On this day on 20th January

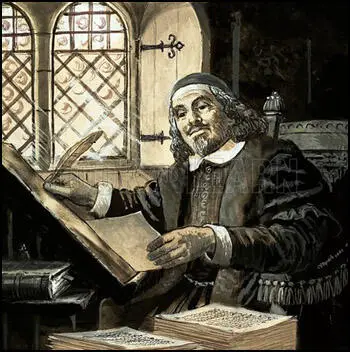

On this day in 1569 Bible translator, Miles Coverdale died. Coverdale was born in Yorkshire in 1488. Little is known of his early life and the first time he appears in the official record is when he became an ordained priest in Norwich in 1514. Coverdale became an Augustinian friar in Cambridge.

During this period he met Robert Barnes who "became prior of the Austin friars there and initiated a series of reforms which centred on the introduction into the curriculum of such classical Latin authors as Terence, Plautus, and Cicero, and the replacement of scholastic authors with a course on the letters of St Paul."

According to John Foxe through his reading, discussions, and preaching. Barnes became famous for his knowledge of scripture, always preaching against bishops and hypocrites, yet he continued to support the church's idolatry until he was converted by Thomas Bilney to the ideas of Martin Luther.

Robert Barnes had a tremendous influence on Coverdale. John Bale later recalled: "Under the mastership of Robert Barnes he drank in good learning with a burning thirst. He was a young man of friendly and upright nature and very gentle spirit, and when the church of England revived, he was one of the first to make a pure profession of Christ … he gave himself wholly, to propagating the truth of Jesus Christ's gospel and manifesting his glory… The spirit of God … is in some a vehement wind, overturning mountains and rocks, but in him it is a still small voice comforting wavering hearts. His style is charming and gentle, flowing limpidly along: it moves and instructs and delights.

On 24th December 1525, Barnes preached a sermon in St Edward's Church, in which he attacked the corruption of the clergy in general and that of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in particular. He was arrested on 5th February 1526. Miles Coverdale helped him prepare his defence. Barnes was taken to London where he appeared before Wolsey and was found guilty. He was made to do public penance by carrying a faggot (a bundle of sticks bound together as fuel) on his back to Paul's Cross. The faggot was a symbol of the flames around the stake. Barnes was sent to Fleet Prison.

It is believed that Coverdale first met Thomas Cromwell in 1527. The following year he left the Augustinians and "going in the habit of a secular priest" and according to David Daniell he "preached in Essex against transubstantiation, the worship of images, and confession to the ear." These were dangerous views and towards the end of 1528 he fled to Antwerp.

In 1528 Robert Barnes was moved to the Austin House in Northampton, where he was kept under close guard. Robert Barnes now staged an elaborate escape to rid himself of the unwanted attention from the authorities. Leaving a suicide note for Wolsey, a pile of clothes on the river-bank, and a letter to the mayor of Northampton, asking him to search the river. Although they did not find a body it was reported all over Europe that Barnes had killed himself." Barnes disguised himself as a pauper and fled to London. He then sailed to Antwerp where he joined up with Miles Coverdale, William Tyndale and John Frith.

The continued export of Tyndale's Bibles into England upset conservatives such as Lord Chancellor Thomas More who insisted that anyone who read and distributed the Bible should suffer a "painful death". In 1530 Henry VIII gave orders that all English Bibles were to be destroyed. People caught distributing the Tyndale Bible in England were burnt at the stake. This attempt to destroy Tyndale's Bible was very successful as only two copies have survived.

Lacey Baldwin Smith accused William Tyndale of sharing More's paranoia: "More and his chief polemical rival, William Tyndale, did not hesitate to indulge in paranoid hyperbole. A conspiratorial approach to human affairs was just as central to Tyndale's thinking as it was to More's... Catholic or Protestant, conservative or reformer, each side depicted the opposition as a small band of evil men and women dressed in the cloak of conspiracy and carrying the dagger of sedition."

William Tyndale was visited secretly in 1531 by Thomas Cromwell's emissary, Stephen Vaughan, who invited him to return to England. "One evening in April 1531 Vaughan met Tyndale in a field outside Antwerp, and afterward wrote to Cromwell a long account of their conversation. Tyndale declared his strong loyalty to the king: he lived in constant poverty and danger to bring the New Testament to the king's subjects. Did the king, Tyndale asked, fear those subjects more than the clergy? Vaughan met Tyndale again in May. Tyndale movingly sent his promise that if the king would grant his people a bare text (of the scriptures, in their language), as even the emperor and other Christian princes had done, whoever made it, then he would write no more and submit himself at the feet of his royal majesty. A third meeting had the same result. Vaughan wrote twice again to Cromwell on Tyndale's behalf, with no effect."

Tyndale feared that he would be arrested if he returned to England. He told Vaughan that he would definitely not be returning while Sir Thomas More was in power. Another reason Tyndale did not return was that he was aware that it would not be long before he was in conflict with the King over the issue of his desire to divorce Catherine of Aragon. Tyndale told Vaughan that he could "not in conscience promote Henry's matrimonial cause".

Lord Chancellor More sent a close friend, Sir Thomas Elyot, to try to arrange the arrest of Tyndale. This ended in failure and the next person to try was Henry Phillips. He had gambled away money entrusted to him by his father to give to someone in London, and had fled abroad. Phillips offered his services to help capture Tyndale. After befriending Tyndale he led him into a trap on 21st May, 1535. Tyndale was taken at once to Pierre Dufief, the Procurer-General, who immediately raided Poyntz's house and took away all Tyndale's property, including his books and papers. Luckily, his work on the Old Testament was being kept by John Rogers. Tyndale was taken to Vilvorde Castle, outside Brussels, where he was kept for the next sixteen months.

At the time of his arrest, William Tyndale had translated the Old Testament only as far as the Book of Chronicles. Miles Coverdale continued with his work and his translation of the entire Bible in English was completed on 4th October 1535. It included sixty-seven woodcut illustrations. The title-page of the first printing, included a picture of King Henry VIII distributing bibles. Coverdale explains that he has "with a clear conscience purely and faithfully translated this out of five sundry interpreters". He did not mention that it was largely based on the work of Tyndale.

While the Bible was being printed, William Tyndale was being tried by seventeen commissioners, led by three chief accusers. At their head was the greatest heresy-hunter in Europe, Jacobus Latomus, from the new Catholic University of Louvain, a long-time opponent of Erasmus as well as of Martin Luther. Tyndale conducted his own defence. He was found guilty but he was not burnt alive, as a mark of his distinction as a scholar, on 6th October, 1536, he was strangled first, and then his body was burnt. John Foxe reports that his last words were "Lord, open the king of England's eyes!"

William Tyndale's main enemy, Sir Thomas More, had been executed on 6th July, 1535. Miles Coverdale felt safe enough to return to England. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, were now the key political figures in England. They wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic and ordered to be burnt at the stake by Henry VIII eleven years before, for producing such a Bible. The edition they promoted, although mainly the work of Tyndale, had the name of Miles Coverdale on the cover. Cranmer approved the Coverdale version on 4th August 1538, and asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England.

Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September, 1538. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Coverdale Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm."

The arrest and execution of Thomas Cromwell and Robert Barnes in 1540 brought an end to reform and Bishop Stephen Gardiner became the King's major religious adviser. Miles Coverdale now decided to return to the safety of Europe. Coverdale and his wife (Elizabeth Macheson) went to live in Strasbourg. Over the next few years he translated several religious books from Latin and German and wrote an important defence of his martyred friend Barnes. In September 1543 Coverdale became assistant minister of Bergzabern and headmaster of the town school, posts he held for five years.

In January 1547 Edward VI came to the throne and the following year Miles Coverdale returned to London. He became almoner to Catherine Parr who since the death of Henry VIII had married Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who had been appointed Lord Protector. Catherine gave birth to a daughter named Mary on 30th August 1548. After the birth, Catherine developed puerperal fever. Her delirium took a painful form of paranoid ravings about her husband and others around her. Catherine accused the people around her of standing "laughing at my grief". She told the women attending her that her husband did not love her. Thomas Seymour held her hand and replied "sweetheart, I would do you no hurt". Seymour is reported to have lain down beside her, but Catherine asked him to leave because she wanted to have a proper talk with the physician who attended her delivery, but dared not for fear of displeasing him.

