On this day on 14th June

On this day in 1381 Richard II agrees to meet Wat Tyler, the leader of the Peasants Revolt, at Mile End. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End".

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract".

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London.

John Ball at Mile End from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

On this day in 1645 the Battle of Naseby takes place. In February 1645, Parliament decided to form a new army of professional soldiers and amalgamated the three armies of William Waller, Earl of Essex and Earl of Manchester. This army of 22,000 men became known as the New Model Army. Its commander-in-chief was General Thomas Fairfax, while Oliver Cromwell was put in charge of its cavalry.

Members of the New Model Army received proper military training and by the time they went into battle they were very well-disciplined. In the past, people became officers because they came from powerful and wealthy families. In the New Model Army men were promoted when they showed themselves to be good soldiers. For the first time it became possible for working-class men to become army officers. Oliver Cromwell thought it was very important that soldiers in the New Model Army believed strongly in what they were fighting for. Where possible he recruited men who, like him, held strong Puritan views and the New Model Army went into battle singing psalms, convinced that God was on their side.

The New Model Army took part in its first major battle just outside the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire on 14th June 1645. The battle began when Prince Rupert led a charge against the left wing of the parliamentary cavalry which scattered and Rupert's men then gave chase.

While this was going on Oliver Cromwell launched an attack on the left wing of the royalist cavalry. This was also successful and the royalists that survived the initial charge fled from the battlefield. While some of Cromwell's cavalry gave chase, the majority were ordered to attack the now unprotected flanks of the infantry.

Charles I was waiting with 1,200 men in reserve. Instead of ordering them forward to help his infantry he decided to retreat. Without support from the cavalry, the royalist infantry realised their task was impossible and surrendered.

By the time Prince Rupert's cavalry returned to the battlefield the fighting had ended. Rupert's cavalry horses were exhausted after their long chase and were not in a fit state to take on Cromwell's cavalry. Prince Rupert had no option but to ride off in search of Charles I.

The battle was a disaster for the king. About 1,000 of his men had been killed, while another 4,500 of his most experienced men had been taken prisoner. The Parliamentary forces were also able to capture the Royalist baggage train that contained his complete stock of guns and ammunition.

The Battle of Naseby was the turning point in the war. After Naseby, Charles was never able to raise another army strong enough to defeat the parliamentary army in a major battle.

On this day in 1811 Harriet Beecher Stowe, the daughter of the Congregationalist minister, Lyman Beecher, was born in Litchfield, Connecticut. Her brother was the famous preacher, Henry Ward Beecher. After an education at the Connecticut Female Seminary she taught at schools in Hartford and Cincinnati.

In 1834 Harriet began to write short stories for the Western Monthly. Two years later she married the Rev. Calvin Ellis Stowe, a clergyman and biblical scholar. Over the next few years Harriet had seven children but continued to write stories and articles for numerous magazines.

Harriet was converted to anti-slavery campaign after hearing Theodore Weld speak at a public meeting. She was determined to do something to help the cause. One day, while in church, she decided to write a novel about slavery. The main character in the book was based on Josiah Henson, an escaped slave whose narrative Harriet had read. Weld's book, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, also provided her with plenty of background material.

Uncle Tom's Cabin was written as a serial and began appearing in the anti-slavery journal, The National Era, in 1851. It was published in book form the following year. In the preface Stowe wrote: "The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows, under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away with the good effects of all that can be attempted for them by their best friends."

The publisher decided to print 5,000 copies of Uncle Tom's Cabin. It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition sold out in seven days. Despite being banned in the South, over 300,000 copies were sold in its first year. As Frederick Douglass was later to point out: "Its effect was amazing, instantaneous and universal".

Translated into many languages, Uncle Tom's Cabin was also a great success in Europe. In England alone over a million copies were sold. Supporters of slavery were furious and Stowe received hundreds of hostile letters. Thirty pro-slavery novels were published in an attempt to reverse public sympathies in what had now become a propaganda battle. Stowe responded by publishing The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), a book of source material on slavery.

Stowe visited England where she met Queen Victoria. She also made three tours of Europe and this inspired her book Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (1854). A second anti-slavery novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp appeared in 1856. The story of a slave rebellion was followed by The Minister's Wooing (1859).

Other books written by Stowe include Agnes of Sorrento (1862), Oldtown Folks (1869) Pink and White Tyranny (1871) and We And Our Neighbours (1875).

Harriet Beecher Stowe died on 1st July, 1896.

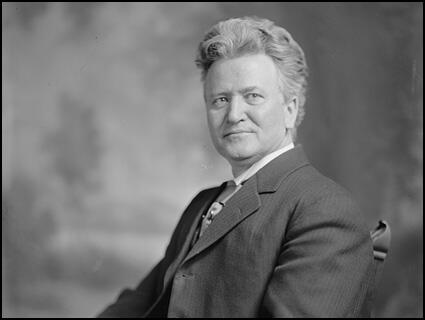

On this day in 1855 Robert M. La Follette, the son of a small farmer, was born in Dane County, Wisconsin. He worked as a farm labourer before entering the University of Wisconsin in 1875.

In 1876 La Follette met Robert G. Ingersoll. He later recalled: "Ingersoll had a tremendous influence upon me, as indeed he had upon many young men at the time. It was not that he changed my beliefs, but he liberated my mind. Freedom was what preached: he wanted the shackles off everywhere. He wanted men to think boldly about all things: he demanded intellectual and moral courage." After graduating in 1879 he set up as a lawyer and the following year became District Attorney of Dane County.

Elected to Congress as a Republican, La Follette was extremely critical of the behaviour of some of the party bosses. In 1891, La Follette announced that the state Republican boss, Senator Philetus Sawyer, had offered him a bribe to fix a court case.

Over the next six years La Follette built up a loyal following within the Republican Party in opposition to the power of the official leadership. Proposing a programme of tax reform, corporation regulation and an extension of political democracy, La Follette was elected governor of Wisconsin in 1900.

Once in power La Follette employed the academic staff of the University of Wisconsin to draft bills and administer the laws that he introduced. He later recalled: "I made it a policy, in order to bring all the reserves of knowledge and inspiration of the university more to the service of the people, to appoint experts from the university wherever possible upon the important boards of the state - the civil service commission, the railroad commission and so on - a relationship which the university has always encouraged and by which the state has greatly profited."

