German Workers Party

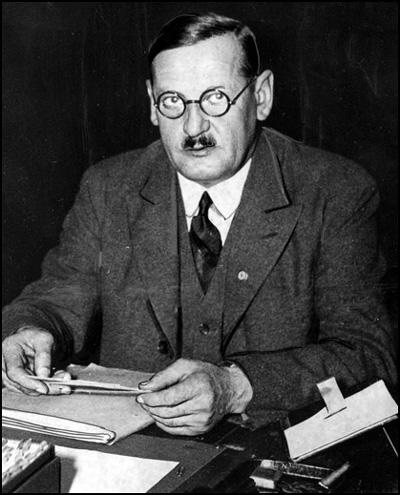

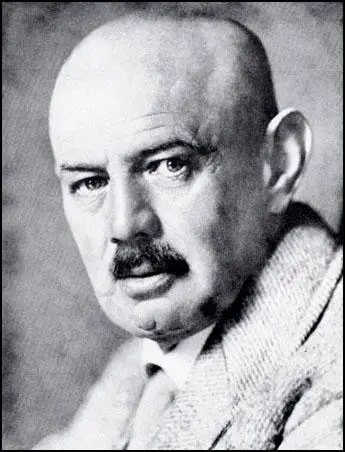

Anton Drexler, a Munich locksmith, was a a member of the Fatherland Front but believed it to be hopelessly out of touch with the mood of the masses, and that these were coming increasingly under the influence of anti-national and anti-militarist propaganda. On 7th March 1918, Drexler set up a Committee of Independent Workmen. Drexler's idea was to form an organisation that would "combat the Marxism of the free trade unions" and to agitate for a "just" peace for Germany. His long-term objective was to create a party which would be both working class and nationalist. (1)

After six months it only had 40 members and in January 1919 decided to join with right-wing journalist, Karl Harrer, to form the German Workers Party (GPW). Other early members included Hermann Esser, Gottfried Feder and Dietrich Eckart. Harrer was elected as chairman of the party. Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "Its total membership was little more than Drexler's original forty (Committee of Independent Workmen), activity was limited to discussions in Munich beer-halls, and the committee of six had no clear idea of anything more ambitious." (2)

On 30th May, 1919, Captain Karl Mayr, was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents and informants. On 12th September, Mayr sent Adolf Hitler to attend a meeting of the German Workers Party (GWP). Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever." (3)

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist. (4)

Hitler commented: "In his (Feder's) little book he described how his mind had thrown off the shackles of the Marxist and trades-union phraseology, and that he had come back to the nationalist ideals. The pamphlet secured my attention the moment I began to read, and I read it with interest to the end. The process here described was similar to that which I had experienced in my own case ten years previously. Unconsciously my own experiences began to stir again in my mind. During that day my thoughts returned several times to what I had read; but I finally decided to give the matter no further attention." (5)

Louis L. Snyder has argued that Feder's views appealed to Hitler for political reasons: "For Hitler, Feder's separation between stock exchange capital and the national economy offered the possibility of going into battle against the internationalization of the German economy without threatening the founding of an independent national economy by a fight against capital. Best of all, from Hitler's point of view, was the fact that he could identify international capitalism as wholly Jewish-controlled. Hitler became a member of the German Workers' Party and Feder became his friend and guide." (6)

Anton Drexler had mixed feelings about Hitler but was impressed with his abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Adolf Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Major Karl Mayr, to join. Hitler also discovered that Ernst Röhm, was also a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP. Drexler wrote to a friend: "An absurd little man has become member No. 7 of our Party." (7)

Louis L. Snyder has argued that Drexler's political ideas were very important in developing his own philosophy: "Hitler was impressed with Drexler's ideas. He agreed wholeheartedly with the concept that there existed a diabolical Jewish-capitalistic-Masonic conspiracy which had to be counteracted. He believed that Drexler was right: on the one side there were the innocent German worker, farmer, and soldier; on the other there was the common enemy... the capitalistic Jews. From this germ came the essence of Hitler's Nazism." (8)

Hitler gave his early impression of Anton Drexler and Karl Harrer in Mein Kampf (1925): "Herr Drexler... was a simple worker, as speaker not very gifted, moreover no soldier. He had not served in the Army, and was not a soldier during the war, because his whole being was weak and uncertain, he was not a soldier during the war, and because his whole being was weak and uncertain, he was not a real leader for us. He (and Herr Harrer) were not cut out to be fanatical enough to carry the movement in their hearts, nor did he have the ability to use brutal means to overcome the opposition to a new idea inside the party. What was needed was one fleet as a greyhound, smooth as leather, and hard as Krupp steel." (9)

