Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City on 3rd February, 1894. According to his biographer, Karal Ann Marling: "The young Norman was skinny and clumsy at sports. He feared the rough neighbourhoods near his family's home on the Upper West Side. Coddled by his mother, Nancy, who boasted of her English heritage and artistic forbears, he also came to resent her imaginary illnesses and spates of religious fervor."

Norman's father, Waring Rockwell, worked in the textile industry. He was also an amateur artist and spent time with his son copying illustrations out of magazines. Waring also read to his family the novels of Charles Dickens. While he read, Norman drew the characters from the novels. According to one art critic: "His (Norman Rockwell) strong sense of narrative and his eye for the telling detail were byproducts of those long, nurturing evenings in his father's company." During this period his artistic heroes were Charles Dana Gibson, Harrison Fisher, Howard Pyle and Newell Convers Wyeth.

In 1907 the family moved to Mamaroneck, a small settlement on the Long Island Sound. Rockwell went to the local school but travelled the 25 miles to Manhatten to study at the the New York School of Art, an institution run by the artist, William Merritt Chase. In 1909, at the age of 15, he left high school and enrolled in the National Academy School.

Rockwell found the teaching at the academy very conventional and in 1910 he joined the Art Students League. With teachers such as Thomas Eakins, Robert Henri, John Sloan, Art Young, George Luks, Boardman Robinson, George Bellows, Howard Pyle and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, it developed a reputation for progressive teaching methods and radical politics. At this time it had nearly a thousand students and was considered the most important art school in the country.

His main teacher was Thomas Fogarty. He later claimed that Fogarty's main contribution to his career was that he taught him the importance of meeting deadlines and following his client's wishes. Fogarty was impressed with Rockwell's talent that in 1913 he arranged for him to be appointed art editor of Boys' Life, the journal of the Boy Scouts of America.

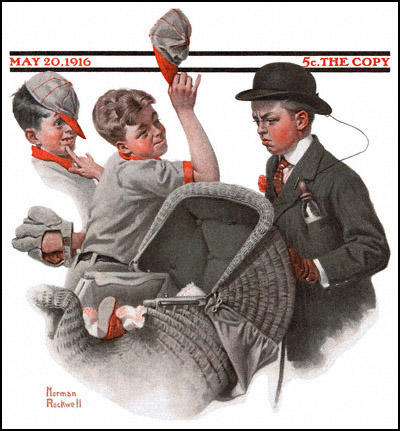

Rockwell really wanted to work for the Saturday Evening Post and in March 1916 he visited its main office in Philadelphia. He showed the editor, George Horace Lorimer, a collection of front cover ideas. Lorimer was so impressed with the work that he purchased two cover pictures and commissioned three more. This was the start of his long-term relationship with the magazine that was to last over 45 years.

The author of Norman Rockwell (2005) has argued: "The pictorial cover was crucial to the success of a magazine. It had to make itself visible and comprehensible at a distance, so the casual passerby would want to pluck that issue off the rack at the newsstand. It had to identify the Saturday Evening Post and carry with it some slight hint of the character of the journal... In a sense, it also needed to mirror the taste and status of the potential reader, who could see him - or herself in that image. Covers were a tricky business, and one crucial to the success of the Saturday Evening Post."

Rockwell's first Saturday Evening Post cover appeared on 20th May, 1916. Boy with Baby Carriage shows a little boy, dressed in his Sunday best, pushing a baby in a pram past two other boys in baseball uniforms who mock him for the "unmanly" task he is performing. At this time, the covers were only printed in two colours, and Rockwell makes good use of the red and back on the white paper.

Rockwell used one boy, Billy Paine, to pose for all three characters. Rockwell used hats, haircuts, and facial expressions to disguise this fact. Rockwell later recalled: "At the beginning of the modeling sessions I'd set a stack of nickels on a table beside my easel. Every 25 minutes... I'd transfer of the nickels to the other side of the table, saying, Now that's your pile."

Later that year, Rockwell married Irene O'Connor, a local schoolteacher. The couple moved to New Rochelle where he takes over a studio that was formerly owned by Frederick Remington. By this time he was in great demand as an illustrator and provided a large number of covers for Saturday Evening Post and The Literary Digest. Rockwell was also recruited to produce illustrations for advertising that appeared in magazines and on posters.

