The Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain

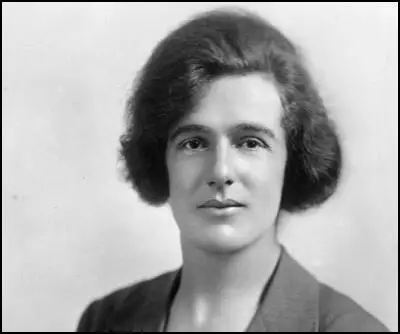

Kathlyn Oliver was a domestic worker: "She loathed this work, resenting not just the low wages and long hours but also how she was constantly watched over and treated like a machine." (1) Oliver moved jobs seven times before finding "a reasonable and fair employer". (2) Her life changed when she went to work for Mary Sheepshanks, principal of Morley College for Working Men and Women. Sheepshanks also was a leading speaker for the National Union of Suffrage Societies. (3) Sheepshanks, allowed Oliver to organize her own work so that she had some evenings free to attend classes at Morley College and pursue her political interests. (4)

Oliver began reading Woman Worker, a newspaper edited by Mary Macarthur, Secretary of the Women's Trade Union League. In 1909 Oliver joined a discussion already taking place in the correspondence pages of the newspaper, expressing her support for servants' demands for their own trade union. Macarthur encouraged her to organise such a trade union. In October 1909 she held a meeting to form a committee. Oliver made it clear that she wanted a union run by its members that would agitate for shorter hours and better food and accommodation for live-in servants, enforced by government legislation. (5)

Kathlyn Oliver claims that she was "besieged on all sides with letters from servants requiring information". (6) The Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain (DWUGB) was officially launched in the spring of 1910, admitting both men and women members. Kathlyn Oliver remained in charge of funds, but passed her acting role of general secretary over to Grace Neal, a domestic cook. Its head office was at 211 Belsize Road, London. (7)

An anonymous contributor to The Common Cause pointed out the problems of domestic servants: "In a fairly good place she (the domestic servant) has to get up not later than seven, and from that hour she is at the command of her mistress until ten o'clock at night, all the week through from Monday morning until Sunday night. When we average our time off one week with another it only averages eight hours a week, eleven one week and five the other, and should the lady be entertaining (which she often is) we are expected to give it up willingly, and if we did not, we should be marked as not obliging. Undoubtedly the domestic servant has many grievances, and the greatest of all is excessive hours of labour and too little time for recreation and self-culture." (8)

According to Grace Neal by January 1911 Oliver had left the DWUGB and was now concentrating on the campaign for women's suffrage: "Miss Kathlyn Oliver is the late secretary of the Domestic Servants' Union and she makes a striking appeal for the domestic servants' admission to the electorate. She submits that workers who do not possess the vote are beyond the ken and interest of Parliament. She predicts that when domestic workers have the vote they will be regarded, with respect, and that when they are regarded with respect, "the conditions of the labour will speedily improve". We are not sure that we agree with Miss Oliver that the mere occasion of a vote to domestic servants will necessary or even probably improve their conditions. She admits that the living-in system makes the organisation of servants practically impossible, and it seems to us the difficulty of organisation must be overcome before the vote can become an effective instrument for bettering their conditions. We would not oppose the granting of a vote to domestic servants, but we quail before the prospect of greasy canvassers pushing their political wares under the bewildered eyes of cook and parlour-maid at the tradesman door. We see no immediate solution of the difficulty, but we are quite sure that domestic service is radically wrong. And we are unable to see that the vote would help matters." (9)

Kathlyn Oliver became critical of domestic servants who had refused to join the union. As she explained in The Common Cause. "I was disappointed to see in this discussion on Domestic Service that so many of the correspondence refuse to give their names; but, though I do not like to say so, it is typical of the whole class. As I mentioned in a previous letter, I am a domestic myself and am as dissatisfied with the general conditions of domestic service as anyone, but, unlike the average domestic, I do not keep my opinions on the subject a secret. My experience in domestic service has been wide rather than long, and for the last five years I have been in constant touch and association with domestics as one of themselves, and their attitude on this subject has infuriated and disgusted me. I feel that if they would give up their petty backbiting of their employers and the secret grumbling and complaining, and openly and honestly voice their grievances some, if not all, of the objectives would vanish." (10)

Oliver put most of the blame on the employers: "As a domestic servant, it is with regret that I endorse the opinion of your correspondent, a 'Well-known Sheffield Resident', that the average domestic servant is mean, underhand, and possess little, if any, sense of honour. But these deplorable characteristics in domestic servants are the inevitable effect of a cause. Mistresses themselves are entirely responsible. The average employer of domestic labour regards this work as one of the lowest and meanest order, and domestic workers as menials and as infinitely their inferiors. Surely it is a little illogical to expect our 'inferiors' to act as our equals in sense of honour, etc. In spite of the heroic efforts which many of my previous employers have made to convince me that I was their inferior because I performed domestic work they never succeeded. I am a domestic, and, incredible as it may appear. I have a sense of honour, and I scorn mean, underhand dealings, not necessarily because I respect my employer (I had the same feelings when I worked for those whom I despised), because I respect myself." (11)

