Robert Morant

Robert Laurie Morant, the only son of Robert Morant and Helen Berry Morant, was born in Hampstead, London, on 7th April 1863. His father was a designer of high-class furniture and silk fabrics. He was educated at Winchester College and New College and graduated with a first class degree in theology from the University of Oxford in 1885. (1)

In 1886 he travelled to Siam (Thailand) where he became tutor to the crown prince. Morant involved himself in the reconstruction of the Siamese educational system. He also engaged in political activity and he was seen by some as acting as if he was "the Uncrowned King of Siam". During this period Florence Nightingale commented he had great genius, but some want of will or some want of harmony". (2)

On his return Morant took up both residence and a staff appointment at the Toynbee Hall settlement in the East End of London. Founded by Samuel Augustus Barnett and Henrietta Barnett in 1884, residents ave up their weekends and evenings to do relief work. This work ranged from visiting the poor and providing free legal aid to running clubs for boys and holding University Extension lectures and debates. The volunteers included Richard Tawney, Clement Attlee, Alfred Milner and William Beveridge.

As Seth Koven has pointed out: "Settlements, as first envisioned by the Barnetts, were residential colonies of university men in the slums intended to serve both as centres of education, recreation, and community life for the local poor and as outposts for social work, social scientific investigation, and cross-class friendships between élites and their poor neighbours." (3)

Beatrice Webb and her husband, Sidney Webb, met Morant at Toynbee Hall and she later recalled: "We have known and liked Morant since he appeared as a student in the early days of the London School of Economics - an abnormally tall and loosely knit figure, handsome in feature, shy in manner, and enigmatical in expression. At that time he was a little over thirty and at a loose end, having failed to keep an official position at the court of Siam." Beatrice then added that he was "a strange mortal, not altogether sane". (4)

In August 1895, Morant joined the civil service and Michael E. Sadler appointed him as assistant director of special inquiries and reports. Sadler claimed that the main objective was to "tell the truth, disclose the strong and weak points of great educational policies, and behave with self restraint but unshakeable honesty in presenting matter to the Department of Education and in its published volumes of reports". (5)

During a period of poor health Morant was nursed by Helen Mary Cracknell, daughter of Edwin Cracknell of Wetheringsett Grange, Suffolk; they married in 1896 and had a son and a daughter. Over the next few years he produced important research studies of the French and Swiss educational systems. His reports did not always please Sadler who later said that "Morant had no use for scientific impartiality". (6)

Robert Morant and the 1902 Education Act

Morant's work was appreciated by John Eldon Gorst, the Vice-President of the Committee on Education, who appointed him as his private secretary. Morant played an important role in advising Arthur Balfour, in drafting the 1902 Education Act. It was an attempt to overturn the 1870 Education Act that had been brought in by William Gladstone. It had been popular with radicals as they were elected by ratepayers in each district. This enabled nonconformists and socialists to obtain control over local schools.

The new legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools. At the time more than half the elementary pupils in England and Wales. For the first time, as a result of this legislation, church schools were to receive public funds. (7)

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against the proposed act. David Lloyd George led the campaign in the House of Commons as he resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. "The school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress." (8)

In July, 1902, a by-election at Leeds demonstrated what the education controversy was doing to party fortunes, when a Conservative Party majority of over 2,500 was turned into a Liberal majority of over 750. The following month a Baptist came near to capturing Sevenoaks from the Tories and in November, 1902, Orkney and Shetland fell to the Liberals. That month also saw a huge anti-Bill rally held in London, at Alexandra Palace. (9)

Despite the opposition the Education Act was passed in December, 1902. John Clifford, the leader of the Baptist World Alliance, wrote several pamphlets about the legislation that had a readership that ran into hundreds of thousands. Balfour accused him of being a victim of his own rhetoric: "Distortion and exaggeration are of its very essence. If he has to speak of our pending differences, acute no doubt, but not unprecedented, he must needs compare them to the great Civil War. If he has to describe a deputation of Nonconformist ministers presenting their case to the leader of the House of Commons, nothing less will serve him as a parallel than Luther's appearance before the Diet of Worms." (10)