Soon after the United States entered the First World War, Rockwell joined the US Navy. Over the next year Rockwell worked for US Navy publications. After the Armistice Rockwell returned to full-time illustrating. As well as magazine work, Rockwell became involved in designing advertising campaigns. As Karal Ann Marling has pointed out: "The big money of the era was in advertising art. Foodstuffs had been one of the first customer products to be branded... In the 1920s, a new, modern wave of edibles hit the mass market, with a corresponding demand for artwork to sell chewing gum, soft drinks, and candy."

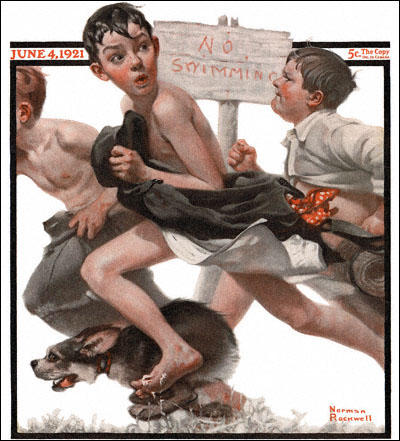

One of Rockwell's most popular paintings, No Swimming, appeared on the front cover of the Saturday Evening Post on 4th June, 1921. The art critic, Christopher Finch, has argued: "We find that it has been painted in an almost impressionistic way. There is no question hem of an outline having been drawn then filled in with color. On the contrary, the image is built up from areas of boldly applied pigment - a well-loaded brush is evident - overlapping and overlaying each other to build up planes that create the illusion of solidity and depth. (Note in particular the way in which the anatomy of the boy in the foreground has been evoked.) Many of the edges of forms have been deliberately blurred in this picture, partly to help produce a sense of speed, but largely as a natural consequence of this approach to image-making. Even Rockwell's highly stylized signature is loosely painted."

In 1930 Rockwell went to Hollywood to paint the film-star Gary Cooper for the Saturday Evening Post. This was used to advertise Cooper's latest film, The Texan. As the author of Norman Rockwell (2005) has pointed out: "His time in Hollywood had important artistic consequences: Rockwell was becoming a master of theatrical and cinematic effects. His covers and occasional illustrations took on the appearance of moments from the movies, when the actors face the camera directly, when directors compose their scenes to under-score key moments in the script, when overstated costuming allows the audience to identify the genre at a glance. Rockwell's trip to Hollywood in 1930 cemented the connection between his art and the art of the filmmaker."

Rockwell divorced Irene in 1930. Soon afterwards he met Mary Barstow, another young school-teacher and later that year they got married. Over the next few years she gave birth to three sons: Jerry (1932), Tommy (1933) and Peter (1936).

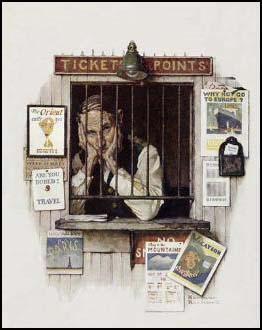

Rockwell was a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. However, he was unable to express his political views in his covers for the Saturday Evening Post. He therefore had to rely on subtle methods to get his views across. For example, his cover, The Ticket Seller, that appeared on 24th April, 1937, shows a man selling tickets to holiday destinations, while trapped like a circus lion within his own cage.

In 1939 Rockwell and his family moved to Arlington, Vermont. On the outbreak of the Second World War, Rockwell offered his services free of charge to the United States Office of War Information (OWI) in Washington. He was rejected by the person in charge of pictorial propaganda with the words: "The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we're going to use fine arts men, real artists."

Rockwell refused to be beaten and began thinking about he could help. He was eventually inspired by a joint statement made by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill about the reasons why it was important to fight a war against Nazi Germany. In his autobiography, he points out that after returning from a town meeting: "My gosh, I thought, that's it. There it is. Freedom of Speech. I'll illustrate the Four Freedoms using my Vermont neighbors as models. I'll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes. Freedom of Speech - a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want - a Thanksgiving dinner."

The Freedom of Speech painting showed Jim Edgerton, who had argued for the building of a new high school in Arlington. Edgerton had found no support for his views. But the meeting had listened respectfully to his views. Norman Rockwell considered this was a good example of freedom of speech in action.

