On this day on 9th April

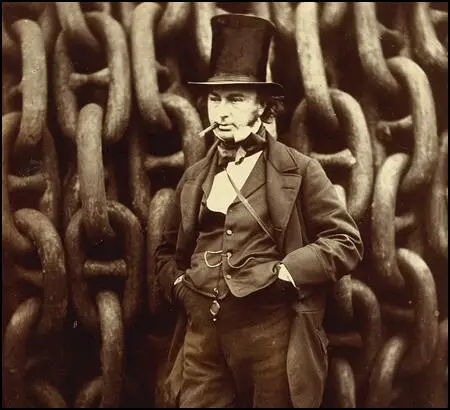

On this day in 1806 Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the only son of the French civil engineer, Sir Marc Brunel, was born in Portsmouth. He was educated at Hove, near Brighton and the Henri Quatre in Paris. In 1823 Brunel went to work with his father on the building of the Thames Tunnel. He was later to be appointed as resident engineer at the site.

In 1829 Brunel designed a suspension bridge to cross the River Avon at Clifton. His original design was rejected on the advice of Thomas Telford, but an improved version was accepted but the project had to be abandoned because of a lack of funds.

After being appointed chief engineer at the Bristol Docks in 1831, Brunel designed the Monkwearmouth Docks. He later went on to design and build similar docks at Plymouth, Cardiff, Brentford and Milford Haven.

In March 1833, the 27 year old Isambard Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway. His work on the line that linked London to Bristol, helped to establish Brunel as one of the world's leading engineers. Impressive achievements on the route included the viaducts at Hanwell and Chippenham, the Maidenhead Bridge, the Box Tunnel and the Bristol Temple Meads Station. Controversially, Brunel used the broad gauge (2.2 m) instead of the standard gauge (1.55m) on the line. This created problems as passengers had to transfer trains at places such as Gloucester where the two gauges met.

Brunel persuaded the Great Western Railway Company to let him build a steam boat to travel from Bristol to New York. The Great Western made its first voyage to New York in 1838. At that time the largest steamship in existence was 208 feet long, whereas the Great Western was 236 feet long. The journey to America took fifteen days and over the next eight years made 60 crossings.

The next steamship that Brunel built in Bristol was the Great Britain. It had an iron hull and was fitted with a propeller with six blades. The Great Britain was designed to carry 250 passengers, 130 crew and 1,200 tonnes of cargo. She made her first voyage from Liverpool to New York in 1845.

In 1852 Isambard Kingdom Brunel was employed by the Eastern Steam Navigation Company to build another steamship, the Great Eastern. Built on the Thames, the ship had an iron hull and two paddle wheels. The Great Eastern was extremely large and was designed to carry 4,000 passengers. Brunel was faced with a series of difficult engineering problems to overcome on this project and the strain of the work began to affect his health. While watching the Great Eastern in her trials, Brunel suffered a seizure. Isambard Kingdom Brunel died on 15th September, 1859 and was buried at Kensal Green cemetery five days later.

On this day in 1860 Emily Hobhouse, the daughter of the Reginald Hobhouse and Caroline Trelawny, was born in Liskeard, Cornwall on 9th April, 1860. Educated at home, Emily lived with her parents until she was thirty-five.

After the death of her father in 1895, Emily became more involved in social work and political reform. With her brother, Leonard Hobhouse, she was active member of the Adult Suffrage Society.

Emily, like many members of the radical wing of the Liberal Party, was opposed to the Boer War. Over the first few weeks of the war Emily spoke at several public meetings where she denounced the activities of the British government.

In late 1900 Emily was sent details of how women and children were being treated by the British Army. She later wrote: "poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance. And from that moment I was determined to go to South Africa in order to render assistance to them".

In October 1900, Emily formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children. An organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund.

Emily Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. After meeting Alfred Milner, she gained permission to visit the concentration camps that had been established by the British Army. However, Lord Kitchener objected to this decision and she was now told she could only go to Bloemfontein.

She left Cape Town on 22nd January, 1901, and arrived at Bloemfontein two days later. There were at the time eighteen hundred people in the camp. Emily discovered "that there was a scarcity of essential provision and that the accommodation was wholly inadequate." When she complained about the lack of soap she was told, "soap is an article of luxury". She nevertheless succeeded ultimately to have it listed as a necessity, together with straw and kettles in which to boil the drinking water.

Over the next few weeks Emily visited several camps to the south of Bloemfontein, including Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley and Orange River. She was also allowed to visit Mafeking. Everywhere she directed the attention of the authorities to the inadequate sanitary accommodation and inadequate rations.

By the time that Emily returned to Bloemfontein in March 1901, the population had grown considerably. She later wrote: " The population had redoubled and had swallowed up the results of improvements that had been effected. Disease was on the increase and the sight of the people made the impression of utter misery. Illness and death had left their marks on the faces of the inhabitants. Many that I had left hale and hearty, of good appearance and physically fit, had undergone such a change that I could hardly recognize them."

Hobhouse argued that Kitchener’s "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted.

Emily decided that she had to return to England in an effort to persuade the Marquess of Salisbury and his government to bring an end to the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. David Lloyd George and Charles Trevelyan took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps.

The vast majority of MPs showed little sympathy to the plight of the Boers. Hobhouse later wrote: "The picture of apathy and impatience displayed here, which refused to lend an ear to undeserved misery, contrasted sadly with the scenes of misery in South Africa, still fresh in my mind. No barbarity in South Africa was as severe as the bleak cruelty of an apathetic parliament."

In August, 1901, the British government established a commission headed by Millicent Fawcett to visit South Africa. While the Fawcett Commission was carrying out the investigation, the government published its own report. According to the New York Times: “The War Office has issued a four-hundred-page Blue Book of the official reports from medical and other officers on the conditions in the concentration camps in South Africa. The general drift of the report attributes the high mortality in these camps to the dirty habits of the Boers, their ignorance and prejudices, their recourse to quackery, and their suspicious avoidance of the British hospitals and doctors.”

The Fawcett Commission confirmed almost everything that Emily Hobhouse had reported. After the war a report concluded that 27,927 Boers had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all, about one in four of the Boer inmates, mostly children, died. However, the South African historian, Stephen Burridge Spies argues in Methods of Barbarism: Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics (1977) that this is an under-estimate of those who died in the camps.

Hobhouse decided to return to South Africa but was warned by the authorities they would refuse permission for her to visit the camps. When Hobhouse arrived in Cape Town on Sunday 27th October, 1901, she was not allowed to leave her ship. In poor health, she decided to recuperate in the mountains of Savoy. It was while she was there that Hobhouse heard that the Boer leaders had signed the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging.

Emily Hobhouse was also an opponent of British involvement in the First World War. On 3rd September, 1916, she wrote to a friend: "Think of our beloved fatherland, think of beautiful Italy, of France and of Germany, all of them working at full capacity to produce weapons of war and destruction. It seems as if we have reached the end of our civilization. It is all too hideous for words".

In 1921 the people of South Africa raised £2,300 and sent it to Hobhouse in recognition for the work she had done on their behalf during the Boer War. The money was sent to her with the explicit mandate that she had to buy a small house for herself somewhere along the coast of Cornwall. On 18th May, 1921, she replied: "I find it impossible to give expression to the feelings that overpowered me when I heard of the surprise you had prepared for me. My first impulse was not to accept any gift, or otherwise to devote it to some or other public end. But after having read and reread your letter, I have decided to accept your gift in the same simple and loving spirit in which it was sent to me."

Hobhouse purchased a house at St. Ives. On Christmas Day, 1921, she wrote to the organisers of the fund: "To you I owe everything that surrounds me now and that gives me a feeling of comfort and rest and security - the warmth of my little room - and the feeling of being at home. When I look back upon the year that has passed, I marvel more and more at everything that you and your people have done to ensure my happiness and my welfare".

Emily Hobhouse died in London on 8th June, 1926.

On this day in 1865 Erich Ludendorff, the third of six children, was born near Posen on 9th April 1865. His father, August Wilhelm Ludendorff (1833-1905), was a landowner. He was educated at the Cadet School at Plön. An intelligent student he was placed in a class two years ahead of his actual age group.