The fever eventually went and she was able to dictate her will calmly, revealing that Thomas Seymour was the "great love of her life". Queen Catherine, "sick of body but of good mind", left everything to Seymour, only wishing her possessions "to be a thousand times more in value" than they were. Catherine, thirty-six years old, died on 5th September 1548, six days after the birth of her daughter. (21) Coverdale preached the sermon at her funeral in September 1548 at Sudeley Castle in Gloucestershire. The following month Archbishop Thomas Cranmer arranged for him to become royal chaplain. Coverdale preached at Paul's Cross on the second Sunday in Lent 1549, again on Low Sunday, and again on Whit Monday.

Miles Coverdale was an opponent of Anabaptism and did not protest against the burning of Joan Bocher was burnt at Smithfield on 2nd May 1550. "She died still upbraiding those attempting to convert her, and maintaining that just as in time they had come to her views on the sacrament of the altar, so they would see she had been right about the person of Christ. She also asserted that there were a thousand Anabaptists living in the diocese of London."

Coverdale a member of the commission appointed in January 1551 to deal with Anabaptism and other heresy. He sat as judge alongside Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Nicholas Ridley at the trial of George van Parris, a Flemish Anabaptist denounced for Arian views: he knew no English, so Coverdale acted as interpreter. He was examined on his views, and most especially the belief that "God the Father is only God, and that Christ is not very God". His refusal to recant sealed his fate, and he was condemned for Arianism on 7th April. Parris was burnt alive on 25th April 1551.

On 30th August 1551, Miles Coverdale was appointed Bishop of Exeter. It was reported that "Coverdale preached continually upon every holy day, and did read most commonly twice in the week in some one church or other within this city. He was, after the rate of his livings, a great keeper of hospitality, very sober in diet, godly in life, friendly to the godly, liberal to the poor, and courteous to all men, void of pride, full of humility, abhorring covetousness, and an enemy to all wickedness and wicked men". However, he was unpopular with Catholics and it was claimed that there were attempts to poison him.

King Edward VI died on 6th July 1553. It was not long before Coverdale found himself summoned to appear before the Privy Council. Queen Mary purged the Church hierarchy of Protestants. Coverdale was imprisoned and some of his closest friends, John Rogers, Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burnt at the stake. Coverdale was also in danger that the same thing would happen to him but he was helped by his case being taken up by King Christian III of Denmark. Queen Mary eventually agreed that Coverdale should be released in February, 1555, and allowed "to pass from hence towards Denmark with two of his servants, his bags and baggages".

The Coverdale family only spent a short time in Copenhagen before moving on to Frankfurt. In August 1557 Coverdale, his wife and two children, settled in Switzerland, arriving at Aarau on 11th August 1557. A little over a year later, on 24th October 1558, he was given permission to live in Geneva. During this period he worked with others on what became known as the Geneva Bible.

Miles Coverdale returned to England after the death of Queen Mary. Now aged seventy-two he rejected the offer of taking up his old position as Bishop of Exeter. He did attend the consecration of Archbishop Matthew Parker in the chapel of Lambeth Palace on 17th December 1559. After the death of his wife, Elizabeth Coverdale, in September 1565, he married his second wife, Katherine, on 7th April 1566.

On this day in 1790 John Howard died. Howard, the son of a successful businessman, was born in Hackney, London, on 2nd September, 1726. His mother died soon after his birth and so John was sent away to boarding school in Hertford.

When he was sixteen John Howard's father died leaving him enough money to live a life of leisure. Howard spent his time travelling around the world. In 1756 the ship he was on was captured by the French. After spending time in a French prison, Howard was eventually released. Howard was shocked by the condition of dungeon in which he was imprisoned and when he arrived back in England he sent a report to the authorities detailing the sufferings of his fellow prisoners.

On 25th April 1758 John Howard married Henrietta Leeds. The marriage was successful and over the next couple of years Howard spent his time erecting high-quality cottages for his estate workers and their families. Howard was devastated when his wife died giving birth to their first child in 1765.

John Howard di returned to travelling the world but while in Naples in 1770 he had a religious experience which resulted in him making a promise to God that he would do whatever was required of him. Howard now became a devout Congregationalist. As a result of the Test Act passed in 1673, Howard was not allowed to hold civil or military office. However, when he was invited in February 1773, to become High Sheriff of Bedford, he accepted the post as he saw it as a way to serve God.

One of Howard's responsibilities as High Sheriff was to inspect the county prison. He was appalled by what he found at Bedford Gaol. At first Howard believed that the suffering of the prisoners was largely being caused by the system where the gaoler received money from the prisoner for his board and lodging. Howard suggested to Bedford justices that the gaoler should be paid a salary. The justices were unwilling to increase the cost of looking after prisoners and replied that the whole country used the same system.

Howard decided to carry out a tour of neighbouring prisons to see if this was the case. He discovered that all the prisons he visited were as bad if not worse that Bedford Gaol. Over the next three years travelled over 10,000 miles collecting information about the conditions in prisons. On 4th March 1774 he gave some of the evidence that he had collected to the House of Commons.

As a result of the testimony that John Howard provided, Parliament passed the 1774 Gaol Act. The terms of this legislation abolished gaolers' fees and suggested ways for improving the sanitary state of prisons and the better preservation of the health of the prisoners. Although Howard had copies of these acts printed and sent to every prison in England, the justices and the gaolers tended to ignore these new measures.

In 1775 Howard began a tour of foreign prisons. Over the next few years he visited prisons in France, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Russia, Switzerland, Malta, Asia Minor and Turkey. Although most of these prisons were as bad as those in England, Howard did find one that was far superior, Maison de Force in Ghent. He now used Maison de Force as an example of what other British prisons should be like. When Howard returned to England he began a second tour of its prisons to see if the reforms of the 1774 Gaol Act were being implemented.

In 1777 Howard published the result of his investigations, The State of Prisons in England and Wales, with an Account of some Foreign Prisons. The contents of Howard's book was so shocking that in some countries, such as France, the authorities refused to allow it to be published. Howard continued to inspect prisons and in March 1787 he completed his fourth tour of those in England. This was followed by the publication of An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe and Additional Remarks on the Present State of Prisons in Great Britain and Ireland.

In 1789 John Howard set out once again to tour foreign prisons. He visited Holland and Germany and by December was in Russia. John Howard contracted typhus while visiting a military Russian hospital at Kherston and died on 20th January, 1790.

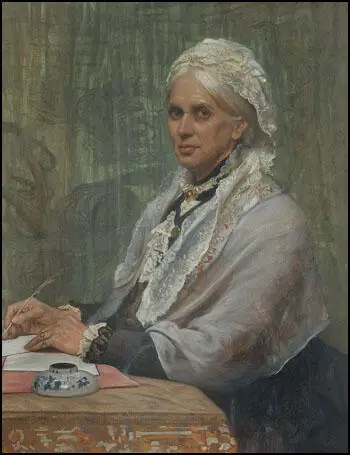

On this day in 1820 Anne Jemima Clough, the daughter of James Clough and Anne Perfect, was born in Liverpool. Two years later the family moved to Charleston in South Carolina.

In 1836 the family returned to Liverpool where James Clough became a cotton merchant. The three sons were sent to private schools but Anne was educated at home by her mother. Anne was particularly close to her brother Arthur Hugh Clough. Arthur, had been taught by Thomas Arnold at Rugby and won a scholarship to Balliol College, Cambridge. Arthur, who was later to become professor of English Literature at University College, London, took a keen interest in Anne's education. He directed her studies and under his influence she began to visit and teach the poor.

After James Clough's business failed in 1841, Anne opened a small school in Liverpool to help pay off the family debts. The school opened in January 1842 but it attracted few children. Anne had doubts about her abilities as a teacher and in May 1843, wrote in her journal: "I fear I mismanage the children; however, I must try to do better."

