because war is murder, desolation and destruction... I will devote my life to fight this spirit of militarism." (35)

Ford supported the decision of the Woman's Peace Party to organize a peace conference in Holland. After the conference Ford was contacted by America's three leading anti-war campaigners, Jane Addams, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Paul Kellogg. They suggested that Ford should sponsor an international conference in Stockholm to discuss ways that the conflict could be brought to an end. Rozika Schwimmer, a campaigner from Budapest, was sent to talk to Ford. (36)

Ford came up with the idea of sending a boat of pacifists to Europe to see if they could negotiate an agreement that would end the war. He agreed to spend $500,000 to rent the Oskar II, and it sailed from Hoboken, New Jersey on 4th December, 1915. On board the ship Ford told Rozika Schwimmer: "I know who started the war - the German Jewish bankers." Some writers have speculated that Ford did not realise that Schwimmer was Jewish. It has been argued that Schwimmer was diplomatic enough to avoid confronting Ford directly on his views. (37)

The Ford Peace Ship reached Oslo on 20th December, 1916, and a conference was organized with representatives from Denmark, Holland, Norway, Sweden and the United States. However, Ford, who had been taken ill on the journey, did not take part in the public events after the ship docked. Unable to persuade representatives from the warring nations to take part, the conference was unable to negotiate an Armistice. Most newspapers attacked Ford's efforts but the New York Herald Tribune asserted that, "We need more Fords, more peace talks, and less indifference to the greatest crime in the world’s history". (38)

Ford continued to argue that: "Industry must manage to keep wages high and prices low. One's own employees should be one's own best customers." Five of his five stockholders took him to court to force him to distribute the company's earnings. Ford told the court that the profits of the Ford Motor Company were neither his nor the stockholders. Ford told the court that the profits of the Ford Motor Company were neither his nor the stockholders. "After the employees have had their wages and a share of the profits, it is my duty to take what remains and put it back into the industry to create more work for more men at higher wages." (39)

.

In 1920 Ford had bought out all his minority stockholders and it became a family property. By 1926 he had quadrupled the average wage to nearly $10 and the price of the Model T had fallen to only $350. Alistair Cooke, the author of America (1973) pointed out: "It is staggering to consider what the Model T was to lead to in both industry and folkways. It certainly wove the first network of paved highways, subsequently the parkway, and then freeway and the inter-state. Beginning in the early 1920s, people who had never taken a holiday beyond the nearest lake or mountain could now explore the South, New England, even the West, and in time the whole horizon of the United States. Most of all, the Model T gave to the farmer and rancher, miles from anywhere, a new pair of legs." (40)

Henry Ford and Anti-Semitism

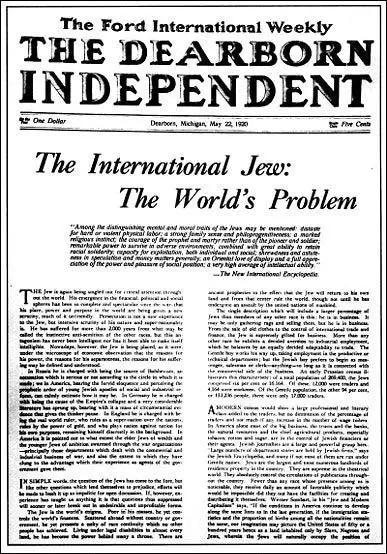

At the end of the 1918 Ford purchased the Dearborn Independent. He told the readers: "I am very much interested in the future not only of my own country, but of the whole world, and I have definite ideas and ideals that I believe are practical for the good of all and I intend giving them to the public without having them garbled, distorted or misrepresented." He also announced that he was willing to spend $10 million to finance the publication." He told the editor that he did not want any mention of Ford's industrial enterprise. Unlike most newspapers, it carried no advertisements. In 1919 he told the New York World: "International financiers are behind all war. They are what is called the international Jew: German-Jews, French-Jews, English-Jews, American-Jews... a Jew is a threat."

Ford did not write all the articles in the newspaper. The editor, William Cameron, a passionate anti-Semite, is thought to have written most of it. Ford's secretary, Ernest Liebold, stated that "the Dearborn Independent is Henry Ford's own paper and he authorizes every statement occurring therein. Liebold added: "The Jewish question, as every businessman knows, has been festering in silence and suspicion here in the United States for a long time, and none has dared discuss it because the Jewish influence was strong enough to crush the man who attempted it. The Jews are the only race whom it is 'verboten' to discuss frankly and openly, and abusing the fear they have cast over business, the Jewish leaders have gone from one excess of the other until the time has come for a protest or a surrender."

