On this day on 4th February

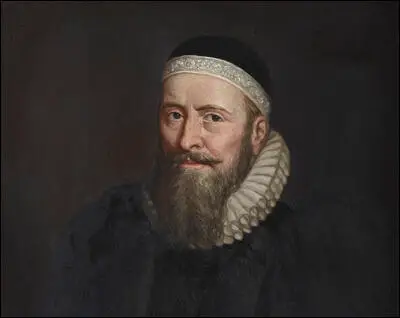

On this day in 1555 John Rogers is burned at the stake, becoming the first English Protestant martyr under Queen Mary. Rogers was born in Deritend near Birmingham in about 1500. He graduated from Pembroke College in 1526. After leaving Cambridge University he became rector 32 of the London church of Holy Trinity-the-Less.

In 1534 Rogers went to Antwerp to become chaplain to English merchants in the country. While in the city he met William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale who had both fled from England in fear of being persecuted for their religious beliefs by Henry VIII. Tyndale was living there as a guest of Thomas Poyntz, an English merchant and cousin to Lady Walsh of Little Sodbury in Gloucestershire who, with her husband, had employed Tyndale as tutor to their children in the early 1520s.

Tyndale was the author of The Obedience of a Christian Man (1528) and had translated the New Testament and the Old Testament as far as the Book of Chronicles. In May 1535 a combination of forces hostile to reform, including the Emperor Charles V, succeeded in having Tyndale arrested just outside the English House, and had him imprisoned. Some of Tyndale's manuscripts were confiscated but Rogers managed to rescue some of his work, including translations of some of the Old Testament.

Rogers worked with Miles Coverdale to use Tyndale's manuscripts to assemble a complete Bible. Fifteen hundred copies of Tyndale's Bible were printed and shipped to England. Rogers arranged for the English Bible to be printed in Antwerp in 1537. A copy was given to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. He sent it to Thomas Cromwell with the note "as for the translation, so far as I have read thereof I like it better than any other translation heretofore made".

The two men wanted the Bible to be available in English. This was a controversial issue as William Tyndale had been denounced as a heretic by Henry VIII eleven years before, for producing such a Bible. Therefore, the Bible did not have Tyndale's name on it and instead was attributed to Thomas Matthew.

On 4th August 1538, Cranmer asked Cromwell to present it to the king in the hope of securing royal authority for it to be available in England. Henry agreed to the proposal on 30th September. Every parish had to purchase and display a copy of the Bible in the nave of their church for everybody who was literate to read it. "The clergy was expressly forbidden to inhibit access to these scriptures, and were enjoined to encourage all those who could do so to study them." Cranmer was delighted and wrote to Cromwell praising his efforts and claiming that "besides God's reward, you shall obtain perpetual memory for the same within the realm." Bishop Stephen Gardiner was totally opposed to this measure as he considered the departure from the "original" Latin was heresy.

While in Antwerp John Rogers married Adriana de Weyden. John Foxe described her as "more richly endowed with virtue and soberness of life, than with worldly treasures". In 1540 the couple moved to Wittenberg. In 1543 he became pastor at Meldorf. During this period Philipp Melanchthon, a follower of Martin Luther, described Rogers as "a learned man… gifted with great ability, which he sets off with a noble character… he will be careful to live in concord with his colleagues… his integrity, trustworthiness and constancy in every duty make him worthy of the love and support of all good men."

In January 1547 Edward VI came to the throne and the following year he returned to London. Soon afterwards Joan Bocher, an Anabaptist, began distributing pamphlets, that expressed the opinion that Christ, the perfect God, had not been born as a man to the Virgin Mary. She was arrested and brought to trial before Bishop Nicholas Ridley and found guilty of heresy. Boucher's views upset both Catholics and Protestants. John Rogers was brought in to persuade her to recant. After failing in his mission he declared that she should be burnt at the stake.

