Dickey Chapelle

Georgette Louise Meyer (Dickey Chapelle) was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on 14th March 1919. After leaving Shorewood High School she briefly attended aeronautical design classes at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. According to her biographer: "She returned home a few months later, knowing she would rather fly a plane than design one and began working at a Milwaukee airfield. When Chapelle's mother learned of her affair with a pilot, she was sent to live with her grandparents in Florida."

After working in a series of jobs in Florida, she found employment with Trans World Airlines in New York City. She attended photography evening classes run by Tony Chapelle. She eventually married Chapelle. This ended in divorce but she adopted the professional name Dickey Chapelle. She took the name "Dickey" from her favourite explorer, Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

During the Second World War she become a war correspondent photojournalist for National Geographic. In 1942 she spent time with the Marines who were on training courses in Panama. This included covering the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa with the Marines. Roberta Ostroff, the author of Fire in the Wind: The Biography of Dickey Chappelle (1992) has argued that she "was a tiny woman known for her refusal to kowtow to authority and her signature uniform: fatigues, an Australian bush hat, dramatic Harlequin glasses, and pearl earrings."

After the war, Dickey Chapelle covered all the major wars and rebellions. This included the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, where she was captured and jailed for seven weeks. This was followed by spells in Algeria and Lebanon. She later wrote in What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself (1962): "I had become an interpreter of violence. I'd covered three revolutions in three years - Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon.... I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world."

In the summer of 1958 she was sent by The Reader's Digest to cover the uprising against Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. She was not impressed with what she saw in Havana. "Around his empire of corruption, Batista built a secret police organization. The letters SIM and the sleek olive drab radio cars with submachine gun barrels poking through their windows appeared in the streets. Every police station in the large cities was said to have its own torture chamber. A fifty-year-old woman schoolteacher who during an interrogation had been violated with a soldering iron in Havana's XII district, February 24, 1958, described the building. She said the chief's office had walls of tile and drains in the floor so it could be cleaned with a hose each day."

Along with two of her fellow reporters, Herbert Matthews and Andrew St. George, she managed to interview Fidel Castro. She later recorded: "The emotional tension around him rarely lessened; he conveyed high pressure in every movement and was never still. His normal state of ease was a purposeful forty-inch stride forward, then back (it was nearly impossible to photograph him). His speaking voice was surprisingly soft and his incessant speech distinct. His manner of giving praise was a bear hug, his encouragement a heavy hand on the shoulder, his criticism an earthquake loss of temper. He reacted with Gargantuan anger to every report of dead and wounded; I considered this evidence that lie had never suffered the magnitude of losses Batista claimed.. The overwhelming fault in his character was plain for all to see even then. This was his inability to tolerate the absence of an enemy; he had to stand - or better, rant and shout-against some challenge every waking moment... In the rare times when he spoke quietly, Castro revealed a fine incisive mind utterly ill-matching the psychopathic temperament which subdued it."

After Fidel Castro gained power, Chapelle campaigned against the new government. In March 1963 she joined forces with Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Hal Hendrix, Paul Bethel, William Pawley, Virginia Prewett, Edward Teller, Arleigh Burke, Leo Cherne, Ernest Cuneo, Sidney Hook, Hans Morgenthau and Frank Tannenbaum to form the Citizens Committee to Free Cuba (CCFC).

Miller Davies, reported in the Miami Times, that Felipe Vidal Santiago saved Chappell's life in January 1964, when her boat caught fire off Key Biscayne. The newspaper reported that "Vidal Santiago, close by in his own boat rescued Miss Chapelle and rushed her to Jackson Memorial Hospital." Four months later it was reported that Santiago, a CIA agent, had been executed in Cuba.

Chapelle's anti-communism encouraged her to volunteer to cover the Vietnam War. Her early reports were highly sympathetic to the small numbers of United States military advisors in the country that were attempting to defend the Ngo Dinh Diem administration.

Chapelle passionately argued for the sending of combat troops. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson became the new president of the United States. He was a strong supporter of the Domino Theory and believed that the prevention of an National Liberation Front victory in South Vietnam was vital to the defence of the United States: "If we quit Vietnam, tomorrow we'll be fighting in Hawaii and next week we'll have to fight in San Francisco."