On 22nd May, 1920, the Dearborn Independent included an article with the headline, "The International Jew: The World's Problem". The first paragraph began: "There is a race, a part of humanity which has never yet been received as a welcome part." The article went on to argue that in order to eventually rule the Gentiles, the Jews have long been conspiring to form an "international super-capitalist government." As James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979), has pointed out: "In subsequent articles, Ford frequently accused the Jews of causing a decline in American culture, values, products, entertainment, and even worse, of being the instigator of World War I."

In another article Ford argued: "The Jew is a race that has no civilization to point to no aspiring religion... no great achievements in any realm... We meet the Jew everywhere where there is no power. And that is where the Jew so habitually... gravitate to the highest places? Who puts him there? What does he do there? In any country, where the Jewish question has come to the forefront as a vital issue, you will discover that the principal cause is the outworking of the Jewish genius to achieve the power of control. Here in the United States is the fact of this remarkable minority attaining in fifty years a degree of control that would be impossible to a ten times larger group of any other race... The finances of the world are in the control of Jews; their decisions and devices are themselves our economic laws."

Ford's biographer, William C. Richards, has argued in The Last Billionaire (1948): "He (Henry Ford) caused to have published a series of articles in which he set up the major postulate that there was a Jewish plot to rule the world by control of the machinery of commerce and exchange - by a super-capitalism based wholly on the fiction that gold was wealth." Professor Norman Cohn, the author of Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy (1966) has pointed out: "There is no real doubt that Ford knew perfectly well what he was sponsoring. He founded the Dearborn Independent in 1919 as a vehicle for his own 'philosophy' and he took a keen and constant interest in it; much of the contents consisted simply of edited versions of his talk."

By 1923 the Dearborn Independent was a notorious, mass-circulated, anti-Semitic propaganda sheet with a circulation of 500,000. Articles that appeared in the newspaper was published in book form. Entitled The International Jew, it was distributed widely and translated into sixteen different languages. The German edition, printed in Leipzig, was especially popular. Baldur von Schirach, who was later to become the head of the Hitler Youth claimed that he developed anti-Semite views at seventeen after reading the book by Ford. He later recalled: "We saw in Henry Ford the representative of success, also the exponent of a progressive social policy. In the poverty-stricken and wretched Germany of the time, youth looked toward America, and apart from the great benefactor, Herbert Hoover, it was Henry Ford who to us represented America."

Keith Sward, the author of The Legend of Henry Ford (1948) quotes a Jewish attorney who went on a world tour in the mid-1920s, said he saw copies of Ford's book in the "most remote corners of the earth". He maintained that "but for the authority of the Ford name, they would have never seen the light of day and would have never seen the light of day and would have been quite harmless if they had. With the magic name they spread like wildfire and became the Bible of every anti-Semite."

Adolf Hitler was another one who read The International Jew. He also Ford's autobiography, My Life and Work (1922). In 1923 Hitler heard that Ford was considering running for President. He told the Chicago Tribune, "I wish that I could send some of my shock troops to Chicago and other big American cities to help in the elections... We look to Heinrich Ford as the leader of the growing Fascist movement in America... We have just had his anti-Jewish articles translated and published. The book is being circulated to millions throughout Germany." The New York Times reported that there was a large picture of Henry Ford on the wall beside Hitler's desk in the Brown House.

After the failed Beer Hall Putsch Hitler was imprisoned at Landsberg Castle in Munich. At his trial in 1924, Erhard Auer, testified that Ford was giving money to the Nazi Party. Hitler's business manager, Max Amnan, proposed that Hitler should spend his time in prison writing his autobiography. Hitler, who had never fully mastered writing, was at first not keen on the idea. However, he agreed when it was suggested that he should dictate his thoughts to a ghostwriter. The prison authorities surprisingly agreed that Hitler's chauffeur, Emil Maurice, could live in the prison to carry out this task.