La Follette was also successful in persuading the federal government to introduce much needed reforms. This included the regulation of the railway industry and equalized tax assessment. In 1906 La Follette was elected to the Senate and over the next few years argued that his main role was to "protect the people" from the "selfish interests". He claimed that the nation's economy was dominated by fewer than 100 industrialists. He went on to argue that these men then used this power to control the political process. La Follette supported the growth of trade unions as he saw them as a check on the power of large corporations.

In 1909 La Follette and his wife, the feminist, Belle La Follette founded the La Follette's Weekly Magazine. The journal campaigned for women's suffrage, racial equality and other progressive causes. Lincoln Steffens argued: "La Follette is the opposite of a demagogue. Capable of fierce invective, his oratory is impersonal; passionate and emotional himself, his speeches are temperate. Some of them are so loaded with facts and such closely knit arguments that they demand careful reading, and their effect is traced to his delivery, which is forceful, emphatic, and fascinating."

La Follette supported Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 presidential election and approved his social justice legislation. However, he complained that he was under the control of big business and was totally opposed to Wilson's decision to enter the First World War. Once war was declared La Follette opposed conscription and the passing of the Espionage Act. La Follette was accused of treason but was a popular hero with the anti-war movement.

Lincoln Steffens was a great supporter of La Follette: "Governor La Follette was a powerful man, who, short but solid, swift and willful in motion, in speech, in decision, gave the impression of a tall, a big man... what I saw at my first sight of him was a sincere, ardent man who, whether standing, sitting, or in motion, but the grace of trained strength, both physical and mental... Rather short in stature, but broad and strong, he had the gift of muscled, nervous power, he kept himself in training all his life. His sincerity, his integrity, his complete devotion to his ideal, were indubitable; no one who heard could suspect his singleness of purpose or his courage."

La Follette became the candidate of the Progressive Party in the 1924 presidential election. Although he gained support from trade unions, individuals like Fiorello La Guardia and Vito Marcantonio, the Socialist Party and the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, La Follette and his running partner, Burton K. Wheeler, only won one-sixth of the votes.

Robert M. La Follette died on 18th June, 1925.

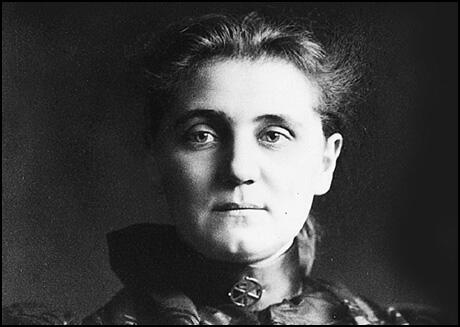

On this day in 1888 Jane Addams described visiting Toynbee Hall in London. "It is a community for University men who live there, have their recreation and clubs and society all among the poor people, yet in the same style they would live in their own circle. It is so free from 'professional doing good', so unaffectedly sincere and so productive of good results in its classes and libraries so that it seems perfectly ideal."

In 1884 an article by Samuel Augustus Barnett in the Nineteenth Century Magazine he suggested the idea of university settlements. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University could work among, and improve the lives of the poor during their holidays. According to Barnett, the role of the students was "to learn as much as to teach; to receive as much to give". This article resulted in the formation of the University Settlements Association.

Later that year Barnett and his wife, Henrietta Barnett, established Toynbee Hall, Britain's first university settlement. It was named after their friend and social reformer, Arnold Toynbee, who had died when he was only thirty years old. Most residents held down jobs in the City, or were doing vocational training, and so gave up their weekends and evenings to do relief work. This work ranged from visiting the poor and providing free legal aid to running clubs for boys and holding University Extension lectures and debates; the work was not just about helping people practically, it was also about giving them the kinds of things that people in richer areas took for granted, such as the opportunity to continue their education past the school leaving age. As Seth Koven has pointed out: "Settlements, as first envisioned by the Barnetts, were residential colonies of university men in the slums intended to serve both as centres of education, recreation, and community life for the local poor and as outposts for social work, social scientific investigation, and cross-class friendships between élites and their poor neighbours."

Toynbee Hall served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London. Other individuals who worked at Toynbee Hall include Richard Tawney, Clement Attlee, Alfred Milner, William Beveridge, Beatrice Webb and Robert Morant. Other visitors included Guglielmo Marconi who held one of his earliest experiments in radio there, and Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, was so impressed by the mixing and working together of so many people from different nations that it inspired him to establish the games. Georges Clemenceau visited Toynbee Hall in 1884 and claimed that Barnett was one of the "three really great men" he had met in England.

Charles Robert Ashbee, one of the people involved in the Arts and Crafts Movement, was a resident in 1888, as was Hubert Llewellyn-Smith, who went on to run New Survey of London Life and Labour for the London School of Economics in the 1930s. The Whitechapel Gallery had its roots in the art exhibitions held originally in the St. Jude's school rooms. These exhibitions were intended to bring the art of major galleries to the people of the East End. The 1926 General Strike came to an end at Toynbee Hall - the employers and the union leaders met there to discuss their terms.

In 1888 Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr visited Toynbee Hall and were so impressed with what they saw that the returned to the United States and established a similar project, Hull House, in Chicago. The Settlement Movement grew rapidly both in Britain, the United States and the rest of the world. The settlements and social action centres work together through the International Federation of Settlements.

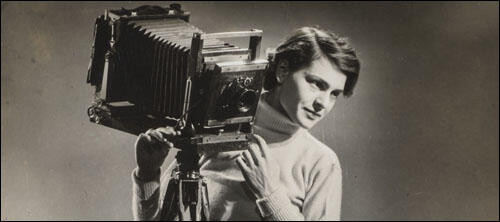

On this day in 1904 photographer Margaret Bourke-White was born in New York City. She became interested in photography while studying at Cornell University. After studying photography under Clarence White at Columbia University she opened a studio in Cleveland where she specialized in architectural photography.

In 1929 Bourke-White was recruited by Henry Luce as staff photographer for Fortune Magazine. She made several trips to the Soviet Union and in 1931 published Eyes on Russia. Deeply influence by the impact of the Depression, she became increasingly interested in politics. In 1936 Bourke-White joined Life Magazine and her photograph of the Fort Peck Dam appeared on its first front-cover.