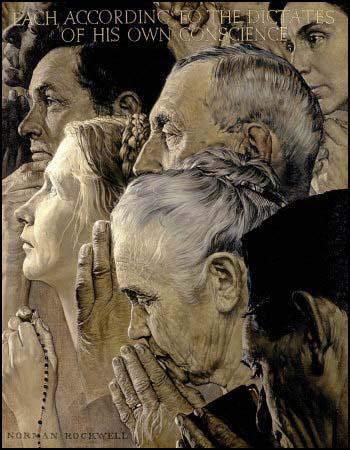

Rockwell found coming up with an idea for a painting on religion much more difficult. After making several false starts he painted a close-up portrait of seven individuals of various skin tones, united in prayer. Freedom to Worship included the words in golden letters at the top of the canvas: "Each according to the dictates of his own conscience."

Freedom from Want depicted his own family. The Rockwell cook, Mrs. Wheaton, is shown presenting the turkey. His wife, Mary Rockwell, can be seen on the left side of the table. His mother is the elderly lady seated across from her. Rockwell later recalled: "She (Mrs. Wheaton) cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it. That was one of the few times I've ever eaten the model."

The final painting, Freedom from Fear, was produced during the Blitz. It shows the husband and wife watching their two children asleep. The man carries a newspaper, with a headline referring to the bombing of London. His biographer, Karal Ann Marling, argues that: "The rag doll abandoned on the floor just behind his feet echoes the posture of the sleeping children but, in her limp, discarded form, also alludes to the European children who did not enjoy the safety of a warm bed guarded by caring parents."

When the editor of the Saturday Evening Post saw these four paintings he decided to publish them inside the magazine so that they would be suitable for framing. These were so popular that the United States Office of War Information printed 2,500,000 posters of the paintings. The original paintings went out on tour.

Another popular cover produced during the Second World War was Rosie the Riveter (29th May, 1943). The term Rosie the Riveter had been first used in a song of the same name written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb in 1942. The song portrays Rosie as an assembly line worker, who is filling the role of man who had joined the armed forces. By the time Rockwell painted the picture Rosie had become a feminist icon.

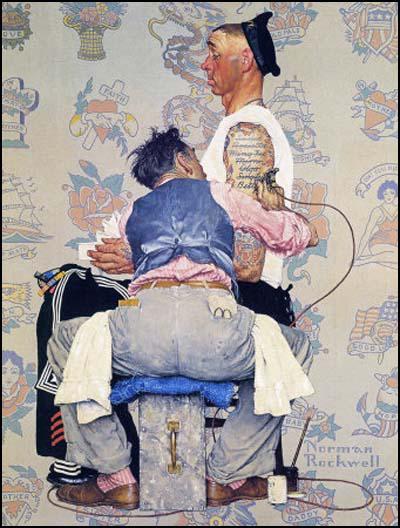

Rockwell also produced humorous covers for the Saturday Evening Post during the war. A good example of this is Tattoo Artist that appeared on 4th March, 1944. In the painting the tattoos is in the process of crossing out the names of girls already displayed on the arm of the sailor. The work makes fun of sailors who had the reputation of having a different girlfriend at every port.

The art critic, Ken Johnson, has argued: "It is no secret that Rockwell relied on photographs to achieve the seeming naturalism of his paintings. But the extent and sophistication of his use of photography from the late 1930s on will come as a surprise to many of his fans and detractors. Rockwell did not shoot his pictures, but employed professional photographers, including Gene Pelham, Bill Scovill, Louis J. Lamone and others who remain unidentified. But Rockwell did orchestrate every other aspect of studio sessions. He found and bought props; recruited friends, acquaintances and relatives as models; constructed sets; and conceived scenes like a Hollywood movie director."

After the war Rockwell was probably the best known artist in the United States. Christopher Finch has pointed out: "We should not judge Rockwell by individual work, nor even by a selection of his finest pictures, but rather by the cumulative effect of his total output. It is this that makes Rockwell so outstanding a figure in the pantheon of American popular culture. Elsewhere I have remarked that it seems, at first glance, almost absurd to talk of Norman Rockwell as having a distinctive style - his stock in trade is quasi-photographic realism, and his technique derives from a variety of conventional academic sources - yet a Rockwell painting is immediately recognizable as a Rockwell painting. Clearly he does have a style that is unlike any other. It is not easy to define. however, because it dots not depend upon any broad mannerisms. It is, rather, made up of small but significant deviations from the photographic and academic norms."

