Ernest Jones

Ernest Jones, the son of Thomas Jones, a colliery manager and his wife, Mary Ann Lewis, was born in Gowerton, Wales, on 1st January 1879. He had two younger sisters, Elizabeth and Sybil. He was brought up in the Church of England and was educated at Swansea Grammar School and Llandovery College. (1)

In 1896 Jones began the first part of his medical studies at University College, which he continued in 1898 at University College Hospital. During this period he became committed to an evolutionary, materialistic, and atheistic world view. He initially attempted to establish himself as a neurologist, and was heavily influenced by the work of John Hughlings Jackson. (2)

In 1905 he set up a practice as a consultant physician in Harley Street, together with his best friend, the surgeon Wilfred Trotter. Soon afterwards he came across the work of Sigmund Freud. (3) He later wrote that from Freud's writings he formed "the deep impression of there being a man in Vienna who actually listened with attention to every word his patients said to him... a revolutionary difference from the attitude of previous physicians." It came as a revelation. "I was trying to do so myself, but I had never heard of anyone doing so.... Freud was a true psychologist." (4)

Jones attempted to combine his interest in Freud's ideas with his clinical work with children. However, in 1906 he was arrested and charged with two counts of indecent assault on two adolescent girls whom he had interviewed in his capacity as an inspector of schools for "mentally defective" children. At the court hearing Jones maintained his innocence, claiming the girls were fantasizing about any inappropriate actions by him. The magistrate refused to believe the testimony of such children and Jones was acquitted. (5)

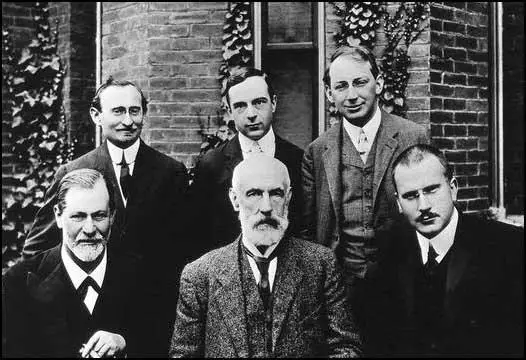

Ernest Jones and Sigmund Freud

Another complaint against Jones was made in 1908. At the time he was employed as a pathologist at the West End Hospital for Nervous Diseases. Jones claimed he accepted a colleague’s challenge to demonstrate the repressed sexual memory underlying the hysterical paralysis of a ten-year-old girl’s arm. However, he conducted the interview without informing the girl’s consultant and did not arrange for a chaperone. After complaints from the girl’s parents about discussing sexual topics without the presence of a third person he was forced to resign his hospital post. (6) In his autobiography, Free Associations: Memories of a Psycho-Analyst (1959), Ernest Jones wrote about these two incidents in some detail. He argued that the children in these incidents had projected their own sexual feelings upon him. (7)

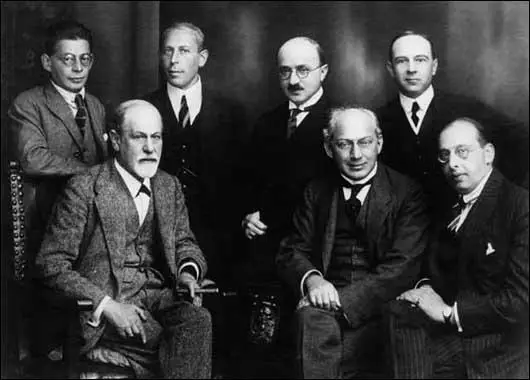

Front row, Sigmund Freud, Granville Stanley Hall and Carl Jung (September 1909)

As a result of these scandals he went to live in Toronto. As well as setting up as a psychoanalyst he gave lectures on the subject in both Canada and the United States. He met Granville Stanley Hall, the President of Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, who had done much to popularize psychology, especially child psychology, in in the United States, and was the author of Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education (1904). Hall was a great supporter of Sigmund Freud and in December, 1908, he invited him to deliver a series of lectures at the university. (8)