In 1852 Anne moved to the village of Ambleside where she opened a school for the children of local farmers and trades people. Anne's school was popular and she soon had enough children to employ two other teachers.

Devastated by the death of her brother, Arthur Hugh Clough, Anne gave up the running of her school. However, Anne's achievements in Ambleside were well-known and in 1864 she was contacted by Emily Davies who was involved in the campaign to improve the quality of women's education. Encouraged by Davies, Clough wrote an article, Hints on the Organization of Girls' Schools for Macmillan's Magazine.

In 1865 Anne Jemima Clough joined Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Garrett at meetings of the Kensington Society. After the failure of Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill in 1867 to persuade Parliament to give women the same political rights as men, the women formed the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

Inspired by the success of the North London Collegiate School and Cheltenham Ladies College, Clough decided to form the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women. The council held its first meeting at Leeds in 1867 and members included Josephine Butler, George Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme. Over the next few years the council developed a scheme of lectures and a university-based examination for women who wished to become teachers.

In 1871, Henry Sidgwick, who taught at Trinity College, established Newnham, a residence for women who were attending lectures at Cambridge University. Anne was invited to take charge and by 1879 Newnham College was fully established with its own tutorial staff.

As well as being principal of Newnham College, Clough helped to establish the University Association of Assistant Mistresses (1882), the Cambridge Training College for Women (1885), and the Women's University Settlement in Southwark (1887).

Anne Clough died on 27th February 1892.

On this day in 1884 Yevgeni Zamyatin, was born in Lebedyan, Russia. The son of a teacher, Zamyatin trained as a naval engineer at St Petersburg. While a student joined the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). He later wrote: "To be a Bolshevik in those years meant following the path of greatest resistance, so I was a Bolshevik then."

Zamyatin's support of the Bolsheviks resulted in him being arrested and sent into exile. He returned during the 1905 Revolution and joined the student demonstrations against Nicholas II. Zamyatin was arrested, badly beaten and sent to Spalernaja Prison where he had to endure several months of solitary confinement.

After graduating Zamyatin became a lecturer at the Department of Naval Architecture. He wrote several articles on ship construction for journals such as The Ship and Russian Navigation. He also wrote fiction and in 1913 published the novel A Provincial Tale. This was followed by At The World's End (1914), a satire on military life. This upset the censors and Zamyatin was brought to trial but was acquitted. However, the book was banned and all copies were destroyed.

During the First World War Zamyatin was sent to England to supervise the building of Russian icebreakers. He returned to Russia after the October Revolution. Although initially a supporter of the Bolsheviks he began to question the new government's attempt to control the arts.

Zamyatin switched his support to the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and published a series of political fables in Delo Naroda (The People's Concern), a newspaper run by Victor Chernov. He also wrote for Novaya Zhizn (New Life) a journal funded and edited by Maxim Gorky. In one of these articles he attacked the Soviet government and its Red Terror.

In 1919 Zamyatin published an essay entitled Tomorrow, where he wrote about the importance of maintaining the right to criticize those in authority: "Today is doomed to die - because yesterday died, and because tomorrow will be born. Such is the wise and cruel law. Cruel, because it condemns to eternal dissatisfaction those who already today see the distant peaks of tomorrow; wise, because eternal dissatisfaction is the only pledge of eternal movement forward, eternal creation." Zamyatin went on to add: "The world is kept alive only by heretics: the heretic Christ, the heretic Copernicus, the heretic Tolstoy."

Ignoring warnings about the dangers of what he was doing, Zamyatin published the essay, I Am Afraid, where he argued that the attitude of those in authority was stifling creative literature. Zamyatin argued that "the only weapon worthy of man is the word." He added "fortunately, all truths are false: the essence of the dialectical process is that today's truths become errors tomorrow."

In 1919 Zamyatin was recruited by Maxim Gorky to work with him on his World Literature project. It was the task of Gorky, Zamyatin, Alexander Blok, Nikolai Gumilev, and other members of the editorial board to select, translate and publish non-Russian literary works. Each volume was to be annotated, illustrated, and supplied with an introductory essay.

Zamyatin continued to write fiction and literary criticism and in 1921 his work inspired the creation of Serapion Brothers. The group argued for greater freedom and variety in literature. Members included Nickolai Tikhonov, Mikhail Slonimski, Vsevolod Ivanov and Konstantin Fedin.

In 1923 Zamyatin published Fires of St. Dominic, a book about the Spanish Inquisition, that parallels the activities of the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. He also wrote a series of plays including the popular Attilla. It was through his work with World Literature that Zamyatin discovered the science fiction of H. G. Wells. This inspired him to write the novel We. The first anti-utopian novel ever written, it is a satire on life in a collectivist state in the future. People in this new society called One State, have numbers rather than names, wear identical uniforms and live in buildings built of glass. The people are ruled by the Benefactor and policed by the Guardians. One State is surrounded by a wall of glass and outside is an untamed green jungle.

The hero of We is D-503, a mathematician who is busy building Integral, a gigantic spaceship which will eventually go to other planets to spread the joy of the One State. D-503 is happy with his life until he falls in love with I-330, a member of Mephi, a revolutionary organization living in the jungle. D-503 now joins the plot to take over Integral and use it as a weapon to destroy One State. However, the conspirators are arrested by the Guardians and the Benefactor decides that action must be taken to prevent further revolts. D-503 like the rest of the people living in One State, is forced to undergo the Great Operation, which destroys the part of the brain which controls passion and imagination.

Zamyatin secretly distributed copies of We through literary circles. He was warned by friends that attempts to publish the book in the Soviet Union would led to his arrest and possible execution. Zamyatin knew that he could not be published in the Soviet Union but he managed to smuggle a copy of his manuscript abroad. An English translation of the novel was published in the United States in 1924. Three years later a Russian language edition began to circulate in Eastern Europe.

The publication of We brought fierce criticism from the Soviet Writers' Union. He responded by resigning with the comment that "I find it impossible to belong to a literary organization which, even if only indirectly, takes a part in the persecution of a fellow member."

Zamyatin's plays were banned from the theatre and any books that had been published in the Soviet Union were confiscated. Zamyatin described these events as a "writer's death sentence" and wrote to Joseph Stalin requesting to emigrate claiming that "no creative activity is possible in an atmosphere of systematic persecution that increases in intensity from year to year." He bravely added: " Regardless of the content of a given work, the very fact of my signature has become a sufficient reason for declaring the work criminal. Of course, any falsification is permissible in fighting the devil. I beg to be permitted to go abroad with my wife with the right to return as soon as it becomes possible in our country to serve great ideas in literature without cringing before little men".

It appeared only a matter of time before Zamyatin would be arrested and imprisoned. However, in 1931 Maxim Gorky managed to use his influence over Joseph Stalin to allow Zamyatin to leave the Soviet Union. Zamyatin settled in France where he wrote screenplays such as Anna Karenina. He also wrote an unfinished novel, The Scourge of God, a satire on the Russian Revolution. Yevgeni Zamyatin died of a heart attack in Paris on 10th March, 1937. We, although never published in the Soviet Union, deeply influenced other novels about the future such as Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

On this day in 1895 Beatrice Bakrow, the daughter of Julius Bakrow and Sarah Adler Bakrow, in Oxford Street, Rochester, on 20th January, 1895. According to her biographer, Michael Galchinsky: "She had two brothers, Leonard and Julian. Although few direct references to her Jewishness found their way into her later editorial work and writings, her early life fits the description of upper-middle-class German Jews who thought of themselves as liberal, modern, and forward-looking."

In 1913 Julius Bakrow sent her to Wellesley College but was expelled during her first year for staying out after hours. Her mother met her at the railway station and said: "Beatrice, you've been thrown out of Wellesley. What kind of man will you now?" In 1914 she entered University of Rochester but stayed only a year.