In 1947 Rockwell helped to establish the Famous Artists School in Westport, Connecticut. The organisation, headed by Albert Dorne, ran corresponding courses. Faculty members that included Rockwell, Austin Briggs, Stevan Dohanos, Robert Fawcett, Peter Helck, Fred Ludekens, Al Parker, Ben Stahl, Harold von Schmidt and Jon Whitcomb, produced step-by-step textbooks on how to produce art work for magazine covers and illustrations for advertising campaigns.

Rockwell's wife, Mary, suffered from alcoholism and a variety of other health problems. She was treated at the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In 1953 Norman Rockwell moved to the town to be close to his wife and to receive treatment for depression. In 1959 Mary died unexpectedly of heart failure.

Rockwell also had strong political views. He felt particularly strongly over the issue of civil rights. Ken Stuart, the art director of the Saturday Evening Post, began turning down his front covers. On other occasions, he had section of a cover painting repainted without telling the artist that he had done so. Rockwell threatened to stop working for the magazine, but the editor, Ben Hibbs, promised it would not happen again.

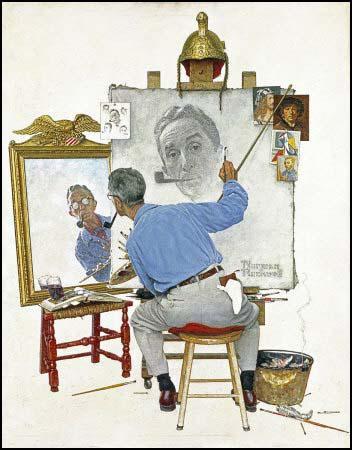

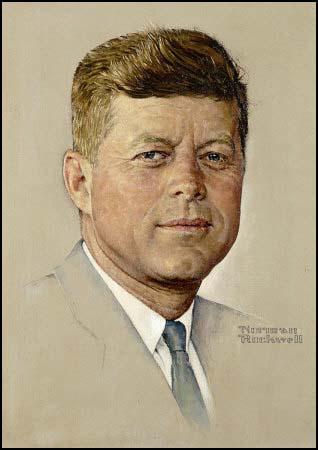

On 13th February, 1960, the magazine's front-cover was Triple Self-Portrait. The Saturday Evening Post acknowledged his importance to the magazine by publishing a serial version of autobiography that year. This was later released as a book, My Adventures as an Illustrator. Rockwell was a great supporter of John F. Kennedy and his last illustration for the magazine was a portrait of the assassinated president on 14th December, 1963.

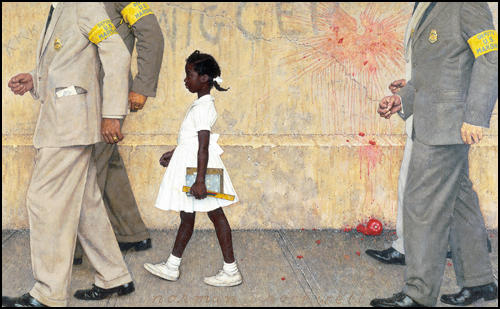

The death of Kennedy convinced him to join Look Magazine, as a commentator of current affairs. Rockwell's first double-page illustration for the magazine, The Problem We All Live With (14th January, 1964) was one of his most memorable paintings. It shows Ruby Bridges, who in 1960, when she was 6 years old, became involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaign to integrate the New Orleans School system. When she entered William Frantz Elementary School in 1960 she became the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.

Rockwell also painted Southern Justice, that dealt with the deaths of three Congress on Racial Equality field-workers in Meridian, Mississippi, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, on 21st June, 1964. The painting appeared in Look Magazine on 29th June, 1965. The magazine also published several of his paintings that reflected his opposition to the Vietnam War.

