Warren Billings

Warren Billings, the son of a carpenter, was born at Middletown in 1893. His father died two years later leaving his mother a widow with nine children.

Billings did a variety of jobs including farm labourer, a shoe lining cutter and a streetcar conductor. He moved to San Francisco in 1913 and soon afterwards he became active in radical politics.

Billings joined the Socialist Party of America where he met Tom Mooney. The two men became involved in a strike in a shoe factory. During the dispute Billings was arrested for assault with a deadly weapon.

On his release in 1914 he went to live with Mooney and his wife, Rena Mooney. Blacklisted in the shoe manufacturing trade, Billings managed to find work in the Ford assembly plant in San Francisco.

In 1916 Billings and Mooney became involved in a strike of streetcar workers employed by the United Railroads (URR). On 11th June a high-voltage tower of the Sierra and San Francisco Power Company, which served the URR, was dynamited in the San Bruno hills. Soon afterwards the URR offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters.

Martin Swanson, who worked for the Public Utilities Protective Bureau, became convinced that Tom Mooney was the man responsible for the bombing. On 13th June 1916 Swanson interviewed Israel Weinberg, a jitney bus driver who had often taken Mooney to trade union meetings. Swanson offered Weinberg a share of the $5,000 reward if he could provide evidence that would convict Mooney of the San Bruno bombing.

Soon afterwards Swanson approached Billings. As well as a share of the $5,000 reward Billings was offered a job with the Pacific Gas and Electric Company if he could provide information connecting Mooney with the San Bruno bombing. Billings refused and reported the approach to Mooney and George Speed, the secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

On 22nd July, 1916, employers in San Francisco organized a march through the streets in favour of an improvement in national defence. Critics of the march such as William Jennings Bryan, claimed that the Preparedness March was being organized by financiers and factory owners who would benefit from increased spending on munitions.

During the march a bomb went off in Steuart Street killing six people (four more died later) and 40 were badly wounded. Two witnesses described two dark-skinned men, probably Mexicans, carrying a heavy suitcase near to where the bomb exploded.

The Chamber of Commerce immediately offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the dynamiters. Other organizations and individuals added to this sum and the reward soon reached $17,000. Offering such a large reward was condemned by the editor of the New York Times claiming it was a "sweepstake for perjurers".

On the evening of the bombing Martin Swanson went to see the District Attorney, Charles Fickert. Swanson told Fickert that despite the claims that it was the work of Mexicans, he was convinced that Billings and Tom Mooney were responsible for the explosion. The next day Swanson resigned from the Public Utilities Protective Bureau and began working for the District Attorney's office. On 26th July 1916, Fickert ordered the arrest of Billings, Mooney, his wife Rena Mooney, Israel Weinberg and Edward Nolan.

None of the witnesses of the bombing identified the defendants in the lineup. The prosecution case was instead based on the testimony of two men, an unemployed waiter, John McDonald and Frank Oxman, a cattleman from Oregon. They claimed that they saw Billings plant the bomb at 1.50 p.m. Oxman also said he saw Tom Mooney and his wife talking with Billings a few minutes later. However, at the trial, a photograph showed that the couple were over a mile from the scene. A clock in the photograph clearly read 1.58 p.m. The heavy traffic at the time meant that it was impossible for Mooney and his wife to have been at the scene of the bombing at 1.50 p.m. Despite this, Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life-imprisonment. Rena Mooney and Israel Weinberg were found not guilty and Edward Nolan was never brought to trial.

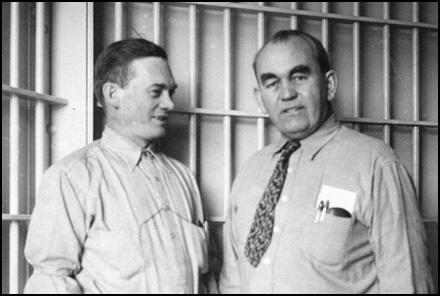

Billings was sent to Folsom Prison. For several years he worked in the stone quarry. He also taught himself the skills of a watch repairman and eventually became the official prison watchmaker.