The German Worker's Party used some of this money from Karl Mayr and Ernst Röhm to advertise their meetings. Hitler was often the main speaker and it was during this period that he developed the techniques that made him into such a persuasive orator. Hitler always arrived late which helped to develop tension and a sense of expectation. He took the stage, stood to attention and waited until there was complete silence before he started his speech. For the first few months Hitler appeared nervous and spoke haltingly. Slowly he would begin to relax and his style of delivery would change. He would start to rock from side to side and begin to gesticulate with his hands. His voice would get louder and become more passionate. Sweat poured of him, his face turned white, his eyes bulged and his voice cracked with emotion. He ranted and raved about the injustices done to Germany and played on his audience's emotions of hatred and envy. By the end of the speech the audience would be in a state of near hysteria and were willing to do whatever Hitler suggested. As soon as his speech finished Hitler would quickly leave the stage and disappear from view. Refusing to be photographed, Hitler's aim was to create an air of mystery about himself, hoping that it would encourage others to come and hear the man who was now being described as "the new Messiah". (10)

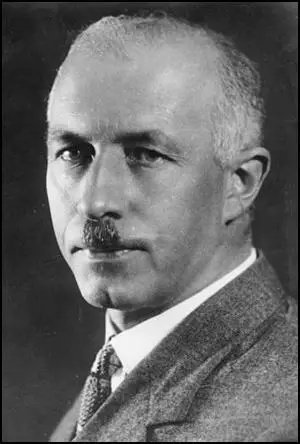

Hitler had more respect for Dietrich Eckart than other leaders of the GWP. The journalist, Konrad Heiden, pointed out: "The recognized spiritual leader of this small group was Eckart, the journalist and poet, twenty-one years older than Hitler. He had a strong influence on the younger man, probably the strongest anyone ever has had on him. And rightly so. A gifted writer, satirist, orator, even (or so Hitler believed) thinker, Eckart was the same sort of uprooted, agitated, and far from immaculate soul.... He could tell Hitler that he (like Hitler himself) had lodged in flop-houses and slept on park benches because of Jewish machinations which (in his case) had prevented him from becoming a successful playwright." (11)

Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) agrees: "Dietrich Eckart was considerably older than Hitler, well known as a journalist, poet and playwright, a Bavarian character, fond of beer, food, and talk... He talked well even when he was fuddled with beer, and had a big influence on the younger and still very raw Hitler. He lent him books, corrected his style of expression in speaking and writing, and took him around with him." (12)

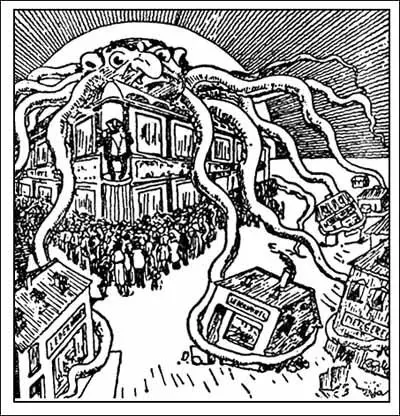

In February 1920, the German Worker's Party published its first programme which became known as the "Twenty-Five Points". It was written by Adolf Hitler, Gottfried Feder, Anton Drexler and Dietrich Eckart. In the programme the party refused to accept the terms of the Versailles Treaty and called for the reunification of all German people. To appeal to the working class and socialists, the programme included several measures that would redistribute income and war profits, profit-sharing in large industries, nationalization of trusts, increases in old-age pensions and free education. Feder greatly influenced the anti-capitalist aspect of the Nazi programme and insisted on phrases such as the need to "break the interest slavery of international capitalism" and the claim that Germany had become the "slave of the international stock market".

To reinforce their ideas on nationalism, equal rights were only to be given to German citizens. "Foreigners" and "aliens" would be denied these rights. "Only a member of the race can be a citizen. A member of the race can only be one who is of German blood, without consideration of creed. Consequently no Jew can be a member of the race. Whoever has no citizenship is to be able to live in Germany only as a guest, and must be under the authority of legislation for foreigners. The right to determine matters concerning administration and law belongs only to the citizen. Therefore we demand that every public office, of any sort whatsoever, whether in the Reich, the county or municipality, be filled only by citizens. We combat the corrupting parliamentary economy, office-holding only according to party inclinations without consideration of character or abilities." (13)

Department Store Octopus' eats up small German traders" (c. 1920)

