On this day on 21st January

On this day in 1840 feminist Sophia Jex-Blake, the daughter of Thomas Jex-Blake and Mary Cubitt, was born at 3 Croft Place, Hastings. Thomas Jex-Blake was a successful barrister, but he had retired at the time of her birth.

In 1851 the family moved to 13 Sussex Square, Brighton. Sophia attended several private boarding-schools as a child. Sophia's parents were Evangelical Anglicans who held very traditional views on education and at first refused permission for her to study at college.

Eventually Dr. Jex-Blake gave his permission and in 1858 Sophia began attending classes at Queen's College in Harley Street. Two of her fellow students were Dorothea Beale and Frances Mary Buss. One of her teachers was the Reverand John Maurice, one of the founders of the Christian Socialist movement. He told her: "The vocation of a teacher is an awful one… she will do others unspeakable harm if she is not aware of its usefulness… How can you give a woman self-respect, how can you win for her the respect of others… Watch closely the first utterances of infancy, the first dawnings of intelligence; how thoughts spring into acts, how acts pass into habits. The study is not worth much if it is not busy about the roots of things."

Sophia did so well that she was asked to become a tutor of mathematics at the college. Sophia's parents believed it was wrong for middle-class women to work and only gave their approval after she agreed not to accept a salary. During this period she shared a house in Nottingham Place with Octavia Hill and her family.

While in London became friends with a group of feminists that included Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett, Adelaide Anne Procter, and Emily Faithfull. According to Louisa Garrett Anderson: "They were comrades and worked for a great end." Eventually, most of these women became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage.

In 1862 Jex-Blake spent several months in Edinburgh being taught by private tutors. She also helped Elizabeth Garrett to prepare her application to University of Edinburgh for enrolment as a medical student. The two had previously met in London, but during Elizabeth's visit to Edinburgh, Jex-Blake learned more about the problems facing women who wished to practise medicine.After Queen's College, Sophia spent time teaching in Germany and the United States. When she returned she wrote a book about his experiences A Visit to Some American Schools and Colleges (1867). Sophia had been especially impressed with the experiments in the United States with co-education. While in America she met Dr. Lucy Sewell, the resident physician at the New England Hospital for Women. Sophia now decided she would rather be a doctor rather than a teacher.

Sophia Jex-Blake wrote a pamphlet, Medicine as a Profession for Women (1869), where she argued the case for women doctors: "One argument usually advanced against the practice of medicine by women is that there is no demand for it; that women, as a rule, have little confidence in their own sex, and had rather be attended by a man… it is probably a fact, that until lately there has been no demand for women doctors, because it does not occur to most people to demand what does not exist; but that very many women have wished that they could be medically attended by those of their own sex I am very sure, and I know of more than one case where ladies have habitually gone through one confinement after another without proper attendance, because the idea of employing a man was so extremely repugnant to them."

Sophia Jex-Blake began to explore the possibility of training as a doctor. This was a problem as British medical schools refused to accept women students. She eventually persuaded University of Edinburgh to allow her and her friend, Edith Pechy, to attend medical lectures. This annoyed the male students and attempts were made to stop them receiving teaching and taking their examinations. As Jex-Blake later pointed out: "On the afternoon of Friday 18th November 1870, we walked to the Surgeon's Hall, where the anatomy examination was to be held. As soon as we reached the Surgeon's Hall we saw a dense mob filling up the road… The crowd was sufficient to stop all the traffic for an hour. We walked up to the gates, which remained open until we came within a yard of them, when they were slammed in our faces by a number of young men." Shirley Roberts adds: "Then a sympathetic student emerged from the hall; he opened the gate and ushered the women inside. They took their examination and all passed." Although Jex-Blake and Pechy both passed their examinations, university regulations only allowed medical degrees to be given to men. The British Medical Association therefore refused to register the women as doctors.

Sophia Jex-Blake's case generated a great deal of publicity and Russell Gurney, a M.P. who supported women's rights, decided to try and change the law. In 1876 Gurney managed to persuade Parliament to pass a bill that empowered all medical training bodies to educate and graduate women on the same terms as men. The first educational institution to offer this opportunity to women was the Irish College of Physicians. Sophia took up their offer and qualified as a doctor in 1877.

In June 1878, Jex-Blake opened a medical practice at 4 Manor Place; three months later she established a dispensary (an out-patient clinic) for impoverished women at 73 Grove Street, Fountainbridge. These ventures were highly successful but after the death of one of her assistants, she suffered from depression. She closed her practice and left the dispensary in the care of her medical colleagues.

Sophia Jex-Blake remained inactive for several years but eventually decided to join forces with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in her efforts to establish a Medical School for women. In 1887 they opened the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. In its second year the school was disrupted by disputes between Jex-Blake and several of the students who resented her imposition of strict rules of conduct.

One of her close friends, Dr Margaret Todd, the author of The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake (1918), once said: "She was impulsive, she made mistakes and would do so to the end of her life: her naturally hasty temper and imperious disposition had been chastened indeed, but the chastening fire had been far too fierce to produce perfection … But there was another side to the picture after all. Many of those who regretted and criticised details were yet forced to bow before the big transparent honesty, the fine unflinching consistency of her life." While in Edinburgh, Sophia played an active role in the local Women's Suffrage Society.

When Dr. Jex-Blake, dismissed two students for what Elsie Inglis considered to be a trivial offence, she obtained funds from her father and some of his wealthy friends, and established a rival medical school, the Scottish Association for the Medical Education for Women.

In 1899 Sophia Jex-Blake retired to Windydene, a small farm at Mark Cross, some 5 miles south of Tunbridge Wells. Sophia Jex-Blake continued to campaign for women's suffrage until her death at Windydene on 7th January 1912.

On this day in 1846 Charles Dickens published the first edition of The Daily News. Dickens was a supporter of the Liberal Party and in 1845 he began to consider the idea of publishing a daily newspaper that could compete with The Times. He contacted Joseph Paxton, who had recently become very wealthy as a result of his railway investments. Paxton agreed to invest £25,000 and Dickens' publishers, Bradley & Evans, contributed £22,500. Dickens agreed to become editor on a salary of £2,000 a year.

The the first edition Dickens wrote: "The principles advocated in the Daily News will be principles of progress and improvement; of education, civil and religious liberty, and equal legislation." Dickens employed his great friend and fellow social reformer, Douglas Jerrold, as the newspaper's sub-editor. Dickens put his father, John Dickens, in charge of the reporters. He also paid his father-in-law, George Hogarth, five guineas a week to write on music.

William Macready wrote in his diary that John Forster told him that The Daily News would greatly injure Dickens: "Dickens was so intensely fixed on his own opinions and in his admiration of his own works (who could have believed it?) that he, Forster, was useless to him as a counsel, or for an opinion on anything touching upon them, and that, as he refused to see criticisms on himself, this partial passion would grow upon him, till it became an incurable evil."

One of the newspaper's first campaigns was against the Corn Laws, that had been introduced by the Conservative Party government. When Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, told the House of Commons that he had changed his mind about the legislation, Dickens did not believe him and wrote in the editorial that he was "decidedly playing false".

