Andrew St George

Andrew St. George was born in Hungary. It is claimed that he was related to the Hungarian royal family. During the Second World War St. George worked for Army Intelligence. This included helping Raoul Wallenberg and the resistance to Nazi Germany.

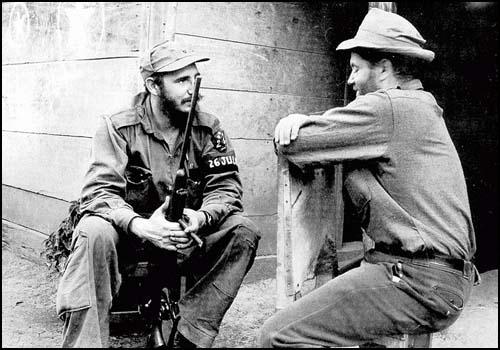

After the war St. George worked as a freelance journalist and photographer. In 1958 he went to Cuba where he met Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra. Castro asked St. George if he could arrange a meeting with Central Intelligence Agency agents. He went to Havana but the idea of the CIA having a meeting with Castro was vetoed by Washington.

St. George wrote and article on Castro's desire to talk to the American authorities. The article appeared on the front-page of the New York Times on 11th December, 1958. Unfortunately, the newspaper was on strike that day and was therefore not seen by the public.

St. George was in Havana when Fidel Castro rebels took power. José Castaño Quevedo, a Cuban who worked with the CIA in Havana, was arrested and after being tried by a revolutionary court, was sentenced to death. Jim Noel, the CIA station chief, asked St. George to see if he could get Quevedo's release. He had a meeting with Che Guevara but he refused to save Quevedo and he was executed as an "American agent".

Over the next couple of years St. George associated with anti-Castro Cubans and reported their activities for Life Magazine. Based in Miami, he accompanied members of Alpha 66 on CIA backed attacks on Cuba. On another occasion he was with Tony Cuesta and a squad of Commandos L when they sunk the Russian freighter Baku.

Later, St. George admitted he was paid $50,000 in expenses by Henry Luce as his main contact with anti-Castro exile groups. Some of this money was used to fund raids on Cuba. This included paying money to people like Gerry P. Hemming and Eddie Bayo. St. George also admitted being in contact with Roland Masferrer and Mitchell WerBell.

During this period St. George was denounced as a CIA agent. According to the authors, Warren Hinckle and William Turner (Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of JFK): "St. George's not infrequent rubbing of elbows with intelligence types led New Left conspiracy theorists to conclude that he worked for the CIA... The beleaguered St. George has spent so much time denying that he is a CIA agent that, naturally, a lot of people believe he is. Even his wife of some twenty years, Jean, sometimes thinks so... One day when St. George was suffering all the agonies of Christ because of acutely painful hemorrhoids, his wife suggested that he "go to Walter Reed (the government hospital). 'Those people in Washington must have some sort of medical plan for guys like you,' she said." (page 59)

It appears that Che Guevara was convinced that St. George was an CIA agent. In 1963 Guevara was interviewed by Rene Burri of Look Magazine when he declared that if he ever caught up with him he would "cut his throat".

In 1966 St. George was involved with Tom Dunkin in reporting the effort to depose the Francois Duvalier regime in Haiti. St. George and Dunkin also joined the team that established a base in Haiti with the long-term objective of overthrowing the Fidel Castro government in Cuba.

It has been claimed by Warren Hinckle and William Turner that in 1968 he was in "Bolivia, acting as a middleman in the frantic media negotiations hosted by greedy Bolivian generals attempting to sell for profit the Bolivian diary of St. George's one-time friend Che Guevara, whom the generals with a little help from the CIA, had captured and executed in the Andes foothills."

St. George also interviewed Frank Sturgis and Eugenio Martinez about Watergate. An article eventually appeared in Harper's Magazine. St. George claimed that E. Howard Hunt was a double-agent working inside the Richard Nixon administration. St. George implied that Watergate was the consequence of a conflict between Nixon and the CIA.

St. George continued to work as an investigative reporter. Using the name, Martin Mann, he worked for many years for the Spotlight Magazine in Washington. This included investigations of the business dealings of George W. Bush and Richard Cheney

He also published a series of reports claiming that $21.5 trillion of illicit money made off of drugs and arms smuggling to be sanitized through “reputable” banks in countries with loose banking regulations such as Israel, Belize and the Cayman Islands. He also accused the Chase Manhattan Bank, Citibank and the Bank of New York of laundering dirty money.

Andrew St. George died on 2nd May 2001.

Primary Sources

(1) Andrew St George, The Attempt to Assassinate Castro, Parade Magazine (12th April, 1964)

This week will mark the anniversary of the ill-fated disaster at the Bay of Pigs. It is exactly three years since Fidel Castro's regime threw back an exile-manned, U.S.-supported attempt to invade Cuba.

The story of that debacle has been repeatedly discussed since. It has been the subject of Congressional and executive investigations and of partisan political recrimination.

Yet one of the most important details of that Cuban defeat has not previously been revealed. It is an event that may have been the whole key to the Bay of Pigs tragedy, and its occurrence - or failure to occur - had a profound effect on the invasion itself and on subsequent history. And although it has not publicly been acknowledged, long and painstaking investigation by this reporter has documented this event.

Carried out on the highest levels of Cuba's revolutionary government, it was an attempt to assassinate Fidel Castro. And it came within a cat's whisker of success.

This plot, of course, was not the first against Castro's life, nor has it been the last. One of the records of which the bearded revolutionary leader is least proud is the number of times he has been the target of nearly successful assassination attempts.

Before detailing the most important plot, let's look at a few others. The most recent try came just before the celebrations in Havana last January commemorating the victory over Batista. U.S. security boats intercepted two speedboats crammed with anti-Castro conspirators and hundreds of petacas, plastic bombs to blast Castro from his reviewing stand.

The US government, worried about the Caribbean aftermath of a successful assassination, is not happy about such attempts. But American nervousness has not been able to do too much about it. Some of the attempts have come so close to success that Castro has been left with the apprehensive wariness of a lone fox in a hunting preserve.

An early try at an ambush was engineered by the sinister Col. Johnny Abbes, formerly intelligence chief of the Dominican Republic. Abbes, working on orders of Dominican strongman Rafael Trujillo - himself the victim of assassination - hired a swashbuckling American adventurer, Alex Rorke, son-in-law of New York's famed restauranteur, Sherman Billingsley, to pilot a speedboat that landed eight men before dawn in eastern Cuba. The plan was to ambush Castro on his way to speak at a service at the Santiago cemetery.

Through a pouring rain, Trujillo's Tommy gun team spotted Castro's chief bodyguard, Capt. Alfredo Gamonal, in the second jeep of a caravan. The killers assumed Castro was in the back seat, and their bullets chewed up Gamonal, the superintendent of cemeteries and the jeep driver. Castro, riding in the next-to-the-last jeep, was unhurt.