Karal Ann Marling has argued: "Some Americans turned a blind eye to Rockwell's pleas for racial justice and idealism, however. In the summer of 1964, three so-called Freedom Riders James Chancy, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were killed for their efforts to register black voters in the South. Eventually, their bodies were discovered in an earthen dam in rural Philadelphia, Mississippi. Rockwell responded in Look in June of 1965 with an imaginative recreation of their martyrdom. In the harsh glare of headlights, the shadows of armed Klansmen draw closer to the bleeding figure of Chancy, in the arms of one of his white companions. The painting argues for the brotherhood of the trio and presents their attackers as inhuman creatures of the night. The landscape is an almost Biblical scene of desolation: bare, rock-strewn, and forbidding -a killing ground. It is Norman Rockwell's most passionate indictment to date of the nation whose little missteps and personal follies had been his lifelong preoccupation. The second great issue of the decade was the spreading conflict in Indochina. By the end of 1965, 150,000 American troops were fighting in Vietnam and opposition to the war was growing. In a work originally painted for the Congress of Racial Equality, Rockwell shows slaughter as the great equalizer of America's blacks and whites. The two young men who lie side by side in death have become Blood Brothers. In at least one of the preliminary sketches for the work, they wear the uniforms of U. S. Marines."

Norman Rockwell died at his home in Stockbridge on 8th November, 1978.

Primary Sources

(1) Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell (1979)

We should not judge Rockwell by individual work, nor even by a selection of his finest pictures, but rather by the cumulative effect of his total output. It is this that makes Rockwell so outstanding a figure in the pantheon of American popular culture.

Elsewhere I have remarked that it seems, at first glance, almost absurd to talk of Norman Rockwell as having a distinctive style - his stock in trade is quasi-photographic realism, and his technique derives from a variety of conventional academic sources - yet a Rockwell painting is immediately recognizable as a Rockwell painting. Clearly he does have a style that is unlike any other. It is not easy to define. however, because it dots not depend upon any broad mannerisms. It is, rather, made up of small but significant deviations from the photographic and academic norms.

One thing that we will discover if we study Rockwell's work carefully is chat the best of his early works are, in general, more "painterly" than most of his later canvases, though these later canvases tended to make more successful covers. When I speak of certain early works as being "painterly." I mean that they are conceived and executed more as conventional easel paintings, whereas the later works often have the look of tinted drawings (even though they are executed in oil paint on canvas). This difference should not be taken as a hard and fast rule, but it does represent a significant tendency, as a few examples will show.

If we turn to the 1921 cover No Swimming, we find that it has been painted in an almost impressionistic way. There is no question hem of an outline having been drawn then filled in with color. On the contrary, the image is built up from areas of boldly applied pigment - a well-loaded brush is evident - overlapping and overlaying each other to build up planes that create the illusion of solidity and depth. (Note in particular the way in which the anatomy of the boy in the foreground has been evoked.) Many of the edges of forms have been deliberately blurred in this picture, partly to help produce a sense of speed, but largely as a natural consequence of this approach to image-making. Even Rockwell's highly stylized signature is loosely painted.

(2) Karal Ann Marling, Norman Rockwell (2005)

By 1942, when the poster was designed, Norman had been painting Post covers for 26 years. Every year, the pressure was greater. Would a particular cover sell magazines? Was there another young artist, a better one, waiting in the wings to dethrone him? The Post ran through several editors in rapid succession after Lorimer's retirement: each one had fresh expectations and demands. Would the magazine fold entirely? Was his stuff as good today as it was 26 years ago? And then there were the advertising agencies dangling long-term contracts which would leave Rockwell in a perpetual dither over deadlines on pictures designed to sell canned vegetables and Coca-Cola.

These problems, in addition to the anxieties bred by war, made Norman Rockwell reevaluate his talent and his career. Could he paint a "Big Picture", a real painting, noncommercial, with an important and universal meaning? The immediate inspiration for this shift in focus was the Atlantic Charter, promulgated by President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in August of 1941. The Charter would become the keystone of' the American war effort, a declaration of the principles upon which a just world order in the postwar future would rest. The sentiments expressed were noble but to Rockwell's mind, a little too noble to be understood readily by the average American.

(3) Deborah Solomon, New York Times (1st July, 2010)

Rockwell’s paintings are easy to recognize. In the years surrounding World War II his covers for The Saturday Evening Post depicted America as a small-town utopia where people are consistently decent and possess great reserves of fellow-feeling. Doctors spend time with patients whether or not they have health insurance. Students cherish their teachers and remember their birthdays. Citizens at town hall meetings stand up and speak their mind without getting booed or shouted down by gun-toting rageaholics.

This is America before the fall, or at least before searing divisions in our government and general population shattered any semblance of national solidarity. Rockwell’s scenes of the small and the local speak to us in the age of the global because they offer a fantasy of civic togetherness that today seems increasingly remote. “To me the most important part of Rockwell’s work is that it illustrates compassion and caring about other people,” the filmmaker George Lucas, who lives in Marin County, Calif., said recently. “You could almost say he was a Buddhist painter.”