In August 1909, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and Sandor Ferenczi sailed to America. Ernest Jones travelled from Toronto, to join them. While watching the waving crowds from the deck of his ship as it docked in New York City, he turned to Jung and said, "Don't they know we're bringing them the plague?" (9) The following month Freud gave five lectures in German. He later recalled: "At that time I was only fifty-three. I felt young and healthy, and my short visit to the new world encouraged my self-respect in every way. In Europe I felt as though I were despised; but over there I found myself received by the foremost men as an equal." (10)

He also helped to organize the "First Congress for Freudian Psychology" in Salzburg. In March 1910 he took part in the International Psychoanalytical Congress at Nuremberg. Its first President was Carl Jung. "To begin with, Jung with his commanding presence and soldierly bearing looked the part of the leader. With his psychiatric training and position, his excellent intellect and his evident devotion to the work, he seemed far better qualified for the post than anyone else." (11)

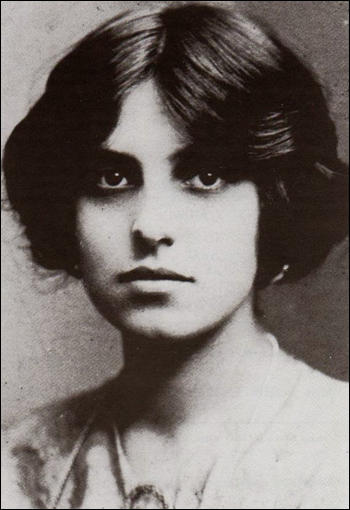

Seated, left to right, Sigmund Freud, Sandor Ferenczi and Hanns Sachs.

After helping to establish the American Psychoanalytic Association he returned to London in 1913 and was practicing psychoanalysis and organizing a small band of followers of Freud. In November, he reported to Freud that along with David Eder he helped to establish the London Psycho-Analytic Society. He explained it was duly constituted last Thursday, with a membership of nine." (12)

In 1913 Jones underwent a seven-week analysis with Sándor Ferenczi. On his return to London he established himself in private practice as a psychoanalyst. He lived in a flat at 69 Portland Court, Marylebone, and had a consulting room in Harley Street. (13)

Ernest Jones main objective was to promote the ideas of Freud. According to Peter Gay: "Jones was the most persuasive of popularizers and the most tenacious of polemicists... His commitment to psychoanalysis was wholehearted" (14) Freud told him: "There are few men so fitted to deal with with the arguments of others." (15)

Carl Jung had his doubts about Jones and wrote to Freud pointing out: Jones is a puzzling human being to me. I find him uncanny, incomprehensible. Is there a great deal to him, or too little? In any event, he is not a simple man, but an intellectual liar... too much of an admirer on the one hand, too much of an opportunist on the other?" (16) Freud replied: "I found him a fanatic who smiles at me for being timid...If he is a liar, he lies to the others, not to us... He is a Celt and hence not quite accessible to us, the Teuton and the Mediterranean man." (17)

In May 1912 Freud and Jung became involved in a dispute over the meaning of the incest taboo. Freud now realised that his relationship was at breaking point. Freud now had a meeting with his loyal followers, Ernest Jones, Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi and Hanns Sachs and it was decided to form a "united small body, designed... to guard the kingdom and policy of the master". (18)

The final break came when Jung made a speech at Fordham University where he rejected Freud's theories of childhood sexuality, the Oedipus complex and the role of sexuality in the formation of neurotic illness. In a letter to Freud, he argued that his vision of psychoanalysis had managed to win over many people who had hitherto been put off by "the problem of sexuality in neurosis". He said that he hoped that friendly personal relations with Freud would continue, but in order for that to happen he did not want resentment but objective judgments. "With me this is not a matter of caprice, but of enforcing what I consider to be true." (19)

In late November 1912, Jung and Freud met at a conference in Munich. The reunion was marred by one of Freud's fainting spells. This was a repeat on what happened at their last meeting. "Suddenly, to our consternation, he fell on the floor in a dead faint. The sturdy Jung swiftly carried him to a couch in the lounge, where he soon revived." (20) In letters he sent to friends, Freud claimed that "the principal agent in his fainting was a psychological conflict". However, in a letter to Jung he said the fainting was caused by a migraine. (21)

After receiving a letter from Jung in December, 1912, Sigmund Freud told Ernest Jones that "he (Jung) seems all out of his wits, he is behaving quite crazy" and the "reconciliation" of November "has left no trace with him". However, he added he wanted no "official separation", for the sake of "our common interest" and advised Jones to take "no more steps to his conciliation". He suggested Jones did not make contact with Jung as he would probably say "I was the neurotic... It is the same mechanism and the identical reaction as in Adler's case." (22)