The Times had a circulation of 25,000 copies and sold for sevenpence, whereas The Daily News, provided eight pages for fivepence. At first it sold 10,000 copies but soon fell to less than 4,000. Dickens told his friends that he missed writing novels and after seventeen issues he handed it over to his close friend, John Forster. The new editor had more experience of journalism and under his leadership sales increased. John Wentworth Dilke, the former editor of The Athenaeum also joined the paper. Over the years many of the leading writers with Liberal opinions contributed to the newspaper, including figures such as Charles Mackay, Harriet Martineau, George Bernard Shaw, Henry Massingham and H. G. Wells.

In 1901 The Daily News was purchased by George Cadbury, the Quaker owner of Cadbury Brothers and a strong supporter of William Gladstone and the Liberal Party. Cadbury used the newspaper to campaign for old age pensions and against sweated labour. As a pacifist, Cadbury and the newspaper were opposed to the Boer War.

The Daily News was absorbed by the Daily Chronicle in 1930 became the News Chronicle. It continued publishing under this name until it closed in 1960.

On this day in 1864 Israel Zangwill, was born in Whitechapel. He was the second of the five children of Moses Zangwill, an itinerant pedlar, glazier, and rabbinical student, and his wife, Ellen Hannah Marks, a Polish Jewish immigrant.

He attended the Jews' Free School in Spitalfields. After receiving his degree at the University of London he returned to his school as a teacher. In June 1888 he resigned from his teaching position to become a journalist on the staff of the newly founded weekly newspaper the Jewish Standard.

His first novel, The Bachelors' Club, was published in 1891. His short-stories appeared in various magazines including The Idler, a magazine edited by his friend from university, Jerome K. Jerome. He was also editor of The Puck Magazine, a comic journal which folded in February 1892.

The publication of Children of the Ghetto (1892), according to one critic, "with its powerful realistic depiction of ghetto life, established Zangwill as a spokesperson for Jewry within and outside the Jewish world." This was followed by Ghetto Tragedies (1893), The King of Schnorrers: Grotesques and Fantasies (1894) and Dreamers of the Ghetto (1898).

In 1903 Zangwill married Edith Ayrton, the daughter of the physicist William Edward Ayrton and stepdaughter of Ayrton's second wife, Hertha Ayrton. Edith's mother, Matilda Chaplin Ayrton (1846-1883), had been a doctor and a member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage. Edith was brought up by Hertha, who was Jewish.

With her husband's encouragement Edith published a novel, Barbarous Babe in 1904. This was followed by The First Mrs Mollivar (1905). Edith shared her stepmother's support for women's suffrage and became a member of the NUWSS. The couple had three children: George (born 1906), who became an engineer and worked in Mexico; Margaret (1910), who suffered from a mental condition and was institutionalized and Oliver (1913), who became professor of experimental psychology at the University of Cambridge.

Frustrated by the lack of progress in achieving the vote Edith Zangwill and Hertha Ayrton accepted that a more militant approach was needed and in 1907 they joined the Women Social & Political Union. In a letter she wrote to Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Hertha admitted: "I made up my mind some time ago that as I am unable to be militant myself, from reasons of health, and as I believe most fully in the necessity for militancy, I was bound to give every penny I can afford to the militant union that is bearing the brunt of the battle, namely the WSPU."

On 9th February 1907, Zangwill shared a platform with Keir Hardie on the subject of women's suffrage. Sylvia Pankhurst recorded: "When Mr. Zangwill came to speak, he.... declared himself to be a supporter of the militant tactics and the anti-Government policy, and the same Liberal ladies (who had hissed Keir Hardie), although they had themselves asked him to speak for them, expressed their dissent and disapproval as audibly as though they had been Suffragettes and he a Cabinet Minister."

Zangwill was criticised for supporting the militant tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. To the charge that members were "unwomanly" he replied that "ladylike means are all very well if you are dealing with gentlemen; but you are dealing with politicians". He added that "for every government - Liberal or Conservative - that refuses to grant female suffrage is ipso facto the enemy."

In 1907, several left-wing intellectuals, including Israel Zangwill, Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Hugh Franklin, Charles Mansell-Moullin, Herbert Jacobs, and 32 other men formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men." Evelyn Sharp later argued: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Landsbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

In November 1912 Israel Zangwill and Edith Zangwill helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage. The main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society." Other members included Henrietta Franklin, Hugh Franklin, Lily Montagu and Inez Bensusan.

In November 1913, Zangwill wrote an article for The English Review where he rejected militancy for its own sake as dramatic but not politically effective, and criticised the increased lack of democracy in the Women Social & Political Union. Zangwill especially disapproved of the arson campaign of the WSPU and in February 1914 helped to establish the non-militant United Suffragists.

Zangwill was a strong supporter of Zionism. His biographer, Joseph H. Udelson, the author of Dreamer of the Ghetto: the Life and Works of Israel Zangwill (1990) has argued "From 1901 to 1905 (Zangwill) was an advocate of official Herzlian Zionism; from 1905 to 1914 he was the driving force behind insurgent Territorialism; and from 1914 to 1919 he was the leading Western advocate of a Palestine-centred Jewish nationalism". On 16th January, 1920 The Times published a letter from Zangwill: "What is now being concocted in Paris (that is, a League of Nations mandate) is a scheme without attraction save for mere refugees, a scheme under which a free-born Jew returning to Palestine would find himself under British military rule, aggravated by an Arab majority in civic affairs." Alfred Sutro observed that: "under a somewhat truculent exterior he was curiously unselfish and tender-hearted… A fiery spirit, a man who all his life followed a great idea."

Another biographer, William Baker, has argued: "Zangwill was angular, tall, gaunt, and bespectacled, and was a witty, powerful and epigrammatic speaker who attracted large audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to his novels he translated the Hebrew liturgy into English and wrote poetry and twenty dramas - many of which were adaptations from his novels."

Suffering from poor health he retired to his home at Far End, East Preston. His biographer, Joseph Udelson, the author of Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990), has pointed out: " Zangwill's physical and mental health deteriorated seriously during the following two months as the incessant insomnia and anxiety acted upon his always fragile physical constitution. No longer capable of doing any work, he was confined to his home."

Israel Zangwill died of pneumonia on 1st August 1926 at Oakhurst, a nursing home in Midhurst, West Sussex.

On this day in 1870 philosopher Alexander Herzen died. Herzen, the illegitimate son of Ivan Yakovlev, a wealthy member of the nobility, was born in Moscow, Russia, on 25th March, 1812, and was the heir to a considerable fortune. According to Isaiah Berlin: "Ivan Yakovlev, a rich and well-born Russian gentleman... a morose, difficult, possessive, distinguished and civilized man, who bullied his son, loved him deeply, embittered his life, and had an enormous influence upon him both by attraction and repulsion."

As a child he had deep sympathy for the serfs under the control of his father and uncle. Herzen explains in his autobiography, My Past and Thoughts (1867)" Neither my father nor my uncle was specially tyrannical, at least in the way of corporal punishment. My uncle, being hot-tempered and impatient, was often rough and unjust... A commoner form of punishment was compulsory enlistment in the Army, which was intensely dreaded by all the young men-servants. They preferred to remain serfs, without family or kin, rather than carry the knapsack for twenty years. I was strongly affected by those horrible scenes: at the summons of the land-owner, a file of military police would appear like thieves in the night and seize their victim without warning." These experiences developed in Herzen a deep sympathy for the peasants and became an advocate of social reform.