Steven Spielberg, speaking from Los Angeles, had similar praise. “Anything for Norman,” he said, when asked to discuss his work. “He was always on my mind because I had a great deal of respect for how he could tell stories in a single frozen image. Entire stories.”

(4) Karal Ann Marling, Norman Rockwell (2005)

Norman Rockwell is America's best loved artist... America's best-loved artist was an illustrator who, in a career that spanned some 60 years of the last century, almost never painted a picture that wasn't intended to be an ad, a cover, a calendar, a a gloss on a magazine story, or a Christmas card. Indeed, the for-profit context in which Norman Rockwell laboured so successfully may make him the most American of all artists in a period that both witnessed and celebrated the primacy of American commercial enterprise. By the mid-1930s, Rockwell was the most famous illustrator in America, a figure whose success prolonged the life of the "Golden Age" of commercial picture-making well into the 20th century. The economic Depression of the period hardly touched Rockwell; its effects were curiously absent from his work, for the most part, too, as if Norman consciously aimed to distract and reassure his vast following.

(5) Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell (1979)

Often, in his later work Rockwell uses a rather artificial kind of texture to give the illusion of painterlinetis to what is. In fact, a tinted drawing. In particular, he is fond of a very deliberate kind of impasto (physical buildup of pigment, often applying it in what seems at first glance like a wholly inappropriate way, as for example in his treatment of the mirror in Triple Self Portrait. An extreme example of the application o( this technique occurs in the 1946 cover "Commuters," This is a composition governed almost entirely by carefully drawn outlines, but practically the entire area of the canvas has been further enlivened through the use of thickly textured underpaintirg - roofs. platforms, hillside are all given variations of texture - and clearly this was no accident. Rockwell used this device because he knew that it reproduced well.

(6) Karal Ann Marling, Norman Rockwell (2005)

Her story was well known in 1964. Robert Coles had written a study of her drawings, showing the effects of segregation on African-American youngsters. John Steinbcck, in his best-selling Travels with Charlie, reported the cruel and hateful epithets that greeted Ruby Bridges every day, as her federal guards escorted tier to school through hostile crowds. By making Ruby small and her guardians large, Rockwell increased the drama of her plight; her white clothes define her as an innocent confronting the evil of American racial prejudice. The Problem We All Live With disclosed a "new," 70-year-old Norman Rockwell, an activist who used the most appealing qualities of his former work to crusade for social justice.

Rockwell's idealism was echoed by that of John P. Kennedy and the stirring challenge to the nation offered by Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign. During 1964, many of the problems and ideals addressed by the young president had already been tackled. The Civil Rights Act was signed into law.... Rockwell reconstructed the Democratic party convention of 1960 in a Look illustration entitled A Tone for Greatness. That phrase came from a Kennedy campaign slogan visible on the placards carried by the delegates in the painting. This time, instead of staging an event and taking a picture of it, Norman worked from press photographs of the event, as a documentarist or history painter, using his art to challenge his audience to rekindle the spirit of the recent past.

Some Americans turned a blind eye to Rockwell's pleas for racial justice and idealism, however. In the summer of 1964, three so-called Freedom Riders James Chancy, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman were killed for their efforts to register black voters in the South. Eventually, their bodies were discovered in an earthen dam in rural Philadelphia, Mississippi. Rockwell responded in Look in June of 1965 with an imaginative recreation of their martyrdom. In the harsh glare of headlights, the shadows of armed Klansmen draw closer to the bleeding figure of Chancy, in the arms of one of his white companions. The painting argues for the brotherhood of the trio and presents their attackers as inhuman creatures of the night. The landscape is an almost Biblical scene of desolation: bare, rock-strewn, and forbidding -a killing ground. It is Norman Rockwell's most passionate indictment to date of the nation whose little missteps and personal follies had been his lifelong preoccupation.

The second great issue of the decade was the spreading conflict in Indochina. By the end of 1965, 150,000 American troops were fighting in Vietnam and opposition to the war was growing. In a work originally painted for the Congress of Racial Equality, Rockwell shows slaughter as the great equalizer of America's blacks and whites. The two young men who lie side by side in death have become Blood Brothers. In at least one of the preliminary sketches for the work, they wear the uniforms of U. S. Marines.