A large number of people believed that Billings and Mooney had been framed. Those involved in the campaign to get them released included Robert Minor, Fremont Older, George Bernard Shaw, Heywood Broun, Samuel Gompers, Eugene V. Debs, Roger Baldwin, John Dewey, John Haynes Holmes, Oswald Garrison Villard, Norman Hapgood, Crystal Eastman, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Lincoln Steffens, H. L. Mencken, Burton K. Wheeler, Sherwood Anderson, Abraham Muste, Harry Bridges, James Larkin, James Cannon, William Z. Foster, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, William Haywood, William A. White, Carl Sandburg, Arturo Giovannitti and Robert Lovett.

The American government also became concerned about the Mooney and Billings Case and the Secretary of Labor, William Bauchop Wilson, delegated John Densmore, the Director of General Employment, to investigate the case. By secretly installing a dictaphone in the private office of the District Attorney he was able to discover that Mooney and Billings had probably been framed by Charles Fickert. The report was leaked to Fremont Older who published it in the San Francisco Call on 23rd November 1917.

There were protests all over the world and President Woodrow Wilson called on William Stephens, the Governor of California, to look again at the case. Two weeks before Tom Mooney was scheduled to hang, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment in San Quentin. Soon afterwards Mooney wrote to Stephens: "I prefer a glorious death at the hands of my traducers, you included, to a living grave."

In November 1920, Draper Hand of the San Francisco Police Department, went to Mayor James Rolph and admitted that he had helped Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson to frame Mooney. Later two witnesses, Edgar Rigall and Earl K. Hatcher, came forward and provided evidence that Frank Oxman was 200 miles away during the bombing and could not have seen what he told the court at the trial of Mooney. In February 1921 John McDonald confessed that the police had forced him to lie about the planting of the bomb. Despite this new evidence the Californian authorities refused a retrial.

After the publication of this new evidence it was generally believed that Charles Fickert and Martin Swanson had framed Mooney and Billings. However, Republican governors over the next twenty years: William Stephens (1917-1923), Friend Richardson (1923-1927), Clement Young (1927-1931), James Rolph (1931-1934) and Frank Merriam (1934-39) all refused to order the release of the two men.

In 1937 a group of politicians led by Caroline O'Day, Nan Honeyman, Jerry O'Connell, Emanuel Celler, James E. Murray, Vito Marcantonio, Gerald Nye and Usher Burdick asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to intercede in the case. When Roosevelt declined Murray and O'Connell introduced a resolution in the Senate calling on Governor Frank Merriam to pardon Mooney and Billings.

In November 1938 Culbert Olson was elected as Governor of California. He was the first member of the Democratic Party to hold this office for forty-four years. Soon after gaining power Olson ordered that Mooney and Billings should be released from prison.

Billings opened a small jeweler's shop in San Francisco after leaving Folsom Prison. He got married and eventually became vice president of the Watchmakers Union.

Warren Billings, who was officially pardoned in December 1961 for the San Francisco bombing, died in 1972.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Fickert, during the trial of Warren Billings (September 1916)

Gentlemen, the case here is by far more serious than any other case that was ever submitted to any jury. It is not a question of this defendant against Mrs. Van Loo; that unhappy woman is at rest; those orphan children must go through life, thinking of the scenes that were enacted there. But here, gentlemen, was the offense: This American flag—this American flag was what they desired to offend. They offended that by killing the women and men that worshipped it. Here is another photograph of Mrs. Van Loo, dying on the streets of our city, and in a feeble hand she holds the American flag, and if that flag is to continue to wave, you men must put an end to such acts as these. So far as I am concerned, no personal consequences are going to swerve me one jot from my sworn duty. What are personal consequences, what are political consequences in a crisis like this? Gentlemen, the very life of the Nation is at stake. No foreign foes were on our land at this time, but some traitor, some murderous villain, who, with his associates, perpetrated this crime, and to disgrace the flag, they took the life of this unfortunate woman.

Now, we have here, gentlemen, enough evidence at 721 Market Street - and God only knows, if it had not been for the action of Estelle Smith, and those who saw him there. God only knows, there may have been three or four hundred children of the working class of San Francisco blown into eternity.

He (Billings) probably delighted in hearing the cries of these women and children. My God! You have heard it described here, and I have seen it afterwards - women with babes in their arms, their legs shot away, crawling away from the wreck of the cruel shell, and if you could have heard the cries of some of those children, if you could have seen, like I have seen, my friend Lawlor there blown beyond recognition, you could not have thought lightly of it.

