Lucy Townsend

Lucy Jesse, the daughter of William Jesse, a Church of England clergyman in West Bromwich, was born on 25th July 1781. On 6th July 1807 she married the Revd Charles Townsend, rector of Calstone, Wiltshire. Over the next few years Lucy gave birth to three daughters and three sons. (1)

After the passing of Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. In fact, the situation became worse. Now that the supply had officially ceased, the demand grew and with it the price of slaves. For high prices the traders were prepared to take the additional risks. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea. (2)

Women and Anti-Slavery Organisations

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. A new organisation, The Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions was formed in 1823. However, there were no women in the leadership of the organisation.

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend wrote to Thomas Clarkson and asked how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society. (3)

Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Lucy Townsend in a letter that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions." (4)

Lucy Townsend and the Female Society for Birmingham

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). (5) The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions." (6)

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America". (7)

Lucy Townsend's close friend, Mary Lloyd, a woman she had met at meetings of the Bible Society, became joint secretary of the society. Aged 30, this was the beginning of a long career of public service. Over the next few years she gave birth to ten children as well as being active in the Juvenile Society for the Deaf, set up a Benevolent Society to benefit poor mothers and a Provident Society to encourage the poor to save. Eventually she became a travelling minister in the Society of Friends. (8)

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery. (9)

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. William Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture". (10)

However, George Stephen disagreed with Wilberforce on this issue and claimed that their energy was vital in the success of the movement: "Ladies Associations did everything... They circulated publications; they procured the money to publish; they talked, coaxed and lectured: they got up public meetings and filled our halls and platforms when the day arrived; they carried round petitions and enforced the duty of signing them... In a word they formed the cement of the whole anti-slavery building - without their aid we never should have kept standing." (11)

Propaganda Campaign

The Female Society for Birmingham played an important role in the propaganda campaign against slavery. Lucy Townsend, wrote the anti-slavery pamphlet To the Law and to the Testimony (1832). "Under Lucy Townsend's and Mary Lloyd's leadership the society developed the distinctive forms of female anti-slavery activity, involving an emphasis on the sufferings of women under slavery, systematic promotion of abstention from slave-grown sugar through door-to-door canvassing, and the production of innovative forms of propaganda, such as albums containing tracts, poems, and illustrations, embroidered anti-slavery workbags." (12)

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition. (13)

Sarah Wedgwood was an active member of the group. Her husband, Josiah Wedgwood had asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands and included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" This image was "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks". (14)

Thomas Clarkson explained: "Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and this fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom." (15)

Hundreds of these images were produced. Benjamin Franklin suggested that the image was "equal to that of the best written pamphlet".Men displayed them as shirt pins and coat buttons. Whereas women used the image in bracelets, brooches and ornamental hairpins. In this way, women could show their anti-slavery opinions at a time when they were denied the vote. Sophia Sturge, a member of the Female Society for Birmingham group were responsible for designing their own medal, "Am I Not a Slave And A Sister?" (16)

Richard Reddie has argued that during this period women such as Lucy Townsend emerged "out of the shadows" after the retirement of William Wilberforce, to play an important role in the anti-slavery campaign. These women "clearly identified with the plight of disenfranchised Africans" and claimed that "African women largely bore the brunt of abuses throughout chattel enslavement - rape and other violations were common occurrences on slave ships and plantations". (17) Vron Ware, explained in her book, Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism and History (1992), that women's abolitionist women's literature was often quite explicit about the "indecencies" that women slaves endured. (18)

Slavery Abolition Act

Lucy Townsend and the other members of the Female Society for Birmingham were overjoyed by the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned. (19)

While anti-slavery was her main concern Lucy Townsend was also involved in a variety of other voluntary activities. With Mary Lloyd she established the Juvenile Association for West Bromwich and Wednesbury in Aid of Uninstructed Deaf Mutes in 1834. She was also involved in campaigns to abolish bull baiting and other cruel sports. She also acted as joint secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, and combined support for the universal abolition movement with support for educational work among freed slaves. (20)

Attempts were made to stop women delegates from taking part in the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. Two American delegates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, like the British women at the convention, were refused permission to speak at the meeting. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women." (21)

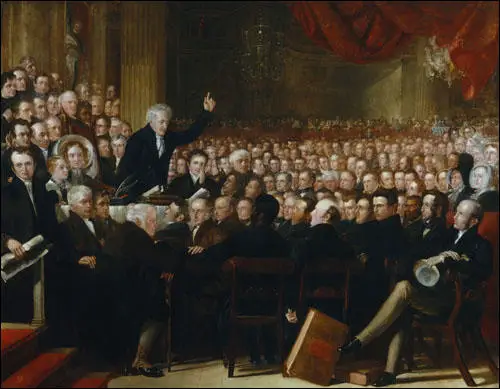

Anne Knight attempted to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention held at Exeter Hall in London, in June 1840 but as a woman was refused attendance. She became aware that the artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, had started a group portrait of those involved in the fight against slavery. She wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend complaining about the lack of women in the painting. "I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement." (22)

When the painting was completed it did not include Lucy Townsend or most of the leading female campaigners against slavery. Clare Midgley, the author of Women Against Slavery (1995) points out that as well as Anne Knight and Lucretia Mott, it does feature Elizabeth Pease, Mary Anne Rawson, Amelia Opie and Annabella Byron: "Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right." (23)

Lucy Townsend died on 20th April 1847 at the rectory at Thorpe, near Southwell, Nottinghamshire.

Primary Sources

(1) Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) page 326

Lucy Townsend, was an Evangelical Anglican from Birmingham who had been inspired as a girl by Clarkson; she wrote to him for advice on forming a women's anti-slavery society. In reply, Clarkson cautiously suggested that Townsend call her new group the "Female Society for ameliorating the condition of Female Slaves in the British Colonies, but with a view ultimately to their final emancipation there."

(2) Clare Midgley, Lucy Townsend : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The Ladies' Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the Female Society for Birmingham for the Relief of British Negro Slaves, then the Ladies' Negro's Friend Society) was founded at a meeting held at her home in West Bromwich on 8 April 1825. Lucy Townsend and Mary Lloyd, whom she had met at meetings of the Bible Society, became joint secretaries of the society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America.

Under Lucy Townsend's and Mary Lloyd's leadership the society developed the distinctive forms of female anti-slavery activity, involving an emphasis on the sufferings of women under slavery, systematic promotion of abstention from slave-grown sugar through door-to-door canvassing, and the production of innovative forms of propaganda, such as albums containing tracts, poems, and illustrations, embroidered anti-slavery workbags, and seals bearing the motto ‘Am I not a woman and a sister?’.

(3) Anne Knight wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend about the proposed painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon (20th September, 1840)

I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement.

(4) Clare Midgley, Women Against Slavery (1995)

Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)