(7) Ken Johnson, New York Times (9th December, 2010)

If you think you know all you need to know about Norman Rockwell, think again. “Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera” at the Brooklyn Museum is a revelation. It is no secret that Rockwell relied on photographs to achieve the seeming naturalism of his paintings. But the extent and sophistication of his use of photography from the late 1930s on will come as a surprise to many of his fans and detractors.

Rockwell did not shoot his pictures, but employed professional photographers, including Gene Pelham, Bill Scovill, Louis J. Lamone and others who remain unidentified. But Rockwell did orchestrate every other aspect of studio sessions. He found and bought props; recruited friends, acquaintances and relatives as models; constructed sets; and conceived scenes like a Hollywood movie director. He might have missed his calling. He could have been another Frank Capra, director of the inspirational sob-fest “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum and Ron Schick, a guest curator, this exhibition presents more than 100 black-and-white photographs, most of which have never been seen in public before. Along with the prints, which are the product of a recent two-year project to digitize almost 20,000 negatives from the Rockwell archives, are magazine covers and magazine and book pages with reproductions of Rockwell’s illustrations.

There are 17 paintings and 10 drawings included, which is more than enough to show what was gained and what was lost in the translation. While the paintings have a sensuous physicality that photographs lack, many of the photographs have a chilly psychological subtlety that is muffled in the paintings.

(8) Christopher Finch, Norman Rockwell (1979)

Occasionally Rockwell indulged in caricature, but more usually, when dealing with the face, he gave us a kind of heightened naturalism that verged on caricature without quite crossing the line. He was particularly good at dealing with such things as family relationships as they are expressed in shared features. He had the knack of concentrating on those little physical similarities that we are all aware of but cannot always define precisely. If we look again at the father and son in Breaking Home Ties, we can see exactly what Rockwell was capable of when faced with such similerities. The hands, too. In that painting are worth careful study. They arc as expressive of family bonds as anything that Rockwell has found in the two faces. Always, then, it is the little human touches that make Rockwell's paintings memorable. Without them, his brilliance as a storyteller could never have had quite the same ring of authenticity.

(9) Jonathan Jones, The Guardian (19th February, 2002)

Rockwell's idyllic Thanksgiving is one of four paintings he made in 1943 to illustrate America's Four Freedoms, to spur his countrymen on in the second world war. They were published in the Saturday Evening Post and the canvases went on a national tour, during which they were seen by over a million people and were credited with selling $132m worth of war bonds. Rockwell's Four Freedoms have lived in the national imagination ever since. Freedom from Want - the Thanksgiving scene - is the most famous, perhaps because Rockwell rightly anticipated that the future of America would be one of galloping prosperity. The others are Freedom of Speech, in which a blue-collar guy gets up to speak at a town meeting and is heard with respect; Freedom to Worship, depicting people of different faiths praying together; and Freedom from Fear, with a couple tucking their children up in bed, the man holding a paper with news of bombing raids in Europe, knowing that here in America no air raid siren will split the night. Rockwell later said he didn't feel quite happy with Freedom from Fear - it was, he said, "based on a rather smug idea" that Americans were safe from external attack.

Rockwell would have loved being recognised as a serious artist. But he might have been uncomfortable with any suggestion that he was an unquestioning flag-waver, cheering George Bush to the next stage in the war against terrorism. He was not blind to America's flaws, even though his art might dream of the way things should be. In the 1960s he was shocked by the violence of the South towards civil rights campaigners. His picture Southern Justice records the murder of activists in Mississippi. It's very different from the cute image of a white boy served by a black waiter on a train that he had painted in 1946. Rockwell claimed that when he worked for the Post its editor "told me never to show coloured people except as servants".

After he parted company with the magazine in 1963, Rockwell became more openly political, and the politics were not what people might have expected; indeed one of the many American artists who chronicled the breakup of Norman Rockwell's idyllic mid-century America was Norman Rockwell. Rockwell's 1960s pictures are images of tension and conflict. The Problem We All Live With (1963) has a little girl walking to a newly desegregated school with an escort of four US marshals. It adopts her scale, dwarfed by the huge legs of the marshals. On the wall behind is vile racist graffiti and the blood-red remains of a thrown tomato. Rockwell was accused by angry letter writers of "vicious lying propaganda... for the crime of racial integration".