Beatrice Bakrow met the journalist, George S. Kaufman, in 1916, at the wedding of a mutual friend, Allan Friedlich. Howard Teichmann, the author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972), claimed that "Bea had developed into one of those large, unattractive girls who compensate for their lack of beauty by being bright, warm, ambitious, stylish, and charming. There was enough charm, enough style, enough ambition, enough warmth, and enough brightness within her to keep him at her side for the entire evening. Like her father, Bea had a full, slow, and rather lazy way of speaking. She did all the talking, and, characteristically, George listened - with interest."

The following day Beatrice and George drove by motor car to Niagara Falls. On her arrival home, Beatrice told her parents that she was going to marry Kaufman. Julius Bakrow objected to her choice when he discovered he was a journalist. "A vehement argument followed, but Bea stood firm and emerged victorious... Her friends in Rochester were astounded. Not only who was George Kaufman but who were his family, what were they, where did they come from, what business were they in, what did he do for a living, and, of course, the ultimate question: how did his future prospects look?"

Beatrice Kaufman approached his friend, Franklin Pierce Adams, and told him: "Keep the middle of next March open, will you, Frank? I've found a kid upstate who's a peach." Adams, who had observed that the young journalist had never had a girlfriend before, asked: "Are you telling me you're getting married?" Kaufman replied: "Unless it's declared unconstitutional, I am." Adams agreed to be Kaufman's best man at the wedding.

Beatrice and George were married in high-style at the Rochester Country Club on 15th March, 1917. George was too busy with his work at his new post at the New York Times to take a honeymoon. Glancing at the newspapers as they boarded the train that took them back to New York City, George discovered that Tsar Nicholas II had been forced to abdicate. He commented to Beatrice: "Well, it took the Russian Revolution to keep us off the front page."

Beatrice later told a friend: "We were terribly innocent. We were both virgins, which shouldn't happen to anybody." She soon found herself pregnant but unfortunately the child was deformed and stillborn. As their friend, Howard Teichmann, has pointed out: "Beatrice was as crushed as any woman would be, but George's reaction was totally unexpected and heartbreaking to both of them. Following their misfortune, George found himself physically unable to have sexual intercourse with Bea.... There were embarrassed conversations followed by empty promises. First came twin beds, then separate bedrooms, and although George remained Bea's husband, he never again was her lover."

According to Dorothy Michaels Nathan, her friend from childhood, "Beatrice started seeing men even before George started with women." Another friend, the author Alexander King, saw it differently: "Beatrice was one of those great daring women who knows that her husband is having extramarital relations and knows that everybody else knows it, and knows that this can be borne either by throwing fits in lobbies or by being Wife Number One. And she was Wife Number One."

Brian Gallagher, the author of Anything Goes: The Jazz Age of Neysa McMein and her Extravagant Circle of Friends (1987), has argued: "Their lack of sexual experience must have contributed to George's inability to have intercourse with Bea after her miscarriage early in their marriage, and so helped start him on a twenty-year sexual binge... Bea, in the meanwhile, made her own, quite full sexual life, although something of its substitute character is seen in the fact that a majority of the men in it bore a distinct resemblance to George."

Beatrice was determined to establish her own career. At first she was a press agent for three sisters, Constance Talmadge, Norma Talmadge and Natalie Talmadge. Later she worked as a play reader for the Broadway producer, Morris Gest, and as an editor with the publisher, Horace Liveright. It is claimed that she played an important role in discovering and promoting the talent of Clifford Odets, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Djuna Barnes, Bennett Cerf, Oscar Levant, Moss Hart and William Saroyan.

In 1919 George S. Kaufman began taking lunch with a group of young writers in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. One of the members, Murdock Pemberton, later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre. That, I might add, was no means cement for the gathering at any time... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table. Other regulars at these lunches included Beatrice Kaufman, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Franklin Pierce Adams, Donald Ogden Stewart, Edna Ferber, Ruth Hale, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, Frank Crowninshield, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire.

In 1921 Beatrice Kaufman joined the Lucy Stone League. The first list of members included only fifty names. This included Ruth Hale, Heywood Broun, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Franklin Pierce Adams, Anita Loos, Zona Gale, Janet Flanner and Fannie Hurst. Its principles were forcefully expressed in a booklet written by Hale: "We are repeatedly asked why we resent taking one man's name instead of another's why, in other words, we object to taking a husband's name, when all we have anyhow is a father's name. Perhaps the shortest answer to that is that in the time since it was our father's name it has become our own that between birth and marriage a human being has grown up, with all the emotions, thoughts, activities, etc., of any new person. Sometimes it is helpful to reserve an image we have too long looked on, as a painter might turn his canvas to a mirror to catch, by a new alignment, faults he might have overlooked from growing used to them. What would any man answer if told that he should change his name when he married, because his original name was, after all, only his father's? Even aside from the fact that I am more truly described by the name of my father, whose flesh and blood I am, than I would be by that of my husband, who is merely a co-worker with me however loving in a certain social enterprise, am I myself not to be counted for anything."

It is claimed that Beatrice Kaufman was very promiscuous.Howard Teichmann tells the story of how she used to seduce young men: "At one of the larger parties that she and George gave so regularly, Beatrice spotted an attractive young man. There were several bedrooms in the Kaufman apartment, but none seemed appropriate. Stepping out, she and the young man went to the Plaza Hotel, where he signed the register. The room clerk looked over this unlikely couple with no baggage and a single intention." The clerk told the young man that there were no rooms available. When the young man told her this, Beatrice walked up to the desk and exclaimed: "See here, I am Mrs George S. Kaufman!" With this comment the clerk gave them a room.

In 1934 George S. Kaufman became involved in a national scandal. Franklin Thorpe, the husband of the actress Mary Astor, told the newspapers during a custody battle, that his wife's diary revealed that she had been having an affair with Kaufman. The story made the front page of the New York Times. At the time Beatrice was on holiday in London with Edna Ferber, Charles MacArthur, Helen Hayes, Irving Berlin, Margaret Leech and Raoul Fleishmann.

Leech recalled that "Beatrice was terribly upset and embarrassed. Newsman were standing around waiting for her, and she couldn't even go out to a restaurant without being mobbed by them." Fleishmann found her red-eyed from crying in her hotel room: "I'm so sorry. I'm so horribly upset that this should happen to George. I can't stand the thought of how badly he feels."

When they all arrived back in New York City there were at least forty reporters at the pier waiting for them. Beatrice went up to them and said: "I am not going to divorce Mr. Kaufman. Young actresses are an occupational hazard for any man working in the theatre." In the divorce court Mary Astor admitted that she had been having an affair with Kaufman. However, the diary was deemed as admissible and the judge ordered it be sealed and impounded.

In 1935 George S. Kaufman went to work in Hollywood. She wrote about the experience to her mother: "The party at the (Donald Ogden) Stewarts was great fun the other night and my evening was made for me when Mr. Chaplin sat down beside me and stayed for hours. Or did I write you that: I can't remember. He is very amusing and intelligent and I enjoyed talking to him a great deal. Paulette Goddard was there too - very beautiful; everyone says they are married. Joan Bennett, Clark Gable, the Fredric Marches, Dotty Parker, Mankiewiczes, etc. A delicious buffet dinner, with talk and bridge afterwards. Their house is lovely. Saturday night's party which Kay Francis gave was swell, too. She took over the entire Vendome restaurant and had it made over like a ship -a swell job. I seemed to know almost everyone there - there were over a hundred people. A sprinkling of movie stars - James Cagney, the Marches again, June Walker, etc. I arrived home at a quarter to five completely exhausted, having danced and drunk a good deal."

One of their closest friends, Ruth Goetz, later recalled: "They really lived high. Beatrice liked all the goodies of life. She was a great, robustious, fat, yummy woman, bouncy as hell. She loved people and drinking and eating. And she proposed to live that way. She was driven to work by her chauffeur, in her limousine, with a lap robe across her knees. She liked funny people and she liked fellows and she liked women. She was wonderfully hospitable and dear. She wanted a good time, and George was a man who never wanted a good time in his life. I think he had many good times, but they came to him by accident. She had to fill in many a long, dreary spell, which she did. She filled it with thousands of friends and a household that she ran extremely lavishly. Beatrice and George, in a curious way, they made it with that marriage, they really did. It was totally unsuited. The things she liked, he didn't. But he would have had no friends without her. She served her end of the marriage and he his. The marriage was on the surface, although one knew that the core was out of it and had been for many years. Still she really loved him. And so it worked. If one person goes on loving, it can be managed."