In 1937 Bourke-White worked with the best-selling novelist, Erskine Caldwell, on the book You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). The book was later criticised for its left-wing bias and upset whites in the Deep South with its passionate attack on racism. Carl Mydans of Life Magazine later said that: "Margaret Bourke-White's social awareness was clear and obvious. All the editors at the magazine were aware of her commitment to social causes."

With other left-wing artists such as Stuart Davis, Rockwell Kent, and William Gropper, Bourke-White was a member of the American Artists' Congress. The group supported state-funding of the arts, fought discrimination against African American artists, and supported artists fighting against fascism in Europe. Bourke-White also subscribed to the Daily Worker and was a member of several Communist Party front organizations such as the American League for Peace and Democracy and the American Youth Congress

Bourke-White married Erskine Caldwell in 1939 and the couple were the only foreign journalists in the Soviet Union when the German Army invaded in 1941. Bourke-White and Caldwell returned to the United States where they produced another attack on social inequality, Say Is This the USA? (1942).

During the Second World War Bourke-White served as a war correspondent, working for both Life Magazine and the U.S. Air Force. Bourke-White, who survived a torpedo attack while on a ship to North Africa, was with United States troops when they reached the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

After the war Bourke-White continued her interest in racial inequality by documenting Gandhi's non-violent campaign in India and apartheid in South Africa.

The FBI had been collecting information on Bourke-White's political activities since the 1930s and in the 1950s became a target for Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee. However, a statement reaffirming her belief in democracy and her opposition to dictatorship of the left or of the right, enabled her to avoid being cross-examined by the committee.

Bourke-White also covered the Korean War where she took what she considered was her best ever photograph. This was of a meeting between a returning soldier and his mother, who thought he had been killed several months earlier.

In 1952 Bourke-White was discovered to be suffering from Parkinson's Disease. Unable to take photographs, she spent eight years writing her autobiography, Portrait of Myself (1963). Margaret Bourke-White died at Darien, Connecticut, on 27th August, 1971.

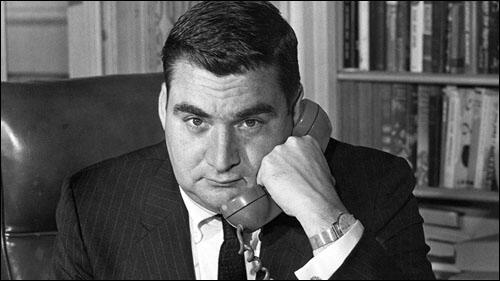

On this day in 1925 Pierre Salinger, the son of a German mining engineer, was born in San Francisco on 14th June, 1925. His mother was a French journalist. After completing his degree at the University of San Francisco he began work as an investigative journalist with the San Francisco Chronicle.

A member of the Democratic Party he was an active supporter of Harry Truman in the 1948 Presidential Election. It was while working for the Senate Committee on the Improper Activities in Labour and Management in 1957 that he met Robert Kennedy. He joined the Kennedy inner-circle and in 1960 John F. Kennedy appointed Salinger as his press secretary. He held the post until the assassination of the president. He agreed to stay on under Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1964 Salinger was appointed to the Senate after the death of Clair Engle of California. He served for only 148 days as he was defeating in the subsequent election. He remained active in politics and helped Robert Kennedy in his bid to become president in 1968. After Kennedy's assassination he moved to France where he worked for L'Express. This was followed by work as ABC's Paris Bureau Chief. In 1983 ABC moved to London as the network's chief foreign correspondent.

Salinger was the author of several books including With Kennedy (1966), For the Eyes of the President Only (1971), America Held Hostage: The Secret Negotiations (1983), The Dossier (1984), Above Paris (1985), Mortal Games (1989), Secret Dossier: The Hidden Agenda Behind the Gulf War (1991), An Honorable Profession: A Tribute to Robert F. Kennedy (1993), A Memoir (1995) and John F.Kennedy, Commander-in-chief (1997).

Pierre Salinger died on 16th October, 2004.

On this day in 1928 Emmeline Pankhurst died in a nursing home in Hampstead on 14th June, 1928, a month short of her seventieth birthday.

In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst established the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Emmeline stated that the main aim of the organisation was to recruit working class women into the struggle for the vote. "We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from ant party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto."

Some early members included Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst, Adela Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Elizabeth Robins, Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney, Mary Gawthorpe, May Billinghurst, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Mary Allen, Winifred Batho, Mary Leigh, Mary Richardson, Ethel Smyth, Teresa Billington-Greig, Helen Crawfurd, Emily Davison, Charlotte Despard, Mary Clarke, Margaret Haig Thomas, Cicely Hamilton, Eveline Haverfield, Edith How-Martyn, Constance Lytton, Kitty Marion, Dora Marsden, Hannah Mitchell, Margaret Nevinson, Evelyn Sharp, Nellie Martel, Helen Fraser, Minnie Baldock and Octavia Wilberforce.

The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic suggested, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS."

The forming of the WSPU upset both the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the Labour Party, the only party at the time that supported universal suffrage. They pointed out that in 1903 only a third of men had the vote in parliamentary elections. On the 16th December 1904, The Clarion published a letter from Ada Nield Chew, attacking WSPU policy: "The entire class of wealthy women would be enfranchised, that the great body of working women, married or single, would be voteless still, and that to give wealthy women a vote would mean that they, voting naturally in their own interests, would help to swamp the vote of the enlightened working man, who is trying to get Labour men into Parliament."

Teresa Billington Greig found Emmeline Pankhurst a difficult colleague: "To work alongside of her day by day was to run the risk of losing yourself. She was ruthless in using the followers she gathered around her, as she was ruthless to herself. She took advantage of both their strengths and their weaknesses suffered with you and for you while she believed she was shaping you and used every device of suppression when the revolt against the shaping came. She was a most astute statesman, a skilled politician, a self-dedicated reshaper of the world - and a dictator without mercy".

Emmeline Pankhurst was an impressive orator: "The crowd came - packing the hall to overflowing. The rowdy youths came. And one other factor I had scarcely fully reckoned upon came - Mrs. Pankhurst. She held that audience in the hollow of her hand. When a youth interrupted she turned and dealt with him, silenced him, and, without faltering in the thread of her speech, used him as an illustration of an argument. The audience was so intent to hear every word that even when one little group of youths let out that aforementioned evil-smelling gas it did no more than cause a faint stir in one small corner of the hall. As Mrs. Pankhurst continued the interruptions got fewer and fewer, and at last ceased altogether. Even when at the end came question-time, members of the audience were uncommonly chary of delivering themselves into her hands. That meeting was a revelation of the power of a great speaker."