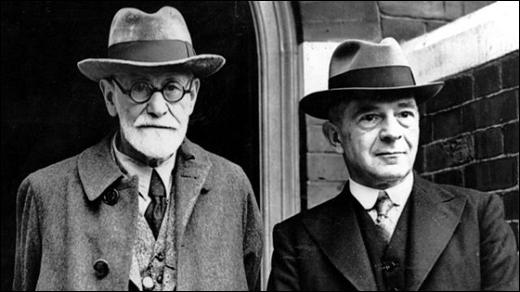

Anna Freud

Freud's 19-year-old daughter, Anna Freud, visited England in the summer of 1914. Before she left, Freud warned her against the attentions of Ernest Jones who was looking after her in London. "I know from the best sources that Dr. Jones has serious intentions of seeking your hand." He added that she should "discourage any courting yet avoid all personal offence." (23)

Freud also wrote to the 35 year-old Jones, explaining that he should not make any sexual advances towards his daughter. "She is the most gifted and accomplished of my children, and a valuable character besides, full of interest for learning, seeing sights and getting to understand the world... She does not claim to be treated as a woman, being still far away from sexual longings and rather refusing man. There is an outspoken understanding between me and her that she should not consider marriage or the preliminaries before she gets 2 or 3 years older. I don't think she will break this treaty." (24)

Peter Gay has argued that "this treaty" was an agreement to "postpone thinking seriously about men". Freud had told others that Anna was emotionally younger than her age. "Yet to claim that Anna, a fully grown young woman, lacked any sexual feelings was to sound like a conventional bourgeois who had never read Freud. One might take this to be part of Freud's hint that for Jones to put his hands on Anna would be equivalent to child abuse... Freud's denial of his daughter's sexuality is transparently out of character; it reads like the surfacing of a wish that his little girl remain a little girl - his little girl." (25)

Anna Freud obediently followed her father's instructions, but she did become close to Loe Kann, Jones's attractive mistress, who was a morphine addict who had been analyzed by Sigmund Freud, two years earlier. It has been claimed that Anna found Kann more attractive than Jones. (26) On the outbreak of war, she returned to Vienna accompanied by the Austrian ambassador. (27)

First World War

On 28th June, 1914, the world was shocked by the news that the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, had been assassinated in Sarajevo. Ferdinand was due to inherit the position held by Emperor Franz Josef. As Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy were members of the Triple Alliance, some feared the assassination would lead to war. Freud wrote to his close friend, Sandor Ferenczi: "I am writing while still under the impact of the astonishing murder in Sarajevo, the consequences of which cannot be foreseen." (28)

Ernest Jones suggested that one would have expected that a fifty-eight rear old pacifist would have greeted the news of the declaration of war with "simple horror". Jones goes on to explain: "On the contrary, his first response was rather one of youthful enthusiasm, apparently a reawakening of the military ardours of his boyhood. He said that for the first time in thirty years he felt himself to be an Austrian." (29)

He wrote to Karl Abraham that he would support the First World War "with all my heart, if I did not know that England is on the wrong side". (30). He replied that it was strange that their great friend, Ernest Jones, was now an "enemy" as he was English. (31) Freud came to the conclusion that he should remain in contact with his English supporters, although he insisted he would write in German. He told Jones: "It has been generally decided not to regard you as an enemy". (32)

On 6th February 1917, Ernest Jones married Morfydd Llwyn Owen, a Welsh musician. The following year, while travelling in Wales, she had an acute attack of appendicitis. On the advice of his friend, Wilfred Trotter, he immediately conducted the surgery together with a local surgeon, using chloroform in the operation. Jones later wrote that after a few days she became delirious with a high temperature. "We thought there was blood poisoning till I got Trotter from London. He at once recognized delayed chloroform poisoning. It had recently been discovered which neither the local doctor nor I had known, that this is a likelihood with a patent who is young, has suppuration in any part of the body, and has been deprived of sugar (as war conditions had then imposed); in such circumstances only ether is permissible as an anesthetic. This simple piece of ignorance cost a valuable and promising life. We fought hard, and there were moments when we seemed to have succeeded, but it was too late." She died on 7th September, 1918. (33)