(2) Maxwell McNutt, defending Warren Billings at his trial (September 1916)

This historic case was spawned in the brain of a private detective named Martin Swanson, and hatched in the super-heated perfervid imaginations of the Smiths, the Kidwells, the Moores and the McDonalds, and fostered and brought into being and reared by the Fickerts, the Brennans, and the Traffic Squad.

Every bit of evidence, with the exception of those four men that were on the roof of the Eiler's Building, every bit of evidence that has been produced before this jury, had been volunteered at some time or another to the Prosecution, and had been put in the ashcan. Why? Because it did not fit the "dream" of McDonald.

(3) The Secretary of Labor, William Bauchop Wilson, delegated John Densmore, the Director of General Employment, to investigate the Mooney and Billings Case. By secretly installing a Dictaphone in the office of the District Attorney he was able to discover that the men had probably been framed by Charles Fickert. Densmore's report on the case was passed to the Secretary of Labor in November 1917.

As one reads the testimony and studies the way in which the cases were conducted one is apt to wonder at many things - at the apparent failure of the district attorney's office to conduct a real investigation at the scene of the crime; at the easy adaptability of some of the star witnesses; at the irregular methods pursued by the prosecution in identifying the various defendants; at the sorry type of men and women brought forward to prove essential matters of fact in a case of the gravest importance; at the seeming inefficacy of even a well-established alibi; at the sangfroid with which the prosecution occasionally discarded an untenable theory to adopt another not quite so preposterous; at the refusal of the public prosecutor to call as witnesses people who actually saw the falling of the bomb; in short, at the general flimsiness and improbability of the testimony adduced, together with a total absence of anything that looks like a genuine effort

to arrive at the facts in the case.

These things, as one reads and studies the complete record, are calculated to cause in the minds of even the most blase a decided mental rebellion. The plain truth is, there is nothing about the cases to produce a feeling of confidence that the dignity and majesty of the law have been upheld. There is nowhere anything even remotely resembling consistency, the effect being that of patchwork, of incongruous makeshift, of clumsy and often desperate expediency.

It is not the purpose of this report to enter into a detailed analysis of the evidence presented in these cases - evidence which, in its general outlines at least, is already familiar to you in your capacity as president, ex officio, of the Mediation Commission. It will be enough to remind you that Billings was tried first; that in September 1916, he was found guilty, owing largely to the testimony of Estelle Smith, John McDonald, Mellie and Sadie Edeau, and Louis Rominger, all of whom have long since been thoroughly discredited; that when Mooney was placed on trial, in January of the year following, the prosecution decided, for reasons which were obvious, not to use Rominger or Estelle Smith, but to add to the list of witnesses a certain Frank C. Oxman, whose testimony, corroborative of the testimony of the two Edeau women, formed the strongest link in the chain of evidence against the defendant; that on the strength of this testimony Mooney was found guilty; that on February 24, 1917, he was sentenced to death; and that subsequently, to wit, in April of the same year, it was demonstrated beyond the shadow of a doubt that Oxman, the prosecution's star witness, had attempted to suborn perjury and had thus in effect destroyed his own credibility.

The exposure of Oxman's perfidy, involving as it did the district attorney's office, seemed at first to promise that Mooney would be granted a new trial. The district attorney himself, Mr. Charles M. Fickert, when confronted with the facts, acknowledged in the presence of reputable witnesses that he would agree to a new trial. His principal assistant, Mr. Edward A. Cunha, made a virtual confession of guilty knowledge of the facts relating to Oxman, and promised, in a spirit of contrition, to see that justice should be done the man who had been convicted through Oxman's testimony. The trial judge, Franklin A. Griffin, one of the first to recognize the terrible significance of the expose, and keenly jealous of his own honor, lost no time in officially suggesting the propriety of a new trial. The attorney general of the state, Hon. Ulysses S. Webb, urged similar action in a request filed with the Supreme Court of California.

Matters thus seemed in a fair way to be rectified, when two things occurred to upset the hopes of the defense. The first was a sudden change of front on the part of Fickert, who now denied that he had ever agreed to a new trial, and whose efforts henceforth were devoted to a clumsy attempt to whitewash Oxman and justify his own motives and conduct throughout. The second was a decision of the Supreme Court to the effect that it could not go outside the record in the case - in other words, that judgment could not be set aside merely for the reason that it was predicated upon perjured testimony.