Edna Ferber thought that despite her many affairs, Beatrice was a good wife: "The wonderful Beatrice was the great influence in George's life. Sustaining, warm, perceptive, enormously companionable, she could go out to the corner to mail a letter and make the errand sound more adventurous and amusing than Don Quixote's journeyings." Another friend, Esther Adams, the wife of Franklin Pierce Adams, commented "Beatrice was like putting your hands in front of a warm stove. She was so appreciative and humorous."

After several years of poor health, Beatrice Kaufman died at six o'clock in the evening on 5th October, 1945. Moss Hart entered the room five minutes later and found George Kaufman beating his head against the wall. He had always consulted Beatrice when he was writing plays. Arthur Kober said: "George valued her opinion probably more than anyone else." At the funeral he told his friend Russel Crouse, "I'm finished. Through. I'll never write again."

On this day in 1900 art critic John Ruskin, the only child of John James Ruskin (1785–1864), a sherry importer, and Margaret Cock (1781–1871), was born on 8th February 1819, at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London. In 1823 the Ruskin family moved to a semi-detached house with a large garden at 28 Herne Hill, Herne Hill. His father was chief partner in firm of Ruskin, Telford, and Domecq, that imported and distributed sherry and other wines.

Ruskin was educated by his parents, with the help of private tutors, until the age of fourteen. His father encouraged a love of Lord Byron and William Wordsworth. His mother was a devout Christian. Every morning, from the age of three, his mother made him read from the Bible and learn passages by heart. According to Robert Hewison: "Ruskin's certainty in the rightness of his views and independence from received opinion - his critics might say his dogmatism - is attributable to his mother's cast of mind. Yet the conflict between his father's expressive desire and his mother's cautious restraint was to undermine his apparent confidence throughout his life... The puritanism of his religion was in conflict with the sensual appeal of much of the art that he was to study, and inhibited the enjoyment of his own body. " Ruskin gives an unfinished account of his childhood in Praeterita (1885), but most historians consider it untrustworthy. In 1828 he was joined from Perth by his cousin Mary Richardson, whose mother had died.

In 1833 he spent his mornings at a day school run by the Revd Thomas Dale of St Matthew's Chapel, a Church of England establishment in Denmark Hill. In 1836 he attended lectures at King's College, where Dale had become the first professor of English literature. In October of that year he enrolled at Christ Church. At Oxford University he wrote a series of essays linking architecture and nature for Loudon's Architectural Magazine.

Ruskin was an extremely shy man and made few friends at university. However, he did develop good relationships with two fellow students, Charles Thomas Newton and Henry Acland. Ruskin spent most of his time reading books and writing and in 1839 won the Newdigate Poetry Competition. Ruskin had the pleasure of meeting one of his heroes, William Wordsworth, when presented with the prize.

Ruskin had developed an adolescent passion for the daughter of his father's partner, Pedro Domecq. Adèle, was the subject of much of Ruskin's youthful poetry. She was only fifteen when he first fell in love with her and was devastated when he learned of her engagement. In April 1840, shortly after Adèle's marriage, Ruskin suffered a mental breakdown. After two years of rest he returned to Oxford University where he achieved the unusual distinction of an honorary double fourth, taking his MA in October 1843.

Ruskin took a keen interest in art and at university gained a reputation as a skilled water-colourist. He wrote that he had "a sensual faculty of pleasure in sight, as far as I know unparalleled." Robert Hewison has argued: "Ruskin's perceptual sensibility, and his ability to deploy it both as a draughtsman and a visual analyst, marks him out from his more book-bound peers... although his drawings would justify the appellation, he never considered himself an artist, emphasizing always that he drew in order to gain certain facts, and he exhibited rarely. None the less, Ruskin's drawings are a remarkable achievement, both as a record of his mind, and as works of great beauty. His ability visually to depict architecture and landscape was matched by his genius for the verbal description of works of art."

Ruskin developed a great passion for the work of J. M. W. Turner. Soon after graduating he met Turner and began purchasing his work. In 1842 Ruskin and his father became patrons as well as collectors, when Turner's dealer Thomas Griffith included them in an invitation to Turner's circle of patrons to commission finished watercolours based on preliminary sketches. Later that year Ruskin read a newspaper review of that year's Royal Academy Exhibition, attacking Turner's contributions. Ruskin was furious and wrote that he was "determined to write a pamphlet and blow the critics out of the water".

Ruskin's father offered to support him financially in this venture and he eventually decided to write a series of books on modern art. The first volume of Modern Painters: their Superiority in the Art of Landscape Painting to the Ancient Masters, appeared in 1843. Ruskin wrote that "There is a moral as well as material truth - a truth of impression as well as of form - of thought as well as of matter." The author of John Ruskin (2007) has explained: "Such truths depended on a clarity of perception that was free of the pictorial conventions of the seventeenth-century Italian and Dutch masters who set the norm for received taste in landscape painting... Ruskin substituted a different way of seeing, that of the geologist and botanist, deploying the accuracy of observation encouraged by the classificatory sciences that did not conflict with natural theology."

In the book, Ruskin boldly proclaimed "the superiority of the modern painters to the old ones" and eulogized about the work of his great hero, J. M. W. Turner. The art critic, Patrick Conner, has pointed out: "Ruskin was scathing in his analysis of many of the established masters of the seventeenth-century painting, but won respect nevertheless for his acute observation of nature and for his lyrical evocations of Turner's art." After reading the book, Charlotte Bronte wrote: "I feel now as if I had been walking blindfold - this book seems to give me eyes." Ruskin also received support from William Wordsworth and Elizabeth Gaskell, who claimed that Ruskin was "no ordinary man". However, Ruskin's challenge to an aesthetic orthodoxy derived from Sir Joshua Reynolds drew strong disapproval from John Eagles in Blackwood's Magazine (October 1843) and from George Darley in The Athenaeum (February 1844).

In 1845 John Ruskin spent time in Italy studying the work of the fourteenth and fifteenth-century artists of Pisa, Florence and Venice. It was these artists, together with Fra Angelico and Jacopo Tintoretto, who were the heroes of the second volume of Modern Painters (1846). Ruskin attempted to show that truthful perception of nature led to an experience of beauty that was also an apprehension of God. Ruskin divided beauty into two categories, "vital" and "typical’. According to Robert Hewison: "Vital beauty, in accordance with natural theology, expresses God's purpose in the harmonious creation of the world and its creatures, including man. Typical beauty, in accordance with evangelical typology, expresses the immanence of God in the natural world through the presence of ‘types’ to which man responds as beautiful. These types are qualities rather than things: infinity, unity, repose, purity, and symmetry. They are associated with divine qualities and can be found in nature and in art, but though abstract themselves, they have a real presence that it is the artist's duty truthfully to represent. Through his mother's training and the sermons he heard every Sunday, Ruskin had absorbed the evangelical practice of treating objects as both real and symbolic at the same time, a key critical practice that remained a feature of his writings throughout his life." Virginia Woolf later argued: "The style in which page after page of Modern Painters is written takes our breath away. We find ourselves marvelling at the words, as if all the fountains of the English language had been set playing in the sunlight for our pleasure, but it seems scarcely fitting to ask what meaning they have for us."

Ruskin met Effie Gray in October, 1847. He fell in love with the nineteen year-old and on his return to London, he wrote to George Gray asking to marry his daughter. Ruskin's parents raised no objections to the marriage, but preparations for the wedding in the following year were marred by Gray's near bankruptcy as a result of railway speculation. The wedding took place at Bowerswell House on 10th April 1848.

Effie later wrote to her father explaining that her marriage had not been consummated. "He alleged various reasons, hatred to children, religious motives, a desire to preserve my beauty, and, finally this last year he told me his true reason... that he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April." Robert Hewison has argued: "This has been interpreted as meaning that Ruskin was equally innocent, especially in the matter of female pubic hair, but this seems unlikely, as he had seen erotic images belonging to fellow undergraduates at Oxford. There is also speculation that Effie's menstrual cycle interfered with consummation, which is plausible but not provable."