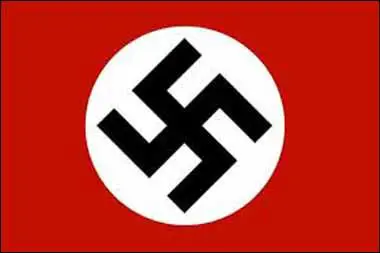

In 1920 Hitler designed a flag for the the German Worker's Party: "I myself, meanwhile, after innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag with a red background, a white disk, and a black swastika in the middle. After long trials I also found a definite proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the swastika.... At the sametime we immediately ordered the corresponding armlets for our squad of men who kept order at meetings. The new men who kept order at meetings. The new flag appeared in public in the midsummer of 1920. It suited our movement admirably, both being new and young. Not a soul had seen this flag before; its effect at the time was something akin to that of a blazing torch... The red expressed the social thought underlying the movement. White the national thought. And the swastika signified the mission allotted to us - the struggle for the victory of the Aryan mankind and at the sametime the triumph of the ideal of creative work which is itself and will always will be anti-Semitic." (14)

Hitler's reputation as an orator grew and it soon became clear that he was the main reason why people were joining the party. At one meeting in Hofbräuhaus he attracted an audience of over 2,000 people and several hundred new members were enrolled. This gave Hitler tremendous power within the organization as they knew they could not afford to lose him. One change suggested by Hitler concerned adding "Socialist" to the name of the party. Hitler had always been hostile to socialist ideas, especially those that involved racial or sexual equality. However, socialism was a popular political philosophy in Germany after the First World War. This was reflected in the growth in the German Social Democrat Party (SDP), the largest political party in Germany. (15)

Adolf Hitler advocated that the party should change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. In April 1920, the German Workers Party became the NSDAP. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman. (16)

Konrad Heiden, a journalist working in Munich, observed the way Hitler gained control of the party: "Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them - wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement." (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925)

When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever.

(2) Ian Kershaw Hitler 1889-1936 (1998)

Hitler's part in the early development of the German Workers' Party (subsequently the NSDAP) is obscured more than it is clarified by his own tendentious account in Mein Kampf. As usual, this is characterized less by pure invention than by selective memory and distortion of facts. And, as throughout his book, Hitler's version of events is aimed, more than all else, at elevating his own role as it denigrates, plays down, or simply ignores that of all others involved. It amounts, as always in Hitler's own account, to the story of a political genius going his way in the face of adversity, a heroic triumph of the will. The story was the core of the "party legend" which in later years Hitler never tired of retelling at inordinate length as the preface to his major speeches. It was that of the political genius who joined a tiny body with grandiose ideas but no hope of realizing them, raising it single-handedly to a force of the first magnitude which would come to rescue Germany from its plight.

Hitler wrote contemptuously of the organization he had joined. The state of the party was depressing in the extreme. The committee constituted practically the whole membership. Though it attacked parliamentary rule, its own matters were decided, after "interminable argument", by majority vote. It met in the dingy back rooms of Munich pubs. It had no permanent headquarters. In fact, it had no membership forms, no printed matter, not even a rubber stamp. Invitations to party meetings were handwritten or produced on a typewriter.

(3) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

Success and money finally won for Hitler complete domination over the National Socialist Party. He had grown too powerful for the founders; they - Anton Drexler among them-wanted to limit him and press him to the wall. But it turned out that they were too late. He had the newspaper behind him, the backers, and the growing S.A. At a certain distance he had the Reichswehr behind him too. To break all resistance for good, he left the party for three days, and the trembling members obediently chose him as the first, unlimited chairman, for practical purposes responsible to no one, in place of Anton Drexler, the modest founder, who had to content himself with the post of honorary chairman (July 29, 1921). From that day on, Hitler was the leader of Munich's National Socialist Movement.

(4) German Worker's Party: Twenty-Five Points (24th February, 1920)

1. We demand the unification of all Germans in the Greater Germany on the basis of the people's right to self-determination.

2. We demand equality of rights for the German people in respect to the other nations; abrogation of the peace treaties of Versailles and St. Germain.

3. We demand land and territory (colonies) for the sustenance of our people, and colonization for our surplus population.

4. Only a member of the race can be a citizen. A member of the race can only be one who is of German blood, without consideration of creed. Consequently no Jew can be a member of the race.

5. Whoever has no citizenship is to be able to live in Germany only as a guest, and must be under the authority of legislation for foreigners.

6. The right to determine matters concerning administration and law belongs only to the citizen. Therefore we demand that every public office, of any sort whatsoever, whether in the Reich, the county or municipality, be filled only by citizens. We combat the corrupting parliamentary economy, office-holding only according to party inclinations without consideration of character or abilities.