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. It seemed certain that the Liberal Party would form the next government. Therefore, the WSPU decided to target leading figures in the party.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were both arrested.

Christabel Pankhurst was charged with assaulting the police and Annie Kenney with obstruction. They were both found guilty. Pankhurst was fined ten shillings or a jail sentence of one week. Kenney was fined five shillings, with an alternative of three days in prison. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote.

Emmeline Pankhurst was very pleased with the publicity achieved by the two women. "The comments of the press were almost unanimously bitter. Ignoring the perfectly well-established fact that men in every political meeting ask questions and demand answers of the speakers, the newspapers treated the action of the two girls as something quite unprecedented and outrageous... Newspapers which had heretofore ignored the whole subject now hinted that while they had formerly been in favour of women's suffrage, they could no longer countenance it."

In the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party won 399 seats and gave them a large majority over the Conservative Party (156) and the Labour Party (29). Pankhurst hoped that Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the new prime minister, and his Liberal government, would give women the vote. However, several Liberal MPs were strongly against this. It was pointed out that there were a million more adult women than men in Britain. It was suggested that women would vote not as citizens but as women and would "swamp men with their votes".

Campbell-Bannerman gave his personal support to Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), though he warned them that he could not persuade his colleagues to support the legislation that would make their aspiration a reality. Despite the unwillingness of the Liberal government to introduce legislation, Fawcett remained committed to the use of constitutional methods to gain votes for women. However, Pankhurst took a very different view.

On 23rd October, 1906, Emmeline Pankhurst organised a huge rally in Caxton Hall, and a deputation went to the House of Commons to demand the vote: She later wrote about this in her autobiography, My Own Story (1914): "Those women had followed me to the House of Commons. They had defied the police. They were awake at last thev were prepared to do something that women had never done before - fight for themselves. Women had always fought for men, and for their children. Now they were ready to light for their own human rights. Our militant movement was established.''

To coincide with the opening of parliament on 13th February 1907 the WSPU organized the first Women's Parliament at Caxton Hall. The women were confronted by mounted police. Fifty-eight women appeared in court as a result of the conflict. Most of those arrested received seven to fourteen days in Holloway Prison, though Sylvia Pankhurst and Charlotte Despard got three weeks.

Some leading members of the Women's Social and Political Union began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

In February, 1908, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and was sentenced to six weeks in prison. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause (2003), explained how she reacted to the situation: "Emmeline knew what to expect - she had by then heard graphic descriptions of prison life from Sylvia and Adela as well as from Christabel. She was shocked, though, when the wardress asked her to undress in order to put on her prison uniform - stained underwear, rough brown and red striped stockings and a dress with arrows on it. She was given coarse but clean sheets, a towel, a mug of cold cocoa and a thick slice of brown bread, and taken to her cell. Second division prisoners were kept in solitary confinement and were let out of their cells only for an hour's exercise each day. They were not allowed to receive letters for four weeks. Even though she had prepared herself for the experience, the reality hit her harder than she had anticipated."

On 25th June 1909, Marion Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her. According to Joseph Lennon: "She came to her prison cell as a militant suffragette, but also as a talented artist intent on challenging contemporary images of women. After she had fasted for ninety-one hours in London’s Holloway Prison, the Home Office ordered her unconditional release on July 8, 1909, as her health, already weak, began to fail".

On 22nd September 1909 Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Leigh were arrested while disrupting a public meeting being held by Herbert Asquith. Marsh, Ainsworth and Leigh were all sentenced to two weeks' imprisonment. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

Mary Leigh, described what it was like to be force-fed: "On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful - the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down - about a pint of milk... egg and milk is sometimes used." Leigh's graphic account of the horrors of forcible feeding was published while she was still in prison. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her.

Hunger-strikes now became the accepted strategy of the WSPU. In one eighteen month period, Emmeline Pankhurst endured ten hunger-strikes. She later recalled: "Hunger-striking reduces a prisoner's weight very quickly, but thirst-striking reduces weight so alarmingly fast that prison doctors were at first thrown into absolute panic of fright. Later they became somewhat hardened, but even now they regard the thirst-strike with terror. I am not sure that I can convey to the reader the effect of days spent without a single drop of water taken into the system. The body cannot endure loss of moisture. It cries out in protest with every nerve. The muscles waste, the skin becomes shrunken and flabby, the facial appearance alters horribly, all these outward symptoms being eloquent of the acute suffering of the entire physical being. Every natural function is, of course, suspended, and the poisons which are unable to pass out of the body are retained and absorbed."

In January 1910, Herbert Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement".

Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett both agreed to the idea and the WSPU declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated."

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, before they completed the task, Asquith called another election in order to get a clear majority. However, the result was very similar and Asquith still had to rely on the support of the Labour Party to govern the country.

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. Asquith made a speech where he made it clear that he intended to shelve the Conciliation Bill.

On hearing the news, Emmeline Pankhurst, led 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons on 18th November, 1910. Sylvia Pankhurst was one of the women who took part in the protest and experienced the violent way the police dealt with the women: "I saw Ada Wright knocked down a dozen times in succession. A tall man with a silk hat fought to protect her as she lay on the ground, but a group of policemen thrust him away, seized her again, hurled her into the crowd and felled her again as she turned. Later I saw her lying against the wall of the House of Lords, with a group of anxious women kneeling round her. Two girls with linked arms were being dragged about by two uniformed policemen. One of a group of officers in plain clothes ran up and kicked one of the girls, whilst the others laughed and jeered at her."

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel."

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct."

A new Conciliation Bill was passed by the House of Commons on 5th May 1911 with a majority of 167. The main opposition came from Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, who saw it as being "anti-democratic". He argued "Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife."

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he had told his close associates, such as Charles Masterman, the Liberal MP in West Ham North: "He (David Lloyd George) was very much disturbed about the Conciliation Bill, of which he highly disapproved although he is a universal suffragist... We had promised a week (or more) for its full discussion. Again and again he cursed that promise. He could not see how we could get out of it, yet he regarded it as fatal (if passed)."

Lloyd George was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Herbert Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill."

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose."

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament.

On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians, Herbert Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged."