In 1885 Ludendorff was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 57th Infantry Regiment. He later served with the 2nd Marine Battalion and the 8th Grenadier Guards. In 1893 he attended the War Academy and the following year was appointed to the General Staff of the German Army. By 1911 he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

Ludendorff worked with General Alfred von Schlieffen on what became known as the Schlieffen Plan. Schlieffen argued that if war took place it was vital that France was speedily defeated. If this happened, Britain and Russia would be unwilling to carry on fighting. Schlieffen calculated that it would take Russia six weeks to organize its large army for an attack on Germany. Therefore, it was vitally important to force France to surrender before Russia was ready to use all its forces.

Schlieffen's plan involved using 90% of Germany's armed forces to attack France. Fearing the French forts on the border with Germany, Alfred von Schlieffen suggested a scythe-like attack through Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg. The rest of the German Army would be sent to defensive positions in the east to stop the expected Russian advance.

Ludendorff used his influence to persuade the Reichstag to increase military spending and to adopt a more agressive foreign policy. This upset the Social Democratic Party and in January 1913 Ludendorff was dismissed from the General Staff and was forced to return to regimental duties and was given the command of the 39th Fusiliers at Dusseldorf.

On the outbreak of the First World War was appointed Chief of Staff in East Prussia. Working with Paul von Hindenburg, commander of the German Eighth Army, Ludendorff won decisive victories over the Russians at Tannenberg (1914) and the Masaurian Lakes (1915).

Paul von Hindenburg replaced Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of Staff of the German Army in August, 1916. Hindenburg appointed Ludendorff as his quartermaster general. Soon afterwards, Ludendorff and Hindenburg became the leaders of the military-industrial dictatorship Third Supreme Command. Ludendorff supported unrestricted submarine warfare and successfully put pressure on Kaiser Wilhelm II to dismiss those in the armed forces that favoured a negotiated peace settlement.

Ludendorff gradually became the dominant figure in the Third Supreme Command and after the resignation of Theobald Bethmann Hollweg in July, 1917, took effective political, military and economic control of Germany. After the withdrawal of Russia from the war in 1917 Ludendorff was a key figure in the Brest-Litovsk negotiations.

With the Spring Offensive Ludendorff expected to breakthrough on the Western Front. When this ended in failure Ludendorff realised that Germany would lose the war. On 29th September 1918, the Third Supreme Command transferred power to Max von Baden and the Reichstag. By the end of October, Baden's government was strong enough to force Ludendorff's resignation.

After the signing of the Armistice, Ludendorff moved to Sweden where his wrote books and articles claiming that the unbeaten German Army had been "stabbed in the back" by left-wing politicians in Germany. He also published his memoirs, My War Memories, 1914-1918 (1920).

Fritz Thyssen later recalled: "I went to see Ludendorff chiefly to pay him a call of courtesy, but also in order to discuss with him the great national questions which then preoccupied his mind as much as mine. I deplored the fact that there were not at that time men in Germany whom an energetic national spirit would inspire to improve the situation... He recommended to me in particular the Overland League and, above all, the National Socialist party of Adolf Hitler." Ludendorff told Thyssen: "He (Hitler) is the only man who has any political sense. Go and listen."

Erich Ludendorff eventually returned to Germany where he participated in both the Kapp Putsch (March, 1920) and the Munich Putsch (November, 1923). The following year he became one of the first supporters of the Nazi Party in the Reichstag. Ludendorff was the right-wing Nationalist candidate in the 1925 Presidential Elections but won less than 1 per cent of the vote.

In 1931 Ella Winter visited Germany. She managed to obtain an interview with Ludendorff. He asked her what magazines she was working for. Winter replied, Harper's Magazine and Scribner's Magazine. Ludendorff commented: "In the hands of Freemasons, both of them; of course you know that... The Freemasons, the Bolsheviks, the world international financiers are trying to rule the world... They and the Jews." Winter later pointed out: "I had not heard such talk outside a mental hospital and did not know how to proceed with a supposedly rational political interview."

Erich Ludendorff died on 20th December 1937.

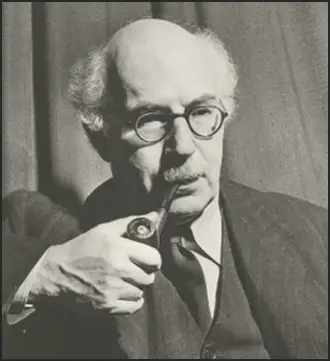

On this day in 1893 Victor Gollancz, the son of Alexander Gollancz, a prosperous wholesale jeweller, was born in London in 1893. After his education at St. Paul's School and New College, Oxford, he became a schoolmaster at Repton School.

In 1917 Seebohm Rowntree recruited Gollancz as a member of his Reconstruction Committee, an organisation he hoped would help plan the reconstruction of Britain after the war. Gollancz became a strong supporter of William Wedgwood Benn, the Liberal MP for Leith. Gollancz worked closely with Benn as secretary of the Radical Research Group. In 1921 Benn introduced Gollancz to his brother, Ernest Benn, the managing director of the publishers, Benn Brothers.

On the recommendation of William Wedgwood Benn, Gollancz was employed by Benn Brothers to develop the list of magazines the company published. Within six months Gollancz had convinced Ernest Benn to let him publish a series of art books. The books were a great success and during a seven year period turnover increased from £2,000 to £250,000 a year. Benn wrote in his diary that the increased company profits "reflects the greatest credit to the genius of Victor Gollancz".

Victor Gollancz also recruited novelists such as Edith Nesbit and H. G. Wells. He employed Gerald Gould, fiction editor of the Observer, as chief manuscript reader. Gollancz realised that if he published works selected by Gould, the books would be guaranteed at least one good newspaper review. Gollancz believed that good reviews was a major factor in the selling of books. In critics liked a book published by the company, Gollancz purchased full-page adverts in national newspapers such as The Times and the Daily Herald to tell the public about the good reviews.

Although Ernest Benn believed Gollancz was a "publishing genius" he was unwilling to give him full control over the company. There were also political differences between the two men. Whereas Benn had moved to the right during the 1920s, Gollancz had moved sharply to the left and was now a strong supporter of the Labour Party. Gollancz had disapproved of the publication of Ernest Benn's own book, Confessions of a Capitalist, where he extolled the merits of laissez-faire capitalism.

In 1927 Gollancz left Ernest Benn and formed his own publishing company. Victor Gollancz was an immediate success. Using methods developed at Benn Brothers, he recruited writers such as George Orwell, Ford Madox Ford, Fenner Brockway, H. Brailsford and G. D. H. Cole.

In January 1936, Gollancz had lunch with Stafford Cripps and John Strachey, where they discussed the possibility of establishing a United Front against fascism. It was during this meeting that Gollancz suggested the idea of creating a Left Book Club. It was also agreed that Harold Laski, the Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics, would make an excellent partner in this venture. The main aim was to spread socialist ideas and to resist the rise of fascism in Britain. Gollancz announced: "The aim of the Left Book Club is a simple one. It is to help in the terribly urgent struggle for world peace and against fascism, by giving, to all who are willing to take part in that struggle, such knowledge as will immensely increase their efficiency."

Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977) has argued: "The basic scheme of the Club was simple. For 2s 6d members received a Left Book of the Month, chosen by the Selection Committee - which consisted of Gollancz, John Strachey and Harold Laski. Left-wing books could be guaranteed a high circulation without risk to the publisher, while members received them at a greatly reduced rate." As Ruth Dudley Edwards, the author of Victor Gollancz: A Biography (1987), pointed out: "They were a formidable trio: Laski the academic theoretician; Strachey the gifted popularizer; and Victor the inspired publicist. All three had known a lifelong passion for politics and all had swung violently left in the early 1930s. Only Victor did not describe himself as completely Marxist, though he was objectively indistinguishable from the real article."

