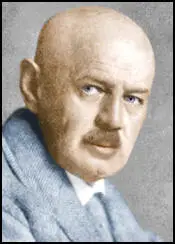

Dietrich Eckart

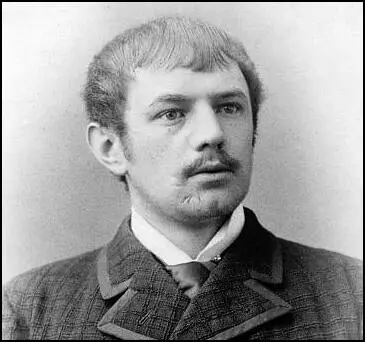

Dietrich Eckart was born in Neumarkt, Germany, on 23rd March, 1868. His mother Anna Eckart, died when he was young and he had a difficult childhood being expelled from several schools. His father, Christian Eckart, a successful lawyer, also died and left him a sizeable amount of money.

Eckart studied medicine but left before he obtained his degree. For the next few years he attempted to make a living from writing plays and poems. After spending his family inheritance he found work as a journalist. Eckart developed right wing views and associated with members of the Thule Society.

Konrad Heiden, was a journalist working in Munich who investigated the life of Eckart: "Born of well-to-do parents in a little town of northern Bavaria, he had been a failure as a law student because he had drunk too much and worked too little. Then in Berlin - already in his forties - he had led the life of a vagrant who believes himself to be a poet.... He had grown to be a morphine addict and had spent some time in an asylum for the mentally diseased, where his theatrical gifts finally found a haven, for he had staged plays there and used the inmates as actors."

Eckart opposed the German Revolution in 1918 which he regarded as Jewish-inspired. He also edited the anti semitic periodical Auf gut Deutsch. During this period he became friends with Alfred Rosenberg. In January 1919 he joined with Hermann Esser, Gottfried Feder and Karl Harrer, to form the German Workers Party (GPW). Harrer was elected as chairman of the party. Eckart pointed out: "We need a fellow at the head who can stand the sound of a machine gun. The rabble need to get fear into their pants. We can't use an officer, because the people don't respect them any more. The best would be a worker who knows how to talk... He doesn't need much brains.... He must be a bachelor, then we'll get the women."

On 30th May, 1919, Captain Karl Mayr, was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents and informants. On 12th September, Mayr sent Adolf Hitler to attend a meeting of the German Workers Party (GWP). Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever."

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist.

Anton Drexler had mixed feelings about Hitler but was impressed with his abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Adolf Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Major Karl Mayr, to join. Hitler also discovered that Ernst Röhm, was also a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP. Drexler wrote to a friend: "An absurd little man has become member No. 7 of our Party."

In February 1920, the German Workers Party published its first programme which became known as the "Twenty-Five Points". It was written by Eckart, Adolf Hitler, Gottfried Feder and Anton Drexler. In the programme the party refused to accept the terms of the Versailles Treaty and called for the reunification of all German people. To reinforce their ideas on nationalism, equal rights were only to be given to German citizens. "Foreigners" and "aliens" would be denied these rights. To appeal to the working class and socialists, the programme included several measures that would redistribute income and war profits, profit-sharing in large industries, nationalization of trusts, increases in old-age pensions and free education. Feder greatly influenced the anti-capitalist aspect of the Nazi programme and insisted on phrases such as the need to "break the interest slavery of international capitalism" and the claim that Germany had become the "slave of the international stock market".

Hitler had more respect for Eckart than other leaders of the GWP. The journalist, Konrad Heiden, pointed out: "The recognized spiritual leader of this small group was Eckart, the journalist and poet, twenty-one years older than Hitler. He had a strong influence on the younger man, probably the strongest anyone ever has had on him. And rightly so. A gifted writer, satirist, orator, even (or so Hitler believed) thinker, Eckart was the same sort of uprooted, agitated, and far from immaculate soul.... He could tell Hitler that he (like Hitler himself) had lodged in flop-houses and slept on park benches because of Jewish machinations which (in his case) had prevented him from becoming a successful playwright." Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) agrees: "He (Eckart) talked well even when he was fuddled with beer, and had a big influence on the younger and still very raw Hitler. He lent him books, corrected his style of expression in speaking and writing, and took him around with him."

Eckart decided that the GWP needed its own newspaper. Major Ernst Röhm agreed and together they persuaded his commanding officer, Major General Franz Ritter von Epp to purchase the Völkischer Beobachter (Racial Observer) from the Thule Society for 60,000 marks. The money came from wealthy friends and secret army funds. Eckart became the editor of the paper and used it to publicize the policies of the GWP. Later, Ernst Hanfstaengel provided $1,000 to ensure the daily publication of the newspaper. As William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964), has pointed out: "It became a daily, thus giving Hitler the prerequisite of all German political parties, a daily newspaper in which to preach the party's gospels."