By January 1913 the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain had acquired a regular subscribing membership of about 400 domestic servants. (12) This is not a large number as it is estimated that at this time nearly 1.3 million women across the United Kingdom worked as domestic servants (housemaids, cooks, scullery maids, etc.). (13)

Kathlyn Oliver argued in one pamphlet that the living-in system should be abolished in favour of the state-employment or ‘nationalization' of domestic workers. (14) In 1913 the Domestic Workers' Union joined forces with the Scottish Federation of Domestic Workers founded by Glasgow-based domestic servant Jessie Stephen. A member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) Stephen had started organizing maidservants in Glasgow into a domestic workers' union branch in 1912. She moved to London to work for the Domestic Workers' Union. Stephen was an active member of the Women Social & Political Union and helped to develop close links with both organisations. (15)

On 28th January 1913, Margaret Macfarlane took part in an attempt to discuss women's suffrage with David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Organised by Flora Drummond and Sylvia Pankhurst, Macfarlane was apparently representing the demands of the Domestic Workers' Union. As Votes for Women explained: "Mrs Drummond led a deputation of working women from the Horticultural Hall to demand a further interview at the House of Commons with the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The interview was refused, and the women were treated with violence by the police. Mrs Drummond herself was knocked down and injured shortly after her emergence from the hall. Persisting, however, in her mission, she and a number of other women, including Miss Sylvia Pankhurst were taken into custody... Of the window-breakers. Miss Mary Neil was fined and ordered to pay the damage, or in default fourteen days; Miss Margaret Macfarlane was similarly dealt with, or in default fourteen days." (16)

On 20th March 1913, Margaret Macfarlane was arrested again and charged with breaking two windows at the Tecla Gem Company, Ltd, Old Bond Street, Macfarlane sentenced to five months in the second division. (17) The Suffragette reported that the Domestic Workers' Union held protest meetings about this sentence: "At a meeting organised by the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain in Trafalgar Square on Sunday, a resolution was unanimously carried, protesting against the sentence of five months imprisonment passed on Miss Margaret Macfarlane for her actions on behalf of domestic servants, and calling upon the government to release her immediately." (18)

Kathlyn Oliver was a self-proclaimed feminist who supported women's suffrage and was a member of the People's Suffrage Federation. Yet her advocacy of domestic servants' rights often led to clashes with the leaders of the National Union of Suffrage Societies and Women Social & Political Union. "She was quick to point out the hypocrisy of middle-class women who claimed to be working for the emancipation of their sex while exploiting their female servants. She insisted that the Domestic Workers' Union was there to represent the interests of the workers, rather than depend upon the goodwill of a handful of enlightened mistresses, and she did not attempt to deny accusations of advocating ‘class war' between women." (19)

Although the leader of a trade union and critical of the middle-class nature of the women's suffrage organisations, Oliver realised that the servants' self-organization alone was enough to bring about the changes she desired, and she now preferred to "advocate the parliamentary vote as the best means of improving the conditions of domestic labour". (20)

The outbreak of the First World War brought an end to the Domestic Workers' Union as many of its members left service for better-paid work in factories and munitions. (21)

Note: The Domestic Workers' Union is covered in some detail in chapter 5 of Laura Schwartz's Feminism and the Servant Problem (2019)

Primary Sources

(1) The Suffragette (25th April 1913)

At a meeting organised by the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain in Trafalgar Square on Sunday, a resolution was unanimously carried, protesting against the sentence of five months imprisonment passed on Miss Margaret Macfarlane for her actions on behalf of domestic servants, and calling upon the government to release her immediately. Miss Macfarlane was sentenced on March 20, and her protest took the form of breaking windows in Bond Street.

(2) Grace Neal, Labour Leader (13th January 1911)

Miss Kathlyn Oliver is the late secretary of the Domestic Servants' Union and she makes a striking appeal for the domestic servants' admission to the electorate. She submits that workers who do not possess the vote are beyond the ken and interest of Parliament. She predicts that when domestic workers have the vote they will be regarded, with respect, and that when they are regarded with respect, "the conditions of the labour will speedily improve". We are not sure that we agree with Miss Oliver that the mere occasion of a vote to domestic servants will necessary or even probably improve their conditions. She admits that the living-in system makes the organisation of servants practically impossible, and it seems to us the difficulty of organisation must be overcome before the vote can become an effective instrument for bettering their conditions. We would not oppose the granting of a vote to domestic servants, but we quail before the prospect of greasy canvassers pushing their political wares under the bewildered eyes of cook and parlour-maid at the tradesman door. We see no immediate solution of the difficulty, but we are quite sure that "domestic service" is radically wrong. And we are unable to see that the vote would help matters.

