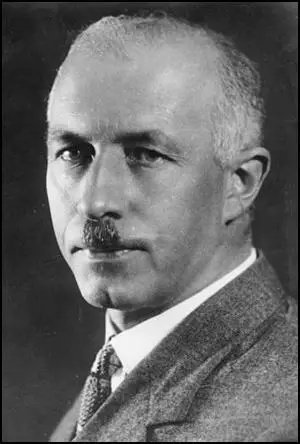

Gottfried Feder

Gottfried Feder, the son of a government official, was born in Würzburg, Germany, on 27th January, 1883. After attending schools in Ansbach and Munich, he studied engineering in Berlin and Zürich. In 1908 he started his own company constructing airplane hangers.

During the First World War Feder developed a hostility to Germany's wealthy bankers and in 1919 he published his Manifesto on Breaking the Shackles of Interest. According to Louis L. Snyder: "Feder became convinced that his country's economic ruin could be attracted to the manipulators of high finance. He favoured retaining the capitalist system, especially such productive assets as factories, mines, and machines, but he would abolish the idea of interest because it created no value."

On 30th May 1919 Captain Karl Mayr was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department in the German Army in Munich. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents or informants and to organize a series of educational courses to train selected officers and men in "correct" political and ideological thinking. Mayr recruited Feder to give lectures to soldiers at Munich University. Corporal Adolf Hitler was one of those who attended his lectures.

On 7th March 1918, Anton Drexler set up a Committee of Independent Workmen. Drexler's idea was to form an organisation that would "combat the Marxism of the free trade unions" and to agitate for a "just" peace for Germany. His long-term objective was to create a party which would be both working class and nationalist. After six months it only had 40 members and in January 1919 decided to join with right-wing journalist, Karl Harrer, to form the German Workers's Party (GPW). Other early members included Feder, Hermann Esser and Dietrich Eckart. Harrer was elected as chairman of the party.

On 30th May, 1919, Captain Karl Mayr, was appointed as head of the Education and Propaganda Department. He was given considerable funds to build up a team of agents and informants. On 12th September, Mayr sent Adolf Hitler to attend a meeting of the German Worker's Party (GWP). Hitler recorded in Mein Kampf (1925): "When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever."

Hitler discovered that the party's political ideas were similar to his own. He approved of Drexler's German nationalism and anti-Semitism but was unimpressed with what he saw at the meeting. Hitler was just about to leave when a man in the audience began to question the logic of Feder's speech on Bavaria. Hitler joined in the discussion and made a passionate attack on the man who he described as the "professor". Drexler was impressed with Hitler and gave him a booklet encouraging him to join the GWP. Entitled, My Political Awakening, it described his objective of building a political party which would be based on the needs of the working-class but which, unlike the Social Democratic Party (SDP) or the German Communist Party (KPD) would be strongly nationalist.

Hitler commented: "In his (Feder's) little book he described how his mind had thrown off the shackles of the Marxist and trades-union phraseology, and that he had come back to the nationalist ideals. The pamphlet secured my attention the moment I began to read, and I read it with interest to the end. The process here described was similar to that which I had experienced in my own case ten years previously. Unconsciously my own experiences began to stir again in my mind. During that day my thoughts returned several times to what I had read; but I finally decided to give the matter no further attention."

Louis L. Snyder has argued that Feder's views appealed to Hitler for political reasons: "For Hitler, Feder's separation between stock exchange capital and the national economy offered the possibility of going into battle against the internationalization of the German economy without threatening the founding of an independent national economy by a fight against capital. Best of all, from Hitler's point of view, was the fact that he could identify international capitalism as wholly Jewish-controlled. Hitler became a member of the German Workers' Party and Feder became his friend and guide."

Anton Drexler was impressed with Hitler's abilities as an orator and invited him to join the party. Hitler commented: "I didn't know whether to be angry or to laugh. I had no intention of joining a ready-made party, but wanted to found one of my own. What they asked of me was presumptuous and out of the question." However, Hitler was urged on by his commanding officer, Major Karl Mayr, to join. Hitler also discovered that Ernst Röhm, was also a member of the GWP. Röhm, like Mayr, had access to the army political fund and was able to transfer some of the money into the GWP.

In February 1920, the German Workers's Party published its first programme which became known as the "Twenty-Five Points". In the programme the party refused to accept the terms of the Versailles Treaty and called for the reunification of all German people. To reinforce their ideas on nationalism, equal rights were only to be given to German citizens. "Foreigners" and "aliens" would be denied these rights. To appeal to the working class and socialists, the programme included several measures that would redistribute income and war profits, profit-sharing in large industries, nationalization of trusts, increases in old-age pensions and free education. Feder greatly influenced the anti-capitalist aspect of the Nazi programme and insisted on phrases such as the need to "break the interest slavery of international capitalism" and the claim that Germany had become the "slave of the international stock market".