The first book, France To-day and the People's Front, by Maurice Thorez, the French Communist leader, was issued in May 1936. This was followed by other books that dealt with the struggle against fascism in Europe. This included books by Stafford Cripps (The Struggle for Peace, November 1936), Konni Zilliacus, The Road to War, April 1937), G.D.H. Cole, The People’s Front (July 1937), Robert A. Brady, The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism, September 1937), Richard Acland (Only One Battle, November 1937), H. N. Brailsford (Why Capitalism Means War, August 1938), Frederick Elwyn Jones (The Battle for Peace, August 1938) and Leonard Woolf (Barbarians at the Gate, November 1939).

The Left Book Club also published several books on the impact of the Great Depression. This included George Orwell (The Road to Wigan Pier, March 1937), G.D.H. Cole and Margaret Cole, The Condition of Britain (April 1937), Wal Hannington (The Problem of the Distressed Areas (November 1937) and Ellen Wilkinson (The Town that was Murdered, September 1939).

The Spanish Civil War was another subject that was well-covered by the Left Book Club. This included Harry Gannes and Theodore Repard (Spain in Revolt, December 1936), Geoffrey Cox (Defence of Madrid, March 1937), Hewlett Johnson (Report of a Religious Delegation to Spain, May 1937), Hubertus Friedrich Loewenstein, A Catholic in Republican Spain (November 1937), Arthur Koestler (Spanish Testament, December 1937) and Frank Jellinek (The Civil War in Spain, June 1938). However, Victor Gollancz rejected the idea of publishing Homage to Catalonia. In the book George Orwell attempted to expose the propaganda disseminated by newspapers in Britain. This included attacks on both the right-wing press and the Daily Worker, a paper controlled by the Communist Party of Great Britain. Although one of the best books ever written about war, it sold only 1,500 copies during the next twelve years.

Gollancz had hoped to recruit 10,000 members in the first year. In fact, he achieved over 45,000. By the end of the first year the Left Book Club had had 730 local discussion groups, and it estimated that these were attended by an average total of 12,000 people every fortnight. As Ben Pimlott pointed out: "In April 1937 Gollancz launched the Left Book Club Theatre Guild with a full-time organiser; nine months later 200 theatre groups had been established, and 45 had already performed plays. Sporting activities and recreations were also catered for."

The success of the Left Book Club encouraged socialists to believe there was a market for a left-wing weekly. Gollancz was approached by a group of Labour MPs that included Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan, George Strauss and Ellen Wilkinson and it was agreed to start publishing Tribune. Gollancz joined the editorial board and William Mellor was recruited as editor. George Orwell, now recognised as Britain's leading left-wing writer, agreed to contribute articles and later became the literary editor of the paper.

Other important books published by the Left Book Club included Philip Noel-Baker (The Private Manufacture of Armaments, October 1936), Stephen Spender (Forward from Liberalism, January 1937), Clement Attlee (The Labour Party in Perspective, August 1937), John Lawrence Hammond and Barbara Hammond (The Town Labourer, August 1937), Edgar Snow (Red Star over China, October 1937), Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb (Soviet Communism: a New Civilisation, October 1937), Richard H. Tawney (The Acquisitive Society, November 1937), Eleanor Rathbone (War can be Averted, January 1938), Konni Zilliacus (Why the League has Failed, May 1938), Agnes Smedley (China Fights Back, December 1938), Joachim Joesten (Denmark’s Day of Doom, January 1939) and Victor Gollancz (Is Mr. Chamberlain Saving the Peace?, April 1939). By 1939 membership of the Left Book Club rose to 50,000.

Harry Pollitt remained loyal to Joseph Stalin until September 1939 when he welcomed the British declaration of war on Nazi Germany. He published a pamphlet entitled How to Win the War. It included the following passage: "The Communist Party supports the war, believing it to be a just war. To stand aside from this conflict, to contribute only revolutionary-sounding phrases while the fascist beasts ride roughshod over Europe, would be a betrayal of everything our forebears have fought to achieve in the course of long years of struggle against capitalism."

Joseph Stalinsigned the Soviet-Nazi Pact with Adolf Hitler in August, 1939. At a meeting of the Central Committee on 2nd October 1939, Rajani Palme Dutt demanded "acceptance of the (new Soviet line) by the members of the Central Committee on the basis of conviction". Despite the objections of several members, when the vote was taken, only Harry Pollitt, John R. Campbell and William Gallacher voted against. Pollitt was forced to resign as General Secretary and he was replaced by Dutt. William Rust took over Campbell's job as editor of the Daily Worker. Over the next few weeks the newspaper demanded that Neville Chamberlain respond to Hitler's peace overtures.

Victor Gollancz was appalled by this decision and in March 1941 the Left Book Club published Betrayal of the Left: an Examination & Refutation of Communist Policy from October 1939 to January 1941. The book was edited by Gollancz and included two essays by George Orwell, Fascism and Democracy and Patriots and Revolutionaries.

During the late 1930s and early 1940s Victor Gollancz was heavily involved in trying to get Jewish refugees out of Germany. After the war Gollancz worked hard to relieve starvation in Germany. He founded the Jewish Society for Human Service and its first objective was to help Arab relief.

Some members of the Left Book Club disapproved of the electoral truce between the main political parties during the Second World War. On 26th July 1941 members of the 1941 Committee led by Richard Acland, Vernon Bartlett and J. B. Priestley established the socialist Common Wealth Party. The party advocated the three principles of Common Ownership, Vital Democracy and Morality in Politics. The party favoured public ownership of land and Acland gave away his Devon family estate of 19,000 acres (8,097 hectares) to the National Trust.

In 1942 the Common Wealth Party decided to contest by-elections against Conservative candidates. The CWP needed the support of traditional Labour supporters. Tom Wintringham wrote in September 1942: "The Labour Party, the Trade Unions and the Co-operatives represent the worker's movement, which historically has been, and is now, in all countries the basic force for human freedom... and we count on our allies within the Labour Party who want a more inspiring leadership to support us." Large numbers of working people did support the SWP and this led to victories for Richard Acland in Barnstaple and Vernon Bartlett in Bridgwater. Later, Victor Gollancz argued that "had there been no Left Book Club there would have been no Bridgwater."

The Left Book Club continued to publish books throughout the Second World War and they no doubt helped to bring about the landslide victory of the Labour Party in the 1945 General Election. As his biographer, Ruth Dudley Edwards, pointed out: "By March 1947 he (Gollancz) was sick rather than just tired of the Left Book Club. With fascism defeated and a Labour government in power, the aims for which it had been set up were now irrelevant." With the Left Book Club down to 7,000 members, Victor Gollancz closed the organization down in October 1948.

After the Second World War political differences with George Orwell resulted in Gollancz not publishing two great novels, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. However, he had several important successes including Kingley Amis's Lucky Jim, John Updike's Rabbit, Run and Colin Wilson's The Outsider.

In the 1950s played an active role in the formation of the National Campaign for the Abolition of Capital Punishment (NCACP). In 1958 Gollancz joined with Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, J. B. Priestley, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Victor Gollancz died in 1967.

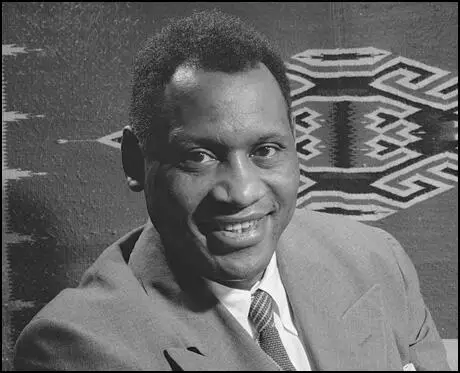

On this day in 1898 Paul Robeson, the son of William Drew Robeson, a former slave, was born in Princeton, New Jersey. Paul's mother, Maria Louisa Bustin, came from a family that had been involved in the campaign for African-American Civil Rights.

William Drew Robeson was pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church for over twenty years. He lost his post in 1901 after complaints were made about his "speeches against social injustice". Three years later Paul's mother died when a coal from the stove fell on her long-skirted dress and was fatally burned.

Paul's father did not find another post until 1910 when he became pastor of the St. Thomas A.M.E. Zion Church in the town of Somerville, New Jersey. Paul was a good student but was expected to do part-time work to help the family finances. At twelve Paul worked as a kitchen boy and later was employed in local brickyards and shipyards.

In 1915 Paul Robeson won a four-year scholarship to Rutgers University. Blessed with a great voice, Robeson was a member of the university's debating team and won the oratorical prize four years in succession. He also earned extra money my singing in local clubs.

Paul Robeson, was a large man (six feet tall and 190 pounds) and excelled in virtually every sport he played (baseball, basketball, athletics, tennis). In 1917 Robeson became the first student from Rutgers University to be chosen as a member of the All-American football team. However, in some games Robeson was dropped because the opponents refused to play against teams that included black players.

In 1920 Robeson joined the Amateur Players, a group of Afro-American students who wanted to produce plays on racial issues. Robeson was given the lead in Simon the Cyrenian, the story of the black man who was Jesus's cross-bearer. He was a great success in the part and as a result was offered the leading role in the play Taboo. The critics disliked the play but Robeson got good reviews for his performance.

In 1921 Paul Robeson married Eslanda Goode, a histological chemist at the Presbyterian Hospital in New York. They were soon parted when Robeson went to England to appear in the London production of Taboo, whereas Goode took up her post as the first African American analytical chemist at Columbia Medical Centre.

When Paul Robeson arrived back in the United States he returned to his studies and completed his law degree in February 1923. Soon afterwards he joined the Stotesbury and Milner law office in New York. The only African American in the company, Robeson was the victim of abuse from other members of staff. On one occasion, a stenographer refused to work with him saying "I never take dictation from a nigger". Robeson, who had recently joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), had a meeting with Louis William Stotesbury about this incident. Stotesbury sympathized with Robeson but told him that his prospects for a career in law were limited, as the company's wealthy white clients would be unlikely ever to agree to let him try a case before a judge, as they would fear it would hurt their case.

Paul Robeson decided to leave the legal profession and return to the theatre. He joined the Provincetown Theatre Group and after meeting Eugene O'Neill agreed to play in his play All God's Chillun Got Wings. News of the proposed production reached the press and the American Magazine, a journal owned by William Randolph Hearst, called for the play not to be shown. It especially objected to a scene where a white actress kissed Robeson's hand. Another scene that showed black and white children playing together also caused controversy.

The production went ahead and Robeson received tremendous reviews for his performance. George J. Nathan in the American Mercury wrote that Robeson "with relatively little experience and with no training to speak of, is one of the most thoroughly eloquent, impressive, and convincing actors that I have looked at and listened to in almost twenty years of professional theatre." The play eventually closed in October 1924 after a hundred performances.

Paul Robeson became increasingly concerned with the issue of civil rights. Two of his closest friends were Walter F. White and James Weldon Johnson, two leading figures in the NAACP. Interviewed by the New York Herald Tribune Robeson claimed that "if I do become a first-rate actor, it will do more toward giving people a slant on the so-called Negro problem than any amount of propaganda and argument.

In 1925 Robeson went to London to appear in Emperor Jones. In England he became close friends with Emma Goldman, an anarchist who had been deported from the United States after the First World War. In a letter Goldman wrote to Alexander Berkman, she said: "The more I know the man the greater and finer I find him". In another letter to Berkman she wrote about his "fine character, his understanding and his large outlook on life." She added: "I know few of our American friends among whites quite as humane and large as Paul." While in London he also met other radicals including Max Eastman, Claude McKay and Gertrude Stein.

On his return to the United States Robeson appeared in Black Boy and in January 1927 began a singing tour of Kansas and Ohio. This was followed by a concert tour of Europe and on his return took the role of Crown in the play Porgy, on Broadway in March 1928. This was followed by Show Boat in London where he performed Ole Man River. One critic, James Agate, of the Sunday Times, suggested that the producers cut a half-hour of the show and fill it with Robeson singing spirituals.

Following his success in Show Boat Robeson went on a concert tour of Europe. This included performances in Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. On his return to London he began a campaign against racial discrimination after he was refused service at the Savoy Grill. The issue was raised with Ramsay MacDonald, the British prime minister, who although condemned the behaviour of the restaurant he claimed "I cannot think of any way in which the Government can intervene." It was later discovered that the Savoy Grill had refused to serve Robeson after complaints had been made about his presence by white American tourists staying in London.

In 1930 Paul Robeson appeared in Emperor Jones in Germany before taking the leading role in Othello in London. The play received a great deal of publicity as it included a scene where Robeson kisses a white actress, Peggy Ashcroft, who played the role of Desdemona. Despite the controversy he show was a great success and ran for 295 performances.

Paul Robeson also appeared in several films including The Emperor Jones (1933) and Sanders of the River (1935). Robeson was upset with the producers of Sanders of the River as he claimed that they had turned it into a pro-imperialist film. He later wrote that "it is the only one of my films that can be shown in Italy and Germany, for it shows the Negro as Fascist States desire him - savage and childish."

In 1935 Robeson and his wife Eslanda Goode, visited the Soviet Union. While there he met William Patterson, one of the leaders of the American Communist Party who was staying in Moscow at the time. They also met two of Eslanda's brothers, John and Frank Goode, who had decided they wanted to live in a socialist country.

Paul Robeson and his wife were impressed with life in the Soviet Union. They liked the improved status of women and the quality of care in the hospitals. Most of all they approved of the way that the minorities were treated in the country. He later wrote that in the Soviet Union he had felt "like a human being for the first time since I grew up. Here I am not a Negro but a human being. Before I came I could hardly believe that such a thing could be. Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity."

On his return to the United States Robeson went to Hollywood to make a movie of Show Boat (1936). He followed this with the films: Jericho (1937), Song of Freedom (1937), Big Fella (1937) and King Solomon's Mines (1937).

Robeson was a strong supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain. On 24th June, 1937, Robeson spoke at a mass rally at the Albert Hall in London in aid of those fighting against General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist Army. In December 1937 he joined Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison, Ellen Wilkinson and other Labour Party leaders in speaking at another rally at the Albert Hall to attack the British government's Non-Intervention Agreement.

In January 1938 Robeson, Eslanda Goode and Charlotte Haldane visited the International Brigades fighting in Spain. While there he heard about Oliver Law of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion who had been killed at Brunete in July 1937. During the offensive Law became the first African-American officer in history to lead an integrated military force. Robeson decided to make a film about Law and "all of the American Negro comrades who have come to fight and die for Spain." Over the next few years Robeson tried several times to raise the money to make the film. He later complained that "the same money interests that block every effort to help Spain, control the Motion Picture industry, and so refuse to allow such a story."

On his return to London he joined the left-wing Unity Theatre and appeared in Ben Bengal's play, Plant in the Sun, a story about white and black workers who combine forces during a strike. He also appeared in a play about Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the Haitian revolution, with C. L. R. James at the Westminster Theatre.

Paul Robeson continued to be active in various political campaigns including the Spanish Aid Committee, Food for Republican Spain Campaign, National Unemployed Workers' Movement and the League for the Boycott of Aggressor Nations. On 27th June 1938, Robeson joined Stafford Cripps, Harold Laski and Ellen Wilkinson, at a rally at Kingsway Hall in favour of Indian Independence Movement.

A strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and his fascist government in Nazi Germany, Robeson was active in the League for the Boycott of Aggressor Nations. He joined the attacks on Neville Chamberlain and his Appeasement Policy but defended Joseph Stalin in his decision to sign the Nazi-Soviet Pact. This resulted in Robeson being attacked by other figures on the left such as Claude McKay who saw Stalin as an unprincipled dictator.

In 1941 Paul Robeson joined Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Vito Marcantonio in the campaign to free Earl Browder, the leader of the American Communist Party, who had been sentenced to four years imprisonment for violating passport regulations.

At the beginning of the Second World War Robeson argued for the United States not to become involved in the conflict. His views changed after the German Army invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. He now favoured United States intervention and a creation of a second front in Europe.

Paul Robeson also became an active member of Russian War Relief and along with Fiorello LaGuardia, Harry Hopkins and William Green at a rally on the subject at Madison Square Garden on 22nd July 1942. Robeson argued that the war offered the opportunity to bring an end to oppression and racial prejudice all over the world. At one rally in October 1943 he stated that "this is not a war for the liberation of Europeans and European nations, but a war for the liberation of all peoples, all races, all colours oppressed anywhere in the world."

Robeson continued to make films during the war. This included The Proud Valley (1940), in which he played a heroic miner in Wales and Tales of Manhattan (1942). Robeson was also involved in Native Land (1942), a film directed by Paul Strand. Robeson provided the narration and Marc Blitzstein the music.

In 1946 Robeson led a delegation of the American Crusade to End Lynching to see Harry S. Truman to demand that he sponsor anti-lynching legislation. He also became involved in the campaign to persuade African Americans to refuse the draft.

Robeson's political activities led to him being investigated by House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). On one occasion, when Richard Nixon, a member of the HUAC, asked the actor Adolphe Menjou, how the government could identify Communists, he replied, anyone who attended Robeson's concerts or who purchased his records.

The government decided that Robeson and his wife, Eslanda Goode, were members of the American Communist Party. Under the terms of the Internal Security Act, members of the party could not use their passports. Blacklisted at home and unable to travel abroad, Robeson's income dropped from $104,000 in 1947 to $2,000 in 1950.

Paul Robeson finally agreed to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955. He denied being a member of the American Communist Party but praised its policy of being in favour of racial equality. One Congressman, Gordon Scherer of Ohio, commented that if he had felt so free in the Soviet Union why he had not stayed there. Robeson replied: "Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part just like you."

In 1958 the government lifted the ban it had imposed prohibiting Paul Robeson from leaving the United States. After obtaining his passport, Robeson moved to Europe where he lived for five years. He spent his time writing, travelling and giving public lectures. Paul Robeson, whose autobiography, Here I Stand, was published in 1958, died in Philadelphia on 23rd January, 1976.

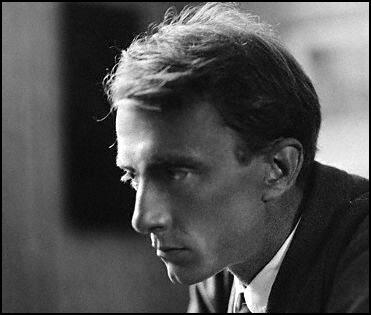

On this day in 1906 Hugh Gaitskell was born. Hugh Gaitskell, the youngest of the three children of Arthur Gaitskell (1870–1915), and his wife, Adelaide Gaitskell, was born on 9th April 1906. His father worked for the Indian Civil Service, and his mother was the daughter of George Jamieson, who had been consul-general in Shanghai.

Gaitskell was educated at Dragon School (1912–19), Winchester School (1919–24), and New College (1924–7). While at the University of Oxford he came under the influence of G. D. H. Cole. Gaitskell became a socialist during the 1926 General Strike and joined the Labour Party.

After graduating with a first in philosophy, politics, and economics in 1927, he spent a year as a Workers' Educational Association tutor in the Nottinghamshire coalfield. The WEA published a booklet on Chartism that he had written at university. According to his biographer, Brian Brivati: " It was a formative experience for him, both personally and politically. Personally, he lived briefly with a local woman and enjoyed his first mature relationship. Politically, he developed a less romantic view of the working class and learned much more about the practical aspects of socialism."

In 1928 he was appointed to a lectureship in political economy at University College. Gaitskell remained active in politics and in 1931 he joined with G. D. H. Cole in forming the New Fabian Research Bureau. The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies. It also attempted to promote the economic ideas of John Maynard Keynes within the Labour Party. One of their converts was Hugh Dalton.

Gaitskell was adopted as prospective Labour Party candidate for Chatham in autumn 1932, but was defeated by John Beresford, the Conservative Party candidate, when he stood there in the 1935 General Election.

On 9th April 1937 Gaitskell married Dora Frost, the daughter of Leon Creditor and the divorced wife of David Frost, a lecturer in physiology. They established a home at 18 Frognal Gardens, Hampstead, London. Her biographer, William Rodgers, has argued: "Dora Gaitskell settled easily into domestic life. Her first child by this marriage, a daughter, Julia, was born in 1939, and a second, Cressida, in 1942. She proved an affectionate and caring mother, creating a family life of a fairly traditional kind. She was confident in her husband's love and ultimate loyalty and, in turn, became a devoted wife, a tigress in defending him from his political enemies, and committed and affectionate towards his friends."

In 1938 was promoted to the post of head of department and the following year he published Money and Everyday Life (1939). Gaitskell was a strong opponent of appeasement and on the outbreak of the Second World War he was recruited into Whitehall, working for Hugh Dalton as a temporary civil servant in the Ministry of Economic Warfare from May 1940, and from February 1942 at the Board of Trade. At the 1945 General Election he was elected to represent South Leeds.

Clement Attlee considered Gaitskell as one of the most talented new members of the House of Commons and he was appointed parliamentary secretary to Emanuel Shinwell at the Ministry of Fuel and Power in May 1946. Gaitskell's main task was to help the passage of the Coal Nationalization Bill through Parliament. Brian Brivati has argued: "Gaitskell's first major task as a politician was to create and then deal with the shortcomings of nationalized industries. He believed in nationalization on grounds of efficiency, economies of scale, and rationalization of production, and considered it to be morally right. He also recognized its limitations. Although in public he defended the structure of the nationalized industries to the hilt, he was privately somewhat ambiguous about how the public corporation had been devised. The problem was that Gaitskell, like the rest of the Labour government, put far too much faith in the nationalization programme. The result could hardly be presented as the socialization of industry or indeed as having anything very much to do with socialism. Management structures and the exercise of authority in the workplace were largely unaltered. At best the change of ownership produced an enhancement of the unions' status. Gaitskell's hope for the industries was that the relationship between workers and employers would be transformed. That aspiration was never realized."

In October 1947 Gaitskell replaced Emanuel Shinwell as minister of fuel and power. This was a difficult time to hold the post and was heavily criticised for removing the basic petrol ration for private motorists. However, his supporters have argued that during this period he did some important work encouraging the building of oil refineries and the development of a petrochemical industry in Britain. Henry (Chips) Channon was a Conservative Party member who was impressed by Gaitskell: "Gaitskell has a Wykehamistical voice and manner and a 13th century face. He began in a moderate fashion, and at once put the House in a receptive mood by his clear enunciation and courteous manner; he was lucid, clear and coherent and there was a commendable absence of Daltonian sneers or bleak Crippsian platitudes. A breath of fresh air."

Clement Attlee promoted Gaitskell to minister for economic affairs in February 1950. When Richard Stafford Cripps resigned nine months later, Gaitskell was appointed to succeed him as chancellor of the exchequer. Herbert Morrison approved of the appointment: "I regarded him at that time as a man of considerable ability and with a praiseworthy desire to act in a sane and responsible manner." Aneurin Bevan disagreed and sent a letter commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement."

One of his first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973): "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon." The following day, three members of the government, Harold Wilson, Aneurin Bevan and John Freeman resigned.

Harold Wilson argued that Gaitskell took this action as part of a battle he was having with Aneurin Bevan: "He was certainly ambitious, and had close links with the right-wing trade unions. It was not long before that ambition took the form of a determination to outmanoeuvre, indeed humiliate, Aneurin Bevan. Hugh, for his part, despised what he regarded as emotional oratory, and if he could defeat Nye in open conflict, he would be in a strong position to oust Morrison as the heir apparent to Clement Attlee. At the same time he would ensure that post-war socialism would take a less dogmatic form, totally anti-communist but unemotional."

Some political experts believed that Gaitskell's budget was a major factor in the defeat of the government in the 1951 General Election. His biographer, Brian Brivati, disagrees: "No other political crisis in Gaitskell's career better illustrated how far his greatest strength - political courage and confidence - could turn into his singular weakness, stubbornness. His budget of 1951 did not lose the Labour government the election, but it did little or nothing to help the government win. There have been election-winning budgets, but Gaitskell was not in the business of delivering a reflation package. When he presented the outline of his proposals to Attlee, the prime minister's response was that there were not going to be very many votes in it. Gaitskell replied that he could not expect votes in a rearmament year. However, with the benefit of hindsight it is too easy to see the Labour administration as one that was running out of steam: a successful budget, a unified party, and careful timing could have produced a different result in 1951."

After the election defeat Gaitskell began the long campaign to replace Clement Attlee as leader of the Labour Party. His main rival was Herbert Morrison, also on the right of the party. However, to some members of the party, Morrison had run out of energy and they were attracted to the younger Gaitskell. As a former chancellor he was able to successfully lead the attack on the Conservative government's economic policies.

Denis Healey was another Shadow Cabinet member who disliked Gaitskell style of leadership. In his autobiography, The Time of My Life (1989), he pointed out: "I was worried by a streak of intolerance in Gaitskell's nature; he tended to believe that no one could disagree with him unless they were either knaves or fools. Rejecting Dean Rusk's advice, he would insist on arguing to a conclusion rather than to a decision. Thus he would keep meetings of the Shadow Cabinet going, long after he had obtained its consent to his proposals, because he wanted to be certain that everyone understood precisely why he was right. In the political world a leader must often be content with acquiescence; he is sometimes wise to leave education to his juniors."

George Brown was a supporter of Gaitskell in the shadow cabinet: "Hugh Gaitskell became too much the product of other people and the manoeuvring of other powerful figures and too little himself. Yet his capacity to inspire other people with his ideals was extraordinary. Had he lived he would have been a tremendous leader of young people and an enormous bulwark against the machine politicians, the bureaucrats and everything else which has tended to debase the currency of modern life."

In October, 1957 Aneurin Bevan decided to make a speech against unilateral nuclear disarmament at the party conference. His wife, Jennie Lee, disagreed strongly with his decision: "I did not argue with him that evening, he had to be left in peace to work things out for himself, but he was in no doubt that I would have preferred him to take the easy way. I dreaded the violence of the Conference atmosphere which I knew would be generated by the dedicated advocates of immediate unilateral nuclear disarmament, but, like Nye, I did not foresee the bitterness of the personal attacks made by some delegates who ought to have known him well enough not to have doubted his motives. Disagreement was one thing: character assassination another. Were these his friends? Were these his comrades he had fought for over so many years? Could they really believe that he was a small-time career politician prepared to sacrifice his principles in order to become second-in-command to the right-wing leader of the Party?

Bevan later recalled: "I knew this morning that I was going to make a speech that would offend and even hurt many of my friends. I know that you are deeply convinced that the action you suggest is the most effective way of influencing international affairs. I am deeply convinced that you are wrong. It is therefore not a question of who is in favour of the hydrogen bomb, but a question of what is the most effective way of getting the damn thing destroyed. It is the most difficult of all problems facing mankind. But if you carry this resolution and follow out all its implications and do not run away from it you will send a Foreign Secretary, whoever he may be, naked into the conference chamber."

Gaitskell urged Britain's entry to the European Economic Community but was unable to persuade the majority of members of the Labour Party to agree to this policy. After losing the 1959 General Election Gaitskell attempted to change party policy on nationalization (Clause IV). At the party conference in November 1959 he argued: "Why was nationalization apparently a vote loser? For two reasons, I believe. First, some of the existing nationalized industries, rightly or wrongly, are unpopular. This unpopularity is overwhelmingly due to circumstances which have nothing to do with nationalization. London buses are overcrowded and slow, not because the Transport Commission is inefficient, but because of the state of London traffic which the Tory Government has neglected all these years. The backward conditions of the railways are not due to bad management but to inadequate investment in the past, which has left British Railways with a gigantic problem of modernization.... Above all, we must face the fact that nationalization will not be positively popular until all these industries are clearly seen to be performing at least as well as the best firms in the private sector. When we have achieved that goal, then we can face the country with complete confidence."

Gaitskell continued her relationship with Ann Fleming. Senior figures in the Labour Party became concerned about his involvement with someone who was known to be a right-wing supporter of the Conservative Party. Gaitskell's biographer, Philip M. Williams, the author of Hugh Gaitskell (1979) has argued: "At home at Frognal Gardens his guests were mostly progressive and few were actively Tory. But he kept up a few personal friendships across the political divide, largely through Anne Fleming and her circle. Crosland chided him about it; but, with his Wykehamist sense of rectitude and distaste for the idle rich, Gaitskell was not in the least worried that he might yield to the embrace of the social Establishment, or might be sourly suspected of doing so. He appreciated its comforts, and its intellectual stimulus still more."

Andrew Lycett saw the relationship very differently: "He (Hugh Gaitskell) saw her (Ann Fleming) as a spirited and amusing antidote to his dour professional life; she liked his brains and political clout, and considered it a challenge to wean him from his puritanical socialist principles to an enjoyment of the more overt pleasures in life. On one level, she promoted Gaitskell with Beaverbrook and ensured that his policies received favourable Express group newspaper coverage in any internal Labour Party dispute with his left wing. On another, she subverted the Labour leader's pretensions to seriousness. Ann Fleming, the political hostess who split the Labour Party and kept the Labour right wing in business: it is an interesting and not implausible thesis."

In March 1960 Gaitskell persuaded the party's national executive to endorse a new statement of aims that played down the commitment to Clause IV. However, throughout that summer, the verdicts of union conferences showed that this new proposal would probably be rejected by that party's autumn conference. To avoid defeat Gaitskell withdrew the proposal.

Hugh Gaitskell felt very strongly about the party policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. At the party conference in Scarborough in October 1960, two unilateralist resolutions, from the transport workers and the engineers, were carried and the official policy document on defence was rejected. Gaitskell's thought these were disastrous decisions and made a passionate speech where he stressed that he would "fight and fight and fight again to save the party we love".

Harold Wilson now challenged Gaitskell for the leadership but was defeated by 166 votes to 81. Gaitskell now had the confidence to advance a defence policy that effectively rejected the Scarborough decisions. As Brian Brivati points out: "He and his allies sought to reverse the unilateralist commitments of the trade unions. They were sufficiently successful, though sometimes by only narrow margins, to secure a decisive vote in favour of multilateralism at the Labour Party conference held at Blackpool in October 1961. In the aftermath of Scarborough pro-Gaitskellite activists in the constituency parties and in the unions had come together in the Campaign for Democratic Socialism, a strongly revisionist group. Its impact on the complex shifts in trade union positions was small, but its long-term significance was in influencing the selection of parliamentary candidates."

In July 1961 Harold Macmillan applied for entry to the European Economic Community. Gaitskell had always been in favour of joining the EEC but he now changed his position. At the party conference in Brighton in October 1962 he argued that the prospects for a federal Europe as amounting to: "The end of Britain as an independent European state. I make no apology for repeating it. It means the end of a thousand years of history". Gaitskell's Brighton speech dismayed many of his closest friends. Dora Gaitskell commented: "All the wrong people are cheering".

Hugh Gaitskell was taken ill in December, 1962, and was taken to Middlesex Hospital, London. It was not until several weeks later that the doctors became aware he was suffering from the rare disease systemic lupus erythematosus. It can lie dormant for years, emerging from time to time in a different organ, or suddenly erupting everywhere as it did with Gaitskell. Both his heart and lungs were initially affected but then the disease attacked every critical organ at once and died on 18th January 1963.

Some members of MI5 believed that Harold Wilson was a Soviet agent. Anatoli Golitsyn, a KGB officer who defected in 1961, worked for the Department of Wet Affairs. This department was responsible for organizing assassinations. He said that just before he left he knew that the KGB were planning a high-level political assassination in Europe in order to get their man into the top place." Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009), has pointed out that senior figures in MI5 were not convinced by these claims.

Peter Wright, the principal scientific officer, who worked closely with Arthur Martin, who was responsible for Soviet Counter Espionage, found Golitsyn's testimony convincing and became convinced that Gaitskell was the victim of a KGB assassination. "I knew him (Gaitskell) personally and admired him greatly. I had met him and his family at the Blackwater Sailing Club, and I recall about a month before he died he told me that he was going to Russia. After he died his doctor got in touch with MI5 and asked to see somebody from the Service. Arthur Martin, as the head of Russian Counterespionage, went to see him. The doctor explained that he was disturbed by the manner of Gaitskell's death. He said that Gaitskell had died of a disease called lupus disseminata, which attacks the body's organs. He said that it was rare in temperate climates and that there was no evidence that Gaitskell had been anywhere recently where he could have contracted the disease."

Gaitskell told his doctors that he had visited the Soviet embassy just before his illness in search of a visa for his projected trip to Moscow. Though he had gone by appointment, he had been kept waiting half an hour and had been given coffee and biscuits. James Jesus Angleton the head of the CIA's Counter-Intelligence Staff, became convinced that Golitsyn was telling the truth and he ordered his staff to search the published medical literature of the fatal disease and discovered that Soviet medical researchers had published three academic papers describing how they had produced a drug that, when administered, reproduced the fatal heart and kidney symptoms suffered by Gaitskell. Chapman Pincher has argued that "the Labour leader's death was the single most important historic factor in the party's continuing swing to the left."

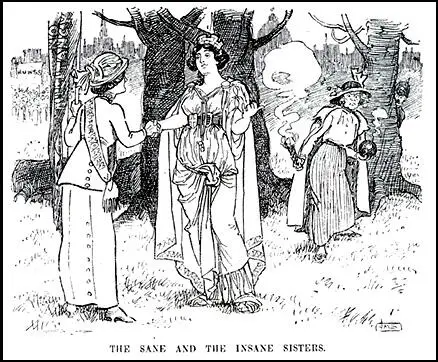

On this day in 1913 two bombs were left on the Waterloo to Kingston line, placed on trains going in opposite directions. One bomb was found at Battersea on the train coming from Kingston in a previously crowded third-class carriage. A railway porter had seen smoke slowly creeping from under a seat. He discovered a white wooden box containing a tin canister in which sixteen live gun cartridges, wired together and joined up with a small double battery, had been attached to a tube of explosive. Packed in among the cartridges were lumps of jagged metal, bullets and scraps of lead. Four hours later, as a train from Waterloo pulled into Kingston, the third-class carriage exploded and was quickly consumed by fire. Luckily the carriage was empty and no one was injured.

It was the beginning of the arson campaign organised by the Women's Social Political Union. Railway stations, cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire. Slogans in favour of women's suffrage were cut and burned into the turf. Suffragettes also cut telephone wires and destroyed letters by pouring chemicals into post boxes. The women responsible were often caught and once in prison they went on hunger-strike. Determined to avoid these women becoming martyrs, the government introduced the Prisoner's Temporary Discharge of Ill Health Act. Suffragettes were now allowed to go on hunger strike but as soon as they became ill they were released. Once the women had recovered, the police re-arrested them and returned them to prison where they completed their sentences. This successful means of dealing with hunger strikes became known as the Cat and Mouse Act.

which are so different from those of your poor, misguided sister who I can't tolerate at all."

Joseph Morewood Staniforth, Western Mail (1913)

On this day in 1917 Edward Thomas is killed on the Western Front. Edward Thomas, the son of a civil servant from Wales, was born in London on 3rd March, 1878. After his education at St. Paul's School and Lincoln College, Oxford, Thomas became a writer of reviews and topographical works. His first book, The Woodland Life, was published in 1897.

In 1909 Thomas published a biography of Richard Jefferies, the writer and naturalist. Other books by Thomas included The Heart of England (1906), The South Country (1909), The Icknield Way (1913) and the novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913).

In the summer of 1915 Thomas enlisted as a private in the Artists' Rifles. The following year he was made a junior officer and transferred to the Royal Artillery. Lieutenant Edward Thomas began writing war poetry in 1915 but only a couple of these were published before he was killed by an exploding shell at Arras on 9th April, 1917.

After the war, his wife, Helen Thomas wrote about their relationship in As it Was (1926) and World Without End (1931). Their daughter, Myfanwy Thomas, also published her autobiography, One of These Fine Days (1982).

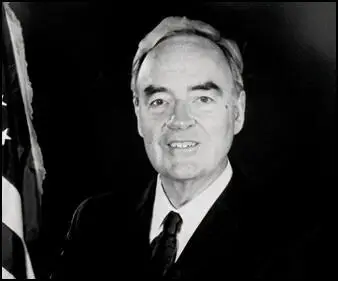

On this day in 1926 civil rights campaigner, Harris Wofford, was born in New York City. While at school he read Union Now, a book written by Clarence Streit, that advocated world government. As a result he established the Student Federalists organisation.

Wofford served in the United States Army Air Forces during the Second World War. After graduating from the University of Chicago (1948) and Howard University Law School (1954) he became a lawyer. Wofford was legal assistant, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1954-1958) before becoming a law professor at University of Notre Dame (1959-1960).

Wofford was an early supporter of the Civil Rights movement in the Deep South in the late 1950s and became a friend and unofficial advisor to Martin Luther King. King told Wofford that he would rather live one day as a lion than a thousand years as a lamb. In 1957 Wofford arranged for King to visit India. According to Coretta King, after this trip her husband "constantly pondered how to apply Gandhian principles in America." Wofford also helped King write Stride Toward Freedom (1958). The book described what happened during the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott and explained King's views on non-violence and direct action. The book was to have a considerable influence on the civil rights movement.

In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of black students read the book and decided to take action themselves. They started a student sit-in at the restaurant of their local Woolworth's store which had a policy of not serving black people. In the days that followed they were joined by other black students until they occupied all the seats in the restaurant. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of King they did not hit back.

Wofford was involved in negotiations with John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon during the 1960 Presidential Campaign. He later recalled: "He (King) was impressed and encouraged by the far-reaching Democratic civil rights platform, and preferred to use the campaign period to negotiate civil rights commitments from both candidates, but particularly from Kennedy."

After his election victory John Kennedy appointed his brother Robert F. Kennedy as Attorney General. Wofford was appointed as as his Special Assistant for Civil Rights. Wofford also served as chairman of the Subcabinet Group on Civil Rights. Soon after Kennedy was elected the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) began to organize Freedom Rides in an attempt to bring an end to segregation in transport. After three days of training in non-violent techniques, black and white volunteers sat next to each other as they travelled through the Deep South.

James Farmer, national director of CORE, and thirteen volunteers left Washington on 4th May, 1961, for Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Governor James Patterson commented that: "The people of Alabama are so enraged that I cannot guarantee protection for this bunch of rabble-rousers." Patterson, who had been elected with the support of the Ku Klux Klan added that integration would come to Alabama only "over my dead body."

The Freedom Riders were split between two buses. They travelled in integrated seating and visited "white only" restaurants. When they reached Anniston on 14th May the Freedom Riders were attacked by men armed with clubs, bricks, iron pipes and knives. One of the buses was fire-bombed and the mob held the doors shut, intent on burning the riders to death.

The surviving bus travelled to Birmingham, Alabama. A meeting of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee decided to send reinforcements. This included John Lewis, James Zwerg, and eleven others including two white women. The volunteers realized their mission was extremely dangerous. Zwerg later recalled: "My faith was never so strong as during that time. I knew I was doing what I should be doing." Zwerg wrote a letter to his parents that stated that he would probably be dead by the time they received it.

During the Freedom Riders campaign Robert Kennedy was phoning Jim Eastland “seven or eight or twelve times each day, about what was going to happen when they got to Mississippi and what needed to be done. That was finally decided was that there wouldn’t be any violence: as they came over the border, they’d lock them all up.” When they were arrested Kennedy issued a statement as Attorney General criticizing the activities of the Freedom Riders.

Kennedy sent John Seigenthaler to negotiate with Governor James Patterson of Alabama. Harris Wofford, later pointed out: "Seigenthaler arrived in time to escort the first group of wounded and shaken riders from the bus terminal to the airport, and flew with them to safety in New Orleans." The Freedom Riders now traveled onto Montgomery. One of the passengers, James Zwerg, later recalled: "As we were going from Birmingham to Montgomery, we'd look out the windows and we were kind of overwhelmed with the show of force - police cars with sub-machine guns attached to the backseats, planes going overhead... We had a real entourage accompanying us. Then, as we hit the city limits, it all just disappeared. As we pulled into the bus station a squad car pulled out - a police squad car. The police later said they knew nothing about our coming, and they did not arrive until after 20 minutes of beatings had taken place. Later we discovered that the instigator of the violence was a police sergeant who took a day off and was a member of the Klan. They knew we were coming. It was a set-up."

The passangers were attacked by a large mob. They were dragged from the bus and beaten by men with baseball bats and lead piping. Taylor Branch, the author of Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (1988) wrote: "One of the men grabbed Zwerg's suitcase and smashed him in the face with it. Others slugged him to the ground, and when he was dazed beyond resistance, one man pinned Zwerg's head between his knees so that the others could take turns hitting him. As they steadily knocked out his teeth, and his face and chest were streaming blood, a few adults on the perimeter put their children on their shoulders to view the carnage." Zwerg later argued: "There was noting particularly heroic in what I did. If you want to talk about heroism, consider the black man who probably saved my life. This man in coveralls, just off of work, happened to walk by as my beating was going on and said 'Stop beating that kid. If you want to beat someone, beat me.' And they did. He was still unconscious when I left the hospital. I don't know if he lived or died."

Some of the Freedom Riders, including seven women, ran for safety. The women approached an African-American taxicab driver and asked him to take them to the First Baptist Church. However, he was unwilling to violate Jim Crow restrictions by taking any white women. He agreed to take the five African-Americans, but the two white women, Susan Wilbur and Susan Hermann, were left on the curb. They were then attacked by the white mob.

John Seigenthaler, who was driving past, stopped and got the two women in his car. According to Raymond Arsenault, the author of Freedom Riders (2006): "Suddenly, two rough-looking men dressed in overalls blocked his path to the car door, demanding to know who the hell he was. Seigenthaler replied that he was a federal agent and that they had better not challenge his authority. Before he could say any more, a third man struck him in the back of the head with a pipe. Unconscious, he fell to the pavement, where he was kicked in the ribs by other members of the mob. Pushed under the rear bumper of the car, his battered and motionless body remained there until discovered by a reporter twenty-five minutes later."

Harris Wofford, pointed out: "Seigenthaler went to the defense of a girl being beaten and was clubbed to the ground; he was kicked while he lay there unconscious for nearly half an hour. Again FBI agents present did nothing, except take notes." Robert F. Kennedy later reported: "I talked to John Seigenthaler in the hospital and said that I thought it was very helpful for the Negro vote, and that I appreciated what he had done."

The Ku Klux Klan hoped that this violent treatment would stop other young people from taking part in freedom rides. However, over the next six months over a thousand people took part in freedom rides. With the local authorities unwilling to protect these people, President John F. Kennedy sent Byron White and 500 federal marshals from the North to do the job.

Robert Kennedy petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to draft regulations to end racial segregation in bus terminals. The ICC was reluctant but in September 1961 it issued the necessary orders and it went into effect on 1st November. However, James Lawson, one of the Freedom Riders, argued: "We must recognize that we are merely in the prelude to revolution, the beginning, not the end, not even the middle. I do not wish to minimize the gains we have made thus far. But it would be well to recognize that we have been receiving concessions, not real changes. The sit-ins won concessions, not structural changes; the Freedom Rides won great concessions, but not real change."

Robert Kennedy admitted to Anthony Lewis that he had come to the conclusion that Martin Luther King was closely associated with members of the American Communist Party and he asked J. Edgar Hoover “to make an intensive investigation of him, to see who his companions were and also to see what other activities he was involved in… They made that intensive investigation, and I gave them also permission to put a tap on his phone.”

Hoover reported to Kennedy that Wofford was a “Marxist” and that he was very close to Stanley Levison, who was a “secret member of the Executive Committee of the Communist Party”. Hoover informed King that Levison, who was a legal adviser to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was a member of Communist Party. However, when King refused to dismiss Levison, the Kennedys became convinced that King was himself a communist.

John F. Kennedy agreed to move Harris Wofford in April 1962. Robert F. Kennedy told Anthony Lewis: “Harris Wofford was very emotionally involved in all these matters and was rather in some areas a slight madman. I didn’t want to have someone in the Civil Rights Division who was dealing not from fact but was dealing from emotion… I wanted advice and ideas from somebody who had the same interests and motivation that I did.” Wofford became the Peace Corps Special Representative for Africa. Later he was appointed as Associate Director of the Peace Corps.

Wofford also served as president of the College at Old Westbury (1966-1970) and Bryn Mawr College (1970-1978). In 1980 he published Of Kennedys and Kings. The book provides an insiders view of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Lyndon B. Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, McGeorge Bundy, Dean Rusk, Robert S. McNamara, Theodore Sorenson and other leading political figures in the 1960s.

A member of the Democratic Party, Wofford was Pennsylvania secretary of labor and industry (1987-1991). On 4th April, 1991, Pennsylvania's U.S. Senator, John Heinz, died in an aviation accident leaving his seat in the U.S. Senate open. In the special election held in November 1991, Wofford defeated Dick Thornburgh. The following year he was considered for the vice presidential nomination, although Bill Clinton ultimately chose Al Gore.

Wofford narrowly lost his 1994 bid for re-election to Rick Santorum, 49%-47%. His support for a federal ban on semi-automatic firearms also cost him significant support throughout the state. In October 1995 he was appointed Chief Executive Officer of the Corporation for National and Community Service. A post he held to January 2001.

Harris Wofford died on 21st January, 2019.

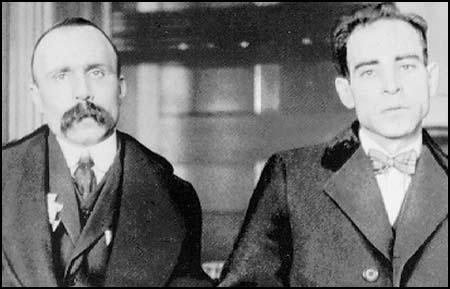

On this day in 1927 Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti are sentenced to death. On 5th May, 1920, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested and interviewed about the murders of Frederick Parmenter and Alessandro Berardelli, in South Braintree. The men had been killed while carrying two boxes containing the payroll of a shoe factory. After Parmenter and Berardelli were shot dead, the two robbers took the $15,000 and got into a car containing several other men, and driven away.

Several eyewitnesses claimed that the robbers looked Italian. A large number of Italian immigrants were questioned but eventually the authorities decided to charge Sacco and Vanzetti with the murders. Although the two men did not have criminal records, it was argued that they had committed the robbery to acquire funds for their anarchist political campaign.

Fred H. Moore, a socialist lawyer, agreed to defend the two men. Eugene Lyons, a young journalist, carried out research for Moore. Lyons later recalled: "Fred Moore, by the time I left for Italy, was in full command of an obscure case in Boston involving a fishmonger named Bartolomeo Vanzetti and a shoemaker named Nicola Sacco. He had given me explicit instructions to arouse all of Italy to the significance of the Massachusetts murder case, and to hunt up certain witnesses and evidence. The Italian labor movement, however, had other things to worry about. An ex-socialist named Benito Mussolini and a locust plague of blackshirts, for instance. Somehow I did get pieces about Sacco and Vanzetti into Avanti!, which Mussolini had once edited, and into one or two other papers. I even managed to stir up a few socialist onorevoles, like Deputy Mucci from Sacco's native village in Puglia, and Deputy Misiano, a Sicilian firebrand at the extreme Left. Mucci brought the Sacco-Vanzetti affair to the floor of the Chamber of Deputies, the first jet of foreign protest in what was eventually to become a pounding international flood."