On 8th March, 1964, 3,500 US marines arrived in South Vietnam. They were the first "official" US combat troops to be sent to the country. This dramatic escalation of the war was presented to the American public as being a short-term measure and did not cause much criticism at the time. A public opinion poll carried out that year indicated that nearly 80% of the American public supported the bombing raids and the sending of combat troops to Vietnam.

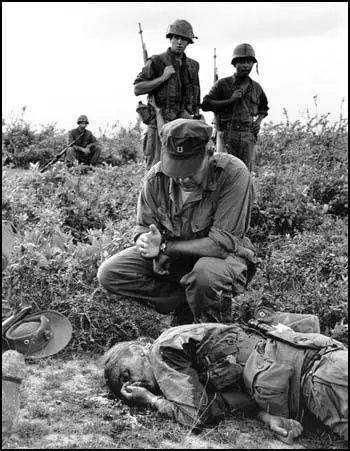

Chapelle was one of the few reporters who went with the US Army on search and destroy missions. This included Operation Black Ferret. On 4th November, 1965, t he lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire boobytrap. Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel which severed her carotid artery and died soon after. She became the first female war correspondent to be killed in action.

by Henri Heut. He was himself killed in Vietnam in 1971.

Primary Sources

(1) Dickey Chapelle, What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself (1962)

Home to me is a small apartment in a row of old buildings that face across Manhattan's First Avenue in the direction of the East River. My view of the water, though, is blocked by Bellevue Hospital, a symbol which some people call depressing but which I find is a reminder of compassion and challenge, too.

After I came back from Lebanon and sat down in the green chair behind the broad wooden table that faces the noisy typewriter, I forgot for the first time in my life to ask if I was a reporter. I was too busy telling what I had to report.

Not till thousands of words had ground through the typewriter did I begin to understand the pattern of the history I'd been covering, though. I wanted to go on thinking of the typed sheets of paper falling one after another out of the machine as just the output of a story teller, simply the product by which I made my living.

They were stories, yes. Telling them fed me, yes. But their substance was not innocent.

I had become an interpreter of violence. I'd covered three revolutions in three years-Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon. One editor summed it up far too neatly when he remarked, "You don't mind, do you, if we call you our special correspondent to the bayonet borders of the world?"

I did, but not half so much as I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world.

Three weeks later, I was sitting in a Miami hotel room staring at a telephone. As soon as it rang, I would be on my way to cover my final revolution (to date, that is) probably the most significant revolution of them all.

The people of Cuba had started to hope, too, and I'd been sent by The Reader's Digest to find out what was happening to them.

The phone did ring, finally. I heard a man's deep voice saying "Cohen here," the code which the Cuban exiles hack in New York had told me would identify the leaders of the anti-Batista movement in Miami.

I expected to be flown at once to Havana but instead I spent five days in a near-bare, cheerless tile-floored office in the Congress Building, only a few rooms away from the one where a long time ago I'd earned fifteen dollars a week as an air show city editor. The office was the clandestine headquarters of the Cuban underground in Miami supporting Fidel Castro. Hour after hour I interviewed Cubans fleeing from Batista. From their words and voices, many still shrill with fear, I tried to piece together a picture of the reign of terror.

The looting of Cuba on a lavish scale could not be hidden, and Batista first tried to anchor his critics to his cause as he had anchored the army-with a chain of gold. But not all the critics were corruptible. And stolen pesos could not dry up the rising hatred felt toward him by the people he was robbing. There simply were too many of them. So at last he decided to try to silence them by the tried-and-true method of fear.

Around his empire of corruption, Batista built a secret police organization. The letters SIM and the sleek olive drab radio cars with submachine gun barrels poking through their windows appeared in the streets. Every police station in the large cities was said to have its own torture chamber. A fifty-year-old woman schoolteacher who during an interrogation had been violated with a soldering iron in Havana's XII district, February 24, 1958, described the building. She said the chief's office had walls of tile and drains in the floor so it could be cleaned with a hose each day.