The following month Millicent Fawcett wrote to her sister, Elizabeth Garrett: "We have the best chance of Women's Suffrage next session that we have ever had, by far, if it is not destroyed by disgusting masses of people by revolutionary violence." Elizabeth agreed and replied: "I am quite with you about the WSPU. I think they are quite wrong. I wrote to Miss Pankhurst... I have now told her I can go no more with them."

Henry Brailsford went to see the Emmeline Pankhurst and asked her to control her members in order to get the legislation passed by Parliament. She replied "I wish I had never heard of that abominable Conciliation Bill!" and Christabel Pankhurst called for more militant actions. The Conciliation Bill was debated in March 1912, and was defeated by 14 votes. Asquith claimed that the reason why his government did not back the issue was because they were committed to a full franchise reform bill. However, he never kept his promise and a new bill never appeared before Parliament.

Some members of the WSPU, including Adela Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence as a strategy. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU in October 1911. Sylvia Pankhurst was also critical of this new militancy.

Margery Corbett was a member of the NUWSS when she met Emmeline and Sylvia in 1911. "I talked to Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Sylvia. I admired their wonderful courage, but when they started hurting other people, I had to decide whether I wanted to go on working with the constitutional movement, or whether I would join the militants. Eventually I decided to remain a constitutional."

In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

Emmeline Pankhurst was one of those arrested. Once again she went on hunger strike: "I generally suffer most on the second day. After that there is no very desperate craving for food. weakness and mental depression take its place. Great disturbances of digestion divert the desire for food to a longing for relief from pain. Often there is intense headache, with fits of dizziness, or slight delirium. Complete exhaustion and a feeling of isolation from earth mark the final stages of the ordeal. Recovery is often protracted, and entire recovery of normal health is sometimes discouragingly slow." After she was released from prison she was nursed by Catherine Pine.

Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

One of the first arsonists was Mary Richardson. She later recalled the first time she set fire to a building: "I took the things from her and went on to the mansion. The putty of one of the ground-floor windows was old and broke away easily, and I had soon knocked out a large pane of the glass. When I climbed inside into the blackness it was a horrible moment. The place was frighteningly strange and pitch dark, smelling of damp and decay... A ghastly fear took possession of me; and, when my face wiped against a cobweb, I was momentarily stiff with fright. But I knew how to lay a fire - I had built many a camp fire in my young days -a nd that part of the work was simple and quickly done. I poured the inflammable liquid over everything; then I made a long fuse of twisted cotton wool, soaking that too as I unwound it and slowly made my way back to the window at which I had entered."

Sylvia Pankhurst was also very unhappy that the WSPU had abandoned its earlier commitment to socialism and disagreed with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise. She made the final break with the WSPU when the movement adopted a policy of widespread arson. Sylvia now concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London.

Emmeline was now estranged from two of her daughters. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote to Sylvia Pankhurst about her mother: "I believe she conceived her objective in the spirit of generous enthusiasm. In the end it obsessed her like a passion and she completely identified her own career with it in order to obtain it. She threw scruple, affection, honour, legality and her own principles to the winds."

In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses".

The women responsible for these arson attacks were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act.

On 24th February 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested for procuring and inciting persons to commit offences contrary to the Malicious Injuries to Property Act 1861. The Times reported: "Mrs Pankhurst, who conducted her own defence, was found guilty, with a strong recommendation to mercy, and Mr Justice Lush sentenced her to three years' penal servitude. She had previously declared her intention to resist strenuously the prison treatment until she was released. A scene of uproar followed the passing of the sentence."

After going nine days without eating, they released her for fifteen days so she could recover her health. "They sent me away, sitting bolt upright in a cab, unmindful of the fact that I was in a dangerous condition of weakness, having lost two stone in weight and suffered seriously from irregularities of heart action." On 26th May, 1913, when Emmeline Pankhurst attempted to attend a meeting, she was arrested and returned to prison.

In June, 1913, at the most important race of the year, the Derby, Emily Davison ran out on the course and attempted to grab the bridle of Anmer, a horse owned by King George V. The horse hit Emily and the impact fractured her skull and she died without regaining consciousness. Although many suffragettes endangered their lives by hunger strikes, Emily Davison was the only one who deliberately risked death. However, her actions did not have the desired impact on the general public. They appeared to be more concerned with the health of the horse and jockey and Davison was condemned as a mentally ill fanatic.

During this period Kitty Marion was the leading figure in the WSPU arson campaign and she was responsible for setting fire to Levetleigh House at St Leonards (April 1913), the Grandstand at Hurst Park racecourse (June 1913) and various houses in Liverpool (August, 1913) and Manchester (November, 1913). These incidents resulted in a series of further terms of imprisonment during which force-feeding occurred followed by release under the Cat & Mouse Act. It has been calculated that Marion endured 200 force-feedings in prison while on hunger strike.

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral."

Anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans". Another article on the Union of Democratic Control carried the headline: "Norman Angell: Is He Working for Germany?" Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield were described as "Bolshevik women trade union leaders" and Arthur Henderson, who was in favour of a negotiated peace with Germany, was accused of being in the pay of the Central Powers. Her daughter, Sylvia Pankhurst, who was now a member of the Labour Party, accused her mother of abandoning the pacifist views of Richard Pankhurst.

Adela Pankhurst also disagreed with her mother and in Australia she joined the campaign against the First World War. Adela believed that her actions were true to her father's belief in international socialism. She wrote to Sylvia that like her she was "carrying out her father's work". Emmeline Pankhurst completely rejected this approach and told Sylvia that she was "ashamed to know where you and Adela stand." Sylvia commented: "Families which remain on unruffled terms, though their members are in opposing political parties, take their politics less keenly to heart than we Pankhursts."

In 1917 Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst formed The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire."

The Women's Party also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions. In December 1918, Christabel was defeated in the general election at Smethwick.

After the First World War Emmeline spent several years in the USA and Canada lecturing for the National Council for Combating Venereal Disease, as a campaigner in a moral crusade against promiscuity. She was accompanied by her old friend, Catherine Pine. "The work suited her - it took her back on the road, on to the series of platforms with which her life had become synonymous."