Hitler's reputation as an orator grew and it soon became clear that he was the main reason why people were joining the party. At one meeting in Hofbräuhaus he attracted an audience of over 2,000 people and several hundred new members were enrolled. This gave Hitler tremendous power within the organization as they knew they could not afford to lose him. One change suggested by Hitler concerned adding "Socialist" to the name of the party. Hitler had always been hostile to socialist ideas, especially those that involved racial or sexual equality. However, socialism was a popular political philosophy in Germany after the First World War. This was reflected in the growth in the German Social Democrat Party (SDP), the largest political party in Germany. Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end.

Adolf Hitler advocated that the party should change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. In April 1920, the German Workers Party became the NSDAP. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman.

Konrad Heiden, a journalist working in Munich, observed the way Hitler gained control of the party: "Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them - wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement."

Eckart's biographer, Louis L. Snyder, has argued: "By 1923 Eckart's connections in Munich, added to Hitler's oratorical gifts, gave strength and prestige to the fledgling Nazi political movement. Eckart accompanied Hitler at rallies and was at his side in party parades. While Hitler stirred the masses, Eckart wrote panegyrics to his friend. The two were inseparable. Hitler never forgot his early sponsor... Hitler, he said, was his North Star... He spoke emotionally of his fatherly friend, and there were often tears in his eyes when he mentioned Eckart's name."

Dietrich Eckart died of a heart-attack on 26th December, 1923.

Primary Sources

(1) Morgan Philips Price, Germany in Transition (1923)

The rump of the old parties is now working in close touch with a new party, the so-called National Socialist Party under Herr Hitler and Herr Eckert, who is organizing under a Fascist banner those elements of the trade unions who are tired of the cowardice of the Social-Democratic leaders. These new groups under the leadership of Hitler and Ludendorff have come out openly for a Fascist dictatorship, and by tactics of provocation of the Socialists and Republican elements in the rest of Germany, and by attacks on Socialist meetings and demonstrations, hope to ferment civil war, leading up to the seizure of power by their armed forces. During the winter of 1922-23, Hitler's storm battalions organized raiding expeditions to the industrial towns of North Bavaria. His plan of campaign is to seize power in North Bavaria, or Frankenland, and use it as a base of operations against Thuringen and Saxony where Social-Democratic governments are in power with the aid of Communist votes. From there the way would be open to the industrial districts of Prussia in the North. Success will very much depend on the goodwill of the German heavy industry trusts who, after the murder of Rathenau, withdrew their financial support from most of these Fascist bodies. But after the French occupation of the Ruhr, the heavy industries began again to support the Bavarian Fascists.

(2) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

Dietrich Eckart had introduced Alfred Rosenberg, the young fugitive from Russia, to the party. But for the time being the recognized spiritual leader of this small group was Eckart, the journalist and poet, twenty-one years older than Hitler. He had a strong influence on the younger man, probably the strongest anyone ever has had on him. And rightly so. A gifted writer, satirist, orator, even (or so Hitler believed) thinker, Eckart was the same sort of uprooted, agitated, and far from immaculate soul. Born of well-to-do parents in a little town of northern Bavaria, he had been a failure as a law student because he had drunk too much and worked too little. Then in Berlin - already in his forties - he had led the life of a vagrant who believes himself to be a poet. He could tell Hitler that he (like Hitler himself) had lodged in flop-houses and slept on park benches because of Jewish machinations which (in his case) had prevented him from becoming a successful playwright. He had grown to be a morphine addict and had spent some time in an asylum for the mentally diseased, where his theatrical gifts finally found a haven, for he had staged plays there and used the inmates as actors. Now he was the grand old - and often drunk - man of the young Nazi Movement.

(3) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962)

Dietrich Eckart was considerably older than Hitler, well known as a journalist, poet, and playwright, a Bavarian character, fond of beer, food, and talk... Eckart was a friend of Rohm, with violent nationalist, anti-democratic, and anti-clerical opinions, a racist with an enthusiasm for Nordic folk-lore and a taste for Jew-baiting. At the end of the war he owned a scurrilous sheet called Auf gut Deutsch and became the editor of the Volkischer Beobachter, for which be found the greater part of the purchase price. Eckart was a man who had read widely - he had translated Peer Gynt and had a passion for Schopenhauer. He talked well even when he was fuddled with beer, and had a big influence on the younger and still very raw Hitler. He lent him books, corrected his style of expression in speaking and writing, and took him around with him.