Women in Industrial Work

By 1910 women made up almost one third of the workforce. Work was often on a part-time or temporary basis. It was argued that if women had the vote Parliament would be forced to pass legislation that would protect women workers.

The Women's Industrial Council concentrated on acquiring information about the problem and by 1914 the organisation had investigated one hundred and seventeen trades. In 1915 Clementina Black and her fellow investigators published their book Married Women's Work. This information was then used to persuade Parliament to take action against the exploitation of women in the workplace.

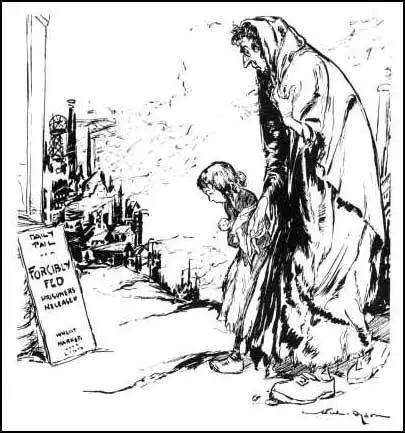

Will Dyson, The Daily Herald (1914)

Primary Sources

(1) In 1898 Selina Cooper wrote an article for a magazine entitled The Lancashire Factory Girl.

I have often heard the 'sarcastic' remark applied to the factory worker oh she is only a factory girl; thus giving the impression to the World that we have no right to aspire to any other society but our own. I am sorry to say that we are not fully awakened to the facts that we contribute largely to the nation's wealth, and therefore demand respect, and not insult. For in many a Lancashire home are to be found heroines whose names will never be handed down to posterity; yet it is consoling to know that we as a class contribute to the world.

(2) In 1906 Isabella Ford wrote a book, Women and Socialism, explaining why women suffragists should also be active in the socialist movement.

The Socialist movement, the Labour movement, call it which you will, and the Women's movement, are but different aspects of the same great force which has been, all through the ages, gradually pushing its way upwards, making for the reconstruction and regeneration of Society.

(3) In 1896 Isabella Ford wrote an article entitled Why I Joined the Independent Labour Party. One part of the article dealt with the subject of women and trade unions.

Some unions excluded women, and others admitted them, mostly in order to prevent them from being blacklegs to men. 'The women must be got in because they undersell us, they injure us' - it was the old story of Rousseau and the sole object of women's education being to make women useful to men, over again. I was thinking of leaving the Trade Union movement altogether for the antagonism between men and women was widening and I could see no way of interesting women in the movement. Women resent this spirit of antagonism between them and men.

(4) In 1893 Isabella Ford wrote a book called Women's Wages. The book includes a section on sexual harassment in factories.

A premium is sometimes put on impropriety of conduct on the women's part by the foreman. That is, a woman who will submit or respond to his course jokes and language and evil behaviour receives more work than the woman who feels and shows herself insulted by such conduct, and wishes to preserve her self respect. The pittance earned by some of these women is earned at the expense of more than only hard toil. Even when this coarseness is confined to language only, it causes deep suffering to some of the women. They feel, they know, that because they are women and therefore regarded as helpless and inferior, they are spoken to as men are not spoken to, and the sting enters their souls.

(5) In her booklet, Industrial Women and How to Help Them, written in 1901, Isabella Ford attempted to show why it was so important for industrial workers to get the vote.

Certainly trade unions will never flourish amongst women, until on election days the female union voice can make itself heard alongside the male union voice… It has always been so with men; and men and women are wonderfully alike… That the improved status a vote would give these women would be a large factor in raising their wages there cannot be the smallest doubt. In the language of the girls themselves about it. They don't dare put on a man same as they do on us; not they! 'Of course not,' said a male trade unionist, 'you see men have a vote.'

(6) On 22nd October 1907, Clementina Black spoke at the National Union Women Workers Conference about unskilled workers.

Trade unionism could not do for the unskilled trades and the sweated industries what it could do for other trades, and they must look to the law for protection. Surely the time was coming when the law, which was the representative of the organised will of the people, would declare that British workers should no longer work for less than they could live upon.

(7) Cicely Corbett Fisher, a representative of the Women's Industrial Council, gave a talk on sweated labour at East Grinstead in May 1912.

Sweated labour may be defined as (1) working long hours, (2) for low wages, (3) under insanitary conditions. Although its victims include men as well as women, women form the great majority of sweated workers. The chief difficulty is combating this evil abuse is that nearly all sweated work is done in the homes of the workers. During the recent strike of Jam makers in Bermondsey the wages of the girls only just sufficed to provide them with food, and left no margin whatsoever for the purchase of clothes, for which they were entirely dependent on gifts from friends… Chief among these evils of sweated labour is the exploitation of child labour. Children of six years and upwards were employed after school hours, in helping to add to the family output and even infants of 3, 4 and 5 years of age work anything from 3 to 6 hours a day in such labour as carding hooks and eyes to add a few pence per week to the wages of the household.

(8) In March, 1918, The East Grinstead Observer reported a speech made by Selina Cooper at the local branch of the Women's Citizen Association.

Selina Cooper explained that she started work when she was only ten years of age and for eighteen years was employed as a weaver. She said women needed to do on a collective basis what they could not do individually for themselves. As an industrial worker, and since as a wife and mother, she realised how much legislation concerned her… women had expert knowledge to enable them to deal with great reform. Take the housing problem, a woman was far more likely to detect anything lacking in a house than a man was. They needed women's idea of economy and her grasp of detail.