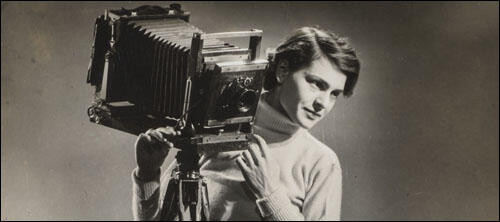

Margaret Bourke-White

Margaret Bourke-White was born in New York City on 14th June, 1904. She became interested in photography while studying at Cornell University. After studying photography under Clarence White at Columbia University she opened a studio in Cleveland where she specialized in architectural photography.

In 1929 Bourke-White was recruited by Henry Luce as staff photographer for Fortune Magazine. She made several trips to the Soviet Union and in 1931 published Eyes on Russia. Deeply influence by the impact of the Depression, she became increasingly interested in politics. In 1936 Bourke-White joined Life Magazine and her photograph of the Fort Peck Dam appeared on its first front-cover.

In 1937 Bourke-White worked with the best-selling novelist, Erskine Caldwell, on the book You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). The book was later criticised for its left-wing bias and upset whites in the Deep South with its passionate attack on racism. Carl Mydans of Life Magazine later said that: "Margaret Bourke-White's social awareness was clear and obvious. All the editors at the magazine were aware of her commitment to social causes."

With other left-wing artists such as Stuart Davis, Rockwell Kent, and William Gropper, Bourke-White was a member of the American Artists' Congress. The group supported state-funding of the arts, fought discrimination against African American artists, and supported artists fighting against fascism in Europe. Bourke-White also subscribed to the Daily Worker and was a member of several Communist Party front organizations such as the American League for Peace and Democracy and the American Youth Congress

Bourke-White married Erskine Caldwell in 1939 and the couple were the only foreign journalists in the Soviet Union when the German Army invaded in 1941. Bourke-White and Caldwell returned to the United States where they produced another attack on social inequality, Say Is This the USA? (1942).

During the Second World War Bourke-White served as a war correspondent, working for both Life Magazine and the U.S. Air Force. Bourke-White, who survived a torpedo attack while on a ship to North Africa, was with United States troops when they reached the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

After the war Bourke-White continued her interest in racial inequality by documenting Gandhi's non-violent campaign in India and apartheid in South Africa.

The FBI had been collecting information on Bourke-White's political activities since the 1930s and in the 1950s became a target for Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee. However, a statement reaffirming her belief in democracy and her opposition to dictatorship of the left or of the right, enabled her to avoid being cross-examined by the committee.

Bourke-White also covered the Korean War where she took what she considered was her best ever photograph. This was of a meeting between a returning soldier and his mother, who thought he had been killed several months earlier.

In 1952 Bourke-White was discovered to be suffering from Parkinson's Disease. Unable to take photographs, she spent eight years writing her autobiography, Portrait of Myself (1963).

Margaret Bourke-White died at Darien, Connecticut, on 27th August, 1971.

Primary Sources

(1) John Vassos, interviewed by Vicki Goldberg about his friendship with Margaret Bourke-White (3rd June, 1982)

I've never known a human being that had such a beautiful spirit. Like somebody with their open arms coming to you. There will never be another one like that again. She was a fabulous woman because of her terrific drive and energy. I never saw anything like it, never saw another person to equal that drive. It came out the minute you were in her presence, in her speech, in her moves.

(2) Margaret Bourke-White, Photographing This World, The Nation (19th February, 1936)

As the echoes of the old debate - is photography an art? - die away, a new and infinitely more important question arises. To what extent are photographers becoming aware of the social scene and how significantly are their photographs portraying it? The major control is the photographer's point of view. How alive is he? Does he know what is happening in the world? How sensitive has he become during the course of his own photographic development to the world-shaking changes in the social scene about him?

All creative workers will comprehend that in a large sense these problems apply to all workers whether they are building motor trucks, railroad trestles, power dams, or pictures. It is my own conviction that defense of the economic needs, as well as their liberty of artistic expression, will inevitably draw them closer to the struggle of the great masses of American people for security and the abundant life which they are more than anxious to earn by productive work.

(3) Erskine Caldwell, interviewed by Vicki Goldberg about working with Margaret Bourke-White on You Have Seen Their Faces (12th January, 1982)

She more or less relied upon me as a sort of official guide. But once she got there, the whole situation was in her hands. She was in charge of everything, manipulating people and telling them where to sit and where to look and what not. She was very adept at being able to direct people. She was almost like a motion picture director. Very astute in that respect. That's how she achieved such a good effect, I think, with her settings, and her people not so much staging it, but helping people be themselves.

(4) Archibald MacLeish, letter to Henry Luce (29th June, 1936)

The great revolution of journalism are not revolutions in public opinion, but revolutions in the way in which public opinion is formed. The greatest of these, a revolution greater even than of the printing press, is the revolution of the camera. But it is also a revolution which has not yet been brought to use. Magazines and newspapers have made use of photographs, but not in their own terms. Photographs have been used as illustrations, but the camera no longer illustrates. The camera tells. The camera shall take its place as the greatest and by all measurements the most convincing reporter of contemporary life.

(5) Margaret Bourke-White, radio interview (January, 1939)

It is my firm belief that democracy will not lose hold as long as people really know what is going on and the photographer has a very valuable part to do in showing what is going on. I believe that fascism could not have gained the lead it has in Europe if there had been a truly free press so that the great mass of people could have been informed and then could not have misled as they have been by false promises.

(6) Westbrook Pegler, a strong supporter of Joseph McCarthy, attacked the political beliefs of Margaret Bourke-White in his syndicated column on 4th September, 1951.

In the compendium of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Miss Bourke-White is cited thirteen times. Erskine Caldwell, himself cited twenty-two times in the compendium, has collaborated with her on three propaganda books, You Have Seen Their Faces, North of the Danube, and Say, is this the U.S.A.

(7) Margaret Bourke-White believed that the most important photograph she took in her career was of Churl Jin and his mother in South Korea. Churl Jin's mother believed her son had been killed in the Korean War.

In a whole lifetime of taking pictures, a photographer knows that the time will come when he will take one picture that seems the most important of all. You hope the sun will be shining, and that you will have a simple and significant and beautiful background. You pray there won't be any unwanted people staring into the lens. Most of all, you hope that the emotion you are trying to capture will be the real one, and will be reflected on the faces of the people you are photographing.