The following year, Hanns Sachs, introduced Jones to Katharina Jokl. She had been raised in Vienna and studied in Switzerland. Mervyn Jones, his son, later recalled: "They were engaged in three days and married within three weeks... The happiness which my father was of a quality far more often envied than attained. His affection for and gratitude to her were only strengthened by time." (34)

London Psycho-Analytic Society

Carl Jung had many followers in the London Psycho-Analytic Society. This included David Eder, Maurice Nicoll and Constance Long. In 1919 dissolved the London society and expelled what he called the "Jung rump". The purged and reformed society was renamed the British Psycho-Analytical Society. Shortly after its foundation Jones informed Freud that he had personally analysed six of its eleven members. (35)

One of his early patients was Prynce Hopkins, had analysis with Jones shortly after the First World War, recalled him as a man of "short stature, broad head and forehead, thin lips and pale but energetic appearance" Hopkins gave the following picture of Jones at work: "Dr. Jones' consulting room was large, but unlike his mentor, Freud, it was nearly bare of furniture and very gloomy, out of sight, behind my head, Dr. Jones sat back in his big easy chair, usually with a rug across his legs, gazing at the wall or fire." (36)

In 1920 Jones founded the International Journal for Psychoanalysis, which was the first English-language periodical devoted to psychoanalysis. He remained its editor for the next nineteen years. In 1924, together with John Rickman, he established the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London. In 1926, thanks to a donation of £10,000 from his patient Prynce Hopkins, the London Clinic of Psycho-Analysis was formed, which enabled low-cost psychoanalytic treatment. Jones became its honorary director. According to his biographer, Sonu Shamdasani: "Thus Jones effectively occupied most of the positions of power in British psychoanalysis, centralizing authority upon himself. In addition to his central role in Britain, Jones was the president of the International Psycho-Analytical Association from 1920 to 1924." (37)

In September, 1926, Melanie Klein, a member of the Berlin Psychoanalytical Society, accepted the invitation of Ernest Jones, to analyse his children in London. She lived in a maisonette near the Institute of Psychoanalysis in Gloucester Place. Her practice soon included not only Jones's children and wife but also six other patients. She now decided to settle permanently in England, a place that she described as "her second motherland". (38)

Nazi Germany

In June 1933 the German Society for Psychotherapy (GSP) came under the control of the Nazi Party. It was now led by Matthias Göring, a cousin of Hermann Göring, and a leading member of Hitler's government. Matthias Göring told all members that they were expected to make a thorough study of Mein Kampf, which was to serve as the basis for their work. Ernst Kretschmer, the president of the GSP, promptly resigned and was replaced by Carl Jung. (39)

On 12th March, 1938, Adolf Hitler announced Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany). Freud believed that the powerful Catholic Church would protect the Jewish community. This did not happen and as the German playwright Carl Zuckmayer, pointed out: "The underworld had opened its gates and let loose its lowest, most revolting, most impure spirits. The city was transformed into a nightmare painting by Hieronymus Bosch... and the air filled with an incessant, savage, hysterical screeching from male and female throats... resembling distorted grimaces: some in anxiety, others in deceit, still others in wild, hate-filled triumph." (40)

Journalists from Britain and America were shocked by the immediate persecution of Jews in Austria. "SA men dragged an elderly Jewish worker and his wife through the applauding crowd. Tears rolled down the cheeks of the old woman, and while she stared ahead and virtually looked through her tormentors, I could see how the old man, whose arm she held, tried to stroke her hand." A man who had been living in Berlin "expressed some astonishment at the speed with which anti-Semitism was being introduced here, which he said was going to make the plight of the Vienna Jews far worse than it was in Germany, where the change had come with a certain gradualness". (41)

During the spring of 1938, it was reported that some 500 Austrian Jews chose to kill themselves to avoid humiliation, unbearable anxiety, or deportation to concentration camps. In March the authorities felt compelled to issue a denial of the "rumours of thousands of suicides since the Nazi accession to power." The press release added that "from March 12 to March 22 ninety-six persons committed suicide in Vienna of whom only fifty were directly connected with the change in the political situation in Austria." (42)

Ernest Jones flew to Vienna in an effort to persuade Sigmund Freud to move to England. At first he said he was too old to travel. He also commented that "he could not leave his native land; it would be like a soldier deserting his post". Eventually he agreed and Jones returned to London on 20th March, to have talks with friends in the government, including Sir Samuel Hoare, the home secretary, and Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, lord privy seal.

