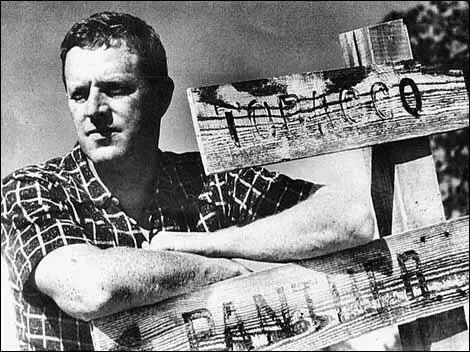

Erskine Caldwell

Erskine Caldwell, the son of a missionary, was born in Coweta, Georgia, on 17th December, 1903. As a child he travelled with his father and developed a concern for the poor. He was educated at the University of Virginia but did not graduate.

Caldwell moved to Maine in 1926 where he began writing for various journals including the New Masses and the Yale Review. He also published several novels but it was not until Tobacco Road (1932), a novel about the plight of poor sharecroppers, that critics began to take notice of his work. Dramatized by Jack Kirkland in 1933, it made American theatre history when it ran for over seven years on Broadway.

His next novel, God's Little Acre (1933) was also about poor whites living in the rural South. Both novels dealt with social injustice and many people objected to the impression it gave of America. When the New York Society for the Prevention of Vice tried to stop the book from being sold, Caldwell took the case to court and with the testimony of critics such as H. L. Mencken and Sherwood Anderson, won his case.

In 1936 Caldwell met and married the photographer, Margaret Bourke-White. They collaborated on You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), a documentary account of impoverished living conditions in the South. Other books by the couple included Russia at War (1942), North of the Danube (1975) and Say, is This the U.S.A.? (1977).

During the Second World War he worked as a newspaper reporter in the Soviet Union. An account of his experiences appeared in All Out on the Road to Smolensk (1942) and Call It Experience (1951). By the late 1940s Caldwell had sold more books than any author in America's history. God's Little Acre alone sold over fourteen million copies. His attacks on poverty, racism and the tenant farming system, had a significant impact on public opinion.

Caldwell wrote numerous short stories: collections include Jackpot (1940) and The Courting of Susie Brown (1952). Essays on his travels throughout the United States appeared in Around About America (1964) and Afternoons in Mid-America (1976).

Erskine Caldwell died in Arizona on 11th April, 1987.

Primary Sources

(1) Erskine Caldwell, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

Clinton, Louisiana: There are no landlords striding over their Mississippi Delta plantations cracking ten-foot braided-leather whips at their Negro sharecroppers' heels. At least there are only a few. Peonage, like lynching, is not condoned in theory; but conditions, usually best described as local, are sometimes called upon to justify it in practice. And when a plantation-owner feels the urge tp beat and whip and maul a Negro, there are generally several within sight or sound to chose from. Keeping a Negro constantly in physical bondage would be an unnecessary expense and chore; the threat of physical violence is enough.

(2) Erskine Caldwell, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

Magee, Mississippi: The white farmer has not always been the lazy, slipshod, good-for-nothing person that he is frequently described as being. Somewhere in his span of life he became frustrated. He felt defeated. He felt the despair and dejection that comes from defeat. He was made aware of the limitations of life imposed upon those unfortunate enough to be made slaves of sharecropping. Out of his predicament grew desperation, out of desperation grew resentment. His bitterness was a taste his tongue would always know.

In a land that has long been glorified in the supremacy of the white race, he directed his resentment against the black man. His normal instincts became perverted. He became wasteful and careless. He became bestial. He released his pent-up emotions by lynching the black man in order to witness the mental and physical suffering of another human being. He became cruel and inhuman in everyday life as his resentment and bitterness increased. He released his energy from day to day by beating mules and dogs, by whipping and kicking an animal into insensibility or to death. When his own suffering was more than he could stand, he could live only by witnessing the suffering of others.

(3) Erskine Caldwell, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

Peterson: Alabama: The house was dirty and disheveled. He and his wife no longer had any pride in their home or in their appearance. They went unwashed. He sat in the shade, his hat pulled over his eyes, and watched the spring come, the summers go. The older children struggled with cotton. It did not matter much to him then. He found a shack several miles away. He got the owner's permission to live in it on the promise of making the children work out the rent in the cottonfield.

The children, old and young, worked for the landlord to pay the rent on the shack. After that, one of them would find a day's work occasionally, and earn enough to buy cornmeal and molasses, sometimes meat. The shack was without a floor. There was only one bed. They lived in two rooms, the eight of them. The youngest child died of pneumonia. The two oldest boys left home one day and did not come back again.

(4) Erskine Caldwell, interview with a woman from Troy, Alabama, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

We've been here most of our lives, my husband and me, and I feel like I'm done for, and my husband looks it. If it wasn't for our boy, we just couldn't get any cotton raised to pay the rent. My husband is just no account. He sits there on the porch all day looking out across the road and don't pretend to move. My daughter is only half-bright, and can't do nothing much more than sweep a room, and she's not good at that. I've got body sickness and can't stand working in the fields any more, and it's all I can do to drag myself around the house and cook a little food. All I feel like doing most of the time is finding me a nice place to lay myself down in and die.

(5) Erskine Caldwell, interview with a bank manager, Augusta, Georgia, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937)

Don't ask me whose fault it is. I don't know. I don't even know anybody who thinks he knows. All I know is that one man out of ten makes a living, and more, out of cotton, and the other nine poor devils get the short end of the stick. It's my business to sit here in the bank and make it a rule to be in when that one farmer shows up to borrow money, and to be out when the other nine show up. Some nights I can't sleep at all for lying awake wondering what's going to happen to all those losing tenant farmers. A lot of them are hungry, ragged, and sick. Everybody knows about it, but nobody does anything about it. If the government doesn't do something about the losing cotton farmers, we'd be doing them a favor to go out and shot them out of their misery.