Workers' Educational Association

In April 1903 Robert Morant become the permanent secretary of the Board of Education. His former boss and the man who expected the post, Michael E. Sadler, claimed: "Morant was a very able, unscrupulous arriviste with a lot of educational enthusiasm, great energy, and a tongue that could be honeyed or rasping... An Italian renaissance type I used to think then, but now I see in him an early arrival of the Fascist mentality". (11)

Morant reorganized the Board of Education into an effective central instrument for the implementation of the act, which was characterized by a balance of power between the centre and the local authorities. The board made its presence felt with a series of regulations issued in bold type in publications with differently coloured covers for each type of institution. This included Regulations for the Instruction and Training of Pupil-Teachers, Elementary School Code, Regulations for Secondary Education, Regulations for Training Colleges and Regulations for Evening Schools and Technical Institutes. (12)

Morant also took a keen interest in working-class education and was pleased when Albert Mansbridge established the Workers' Educational Association (WEA). By June 1906 the WEA had 47 branches. The autonomy of these branches was reflected in the wide variety of activities which they promoted. This included lectures and classes in the arts and social sciences, reading groups and nature-study rambles. (13)

The Conservative Party government, under the leadership of Arthur Balfour, gave its full support to this new organisation. Winston Churchill was especially pleased with this new development. He wrote that he was "in full... agreement with the objects of the association" and "it ought to be perfectly possible in this country for a man of high, if not necessarily and extraordinary, intellectual capacity to obtain with industry and perseverance the best education in the world, irrespective of his standing in life." (14)

A conference organized by the WEA was held in Oxford on 10th August 1907. It soon became clear that the delegates had different opinions about the direction of the WEA. Robert Morant argued that it would be possible to obtain financial support if the type of education provided was acceptable to the government: "In particular we believe that it is to small classes and solid earnest work that we can give increasingly of the golden stream." (15)

However, John Mactavish, a Portsmouth shipwright and a Labour Party activist, took a more militant view. He wanted a socialist rather than a liberal education. "I claim for my class all the best that Oxford has to give. I claim it as a right, wrongfully withheld". Mactavish believed that the WEA should train "missionaries... for the great task of lifting their class." For this purpose they needed new interpretations of history and economics. "You cannot expect the people to enthuse over a science which promises no more than a life of precarious toil." (16)

Philip Snowden agreed with Mactavish: "I would rather have better education given to the masses of the working classes than the best for a few. O God, make no more saints; elevate the race." (17) A WEA report published the following year made a similar point: "In obtaining a university education... it must not be necessary for working people to leave the class in which they were born... What they desire is not that men should escape from their class, but that they should remain in it and raise its whole level." (18)

National Insurance Act

During his speech on the People's Budget, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, pointed out that Germany had a compulsory national insurance against sickness since 1884. He argued that he intended to introduce a similar system in Britain. With a reference to the arms race between Britain and Germany he commented: "We should not emulate them only in armaments." (19)

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent one of his Treasury civil servants, William J. Braithwaite, to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued." (20)

One of the questions that arose during this meeting was whether British national insurance should work, like the German system, on the "dividing-out" principle, or should follow the example of private insurance in accumulating a large reserve. Lloyd George favoured the first method, but Braithwaite fully supported the alternative system. (21) He argued: "If a fund divides out, it is a state club, and not an insurance. It has no continuity - no scientific basis - it lives from day to day. It is all very well when it is young and sickness is low. But as its age increases sickness increases, and the young men can go elsewhere for a cheaper insurance." Lloyd George replied: "Why accumulate a fund? The State could not manage property or invest with wisdom. It would be very bad for politics if the State owned a huge fund." (22)

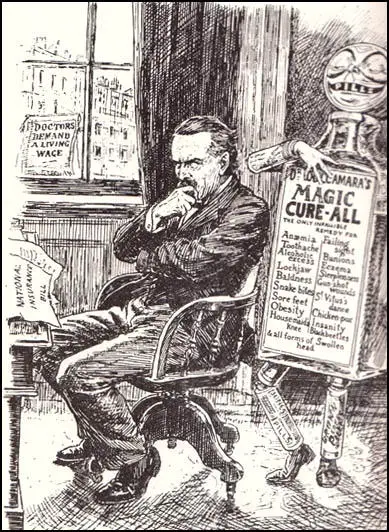

Patent Medicine: "Never mind, dear fellow, I'll stand by you - to the death!"