7. We demand that the state be charged first with providing the opportunity for a livelihood and way of life for the citizens. If it is impossible to sustain the total population of the State, then the members of foreign nations (non-citizens) are to be expelled from the Reich.

8. Any further immigration of non-citizens is to be prevented. We demand that all non-Germans, who have immigrated to Germany since 2 August 1914, be forced immediately to leave the Reich.

9. All citizens must have equal rights and obligations.

10. The first obligation of every citizen must be to work both spiritually and physically. The activity of individuals is not to counteract the interests of the universality, but must have its result within the framework of the whole for the benefit of all. Consequently we demand:

11. Abolition of unearned (work and labour) incomes. Breaking of debt (interest)-slavery.

12. In consideration of the monstrous sacrifice in property and blood that each war demands of the people, personal enrichment through a war must be designated as a crime against the people. Therefore we demand the total confiscation of all war profits.

13. We demand the nationalisation of all (previous) associated industries (trusts).

14. We demand a division of profits of all heavy industries.

15. We demand an expansion on a large scale of old age welfare.

16. We demand the creation of a healthy middle class and its conservation, immediate communalization of the great warehouses and their being leased at low cost to small firms, the utmost consideration of all small firms in contracts with the State, county or municipality.

17. We demand a land reform suitable to our needs, provision of a law for the free expropriation of land for the purposes of public utility, abolition of taxes on land and prevention of all speculation in land.

18. We demand struggle without consideration against those whose activity is injurious to the general interest. Common national criminals, usurers, profiteers and so forth are to be punished with death, without consideration of confession or race.

19. We demand substitution of a German common law in place of the Roman Law serving a materialistic world-order.

20. The state is to be responsible for a fundamental reconstruction of our whole national education program, to enable every capable and industrious German to obtain higher education and subsequently introduction into leading positions. The plans of instruction of all educational institutions are to conform with the experiences of practical life. The comprehension of the concept of the State must be striven for by the school [Staatsbürgerkunde] as early as the beginning of understanding. We demand the education at the expense of the State of outstanding intellectually gifted children of poor parents without consideration of position or profession.

21. The State is to care for the elevating national health by protecting the mother and child, by outlawing child-labor, by the encouragement of physical fitness, by means of the legal establishment of a gymnastic and sport obligation, by the utmost support of all organizations concerned with the physical instruction of the young.

22. We demand abolition of the mercenary troops and formation of a national army.

23. We demand legal opposition to known lies and their promulgation through the press. In order to enable the provision of a German press, we demand, that: a. All writers and employees of the newspapers appearing in the German language be members of the race; b. Non-German newspapers be required to have the express permission of the State to be published. They may not be printed in the German language; c. Non-Germans are forbidden by law any financial interest in German publications, or any influence on them, and as punishment for violations the closing of such a publication as well as the immediate expulsion from the Reich of the non-German concerned. Publications which are counter to the general good are to be forbidden. We demand legal prosecution of artistic and literary forms which exert a destructive influence on our national life, and the closure of organizations opposing the above made demands.

24. We demand freedom of religion for all religious denominations within the state so long as they do not endanger its existence or oppose the moral senses of the Germanic race. The Party as such advocates the standpoint of a positive Christianity without binding itself confessionally to any one denomination. It combats the Jewish-materialistic spirit within and around us, and is convinced that a lasting recovery of our nation can only succeed from within on the framework: The good of the state before the good of the individual.

25. For the execution of all of this we demand the formation of a strong central power in the Reich. Unlimited authority of the central parliament over the whole Reich and its organizations in general. The forming of state and profession chambers for the execution of the laws made by the Reich within the various states of the confederation. The leaders of the Party promise, if necessary by sacrificing their own lives, to support by the execution of the points set forth above without consideration.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 74

(2) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 64

(3) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925) page 124

(4) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 56

(5) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925) page 127

(6) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 90

(7) Robert Melvin Spector, World Without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust (2004) page 137

(8) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 90

(9) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925) page 202

(10) John Simkin, Hitler (1988) page 14

(11) Konrad Heiden, Hitler: A Biography (1936) page 85

(12) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) pages 78-79

(13) German Worker's Party: Twenty-Five Points (24th February, 1920)

(14) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925) page 276

(15) John Simkin, Hitler (1988) page 15

(16) Rudolf Olden, Hitler the Pawn (1936) page 91

(17) Konrad Heiden, Hitler: A Biography (1936) page 95