There are excellent grounds for believing that Fickert's sudden change of attitude was prompted by emissaries from some of the local corporate interests most bitterly opposed to union labor. It was charged by the Mooney defendants, with considerable plausibility, that Fickert was the creature and tool of these powerful interests, chief among which are the Chamber of Commerce and the principal public-service utilities of the city of San Francisco. In this connection it is of the utmost significance that Fickert should have entrusted the major portion of the investigating work necessary in these cases to Martin Swanson, a corporation detective, who for some time prior to the bomb explosion had been vainly attempting to connect these same defendants with other crimes of violence.

Since the Oxman exposure, the district attorney's case has melted steadily away until there is little left but an unsavory record of manipulation and perjury, further revelations having impeached the credibility of practically all the principal witnesses for the prosecution. And if any additional confirmation were needed of the inherent weakness of the cases against these codefendants, the acquittal of Mrs. Mooney on July 26, 1917, and of Israel Weinberg on the 27th of the following October would seem to supply it.

These acquittals were followed by the investigation of the Mediation Commission and its report to the President under date of January 16, 1918. The Commission's report, while disregarding entirely the question of the guilt or innocence of the accused, nevertheless found in the attendant circumstances sufficient grounds for uneasiness and doubt as to whether the two men convicted had received fair and impartial trials.

Ordinarily the relentless persecution of four or five defendants, even though it resulted in unmerited punishment for them all, would conceivably have but a local effect, which would soon be obliterated and forgotten. But in the Mooney case, which is nothing but a phase of the old war between capital and organized labor, a miscarriage of justice would inflame the passions of laboring men everywhere and add to a conviction, already too widespread, that workingmen can expect no justice from an orderly appeal to the established courts.

Yet this miscarriage of justice is in process of rapid consummation. One man is about to be hanged; another is in prison for life; the remaining defendants are still in peril of their liberty or lives, one or the other of which they will surely lose if some check is not given to the activities of this most amazing of district attorneys.

(4) Eugene Debs, speech in Canton, Ohio (16th June 1918)

They would have you believe that the Socialist Party consists in the main of disloyalists and traitors. It is true in a sense not at all to their discredit. We frankly admit that we are disloyalists and traitors to the real traitors of this nation; to the gang that on the Pacific coast are trying to hang Tom Mooney and Warren Billings in spite of their well-known innocence and the protest of practically the whole civilized world.

I know Tom Mooney intimately - as if he were my own brother. He is an absolutely honest man. He had no more to do with the crime with which he was charged and for which he was convicted than I had. And if he ought to go to the gallows, so ought I. If he is guilty every man who belongs to a labor organization or to the Socialist Party is likewise guilty.

What is Tom Mooney guilty of? I will tell you. I am familiar with his record. For years he has been fighting bravely and without compromise the battles of the working class out on the Pacific coast. He refused to be bribed and he could not be browbeaten. In spite of all attempts to intimidate him he continued loyally in the service of the organized workers, and for this he became a marked man. The henchmen of the powerful and corrupt corporations, concluding finally that he could not be bought or bribed or bullied, decided he must therefore be murdered.

(5) Warren Billings, letter to a friend in Berkeley (1930)

In "doing time" the true philosopher takes the wholly reasonable view of the matter that instead of "doing time" he is merely living here - just as a settler on his frontier ranch lived for years in one little community among the same friends and relatives, making the best of conditions as he found them - doing whatever work became necessary and getting what enjoyment he could out of his meagre existence. In tact in the final analysis my prison is no different than your own - a little more restricted perhaps. Mentally there are no restrictions - we set our own horizons.

(6) Richard H. Frost, The Mooney Case (1968)

The Mooney case festered unresolved for more than twenty years, its causes widespread, its consequences pernicious. The trials and imprisonment of Mooney and Billings revealed dramatically the intolerance and injustice accorded radical dissenters before, during, and long after the First World War. The case, developing out of class social tensions and public anxieties accompanying the Preparedness Day crime, was forged through the repeated abuse of fair procedures by local law enforcement officials.