When Emmeline returned to Britain in 1925 she joined the Conservative Party and was adopted as one of their candidates in the East End of London. Henry Snell commented "she found her appropriate spiritual home, and ended her days in the Tory Party, which used her to oppose Labour candidates and others whose help she had accepted, and on whose shoulders she had climbed to fame". Sylvia Pankhurst, who still held her strong socialist views, was appalled by this decision. Emmeline's was also angry with Sylvia for having an illegitimate baby and refused to see her daughter or grandson.

Adela Pankhurst, who had married Tom Walsh during the First World War, had five children - Richard named after her father, Sylvia after her sister, Christian, Ursula and Faith, who died soon after she was born. Emmeline never saw any of Adela's children. However, Adela, like her mother, had moved sharply to the right in the 1920s and she did write to her expressing regret for the long rift between them.

Emmeline, Christabel Pankhurst and Mabel Tuke decided to run a tea-shop on the French Riviera in 1925. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "In 1925 Mabel Tuke took part with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, in the ill-fated scheme to run a tea-shop at Jules-les-Pins on the French Riviera. Mrs Tuke provided most of the capital and did the baking." The venture was unsuccessful and they returned to England in the spring of 1926.

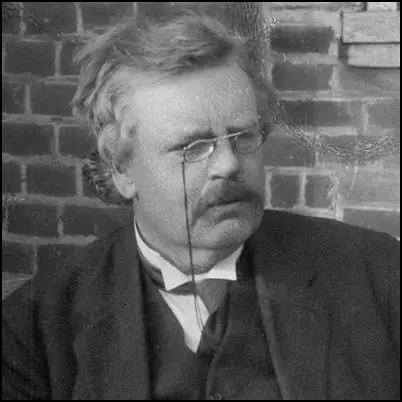

On this day in 1936 Gilbert Keith Chesterton ded.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, the elder son of Edward Chesterton and his wife, Marie Louise Grosjean, was born on 29th May 1874 at 32 Sheffield Terrace, Campden Hill, London. His father was an estate agent.

According to his biographer, Bernard Bergonzi, when his younger brother, Cecil Chesterton, was born, he "greeted his arrival with the satisfied response that now he would have someone to argue with, and the brothers went on cheerfully arguing throughout their lives, though Cecil had the more sharply polemical temperament."

Chesterton later recalled in his autobiography that he was a slow developer, not speaking until he was nearly three, and not reading until he was eight. There were plenty of books in the house and he became a passionate reader. He admitted that he had a sheltered and happy childhood in a comfortable middle-class home, where his interests in art and literature were encouraged by his parents. Chesterton was sent to St. Paul's School. Although he was an intelligent child he found it difficult to concentrate on subjects that did not interest him. He became a member of the debating society and it was the start of a life-long interest in politics. After leaving school he attended Slade Art School. At the time he thought of making a career in art, but soon found that his real gifts and inclination were for writing.

In 1895 he left art school and found work as a publisher's reader. Eventually he found work as a journalist. Like his father he was a supporter of the Liberal Party and began writing a regular column for the The Daily News. He also had articles published in Illustrated London News and The Bookman. Chesterton's first two books were collections of poetry, The Wild Knight (1900) and Greybeards at Play (1900).

Chesterton was commissioned to write a study of the poet Robert Browning. The book was published in 1903. Bernard Bergonzi has pointed out: "That he was invited to write it while still only in his twenties was a sign of his growing celebrity. The book was well received by ordinary readers but not by Browning experts, who objected to its biographical inaccuracies and frequent misquotations. Chesterton was habitually careless about questions of fact, but Robert Browning contains acute discussions of Browning's poetry; among many other things, Chesterton was an excellent literary critic. Nevertheless, the book's real interest is the extent to which he identifies with his subject, and the clues it offers to his later development. When he wrote it he was more than a young man embarking on a successful literary career. He was also engaged in a personal struggle to make sense of the world, a struggle which marked all his writing."

His brother, Cecil Chesterton, had been a socialist and a member of the Fabian Society.Meanwhile, G. K. Chesterton and his great friend, Hilaire Belloc, became supporters of Distributism, a theory based upon the principles of Catholic social teaching, especially the teachings of Pope Leo XIII and was seen as a philosophy that was opposed to both socialism and capitalism. It has been claimed that it expressed similar ideas to the anarchism of Prince Peter Kropotkin.

Gilbert Chesterton later attempted to explain the changes in his brother's political beliefs: "Thus he came to suspect that Socialism was merely social reform, and that social reform was merely slavery. But the point still is that though his attitude to it was now one of revolt, it was anything but a mere revulsion of feeling. He did, indeed, fall back on fundamental things, on a fury at the oppression of the poor, on a pity for slaves, and especially for contented slaves. But it is the mark of his type of mind that he did not abandon Socialism without a rational case against it.... The theory he substituted for Socialism is that which may for convenience be called Distributivism; the theory that private property is proper to every private citizen. This is no place for its exposition; but it will be evident that such a conversion brings the convert into touch with much older traditions of human freedom, as expressed in the family or the guild. And it was about the same time that, having for some time held an Anglo-Catholic position, he joined the Roman Catholic Church."

In 1911 the two brothers and Hilaire Belloc launched the political weekly, the Eye-Witness. With contributors such as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Arthur Ransome and Maurice Baring, the journal sold over 100,000 copies a week. It also concentrated on exposing examples of political corruption, including the sale of peerages. Chesterton also published the popular novel, The Innocence of Father Brown (1911). Bernard Bergonzi points out: "Here he introduces one of the most famous of literary detectives, the insignificant-seeming little Roman Catholic priest, Father Brown, who is possessed of formidable powers of observation and ratiocination, and whose work as a confessor has given him a deep insight into human nature and the criminal mentality in particular."

In 1912 Cecil Chesterton, backed by money from his father, took over the paper. The name was changed to the New Witness and Ada Jones became assistant editor. It now concentrated on exposing examples of political corruption, including the sale of peerages. The journal also accused David Lloyd George, Herbert Samuel and Rufus Isaacs of corruption. It was suggested that the men had profited by buying shares based on knowledge of a government contract granted to the Marconi Company to build a chain of wireless stations.

In January 1913 a parliamentary inquiry was held into the claims made by New Witness. It was discovered that Isaacs had purchased 10,000 £2 shares in Marconi and immediately resold 1,000 of these to Lloyd George. Although the parliamentary inquiry revealed that Lloyd George, Samuel and Isaacs had profited directly from the policies of the government, it was decided the men had not been guilty of corruption. Godfrey Isaacs, the financier who headed the company, sued Chesterton and after being found guilty was fined £100.