One of his tutors, Ivan Protopopov, introduced him to the work of Alexander Pushkin and Kondraty Ryleyev (a poet who had been executed for his role in the Decembrist Revolt that attempted to overthrow Tsar Nicholas I in 1825. "This man was full of that respectable indefinite liberalism, which, though it often disappears with the first grey hair, marriage, and professional success, does nevertheless raise a man's character... He began to bring me manuscript copies, in very small writing and very much frayed, of Pushkin's poems - Ode to Freedom, The Dagger, and of Ryleyev's Thoughts. These I used to copy out in secret."

In 1827 Alexander Herzen became friends with Nikolay Ogarev. Herzen commented in his autobiography: "I do not know why people dwell exclusively on recollections of first love and say nothing about memories of youthful friendship. First love is so fragrant, just because it forgets difference of sex, because it is passionate friendship. Friendship between young men has all the fervour of love and all its characteristics - the same shy reluctance to profane its feeling by speech, the same diffidence and absolute devotion, the same pangs at parting, and the same exclusive desire to stand alone without a rival."

Herzen was educated at the University of Moscow. He studied mathematics and physics: "I never had any great turn or much liking for mathematics, Nikolay and I were taught the subject by the same teacher, whom we liked because he told us stories; he was very entertaining, but I doubt if he could have developed a special passion in any pupil for his branch of science... I chose that Faculty, because it included the subject of natural science, in which I then took a specially strong interest."

While at university Herzen mixed in radical circles: "The pursuit of knowledge had not yet become divorced from realities, and did not distract our attention from the suffering humanity around us; and this sympathy heightened the social morality of the students. My friends and I said openly in the lecture-room whatever came into our heads; copies of forbidden poems were freely circulated, and forbidden books were read aloud and commented on; and yet I cannot recall a single instance of information given by a traitor to the authorities."

Afterwards he worked at a girls' school run by French Catholic priests. One of his students was the 12 year-old Tanya Passek. She later recalled how Herzen's teaching was a revelation. At her previous school her education consisted of reading "volumes of incomprehensible hieroglyphics, the coldness and severity of the teachers and the constant fear of punishment: having to wear a dunce's cap, or being led on a string around the building". Herzen introduced Passek to the poetry of Alexander Pushkin.

Herzen's outspoken views on the need to bring an end to serfdom and autocratic rule resulted in him being arrested and sent into internal exile. In 1835 he was forced to work as a government official in Vyatka (now Kirov). Later he moved to Vladimir, where he was appointed editor of the city's official gazette. After criticizing the police he was sentenced to two years exile in Novogorod.

Herzen became friends with, Mikhail Bakunin, Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Ogarev. As Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976): "In the 1830s writers like Belinsky, Bakunin, Herzen and Ogarev, all consumed by the desire for philosophical certainties, were tentatively exploring the ideas of socialism within a framework of romantic culture.... Herzen's quasi-religious desire for inner peace prompted him to mediate between the more extreme philosophies of his friends. On the other hand there was Bakunin, whose radical interpretation of the theories of Fourier, Saint-Simon and Owen were to lead him to a more doctrinaire violence."

Another friend, Pavel Annenkov, commented: "I must own that I was puzzled and overwhelmed, when I first came to know Herzen - by this extraordinary mind which darted from one topic to another with unbelievable swiftness, with inexhaustible wit and brilliance; which could see in the turn of somebody's talk, in some simple incident, in some abstract idea, that vivid feature which gives expression and life. He had a most astonishing capacity for instantaneous, unexpected juxtaposition of quite dissimilar things, and this gift he had in a very high degree, fed as it was by the powers of the most subtle observation and a very solid fund of encyclopedic knowledge. He had it to such a degree that, in the end, his listeners were sometimes exhausted by the inextinguishable fireworks of his speech, the inexhaustible fantasy and invention, a kind of prodigal opulence of intellect which astonished his audience."

At the age of twenty-six he married his first cousin, Natalie Zakharina. In 1842 Herzen returned to Moscow and immediately joined those campaigning for reform. His wide-reading had radicalized him and he was now a supporter of the anarchist-socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Herzen believed that the peasants in Russia could become a revolutionary force and after the overthrow of the nobility would create a socialist society. This included the vision of peasants living in small village communes where the land was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines.

After receiving a large inheritance from his father, Herzen decided to leave Russia. He arrived in Paris in 1847 and witnessed the political struggles that resulted in the 1848 Revolution. His commentary on the failed European revolutions, From the Other Shore, was published in 1850. Herzen wrote: "In nature, as in the souls of men, there slumber endless possibilities and forces, and in suitable conditions... they develop, and will develop furiously. They may fill a world, or they may fall by the roadside. They may take a new direction. They may stop. They may collapse... Nature is perfectly indifferent to what happens... But then, you may ask, what is all this for?... To look at the end and not at the action itself is a cardinal error. Of what use to the flower is its bright magnificent bloom? Or this intoxicating scent, since it will only pass away?... None at all. But nature is not so miserly. She does not disdain what is transient, what is only in the present. At every point she achieves all she can achieve ... Who will find fault with nature because flowers bloom in the morning and die at night, because she has not given the rose or the lily the hardness of flint? And this miserable pedestrian principle we wish to transfer to the world of history... Life has no obligation to realise the fantasies and ideas of civilisation... Life loves novelty... History seldom repeats itself, it uses every accident, simultaneously knocks at a thousand doors... doors which may open... who knows?"

Herzen's biographer, Edward Acton, the author of Alexander Herzen and the Role of the Intellectual Revolutionary (1979) has argued: "One of the first members of the Russian intelligentsia to adopt socialism, he acknowledged a major debt to Fourier, the Saint-Simonians, Blanc and Proudhon. Initially he looked to the West to inaugurate an era of socialist justice and individual liberty. The failure of the Revolutions of 1848 affected him profoundly. His commentary on them, From the Other Shore (1850), ranks with those of Marx and Tocqueville. Its finest lines explored the tensions between an unqualified affirmation of the individual and the sacrifices demanded by the revolutionary cause."

In 1852 Herzen moved to London. The accession of Alexander II in 1855 gave Herzen hope that reform would take place in Russia and he established the Free Russian Press that published a series of journals including The Bell. Herzen predicted that because of its backward economy, socialism would be introduced into Russia before any other European country. "What can be accomplished only by a series of cataclysms in the West can develop in Russia out of existing conditions."

Alexander Herzen was joined in England by Mikhail Bakunin. The two men worked together on the journal until 1863 when Bakunin went to join the insurrection in Poland. The Bell was smuggled into Russia where it was distributed to those who favoured reform. According to Isaiah Berlin "Herzen... dealt with anything that seemed to be of topical interest. He exposed, he denounced, he derided, he preached, he became a kind of Russian Voltaire of the mid-nineteenth century. He was a journalist of genius, and his articles, written with brilliance, gaiety and passion, although, of course, officially forbidden, circulated in Russia and were read by radicals and conservatives alike."

Herzen's views expressed in the newspaper appeared fairly conservative to those embracing the ideas of revolutionary groups such as the People's Will and the Liberation of Labour. Herzen criticized the desire to impose a new system on the people arguing that the time had come to stop "taking the people for clay and ourselves for sculptors".

Herzen wrote that left-wing intellectuals should stop taking "the people for clay and ourselves for sculptors". On one occasion Louis Blanc, a committed socialist, said to Herzen that human life was a great social duty, that man must always sacrifice himself to society. Herzen asked him why? Blanc replied "Surely the whole purpose and mission of man is the well-being of society." Herzen retorted: "But it will never be attained if everyone makes sacrifices and nobody enjoys himself."