Hitler praises Henry Ford in Mein Kampf. "It is Jews who govern the Stock Exchange forces of the American union. Every year makes them more and more the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions; only a single great man, Ford, to their fury, still maintains full independence." James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979) has pointed out: Not only did Hitler specifically praise Henry Ford in Mein Kampf, but many of Hitler's ideas were also a direct reflection of Ford's racist philosophy. There is a great similarity between The International Jew and Hitler's Mein Kampf, and some passages are so identical that it has been said Hitler copies directly from Ford's publication. Hitler also read Ford's autobiography, My Life and Work, which was published in 1922 and was a best seller in Germany, as well as Ford's book entitled Today and Tomorrow. There can be no doubt as to the influence of Henry Ford's ideas on Hitler."

Dietrich Eckart, who spent time with Hitler at Landsberg Castle specifically mentioned that The International Jew was a source of inspiration for the Nazi leader. Both Hitler and Ford believed in the existence of a Jewish conspiracy - that the Jews had a plan to destroy the Gentile world and then take it over through the power of an international super-government. This sort of plan had been described in detail in The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, that had been published in Russia in 1903.

It is believed that the man behind the forgery was Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky, the head of the Paris section of Okhrana. It is argued he commissioned his agent, Matvei Golovinski, to produce the forgery. The plan was to present reformers in Russia, as part of a powerful global Jewish conspiracy and fomented anti-Semitism to deflect public attention from Russia's growing social problems. This was reinforced when several leaders of the 1905 Russian Revolution, such as Leon Trotsky, were Jews. Norman Cohn, the author of Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy (1966) has argued that the book played an important role in persuading fascists to seek the massacre of the Jewish people.

Despite evidence against the genuineness of the document, Hitler and Ford continued to defend its authenticity. Ford commented: "The only statement I care to make about the Protocols is that they fit in with what is going on... They have fitted the world situation up to this time. They fit it now." Ford also sponsored the printing of 500,000 copies of The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion in the United States.

Hitler told Herman Rauschning that he was "appalled" when he first read the Protocols: "The stealthiness of the enemy and his ubiquity! I saw at once we must copy it - in our own way of course." He admitted that the Protocols had convinced him the fight against the Jews was "the critical battle for the fate of the world!" Rauschning commented: "Don't you think you are attributing rather too much importance to the Jews? Hitler responded angrily: "No, No, No! It is impossible to exaggerate the formidable quality of the Jew as an enemy." Rauschning then took another approach: "But the Protocols are a manifest forgery... It couldn't possibly be genuine." Hitler replied that he did not care if it was "historically true" as its "intrinsic truth" was more important: "We must beat the Jew with his own weapon. I saw that the moment I had read the book."

Both Ford and Hitler believed that Jewish capitalists and Jewish communists were partners aiming to gain control over the nations of the world. Ford placed more emphasis on Jewish financiers and bankers, because as an industrialist he naturally came into close contact with them. Hitler, on the other hand, was more concerned with Jews who were members of the Social Democrat Party (SDP) and the German Communist Party (KPD) as they were a powerful opposition force in Germany in the 1920s.

Ford was especially worried by the Russian Revolution. If the ideas of Karl Marx established itself in America he would obviously be one of the first to suffer. In his book, My Life and Work (1922), he wrote: "We learned from Russia that it is the minority and not the majority who determine destructive action... There is in this country a sinister element that desires to creep in between the men who work with their hands and the men who think and plan... The same influence that drove the brains, experience, and ability out of Russia is busily engaged in raising prejudice here. We must not suffer the stranger, the destroyer, the hater of happy humanity to divide our people. In unity is America's strength - and freedom."

According to Norman Cohn, the author of Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy (1966) Ford deplored "the lack of moral standards" in modern commerce and blamed this on the Jews. Ford told one reporter: "When there's wrong in a country you'll find Jews... The Jew is a huckster who doesn't want to produce but to make something of what somebody else produces." In the Dearborn Independent Ford wrote: "A Jew has no attachment for the things he makes, for he doesn't make any; he deals in the things which other men make and regards them solely on the side of their money-making value."

.

According to James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979): "In the minds of Ford and Hitler, Communism was a completely Jewish creation. Not only was its founder, Karl Marx, the grandson of a rabbi, but more importantly Jews held leading positions, as well as a high percentage of the membership, in the Communist parties throughout the world. The International Jew stated that since the time of the French Revolution Jews had been involved in numerous movements to overthrow ruling regimes." In Mein Kampf Hitler pointed out: "In Russian bolshevism we must see Jewry's twentieth-century effort to take world domination unto itself."