Hitler's reputation as an orator grew and it soon became clear that he was the main reason why people were joining the party. At one meeting in Hofbräuhaus he attracted an audience of over 2,000 people and several hundred new members were enrolled. This gave Hitler tremendous power within the organization as they knew they could not afford to lose him. One change suggested by Hitler concerned adding "Socialist" to the name of the party. Hitler had always been hostile to socialist ideas, especially those that involved racial or sexual equality. However, socialism was a popular political philosophy in Germany after the First World War. This was reflected in the growth in the German Social Democrat Party (SDP), the largest political party in Germany. Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end.

Adolf Hitler advocated that the party should change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Hitler, therefore redefined socialism by placing the word "National" before it. He claimed he was only in favour of equality for those who had "German blood". Jews and other "aliens" would lose their rights of citizenship, and immigration of non-Germans should be brought to an end. In April 1920, the German Workers Party became the NSDAP. Hitler became chairman of the new party and Karl Harrer was given the honorary title, Reich Chairman.

Throughout the 1920s Feder was a leader of the anti-capitalist wing of the Nazi Party. In 1924 he was elected to the Reichstag. He put forward his views in Das Programm der NSDAP (1931), Kampf gegen die Hochfinannz (1933) and Die Juden (1933) where he expressed his anti-semitic views.

As Feder held the important post of chairman of the party's economic council, his anti-capitalist views led to a decline in financial support from Germany's major industrialists. Hjalmar Schacht warned Hitler that Feder's economic planning apparatus would ruin the German economy. After pressure from figures such as Albert Voegler, Gustav Krupp, Friedrich Flick, Fritz Thyssen and Emile Kirdorf, Hitler decided to move the party away from Feder's left-wing economic theories.

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933 he appointed Feder as Under-Secretary at the Ministry of Economics. Feder was disappointed that he had not been given a more senior position. Konrad Heiden pointed out that Feder also had to serve under someone who completely opposed his economic policies: "The post of under-secretary was an humiliating position ... His new superior was almost a stranger to the party, but familiar to the stock exchange... he was Doctor Karl Schmitt, general director of the largest German insurance company. A more pronounced representative of rapacious capital would have been hard to find; Schmitt had spent his life lending money and collecting interest; he had literally bought his way into the National Socialist Movement by giving the party generous aid in hard times."

Feder continued to campaign for nationalization, profit-sharing, the abolition of unearned incomes and the "thraldom of interest". Hitler refused to do this. As Alan Bullock, the author of Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) has pointed out: "Hitler had never been a Socialist; he was indifferent to economic questions. What he saw, however, was that radical economic experiments at such a time would throw the German economy into a state of confusion, and would prejudice, if not destroy, the chances of cooperation with industry and business to end the Depression and bring down the unemployment figures."

Hitler confirmed this in a speech he made on 6th July, 1933: "The revolution is not a permanent state of affairs, and it must not be allowed to develop into such a state. The stream of revolution released must be guided into the safe channel of evolution.... We must therefore not dismiss a business man if he is a good business man, even if he is not yet a National Socialist; and especially not if the National Socialist who is to take his place knows nothing about business. In business, ability must be the only authoritative standard.... History will not judge us according to whether we have removed and imprisoned the largest number of economists, but according to whether we have succeeded in providing work.... The ideas of the programme do not oblige us to act like fools and upset everything, but to realize our trains of thought wisely and carefully. In the long run our political power will be all the more secure, the more we succeed in underpinning it economically."

Feder, as one of the leaders of the left-wing of the Nazi Party, Hitler saw him as a threat to his leadership. After the Night of the Long Knives where other left-wingers such as Gregor Strasser and Ernst Röhm were murdered, Feder resigned from the government telling his friends that Hitler had betrayed the Third Reich.

Gottfried Feder worked as a university lecturer until his death on 24th September, 1941.

Primary Sources

(1) Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (1925)

When I arrived that evening in the guest room of the former Sternecker Brau (Star Corner)... I found approximately 20–25 persons present, most of them belonging to the lower classes. The theme of Feder’s lecture was already familiar to me; for I had heard it in the lecture course... Therefore, I could concentrate my attention on studying the society itself. The impression it made upon me was neither good nor bad. I felt that here was just another one of these many new societies which were being formed at that time. In those days everybody felt called upon to found a new Party whenever he felt displeased with the course of events and had lost confidence in all the parties already existing. Thus it was that new associations sprouted up all round, to disappear just as quickly, without exercising any effect or making any noise whatsoever.

(2) Adolf Hitler, speech (6th July, 1933)

The revolution is not a permanent state of affairs, and it must not be allowed to develop into such a state. The stream of revolution released must be guided into the safe channel of evolution.... We must therefore not dismiss a business man if he is a good business man, even if he is not yet a National Socialist; and especially not if the National Socialist who is to take his place knows nothing about business. In business, ability must be the only authoritative standard.... History will not judge us according to whether we have removed and imprisoned the largest number of economists, but according to whether we have succeeded in providing work.... The ideas of the programme do not oblige us to act like fools and upset everything, but to realize our trains of thought wisely and carefully. In the long run our political power will be all the more secure, the more we succeed in underpinning it economically. The Reichsstatthalter, must therefore see to it that no organizations or Party offices assume the functions of government, dismiss individuals and make appointments to offices, to do which the Reich Government alone - and in regard to business the Reich Minister of Economics - is competent.