Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler was born in about 1340. One document suggested that as a young man he lived in Colchester. It has been suggested that during this time he became a follower of John Ball. There is some evidence that he fought in the Hundred Years War and worked for Richard Lyons, one of the sergeant-at-arms of Edward III. By the 1370s Tyler was living in Maidstone. (1)

In 1379 Richard II called a parliament to raise money to pay for the continuing war against the French. After much debate it was decided to impose another poll tax. This time it was to be a graduated tax, which meant that the richer you were, the more tax you paid. For example, the Duke of Lancaster and the Archbishop of Canterbury had to pay £6.13s.4d., the Bishop of London, 80 shillings, wealthy merchants, 20 shillings, but peasants were only charged 4d.

1380 Poll Tax

The proceeds of the 1379 tax was quickly spent on the war or absorbed by corruption. In 1380, Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, suggested a new poll tax of three groats (one shilling) per head over the age of fifteen. "There was a maximum payment of twenty shillings from men whose families and households numbered more than twenty, thus ensuring that the rich payed less than the poor. A shilling was a considerable sum for a working man, almost a week's wages. A family might include old persons past work and other dependents, and the head of the family became liable for one shilling on each of their 'polls'. This was basically a tax on the labouring classes." (2)

The peasants felt it was unfair that they should pay the same as the rich. They also did not feel that the tax was offering them any benefits. For example, the English government seemed to be unable to protect people living on the south coast from French raiders. Most peasants at this time only had an income of about one groat per week. This was especially a problem for large families. For many, the only way they could pay the tax was by selling their possessions. John Wycliffe gave a sermon where he argued: "Lords do wrong to poor men by unreasonable taxes... and they perish from hunger and thirst and cold, and their children also. And in this manner the lords eat and drink poor men's flesh and blood." (3)

According to John Stow, Tyler's fourteen-year-old daughter, Alice, was sexually assaulted by a tax-collector, when he was checking to see if she was old enough to pay the tax: "the mother hearing her daughter screech out, and seeing how in vain she struggled against him, being therefore grievously offended, she cried out also and leaving the house ran into the street among her neighbours, clamouuring about that there was one within that would ravish her daughter". (4)

When he heard the news, Wat Tyler hurried home and attacked the tax collector and gave him such a "knock upon the head that he broke his skull and his brains flew about the room. Tyler knew that he would be treated very harshly by the authorities. He therefore decided to become involved in the poll tax riots that were taking place all over Essex and Kent. Tyler now joined the main body of the rebels at Rochester. (5)

The Peasants' Revolt

It was not long before Wat Tyler emerged as the leader of the peasants. "His ability as leader, organizer and spokesman is clearly revealed throughout the revolt, while his standing among the rebel commons was proved by the immediate acceptance of his captaincy, not only in Kent and Essex, but in Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, and even farther afield; while the strength and vigour of his personality impressed itself even on the unwilling recorders of his work." (6) Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906) claims that the main reason that Wat Tyler became the leader of the revolt was because he was a man with military experience and knew how to establish authority over a mob. (7)

Wat Tyler's first decision was to march to Maidstone to free John Ball from prison. "John Ball had been set free and was safe among the commons of Kent, and he was bursting to pour out the passionate words which had been bottled up for three months, words which were exactly what his audience wanted to hear." (8) Dan Jones has argued that "Tyler and Ball in combination were a dangerous prospect: the captain and the prophet; military nous married to popular demagogy." (9)

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) has pointed out that it was very important for the peasants to be led by a religious figure: "For some twenty years he had wandered the country as a kind of Christian agitator, denouncing the rich and their exploitation of the poor, calling for social justice and freeman and a society based on fraternity and the equality of all people." John Ball was needed as their leader because alone of the rebels, he had access to the word of God. "John Ball quickly assumed his place as the theoretician of the rising and its spiritual father. Whatever the massess thought of the temporal Church, they all considered themselves to be good Catholics." (10)

On 5th June there was a revolt at Dartford and two days later Rochester Castle was taken. The peasants arrived in Canterbury on 10th June. Here they took over the archbishop's palace, destroyed legal documents and released prisoners from the town's prison. More and more peasants decided to take action. Manor houses were broken into and documents were destroyed. These records included the villeins' names, the rent they paid and the services they carried out. What had originally started as a protest against the poll tax now became an attempt to destroy the feudal system. (11)

The peasants decided to go to London to see Richard II. As the king was only fourteen-years-old, they blamed his advisers for the poll tax. The peasants hoped that once the king knew about their problems, he would do something to solve them. The rebels reached the outskirts of the city on 12 June. It has been estimated that approximately 30,000 peasants had marched to London. At Blackheath, John Ball gave one of his famous sermons on the need for "freedom and equality". (12)