Both Hitler and Ford contended that 75% of the Communists in Russia were Jews. This is not supported by the facts. At the time of the Russian Revolution there were only seven million Jews among the total Russian population of 136 million. Although police statistics showed the ratio of Jews participating in the revolutionary movement to the total Jewish population was six times that of the other nationalities in Russia, they were no way near the figures suggested by Hitler and Ford. Lenin admitted that "Jews provided a particularly high percentage of leaders of the revolutionary movement". He explained this by arguing "to their credit that today Jews provide a relatively high percentage of representatives of internationalism compared with other nations."

Of the 350 delegates at the Social Democratic Party in London in 1903, 25 out of 55 delegates were Jews. Of the 350 delegates in the 1907 congress, nearly a third were Jews. However, an important point which the anti-Semites overlooked is that of the Jewish delegates supported the Mensheviks, whereas only 10% supported the Bolsheviks, who led the revolution in 1917. According to a party census carried out in 1922, Jews made up 7.1% of members who had joined before the revolution. Jewish leaders of the revolutionary period, Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov and Genrikh Yagoda were all purged by Joseph Stalin in the 1930s.

Hitler and Ford also believed that the Jews had been responsible for Germany losing the First World War. The German historian, Joachim Riecker, believes that the core of Hitler's hatred was based on the belief that the Jews were responsible for Germany's defeat. Ford said in The International Jew that "the Jews were not German patriots during the war". They lost the war because "a) the spirit of Bolshevism which masqueraded under the name of German Socialism, b) Jewish ownership and control of the Press, c) Jewish control of the food supply and the industrial machinery of the country."

Charles Higham has argued: "Henry Ford was a knotty puritan, dedicated to the simple ideals of early-to-bed, early-to-rise, plain food, and no adultery. He didn't drink and fought a lifetime against the demon tobacco. He admired Hitler from the beginning, when the future Führer was a struggling and obscure fanatic. He shared with Hitler a fanatical hatred of Jews... Visitors to Hitler's headquarters at the Brown House in Munich noticed a large photograph of Henry Ford hanging in his office... Stacked high on the table outside were copies of Ford's book."

Ford was highly critical of the democratic system in the United States. According to Ford, democracy is nothing but a "levelling down of ability" Ford wrote in the Dearborn Independent that there could be "no greater absurdity and no greater disservice to humanity in general than to insist that all men are equal." Ford went on to argue that the Jews had used democracy to raise themselves up in society. He quotes the The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion as claiming the Jews stated: "We were the first to shout the words, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, among the people. These words have been repeated many times since by unconscious poll-parrots, flocking from all sides to this bait with which they have been ruined.... The presumably clever Gentiles did not understand the symbolism of the uttered words. Did not notice that in nature there is no equality."

Ford believed the motion picture industry "is exclusively under the control, moral and financial, of the Jewish manipulators of the public mind." According to Ford the Jews used the movies and the theatre to poison the American people with sensuality, indecency, appalling illiteracy, and endless liberal platitudes. Ford, like Hitler, did not like popular music. "Monkey talk, jungle squeals, grunts and squeaks camouflaged by a few feverish notes". It was not really "popular" but rather an artificial popularity was created for it by high-pressured advertising. Ford argued that the Jews had created the popularity of the African style to destroy the moral fabric of the white race.

Representatives of almost all national Jewish organizations and religious bodies issued a common declaration denouncing the Ford campaign. One hundred and nineteen prominent Christians, including Woodrow Wilson, called upon Ford to stop his "vicious propaganda". President Warren Harding privately asked Ford to halt the attacks. William Fox, president of Fox Film Corporation, threatened to show footage of Model T accidents in his newsreels, if Ford persisted in attacking the character of Jewish film executives and their motion pictures.

Soon most Jewish firms and individual Jews boycotted Ford products and Gentile firms who did business with Jewish concerns and were dependent on their good will followed suit to please their best customers. Although sales of Ford cars continued to grow. For example, in 1925, the company was producing 10,000 cars every 24 hours. This was 60 per cent of America's total output of cars. However, Henry Ford's campaign against the Jews, hurt the company in the eastern metropolitan centres. Senior executives later admitted that during the run of the anti-Semitic articles the company lost business which was never regained.

A prominent American Jew, Isaac Landman, challenged Ford to prove that a Jewish plot existed. Landman said he would guarantee to provide sufficient money to hire the world's leading detectives and would agree to print their findings, whatever they might be, in at least one hundred leading newspapers. Ford accepted the challenge but insisted on employing his own detectives. He established headquarters in New York City and hired a group of agents to "unmask the operation of the Secret World Government". His team included former senior members of the U.S. Secret Service.