"He may have nine lives," Abess told Rorke, who returned to Ciudad Trujillo complaining of Castro's charmed life. "But if so, I'll try a tenth time."

Abbes acquired an apartment in Havana overlooking the CMQ television studios, where Castro appeared frequently to deliver his nationwide harangues. Another American adventurer, a one-time top competition sharpshooter, was retained by Trujillo on a down payment of $25,000 and the promise of a cool million if he managed to score a clean hit on his moving target.

The marksman said he could do it, but demanded a special weapon-a bench-adjusted telescopic carbine with a nondeflecting muzzle silencer.

"Dominican ordnance experts immediately went to work to produce the rifle," former Dominican State Security Minister General Arturo Espaillat recalls. "The weapon was completed and en route to Cuba when Trujillo canceled the project... He was afraid of Washington's fury. I really think that Fidel would be dead today if the plot had not been called off."

Prior to that attempt, another American, Alan Robert Nye, a 31-year-old Chicagoan, was convicted in Havana for conspiring to kill Castro. Fee: $100,000. Although a Cuban court had signed, sealed and delivered the order for his execution, Nye was allowed to leave the country for the US

There have been far too many of these attempts to detail here; although men like Alex Rorke, and Paul Hughes, a former American Navy jet pilot, have lost their lives because of them, Castro cannot rest easy.

Before embarking on an airplane trip, he usually inspects the plane from tip to tail. During the warm-up, he once spotted flames belching from the engine exhaust. Castro ordered the ignition cut and both pilots back into the cabin, where they explained for a half-hour that burning exhaust was normal and that it did not prove the plane booby-trapped.

During his visit to New York to attend the United Nations in 1960, Castro's food problems were magnified by his methods of selecting restaurants. A brace of bodyguards was ordered to go out and buy food from a restaurant - but never from the hotel kitchen or from the restaurant nearest the hotel. On each occasion, Castro would call out a number, say, "Three!" or "Five!" which meant they had to count off three or five restaurants before they could enter the next one, thus having presumably eluded the potential poisoners.

His security chief also carried sensitive white mice "to detect assassination attempts by radiation or nerve gas," chief body guard Gamonal explained.

But the only security measure Castro really has faith in is the one he learned in his two years of guerrilla warfare: never let anyone know where you'll show up next. In the Sierra Maestra, when Castro and his little band were making their revolution against Batista, no one but Fidel knew exactly where the day's march route would end.

The habit persists. When he made his first visit to Moscow, he left Havana and returned to it as secretly as an enemy infiltrator. No one in Cuba knew when to expect the Premier home. When his Russian airliner finally landed, there was nobody to welcome him except some startled airplane mechanics. Grinning, Castro borrowed a coin, dropped it into the nearest pay phone to let Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticos know he was back.

But is was the assassination attempt just before the Bay of Pigs that was the most significant of all. It involved several senior commanders of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces as well as key civilian leaders.

The Central Intelligence Agency, which had received absolutely reliable reports that a conspiracy to assassinate Castro was developing among his top lieutenants, decided to contact the plotters, because the US was already training its own anti-Castro force in Guatemala. CIA agents discovered the conspiracy had a wealthy contact man in Miami, a former sugar cane grower, Alberto Fernandez.

With CIA's tacit approval, Fernandez bought a converted subchaser, the Texana III, and had it outfitted with concealed deck armaments, 50-cal. machine guns, two 57 mm. recoilless rifles and a pair of small speedboats with muffled interceptor engines.

Now began one of the most daring and extraordinary secret intelligence operations ever attempted. Shuttling in the dark of night between Marathon Key and the north coast of Cuba, the Texana III was the link between the Cuban conspirators and the US

Its two deck boats skimmered up to shore less than a dozen miles from Havana to pick up their unusual passengers: Cuban rebel comandantes in full uniform and governmental functionaries carrying brief cases.

Before the sun came up, the travelers were in US waters, where they held quick conferences with American agents, sped back to Cuba the next night.

The tricky and hazardous process went on for a couple of months, and the US learned more and more about the murder conspiracy beaded by cool, brainy Comandante Humberto Sori Marin, a hero of the Castro revolution. Other top-level men involved astounded the Americans: Secret Police Chief Aldo Vera; Comandante Julio Rodriguez, deputy commandant of the San Antonio de los Banos air base; several Navy flag officers; the military superintendent of Camagüey Province; the president of the Cuban Sugar Institute; and the undersecretary of finance. They were determined to act early in 1961. The plot was to kill both Castros and touch off a general uprising.

Convinced that, regardless of what the US did, the conspirators meant business, the CIA decided to capitalize on the plot without actually participating in it. Officials readied the landing forces to go ashore at the same time. Agents began a series of secret meetings in Havana with the conspirators to coordinate their plans.

Then, just before the target date, there occurred one of those impossible mistakes nobody ever believes. A crucially important secret conference was being held with most of the top conspirators. They met in a house of known safety in Havana's Miramar suburb on a tranquil street, Calle Once. It was a large, yellow, somnolent building, lived in and owned by a respectable retired sugar engineer and his wife.

In the front patio, the engineer played gin rummy with his wife and led by many points. In the back of the house, the plotters gathered around a heavy refectory table covered with street maps, pinpointing the massive incendiary attack against the crowded downtown district of "Old Havana," which was to touch off the uprising. The Texana III had already shipped in hundreds of petacas.

Several blocks away, a militia security patrol stopped in front of another house, then entered to search it. A nervous woman in a back room fled from a rear door with her small daughter. She ran beneath garden walls and ducked into the rear entrance of the large yellow house of the engineer, an old friend.

The street was deserted. But one militiaman watched as she ran to the yellow house. So, under the blazing sky of a spring afternoon, in Miramar, the security unit walked down the street to that yellow house, that sleepy yellow house . . . .

The pity of it was that the nervous woman who ran did not have to. The security police were on a routine search. She was suspected of nothing; if she had remained, nothing would have gone wrong.

The 11 key figures of the Sori Marin conspiracy were caught in a single sweep. The four men who had been sent in by the CIA might have gotten away; they were all Cubans and carried such perfectly forged papers that two were subsequently shot under their assumed names.

But Sori Marin had no chance whatever. As the milicianos burst into the room, his pistol leaped into his hand. But the security men's snub-nosed Czech Tommy guns chattered and Sori Martin crumpled as he tried to crash though a window.

And it was all a mistake. The militia walked in by mistake. The woman ran away by mistake.

Washington working with fragmented information, decided it was too late to halt the invasion troops staging for departure in Guatemala. There was no way to know just how badly the conspiracy had been crippled; there was a possibility that many of its members had not been identified and would thus be able to carry out the plans.

It was a forlorn hope. April 17, at dawn, the first of the invasion troops splashed through the surf onto Giron Beach. April 17, at dawn, the seven top conspirators, led by Sori Martin, wounded and supported by his guards, but still wearing his uniform, were executed in Havana. Within the next few hours they were followed to the wall by the captured CIA men. The rest, the slaughter at the Bay of Pigs, is history.