Herzen rejected the ideas of people like Karl Marx who promoted the idea that socialism was inevitable. As Isaiah Berlin points out: "The purpose of the struggle for liberty is not liberty tomorrow, it is liberty today, the liberty of living individuals with their own individual ends, the ends for which they move and fight and perhaps die, ends which are sacred to them. To crush their freedom, their pursuits, to ruin their ends for the sake of some vague felicity in the future which cannot be guaranteed, about which we know nothing, which is simply the product of some enormous metaphysical construction that itself rests upon sand, for which there is no logical, or empirical, or any other rational guarantee - to do that is in the first place blind, because the future is uncertain; and in the second place vicious, because it offends against the only moral values we know; because it tramples on human demands in the name of abstractions - freedom, happiness, justice - fanatical generalizations, mystical sounds, idolized sets of words."

In 1865 Herzen wrote: "Social progress is possible only under complete republican freedom, under full democratic equality. A republic that would not lead to Socialism seems an absurdity to us - a transitional stage regarding itself as the goal. On the other hand, Socialism which might try to dispense with political freedom would rapidly degenerate into an autocratic Communism." In another article he claimed: "Who will finish us off? The senile barbarism of the sceptre or the wild barbarism of communism, the bloody sabre, or the red flag? Communism will sweep across the world in a violent tempest - dreadful, bloody, unjust, swift."

Isaiah Berlin has argued: "The purpose of the struggle for liberty is not liberty tomorrow, it is liberty today, the liberty of living individuals with their own individual ends, the ends for which they move and fight and perhaps die, ends which are sacred to them. To crush their freedom, their pursuits, to ruin their ends for the sake of some vague felicity in the future which cannot be guaranteed, about which we know nothing, which is simply the product of some enormous metaphysical construction that itself rests upon sand, for which there is no logical, or empirical, or any other rational guarantee - to do that is in the first place blind, because the future is uncertain; and in the second place vicious, because it offends against the only moral values we know; because it tramples on human demands in the name of abstractions - freedom, happiness, justice - fanatical generalizations, mystical sounds, idolized sets of words."

Herzen believed that any socialist revolution in Russia would have to be instigated by the peasantry. According to Edward Acton: "Nineteenth-century Russia was overwhelmingly a peasant society, and it was to the peasantry that Herzen looked for revolutionary upheaval and socialist construction. Central to his vision was the existence of the Russian peasant commune. In most parts of the empire the peasantry lived in small village communes where the land was owned by the commune and was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines. In this he saw the embryo of a socialist society. If the economic burdens of serfdom and state taxation were to be removed, and the land of the nobility made over to the communes, they would develop into flourishing socialist cells."

Acton goes on to argue: "The oppression of the central state could be done away with altogether and replaced by a socialist society of independent, egalitarian communes. There was no need for Russia to follow in the footsteps of the West, to pass through the purgatory of capitalist, industrial and urban development or of bourgeois constitutional government. She could benefit from her late arrival on the historical scene and avoid the mistakes of others." Herzen's ideas later inspired the formation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Lenin was later to criticise the ideas of Herzen: "Herzen belonged to the generation of revolutionaries among the nobility and landlords of the first half of the last century.... His 'socialism' was one of the countless forms and varieties of bourgeois and petty-bourgeois socialism of the period of 1848, which were dealt their death-blow in the June days of that year. In point of fact, it was not socialism at all, but so many sentimental phrases, benevolent visions, which were the expression at that time of the revolutionary character of the bourgeois democrats, as well as of the proletariat, which had not yet freed itself from the influence of those democrats... Herzen’s spiritual shipwreck, his deep scepticism and pessimism after 1848, was a shipwreck of the bourgeois illusions of socialism. Herzen’s spiritual drama was a product and reflection of that epoch in world history when the revolutionary character of the bourgeois democrats was already passing away (in Europe), while the revolutionary character of the socialist proletariat had not yet matured."

Tom Stoppard has written about Herzen's relationship with Karl Marx: "Marx distrusted Herzen, and was despised by him in return. Herzen had no time for the kind of mono-theory that bound history, progress and individual autonomy to some overarching abstraction like Marx's material dialecticism. What he did have time for - and what bound Isaiah Berlin to him - was the individual over the collective, the actual over the theoretical. What he detested above all was the conceit that future bliss justified present sacrifice and bloodshed. The future, said Herzen, was the offspring of accident and wilfulness. There was no libretto or destination, and there was always as much in front as behind."

After the decline in popularity of The Bell, Herzen devoted his energies to My Past and Thoughts (1867). The book was a mixture of autobiography and an analysis of the social, political and ideological developments that had taken place during his life. Edward Acton has pointed out: "In its pages the pattern of his own life was skillfully woven into the fabric of political, social and ideological developments around him.... In fusing his personal experience with the history of an era, Herzen created a literary and political masterpiece which shows no signs of losing its force."

On this day in 1876 James Larkin, the son of Irish parents, was born in Liverpool. When he was five years old he was sent to live with his grandparents in Newry in Ireland.

Larkin returned to England in 1885 and found employment as a dock labourer. Converted to socialism, Larkin joined the Independent Labour Party in 1893 and spent his spare time selling The Clarion.

In 1893 Larkin became a foreman dock-porter for T. & J. Harrison Ltd. The following year he was sacked when he went on strike with his men. Larkin remained active in the union and in 1906 he was elected General Organizer of the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL).

Bertram D. Wolfe, who worked with Larkin, later recalled in his book, Strange Communists I Have Known (1966): "James Robert Larkin was a big-boned, large-framed man, broad shoulders held not too high nor too proudly, giving him an air of stooping over ordinary men when he was speaking to them. Bright blue eyes flashed from dark heavy brows; a long fleshy nose, hollowed out cheeks, prominent cheek bones, a long, thick neck, the cords of which stood out when he was angry, a powerful, stubborn chin, a head longer and a forehead higher than in most men, suggesting plenty of room for the brain pan. Big Jim was well over six feet tall, so that I, a six-footer, felt small when I looked up into his eyes. Long arms and legs, great hands like shovels, big, rounded shoes, shaped in front like the rear of a canal boat, completed the picture."

In January 1907 Larkin was sent by his union to Belfast and in his first three weeks recruited over 400 new members. The dock employers became concerned about this development and on 15th July 1907 decided to sack members of the NUDL. This action resulted in a long and bitter industrial dispute.

Larkin was now sent to Dublin to organize casual and unskilled workers in the docks. On 11th August 1907 Larkin formally launched the NUDL in the city. Over the next twelve months Larkin recruited 2,700 men to the union. He also led three strikes and the NUDL, concerned by the costs of these industrial disputes, suspended Larkin on 7th December 1908.

Larkin now established his own union, the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU). As well as Dublin the union had branches in Belfast, Derry and Drogheda. The ITGWU also had a political programme that included a "legal eight hours' day, provision of work for all unemployed, and pensions for all workers at 60 years of age. Compulsory Arbitration Courts, adult suffrage, nationalisation of canals, railways, and all the means of transport. The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland."