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911. (23)

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. David Lloyd George appointed Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. Morant took the job because he wanted the "opportunity it gave him of working towards the unification of the nation's health services". (24)

William J. Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation, but his relations with Morant were deeply strained. "Overworked and on the verge of a breakdown, he was persuaded to take a holiday, and on his return he was induced to take the post of special commissioner of income tax in 1913." (25)

Lloyd George has been criticised for not appointing Braithwaite as the chief executive of the health insurance system. John Grigg has argued that Lloyd George was fully justified in making this decision. "Since he (Braithwaite) was a fairly junior member of the official hierarchy, his appointment to such a responsible position would have been resented by many of his seniors and contemporaries at the Treasury, whose goodwill was needed by the Commission." (26)

Christopher Hollis believes that the main reason that Morant got the job was that he had the support of Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and other senior members of the Fabian Society: "Human nature being what it is, it was perhaps natural that Braithwaite should have felt grievance at first when he did not get the job on which he had set his heart, nor do we find it difficult to believe that the job was given to Morant for reasons of political convenience - to keep quiet the Webbs". (27)

As Beatrice Webb pointed out: "Morant is the one man of genius in the Civil Service, but he excites violent dislike in some men and much suspicion in many men. He is public spirited in his ends but devious in his methods… He certainly does not want social democracy - he is an aristocrat by instinct and conviction… but in spite of his malicious tongue and somewhat tortuous ways, he has done more to improve English administration than any other man." (28)

During the First World War he was a member of the Haldane Committee on the machinery of government. When the Ministry of Health was created in June 1919, from a merger of the Local Government Board and the Insurance Commission, Morant became its first permanent secretary. (29)

Robert Morant died after an attack of pneumonia on 13th March 1920.

Primary Sources

(1) Geoffrey K. Fry, Robert Morant: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

In November 1911 Morant resigned from the Board of Education and accepted an offer from the chancellor of the exchequer to become chairman of the National Insurance Commission for England. He had told Lloyd George that the only reason that he had taken on what the chancellor himself had described as the ‘gigantic task’ of implementing the National Insurance Act was the opportunity it gave him of working towards the unification of the nation's health services, which had been his ambition ever since Newman and he had issued their first circular on the medical inspection of schoolchildren. The most immediate task was to ensure that the administrative arrangements were in place to ensure that by the set date of 15 July 1912 there was machinery to collect the contributions of 12 million people and their employers. At first Lloyd George supported Treasury objections to more than minimal staffing of the commission, but Morant told him forcefully that the legislation would fail unless he was given a free hand to recruit the people he needed, and the chancellor gave way. Government departments were more eager to get rid of their troublemakers than their most gifted administrators; but, however random the selection, this trawl for talent was the first time that the first division of the civil service had been treated as other than a collection of departmental élites, and among the men who came to work with Morant were future stars of the higher civil service of the order of Warren Fisher, John Anderson, and Arthur Salter. The deadline for establishing the contributions machinery was met on time, but that still left another deadline, that which loomed on 15 January 1913, the date set for the introduction of the general practitioner service. The opposition of the medical profession was overcome, and this deadline was also met. Later in 1913 Morant made use of a provision in the act for the establishment of a fund for promoting medical research and the Medical Research Committee was established, which proved to be the forerunner of the Medical Research Council. Morant was the effective author of the National Insurance Act of 1913, which eliminated various flaws experienced in the working of the earlier legislation.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)