US security and intelligence agencies are now more worried about the possibility of a successful assassination. For Washington - which once gave tacit support to Sori Marin - now feels that a real explosion involving Castro could trigger the most unpredictable chain reaction of the coming year, a chain reaction that conceivably could turn into World War III.

The current approach was pointed up in a quiet sort of way the day Allen Dulles - whose own job as head of the CIA ended a short time after that ill starred invasion-appeared in public for the first time to talk about it on Meet the Press.

"Mr. Dulles," the moderator asked, "in launching the Bay of Pigs invasion, you were obviously expecting a popular uprising to support it. Yet none occurred. How could you have been so wrong?"

"A popular uprising?" Mr. Dulles puffed on his pipe. "That's a popular misconception - but no, I wouldn't say we expected a popular uprising. We were expecting something else to happen in Cuba... something that didn't materialize."

As this is written, US intelligence is still expecting it to happen, but the expectation has now turned to a nervous and gnawing worry.

(2) Andrew St George, Hit and Run to Cuba with Alpha 66, Life Magazine (16th November, 1964)

It begins in the hours after midnight on Monday morning. We sit in a skiff, pretending to fish, less than a mile off the neon-lit Gold Coast of Miami Beach, waiting and watching the garish reflections dance in the tranquil water and listening to the music from the nightclubs drifting out to us. To any casual eye - but more importantly even to a suspicious one - my two companions and I are late Sunday fishermen. Actually we are at a highly secret rendezvous, waiting for Alpha 66 speedboats to pick us up and start the long southward run to Cuba.

A little past midnight they come. Two speedboats knifing out of the darkness, then circling to make sure of us. I am half pushed, huff hauled out of the skiff into a speedboat, one of my companions into the other, and we roar away.

Not until daylight do I get a chance to examine the boat in which I am riding. She is 70 feet long and every single bit of unnecessary superstructure has been shaved off as with a razor. Two 140-hp marine engines are in the stern. Amidships is the largest obtainable gas tank, the steering wheel and, above that, a gyrocompass. Four additional barrels of gasoline are lashed to the deck, two on each side. A small segment of deck at the bow provides the only shelter on board, enough for two men lying on their backs to keep most of their bodies out of the windblown spray. The boat is not comfortable, but she is fast, maneuverable, able to navigate in shallow waters and almost invisible to endue.

The man at the steering wheel wears a rubber skin-diving suit. He is Ricardo, a tall, 35-year-old, heavy-shouldered, curly-haired Cuban who captains the lead boat and also commands the two-boat mission. Each of the boats - ours is Lola and the other is Suzy, the names deriving in both cases from the radio call signs - manned by five men one or two of whom incessantly tend the engines or the pumps.

The second-in-command is Joaquin, heavy set, balling, taciturn, his face shielded by a steelworker's hard hat. There is Policarpo a gnarled, dark little fishermen. Two others - Paco, a thin, eager student, and Universo, an even-tempered ex-rifleman of Castro's onetime rebel army - work in the stern. The men also take turns at the helm.

I can see that four of them are veterans - they have seagoing tans. But Paco, the little student, is a recruit. He is pale and about to acquire a bad burn as his first campaign injury. Yet Paco obviously doesn't care. "They were telling me that I should sign up with the U.S. Army," he says cockily, "but that's not for me. Too much waiting. The fight is for now, for today."

His face blank, Ricardo adds, "Our war goes on, no matter what the US does. Our war is a different war. Our war knows no compromise."

We plunge on southward. In the early afternoon, the second boat - a near duplicate of our own but half a fool shorter - develops engine trouble and we lake her in tow. This is worrisome, but as night falls again, the men are happy. They are going to war - their war, one which they believe they are best suited to fight.

At 11 on Tuesday morning, a long, narrow rock ledge bobs into sight over the wave crests. It is thatched with grass and stunted sand palmetos, but it looks so forlorn that I am astonished to discover it is to be our base of operations. The link key has many small, calm lagoons. Ricardo throttles down and swings the boat inshore. We anchor off the tiny beach and final our landing raft. Tierra Firme feels great after a day and a half at sea. The crew of Suzy falls to the repairing of her sick engine. Huge, rusty gasoline barrels are unearthed among the rocks and flouted out to the boars on the landing raft. Universo the imperturbable veteran, unwinds a handline and sets to fishing from a ledge.

We had eaten very little on the way down except bread, crackers, cold sausage and guava marmalade. The boats, pitching like rodeo mounts, did not help our appetites. But now we have a meal. Ricardo breaks out tins of spaghetti, beef stew and canned potatoes. While we are eating. Universo comes back, triumphantly holding aloft a string of fish, and soon there is the aroma of frying oil.

Lunch ends around three with a hilarious surprise. Universo pulls out a black homemade woman's wig front the boat locker, then a blond one, and brings them both ashore. He adjusts the block wig on his head and, with a mincing curtsy, offers the blond one to Ramon, the commandant of the second boat.

Ramon adjusts his hairpiece and wiggles. The men roar. We are suspended in happiness for an instant and then, abruptly, we are serious. The two wig-wearers mount the rocks with two other men and begin to open the weapons stores hidden there. Now I see what the wigs are for - so we will look like a fishing party to Castro's spotter planes if they catch us in the open.

One by one, all the weapons are brought down to the boats. There are two Finnish 20-mm automatic cannons, standard NATO-model automatic rifles, a couple of World War II machine pistols known as "grease guns" - much admired by the men because of their rugged construction, a couple of weatherworn Garands, .45 pistols on web belts, grenades, and olive drub tin boxes of ammo.

Joaquin goes up himself to bring down a huge object he cradles tenderly. Unwrapped, it turns out to be a fully rigged 20-pound electromagnetic demolition mine.

The two cannons are plainly the troops' sweethearts The men float them out to the boats one by one, with infinite care. The bowdeck of each boat is reinforced with planking and the cannons are hoisted atop it, where they stand on the original skis the Finns once used to prop them up for battle against the Russians. Now a reinforced steel tube is run across from the guard rails on either side. The main weight of the cannon rests on the skis but the barrel, as tall as a man, rests on the tubing. A heavy steel spring is attached to the breech and to the deck planking to help absorb the recoil.

"Improvisation criolla." Ricardo says, grinning at me, and his usually impassive face shines with pride at their "native improvisation." It is, in fact, a remarkably ingenious setup The men on Alpha first discovered, from a careful vetting of the weapons market, that these Finnish cannons can be purchased by mail- for a mere $160 apiece, including shipping. Then they worked out the way to convert them into naval guns suited for their light, bouncy craft. With an automatic cannon in its bow, each speedboat becomes a formidable threat - a gunboat in every sense but the legal one.

Are the guns shipshape? Joaquin intends to find out. He fits a magazine to the breech and the lagoon reverberates with the sharp explosions of the trusty old Finnish shells.

"The shells were made to hit Communists," chortles Ricardo. "They'll find the nearest one by themselves."