Ford believed that Bernard Baruch, one of America's richest men, was one of the main leaders of this conspiracy. He and other prominent Jews were investigated. So also was Justice Louis Brandeis, a Jewish member of the Supreme Court (One of the justices, James McReynolds, hostility towards Jews was so strong he always refused to sit next to Brandeis during meetings.) Woodrow Wilson and Colonel Edward House were also investigated as they were considered by Ford as "Gentile fronts" for the "Secret World Government". Despite spending a great deal of money on the operation, Ford was unable to prove that a Jewish plot existed.

In 1927, Aaron Sapiro, a prominent Chicago attorney, accused Ford with libel for saying that he was involved in a plot with other Jewish middlemen to gain control of American agriculture. The case was settled out of court when Ford published a personal apology to Sapiro and a formal retraction of his attacks against the Jews. Ford asked for the forgiveness of the Jewish people and made a humble apology for the injustices done to them through his publications. He also announced that he was closing Dearborn Independent down. The reason for this change of heart was that Ford was told that the Jewish boycott of his cars was having a serious impact on sales. Ford was told that his proposed launch of the new Model A car would end in failure unless he ended his campaign against the Jews.

.

Despite closing down the Dearborn Independent, Ford did not change his mind about the Jews. He told Gerald L. Smith, one of the fascist leaders in the United States, that he hoped to republish The International Jew in the near future. The anti-Nazi journalist, Konrad Heiden, claimed that "Henry Ford, the famous automobile manufacturer gave money to the National Socialists directly or indirectly has never been disputed." Upton Sinclair, the American investigative journalist, discovered that the Nazi Party got $40,000 to reprint anti-Jewish pamphlets in German translations. The United States Ambassador to Germany, William E. Dodd, said in an interview that American industrialists such as Ford "had a great deal to do with bringing fascist regimes into being in both Germany and Italy."

The American journalist, Norman Hapgood, carried out an investigation into Henry Ford. He discovered that Ford was sending money to the Nazis via Boris Brasol. In one of his articles, Hapgood quotes the former head of the Russian constitutional government at Omsk as saying "I have seen the documentary proof that Boris Brasol has received money from Henry Ford." Brasol had worked for the United States secret service and after the First World War had worked closely with Ford in promoting The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.

Adolf Hitler and Henry Ford

Winifred Wagner, a close associate of Adolf Hitler, was sent by Kurt Ludecke, to gain funds for the Nazi Party. She admitted to James Pool in 1977: "Ford told me that he had helped to finance Hitler with money from the sales of automobiles and trucks that he had sent to Germany." Winifred suggested that Hitler was now more in need for money than ever. Ford replied that he was still willing to support if he was still working to free Germany from the Jews. Wagner arranged for Ludecke to pay Ford a visit.

At the arranged meeting, Ludecke promised that as soon as Hitler came to power, one of his first acts would be to inaugurate the social and political program which had been advocated in the Dearborn Independent. Ludecke explained that money was the only obstacle that stood between the Nazis and the fulfillment in Germany of Ford and Hitler's mutual views. In his memoirs published in 1938 Ludecke did not say how much Ford gave to Hitler. Ludecke hinted at why he could not tell the truth without hurting Ford. The Jewish boycott had "pinched him in the ledgers where even a multimillionaire is vulnerable." Lüdecke described Ford as having "clear, bright eyes and his strong face, almost free from wrinkles, did not betray his more than sixty years." It is claimed by CH that every year Ford sent Hitler a birthday present of 50,000 Reichsmarks.

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Henry Ford's The International Jew became a stock item of Nazi Germany propaganda. It has been claimed that "every school child in Germany came into contact with it many times during his education." The manager of the Ford Company in Germany in the mid-1930s, Edmund C. Heine, explained that the book had the backing of the German government and was an important factor in educating the nation "to understand the Jewish problem as it should be understood."