Ruskin admitted that he loved Effie passionately when he met her for the first time in 1840. After they were married he wistfully told her that "the sight of you, in your girlish beauty, which I might have had." As Suzanne Fagence Cooper, the author of The Passionate Lives of Effie Gray, Ruskin and Millais (2012) has pointed out: "John Ruskin loved young girls, innocents on the verge of womanhood. He became enchanted with twelve-year-old Effie when she visited Herne Hill in the late summer of 1840. The next time he saw her, John Ruskin felt she was 'very graceful but had lost something of her good looks'. After he had won her hand in 1847 and she was still only nineteen... Effie was too old to be truly desirable."

After returning from their honeymoon they lived at Denmark Hill and at a rented house at 31 Park Street, Mayfair. During this period John Ruskin was working on his book, The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Published in May 1849, the book was illustrated with fourteen plates drawn and etched by him. Ruskin attempted to draw the attention of the public to the merits of pre-Renaissance Italian architecture, and thereby broaden the scope of the Gothic Revival in Britain.

Effie Ruskin was unhappy with the state of her marriage and in February 1849, she returned to her parents in Perth and did not see her husband for nine months. In September Ruskin somewhat reluctantly travelled north to collect her. Three weeks later they set out for Venice. On their return to London their social and intellectual circle began to grow. This included Charles Eastlake, president of the Royal Academy and director of the National Gallery, and Frederick Denison Maurice, the leader of the Christian Socialist movement. Another friend was the poet, Coventry Patmore, who introduced him to members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB).

In 1851 Ruskin published the first volume of The Stones of Venice. According to the art historian, Patrick Conner: "These books exerted a fundamental influence on Victorian attitudes to architecture... Ruskin... exemplified his conception that a work of art reflects the personality of its creator - and in the case of architecture, a collective personality or age-spirit, whose growth, health and decay could be traced even in the smallest details of architectural decoration."

On the 7th May, 1851, The Times accused three members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Charles Allston Collins of “addicting themselves to a monkish style”, having a “morbid infatuation” and indulging in “monkish follies”. Finally, the works are dismissed as un-English, “with no real claim to figure in any decent collection of English painting.” Six days later John Ruskin had a letter published in the newspaper, where he came to the defence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In another letter published on 30th May, Ruskin claimed that PRB “may, as they gain experience, lay in our land the foundations of a school of art nobler than has been seen for three hundred years”.

John Ruskin now published a pamphlet entitled, Pre-Raphaelitism (1851). He argued that the advice he had given in the first volume of Modern Painters had “at last been carried out, to the very letter, by a group of young men who... have been assailed with the most scurrilous abuse... from the public press.” Aoife Leahy has argued: "Ruskin’s defences had now taken a new and decidedly evangelical tone. He had formed friendships with the Pre-Raphaelite artists on the basis of his letters to The Times and, just as significantly, he had been personally harassed by members of the public for his views."

John Ruskin became a close friend of John Everett Millais and agreed that Effie Ruskin should pose as the freed Jacobite prisoner's wife, in the painting, The Order of Release, 1746 (1853). Later that year Ruskin invited Millais and William Holman Hunt to go on holiday with them to Scotland. Hunt refused but Millais accepted the offer. In July they stayed in a rented cottage near Stirling. During their stay, Millais began painting portraits of Effie and Ruskin.

In November, Ruskin went on to lecture in Edinburgh whereas Millais returned to London. He had fallen in love with Effie and they continued to see each other over the next few months. On 25th April 1854 Ruskin accompanied his wife to King's Cross railway station to see her off on a visit to her parents in Scotland. That evening Ruskin was served with a legal citation at Denmark Hill, claiming the nullity of the marriage.

A medical examination confirmed Effie's virginity, but in a legal deposition that was not introduced in court, John Ruskin stated: "I can prove my virility at once." Robert Hewison has pointed out: "This was never put to the test, but it seems likely that Ruskin was referring to masturbation." He also told a male friend that he had been capable of consummating his marriage, but that he had not loved Effie sufficiently to want to do so." Following an undefended hearing in the ecclesiastical commissary court of Surrey on 15th July, the marriage was annulled on the grounds that "the said John Ruskin was incapable of consummating the same by reason of incurable impotency".

Ruskin wrote a letter to John Everett Millais stating that he wanted to remain friends. Millais replied: "I can scarcely see how you conceive it possible that I can desire to continue on terms of intimacy with you". Millais married Effie on 3rd July, 1855 and over the next few years she gave birth to eight children.

Ruskin was greatly influenced by the work of Thomas Carlyle. He agreed with his criticisms of the industrial revolution and in The Stones of Venice: Volume II (1853) Ruskin argued that the working man had been reduced to the condition of a machine: "We have much studied and much perfected, of late, the great civilized invention of the division of labour; only we give it a false name. It is not, truly speaking, the labour that it divided; but the men; - divided into mere segments of men - broken into small fragments and crumbs of life; so that all the little piece of intelligence that is left in a man is not enough to make a pin, or a nail, but exhausts itself in making the point of a pin or the head of a nail. Now it is a good and desirable thing, truly, to make many pins in a day; but if we could only see with what crystal sand their points were polished, - sand of human soul, much to be magnified before it can be discerned for what it is - we should think that there might be some loss in it also. And the great cry that rises from our manufacturing cities, louder than their furnace blast, is all in very deed for this, - that we manufacture everything there except men; we blanch cotton, and strengthen steel, and refine sugar, and shape pottery; but to brighten, to strengthen, to refine, or to form a single living spirit, never enters into our estimate of advantages. And all the evil to which that cry is urging our myriads can be met only in one way: not by teaching nor preaching, for to teach them is but to show them their misery, and to preach at them, if we do nothing more than preach, is to mock at it. It can only be met by a right understanding, on the part of all classes, of what kinds of labour are good for men, raising them, and making them happy; by a determined sacrifice of such convenience or beauty, or cheapness as is to be got only by the degradation of the workman; and by equally determined demand for the products and results of healthy and ennobling labour." William Morris later recalled: "To some of us when we first read it, now many years ago, it seemed to point out a new road on which the world should travel".

Ruskin gave a series of lectures on J. M. W. Turner, Gothic Architecture and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Edinburgh in 1853. The Edinburgh Guardian reported: "Mr Ruskin has light sand-coloured hair; his face is more red than pale; the mouth well cut, with a good deal of decision in its curve, though somewhat wanting in sustained dignity and strength; an aquiline nose; his forehead by no means broad or massive, but the brows full and well bound together; the eye we could not see… Mr Ruskin's elocution is peculiar; he has a difficulty in sounding the letter ‘r’; but it is not this we now refer to, it is the peculiar tone in the rising and falling of his voice at measured intervals, in a way scarcely ever heard except in the public lection of the service appointed to be read in churches. These are the two things with which, perhaps, you are most surprised, - his dress and his manner of speaking, - both of which (the white waistcoat notwithstanding) are eminently clerical."

Despite his dispute with John Everett Millais, Ruskin continued to support the Pre-Raphaelites. In 1854 Ruskin wrote to The Times, praising the latest work of William Holman Hunt. This included The Light of the World (5th May) and The Awakening Conscience (25th May). Ruskin also pointed out the abilities of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He also bought and commissioned drawings from Rossetti and his mistress, Elizabeth Siddal. Ruskin also encouraged his American friend Charles Eliot Norton, to buy Rossetti's paintings.

The art critic, Patrick Conner, has argued that Ruskin's writings inspired artists such as William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: "Ruskin... proved an inspiration to William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, whose enthusiasm carried Pre-Raphaelite principles into many branches of the decorative arts. They inherited from Ruskin a hostility to classical and Renaissance culture which extended to the arts and design of their own time. Ruskin and his followers believed that the nineteenth century was still afflicted by a demand for mass-production... They opposed themselves to mechanized production, meaningless ornament and anonymous architecture of cast iron and plate glass."