Another told me lie knew of a community destroyed by the Cuban Air Force with air-dropped flaming gasoline. He asked me almost diffidently if there was any other country that could have supplied the Bastistiano planes with the napalm-the gasoline jelly bombs-but the United States. I said I did not know, but I did not add that the answer probably was no. (Later I was to see the wreckage of the burned-out town of Mayeri in Oriente, and to photograph pieces of the distinctive silvery metal casings developed by U.S. forces during World War II for air-dropping napalm.)

In Miami, I reminded my Cuban friends that the United States had embargoed all arm shipments to Batista, including those for hemisphere defense, in March of 1958 (it was now mid-November of the same year). They derided the effect of the embargo, saying that Batista's forces had been fully equipped long before with the very weapons now being turned on Cuban civilians.

For two years Fidel Castro had been a magnet for venturesome American newsmen, an off-beat folk hero in the tales of foreign correspondents. First Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and then Andrew St. George, later of Life, had trekked deep into the Sierra Maestre mountains of Oriente Province to bring back reports that Castro's forces were taking on planes and armored cars with hunting rifles and shotguns-and winning. In the end, some twenty reporters had been assigned to go through Batista's lines to Castro. Exactly half of them made it; the rest, identified enroute by Batista's secret police, had been loaded at gunpoint onto the first Miami-bound airplane.

Dr. Carlos Busch, who headed Castro's underground in Miami, told me bluntly that I'd get through-if I let him ship my cameras and field gear into the Sierra Maestre area clandestinely. He said I was to travel as a tourist and that to carry the leather camera case containing my Leicas, boots and Kabar would expose the courier who must accompany me to arrest and torture...

Once among the winding sidestreets of the city proper, my courier delivered me to the quarters I was to occupy till I could be led to Castro: a deluxe tourist court on the outer edge of Santiago where the life of high adventure included a fine restaurant, electric light, hot and cold running water and a marathon gin rummy game in English. Other players included an oil expert on his way back home to Texas, a shellfish specimen collector from the University of Michigan and my colleague, Andrew St. George.

Andrew at once told me to beg, borrow, steal-or even buy -new cameras at once since my own certainly never would be given back to me. Although I was outraged, his advice made sense. I insisted my girl courier take the risk of driving me around the city while I, with the worst possible grace, assembled a new picture-taking outfit. I found a Japanese :.5 mm. camera in a photo store, picked up half a dozen rolls of dusty film from every drugstore we passed and finally located a Leica I could borrow from one wealthy Castro sympathizer and a lens from another. The only good thing I could tell Andrew that evening over our card game about my mismatched photo gear was that it was better than being empty-handed.

Andrew was sage again. He told me I'd probably be the only correspondent with Castro during the month; he himself was on his way to New York and other reporters had left earlier; the bearded revolutionary's campaign seemed to be stalled at the gates of Santiago. Glumly I agreed I probably was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

No doubt such mutual misjudgments are the only certainties of journalism. As matters worked out, before I left Cuba nine weeks later, I was to see a whole sequence of infantry actions, the end of the fighting and the installation of Castro in the Presidential Palace in Havana-the biggest news stories out of Cuba in many years.

My actual crossing from the city's edge into the countryside where Castro's forces already ruled was an anticlimax, an uneventful walk with another girl courier across a golf course. The jeep that met us on the far side was driven by a bearded rifleman who wore an arm patch reading 26 JULIO (the 26th of July movement commanded by Fidel Castro). After a few hours of grinding across cane fields and fording streams, I was deep into Oriente Province at the farmhouse headquarters of the forces under the orders of Fidel Castro's younger brother, Raul.

(2) Dickey Chapelle, What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself (1962)

Fidel Castro, tremendous in wet and muddy fatigues, laughed deeply as he swung back and forth in a hammock. Raul spoke shrilly and incessantly of his victories. Celia Sanchez, the woman who had been at Fidel's side for several years, hovered there now, thin and febrile in her green twill uniform with five gold religious medals swinging on chains around her neck. Vilma Espin, later to become Mrs. Raul Castro, smiled upon the company as she toyed with a new Belgian submachine gun presented to her as a token of Raul's triumphs.