Wat Tyler also spoke to the rebels. He told them: "Remember, we come not as thieves and robbers. We come seeking social justice." Henry Knighton records: "The rebels returned to the New Temple which belonged to the prior of Clerkenwell... and tore up with their axes all the church books, charters and records discovered in the chests and burnt them... One of the criminals chose a fine piece of silver and hid it in his lap; when his fellows saw him carrying it, they threw him, together with his prize, into the fire, saying they were lovers of truth and justice, not robbers and thieves." (13)

Charles Poulsen praises Wat Tyler as learning the "lessons of organisation and discipline" when in the army and in showing the "same pride in the customs and manners of his own class as the noblest baron would for his". (14) The medieval historians were less complimentary and Thomas Walsingham described him as a "cunning man, endowed with much sense if he had applied his intelligence to good purposes". (15)

Richard II gave orders for the peasants to be locked out of London. However, some Londoners who sympathised with the peasants arranged for the city gates to be left open. Jean Froissart claims that some 40,000 to 50,000 citizens, about half of the city's inhabitants, were ready to welcome the "True Commons". (16) When the rebels entered the city, the king and his advisers withdrew to the Tower of London. Many poor people living in London decided to join the rebellion. Together they began to destroy the property of the king's senior officials. They also freed the inmates of Marshalsea Prison. (17)

Part of the English Army was at sea bound for Portugal whereas the rest were with John of Gaunt in Scotland. (18) Thomas Walsingham tells us that the king was being protected in the Tower by "six hundred warlike men instructed in arms, brave men, and most experienced, and six hundred archers". Walsingham adds that they "all had so lost heart that you would have thought them more like dead men than living; the memory of their former vigour and glory was extinguished". Walsingham points out that they did not want to fight and suggests they may have been on the side of the peasants. (19)

John Ball sent a message to Richard II stating that the rising was not against his authority as the people only wished only to deliver him and his kingdom from traitors. Ball also asked the king to meet with him at Blackheath. Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales, the treasurer, both objects of the people's hatred, warned against meeting the "shoeless ruffians", whereas others, such as William de Montagu, the Earl of Salisbury, urged that the king played for time by pretending that he desired a negotiated agreement. (20)

Richard II agreed to meet the rebels outside the town walls at Mile End on 14th June, 1381. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End". (21)

John Ball at Mile End from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract". (22)

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". (23) However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London. (24)

While the king was in Mile End discussing an agreement with the king, another group of peasants marched to the Tower of London. There were about 600 soldiers defending the Tower but they decided not to fight the rebel army. Simon Sudbury (Archbishop of Canterbury), Robert Hales (King's Treasurer) and John Legge (Tax Commissioner), were taken from the Tower and executed. Their heads were then placed on poles and paraded through the streets of cheering Londoners. (25)

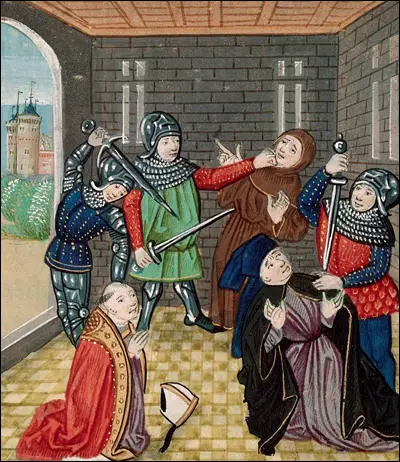

The killing of Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales

from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

Rodney Hilton argues that the rebels wanted revenge on all those involved in the levying of taxes or the administrating the legal system. Roger Leggett, one of the most important government lawyers was also killed. "They attacked not only the lawyers themselves - attorneys, pleaders, clerks of the courts - but others closely associated with the judicial processes... The hostility to lawyers and to legal records was not of course peculiar to the Londoners. The widespread destruction of manorial court records is well-known" during the rebellion. (26)

The rebels also attacked foreign workers living in London. "The commons made proclamation that every one who could lay hands on Flemings or any other strangers of other nations might cut off their heads". (27) It has been claimed that "some 150 or 160 unhappy foreigners were murdered in various places - thirty-five Flemings in one batch were dragged out of the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and beheaded on the same block... The Lombards also suffered, and their houses yielded much valuable plunder." (28)

Death of Wat Tyler

It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins. (29)

The death of Wat Tyler from Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1470)

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded." (30)

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages. (31)

Primary Sources

(1) Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's (1381)

And the king said to Wat Tyler: "Why will you not go back to your own county?" Wat Tyler answered that neither he nor his fellows would leave until they had got their charter as they wished to have it... And he demanded that there should be only one bishop in England... and all the lands and possessions (of the church) should be taken from them and divided among the commons... And he demanded that there should be no more villeins in England, and no serfdom... that all men should be free.