Carl Krauch claimed that he arranged for the Ford Company to retain its independence during Hitler's rule in the 1930s: "I myself knew Henry Ford and admired him. I went to see Goring personally about that. I told Goring that I myself knew his son Edsel, too, and I told Goring that if we took the Ford independence away from them in Germany, it would aggrieve friendly relations with American industry in the future. I counted on a lot of success for the adaptation of American methods in Germany's industries, but that could be done only in friendly cooperation. Goring listened to me and then he said: 'I agree. I shall see to it that the German Ford Company will not be incorporated in the Hermann Goring Company.' So I participated regularly in the supervisory board meetings to inform myself about the business processes of Henry Ford and, if possible, to take a stand for the Henry Ford Works after the war had begun. Thus, we succeeded in keeping the Ford Works working and operating independently of our government's seizure."

In the 1930s Ford opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. He was especially opposed to the National Labor Relations Act which established the rights of workers to join trade unions and to bargain collectively with their employers through representatives of their own choosing. Workers were now protected from their employers and as a result union membership grew rapidly. Ford refused to recognize the United Auto Workers and used armed police to deal with industrial unrest. Ford told a journalist from Collier's Weekly that left-wing unions "are organized by Jewish financiers, not labor". He added that "a union is a neat thing for a Jew to have on hand when he comes around to get his clutches on an industry."

from Hitler's representatives, Karl Kapp (left), and Fritz Hailer (right).

.

In 1938 Adolf Hitler awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle. Ford was the first American and only the fourth person in the world to receive this medal. Benito Mussolini, another of Hitler's financiers, had been granted the same award earlier that year. Harold L. Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, denounced Ford and other Americans "who obsequiously have accepted tokens of contemptuous distinction at a time when the bestower of them counts that day lost when he can commit no new crime against humanity." Ford was also criticized by the Jewish entertainer, Eddie Cantor, who called Ford "a damn fool for permitting the world's greatest gangster to give him a citation." Cantor then added "the more men like Ford we have, the more we must organize and fight."

Ford employed Harry Bennett, a former boxer, to head the Internal Security Department. Bennett employed various intimidation tactics to squash union organizing. The most famous incident, on 26th May, 1937, involved Bennett's security men beating with clubs UAW representatives, including Walter Reuther. While this was going on police chief Carl Brooks "did not give orders to intervene." The conflict became known as The Battle of the Overpass. Ford held out until signing an agreement with UAW in June 1941.

According to Charles Higham, the author of Trading with the Enemy (1983), Ford was more willing to help Nazi Germany than the British during the early stages of the Second World War: "Edsel and his father, following their meetings with Gerhardt Westrick at Dearborn in 1940, refused to build aircraft engines for England and instead built supplies of the 5-ton military trucks that were the backbone of German army transportation. They arranged to ship tires to Germany despite the shortages; 30 percent of the shipments went to Nazi-controlled territories abroad."

In 1940 Ford built a new automobile factory at Poissy in the German Occupied Zone. The plant began making airplane engines for the German government. It also built trucks for the German Army. Ford arranged for Nazi war criminal, Carl Krauch and Maurice Dollfus, to run the factory. It made a profit of 50 million francs in the first year of trading. When the plant was bombed by the Royal Air Force, Dollfus arranged for the German government to pay for compensation for the damage done.

On 16th February 1941, Henry Ford delivered a bitter attack on the Jews to The Manchester Guardian saying that the United States should make Britain and Germany fight until they both collapsed. To show his commitment to the America First Committee, Ford employed Charles Lindbergh as a member of his executive staff. This caused great controversy when on 17th December, 1941, ten days after Pearl Harbour, Lindbergh made a speech where he argued: "There is only one danger in the world-that is the yellow danger. China and Japan are really bound together against the white race. There could only have been one efficient weapon against this alliance.... Germany.... the ideal setup would have been to have had Germany take over Poland and Russia, in collaboration with the British, as a bloc against the yellow people and Bolshevism. But instead, the British and the fools in Washington had to interfere. The British envied the Germans and wanted to rule the world forever. Britain is the real cause of all the trouble in the world today."

The Ford plant at Willow Run produced over 8,000 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers during the war. However, he continued to supply the German Army with trucks and armored from its plant in Poissy and Oran in Algeria. In April 1943, Henry Morgenthau and Lauchlin Currie conducted a lengthy investigation into the Ford subsidiaries in French territory. The report concluded that "their production is solely for the benefit of Germany and the countries under its occupation" and the Germans have "shown clearly their wish to protect the Ford interests". Despite the report nothing was done about the matter.