(3) Kathlyn Oliver, The Common Cause (23rd November 1911)

I was disappointed to see in this discussion on Domestic Service that so many of the correspondence refuse to give their names; but, though I do not like to say so, it is typical of the whole class. As I mentioned in a previous letter, I am a domestic myself and am as dissatisfied with the general conditions of domestic service as anyone, but, unlike the average domestic, I do not keep my opinions on the subject a secret.

My experience in domestic service has been wide rather than long, and for the last five years I have been in constant touch and association with domestics as one of themselves, and their attitude on this subject has infuriated and disgusted me. I feel that if they would give up their petty backbiting of their employers and the secret grumbling and complaining, and openly and honestly voice their grievances some, if not all, of the objectives would vanish.

I think there can be little doubt that the entire system of domestic service needs revolutionising, or rather, nationalising. I know that few will agree, but I feel that on the present basis, with the present ideas, domestic work can never be entirely satisfactory, except perhaps for a few.

One feels that Upton Sinclair, in his wonderful book The Jungle, does not write too strongly against domestic work in its private capacity when he describes it as deadening and brutalising work, and ascribes to it anaemia, nervousness, ugliness and ill-temper, prostitution, suicide and insanity.

The ideas which now make it possible for an employer to talk about allowing her domestic so much (or so little) freedom must be swept away, as well as the ideas which cause some employers to expect servility and bowing and scraping, in return for certain wages.

(4) Kathlyn Oliver, The Evening Standard (23rd November 1911)

As a domestic servant, it is with regret that I endorse the opinion of your correspondent, a "Well-known Sheffield Resident", that the average domestic servant is mean, underhand, and possess little, if any, sense of honour. But these deplorable characteristics in domestic servants are the inevitable effect of a cause. Mistresses themselves are entirely responsible. The average employer of domestic labour regards this work as one of the lowest and meanest order, and domestic workers as menials and as infinitely their inferiors. Surely it is a little illogical to expect our "inferiors" to act as our equals in sense of honour, etc. In spite of the heroic efforts which many of my previous employers have made to convince me that I was their inferior because I performed domestic work they never succeeded. I am a domestic, and, incredible as it may appear. I have a sense of honour, and I scorn mean, underhand dealings, not necessarily because I respect my employer (I had the same feelings when I worked for those whom I despised), because I respect myself.

Will employers never learn that they cannot have servility and straightforward, honourable dealing at the same time? The two are absolutely incompatible. If they desire the former it must be rendered at the cost of the latter and vice versa. (22 Calais Gate, Camberwell, SE)

(5) Letter signed "One in Five", The Common Cause (23rd November 1911)

I read the letter on Domestic Service in the issue of The Common Cause, November 2, and being a domestic servant, I was particularly interested in it. I notice she tells us some ladies have said they allow their maids to go to bed at ten o'clock and one evening out a week, also alternate Sundays. Well, granted that is true, as it is in my experience, let us see what this means to the servant.

In a fairly good place she has to get up not later than seven, and from that hour she is at the command of her mistress until ten o'clock at night, all the week through from Monday morning until Sunday night.

When we average our time off one week with another it only averages eight hours a week, eleven one week and five the other, and should the lady be entertaining (which she often is) we are expected to give it up willingly, and if we did not, we should be marked as not obliging.

Undoubtedly the domestic servant has many grievances, and the greatest of all is excessive hours of labour and too little time for recreation and self-culture.

However, there is a ray of light at last in the 18 months old organisation known as the Domestic Workers' Union of Great Britain. And although the task of combination is a difficult one on account of the fact that we work in ones, twos, threes, fours and fives and not in fifties and hundreds as the mill workers do, we nevertheless feel strong in our awakening strength, and let us all pull together in order that our Union may fulfil its mission.

(6) Laura Schwartz, Kathlyn Oliver: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (9th April 2020)

In 1909 Kathlyn Oliver joined a discussion already taking place in the correspondence pages of the Woman Worker newspaper, expressing her support for servants' demands for their own trade union. The paper's editors responded to Oliver directly, asking if she would take it upon herself to initiate such a union. More servants wrote in favour of this idea, but the offer had to be put to Oliver again until a full month later she agreed, calling a first meeting in October 1909 to form a committee. Oliver intended that the union should not simply provide out-of-work benefits for its members along the lines of a friendly society, nor was it a top-down philanthropic organization. Instead she envisaged a militant union run by its members that would agitate for shorter hours and better food and accommodation for live-in servants, enforced by government legislation.