The rest of the men are cleaning rifles and pistols with loving care. But Suzy's engines still won't work and, as evening falls, Ricardo decides we will stay at the base overnight, fix Suzy's entrails and then launch our operation tomorrow night. It is warm and clear. We huddle together in the gently rolling boats and, that night, for the first time, we sleep.

At 5 p.m. on Wednesday, Ricardo spreads a blue-gray aeronautical chart across Lola's main gas tank and briefs us on our mission. The objective is a bay on the northern coast of central Cuba. The curving shoreline of the bay is dotted with a profusion of fat, inviting targets - a large sugar mill with tall molasses storage towers, nearby a military barracks, and farther west a ship channel.

But on the ocean side the bay is protected by a tangle of small and large keys. "That's just why we are attacking here," says Ricardo contentedly. "This bay is so hard to navigate, Castro expects no trouble here. There are no patrol boats, no big shore-defense emplacements. And Policarpo here has lived all his life among these keys. He's a fisherman, a wonderful guide for this zone.

"We'll slip through live keys at about 10, cross the bay very quietly and approach the sugar mill front the north. Three men will go ashore in the raft with the big electromagnetic mine, attach it to the largest molasses tower, and then start back. Just before the mine is timed to explode, we’ll open fire on the barracks at close range - with our cannon, with our rifles, with our pistols, with everything - to cover their retreat and stir up more confusion. When the men return, we'll pull back into the shipping channel and attack any ships we might find en route... It's a very beautiful mission."

We set out at dusk. The sea is calm, a gentle breeze comes from the west. Ricardo stands tall behind the wheel of his vessel. Its cannon is directed straight at Cuba some 60 miles away. The two boat captains exchange rapid conversation on the walkie-talkie that serves as our radio contact.

Joaquin ducks up from the bow with a roll of masking tape and carefully begins to cover up the small red light of the gyrocompass. Then he takes over the wheel and Ricardo breaks out the electromagnetic mine, which is wrapped in canvas. It looks like a large knapsack with two metal horns protruding front the top and eight shoe-shaped magnets down the side. Universo and little Paco are assigned to carry it ashore. One of the men from the second boat is to go along for cover. Paco's eyes arc enormous in the dark as he listens to Ricardo's careful briefing. I duck under the bow, bring out a camera and infrared light gear, and begin shooting pictures in the soft, sweet, luminescent darkness.

The rain comes about an hour later. Fat warm droplets, they are the first harbingers of disaster.

A squall rises and quickly blows up into a full, furious northeaster The waves swell until they tower a full 15 feet over us. To preserve my gear, I retreat under the bow, holding say cameras and lights to my chest. A few minutes after 11, I hear muffled shouts and crawl out of my coffin-like shelter. The flashing beacon of a lighthouse is visible through the whipping curtain of rain and spume. We are within sight of Cuba.

The men are working furiously, pumping water, grappling with bits of breakaway gear. After 15 minutes I am jolted by a blow that throws me backward into the hold. I find myself underwater. A huge wave has washed across the stern and flooded the bowl. Pulling and kicking as hard as I can, I surface from the flooded hold. There are cries of "Este se hunde [It is sinking!]" A moment later I see Universo go over the side and start swimming toward the second boat, which has turned on its spotlight. I follow him. I reach Suzy after a 400-yard swim, feel her crew pull me aboard gulping and choking. But Suzy founders, too, in less than five minutes. Now I see what has happened. In the pitch darkness our guide has missed the entrance channel through the keys and the raging sea is clubbing both our boats against a high sandbank. For the second time I throw myself overboard Three or four minutes later, I stand on Cuban soil - shipwrecked.

All around us the raging surf flings after us onto the shore our possessions – rifles, gasoline tanks, water cans, cannons and my cameras We stand numb and shivering on the beach. Then I see Ricardo's tall shape and begin to move toward him. In moments we are a group again, and then Ricardo's voice turns us back into a team: "A recoger, rapido (Collect your stuff, quick)!'

It isn't difficult. After the floatsam and jetsam of gear comes Lola herself, our poor boat, hurled ashore by the fantastic force of the water. We dive back into her and come up with odd bits and pieces - a tommy gun, a camera, a toolbox, a flash battery wish its strap torn off.

Whatever I can spot of my gear is utterly ruined - the cameras water-logged and smashed, the waterproof film containers sloshing water out of the rents where their handles had been. But the rest of the men are fishing for weapons or hunting for them along the strand, and they manage to gather a half-dozen rifles and Tommy guns. Their shouts become firmer. Unlike cameras, rifles can be put back into commission. And once you have a rifle, you have a chance.

That, obviously, is Ricardo's thinking. He raises his voice above the howling wind. "In a single file! Move away from the boats! Everyone! We must move inland and hide!"

We form up instantly. Less than 15 minutes after being shipwrecked, we are marching down the beach, the men clutching rifles and the single ammo box they've been able to salvage - marching toward the storm-whipped interior. On the luminous face of my watch, which has miraculously kept going throughout, the hands stand at seven minutes of 12.

Daylight comes wet and windy on Thursday. With it comes also the realization that we are trapped on a large Cuban coastal key. "We must find another boat," says Ricardo.

Wearing his skin diver's tunic but not the trousers, which he lost during the night, he dangles an automatic rifle from his right hand and looks as calm and purposeful as ever.

Following him silently, we begin to stalk our way through the thick mangrove swamps which ring the key. Fewer than half of us have shoes. The rest struggle along barefoot. All morning we wade hip-deep among the swampy fingers of the keys, swimming - one by one - underwater whenever the thicket becomes utterly impassable. Towards noon we emerge - dazed by exhaustion, thirst, cold, hunger - at a small clearing. A dozen bamboo shacks stand back from the water's edge. Fishermen.

But this tiny cluster of Cuban property has no boat for us. It has very little of anything at all. If Fidel Castro has ever remembered to do anything for the rural poor of Cuba, he has clearly forgotten these fishermen.

We are offered some matches, a wrinkled half-packet of black, government-rolled cigarettes, a bucket of drinking water and a few pounds of gofio - flour mixed with half-refined sugar. A quick look through the wretched huts proves that these fishing folk are indeed offering us the very best they have.

Hope itself is draining away, leaving my legs hollow. I lie down under a sea grape tree and begin chewing on a small sour-tasting berry. Ricardo hovers over me, urbane, imperturbable: "There must be a boat around here somewhere. I'll take the guide and Ramon and look down the leeward side of this godforsaken key. Wait for me here with the others until we get back."

I roll deeper under the sell grape branches I am using for cover and stare at the sky, thinking of the planes that must cone sooner or later. Probably sooner - probably very soon. Our two wrecked speedboats are out on the sand - plain to see from above, plain to see from the ocean. Once anyone in authority spots them, it will be the beginning of the end. First there will be planes. Then the helicopters will come in low, circling incessantly over us, making certain that we are pinned down wherever we may be hiding. Then the first patrol boat, and the second one in the distance - and then the first militia troops will land.