On the outbreak of the First World War Chesterton became fiercely patriotic. He was willingly recruited by Charles Masterman, the head of Britain's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), to help shape public opinion. His work included the writing of two pamphlets, The Barbarism in Berlin (1915) and The Crimes of England (1915) and numerous articles in Britain's newspapers.

Cecil Chesterton joined the East Surrey Regiment. While on leave in 1917 Ada Jones eventually agreed to marry Chesterton. Her biographer, Mark Knight, pointed out: "After rejecting his marriage proposals for many years she eventually agreed to marry him when he was enlisted as a private during the First World War. They married on 9 June 1917 at two ceremonies, the first at a register office in London and the second at Corpus Christi Church in Maiden Lane, London."

Cecil survived the war only to be taken seriously ill with nephritis shortly after the armistice and died on 6th December, 1918. Gilbert Keith Chesterton commented: "My brother, died in a French military hospital of the effects of exposure in the last fierce fighting that broke the Prussian power over Christendom; fighting for which he had volunteered after being invalided home. Any notes I can jot down about him must necessarily seem jerky and incongruous; for in such a relation memory is a medley of generalisation and detail, not to be uttered in words."

After the death of his brother he vowed to continue the pubication of the New Witness. In 1925 it was renamed GK's Weekly. Some of his friends "claimed that it made heavy demands on him for both money, to keep it afloat, and time, since he wrote much of its content himself". In 1922 Chesterton became a Roman Catholic. This influenced the subject matter of his work and he published biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St Thomas Aquinas.

On this day in 1940 Sonia Tomara writes about the German invasion of France.

For four days and four nights I have shared the appalling hardship of 5,000,000 French refugees who are now fleeing down all the roads of France leading to the south. My story is the typical story of nine-tenths of these refugees.

I left Paris Monday night, June 10, in a big car which was to take me, my sister, Irene Tomara, and a Canadian doctor, William Douglas, who has been working with the American and civilian refugees. We loaded our car with whatever we could carry. We had enough gasoline to take us at least to Bordeaux. It was quite dark when we left. All days cars had been going toward the southern gates of Paris. Just as we departed dark clouds rose above the town, obscuring the rising crescent of the moon. I thought at first it was a storm. Then I understood it was a smoke screen the French had laid down to save the city from bombing.

We drove across the Seine bridge and in complete darkness past the Montparnasse station, in which a desperate crowd was camping. We found the so-called Italian Gate and drove past it, risking all the time the chance of being hit by trucks. But all went well for about fifteen miles. Then, as we started up the first hill, the gears of our car refused to work and the car would not move.

We managed to pull off the road and park. We were in a small suburb of Paris. As nothing could be done during the dark hours, we rolled into our sleeping bags in a ditch alongside the road and tried to sleep. But cars roared by us incessantly. Then came an air-raid alarm. Then the cars started again.

When dawn came we tried to get the car going. It would not start. We waited for hours for a mechanic, while cars passed at the rate of twenty a minute. Then we learned there were no mechanics. They had all been called into the army. But the driver of a truck stopped and inspected the car. He said it could not be repaired on the road.

We tried to buy a little truck that could take our luggage. Finally the gendarmes on the road took pity on us and stopped a military truck, asking its driver to tow us. Fortunately we had a chain. We started off at noon on the road to Fontainebleau. At that time the road was a dense stream of army and factory trucks carrying big machines. We drove all day, and at 8 P.M. got into Fontainebleau.

In Fontainebleau we located a garage. The mechanic looked at the car and said it could not be repaired in less than two days. "We have no men to repair it, anyway," the manager of the garage said. "We work only for the army." We passed the night at a hotel and in the morning started to look for a truck that could tow us. Douglas found a youngster who had a country truck, but no gasoline. He was going back to Paris. We promised him gasoline and he said he would take us to Orleans and then drive to Paris.

We were abandoning our car, which was worth at least 40,000 francs (approximately $875), but money had ceased to have significance. We reloaded our bags on the truck, which had no top, and sat on them. It was 5 p.m. We drove five miles without difficulty and then got into a stream of refugees and army cars. Refugees blocked the road by trying to get past the main line of cars, thus interfering with oncoming traffic.

At 10 p.m. we had driven less than fifteen miles from Fontainebleau. The boy driving our car was in despair. He wanted to turn back to Paris, but we would not let him. We saw thousands of cars by the roadsides, without gasoline or broken down.

We drove on in the night. Presently the road cleared, but we were off our route. Soldiers had detoured traffic to permit movement of military cars. We were driving south instead of toward Orleans. In a small village we turned off and started at a good speed through the dead of night, with lights turned off. It was fantastic. The clouds parted and the moon came up. The country seemed phantom-like. There were piles of stones in front of each village we passed, and peasants

with rifles guarded these barricades. They looked at our papers and let us pass.

We arrived before the Orleans station at 3 a.m. on Thursday. After three nights and two days we had made only seventy miles. The scene near the station was appalling. People lay on the floor inside and the town square was filled. We piled our baggage and waited until daylight.

There was nothing to eat in the town, no rooms in the hotels, no cars for sale or hire, no gasoline anywhere. Yet a steady stream of refugees was coming in, men, women and children, all desperate, not knowing where to go or how.

I walked around and found a truck that was fairly empty. I talked to the driver, offering him money to take me to Tours. He would take us near Tours. For food, we had only a little wine, some stale bread and a can of ham.

The scene of the refugees around the station was the most horrible I had ever seen, worse than the refugees in Poland. Fortunately, there was no bombing. Had there been any attacks it would have been too ghastly for words. Children were crying. There was no milk, no bread. Yet social workers were doing their best and groups were led away all the time, but new ones continued to arrive.

All morning we sought means of transportation. There was none. I decided to go to Tours. I started to walk in the rain with my typewriter and sleeping bag, at last getting a lift in a car which moved slowly through a mob of refugees moving in the opposite direction. In Tours, I learned that the government had left. Also gone were most newspapermen, but a press wireless operator and the French censor were still there.

As I finish this story there is a German air raid. The sound of bombs is terrific. I hope the German bombers have not hit at the road which leads to the south, for there refugees are packed in fleeing crowds.