John Foxe, who had been active in opposing the burning of heretics during the reign of Henry VIII was very distressed that Joan Bocher was now to be burned under the Protestant government of Edward VI. Although he disagreed with her views he thought that the life of "this wretched woman" should be spared and suggested that a better way of dealing with the problem was to imprison her so that she could not propagate her beliefs. Rogers insisted that she must die. Foxe replied she should not be burned: "at least let another kind of death be chosen, answering better to the mildness of the Gospel." Rogers insisted that burning alive was gentler than many other forms of death. Foxe took Rogers' hand and said: "Well, maybe the day will come when you yourself will have your hands full of the same gentle burning."

It has been claimed by Christian Neff that the 12-year-old King Edward at first refused to sign the death warrant. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer insisted that "she should be punished with death for her heresy according to the law of Moses".He is said to have told Cranmer with tears, "Cranmer, I will sign the verdict at your risk and responsibility before God’s judgment throne." Cranmer was deeply impressed, and he tried once more to induce her to recant but she still refused.

Joan Bocher was burnt at Smithfield on 2nd May 1550. "She died still upbraiding those attempting to convert her, and maintaining that just as in time they had come to her views on the sacrament of the altar, so they would see she had been right about the person of Christ. She also asserted that there were a thousand Anabaptists living in the diocese of London."

On 13th May 1550, Rogers became vicar of one of the leading London churches, St Sepulchre. On 27th August 1551 he received from Bishop Nicholas Ridley the prebend of St Pancras in St Paul's Cathedral. "He was appointed lecturer in divinity in the cathedral. Ridley admired him. He preached powerfully and boldly against the misuse of the abbey lands by Northumberland and his party. In April 1552 his wife and those children born in Germany, including John Rogers and Daniel Rogers, were naturalized."

In April 1552 Edward VI fell ill with a disease that was diagnosed first as smallpox and later as measles. He made a surprising recovery and wrote to his sister, Elizabeth, that he had never felt better. However, in December he developed a cough. Elizabeth asked to see her brother but John Dudley, the lord protector, said it was too dangerous. In February 1553, his doctors believed he was suffering from tuberculosis. In March the Venetian envoy saw him and said that although still quite handsome, Edward was clearly dying. Edward's heir was Mary, the daughter of Catherine of Aragon and a Roman Catholic.

Edward died on 6th July, 1553. Three days later one of Northumberland's daughters came to take Lady Jane Grey to Syon House, where she was ceremoniously informed that the king had indeed nominated her to succeed him. Jane was apparently "stupefied and troubled" by the news, falling to the ground weeping and declaring her "insufficiency", but at the same time praying that if what was given to her was "‘rightfully and lawfully hers", God would grant her grace to govern the realm to his glory and service.

Mary, who had been warned of what John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, had done and instead of going to London as requested, she fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces."

Mary summoned the nobility and gentry to support her claim to the throne. Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's."

The problem for John Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church.

Mary decided to remove from power all those who were considered to be Protestants. John Rogers was accused of being a seditious preacher and the Privy Council ordered his arrest. Rogers stayed a prisoner in his house for five months. Some of his religious friends escaped to Europe but Rogers insisted on staying in London to defend his beliefs. On 27th January 1554 he was sent to Newgate Prison. His biographer, David Daniell, points out: "He (John Rogers) was not permitted to receive any stipend, though by law he was still incumbent of St Sepulchre. His wife and ten children were in desperate need. He remained in Newgate for a year, untried. In November or December 1554 he joined with his fellow prisoners in writing a letter to the queen, protesting against the illegality of their imprisonment and begging to be brought to trial."

In December 1554 parliament re-enacted legislation permitting the execution of heretics, and on 22nd January 1555 John Rogers was put on trial before Bishop Stephen Gardiner. Rogers was accused of heresy in denying the Papal Supremacy over the Church and the Real Presence of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine of the Sacrament. Rogers was attacked for having a wife and eleven children. He defended his decision to marry by arguing that the Bible did not say that priests should not have a wife. Rogers was also criticised for "misusing the gifts of learning which God had given them by arguing for a wicked cause against God's truth".