We are dispersed in a wide circle, five of us watching the water, three of us the tip of the key. This is no movie scene, no passage from Hemingway: there is no conversation. But we are all thinking the same thing - it is plain from the way the men are feverishly cleaning their weapons, disassembling them and blowing tremendous gusts down inaccessible slots and recesses to rid them of clogging sand and salt.

There has been no pledge to resist, no declaration of a fight to the death. Everyone of us knows that, if discovered, we are doomed. None of the Alpha men wants to be taken alive.

The first of the milicianos heave into sight in mid-afternoon, their ugly Russian-style helmets peering over the side of their patrol launch its they chug across the inlet and vanish around the next finger of land. If they see us, they give no sign of it. Joaquin crouches next to me, his automatic rifle in the crook of his thick arm, his face expressionless.

"Sons of whores;" he says softly. Then, after a brief silence, he whispers, "Did I ever show you a picture of my children and my wife?"

He has a stunningly lovely woman.

"She's in Guanajay. Guanajay is the woman’s prison. They gave her 20 years for conspiring against the government - just because I got away. I send her packages from Miami."

Time drags as slowly as it must for the condemned. The mosquitoes feast on us in small, blood-greedy clouds. Huge swamp crabs scurry near. Stretched on the ground, our silent, motionless bodies must look temptingly like carrion.

Universo, old reliable Universo, sees it first. "Pero que carajo, que carajo clase de bote viene por ahi…”

Then I see it too - a small, old gaff-rigged sloop - sailing toward us across the water, softly, smoothly, unforgettably beautiful. It bumps gently against the mangrove roots less than 100 feet away and Policarpo's hairy, leathery, lovely mug comes up front thee little wooden hut in the stern. Suddenly I realize that Ricardo is getting up from the bottom and stretching himself against the most with it look that is more insouciant than usual, and I hear him announce in a voice of studied calm, "Caballeros, your new boat leaves at sundown."

Our jib is in tatters. We have been at sea 17 hours tossing violently in 12- to 15-foot waves, with a howling wind that makes everything aboard scream in anguish. I have counted every hour since we left. My watch somehow ticks on.

Our boat, our purloined lady, is an ancient craft about 24 feel long. We talk about her. We wonder about her history as we flee. She has broad gunwales and a deep, open hold. Policarpo thinks she was built half a century ago to ferry sacks of sugar and rice among the keys or down the coastline of northern Cuba. Her rudder is it roughhewn wooden tiller mounted on a fall rear deck, which also mounts a tiny wooden hut that serves to shelter the helmsman. But there is shelter for no one else. The rest of us crouch wretchedly in the hold, lashed by the salt spray, flogged by the relentless wind.

The trouble is, of course, that we are sailing back again into the raw nor'easter that wrecked our speedboats yesterday. The wind shows no sign of abating and neither do the waves. Our boat mounts the swells with high-pitched groans, but she keeps on.

The seams are giving way. We are shipping a good deal of water over the sides but, even more ominously, we are shipping more and more through the bottom. To bail the boat we have two rusty, quart tin cans and a bucket. At first, Joaquin bails all by himself - with almost trancelike speed, hour after hour - but soon we are taking hourly turns.

One by one the men begin to give out, to give up. Young Paco rolls flat on his face in the bow and refuses to answer when his turn to bail is called. As midday turns into dusk, hope of finding help wanes with the waning daylight. Old Universo is next to go. He sprawls next to Paco and appeals to his long-dead mother in groans of abject agony.

Towards midnight, a third man, Julio, another old soldier from Suzy's crew, joins. them. All three shake uncontrollably with attacks of cold and fever.

We have no compass. By day we navigate by the sun and by what Ricardo calls "the color of the water," which tells the depth and direction of the various undersea channels. By night we try to follow the stars whenever we can catch a glimpse of them across the scurrying clouds.

The tiller is far from sound. A man has to stand watch with the helmsman, holding a long plank against the current to protect the rudder. Steering is made even more difficult by the fact that the jib hangs like a line of tattered distress flags.

We cannot be doing more than two knots through these wild waters. Slowly, painfully, we struggle towards the north. Only Ricardo, among all of us, seems confident and unaffected. Twice a day he passes a handful of gofia to everyone able to get up to take it. Though it is painful to swallow the dry flour with my salt-blistered mouth, I force it down. I am weary and discouraged, and sense in the wind and the sea the rising whistle of death.

Sprawled face down on the wet planks, it occurs to me that Malraux's retired old revolutionary was right after all: When you have only one life, you should not try too hard to change the world.

On Saturday the sun rises at 6:47. I note the hour and see it pass into oblivion, a number. I know that unless something happens today, we are done. No matter how fast we bail, the water in the bottom is slowly rising and our last strength is failing.

A few minutes past 7:00, I see Policairpo, smaller and more gaunt than ever, swing forward from the stern. He lowers the mainsail. A final feeling of defeat spreads through me, for I know what this means - the arthritic steering rig has finally given up the ghost.

But I am wrong. Invisible from the deck, the dark-topped crest of a tiny island is slowly floating into view from the west. It is the British Cay Sal and it is a sight to raise the dead. The sick clamber up and we all cluster in the stern. Our creaking, watersoaked old lady, her mainsail at half-mast, begins tacking toward shore. In another half hour the sun comes out and we can see the Union Jack flutter over the low, whitewashed administration building.

Ricardo sits straddling the roof of the helmsman's hut, his long, bare legs dangling happily, and he has the look of a strange creature. He shouts gleefully, "We have arrived!" Then he turns to me and, all at once serious, says, "Andrew, you're one of us. Help us get sonic new boats and we'll go back to Cuba."

(3) Adventurous aviators slip past US patrols, set out to bomb Cuba, Life Magazine (14th November, 1960)

On Halloween night, a Beechcraft Bonanza, bearing identification number 4274-D, took off near Fort Pierce, Fla. into a raging thunderstorm. Next day the aircraft was reported both stolen and missing. It has not been found.

Four days later, after a period in which he was held a voluntary prisoner, Photographer Andrew St. George was able to reveal the fantastic story behind the flight.

It was a feat of derring-do against Cuba's Fidel Castro. Had it succeeded it surely would have given Castro new fuel for his strident attacks on the US

Two men were aboard the plane, both Americans. One was a former US military flier named Paul Hughes, 32, an adventurer who has been on every side of the Cuban fence. Once he smuggled arms to Castro and he flew jets in the Castro air force. Later he fell out with the Cuban and came to hate him - he told St. George, for giving him "a fist in my face." Since then, Hughes said, he has made many sneak flights to Cuba, stealing planes and gasoline, tossing 85-cent flares in Cuban cane fields. He had been barely evading the FBI and US border patrol.

The second man was one Jay Hunter, an adventurer who hinted mysteriously at dark deeds in the Middle East and claimed to have been a US Marine demolitions expert.

St. George, himself a veteran of the Cuban campaigns, learned what was afoot when a furtive phone call summoned him to "something big" in Miami. He was conducted to a darkened house and told that he would not be permitted to leave until the projected raid was under way. Then, to his astonishment, he was shown three 100-pound practice bombs in the charge of "Bombardier" Hunter.