Ruskin became interested in socialism. Between 1854 and 1858 he taught at the Working Men's College that had been founded by Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes in London. In his lectures Ruskin denounced greed as the main principle guiding English life. In books such as Unto the Last (1862) Essays on Political Economy (1862) and Time and Tide (1867), Ruskin argued against competition and self-interest and advocated a form of Christian Socialism.

In January 1858 Ruskin met John La Touche, a wealthy Irish banker. He became a regular visitor to La Touche's home in London and got to know his wife Maria and daughter, Rose La Touche. In his autobiography, Præterita: Outlines of Scenes and Thoughts Perhaps Worthy of Memory in My Past Life (1885), Ruskin wrote about his first meeting with Rose: "On presently the drawing room door opened, and Rosie came in, quietly taking stock of me with her blue eyes as she walked across the room; gave me her hand, as a good dog gives its paw, and then stood a little back. Nine years old, on 3rd January, 1858, thus now rising towards ten; neither tall nor short for her age; a little stiff in her way of standing. The eyes rather deep blue at that time, and fuller and softer than afterwards. Lips perfectly lovely in profile;--a little too wide, and hard in edge, seen in front; the rest of the features what a fair, well-bred Irish girl's usually are; the hair, perhaps, more graceful in short curl around the forehead, and softer than one sees often, in the close-bound tresses above the neck."

Ruskin gave Rose drawing lessons. Ruskin wrote letters to Rose and he kept her replies "wrapped in gold leaf, tucked inside his waistcoat, close to his heart." According to Ruskin's biographer, Robert Hewison: "By the autumn of 1861 Ruskin felt deeply drawn towards Rose, but that October she fell ill for the first time from the psychosomatic disorder (possibly the as yet unrecognized condition anorexia nervosa)... Ruskin's preference for daughter over mother may have caused some tension... He did not see Rose between the spring of 1862 and December 1865, though Mrs La Touche did not break off contact. Rose had further bouts of illness in 1862 and 1863. Like other men of his class and culture... Ruskin enjoyed the company of young girls... It was their purity that attracted him; any sexual feelings were sublimated in the playful relationship of master and pupil that characterized his letters to several female correspondents."

Ruskin's father died on 3rd March 1864. His inheritance was £157,000, pictures worth at least £10,000, and property in the form of houses and land. Ruskin believed it was wrong to be a socialist and rich and he donated a great deal of his money to causes such as the St George's Guild in Paddington, the Whitelands College in Chelsea and the John Ruskin School in Camberwell.

In January, 1866, Ruskin, aged forty-six, proposed marriage to nineteen year old, Rose La Touche. She did not reject Ruskin but asked him to wait for three years. John La Touche and his wife were opposed to the marriage and Ruskin was only able to communicate with Rosa by using intermediaries, such as George MacDonald, Georgiana Cowper and Joan Agnew.

On 7th January, 1870, Ruskin met Rose accidentally at the Royal Academy. Rose, who was now 23 years old, began to see Ruskin on a regular basis. John and Maria La Touche became increasingly concerned about the possibility that her daughter might marry Ruskin. In October, 1870, Marie wrote to Effie Millais seeking evidence of Ruskin's impotence in order to stop the marriage. Effie confirmed this and stated that Ruskin was "utterly incapable of making a woman happy". She added that "he is quite unnatural... and his conduct to me was impure in the highest degree." She ended her letter by saying, "My nervous system was so shaken that I never will recover, but I hope your daughter will be saved."

John Everett Millais became concerned about the impact that this correspondence was having on his wife. He wrote to Rose's parents begging them to leave his wife alone. He insisted that "the facts are known to the world, solemnly sworn in God's house" and asked why this "indelicate enquiry necessary". Millais then went on to argue that Ruskin's "conduct was simply infamous, and to this day my wife suffers from the suppressed misery she endured with him." Millais feared that a consummated marriage with Rose would render the previous grounds for annulment void, and would make his marriage to Effie bigamous.

In July 1871 Rose La Touche broke off her relationship with Ruskin. Shocked by the news, he suffered a mental breakdown while staying Matlock Bath in Derbyshire. Rosa's health was also deteriorating. In an effort to help her recover, they gave permission for Ruskin to visit her at their estate in Harristown, County Kildare. In January 1875, she returned to London, but extremely ill, and Ruskin saw her for the last time on 15th February, before she was taken to Dublin in April. Rose died on 25th May, aged twenty-seven. Suzanne Fagence Cooper, the author of The Passionate Lives of Effie Gray, Ruskin and Millais (2012), has pointed out that "she died of anorexia, or brain fever, or a broken heart, depending on which account you believe". Ruskin later wrote: "Rose, in heart, was with me always, and all I did was for her sake."

In 1871 Ruskin began publication of Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain. He wrote: "Whose fault is it, you cloth-makers, that any English child is in rags? Whose fault is it, you shoemakers, that the street harlots mince in high-heeled shoes and your own babies paddle bare-foot in the street slime? Whose fault is it you bronzed husbandmen, that through all your furrowed England, children are dying of famine?" Ruskin blamed the capitalist system for these problems. Between 1871 and 1878 it was issued in monthly parts. Ruskin intended the work to be a "continual challenger to the supporters of and apologists for a capitalist economy". It was Ruskin's socialist writing that influenced trade unionists and political activists such as Tom Mann and Ben Tillett.

Ruskin suffered a complete mental breakdown in February 1878. He later wrote to a friend, Charles Eliot Norton: "Mere overwork or worry, might have soon ended me, but it would not have driven me crazy. I went crazy about St Ursula and the other saints." It has been noted that "Ruskin's delusions during his first attack of what has been characterized as either manic depression or paranoid schizophrenia." Ruskin retreated to his home at Brantwood, across the lake from the village of Coniston.

Despite several bouts of mental illness, Ruskin was able to complete The Art of England in 1884. This was followed by The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1885). He also began work on his autobiography, Præterita: Outlines of Scenes and Thoughts Perhaps Worthy of Memory in My Past Life. His biographer, Robert Hewison, has commented: "Praeterita is a delightful work, a rewriting of Ruskin's life that makes it unreliable as a source of biographical fact, yet an accurate portrait of the author's mind. That it remained unfinished shows that the contradictions of that mind never achieved their desired synthesis, though this version is the best that could be achieved, and makes it a significant work of literature, most especially in his Wordsworthian evocation of the power of nature on the growth of a young mind. The conscious manipulation of memory had been intended to be therapeutic, but there were memories and hurts that could not be suppressed, and as Ruskin struggled to bring them out he found himself fighting a double battle: to retain his sanity, and to control the composition of the work."

At the end of July 1885, just as the first two sections of Præterita describing his family background and early childhood appeared, Ruskin had a fourth, longer, and more severe attack of madness. He attempted to finish his autobiography but had only reached 1858, the year when he met Rose La Touche, when he was forced to abandon the project after suffering another serious breakdown. He gradually retreated into silence, saying little, and writing few letters.

John Ruskin died of influenza on 20th January, 1900.

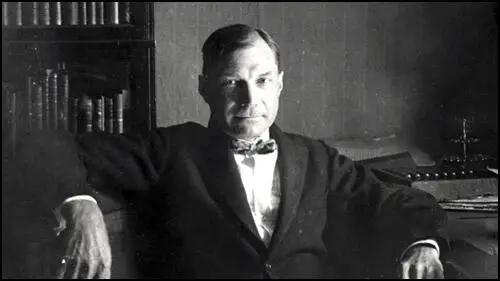

On this day in 1915 Don B. Reynolds, the man who exposed political corruption, was born. A graduate of West Point. He joined the United States Army Airforce (USAAF) and after the Second World War he served as a U.S. consular official in Berlin.