(2) Jean Froissart, Chronicles (c. 1395)

Then the king ordered thirty clerks to write letters, sealed with his seal. And when the people received the letters, they went back home. But Wat Tyler, Jack Straw and John Ball said they would not leave. More than 30,000 stayed with them. They were in no hurry to have the King's letters. They meant to slay all the rich people of London and rob their homes.

(3) Michael Senior, Richard II (1981)

It (Wat Tyler's character) is not a pleasant sight, and Richard undoubtedly benefits by comparison. But history is not written by peasants... One would expect Tyler to have had a bad press... but those reports, however partial, are all we have to go on.

(4) Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's (1381)

Wat Tyler, in the presence of the king, sent for a jug of water to rinse his mouth... as soon as the water was brought he rinsed out his mouth in a very rude and villainous manner before the king... At that time a certain valet from Kent... said aloud that Wat Tyler was the greatest thief and robber in all Kent... For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded.

(5) Thomas Walsingham, The History of England (c. 1420)

Sir John Newton came up to him on a war horse to hear what he (Wat Tyler) proposed to say. Tyler grew angry because the knight had approached him on horseback and not on foot, and furiously declared that it was more fitting to approach his presence on foot than by riding on a horse. Newton, still not completely forgetful of his old knightly honour, replied, "As you are sitting on a horse it is not insulting for me to approach you on a horse." At this the ruffian brought out his knife and threatened to strike the knight and called him a traitor...

On this the king, although a boy and of tender age, took courage and ordered the mayor of London to arrest Tyler. The mayor, a man of spirit and bravery, arrested Tyler and struck him a blow on the head which hurt him badly. Tyler was soon surrounded by the other servants of the king and pierced by sword thrusts in several parts of his body. His death... was the first incident to restore to the English knighthood their almost extinct hope that they could resist the commons.

(6) Hyman Fagan, Nine Days That Shook England (1938)

Walworth strikes, once, twice, and Tyler falls back on his horse, wounded in the neck and head. Now the whole royal mob runs amok.... He who had been so strong, so alive, so vital... he who had felt... the pain and agony of the branding, the hunger and poverty of his comrades and the tears of their families; he who had devoted his life to revolution so that all might live in peace and happiness. They were murderers, murdering in cold blood the man who had approached them in good faith.

(7) Henry Knighton, Chronicles (c. 1390)

Tyler stayed close to the king and spoke on behalf of the other rebels. He had drawn his knife, commonly called a dagger, and kept throwing it from hand to hand like a boy playing a game. It was believed that he would take the opportunity to stab the king suddenly if the latter refused what he demanded; those who stood near the king certainly feared what would happen. The rebels asked the king that all water, parks and woods should be made common to all: so that throughout the kingdom the poor as well as the rich should be free to take game in water, fish ponds, woods and forests... When the king paused to consider these demands, Wat Tyler approached the king and spoke threateningly to him. When John de Walworth, mayor of London, noticed this, he feared the king was about to be killed and knocked Wat Tyler into the gutter with his sword. Thereupon another squire called Ralph Standish pierced his side with another sword... When Tyler was dead, he was dragged by his hands and feet like a vile thing into the nearby church of St Bartholomew.

(8) John Trevisa, World History (c. 1390)

John the tiler, leader of the peasants... did not show due honour to his royal majesty. Rather he addressed the king's person with his head covered and with a threatening expression. The mayor... resenting the lack of reverence due to a king from his subject, addressed John in these words: "Why do you show no reverence to your king?" The rebel leader replied, "No honour will be shown by the king to me." To which the mayor responded, "Then I arrest you." The tiler drew his knife and tried to strike the mayor. The mayor then rushed to him and wounded him with a sword, while another squire who was present seized the head of the leader and threw him from his horse to the ground... When the whole mob shouted out, "Our chief is killed", the king replied, "Be still: I am your king, your leader and your chief."

Student Activities

Death of Wat Tyler (Answer Commentary)

Medieval Historians and John Ball (Answer Commentary)

The Peasants' Revolt (Answer Commentary)

Taxation in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

King John and the Magna Carta (Answer Commentary)

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

Richard the Lionheart (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)