The bombs were painted with the names of three young Americans executed by Castro last month (LIFE Oct. 31) after an abortive invasion of Cuba. The mission, called "Trick or Treat," was aimed to hit the Havana power plant. Molotov cocktails and leaflets identifying the raiders were also to be dropped. The plotters said this was meant as revenge and they "wanted the world to know about it" once it was safely launched.

Later, under strict surveillance, St. George was driven 120 miles north to Fort Pierce where he watched Hunter pack the bomb cases with black powder, gelatin, dynamite, scrap iron and homemade shotgun shell detonators.

Finally, near the field where the Beechcraft was parked, St. George was led away. "They had wanted heavy weather to get clear of the border patrol," he reported. "It was a wild night with rain coming in sheets. I think they got more weather than they bargained for."

(4) Tom Dunkin, Deposition on Project Nassau (29th August 1969)

I first became aware that the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) was going to film a documentary of a planned invasion of the Republic of Haiti by Cuban and Haitian exiles some time around April or May, 1966. Mr. Andrew St. George, a freelance writer with whom I had been acquainted since we were reporting on the activities of Fidel Castro from the hills of Oriente Province, Cuba, in July 1958, first called this operation to my attention. At this time I was employed as a newspaper reporter for the Atlanta Journal.

During the same period (April-May, 1966), I attended a meeting at the home of one Mitchell Wer Bell in Powder Springs, Georgia, along with Andrew St. George and a Mr. Jay McMullen, who St. George introduced to me as a producer from CBS. At this meeting the discussion was very general in nature and principally concerned with the feasibility of undertaking a filmed documentary of an attempted invasion of Haiti. It was also at this time that Jay McMullen approached me with regard to my future availability for employment on this project as a cameraman and writer in the event that the operation took place. At this stage, there were no concrete plans discussed in my presence. The project seemed to be in the offing. Wer Bell was obviously being contacted because of his knowledge of and contacts in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Latin America in general.

My next direct involvement in the project took place on September the 11th, 1966. About 7:00 a.m. I received a telephone call from St. George. He asked me to meet him at the Atlanta airport. On this occasion, St. George was accompanied by Jay McMullen, a cameraman named James Wilson, and a sound technician named Robert Funk. I gathered from their conversation that they had been filming something to do with the invasion operation up in the New Jersey area. The entire crew stayed in Atlanta about two or three days.

It was on Sunday, September the 11th, 1966, that Jay McMullen offered me a job on his CBS production crew as general assistant. My duties were to do camera and sound work and anything else that came up. I was hired on a freelance basis by McMullen and he told me my salary would be $150.00 per week plus expenses for food, lodging and transportation. McMullen did not have to do a selling job on me, I was eager to become a part of what then had all the earmarks of being a top news project.

On September 12, 1966, I took a two-months' leave of absence from the Atlanta Journal. My agreements with Jay McMullen were all oral, there was no written contract of employment made.

On Monday and Tuesday, September 12-13, 1966, accompanied by the above named CBS crew members, we shot a filmed sequence of weapons being loaded in a car and on a boat. This sequence was filmed at Mitchell Wer Bell's home in Powder Springs, Georgia, and both the car, a Volvo, and the boat belonged to Wer Bell. The weapons consisted of about a dozen or so Enfield 30 caliber rifles and about a half-dozen 38 Special two barrel over-and-under Roehm Derringers.

This film sequence was shot by Wilson. There was some sound also as I recall, but Wer Bell's face was never photographed. Mostly the shots consisted of Wer Bell's hands loading rifles into the trunk of the car and into a box on the boat. We also filmed some scenes of Wer Bell's car towing the boat on a highway in the vicinity of Powder Springs. Georgia.

Immediately upon completing the filming of the loading sequence, Jay McMullen and his crew departed for Miami leaving me with the car, boat and Wer Bell. I was to accompany a Haitian driver on the trip south to Miami supposedly towing the boat containing the weapons. My job was to film the travel sequence, tape record an interview with the Haitian driver during the trip and also to record news and weather from the radio in the car during the course of the trip for purposes of time and location identification on sound. The only problem was that St. George did not provide a Haitian driver for the trip. The interview of the "Haitian driver" took place a few days later, in Miami and was simulated to make it sound like it took place during the actual transportation of the car and boat from Powder Springs, Georgia to Miami.

(5) Philip Agee, Terrorism and Civil Society as Instruments of US Policy in Cuba (2004)

Warren Hinkle and William Turner, in The Fish is Red, easily the best book on the CIA's war against Cuba during the first 20 years of the revolution, tell the story of the CIA's efforts to save the life of one of their Batista Cubans. It was March 1959, less than three months after the revolutionary movement triumphed. The Deputy Chief of the CIA's main Batista secret police force had been captured, tried and condemned to a firing squad. The Agency had set up the unit in 1956 and called it the Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities or BRAC for its initials in Spanish. With CIA training, equipment and money it became arguably the worst of Batista's torture and murder organizations, spreading its terror across the whole of the political opposition, not just the communists.

The Deputy Chief of BRAC, one José Castaño Quevedo, had been trained in the United States and was the BRAC liaison man with the CIA Station in the US Embassy. On learning of his sentence, the Agency Chief of Station sent a journalist collaborator named Andrew St. George to Che Guevara, then in charge of the revolutionary tribunals, to plead for Castaño's life. After hearing out St. George for much of a day, Che told him to tell the CIA chief that Castaño was going to die, if not because he was an executioner of Batista, then because he was an agent of the CIA. St. George headed from Che's headquarters in the Cabaña fortress to the seaside US Embassy on the Malecón to deliver the message. On hearing Che's words the CIA Chief responded solemnly, "This is a declaration of war." Indeed, the CIA lost many more of its Cuban agents during those early days and in the unconventional war years that followed.

Today when I drive on 31st Avenue on the way to the airport, just before turning left at the Marianao military hospital, I pass on the left a large, multi-story white police station that occupies an entire city block. The style looks like 1920's fake castle, resulting in a kind of giant White Castle hamburger joint. High walls surround the building on the side streets, and on top of the walls at the corners are guard posts, now unoccupied, like those overlooking workout yards in prisons. Next door, separated from the castle by 110th street, is a fairly large two-story green house with barred windows and other security protection. I don't know its use today, but before it was the dreaded BRAC Headquarters, one of the CIA's more infamous legacies in Cuba. The same month as the BRAC Deputy was executed, on March 10, 1959, President Eisenhower presided over a meeting of his National Security Council at which they discussed how to replace the government in Cuba. It was the beginning of a continuous policy of regime change that every administration since Eisenhower has continued.

As I read of the arrests of the 75 dissidents, 44 years to the month after the BRAC Deputy's execution, and saw the US government's outrage over their trials and sentences, one phrase from Washington came to mind that united American reactions in 1959 with events in 2003: "Hey! Those are OUR GUYS the bastards are screwing!"