On his return to the United States he established a company called Don Reynolds Associates in Silver Spring, Maryland. Reynolds was a friend of Bobby Baker, who was at this time working for Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1957 Reynolds was asked to arrange Johnson's life insurance policy. "That was in 1957, only two years after Senate Majority Leader Johnson had suffered a heart attack. The Senator was having trouble finding an insurance company that would give him life insurance. Reynolds went looking on Johnson's behalf, talked to three companies, and finally found that the Manhattan Life Insurance Co. would write the policy. Manhattan issued a first policy of $50,000, and shortly afterward, when it had covered part of its risk through a reinsurance company, issued another policy of $50,000 for Johnson."

Baker also introduced Reynolds to a large number of people that resulted in him signing insurance deals. This included Harry S. Truman, Jimmy Hoffa, Fred Black, Matthew H. McCloskey and Nancy Carole Tyler. "I had entered into an agreement with Reynolds, a fellow South Carolinian, to steer insurance customers to him in exchange for a small piece of the business and a commission on any policies he wrote as a result of my efforts." Reynolds later claimed that over ten years he had "paid Baker some $15,000 for putting him in touch with the right people."

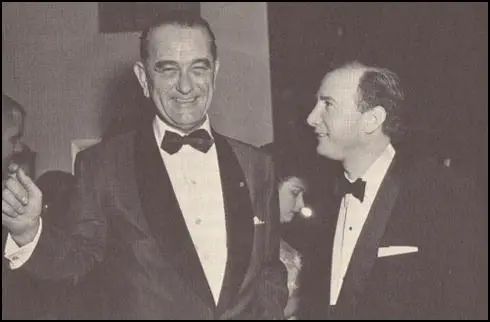

By 1963 John F. Kennedy realised that Lyndon B. Johnson had become a problem as vice-president as he had been drawn into political scandals involving Fred Korth, Billie Sol Estes and Bobby Baker. According to James Wagenvoord, the editorial business manager of Life, the magazine was working on an article that would have revealed Johnson's corrupt activities. "Beginning in later summer 1963 the magazine, based upon information fed from Bobby Kennedy and the Justice Department, had been developing a major newsbreak piece concerning Johnson and Bobby Baker. On publication Johnson would have been finished and off the 1964 ticket (reason the material was fed to us) and would probably have been facing prison time. At the time LIFE magazine was arguably the most important general news source in the US. The top management of Time Inc. was closely allied with the USA's various intelligence agencies and we were used after by the Kennedy Justice Department as a conduit to the public."

The fact that it was his brother Robert Kennedy who was giving this information to Life Magazine suggests that Kennedy intended to drop Johnson as his vice-president. This is supported by Evelyn Lincoln, Kennedy's secretary. In her book, Kennedy and Johnson (1968) she claimed that in November, 1963, Kennedy decided that because of the emerging Bobby Baker scandal he was going to drop Johnson as his running mate in the 1964 election. Kennedy told Lincoln that he was going to replace Johnson with Terry Sanford, the Governor of North Carolina.

Phil Brennan, a journalist working for The National Review, argued that the Washington press corps had buried the stories about the Bobby Baker scandal and the connections with Johnson. However, John J. Williams, the Republican Party senator for Delaware, called upon the Committee on Rules and Administration to conduct an investigation of the financial and business interests and possible improprieties of Baker. Brennan points out: "A few days later, the attorney general, Bobby Kennedy, called five of Washington's top reporters into his office and told them it was now open season on Lyndon Johnson. It's OK, he told them, to go after the story they were ignoring out of deference to the administration."

John Williams was known as "Honest John" and "the conscience of the Senate" because of his investigations into the corrupt activities of officials in the Harry S. Truman and the Dwight D. Eisenhower administrations. This included the downfall of General Harry H. Vaughan (1951) and Sherman Adams (1958). In September 1963 Williams began to look into the business activities of Bobby Baker. On 7th October, Baker resigned from his post as Johnson's Senate's Secretary. Three days later, Williams introduced a resolution calling for an investigation by the Senate Rules Committee.

"The Senate, which has never been reluctant to call to task officials of the Executive Branch when questions were raised concerning the propriety of their conduct, but an even greater responsibility to examine these charges that are being made against one of its own employees... The Senate employee against whom the charges were made was given ample opportunity to appear in person and answer these charges but he rejected this invitation and instead submitted his resignation."

According to Senator Carl Curtis of Nebraska, a member of he Committee on Rules and Administration, Williams suggested that Reynolds should be interviewed about his relationship with Baker and Johnson. Curtis later recalled that when he testified in closed session Williams recommended the Committee investigate the FBI files of a deported East German woman, Ellen Rometsch, who had been identified as associating with lobbyists and members of Congress. Williams also urged the Committee to investigate the Serv-U Corporation, a company set up by Bobby Baker in partnership with Fred Black, Eugene Hancock, Grant Stockdale and George Smathers. He also raised questions about Johnson's close friends such as Cliff Carter and Walter Jenkins.

Bobby Baker refused to testify before the Committee: "I knew, however, that if I testified to the total truth then Lyndon B. Johnson, among others, might suffer severely. Suppose they asked me whether Lyndon Johnson had, indeed, insisted on a kickback from Don Reynolds in the writing of his life insurance policy? A truthful answer would torpedo the vice-president. Suppose they asked me what I knew of campaign funds for Johnson, or for the matter President Kennedy? Although I sensed that a 'gentleman's agreement' had been reached with respect to avoiding the embarrassment of senators, I certainly suspected that John J. Williams would not honor it where the vice-president was concerned. I had been too recently a member of the club, and too keenly felt a kinship with LBJ and others, to turn rat. You may say that I was honoring the code of the underworld if you will, but I didn't want to hurt my friends."

Seth Kantor of the Fort Worth Press, Clark R. Mollenhoff of the Des Moines Register and Erwin Knoll of the Washington Post began to examine Baker's business activities. They became especially interested in a house purchased by Baker in Washington. It was occupied by Nancy Carole Tyler, a former Tennessee beauty-contest winner, who was Baker's $8,300-a-year private secretary at the Senate. The house was purchased in Baker's name, and Tyler was listed as his "cousin" in the application. Tyler was Baker's mistress rather than his cousin.

In his autobiography Baker admitted that he was guilty of this offence: "I had incorrectly and improperly listed Carole Tyler as my cousin when I applied for the loan, in order to satisfy the Federal Housing Authority's regulation that anyone buying an FHA-underwritten home must either live in it or have a relative living in it. At the time I gave the matter little more serious thought than would a groundhog; indeed, Carole and I had shared a laugh about it. Well, I said to my lover, at least you're my kissin' cousin. So it's only a little white lie."

At a closed session on 22nd November, 1963, Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his Committee on Rules and Administration that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for him agreeing to this life insurance policy. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds was also told by Walter Jenkins that he had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Senator Robert Byrd asked Reynolds if he had evidence that the stereo was a gift from him. Reynolds replied "The invoice delivered to Johnson's home showed that the charges were to be Reynolds."

In his autobiography, Wheeling and Dealing (1978), written many years later, Baker admitted that Reynolds was telling the truth about being forced to advertise on KTBC: "Johnson was supersensitive to criticism that he used his public offices to add to his personal wealth, which was founded on radio and television properties. He avidly promoted the fiction that Lady Bird Johnson was the business genius... It was no accident that Austin, Texas, was for years the only city of its size with only one television station. Johnson had friends in high places among those who controlled the broadcast industry. George Smathers was his man in the Senate. Bob Bartley, a member of the Federal Communications Commission, just happened to be a nephew to LBJ's patron, Speaker Sam Rayburn."

Don B. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Bobby Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". Reynolds also provided evidence against Matthew H. McCloskey. He suggested that he given $25,000 to Baker in order to get the contract to build the District of Columbia Stadium. According to the New York Times: "He (Reynolds) charged that Mr. Baker had received a $25,000 contribution for the 1960 Democratic Presidential campaign from Matthew H. McCloskey, builder of the $20 million D. C. Stadium in Washington, a prominent Democratic fund-raiser. The contribution, he said, was in the form of an overpayment by the McCloskey concern for a premium on a performance bond for the stadium that Mr. Reynolds's company had written. Mr. Reynolds said he had turned the money over to Mr. Baker on Mr. McCloskey's instructions."

Reynolds' testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds.