On this day on 4th January

On this day in 1642 King Charles I sent his soldiers to the House of Commons to arrest John Pym, Arthur Haselrig, John Hampden, Denzil Holles and William Strode. The five men managed to escape before the soldiers arrived. Members of Parliament no longer felt safe from Charles and decided to form their own army. After failing to arrest the Five Members, Charles fled from London and formed a Royalist Army (Cavaliers) whereas his opponents established a Parliamentary Army (Roundheads).

Attempts were made to negotiate and end to the conflict. On 25th July the king wrote to the vice-chancellor of Cambridge University inviting the colleges to assist him in his struggle. When they heard the news, the House of Commons sent Oliver Cromwell with 200 lightly armed countrymen to blocked the exit road from Cambridge. On 22nd August, the king "raised his standard" at Nottingham, and in doing so marked the beginning of the English Civil War.

On this day in 1807 Elizabeth Pease, the daughter of Joseph Pease and Elizabeth Beaumont Pease, was born in Darlington. Her father was a wool manufacturer and along with his wife were Quakers who played a leading role in philanthropic and humanitarian movements. Elizabeth was educated at a local school and then by a governess, but her studies were disrupted by nursing her sick mother who died in 1824.

Elizabeth came from a family heavily involved in the struggle for social reform. She was related to Isabella Ford and was close to Harriet Martineau. Elizabeth worked as her father's secretary in the campaign's for Catholic Emancipation, abolition of the Test Acts and the struggle against slavery.

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

William Wilberforce and other leaders of the Anti-Slavery Society were upset by Heyrick's views and attempts were made to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet. Wilberforce's biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

Elizabeth Pease and most of the women involved in the campaign against slavery agreed with Heyrick. Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture".

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

Elizabeth Pease formed a women's group in Darlington. Other groups were established in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery.

She supported the campaign for the 1832 Reform Act which enabled Joseph Pease, to become Britain's first Quaker member of the House of Commons. However, unlike most middle-class reformers, Elizabeth was not satisfied with this measure and along with her close friend, Anne Knight, became a supporter of the campaign for universal suffrage.

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed on 28th August 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned.

Pease joined forces with her friend Jane Smeal of Glasgow to campaign for universal suffrage. Smeal pointed out: "The females in this city who have much leisure for philanthropic objects are I believe very numerous - but unhappily that is not the class who take an active part in the cause here - neither the noble, the rich, nor the learned are to be found advocating our cause. Our subscribers and most efficient members are all in the middling and working classes but they have great zeal and labour very harmoniously together."

In March 1838, Elizabeth and Jane Smeal published a pamphlet, Address to the Women of Great Britain, where they urged women to organise female political associations. She fostered links between female anti-slavery societies in Britain and the United States, and she became one of the leading British promoters of the radical wing of the movement which was led by William Lloyd Garrison. Pease also engaged in an extensive correspondence with American abolitionists.

Elizabeth Pease attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention held at Exeter Hall in London, in June 1840 but as a woman was refused permission to speak. However, she did take the opportunity to meet American abolitionists, such as Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Mott later commented that Pease was "a fine noble-looking girl".

Anne Knight became aware that the artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, had started a group portrait of those involved in the fight against slavery. She wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend complaining about the lack of women in the painting. "I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement."

When the painting was completed it did include Elizabeth Pease. Clare Midgley, the author of Women Against Slavery (1995) points out that it also featured Mary Anne Rawson, Amelia Opie and Annabella Byron: "Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right."

Elizabeth Pease was a great advocate of women becoming involved in politics. She wrote to her friend, John Collins: "I believe there are few persons whose natural feelings are so opposed to women appearing prominently before the public, as mine - but viewed in the light of principle I see, the prejudice - custom and other feelings which will not stand the test of truth, are at the bottom, and must be laid aside."

In 1842 Elizabeth Pease became a Chartist: "I believe the Chartists generally hold the doctrine of the equality of women's rights - but, I am not sure whether they do not consider that when she marries, she merges her political rights with those of her husband." She argued passionately for social reform: "The grand principle of the natural equality of man - a principle alas almost buried, in the land, beneath the rubbish of an hereditary aristocracy and the force of a state religion. Working people are driven almost to desperation by those who consider they are but chattels made to minister to their luxury and add to their wealth."

Elizabeth Pease married Dr John Pringle Nichol, regius professor of astronomy at the University of Glasgow on 6th July 1853. He was a Presbyterian, and Elizabeth was disowned by the Society of Friends for "marrying out". Pease left the family home in Darlington to live with her husband in Glasgow until his death in 1859. Elizabeth was a member of the Peace Society and the Temperance Society also took part in the anti-vivisection campaign. She publicly supported women's struggle to gain medical training at Edinburgh University; she became a member of the Edinburgh committee of the Ladies' Educational Association.

In February 1880 Elizabeth was present at the Great Demonstration of Women at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. She pointed out that some of her friends considered her to be "ungenteel" and "vulgar" because she was a supporter of universal suffrage. Elizabeth also signed the "Letter from Ladies to Members of Parliament", asking for the inclusion of women heads of householders in the 1884 Reform Act.

Elizabeth Pease Nichol, died aged 90, on 3rd February 1897 at her home, Huntly Lodge, in Edinburgh, and was buried on 8th February alongside her husband in Grange Cemetery.

showing from left to right, bottom row: Annabella Byron, Amelia Opie,

Mary Anne Rawson, top row, Anne Knight, Mrs John Beaumont and Elizabeth Pease.

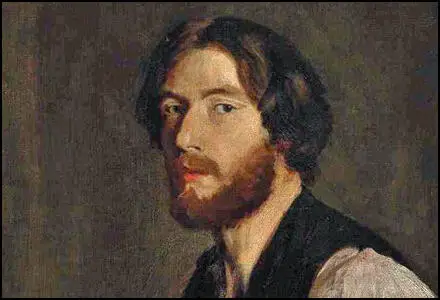

On this day in 1878 Augustus John, the third of the four children of Edwin William John (1847–1938), and his wife, Augusta Smith (1848–1884), was born in Tenby on 4th January 1878. His father was a solicitor and her mother, an amateur artist. His sister, Gwen John, had been born in 1876. His mother died of rheumatic gout when he was only six years old.

Michael Holroyd has argued: "Queen Victoria had gone into perpetual mourning after Prince Albert's death in 1861, and Edwin, who never remarried and who in his late thirties retired from practising as a solicitor, seems to have felt it proper to follow her example within the dark interior of Victoria House. The atmosphere in which his two sons and two daughters grew up was loveless and claustrophobic." Their father had cautioned his children never to go out on market days in case they were captured by the Gypsies. John told his friend, Nina Hamnett: "We are the sort of people our fathers warned us against!"

Augustus John went to the local Greenhill School before being sent to a boarding school in Clifton near Bristol. He also received drawing lessons from a local artist and in 1894 he went to the Slade School of Art. Augustus was taught by Henry Tonks, Philip Wilson Steer and Frederick Brown. Other students at the Slade at the time included William Orpen, Wyndham Lewis. Spencer Gore, Michel Salaman, Edna Waugh, Herbert Barnard Everett, Albert Rothenstein, Ambrose McEvoy, Ursula Tyrwhitt, Ida Nettleship and Gwen Salmond.

After injuring his head after diving into the sea while on holiday in 1895 his personality changed. He grew a beard, dressed as a Bohemian and drank heavily. His painting became more adventurous and his friend, Wyndham Lewis remarked that John had become a "great man of action into whose hands the fairies had placed a paintbrush instead of a sword". Considered to be the most talented artist of his generation, in 1898 John won the Slade Prize with Moses and the Brazen Serpent. He developed a nomadic lifestyle and for a while he lived in a caravan and camped with gypsies.

Augustus John was joined by Gwen John at the Slade School of Art. He later wrote: "It wasn't long before my sister Gwen joined me at the Slade. She wasn't going to be left out of it! We shared rooms together, subsisting, like monkeys, on a diet of fruit and nuts. This was cheap and hygienic. It is true we were sometimes asked out to dinner, when, not being pedants, we waived our rule for the time being."

William Rothenstein took a keen interest in the work of young artists. This included Augustus John who wrote in his autobiography, Chiaroscuro: "Encouraged by Will Rothenstein, I held my first show at the newly established Carfax Gallery, Ryder Street, St. James's... My little show was a success. I made thirty pounds. With this sum in my pocket there was nothing to prevent me joining Will Rothenstein, Orpen and Charles Conder in France. Rothenstein had found a good spot not far from Étretat on the Normandy coast."

John later recalled his time with Charles Conder in France: "Conder was a charming personality. He spoke in an exhausted and muffled voice, which made it difficult sometimes to follow him with intelligence. A lock of brown hair always hung over one malicious blue eye. Though his ordinary gait could be described with some accuracy as a shuffle, given a sufficient incentive he was capable of great speed and endurance."

In 1898 Augustus John, Charles Conder and William Rothenstein went to Paris to visit Oscar Wilde. John later recalled: "I had heard a lot about Oscar, of course, and on meeting him was not in the least disappointed, except in one respect: prison discipline had left one, and apparently only one, mark on him, and that not irremediable: his hair was cut short... We assembled first at the Cafe de la Regence.... The Monarch of the dinner-table seemed none the worse for his recent misadventures and showed no sign of bitterness, resentment or remorse. Surrounded by devout adherents, he repaid their hospitality by an easy flow of practised wit and wisdom, by which he seemed to amuse himself as much as anybody. The obligation of continual applause I, for one, found irksome. Never, I thought, had the face of praise looked more foolish."

Augustus John was the subject of his painting, The Dolls House (1900). He later wrote: "It was at Vattetot that William Rothenstein painted The Doll’s House for which Alice Rothenstein and I posed. This is a regular problem picture. I am portrayed standing at the foot of a staircase upon which Alice has un accountably seated herself. I appear to be ready for the road, for I am carrying a mackintosh on my arm and am shod and hatted. But Alice seems to hesitate. Can she have changed her mind at the last moment? But what could have been her intention? Perhaps the weather had changed for the worse and made a promenade inadvisable: but we shall never know. The picture will remain a perpetual enigma, to disturb, fascinate or repel".

On 24th January 1901 Augustus John married Ida Nettleship (1877–1907). For the first eighteen months of their marriage they lived in Liverpool, where John had taken a post teaching at a local art school. In 1902 the couple had their first son, David Anthony Nettleship. He also joined the New English Art Club.

In March 1903 Augustus John and Gwen John had a joint exhibition at Carfax & Company. However, she worked very slowly and contributed only three pictures to her brother's forty-five. Michael Williams has argued: "Their relationship was non-competitive and highly affectionate. Although critical of Gwen’s evident unconcern about her health, Augustus was foremost in appreciating her art. What his own work owed in technical mastery, he felt that Gwen’s pictures more than compensated in interior feeling and expressiveness."

Later that year Augustus John founded, with William Orpen as co-principal, the Chelsea Art School in Rossetti Mansions. He also became involved with Dorelia McNeill. According to Michael Holroyd: "She became his femme inspiratrice and the subject of many of his best-known pictures... Few people seeing this emphatic and unbuttoned model, whose enigmatic smile was likened by critics to that of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, would have guessed that she was a simple person of humble origins."

Augustus continued to live with Ida Nettleship and she gave birth to Casper (1903), Robin (1904), Edwin (1905), and Henry (1907). With Dorelia he had Pyramus (1905) and Romilly (1906). Ida died in 1907 from puerperal fever. Later, Dorelia gave birth to another son, Vivien. In 1911 the family moved in with Henry Lamb at Alderney Manor near Poole.

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, John was the best-known artist in Britain. His friendship with Lord Beaverbrook enabled him to obtain a commission in the Canadian Army and was given permission to paint what he liked on the Western Front. He was also allowed to keep his facial hair and therefore became the only officer in the Allied forces, except for King George V, to have a beard. After two months in France he was sent home in disgrace after taking part in a brawl.

Lord Beaverbrook, whose intervention saved John from a court-martial, sent him back to France but is only known to have completed one painting, Fraternity. John also attended the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919 where he painted the portraits of several delegates. However, the commissioned group portrait of the main figures at the conference was never finished.

By the 1920s John was Britain's leading portrait painter. Those who sat for him included Thomas Hardy, George Bernard Shaw, Ottoline Morrell, T. E. Lawrence, Jacob Epstein, Wyndham Lewis, W. B. Yeats, William Nicholson, and Dylan Thomas. However, one critic has claimed that "the painterly brilliance of his early work degenerated into flashiness and bombast, and the second half of his long career added little to his achievement."

His biographer, Michael Holroyd, has argued: "From the late 1920s onwards John's talent went into a decline which, despite a number of journeys he made through Europe, Jamaica, and the United States seeking to revive it, was accelerated by his heavy drinking. The rebel artist had now moved from the roadside into London's West End where his work was irregularly exhibited from 1929 to 1961 at Dudley Tooth's gallery in Bruton Street." Anthony Blunt has claimed: "Everyone is agreed on the fact that Augustus John was born with a quite exceptional talent - some even use the word genius and almost everyone is agreed that he has in some way wasted it".

In later life, Augustus John wrote two volumes of autobiography, Chiaroscuro and Finishing Touches. He also took an interest in politics as he got older and as a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, took part in a demonstration on 17th September 1961. Aged 83, he had been seriously ill but was determined to join the other protesters in Trafalgar Square. Augustus John died of heart failure at his home at Fryern Court in Fordingbridge on 31st October 1961.

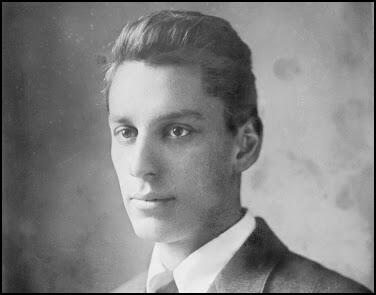

On this day in 1883 Max Eastman was born in Canandaigua. Both his parents, Samuel Eastman and Annis Ford, were church ministers. In 1889 his mother was one of the first women to be ordained as a minister. Eastman graduated from Williams College in 1905 and afterwards studied philosophy with John Dewey at Columbia University.

Barbara Gelb has argued: "The son of two Congregational ministers from upstate New York, Eastman had been raised in an atmosphere of liberal-mindedness; having a mother who was the first woman to be ordained a Congregational minister in New York State, Eastman found himself perfectly at home in sympathy with the suffragists and other social reform movements of the day."

In 1907 Eastman moved to New York City, settling in Greenwich Village with his sister Crystal Eastman. Soon afterwards Eastman met Ida Rauh. According to William L. O'Neill: "Ida Rauh, a beautiful and intelligent Jewish woman with a private income, whom Max Eastman had known since first coming to New York. She was rebelling against her bourgeois family and explained the class struggle to him so clearly that he became a socialist." Eastman was persuaded to join the Men's League for Women's Suffrage.

The couple were married on 4th May, 1911 in Patterson, New Jersey. He later recalled that he awoke the next morning seized with terror: "I had lost, in marrying Ida, my irrational joy in life." The author of The Last Romantic (1978), has argued: "Unlike his affectionate mother and sister, Ida was never one to shower people, even her husband, with compliments and attentions. Yet these were necessary to Max's well-being. She was given to periods of indolence and so could not pour vitality into Max's languid nerves as he thought essential."

Sidney Hook got to know Eastman during this period. He later recalled: "Max Eastman was authentically American, sympathetic to the great rebels of the American past, intellectually independent, drawn to an undogmatic socialism on compassionate rather than economic grounds, an ardent supporter of women's rights at a time when it was dangerous even for a woman to be known as a feminist, defender of dissemination of information about birth control, an advocate of free love and open marriage, a pioneer for civil liberties, receptive to new ideas in almost every field. Max Eastman fought in more good causes than almost any man or woman of his generation, and yet he was by no means a purely literary radical - one of those who flaunt their radical ideas but never come within hailing distance of any political activity. Eastman put his very life and career on the line in pursuit of his radical ideas. More than once he had the courage to stand up to an enraged mob."

Eastman developed a reputation as an outstanding journalist and in 1912 was invited to become editor of the left-wing magazine, The Masses. Organized like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. Other radical writers and artists who joined the team included Floyd Dell, John Reed, William Walling, Crystal Eastman, Sherwood Anderson, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Arturo Giovannitti, Michael Gold, Amy Lowell, Louise Bryant, John Sloan, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers."

Floyd Dell was appointed as Eastman's assistant: "Max Eastman was a tall, handsome, poetic, lazy-looking fellow... I was paid twenty-five dollars a week for helping Max Eastman get out the magazine.... At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists."

The Masses was often in trouble with the authorities. One of Art Young's cartoons, Poisoned at the Source, that appeared in the July 1913 edition of the magazine upset the Associated Press company and he was indicted for criminal libel. However, after a year, the company decided to drop the law suit.

Max Eastman, like most of the people working for The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in the fact that the articles and cartoons that appeared in journal attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of Dell and his fellow defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

In 1918 Eastman joined with Art Young, Floyd Dell and his sister, Crystal Eastman, to establish another radical journal, The Liberator. Other writers and artists involved in the magazine included Claude McKay, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, Maurice Becker, Helen Keller, Cornelia Barns, and William Gropper.

In 1922 the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the Communist Party and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. After this Eastman left the United States and travelled to the Soviet Union. Eastman had welcomed the Russian Revolution but became disillusioned when Joseph Stalin ousted Leon Trotsky.

Eastman divorced his first wife, Ida Raub, to marry Elena Krylenko in 1924. He met her during a visit to the Soviet Union. Elena's brother, was Nikolai Krylenko, who, as president of the supreme tribunal he prosecuted all the major political trials of the 1920s. Later, Joseph Stalin appointed Krylenko as Commissar for Justice and was involved in the conviction of a large number of members of the Communist Party during the Great Purges.

Eastman went to live in France in 1924 where he wrote Since Lenin Died (1925), and Marx and Lenin: The Science of Revolution (1926). In these books Eastman warned of the dangers posed by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. The book was unpopular with most American Marxists and Eastman was denounced as a rebellious individualist. Sidney Hook argued: "Of all the forms of intellectual independence Eastman displayed in his life, nothing matched the courage he had to summon up when he stood practically alone on his return from the Soviet Union in 1924. He had brought with him the first hard evidence of the Stalinization of the Bolshevik regime. In consequence, he became a rebel outcast in his own country and a pariah in the radical movement that had been central to his life."

In 1927 Eastman returned to the United States and now a supporter of Leon Trotsky, becomes his translator and unofficial literary agent. During the Great Purge most of Eastman's left-wing friends in the Soviet Union were executed by Stalin. Books published during this period include The Enjoyment of Laughter (1935), The End of Socialism in Russia (1937), Stalin's Russia and the Crisis in Socialism (1940), Marxism, Is It Science? (1940) and Heroes I Have Known (1942).

During the Second World War Eastman began to question his socialist beliefs. In 1941 the Reader's Digest appointed him their roving editor and began publishing his attacks on socialists and communists. He wrote: "Red Baiting - in the sense of reasoned, documented exposure of Communist and pro-Communist infiltration of government departments and private agencies of information and communication - is absolutely necessary. We are not dealing with honest fanatics of a new idea, willing to give testimony for their faith straightforwardly, regardless of the cost."

In 1952 Eastman was introduced to Alexander Orlov, a NKVD officer who had fled to the United States in 1938. Orlov had been working on a book about Joseph Stalin. Eastman agreed to be his literary agent. Eastman arranged for Orlov to meet Eugene Lyons, another former Marxist who was now a staunch anti-Communist. This led to a meeting with John S. Billings, the editor of Life Magazine. Orlov submitted his manuscript to the magazine and the first of the four articles, The Ghastly Secrets of Stalin's Power, appeared on 6th April. The article created great controversy and was discussed in great depth in the American media. With each successive installment, the circulation of the magazine reached new heights. Orlov's book, The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes, was published by Random House in the autumn of 1953.

In the 1950s Max Eastman was a strong supporter of Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). His anti-Communist articles in the Reader's Digest, The Freeman and the National Review in the early 1950s played an important role in what became known as McCarthyism. In June 1953 he wrote: "Red Baiting - in the sense of reasoned, documented exposure of Communist and pro-Communist infiltration of government departments and private agencies of information and communication - is absolutely necessary. We are not dealing with honest fanatics of a new idea, willing to give testimony for their faith straightforwardly, regardless of the cost. We are dealing with conspirators who try to sneak in the Moscow-inspired propaganda by stealth and double talk, who run for shelter to the Fifth Amendment when they are not only permitted but invited and urged by Congressional committee to state what they believe. I myself, after struggling for years to get this fact recognized, give McCarthy the major credit for implanting it in the mind of the whole nation."

In 1955 he published Reflections on the Failure of Socialism. He argued: "Instead of liberating the mind of man, the Bolshevik revolution locked it into a state's prison tighter than ever before. No flight of thought was conceivable, no poetic promenade even, to sneak through the doors or peep out of a window in this pre-Darwinian dungeon called Dialectic Materialism. No one in the western world has any idea of the degree to which Soviet minds are closed and sealed tight against any idea but the premises and conclusions of this antique system of wishful thinking. So far as concerns the advance of human understanding, the Soviet Union is a gigantic road-block, armed, fortified and defended by indoctrinated automatons made out of flesh, blood and brains in robot-factories they call schools."

In 1956 Eastman wrote: "We are fighting this cold war for our life, and we must fight on all fronts and in every field of action. We must employ in a campaign to liberate the enslaved countries and deliver the world from the menace of Communist tyranny all the means employed by the Communists to destroy and enslave us-expecting only that we fight with the truth, adhering to moral principle, while they fight with lies and a deliberate code of treachery. And we must make our aim as clear to the world as the Communists have made theirs. We must never affirm our loyalty to Peace without linking to it the word Freedom."

For over twenty-five years Eastman worked as a roving reporter for the Reader's Digest where he advocated free enterprise and warned of the dangers of communism. He also wrote two volumes of autobiography: The Enjoyment of Living (1948) and Love and Revolution (1965). Max Eastman died at his summer home in Bridgetown, Barbados, at the age of 86, on 25th March, 1969.

On this day in 1884 the Fabian Society is founded in London. In October 1883 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland decided to form a socialist debating group with their Quaker friend Edward Pease. They were also joined by Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles.

Hubert Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. By March 1884 the group had twenty members. In April 1884 Edith Nesbit wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

George Bernard Shaw joined the Fabian Society in August 1884. Nesbit wrote: "The Fabian Society is getting rather large now and includes some very nice people, of whom Mr. Stapelton is the nicest and a certain George Bernard Shaw the most interesting. G.B.S. has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

Over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Edith Lees, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Charles Trevelyan, John Clifford, Arthur Ransome, Cecil Chesterton, Ada Chesterton, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Edward Carpenter, Clement Attlee, Ramsay MacDonald, Emmeline Pankhurst,Walter Crane, Arnold Bennett, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Hugh Dalton, C. E. M. Joad, Rupert Brooke, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

Early talks at the Fabian Society included: How Can We Nationalise Accumulated Wealth by Annie Besant, Private Property by Edward Carpenter, The Economics of a Postivist Community by Sidney Webb and Personal Duty under the Present System by Graham Wallas.

In 1886 Frank Podmore and Sidney Webb carried out an investigation into unemployment. In the Fabian Society pamphlet, The Government Organisation of Unemployed Labour they advocated the funding of rural land armies but declined to endorse large-scale public employment as they feared it would encourage inefficiency.

By 1886 the Fabians had sixty-seven members and an income of £35 19s. The official headquarters of the organisation was 14 Dean's Yard, Westminster, the home of Frank Podmore. The Fabian Society journal, Today, was edited by Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland.

The Fabians believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. They agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". The Fabians rejected the revolutionary socialism of H. M. Hyndman and the Social Democratic Federation and were concerned with helping society to move to a socialist society "as painless and effective as possible".

The Fabians adopted the tactic of trying to convince people by "rational factual socialist argument", rather than the "emotional rhetoric and street brawls" of the Social Democratic Federation. The Fabian group was a "fact-finding and fact-dispensing body" and they produced a series of pamphlets on a wide variety of different social issues.

In 1889 the Fabian Group decided to publish a book that would provide a comprehensive account of the organisations's beliefs. Fabian Essays in Socialism included chapters written by George Bernard Shaw, Sydney Webb, Annie Besant, Sydney Olivier, Graham Wallas, William Clarke and Hubert Bland. Edited by Shaw, the book sold 27,000 copies in two years.

William Morris, a former member of the Social Democratic Federation, and founder of the Socialist League, strongly criticised the Fabian Essays in the journal Commonweal. Morris disagreed with what he called "the fantastic and unreal tactic" of permeation which "could not be carried out in practice, and which, if it could be, would still leave us in a position from which we should have to begin our attack on capitalism over again".

The success of Fabian Essays in Socialism (1889) convinced the Fabian Society that they needed a full-time employee. In 1890 Edward Pease was appointed as Secretary of the Society. His duties included keeping the minutes at meetings, dealing with the correspondence, arranging lecture schedules, managing the Fabian Information Bureau, circulating book-boxes and editing and contributing to the Fabian News.

In 1890 Henry Hutchinson, a wealthy solicitor from Derby, decided to give the Fabian Society £200 a year to spend on public lectures. Some of this was used to pay Fabian members such as Harry Snell, Ramsay MacDonald, Graham Wallas, Catherine Glasier and Bruce Glasier to travel around the country giving lecturers on subjects such as 'Socialism', 'Trade Unionism', 'Co-operation' and 'Economic History'.

Hutchinson died four years later leaving the Fabian Society £10,000. Hutchinson left instructions that the money should be used for "propaganda and socialism". Hutchinson selected his daughter as well as Edward Pease, Sidney Webb, William Clarke and W. S. De Mattos as trustees of the fund, and together they decided the money should be used to develop a new university in London. The London School of Economics (LSE) was founded in 1895. As Sidney Webb pointed out, the intention of the institution was to "teach political economy on more modern and more socialist lines than those on which it had been taught hitherto, and to serve at the same time as a school of higher commercial education".

The Webbs first approached Graham Wallas, now one of the most prominent members of the Fabians, to become the Director of the LSE. Wallas agreed to lecture there but declined the offer as director, and W. A. S. Hewins, a young economist at Pembroke College, Oxford, was appointed instead. With the support of the London County Council (LCC) the LSE flourished as a centre of learning.

On 27th February 1900, Edward Pease represented the Fabian Society at the meeting of socialist and trade union groups at the Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street, London. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour."

To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists. Some members of the Fabian Society had doubts about this and Edward Pease personally paid the affiliation dues.

In 1912 Beatrice Webb established he Fabian Research Department. Its first secretary was Robin Page Arnot. He was later replaced by William Mellor. As Paul Thompson pointed out in his book, Socialist, Liberals and Labour (1967): "Its secretary was William Mellor and another leading member G. D. H. Cole, both young Oxford Fabians and both Guild Socialists. Together in April 1913 and March 1914 they led two attempts to disaffiliate the Fabian Society from the Labour Party. They failed, but when Cole resigned in 1915 he was able to take the Research Department with him, thus depriving the Fabian Society of its most talented younger members and resulting in its subsequent stagnation in the 1920s."

On this day in 1891 Lilian Lenton, the eldest daughter of Isaac Lenton (1867-1930) and his wife Mahala Bee Lenton (1864-1920), was born in Leicester on 5th January 1891.Her father was a carpenter-joiner and her mother worked in a glove factory.

Lenton later wrote: "In those days I was extremely annoyed at the difference between a boy and a girl. And when I grew up and saw the opportunities that boys had, and those that girls and women hade, of course that just increased the feeling. Why should God be male? That was one thing that always struck me."

After leaving school Lenton trained to be a dancer and took the name "Ida Inkley". A supporter of women's suffrage she heard Emmeline Pankhurst speak and later recalled that she "made up my mind that night that as soon as I was twenty-one and my own boss... I would volunteer" to get involved in the struggle for the vote and joined the Women's Social and Political Union.

On 4th March, 1912, window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. Lilian Lenton was one of the 200 suffragettes were arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration. She was found guilty and was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. After leaving prison she joined the campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, 1912, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The main figure in this campaign was May Billinghurst. Lenton recalled: "She (May Billinghurst) would set out in her chair with many little packages from which, when they were turned upside down, there flowed a dark brown sticky fluid, concealed under the rug which covered her legs. She went undeviatingly from one pillar box to another, sometimes alone, sometimes with another suffragette to do the actual job, dropping a package into each one."

In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst began organizing a secret arson campaign. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest."

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. During the trial, Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone."

Lenton claimed that she was one of the first people to join this group: "Well, I was at the Suffragette Headquarters and announced that I didn't want to break any more windows but I did want to burn some buildings, and I was told that a girl named Olive Wharry had just been in saying the same thing, so we two met, and the real serious fires in this country started and thereafter I was in and out of prison – six times I think it was – and whenever I was out of prison my object was to burn two buildings a week."

It has speculated that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Mary Richardson, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks. It would seem that Helen Craggs was the first to carry out an act of arson. On 13th July 1912 Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river . Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody.

Lilian Lenton explained: "Well, the object was to create an absolutely impossible condition of affairs in the country, to prove that it was impossible to govern without the consent of the governed. A few young men were very anxious to help us. But these young men only seemed to have one idea, and that was bombs. Now I don't like bombs. After all, the rule was that we must risk no-one's lives but our own, and if you take a bomb somewhere, however great the precautions, you can't be one hundred percent sure."

Lenton joined forces with Olive Wharry and embarked on a series of terrorist acts. She was arrested on 19th February 1913, soon after setting fire to the tea pavilion in Kew Gardens. In court it was reported: "The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry. In one of the bags which the women threw away were found a hammer, a saw, a bundle to tow, strongly redolent of paraffin and some paper smelling strongly of tar. The other bag was empty, but it had evidently contained inflammables."

A police report on her behaviour when arrested suggested that Lenton was a difficult prisoner: "Has been in prison before but refuses to give any particulars. General conduct: bad, very defiant. Refuses medical examination - Is rather spare (thin).... Recognised by officers as having been in prison before but name cannot be given. Has taken no food since reception. Smashed up everything in the cell she was first placed in. Removed to a special strong cell. Kept apart from all other prisoners & not allowed to communicate. All privileges suspended."

Lilian Lenton went on hunger-strike and was forcibly fed before being released on 23rd February, 1913. The case caused a great deal of controversy. Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, denied that she had been forcibly fed and her illness was due to the effects of her hunger strike. In reality, she had been fed by nasal tube and two hours later the prison doctor reported that he found her "in a very collapsed condition" and "remained for about two hours in a very critical condition".

Lenton's supporters sent a letter to The Times: "She (Lenton) was certainly in imminent danger of death on that Sunday afternoon, but this was not due to her two days' fast, but to the fact that during forcible feeding executed by the prison doctors on the Sunday morning food was poured into her lungs... The plain facts of Miss Lenton's case prove clearly that the food which was forcibly injected into her lung set up a pleuro-pneumonic condition which, but for her youth and good healthy physique, could have ended more seriously. That the prison doctor and the governor recognised immediately what they had done is also obvious. They hurriedly and at the further risk of injury to the patient immediately removed her from the prison, so that at least she should not die there and thus compromise the Home Office, and our horrible prison administration of which they were the instruments."

After she recovered Lenton managed to evade recapture until arrested in June 1913 in Doncaster and charged with setting fire to to a railway station at Blaby, Leicestershire. She was held in custody at Armley Prison in Leeds. She immediately went on hunger-strike and was released after a few days under the Cat & Mouse Act. The following month she escaped to France in a private yacht. Lenton was soon back in England setting fire to buildings but in October 1913 she was arrested at Paddington Station. Once again she went on hunger-strike and was forcibly fed, but once again she was released when she became seriously ill.

Lenton was released on licence on 15th October. She escaped from the nursing home and was arrested on 22nd December 1913 and charged with setting fire to a house in Cheltenham: "The two Suffragettes who, minus shoes and stockings, and with their hair falling on their shoulders, were charged at Cheltenham on Monday last week with setting fire to Alstone Lawn, an unoccupied mansion belonging to Colonel De Sales la Terriere, were released from Worcester Goal on Sunday following a hunger strike. Both women refused any information with regard to themselves, but one has been identified as Lilian Lenton, who was at liberty under Cat and Mouse Act. The second prisoner is still unidentified."

After another hunger-and-thirst strike, Lenton was released on 25th December to the care of Mrs Impey in King's Norton. Once again she escaped and evaded the police until early May 1914 when she was arrested in Birkenhead. "Miss Lilian Lenton, the well-known Suffragette, was rearrested at Birkenhead yesterday. She had been staying with friends, and was a Birkenhead detective. Miss Lenton was heavily veiled, and wore a cream jersey and large hat. She will be handed over to Scotland Yard detectives today."

Lenton was "indicted for feloniously breaking into a dwelling-house near Doncaster with intent to commit a felony and set fire to the same." One newspaper reported: "Mary Temple Beechcroft, said she was 72, and a housekeeper. In June last she was alone in the house, and heard a noise during the night. On going downstairs she saw accused and another, who had already been tried. The police arrived and fire-lighters were found on the stairs… paraffin and cotton wool were also discovered."

The Suffragette provided a detailed account of the trial. "Throughout the trial Miss Lenton, in spite of the fact that she was obviously weak and ill, kept up a continuous address to the jury, which practically drowned the hearing of the case." The prosecutor claimed that her actions could of resulted in the housekeeper. Lenton replied: "This is absolutely ridiculous, because we always look first to see if anyone is there."

Lenton was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment. "Although she had been committed for trial several times previously, this is the first time that any sentence has been passed on her. In Court, in spite of the fact that she was weak and ill owing to over four days' hunger and thirst strike, she continued, with a courage that dominated all in Court, to address the jury during the whole of the case, thus rendering the legal proceedings inaudible." Lenton told the judge: "No man who was anything, but a cad can possibly pass judgement on a woman who is charged with breaking laws she has had no hand in making."

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

In 1914 Eveline Haverfield, a member of the WSPU, founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Later she was appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps, Haverfield was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia. In August, 1916, Lilian Lenton went with Haverfield, Dr. Else Inglis, Elsie Bowerman, and Vera Holme to the Balkan Front.

Haverfield was appointed head of the transport column and in August 1916 she was dispatched to Russia. Her biographer, Elizabeth Crawford, has commented: "Haverfield sailed for Russia, in charge of the unit's transport column, which comprised seventy-five women noted for their smart uniforms and shorn locks. She herself is invariably described as being small, neat, and aristocratic, able to command devotion from her troops, although some of her peers, not so enamoured, were scathing of her ability."

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. The Manchester Guardian reported: "This doubled the electorate, giving the Parliamentary vote to about six million women and placing soldiers and sailors over 19 on the register (with a proxy vote for those on service abroad), simplifies the registration system, greatly reduces the cost of elections, and provides that they shall all take place on one day, and by a redistribution of seats tends to give a vote the same value everywhere, passed both Houses yesterday and received the Royal assent."

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918. Several of the women involved in the suffrage campaign stood for Parliament. Only one, Constance Markiewicz, standing for Sinn Fein, was elected. Lenton later recalled: "Men had a vote at 21, all men. Women only had a vote when they were 30, and then only if they were householders or the wives of male householders. Personally, I didn't vote for a very long time because I hadn't either a husband or furniture."

In 1924 Lenton was employed as a travelling organizer and speaker for the Women's Freedom League (WFL). During this period she often stayed with Alice Schofield in Middlesbrough. Both women were vegetarians and worked for animal welfare charities. Lenton also wrote for the WFL newsparer, The Vote and toured the country making speeches in favour of all women getting the vote. She was also editor of the WFL's The Women's Bulletin for eleven years.

In July 1925, Lenton spoke at a meeting in Clyde. "Many of the questions the speaker (Lilian Lenton) is asked: several are irrelevant, many simply argumentative, whilst others show a real desire for information and understanding. We have the young men who fear the competition of women in the labour market, alleging that because of it they are unemployed – on what the woman is to live they neither know nor care; and others openly evince apprehension lest, when a woman can earn a decent living, her desire for the ties of matrimony may diminish, and loudly answer in the affirmative when asked if they like the idea that a woman is dependent upon them. Not few in number are the youths of about 16 who assert our "mental and physical" inferiority to the male sex."

After 1925 she was financial secretary of the National Union of Women Teachers. She was a member of the Status of Women Committee and the honorary treasurer of the Suffragette Fellowship. She also gave several interviews on her time in the Women's Social and Political Union. This included two on the BBC: Charlotte March and Lilian Lenton: Militant Suffragettes and Lilian Lenton explains the Cat and Mouse Act

Lilian Lenton died in Twickenham on 28th October 1972.

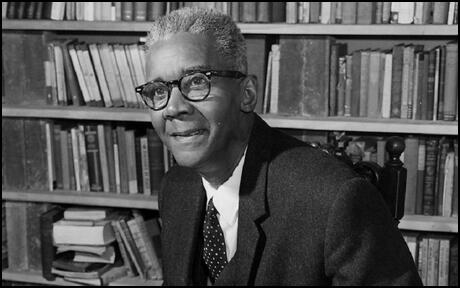

On this day in 1901 C. L. R. James, the son of a schoolteacher, was born in Tunapuna, Trinidad, on 4th January, 1901. He was deeply influenced by his mother who was a avid reader. A very intelligent child, at the age of six he won won a scholarship to Queens Royal College. As a young man James met George Padmore and the two men became close friends.

After leaving college James worked as a school teacher and as a cricket reporter. He also wrote two novels, La Divina Pastora (1927) and Triumph (1929). He took a keen interest in politics and wrote a biography of the Trinidadian labour leader, Arthur Cipriani. The book, Life of Captain Cipriani was published in 1929.

The cricketer, Learie Constantine, suggested that James should emigrate to England. He arrived in 1932 and for a while lived with Constantine in Nelson, Lancashire. He also managed to get work reporting cricket matches for the Manchester Guardian. James was a strong supporter of West Indian independence. A pamphlet that he wrote, The Case for West Indian Self-Government, was published in 1933 by Leonard Woolf.

C. L. R. James moved to London and during this period he studied the work of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Leon Trotsky. He initially joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and after moving to London became chairman of its Finchley branch. He also wrote for left-wing journals such as the New Leader and Controversy. James became a Marxist and left the ILP to form the Revolutionary Socialist League. James, now a follower of Trotsky, was highly critical of the government of Joseph Stalin and the British Communist Party.

In 1936 James published Minty Alley. The novel was based on his childhood in Trinidad. He also wrote a play about Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the Haitian revolution, and in 1936 Paul Robeson played the leading role at its production at the Westminster Theatre.

James also published several books on politics including Abyssinia and the Imperialists (1936), World Revolution 1917-1936 (1937). This history of the Comintern was highly critical of Stalin's 1924 pronouncement, "Socialism in One Country" and provided support for the ideas of Leon Trotsky. His study of the Haitian revolution, The Black Jacobins, was published in 1938.

James moved to the United States in October 1938. He lectured on political issues and continued to published books about politics including Dialectical Materialism and the Fate of Humanity (1947), Notes on Dialectics (1948),The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the USA (1948), State Capitalism and World Revolution (1950) and The Class Struggle (1950). James also wrote extensively about the work of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville.

The Marxist writings of James upset Joseph McCarthy and fellow right-wingers and he was eventually deported from the United States. James lived for a while in Africa but in 1958 returned to the West Indies. Influenced by the events of the Hungarian Rising in 1956, this book Facing Reality (1958) reveals a disillusionment with both Communism and Trotskyism. During this period he worked on a biography of George Padmore and parts of the book appeared in The Nation journal.

In 1963 James published Beyond a Boundary. The book is a combination of autobiography and a detailed analysis of sport and politics. Other books by James include Radical America (1970) and Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution (1977) and Radical America (1970). C. L. R. James moved back to London and died in Brixton in May, 1989.

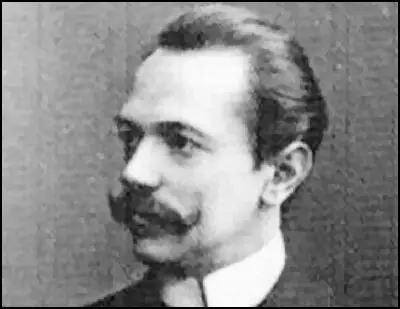

On this day in 1919, Chancellor Friedrich Ebert ordered the removal of Emil Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Emil Eichhorn was born in Chemnitz-Röhrsdorf on 9th October, 1863. He became an apprentice as a glass worker in 1878. Eichhorn became active in politics and became a member of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). He also wrote for socialist newspapers.

In April 1917 left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party formed the Independent Socialist Party. Members included Emil Eichhorn, Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Breitscheild, Julius Leber, Ernst Thälmann, Emil Eichhorn and Rudolf Hilferding.

On 9th November, 1918, he was appointed head of the Police Department. As Rosa Levine pointed out: "A member of the Independent Socialist Party and a close friend of the late August Bebel, he enjoyed great popularity among revolutionary workers of all shades for his personal integrity and genuine devotion to the working class. His position was regarded as a bulwark against counter-revolutionary conspiracy and was a thorn in the flesh of the reactionary forces."

On 4th January, 1919, Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, ordered the removal of Eichhorn, as head of the Police Department. Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "The Berlin workers greeted the news that Eichhorn had been dismissed with a huge wave of anger. They felt he was being dismissed for siding with them against the attacks of right wing officers and employers. Eichhorn responded by refusing to vacate police headquarters. He insisted that he had been appointed by the Berlin working class and could only be removed by them. He would accept a decision of the Berlin Executive of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, but no other."

Members of the Independent Socialist Party and the German Communist Party jointly called for a protest demonstration. They were joined by members of the Social Democratic Party who were outraged by the decision of their government to remove a trusted socialist. Eichhorn remained at his post under the protection of armed workers who took up quarters in the building. A leaflet was distributed which spelt out what was at stake: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers. The blow which is aimed at the Berlin police chief will affect the whole German proletariat and the revolution."

One of the organisers of the protests, Paul Levi, argued: "The members of the leadership were unanimous: a government of the proletariat would not last more than a fortnight... It was necessary to avoid all slogans that might lead to the overthrow of the government at this point. Our slogan had to be precise in the following sense: lifting of the dismissal of Eichhorn, disarming of the counter-revolutionary troops, arming of the proletariat. None of these slogans implied an overthrow of the government."

Friedrich Ebert, Germany's new chancellor, called in the German Army and the Freikorps to bring an end to the rebellion. By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Wilhelm Pieck on 16th January. Paul Frölich, the author of Rosa Luxemburg: Her Life and Work (1940) has explained what happened next: "A short while after Liebknecht had been taken away, Rosa Luxemburg was led out of the hotel by a First Lieutenant Vogel. Awaiting her before the door was Runge, who had received an order from First Lieutenants Vogel and Pflugk-Hartung to strike her to the ground. With two blows of his rifle-butt he smashed her skull. Her almost lifeless body was flung into a waiting car, and several officers jumped in. One of them struck Rosa on the head with a revolver-butt, and First Lieutenant Vogel finished her off with a shot in the head. The corpse was then driven to the Tiergarten and, on Vogel's orders, thrown from the Liechtenstein Bridge into the Landwehr Canal, where it was not washed up until 31 May 1919."

Emil Eichhorn later commented: "The Berlin proletariat was sacrificed to the carefully calculated and artfully executed provocation of the government of the day. The government sought the opportunity to deal the revolution its death blow... Although to some extent armed, the proletariat was in no way equipped for serious fighting; it fell into the trap of the pacification negotiations and allowed its strength, time and revolutionary fervour to be destroyed. In the meantime, the government, having at its disposal all the resources of the state, could prepare for its final subjugation."

After the suppression of the Spartacus Uprising, Eichhorn went into hiding. In 1920 he joined the German Communist Party but remained a supporter of the theories of Rosa Luxemburg and this brought him into conflict with Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. In 1921 Paul Levi resigned as chairman of the KPD over policy differences. Later that year, Lenin and Trotsky, demanded that he should be expelled from the party. Eichhorn resigned along with Levi. Emil Eichhorn died in Berlin on 26th July, 1925.

On this day in 1920 William Colby, the son of an army officer, was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on 4th January, 1920. He attended Princeton University graduated in 1940. In 1941 Colby joined the United States Army and in 1943 the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The OSS trained him for special missions, and he served behind enemy lines in France and on one occupation helped to destroy a German communication centre in Norway.

After the war Colby obtained a law degree from Columbia University in 1947. After working for a short time in a law firm, Colby joined the CIA. He served in Stockholm (1951-1953) and then in Rome (1953-1958), where he helped to arrange the defeat of the Communist Party in the Italian general election.

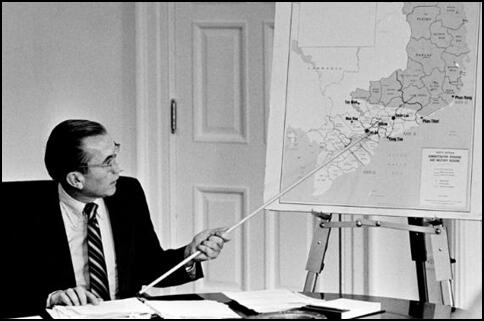

Colby was CIA station chief in Saigon from 1959 to 1962 and headed the agency's Far East division from 1962 to 1967. Then from 1968 to 1971 he directed the Phoenix program during the Vietnam War. It is estimated that as many 60,000 supporters of the National Liberation Front were killed during the Phoenix program. However, Colby put the number at 20,587. Although Colby maintained that the deaths characteristically arose in combat and not as a result of cold-blooded murder, critics of Phoenix labeled it an assassination program and a crime against humanity.

During the Watergate Scandal President Richard Nixon became concerned about the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency. Three of those involved in the burglary, E. Howard Hunt, Eugenio Martinez and James W. McCord had close links with the CIA. Nixon and his aides attempted to force the CIA director, Richard Helms, and his deputy, Vernon Walters, to pay hush-money to Hunt, who was attempting to blackmail the government. Although it seemed Walters was willing to do this, Helms refused. In February, 1973, Nixon sacked Helms. His deputy, Thomas H. Karamessines, resigned in protest.

James Schlesinger now became the new director of the CIA. Schlesinger was heard to say: “The clandestine service was Helms’s Praetorian Guard. It had too much influence in the Agency and was too powerful within the government. I am going to cut it down to size.” This he did and over the next three months over 7 per cent of CIA officers lost their jobs.

On 9th May, 1973, Schlesinger issued a directive to all CIA employees: “I have ordered all senior operating officials of this Agency to report to me immediately on any activities now going on, or might have gone on in the past, which might be considered to be outside the legislative charter of this Agency. I hereby direct every person presently employed by CIA to report to me on any such activities of which he has knowledge. I invite all ex-employees to do the same. Anyone who has such information should call my secretary and say that he wishes to talk to me about “activities outside the CIA’s charter”.

There were several employees who had been trying to complain about the illegal CIA activities for some time. As Cord Meyer pointed out, this directive “was a hunting license for the resentful subordinate to dig back into the records of the past in order to come up with evidence that might destroy the career of a superior whom he long hated.”

It has been argued by John Simkin that it was this Schlesinger directive that encouraged senior CIA operatives to leak information to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein about Nixon's attempt to cover-up the Watergate Scandal. On 16th May, 1973, Deep Throat has an important meeting with Woodward where he provides information that was to destroy Nixon. This includes the comment that the Senate Watergate Committee should consider interviewing Alexander P. Butterfield. Soon afterwards told a staff member of the committee (undoubtedly his friend, Scott Armstrong) that Butterfield should be asked to testify before Sam Ervin.

On 25th June, 1973, John Dean testified that at a meeting with Richard Nixon on 15th April, the president had remarked that he had probably been foolish to have discussed his attempts to get clemency for E. Howard Hunt with Charles Colson. Dean concluded from this that Nixon's office might be bugged. On Friday, 13th July, Butterfield appeared before the committee and was asked about if he knew whether Nixon was recording meetings he was having in the White House. Butterfield now admitted details of the tape system which monitored Nixon's conversations.

The appointment of Schlesinger as Director of the CIA created a great deal of unrest in the agency and after three months Nixon decided to replace him with Colby. When in 1975 both houses of Congress set up inquiries into the activities of the intelligence community, Colby handed over to the Senate committee chaired by Frank Church details of the CIA's recent operations against the left-leaning government in Chile. The agency's attempts to sabotage the Chilean economy had contributed to the downfall of South America's oldest democracy and to the installation of a military dictatorship.

His testimony resulted in his predecessor, Richard Helms, being indicted for perjury. Colby was attacked by right-wing figures such as Barry Goldwater for supplying this information to the Frank Church and on 30 January 1976, President Gerald Ford replaced him with George H. W. Bush.

In retirement Colby published his memoirs Honorable Men. This resulted in him being accused of making unauthorized disclosures, and was forced to pay a $10,000 fine in an out-of-court settlement.

On 28th April 1996 William Colby went on a canoe trip at Rock Point, Maryland. His body was found several days later. Later police claimed that there was no evidence of foul play.

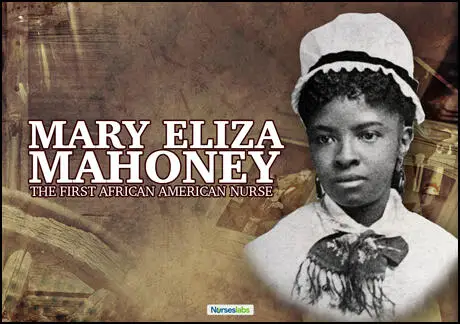

On this day in 1926 Mary Mahoney died. Mahoney was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts on 7th May, 1845. At eighteen Mahoney found work at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. For the next fifteen years she was employed as a cook and cleaner and it was not until 1878 that she was accepted as a student nurse. Training was rigorous and of the forty-two students accepted in 1878, only four, including Mahoney, graduated.

Mahoney developed a reputation as an outstanding nurse and was asked to look after private patients in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington and North Carolina. Her successful career played an important role in overcoming the considerable racial prejudice against African American nurses that existed at this time.

Mahoney became one of the first African-American women to join the American Nurses Association. In an attempt to combat racial discrimination in nursing, Mahoney joined with Martha Franklin and Adah Thoms to establish the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). A deeply religious woman, Mahoney became the NACGN national chaplain.

In 1911 Mahoney moved to New York where she took charge of the Howard Orphan Asylum for Black Children in Kings Park, Long Island.

Mary Mahoney was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and in 1921, aged seventy-six, was one of the first women in Boston to register to vote after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Mary Mahoney died of breast cancer on 4th January, 1926, and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts.

On this day in 1932 Clint Hill. He attended Concordia College, Minnesota, where he studied history. After graduating in 1954 he joined the US Army. He left in 1957 and found work with the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad.

Hill entered the Secret Service in September 1958. Hill did investigative and protection work in Denver until 1959 when he was assigned to the staff of the White House where he helped to protect Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy.

In November 1963 Hill went on the presidential trip to Texas. His special duty was to protect Jackie Kennedy. On the motorcade tour of Dallas on 22nd November, 1963, Hill rode on the running board of the Secret Service car immediately behind the presidential car. After the first shot was fired Hill ran forward: "I jumped onto the left rear step of the Presidential automobile. Mrs. Kennedy shouted, "They've shot his head off," then turned and raised out of her seat as if she were reaching to her right rear toward the back of the car for something that had blown out. I forced her back into her seat and placed my body above President and Mrs. Kennedy."

At the Warren Commission Hill claimed he only heard two shots. He also thought the second shot sounded very different from the first shot. Some researchers have claimed that this indicated that it had been fired from a different gun. Another explanation is that the second and third shots were fired at virtually the same time.

Hill was praised for his bravery. He was the only Secret Service agent who attempted to cover the president's body with his own. Rufus Youngblood had done the same thing to protect Lyndon B. Johnson in his car.

On this day 1943 Caroline O'Day, died. She was born in Perry, Houston County, on 22nd June, 1875. After graduating from the Lucy Cobb Institute she studied art in France (Paris) and Germany (Munich).

A member of the Democratic Party, O'Day was commissioner of the New York State board of social welfare (1923-1934). She was elected to Congress in November, 1934, and over the next few years she played a leading role in the campaign to free Tom Mooney and Warren Billings. O'Day, who served in Congress until January, 1943.

On this day in 1965 Georgette Meyer (Dickey Chapelle), becomes the first American journalist to die in Vietnam. Georgette Louise Meyer was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on 14th March 1919. After leaving Shorewood High School she briefly attended aeronautical design classes at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. According to her biographer: "She returned home a few months later, knowing she would rather fly a plane than design one and began working at a Milwaukee airfield. When Chapelle's mother learned of her affair with a pilot, she was sent to live with her grandparents in Florida."

After working in a series of jobs in Florida, she found employment with Trans World Airlines in New York City. She attended photography evening classes run by Tony Chapelle. She eventually married Chapelle. This ended in divorce but she adopted the professional name Dickey Chapelle. She took the name "Dickey" from her favourite explorer, Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

During the Second World War she become a war correspondent photojournalist for National Geographic. In 1942 she spent time with the Marines who were on training courses in Panama. This included covering the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa with the Marines. Roberta Ostroff, the author of Fire in the Wind: The Biography of Dickey Chappelle (1992) has argued that she "was a tiny woman known for her refusal to kowtow to authority and her signature uniform: fatigues, an Australian bush hat, dramatic Harlequin glasses, and pearl earrings."

After the war, Dickey Chapelle covered all the major wars and rebellions. This included the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, where she was captured and jailed for seven weeks. This was followed by spells in Algeria and Lebanon. She later wrote in What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself (1962): "I had become an interpreter of violence. I'd covered three revolutions in three years - Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon.... I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world."