A year later I was in training at a secret CIA base in Virginia when, in March 1960, Eisenhower signed off on the project that would become the Bay of Pigs invasion. We were learning the tricks of the spy trade including telephone tapping, bugging, weapons handling, martial arts, explosives, and sabotage. That same month the CIA, in its efforts to deny arms to Cuba prior to the coming exile invasion, blew up a French freighter, Le Coubre, as it was unloading a shipment of weapons from Belgium at a Havana wharf. More than 100 died in the blast and in fighting the fire afterwards. I see the rudder and other scrap from Le Coubre, now a monument to those who died, every time I drive along the port avenue passing Havana's main railway station.

In April the following year, two days before the Bay of Pigs invasion started, a CIA sabotage operation burned down El Encanto, Havana's largest department store where I had shopped on my first visit here in 1957. It was never rebuilt. Now each time I drive up Galiano in Central Havana on my way for a meal in Chinatown, I pass Fe del Valle Park, the block where El Encanto stood, named for a woman killed in the blaze.

Some who signed statements condemning Cuba for the dissidents' trials and the executions of the hijackers know perfectly well the history of US aggression against Cuba since 1959: the murder, terrorism, sabotage and destruction that has cost nearly 3,500 lives and left more than 2,000 disabled. Those who don't know can find it in Jane Franklin's classic historical chronology The Cuban Revolution and the United States.

One of the best sum-ups of the US terrorist war against Cuba in the 1960's came from Richard Helms, the former CIA Director, when testifying in 1975 before the Senate Committee investigating the CIA's attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro. In admitting to "invasions of Cuba which we were constantly running under government aegis," he added:

"We had task forces that that were striking at Cuba constantly. We were attempting to blow up power plants. We were attempting to ruin sugar mills. We were attempting to do all kinds of things in this period. This was a matter of American government policy."

During the same hearing Senator Christopher Dodd commented to Helms: "It is likely that at the very moment that President Kennedy was shot, a CIA officer was meeting with a Cuban agent in Paris and giving him an assassination device to use against Castro."

Helms responded: "I believe it was a hypodermic syringe they had given him. It was something called Blackleaf Number 40 and this was in response to AMLASH's request that he be provided with some sort of a device providing he could kill Castro. I'm sorry that he didn't give him a pistol. It would have made the whole thing a whole lot simpler and less exotic."

Review the history and you will find that no US administration since Eisenhower has renounced the use of state terrorism against Cuba, and terrorism against Cuba has never stopped. True, Kennedy undertook to Khrushchev that the US would not invade Cuba, which ended the 1962 missile crisis, and his commitment was ratified by succeeding administrations. But the Soviet Union disappeared in 1991 and the commitment with it.

Cuban exile terrorist groups, mostly based in Miami and owing their skills to the CIA, have continued attacks through the years. Whether or not they have been operating on their own or under CIA direction, US authorities have tolerated them.

As recently as April 2003 the Sun-Sentinel of Ft. Lauderdale reported, with accompanying photographs, exile guerrilla training outside Miami by the F-4 Commandos, one of several terrorist groups currently based there, along with remarks by the FBI spokeswoman that Cuban exile activities in Miami are not an FBI priority. Abundant details on exile terrorist activities can be found with a web search including their connections with the paramilitary arm of the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF).

(6) Christopher J. Petherick, Congress Ignores Money Laundering By Biggest Bankers, American Free Press (2004)

In a series of groundbreaking reports, the late Spotlight diplomatic correspondent Andrew St. George exposed trillions of dollars of dirty money dealings involving the world’s largest financial organizations, including David Rockefeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank, Citibank and the Bank of New York.

St. George reported that the Senate Permanent Sub committee on Investigations headed by Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) quietly probed the underbelly of illicit financial transactions in two brief committee hearings in November 1999 but quickly dropped the issue when it was learned just what they had unearthed.

“Wall Street’s private banks are estimated to hide an eye-popping $21.5 trillion in such deviously deodorized deposits, according to an unpublished estimate by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development,” St. George wrote under the pseudonym, Martin Mann, in the Dec. 6, 1999, issue of The Spotlight.

However, St. George wrote, “the Senate’s money-laundering hearings shied away from exploring such potentially explosive issues.”

Despite the bad publicity, banks fervently resisted legislation that sought to close the loopholes which allow trillions of dollars of illicit money made off of drugs and arms smuggling to be sanitized through “reputable” banks in countries with loose banking regulations such as Israel, Belize and the Cayman Islands.

In addition, the Federal Reserve, the official watchdog of the US banking system, has taken lightly existing initiatives intended to clamp down on suspect transactions that would cut off a steady supply of cash from questionable sources, banking experts have complained. But the Fed has a history of overlooking massive corruption, according to St. George.

(7) Sean O'Hagan, Che Guevara, The Observer (11th July, 2004)

Rene Burri photographed Che in Havana in 1963, just months after the Cuban missile crisis. Che was being interviewed by an American woman from Look magazine. 'I was in his tiny office for three hours, the blinds closed throughout, and Che was pacing the room like a caged tiger. The interview was like a cockfight between Communism and capitalism, and he was strutting and angry, hectoring this woman, and chomping on his cigar. Suddenly, he looked straight at me and said, "So, you are with Magnum. If I catch up with your friend Andy, I'll cut his throat", and he drew his finger slowly across his throat.' Andy was Andrew St George, another Magnum photographer, who had travelled with Che in the Sierra Maestra, and then later filed reports for American intelligence. 'Che was fired up that day' says Burri, 'and he was maybe a showman, but it scared the hell out of me. I knew then, this was a man who was not cut out to be a politician, he was a soldier and a killer.'

(8) Michael Collins Piper, Existence of Secret WWII Gold Horde Confirmed (2003)

During the mid-1980s, international correspondent Andrew St. George and a team of investigative reporters working for The Spotlight newspaper astounded many of its readers by challenging a legend then-popular in the "mainstream" media in America: the theory that former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos and his colorful wife Imelda had stolen billions of dollars from their nation's treasury, and much of it from U.S. foreign aid to the Asian republic.

Now-nearly 20 years after the fact-the exclusive reports by St. George and his Spotlight team have been confirmed by an unlikely source: veteran writer Sterling Seagrave, a well-known authority on the Far East and an unabashed critic of the Marcos regime.

In a new book, Gold Warriors: America's Secret Recovery of Yamashita's Gold, Seagrave and his co-author (his wife, Peggy) have affirmed virtually all of what The Spotlight reported about Marcos and his rise to power-and of his ultimate ouster, including the reasons why.

But even more than that, the Seagraves have outlined the existence of an extraordinary hidden cache of gold-looted by infamous Japanese warlord Yamashita Tomoyuki from the nations of Asia prior to and during World War II-much of which (but not all) was later seized by American forces and used to fund what was called the Black Eagle Trust, a multinational covert operations treasure chest utilized during the Cold War and up until, apparently, even today. And yes, Marcos himself recovered a big chunk of the treasure. This was, as The Spotlight said to much criticism, the real source of his wealth.