As well as organizing strikes he also became involved in the temperance campaign. According to one friend: "He neither drank nor smoked himself, engaging in a one man crusade against the drunkennes which was taken for granted among the rough, poor dockworkers over whom he acquired influence. No one ever heard foul language from his lips. He could be as hot tempered as any man, indeed hotter, but the temper expressed itself in withering repartee, angry condemnation, and scorn, sputtering, unforgettable epithets, never in obscenity."

James Larkin became a Christian Socialist: "There is no antagonism between the Cross and socialism! A man can pray to Jesus the Carpenter, and be a better socialist for it. Rightly understood, there is no conflict between the vision of Marx and the vision of Christ. I stand by the Cross and I stand by Karl Marx. Both Capital and the Bible are to me Holy Books."

His belief in industrial militancy upset the leaders of the Irish Trades Union Congress and he was expelled from the organization in 1909. In June 1910 Larkin was found guilty of misappropriating money while working for the NUDL and was sentenced to "one year's hard labour". One local newspaper complained that "Larkin was convicted by a packed jury which excluded Catholics and Nationalists." Many members of the union believed that Larkin had been convicted on false evidence and following a petition from the Dublin Trades Council he was released.

Larkin now established his own left-wing newspaper, The Irish Worker. In its first month, June, 1911, it sold 26,000 copies. In July it was 64,500, in August, 74,750, and in September, 94,994. Considering that Dublin only had a population of 300,000, these were impressive sales figures. It was a campaigning newspaper that named bad employers and corrupt government officials.

In 1912 Larkin joined with James Connolly in forming the Irish Labour Party. Later that year he won a seat on the Dublin Corporation. His success was short-lived as a month after the election he was removed on the grounds that a convicted felon had no right to be a member of the Corporation.

Constance Markievicz heard Larkin speak in 1913: "Sitting there, listening to Larkin, I realised that I was in the presence of something that I had never come across before, some great primeval force rather than a man. A tornado, a storm-driven wave, the rush into life of spring, and the blasting breath of autumn, all seemed to emanate from the power that spoke. It seemed as if his personality caught up, assimilated, and threw back to the vast crowd that surrounded him every emotion that swayed them, every pain and joy that they had ever felt made articulate and sanctified. Only the great elemental force that is in all crowds had passed into his nature for ever."

By 1913 the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union had 10,000 members and had secured wage increases for most of its members. Attempts to prevent workers from joining the ITGWU in 1913 led to a lock-out. When the police lined up to seek an excuse for breaking up one of his mass meetings he turned to his audience and said: "Look at them, well-dressed, well-fed! And who feeds them? You do! Who clothes them? You do! And yet they club you! And why? Because they are organized and disciplined and you are not!"

Larkin was arrested and sentenced to seven months in prison. Protest meetings in England led by James Keir Hardie, Ben Tillett, George Bernard Shaw, Robert Cunninghame Graham, Will Dyson and George Lansbury, resulted in Larkin being released.

However, some leaders of the Labour Party were opposed to Larkin's tactics of trying to encourage other union members to provide industrial support for the workers in Dublin. After railway workers in Liverpool, Birmingham, Derby, Sheffield and Leeds refused to handle traffic from Ireland, Larkin was denounced as the man responsible for introducing revolutionary syndicalism into Britain. In an article published in The Labour Leader, Philip Snowden wrote: "The Old Trade Unionism looked facts in the face, and acted with regard to commonsense. The new Trade Unionism, call it what you will - Syndicalism, Carsonism, Larkinism, does neither."

However, despite raising funds in England and the United States, Larkin's union eventually ran out of money and the men were gradually forced to return to work on their employer's terms. On 30th January 1914, Larkin admitted: "We are beaten, we will make no bones about it; but we are not too badly beaten still to fight."

On the outbreak of the First World War, Larkin called on Irishmen not to become involved in the conflict. In the Irish Worker he wrote: "Stop at home. Arm for Ireland. Fight for Ireland and no other land." He also organized large anti-war demonstrations in Dublin. Leaving James Connolly in charge of the ITGWU, Larkin left for a lecture tour of the United States in October 1914 in order to raise funds to help in the struggle for Irish Independence. In an interview in the New York Call, Larkin argued "that this war is only the outcome of capitalistic aggression, and the desire to capture home and foreign markets."

While in the USA Larkin joined the Socialist Party of America. A close friend of William Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Larkin also became involved in the activities of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In November 1915 Larkin joined other socialists in attending the funeral of Joe Haaglund Hill.

Larkin was influenced by the writings of Bouck White, especially his book, The Carpenter and the Rich Man (1914): Larkin told one audience: "I belong to the Catholic Church. I stand by the Cross and the Bible and I stand by Marx and his Manifesto. I believe in the creed of the Church, apostolic, Catholic, and Roman. I believe in its saints and its martyrs, their struggles and the sufferings of my people. The history of Ireland is full of the same spirit, the same struggles, the same sufferings, the struggles and sufferings of my people. In my land this is not held against a socialist. It speaks for him. I defy any man here or anywhere to challenge my standing as a Catholic, as a socialist, or as a revolutionist. We of the Irish Citizen's Army take communion before we ge into battle. We confess our sins. We seek absolution. If a bullet strikes, we hope to have the last rites administered to us before our souls leave our bodies. We do not let the Church stand in the way of our struggle, but neither do we let our struggle stand in the way of the Church."

Larkin also mourned the death of his friend, James Connolly, after the Easter Rising in 1916. On 17th March, 1918, Larkin established the James Connolly Socialist Club in New York City and it became the centre of left-wing activities among the Irish socialists in the city. One of the first people to speak at the club was John Reed, who gave a talk on the Russian Revolution.

Impressed with what he heard, Larkin joined the campaign led by Norman Thomas and Scott Nearing, to persuade the American government to recognize the new Soviet government. On 2nd February, 1919, Larkin spoke at a memorial meeting for the German left-wing leaders, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who had been executed following the Spartacist Rising in Berlin. Larkin upset a large number of people when he claimed that in 1919 "Russia is the only place where men and women can be free".

The right-wing leadership of the Socialist Party of America opposed the Russian Revolution. On 24th May 1919 the leadership expelled 20,000 members including Larkin. Some of these people, including Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Rose Pastor Stokes, Claude McKay, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, decided to form the American Communist Party. Larkin, concerned about a party that appeared to be under the control of a foreign government, refused to join. Larkin still supported the idea of parliamentary government and was critical of the tendency of its leaders to use "long words and abstract reasoning which went over the brows of the masses".

The support by radicals for the Russian Revolution worried Woodrow Wilson and his administration and America entered what became known as the Red Scare period. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the revolution, Alexander Mitchell Palmer, Wilson's attorney general, ordered the arrest of over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists. This included Larkin who was charged with "advocating force, violence and unlawful means to overthrow the Government".

Larkin's trial began on 30th January 1920. He decided to defend himself. He denied that he had advocated the overthrow of the Government. However, he admitted that he was part of the long American revolutionary tradition that included Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He also quoted Wendell Phillips in his defence: "Government exists to protect the rights of minorities. The loved and the rich need no protection - they have many friends and few enemies."

The jury found James Larkin guilty and on 3rd May 1920 he received a sentence of five to ten years in Sing Sing. In prison Larkin worked in the bootery, manufacturing and repairing shoes. Despite his inability to return to Ireland, he was annually re-elected as general secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union.

In November 1922, Alfred Smith won the election for Governor in New York. A few days later he ordered an investigation of the imprisonment of Larkin and on 17th January 1923 he granted him a free pardon. Larkin returned home to a triumphant reception. However, the new leader of the ITGWU, William O'Brien, was unwilling to step aside and managed to get Larkin expelled from the union in March 1924.

Larkin now established a new union, the Workers' Union of Ireland (WUI). He also became head of the Irish section of the Comintern and visited the Soviet Union in 1924. According to Bertram D. Wolfe he was not impressed with the communist system: "In 1924, the Moscow Soviet invited Larkin to come to its sessions as a representative of the people of Dublin, but he found nothing there to attract him, nor could they see their man in this wild-hearted rebel. I met him then, in the dining room of a Moscow hotel, where he was raising a series of scandals about the food, the service, and the obtuseness of waiters who could not understand plain English spoken with a thick Irish brogue... The Moscovites were glad when this eminent Dubliner returned to his native land."

Larkin successfully built up the WUI and in February 1932 won the North Dublin seat in the Dáil Éireann. However, he lost the seat in January 1933. Larkin was also forced to close down The Irish Worker. Later he started another radical newspaper, Irish Workers' Voice. He also served on the Dublin Trades Council, on the Port and Docks Board and the Dublin Corporation.

In the next election he won the North-East Dublin seat. However, in 1944 he was once again defeated at the polls. The following year his application to join the Irish Labour Party was finally accepted. James Larkin died in his sleep on 30th January, 1947. At his funeral Sean Casey said that Larkin had brought to the labour movement not only the loaf of bread but the flask of wine. Bertram D. Wolfe added: "James Larkin had outlived his time. He did not fit into the orderly, constructive, bureaucratized labour movement any more than he was suited to be a puppet of Moscow."

On this day in 1879, Helen Fraser, Helen Gwynne-Vaughan, the first leader of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) was born.

Helen Fraser was born into a Scottish aristocratic family in 1879. Educated at Cheltenham Ladies College her parents were shocked when she asked to study science at university. After obtaining a B.Sc. degree in Botany from King's College, London she carried out research into mycology.

In 1907 Fraser joined with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson to form the University of London Women's Suffrage Society. She also became a lecturer at Birkbeck College and eventually became Head of the Botany Department. In 1911 Helen married the palaeobotanist, Professor T. G. Gwynne-Vaughan.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Gwynne-Vaughan joined the Red Cross and became a VAD. This work was halted by the need to nurse her seriously ill husband. On the death of T. G. Gwynne-Vaughan in 1915, she returned to her voluntary war work.

In January 1917, the government announced the establishment of a new voluntary service, the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC). The plan was for these women to serve as clerks, telephonists, waitresses, cooks, and as instructors in the use of gas masks. It was decided that women would not be allowed to hold commissions and so that those in charge were given the ranks of controller and administrator. Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was chosen for the important job as the WAAC's Chief Controller (Overseas).

After a critical report of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) by Lady Margaret Rhondda, its commander, Violet Douglas-Pennant was dismissed. In September, 1918, Gwynne-Vaughan, who had gained a reputation as an efficient administrator in the WAAC, was asked by Sir William Weir, Secretary of State for Air, to take charge of the organization.

Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was a great success as commander of the Women's Royal Air Force. Sir Sefton Brancker argued that "the WRAF was the best disciplined and best turned-out women's organization in the country." Gwynne-Vaughan's work was recognised in June, 1919, when she was awarded the Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE). However, after the war it was decided to disband the WRAF and Gwynne-Vaughan left office in December, 1919.

Gwynne-Vaughan resumed her academic career and in 1922 published the well-received Fungi: Ascomycetes, Ustilaginales, Uredinales. Elected President of the British Mycological Society, she wrote a series of substantial papers in the 1920s and 1930s on the cytology of fungi.

Gwynne-Vaughan helped to form the WRAF Old Comrades Association and became its first president in March 1920. With war with Germany looking inevitable in the summer of 1939, Gwynne-Vaughan was asked to become head of the recently established Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). As she was now sixty she declined the offer and instead suggested Jane Trefusis-Forbes, the Director of the Auxiliary Territorial Services (ATS). However, she did agree to become Major-General of the ATS.

In 1941 Gwynne-Vaughan left the ATS and returned to Birkbeck College where she remained until her retirement in 1944.

Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was active in the Soldiers', Sailors' and Airmen's Families Association until just before her death in 1967.

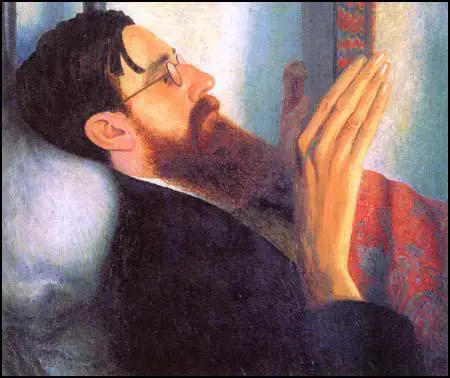

On this day in 1885 Duncan Grant, the only child of Major Bartle Grant and his wife, Ethel McNeil, was born in his family's ancestral home, The Doune, at Rothiemurchus, near Aviemore. His early years were spent in India and Burma, where his father's regiment was stationed.

In 1893 he returned to England for his schooling. At Rugby he met Rupert Brooke and developed an interest in art. After leaving school he went to live with his uncle, Richard Strachey (1817–1908). This brought him into contact with his children, Lytton Strachey, James Strachey, Oliver Strachey and Philippa Strachey.

Grant studied at the Westminster School of Art. As his biographer, Quentin Bell, pointed out: "On coming of age Grant used a £100 legacy from another aunt, Lady Colvile, to study for one year (1906–7) in Paris, at Jacques-Emile Blanche's La Palette. While there he copied Chardin in the Louvre and ignored, or remained unaware of, the controversy caused by the Fauves. Thus, though an art student in Paris during one of the most revolutionary moments in the history of painting, he continued, for some years yet, to paint with sober colours and formal restraint."

On his return to London, Duncan Grant had a brief affair with his cousin Lytton Strachey, before starting a long-term relationship with John Maynard Keynes. In 1905 Virginia Woolf and several friends and relatives began meeting to discuss literary and artistic issues. The friends, who eventually became known as the Bloomsbury Group, included Grant, Strachey, Maynard Keynes, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell, Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Virginia Woolf described him as being "a queer faun-like figure, hitching his clothes up, blinking his eyes, stumbling oddly over the long words in his sentences." He became a regular visitor to her Bloomsbury home. "How he lived I do not know. He was penniless. Uncle Trevor indeed said he was mad. He lived in a studio in Fitzroy Square with an old drunken charwoman called Filmer and a clergyman who frightened girls in the street by making faces at them. Duncan was on the best of terms with both. He was rigged out by his friends in clothes which seemed always to be falling to the floor. He borrowed old china from us to paint; and my father's old trousers to go to parties in.... He seemed to be vaguely tossing about in the breeze; but he always alighted exactly where he meant to."

In 1910 Grant's work was exhibited at the Grafton Galleries in London. This brought him to the attention of Edward Marsh, the wealthy art patron, who purchased his Parrot Tulips. Marsh later recalled that he decided to reject the advice of buying acknowledged masterpieces from the main Mayfair dealers. He said he found it much more exciting "to go to the studios and the little galleries, and purchase, wet from the brush, the possible masterpieces of the possible Masters of the future."