On 22nd March, 1938, Anna Freud was told that she had to appear at Gestapo headquarters in Vienna. Max Schur, Freud's personal doctor, was supplied with a sufficient amount of the poison veronal. Schur later recalled: "I stayed with Freud (while she was with the Gestapo)... The hours were endless. It was the only time I ever saw Freud deeply worried. He paced the floor, smoking incessantly. I tried to reassure him as well as I could." During the interrogation, she managed to persuade them the International Psychoanalytic Association was an unpolitical organisation and she was released. (43)

This incident convinced Freud that his family should move to London. One of the conditions for being granted an exit visa was that he sign a document that ran as follows, "I Prof. Freud, hereby confirm that after the Anschluss of Austria to the German Reich I have been treated by the German authorities and particularly the Gestapo with all the respect and consideration due to my scientific reputation, that I could live and work in full freedom, that I could continue to pursue my activities in every way I desired, that I found full support from all concerned in this respect, and that I have not the slightest reason for any complaint." It was later claimed Freud agreed to sign the document but asked if he might be allowed to add a sentence, which was: "I can heartily recommend the Gestapo to anyone". (44)

The Gestapo agreed that he could go to England as long as all his debts were paid. Marie Bonaparte agreed to do this and on 4th June the Freud party left on the Orient Express. On 6th June the Freuds crossed over to England by the night boat. On their arrival, Anna Freud told the Manchester Guardian that "in Vienna we were among the very few Jews who were treated decently. It is not true that we were confined to our home. My father never went out for weeks, but that was on account of his health. The general treatment of the Jews has been abominable, but not so in case of my father. He has been an exception." (45)

Death of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud's health remained poor. A biopsy performed on 28th February, 1939, showed that the cancer had returned but it was so far back in the mouth an operation was considered to be impossible. In a letter to Arnold Zweig he complained that since his last operation "I have been suffering from pains in the jaw which are growing stronger slowly but steadily, so that I cannot get through my daily chores and my nights without a hot-water bottle and sizable doses of aspirin." (46)

Max Schur, Freud's personal doctor, had been treating him since March 1929. The main source of conflict between the two men was Freud's refusal to give up his beloved, necessary cigars. At their first meeting Freud asked him to "promise... when the time comes, you won't let them torment me unnecessarily." Schur agreed and the two men shook hands on it." (47)

On 21st September, as Schur was sitting by his bedside, Freud took his hand and said to him: "Schur, you remember our contract not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense." When he replied that he had not forgotten, he said "I thank you" and added "Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it's right, then make an end of it." Anna Freud wanted "to postpone the fatal moment, but Schur insisted that to keep Freud going was pointless". He pointed out that Freud wanted to keep control of his life to the end. (48)

Schur injected Freud with three centigrams of morphine - the normal dose for sedation was two centigrams - and Freud sank into a peaceful sleep. Schur repeated the injection later that day and administered a final one the next day. Freud lapsed into a como from which he did not wake. Sigmund Freud died at three in the morning on 23rd September, 1939. (49)

Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (1953-1957)

During the Second World War Jones moved to his country house, "The Plat", at Elsted, near Chichester, in semi-retirement, with only a few wealthy patients. After the war he started work on his The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, which appeared in three volumes in 1953, 1955, and 1957. "This was his most significant literary achievement. In preparation for it Jones had unrivalled access to Freud's papers, many of which remain inaccessible to scholars to this day." (50)

Jones was aided by the fact that his wife, Katharina Jokl, was a native German speaker and she transcribed over a thousand letters of Freud for him. His son, Mervyn Jones, pointed out: "I can only affirm, and cannot express as he would have, the degree to which he loved and valued her as a wife, as an unfailing support in times of strain, and as an especially in preparing the Freud biography." (51)

The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud remains the single most important biographical source of information on Freud's life and on the early history of the psychoanalytic movement. No other single work has been more influential in shaping the subsequent perception of Freud. However, Lisa Appignanesi, the author of Freud's Women (1995) has described the book as a "magnificent, if somewhat hagiographical, biography of Freud". (52)