Henry Ford died on 7th April, 1947.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Ford, Forum Magazine (October, 1928)

It has been asserted that machine production kills the creative ability of the craftsman. This is not true. The machine demands that man be its master; it compels mastery more than the old methods did. The number of skilled craftsmen in proportion to the working population has greatly increased under the conditions brought about by the machine. They get better wages and more leisure in which to exercise their creative faculties.

There are two ways of making money - one at the expense of others, the other by service to others. The first method does not "make" money, does not create anything; it only "gets" money - and does not always succeed in that. In the last analysis, the so-called gainer loses. The second way pays twice - to maker and user, to seller and buyer. It receives by creating, and receives only a just share, because no one is entitled to all. Nature and humanity supply too many necessary partners for that. True riches make wealthier the country as a whole.

Most people will spend more time and energy in going around problems than in trying to solve them. A problem is a challenge to your intelligence. Problems are only problems until they are solved, and the solution confers a reward upon the solver. Instead of avoiding problems, we should welcome them and through right thinking make them pay us profits. The discerning youth will spend his time learning direct methods, learning how to make his brain and hand work in harmony with each other so that the problem in hand may be solved in the simplest, most direct way that he knows.

(2) Henry Ford, The International Jew (1925)

The Jew is a race that has no civilization to point to no aspiring religion... no great achievements in any realm... We meet the Jew everywhere where there is no power. And that is where the Jew so habitually... gravitate to the highest places? Who puts him there? What does he do there? In any country, where the Jewish question has come to the forefront as a vital issue, you will discover that the principal cause is the outworking of the Jewish genius to achieve the power of control. Here in the United States is the fact of this remarkable minority attaining in fifty years a degree of control that would be impossible to a ten times larger group of any other race... The finances of the world are in the control of Jews; their decisions and devices are themselves our economic laws.

(3) James Pool, Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979)

Not only did Hitler specifically praise Henry Ford in Mein Kampf, but many of Hitler's ideas were also a direct reflection of Ford's racist philosophy. There is a great similarity between The International Jew and Hitler's Mein Kampf, and some passages are so identical that it has been said Hitler copies directly from Ford's publication. Hitler also read Ford's autobiography, My Life and Work, which was published in 1922 and was a best seller in Germany, as well as Ford's book entitled Today and Tomorrow. There can be no doubt as to the influence of Henry Ford's ideas on Hitler.

(4) Charles Higham, Trading with the Enemy (1983)

Edsel Ford had a great deal to do with the European companies. He was different in character from his father. He was a nervous, high-strung man who tried to work off his extreme tensions and guilts over inherited wealth in a furious addiction to tennis and other sports. Darkly handsome, with a whipcord physique, he was miserable at heart. He could not relate to his father, who despised him, and his inner distress caused him severe stomach ulcers that developed into gastric cancer by the early 1940s. Nevertheless, he and his father had one thing in common. True figures of The Fraternity, they believed in "Business as Usual" in time of war.

Edsel was on the board of American LG. and General Aniline and Film throughout the 1930s. He and his father, following their meetings with Gerhardt Westrick at Dearborn in 1940, refused to build aircraft engines for England and instead built supplies of the 5-ton military trucks that were the backbone of German army transportation. They arranged to ship tires to Germany despite the shortages; 30 percent of the shipments went to Nazi-controlled territories abroad. German Ford employee publications included such editorial statements as, "At the beginning of this year we vowed to give our best and utmost for final victory, in unshakable faithfulness to our Fuehrer." Invariably, Ford remembered Hitler's birthday and sent him 50,000 Reichsmarks a year. His Ford chief in Germany was responsible for selling military documents to Hitler. Westrick's partner Dr. Albert continued to work in Hitler's cause when that chief came to the United States to continue his espionage.

(5) Carl Krauch, testimony when interrogated by the American authorities (1946)

I myself knew Henry Ford and admired him. I went to see Goring personally about that. I told Goring that I myself knew his son Edsel, too, and I told Goring that if we took the Ford independence away from them in Germany, it would aggrieve friendly relations with American industry in the future. I counted on a lot of success for the adaptation of American methods in Germany's industries, but that could be done only in friendly cooperation. Goring listened to me and then he said: 'I agree. I shall see to it that the German Ford Company will not be incorporated in the Hermann Goring Company.' So I participated regularly in the supervisory board meetings to inform myself about the business processes of Henry Ford and, if possible, to take a stand for the Henry Ford Works after the war had begun. Thus, we succeeded in keeping the Ford Works working and operating independently of our government's seizure.