Grant helped Roger Fry, to select paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Artists included in the exhibition included Grant, Fry, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky.

Grant joined with Roger Fry and Vanessa Bell to form the Omega Workshops in 1913. According to his biographer, Quentin Bell: "While working closely together in the lead up towards the opening of the workshops, Grant and Bell moved into an intimate relationship which also marked the onset of an aesthetic partnership. Hitherto Grant's passions had been engaged almost always by members of his own sex and, although this essential aspect of his sexual nature never ceased to affect him, his union with Bell, and his friendship with her husband, played a determining role in the conduct of his life."

When the First World War was declared two pacifists, Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, formed the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." Grant joined the NCF. Other members included Bertrand Russell, Philip Snowden, Bruce Glasier, Robert Smillie, C. H. Norman, C. E. M. Joad, William Mellor, Arthur Ponsonby, Guy Aldred, Alfred Salter, Wilfred Wellock, Herbert Morrison, Maude Royden, Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, Catherine Marshall, Alice Wheeldon, John S. Clarke, Arthur McManus, Storm Jameson, Ada Salter, and Max Plowman.

Grant lived with Vanessa Bell and David Garnett at Wissett Lodge in Suffolk. Grant and Garnett worked on the farm as conscientious objectors but in 1916 a government committee on alternative service refused to let them continue there. They therefore moved to Charleston, near Firle, where they undertook farm work until the end of the war.

In 1918 Bell gave birth to Grant's child, Angelica Garnett. His biographer, Quentin Bell has argued: "Despite various homosexual allegiances in subsequent years, Grant's relationship with Vanessa Bell endured to the end; it became primarily a domestic and creative union, the two artists painting side by side, often in the same studio, admiring but also criticizing each other's efforts."

Dora Carrington was a regular visitor to Charleston. According to David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) she was shocked by the way they talked about Ottoline Morrell and Gilbert Cannan behind their backs. Carrington told Mark Gertler: "I think it's beastly of them to enjoy Ottoline's kindnesses and then laugh at her."

In 1935 Grant and Vanessa Bell accepted commissions to paint decorative panels for the new Cunard liner, RMS Queen Mary. However, unhappy with what he had produced, the work was rejected. They also provided the decorations in Berwick Church, that were completed in 1943.

During the Second World War he began an affair with the much younger Paul Roche. According to The Daily Telegraph: "One warm night in Piccadilly in 1946 Roche met the Bloomsbury post-impressionist painter Duncan Grant... Dressed up in a sailor suit as Roche was, Grant did not find out until years later about Roche's priestly secret.... Roche began to model for him on a regular basis and sometimes for Vanessa Bell." The relationship continued until Roche married and moved to the United States.

According to Margalit Fox: "Though observers over the years have described Mr. Roche and Mr. Grant as lovers, Ms. Roche de Aguiar said in a telephone interview that their relationship appeared to have been platonic. What is certain is that the two men shared a long, deep, loving friendship and that Mr. Grant was an early muse for Mr. Roche, encouraging him to write."

In the 1950s his reputation as an artist declined and he had difficulty selling his pictures except at very low prices. Frances Partridge pointed out: "Duncan Grant's charm was legendary. He never stopped painting, even during those years when his work was out of favour and his name unknown to the young; nor did it seem to affect him when fame returned to him. And he loved music. When he was well over eighty I invited him to the opera. Undeterred by having spent five mortal hours that day carefully studying an exhibition at the Tate, he arrived by Underground and on foot (not dreaming of taking a taxi), looking as usual remarkably like a tramp, with hair that seemed never to have known a brush, sat through the opera with unfaltering attention, and came back to supper afterwards with two much younger guests whom he easily outdid in animation."

Duncan Grant lived on his own at Charleston after the death of Vanessa Bell until the return of Paul Roche to England. In 1975 they took a house and spent six months in Tangier, where Paul nursed Grant through pneumonia.

Duncan Grant died bronchial pneumonia at the age of 93 at the home of Paul Roche in Aldermaston on 9th May 1978.

On this day in 1898 Thomas Ashton died at Ford Bank, Didsbury. Ashton was born in Hyde on 8th December, 1818. As a young man Thomas became a close friend of John Fielden, the owner of a large textile company in Todmorden. Ashton started a similar business in Hyde and eventually became one of Fielden's main competitors.

Ashton was a Unitarian and an active member of the Liberal Party, shared John Fielden's views on social reform. In 1870 Ashton worked closely with John's son, Samuel Fielden, in raising money for Owens College, the Nonconformist education establishment founded in Manchester by the cotton-merchant, John Owens. By 1870 Fielden and Ashton had raised £200,000 for the college.

As her biographer, Jane Bedford, has pointed out: "Not only did Thomas carry on the Ashton family tradition he had inherited as an employer - that of an employer who realized his responsibilities to the men and women who worked for him - he improved on it. He enlarged the mill school, built a church at Flowery Fields, and expanded the village built by his father; he also established scholarships at the Hyde Mechanics' Institute and the technical school which enabled students to go to Owens College and to the Manchester Technical School. Care of his employees had always been an important factor to him, and during the cotton famine, when many mills were closed and most employers ruined, Thomas Ashton made sure that his mills never stopped."

Ashton's daughter, Margaret Ashton, claims that "her father refused her request to be taken into the family business, although she was able to concern herself with its welfare policy." She was an active member of the Women's Liberal Federation, the Women's Trade Union League and the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies.

On this day in 1905 Father George Gapon sends a letter to Nicholas II. "The people believe in thee. They have made up their minds to gather at the Winter Palace tomorrow at 2 p.m. to lay their needs before thee. Do not fear anything. Stand tomorrow before the party and accept our humblest petition. I, the representative of the workingmen, and my comrades, guarantee the inviolability of thy person."

Father Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police".

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association."

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken."

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights."

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people.

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear."

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them.

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded.

Father George Gapon later described what happened in his book The Story of My Life (1905): "The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them. Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air."

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." It is not known the actual numbers killed on Bloody Sunday but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded.

Father Gapon escaped uninjured from the scene and sought refuge at the home of Maxim Gorky: "Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path."

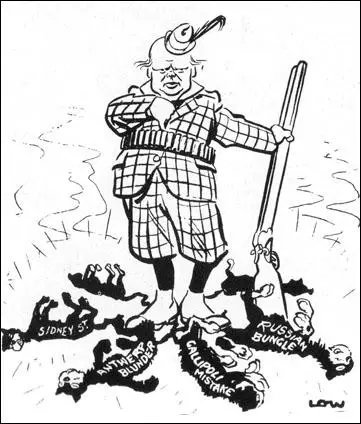

On this day in 1920 David Low published a cartoon in Evening Standard on Winston Churchill's foreign policy mistakes. Churchill blamed Jews for the Russian Revolution. He told Lord George Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, that in his opinion that the Bolsheviks had created a "tyrannical government of these Jew Commissars". In a letter to Frederick Smith he described them as "these Semitic conspirators" and "Semitic internationalists". In one speech he called the Russian government "a world wide communistic state under Jewish domination." At a public meeting in Sunderland he spoke of "the international Soviet of the Russian and Polish Jew."