The catastrophe that has befallen France has no parallel in human history. Nobody knows how or when it will end. Like the other refugees, and there are millions of us, I do not know tonight when I shall sleep in a bed again, or how I shall get out of this town.

On this day in 1950 Katharine Glasier, died. Her home, Glen Cottage, in the village of Earby, where she lived from 1922 until her death on 14 June 1950, was preserved in her memory by the labour movement.

Katharine Conway, the daughter of the Samuel Conway and Amy Curling, was born on 25th September, 1867. Her father was a Congregational parson in Chipping Ongar, but when Katharine was a child the family moved to Walthamstow.

The Conways held progressive views and Katharine received an education equivalent to that of her brothers. After being educated at home by her mother until the age of ten, Katharine went to the Hackney Downs High School for Girls.

Amy Conway died in 1881 after giving birth to her seventh child. This was a devastating blow as Katharine was very close to her mother. She later told Ramsay MacDonald: "I was 12 when my mother died and until my father married again when I was nearly 16 I had no home happiness at all. His grief and loneliness put out the sunshine for us children. And the second wife was tenderly good to us."

At the age of nineteen, Katharine began her studies at Newnham College, Cambridge. At university Katharine came under the influence of the militant feminist, Helen Gladstone, the youngest daughter of Herbert Gladstone. Katharine also met Olive Schreiner, a woman who "encouraged every bit of courageous aspiration or rebellion she found in us." She finished her studies in 1889 and she was officially placed second in her College Tripos though Gladstone claimed she really come top. At that time Cambridge University did not grant woman degrees but for the rest of her life she always placed the initials B.A. after her name.

Katharine found work as a Classics mistress at Redland High School in Bristol. One Sunday in November, 1890, Katharine was on her way to church when she encountered a demonstration by low-paid women workers. Katharine asked the women about their problems and it was later claimed that it was the discussion with these women that converted her to socialism. Soon after this incident, Katharine joined the Bristol Socialist Society.

Most of the members of the Socialist Society were supporters of H. H. Hyndman and the Social Democratic Federation. Katharine found their views too revolutionary and left to join the Bristol Fabian Society. Uncomfortable with her position teaching at a selective school, Katharine resigned and took a job at a board school in St Philips, a working class district of Bristol.

Katherine was greatly influenced by Edward Carpenter's book England's Ideal (1887): "Edward Carpenter woke a new power of love and worship within me. It was as if in that smoke-laden room a great window had been flung wide open and the vision of a new world had been shown me: of the earth reborn to beauty and joy, the home, to use Edward Carpenter's own words, 'of a free people, proud in the mastery and divinity of their lives. As I went back to my Clifton lodgings, I vaguely realised that every value life had previously held for me had changed as by some mysterious spiritual alchemy. I was ashamed of the privileges and elaborate refinements of which I had previously been so proud; the joy of comradeship, the glory of life, lost and found in the 'agelong, peerless cause' had been revealed to me, dimming all others."

In 1891 the Fabian Society began to arrange for members to travel around the country giving lecturers on Socialism. At the Fabian meetings Katharine impressed local members with her ability to argue the case for socialism that that it was suggested that she should become a Fabian lecturer. Over the next few months Katharine attracted large crowds to hear her talk on subjects such as "Socialism and the Home", "The Religion of Socialism" and "Why Working Women Want the Vote?"

William De Matto commented: "It is possible that Katharine Conway was getting more applause than a woman less young and attractive might have got but that was all doing good to Socialism. She has a peculiar magnetic influence over her audiences, and larger audiences could be drawn for her than for almost any other lecturer."

At these meetings Katharine came into contact with important figures in the Fabian Society including Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Robert Blatchford. Shaw proposed marriage but Katharine told him that she intended dedicating her life to socialism. Katharine also met Edward Hulton, who recruited her to write for his radical newspaper, the Manchester Sunday Chronicle.

In the autumn of 1892 Katharine attended the Trades Union Congress (TUC) meeting in Glasgow. One of those who heard her speak was Bruce Glasier, one of the leaders of the socialist movement in Scotland. They quickly became close friends and married on 21st June, 1893. George Bernard Shaw sent his congratulations reminding Katherine of what he had previously said about marriage and children. Katherine wrote back explaining she did not intend to have any children. Shaw replied with a postcard: "Invite me to the christening."

Katharine Glasier continued to lecture on socialism but had become critical of the Fabian Society approach to political change. Katharine was a Christian Socialist who once said that to her, "socialism was the economic expression of Christianity". The recently formed, Independent Labour Party, was led by Christians such as James Keir Hardie, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett and Philip Snowden. In 1893 Katharine joined the ILP and it was not long before she became the only woman on the party's National Administrative Council.

When Katharine and Bruce married they agreed not to have children so that they could devote the rest of their lives to the socialist cause. However, in 1896 Bruce Glasier and Emmeline Pankhurst were charged with speaking at an illegal meeting. Katharine was with Emmeline when she returned home after being found not guilty. Katharine was later to say that it was seeing Harry Pankhurst embrace his mother after discovering that she was not to be sent to prison, that convinced her to have children. Her daughter, Jeannie, was born the following year.

Despite being a mother, Katharine Glasier continued to tour the country making speeches on socialism. In 1900 she lectured in over thirty different towns. Bruce Glasier was also in great demand as he had recently been elected as chairman of the Independent Labour Party.

Katharine continued to write and as well as having a regular column in the ILP newspaper The Labour Leader, she contributed to other socialist journals and newspapers such as The Labour Woman. Katharine also wrote a feminist novel, Marget: A Twentieth-Century Novel and Tales from the Derbyshire, a collection of short-stories.

Katharine was not active in the women's suffrage movement. She disagreed with the NUWSS policy of a limited women's suffrage bill and totally disapproved of the militant tactics used by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Like most members of the Independent Labour Party, Katharine supported the campaign for complete adult suffrage.

In 1916 Katharine Glasier became editor of the The Labour Leader. The anti-war stand that its previous editor, Fenner Brockway, took was continued. At first this caused sales to slump but this eventually attracted a larger readership from young people disillusioned by the war. By the summer of 1917 sales of the newspaper under Katharine's editorship, reached an all-time peak of 51,000. The Independent Labour Party was so pleased that they raised her salary from £2.17.0 to £3.5.0 a week. As editor she clashed with Philip Snowden over his anti-Bolshevik writings.