Jones definitely used the book to attack Freud's opponents such as Alfred Adler, Carl Jung and Otto Rank, who were "represented as heretics, whose original ideas stemmed from personal psychopathology and character defects". Whereas his followers "especially Jones himself, were portrayed as a revolutionary vanguard that fought against vicious and malevolent opponents, widespread prejudice, and obscurantism". (53)

In 1956 Ernest Jones contracted cancer of the bladder. Two years later he developed cancer of the liver. He died in University College Hospital on 11th February 1958, and was cremated at Golders Green three days later. At his death he left an uncompleted manuscript of his autobiography. This was edited by his son, Mervyn Jones, and published as Free Associations: Memories of a Psycho-Analyst in 1959.

Primary Sources

(1) Sonu Shamdasani, Ernest Jones : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

In 1896 Jones began the first part of his medical studies at University College, Cardiff, which he continued in 1898 at University College Hospital, London. Through his readings, and particularly through the influence of the works of Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and Kingdom Clifford, he became committed to an evolutionary, materialistic, and atheistic world view. He obtained his BM (1901), BS (1902), MD (1903), and became MRCP (1904). He initially attempted to establish himself as a neurologist, and was heavily influenced by the work of John Hughlings Jackson. However, he had difficulty obtaining a secure position, and held house posts in medicine and surgery at University College Hospital, followed by various posts at the Brompton Chest Hospital, the National Hospital, the Hospital for Sick Children, the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital, the West End Hospital for Nervous Diseases, Moorfields Eye Hospital, the North-Eastern Hospital for Children, the Farringdon General Dispensary and the Dreadnought Seamen's Hospital at Greenwich. His career ran into difficulties, and he failed to obtain an expected appointment at University College Hospital. In 1905 he set up a practice as a consultant physician in Harley Street, together with his best friend, the surgeon Wilfred Batten Lewis Trotter (1872–1939), who married Jones's sister Elizabeth in 1910. During this time Jones published a number of papers on neurological topics.In 1906 Jones was accused of sexually assaulting two girls - a charge of which he was subsequently cleared. In 1908 he was asked to resign his post at the West End Hospital for Nervous Diseases after examining a ten-year-old girl and discussing sexual topics without the presence of a third person (Jones, Free Associations; Brome; Paskauskas, Ernest Jones). During this period he became interested in psychopathology and in particular read widely in the French literature on hypnotism, double personality, and hysteria.

(2) Peter Gay, Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989)

Ernest Jones discovered Freud not long after the publication of the case history of Dora in 1905. As a young physician specializing in psychiatry, he had been sorely disappointed by the failure of contemporary medical orthodoxy to explain the workings, and the malfunctioning, of the mind, so that disappointment facilitated his conversion. At the time he read about Dora, his German was still halting, but he "came away" from his reading "with a deep impression of there being a man in Vienna who actually listened to every word his patients said to him." It came as a revelation. "I was trying to do so myself, but I had never heard of anyone else doing so." Freud, he recognized, was that "rara avis, a true psychologist."

After spending some time with Jung at Burgholzli learning more alb psychoanalysis, Jones sought out Freud in the spring of 1908 at the Salzburg congress of psychoanalysts, where he heard Freud give a memorable address on one of his patients, the Rat Man. Wasting no time, he followed up this meeting in May with a visit to Berggasse 19, where he was cordially recwived. After that, he and Freud saw one another often and bridged the gaps between meetings with long, frequent communiques. Some years of distressing inner battles followed for Jones; he was besieged with doubts about psychoanalysis. But once sure of his ground, once fully persuaded, he made himself into the most energetic of Freud's advocates, first in North America, then in England, in the end everywhere.

That Jones started his campaign in behalf of Freud's ideas in Canada and the northeastern United States was not wholly a matter of free choice. The breath of scandal hangs over his early medical career in London: Jones was twice accused of misbehaving with children he was testing and examining. Dismissed from his post at a children's hospital, he thought it prudent to move to Toronto. Once settled, he began lecturing on psychoanalysis to generally unreceptive audiences in Canada and the United States, and in 1911 he was active in founding the American Psychoanalytic Association.