In an article in the Illustrated Sunday Herald he argued: "The part played in the creation of Bolshevism and in the actual bringing about of the Russian Revolution by these international and for the most part atheistic Jews ... is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others. With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from Jewish leaders ... The same evil prominence was obtained by Jews in (Hungary and Germany, especially Bavaria)."

Churchill had supported the sending of British troops to help the White Army in the Russian Civil War, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward. However, it had not been a success Ward later told one of his officers, Brian Horrocks: "I believe we shall rue this business for many years. It is always unwise to intervene in the domestic affairs of any country. In my opinion the Reds are bound to win and our present policy will cause bitterness between us for a long time to come." Horrocks agreed: "How right he was: there are many people today who trace the present international impasse back to that fatal year of 1919."

Winston Churchill argued that the British had not sent enough troops. He argued in a Cabinet meeting that Britain should intervene "thoroughly, with large forces, abundantly supplied with mechanical appliances". He also suggested a campaign to recruit a volunteer army to fight in Russia. David Lloyd George admitted that the Cabinet was united in its hostility to the Bolsheviks but they did have support in Russia. He added that Britain had no right to interfere in their internal affairs and anyway lacked the means to do so.

Winston Churchill now took the controversial decision to use the stockpiles of M Device against the Red Army. He was supported in this by Sir Keith Price, the head of the chemical warfare, at Porton Down. He declared it to be the "right medicine for the Bolshevist" and the terrain would enable it to "drift along very nicely". Price agreed with Churchill that the use of chemical weapons would lead to a rapid collapse of the Bolshevik government in Russia: "I believe if you got home only once with the Gas you would find no more Bolshies this side of Vologda."

In the greatest secrecy, 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Archangel, along with the weaponry required to fire them. Winston Churchill sent a message to Major-General William Ironside: "Fullest use is now to be made of gas shell with your forces, or supplied by us to White Russian forces." He told Ironside that this "thermogenerator of arsenical dust that would penetrate all known types of protective mask". Churchill added that he would very much like the "Bolsheviks" to have it. Churchill also arranged for 10,000 respirators for the British troops and twenty-five specialist gas officers to use the equipment.

Some one leaked this information and Winston Churchill was forced to answer questions on the subject in the House of Commons on 29th May 1919. Churchill insisted that it was the Red Army who was using chemical warfare: "I do not understand why, if they use poison gas, they should object to having it used against them. It is a very right and proper thing to employ poison gas against them." His statement was untrue. There is no evidence of Bolshevik forces using gas against British troops and it was Churchill himself who had authorised its initial use some six weeks earlier.

On 27th August, 1919, British Airco DH.9 bombers dropped these gas bombs on the Russian village of Emtsa. According to one source: "Bolsheviks soldiers fled as the green gas spread. Those who could not escape, vomited blood before losing consciousness." Other villages targeted included Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. During this period 506 gas bombs were dropped on the Russians. Lieutenant Donald Grantham interviewed Bolshevik prisoners about these attacks. One man named Boctroff said the soldiers "did not know what the cloud was and ran into it and some were overpowered in the cloud and died there; the others staggered about for a short time and then fell down and died". Boctroff claimed that twenty-five of his comrades had been killed during the attack. Boctroff was able to avoid the main "gas cloud" but he was very ill for 24 hours and suffered from "giddiness in head, running from ears, bled from nose and cough with blood, eyes watered and difficulty in breathing."

Major-General William Ironside told David Lloyd George that he was convinced that even after these gas attacks his troops would not be able to advance very far. He also warned that the White Army had experienced a series of mutinies (there were some in the British forces too). Lloyd George agreed that Ironside should withdraw his troops. This was completed by October. The remaining chemical weapons were considered to be too dangerous to be sent back to Britain and therefore it was decided to dump them into the White Sea.

Winston Churchill created great controversy by the creation of Iraq. According to Boris Johnson: "He (Churchill) was the man who decided that there should be such a thing as the state of Iraq, if you wanted to blame anyone for the current implosion, then of course you might point the finger at George W. Bush and Tony Blair and Saddam Hussein - but if you wanted to grasp the essence of the problem of that wretched state, you would have to look at the role of Winston Churchill."

On this day in 1924 Lenin died of a heart attack. On 30th August, 1918, Lenin spoke at a meeting in Moscow. According to Victor Serge: "Lenin arrived alone; no one escorted him and no one formed a reception party. When he came out, workers surrounded him for a moment a few paces from his car." As he left the building Dora Kaplan, a member of the Socialist Revolutionaries, tried to ask Lenin some questions about the way he was running the country. Just before he got into his car Lenin turned to answer the woman. Serge then explained what happened next: "It was at this moment Kaplan fired at him, three times, wounding him seriously in the neck and shoulder. Lenin was driven back to the Kremlin by his chauffeur, and just had the strength to walk upstairs in silence to the second floor: then he fell in pain. There was great anxiety for him: the wound in the neck could have proved extremely serious; for a while it was thought that he was dying."

Two bullets entered his body and it was too dangerous to remove them. Kaplan was soon captured and explained that she had attempted to kill him because he had closed down the Constituent Assembly. In a statement to the police she confessed to trying to kill Lenin. "My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot at Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution. I was exiled to Akatui for participating in an assassination attempt against a Tsarist official in Kiev. I spent 11 years at hard labour. After the Revolution, I was freed. I favoured the Constituent Assembly and am still for it."

On 2nd September, as Lenin's life hung in the balance, Arthur Ransome, a British journalist, wrote an obituary hailing the founder of Bolshevism as "the greatest figure of the Russian Revolution". Here "for good or evil was a man who, at least for a moment, had his hand on the rudder of the world". He went on to say "common peasants who had known Lenin attested to his goodness, his extraordinary generosity to children. The workers looked up to him... not as an ordinary man, but as a saint". Without Lenin, Ransome concluded, the soviets would not perish, but they would lose their vital direction. "Fiery Trotsky, ingenious, brilliant Radek, are alike unable to replace the cool logic of the most colossal dreamer that Russia produced in our time."

Joseph Stalin, who was in Tsaritsyn at the time of the assassination attempt on Lenin, sent a telegram to Yakov Sverdlov suggesting: "having learned about the wicked attempt of capitalist hirelings on the life of the greatest revolutionary, the tested leader and teacher of the proletariat, Comrade Lenin, answer this base attack from ambush with the organization of open and systematic mass terror against the bourgeoisie and its agents."

Leon Trotsky agreed and argued in My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (1930): "The Socialist-Revolutionaries had killed Volodarsky and Uritzky, had wounded Lenin seriously, and had made two attempts to blow up my train. We could not treat this lightly. Although we did not regard it from the idealistic point of view of our enemies, we appreciated the role of the individual in history. We could not close our eyes to the danger that threatened the revolution if we were to allow our enemies to shoot down, one by one, the whole leading group of our party."

The Bolsheviks newspaper, Krasnaya Gazeta, reported on 1st September, 1918: "We will turn our hearts into steel, which we will temper in the fire of suffering and the blood of fighters for freedom. We will make our hearts cruel, hard, and immovable, so that no mercy will enter them, and so that they will not quiver at the sight of a sea of enemy blood. We will let loose the floodgates of that sea. Without mercy, without sparing, we will kill our enemies in scores of hundreds. Let them be thousands; let them drown themselves in their own blood. For the blood of Lenin and Uritsky, Zinovief and Volodarski, let there be floods of the blood of the bourgeois - more blood, as much as possible."