In the background, but with their smiles a benediction, were two short handsome men old enough to have heavy gray in their combed beards-Hubert Matos and Eduardo Chibas, a one-time judge and a one-time lawyer now both infantry captains like their fellow-intellectual, Capitano Orlando. (To date according to the reports, Matos has been executed, Chibas is in exile and Orlando is missing.)

The normal scene in Castro's command post was less genial than my first impression but never less frenetic. Typically, it was a shifting knot of bearded officers and ragged messengers. The longer the beard, the longer its wearer had been a rebel.

The staccato rhythm of the hasty conferences, as orders were sent out and messages received, was puctuated by radio transmissions. These usually were spoken by Castro himself. He would grasp the walkie-talkie as if it were an enemy's throat and, in a voice to rouse the countryside, begin, "Urgente, urgente!" He never spoke in any kind of code and much of Cuba could follow the battles by simply tuning in on the Castro tactical transmissions.

The emotional tension around him rarely lessened; he conveyed high pressure in every movement and was never still. His normal state of ease was a purposeful forty-inch stride forward, then back (it was nearly impossible to photograph him). His speaking voice was surprisingly soft and his incessant speech distinct. His manner of giving praise was a bear hug, his encouragement a heavy hand on the shoulder, his criticism an earthquake loss of temper. He reacted with Gargantuan anger to every report of dead and wounded; I considered this evidence that lie had never suffered the magnitude of losses Batista claimed. Once, when nine of his men lead been killed at Jiguani in a single action, he insisted I go out to make close-ups of each body "so their martyrdom will not be forgotten by the world."

The overwhelming fault in his character was plain for all to see even then. This was his inability to tolerate the absence of an enemy; he had to stand - or better, rant and shout-against some challenge every waking moment. His best tactical officers used this vast appetite for hostility to their own gain. A commander who needed fresh ammunition, for instance, could be sure he would get it not by making a reasonable request but by charging up to his commander, standing rock steady and shouting up at the great bearded face, "Dr. Fidel, I tell you you have been a fool not to support me! You should have known I needed more shells!"

Like everyone else in the headquarters, I soon found my own manners conforming. If I'd heard a rumor of a jeep heading for the front but could not find it, I'd rail at any bearded officer that I was tired of having Cubans lie to me; where the devil was my jeep? Neither my illogic nor my untruthfulness mattered. Since my sincerity had been attested by my apparent Latin loss of temper, someone would go looking for a jeep.

That this twist of farce would someday lead to political tragedy - that the Reds would make of Castro's need for a powerful enemy a means of infiltrating his government, inspiring him to rattle their rockets against America long after Batista was gone-this I did not guess. Only its pathological overtones were plain.

In the rare times when he spoke quietly, Castro revealed a fine incisive mind utterly ill-matching the psychopathic temperament which subdued it. He liked to boast of his encyclopedic knowledge of the Batistiano soldiers. He said his secret weapon lay in his enemies' minds; they did not want to risk themselves for what they presumably were sworn to defend - the regime of Batista.

(3) The Dallas Morning News (22nd October, 1963)

A big Cuban exile raiding party, heavily armed and accompanied by an American woman freelance photographer, was intercepted and stopped off Miami Beach, Sunday night as it headed for Cuba, U.S. Customs officials announced Monday. There were 21 Cuban men, all members of the Commandos-L exile organization, and U.S. photographer Georgette Dickey Chapelle in the raiding expedition, which was seized aboard four boats, according to Miami customs supervisor Joseph P. Fortier. Leader of the raiders was 56 year-old Santiago Alvarez, former governor of Cuba’s Mantaza Province during the Fulgencio Batista regime.

(4) Roberta Ostroff, Fire In The Wind: The Life of Dickey Chapelle (1992)

The dramatic death of was made even more newsworthy by the fact that she was the first American woman reporter ever killed in action, as pointed out by her friend, S.L.A. “Slam” Marshall in his obit in the Los Angeles Times on November 25, 1965 Dickey was cremated and brought back to Milwaukee on November 12 by an honor guard of six marines, one of whom Staff Sergeant Albert P. Milville, had been tossed flat by the explosion and would be returning immediately to Vietnam. The honor guard was an extraordinary tribute for a civilian and a woman.