Big names such as former US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, John J. McCloy, head of the World Bank, General Edward Lansdale and others are just a few of the familiar figures whose roles in the shadowy Black Eagle Trust are recounted by the Seagraves. The tentacles of this massive treasure reach throughout the big banks of the world today and its economic impact has never before been outlined in such amazing detail.

It seems that no American president has been in the dark about the existence of this gold horde-much of which still remains hidden, buried, in the Philippine islands and elsewhere in the Pacific and which is still the subject of wide-ranging treasure hunts.

According to the Seagraves, as late as March 2001-in the early weeks of the newly-minted George W. Bush administration, associates of the Bush family were evidently deeply involved in the treasure-hunting and in efforts to profit from the sale and transfer of the recovered treasure. And what is of particular note is that, so say the Seagraves, two US Navy ships were being utilized in the effort.

What about the Marcos connection? The Spotlight asserted that Marcos's actual wealth-in unaccounted billions-stemmed from the fact that Marcos had actually recovered a large cache of the hidden gold in the days following the end of World War II. Critics said The Spotlight was wrong and that Marcos had actually stolen billions from his nation's treasury. Now, however, the Seagraves cite no less an authority than retired General John Singlaub, a vaunted hero of both World War II and Korea who finished up his career as the top US military commander in Korea, dismissed by then-President Jimmy Carter.

Singlaub actually became quite active in the covert American efforts to recover the "Yamashita treasure" and, according to Singlaub, "I knew from past experience that stories of buried Japanese gold in the Philippines were legitimate. Marcos's $12 billion fortunate actually came from [this] treasure, not skimmed-off US aid. But Marcos had only managed to rake off a dozen or so of the biggest sites. That left well over a hundred untouched."

This, of course, means that Yamashita's gold-which amounts to certainly hundreds of billions in value, probably trillions-was a real source of power and influence for Marcos and, in the end, proved not only to be a source of his rise to power, but, ultimately, his undoing.

The Seagraves relate-echoeing The Spotlight-that when Marcos demanded a higher-than-usual commission for lending a portion of his gold horde to the Reagan administration in order to prop up a Reagan scheme to manipulate the world gold market, this was the beginning of Marcos' downfall. As a consequence, then US CIA-Director William Casey set in motion the riots and protests that began creating trouble for Marcos in the streets of Manila.

(9) Martin Mann (Andrew St George), The Spotlight (14th August, 2000)

George W. Bush and Richard Cheney, the Republican presidential and vice presidential candidates, known in Washington as the "oil ticket" for their intimate connections to the petroleum industry, may face worse corruption scandals in coming months than the lewd, mendacious and cash-hungry Clinton administration ever did. The Spotlight has learned from European and US investigative sources.

As Cheney, a millionaire petroleum executive who served as defense secretary in the administration of George Bus, the candidate's father, rose to accept the vice-presidential nomination from the cheering Republican convention in Philadelphia, Swiss prosecutors quietly moved to impound over $130 million in allegedly laundered funds deposited in Swiss banks.

According to preliminary findings of the Swiss inquiry, the frozen funds represent under-the-table payoffs slipped to the top government officials of Kazakhstan by giant US petroleum companies seeking favored access to that oil-rich country, a former Soviet province that attained independence after the collapse of communism.

Adised by Swiss authorities that the suspect acounts - more than $85 million found hidden in private numbered accounts controlled by Kazakh President Nursultan A. Nazarbayev in a single Geneva bank, Banque Pictet - may violate the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, federal authorities in New York launched an investigation of their own.

The US probe quickly focused on James H. Giffen, head of the Mercator Corporation, known as an influential American financial advisor to Nazarbayev.

Last month, the Justice Department sent Swiss chief prosecutor Daniel Devaud a confidential memorandum naming Giffen and his public-relations company as targets of a formal federal criminal investigation.

According to this memorandum, the Giffen probe was triggered by the findings of FBI agents in New York indicating that the millions impounded at Banque Pictet and other Swiss money-centers represented illegal payoffs to Kazakh officials by three major US oil companies: Exxon Mobil, BP Amoco, and Phillips Petroleum.

Giffen's alleged role was that of the go-between who secretly transferred these huge bribes from the US oil corporations along circuitous international money-laundering routes to Kazakhstan's president and his top aides.

Spokespersons for Exxon Mobil, BP Amoco and Phillips Petreleum have denied any wrongdoing. Mark J.

MacDougal, a Washington lawyer for Giffen also denied the charges.

But the Swiss-American inquiry is continuing. If it turns up solid evidence of bribery by US oil interests - sources close to the case call it "the most likely outcome" -- the next time-bomb of a question will be: How many other petroleum potentates are soiled by this sordid affair?

Until he was offered - and accepted - the Republican vice-presidential nomination this month, Cheny served as president of the Halliburton Corporation, the world's largest oil-service, exploration and engineering outfit.

A number of Halliburton's field operations have been linked to Exxon Mobil's and BP Amoco's overseas ventures in recent years. Investigators are poised to explore whether these links involved any operations in corruption-riddled Kazakhstan.

Washington is buzzing with excited rumors that some major Bush campaign contributors - long time cronies of the presidential candidate - will face not just stinging embarrassment but criminal indictment when these cases hit the headlines, especially if the Republicans fail to gain the White House this fall.

(10) Jean St. George, email to John Simkin (8th February, 2007)

I am the widow of Andrew St. George. We were married for nearly 50 years. He never, ever, was a officer or agent of the CIA. The quote in Warren Hinkle's book is a total and complete falsehood. My husband may have made a joke - about the suspicion's that he worked for the CIA - to Warren over a beer or two, but never said such a thing seriously. After the end of World War II,he did work for U.S. Army Intelligence in Austria. His family - parents and younger brother - depended on him for their survival after the War. He had been anewspaper reporterin Budapest, and got out of the Army as soon as was feasible, in order to get back to his true vocation, which was journalism.The CIA in Cuba came to him and asked him to intervene wilth Che Guevara on behalf of Sr. Quevado. After the horrors of WW II - during which he had worked with Raoul Wallenberg and the Hungarian underground - he became a passionate anti-death-penalty advocate, and would have tried to save the life of any living creature if he could. (I could tell youstories about a mouse-in-the-bathtub, Canada geese in the park, spiders in the kitchen, etc.) It ended his friendship with Che, and they both felt badly about it. Che retaliated by accusing him of working for the FBI. The notion that the United States government would send a non-Spanish speaking Magyar to spy on Castro is pretty silly. The basis of the friendship between my husband and Che was the fact that they both spoke French. It was the only way my husband could communicate with the guerrillas on the occasion of his first trip into the Sierra Maestra. (The editor who assigned him to the story for Cavalier Magazine, thought he had a Spanish accent!)

The CIA disliked Andrew St. George intensely for the things that he wrote about them, and tried to discredit him by suggesting that he was "one of them." Miles Copeland wrote that this was a CIA tactic. As we all know, it is against the law for the CIA to identify the people who work for them.