John Rogers was found guilty of heresy. Rogers told the commissioners that he had only one request to make, and asked that before he was burned he should be permitted to receive one farewell visit from his wife. His request was denied and on 4th February 1555 he was degraded by Bishop Edmund Bonner. This process has been explained by Jasper Ridley, the author of Bloody Mary's Martyrs (2002): "The hands were scraped with a knife to remove the holy oil with which they had been anointed. The scraping could be done either gently or roughly. The Protestants alleged that Bonner did it roughly whenever he took part in a degradation ceremony; but this may have been Protestant propaganda, for Bonner's attitude varied between boisterous and aggressive gloating and a patient attempt to persuade heretics to recant so that their lives could be spared."

On 4th February, 1555, John Rogers was taken to Smithfield. His wife and children met him on the way to the burning, but Rogers still refused to recant. He told Sheriff Woodroofe: "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Woodroofe replied: "Then, you are a heretic. That will be known on the day of judgment." Just before the burning began a pardon arrived. However, Rogers refused to accept it and became the first martyr to suffer death during the reign of Queen Mary.

It was claimed that when the fire took hold of his body, "he, as one feeling no smart, washed his hands in the flame, as though it had been in cold water" and "lifting up his hands to heaven he did not move them again until they were consumed in the devouring fire". Protestants rejoiced in his faithfulness and even Catholic opponents noted his heroic fortitude in death.

On this day in 1685 John Evelyn writes in his diary about why Charles II was a bad king. "He (Charles II) was a prince of many virtues, and many great imperfections. He would doubtless have been an excellent prince had he been less addicted to women. He had many great faults... He neglected the needs of the people... Wars, plagues, fires made his reign very troublesome and unprosperous."

John Evelyn was born in Wotton, Surrey, on 31st October 1620. He spent most of his early life in Lewes, Sussex. After being educated at Balliol College, Oxford, he spent several years travelling in Europe.

Evelyn was a supporter of Charles I and after his execution in 1649 he went into exile. He returned in 1652 and eventually became a fellow of the Royal Society. A royalist, Evelyn described the return of Charles II to London: There were 20,000 soldiers... shouting with joy; the streets covered with flowers, the bells ringing, fountains running with wine."

After the Restoration Evelyn joined the royal court of the king. On 17th October 1660 he described the executions of some of the leaders of the Commonwealth: "The traitors executed were Scroop, Cook and Jones. I did not see their execution, but met their quarters mangled and cut and reeking as they were brought from the gallows in baskets."

In 1661 he published a book on pollution, The Inconvenience of the Air and Smoke of London Dissipated. This was followed by A Disclosure of Forest Trees (1664). After the Great Fire of London in 1666 Evelyn submitted proposals for the rebuilding of the capital. He also published Navigation and Commerce (1674).

John Evelyn died on 27th February, 1706. His diaries covering the years 1641-1706 were found in an old clothes-basket in 1817 and provide vivid portraits of public figures of the period.

On this day in 1846 Charles Dickens writes an article on ragged schools in the The Daily News.

I offer no apology for entreating the attention of the readers of the Daily News to an effort which has been making for some three years and a half, and which is making now, to introduce among the most miserable and neglected outcasts in London, some knowledge of the commonest principles of morality and religion; to commence their recognition as immortal human creatures, before the Gaol Chaplain becomes their only schoolmaster; to suggest to Society that its duty to this wretched throng, foredoomed to crime and punishment, rightfully begins at some distance from the police office, and that the careless maintenance from year to year, in this the capital city of the world, of a vast hopeless nursery of ignorance, misery, and vice: a breeding place for the hulks and jails: is horrible to contemplate.

This attempt is being made, in certain of the most obscure and squalid parts of the Metropolis; where rooms are opened, at night, for the gratuitous instruction of all comers, children or adults, under the title of Ragged Schools. The name implies the purpose. They who are too ragged, wretched, filthy, and forlorn, to enter any other place: who could gain admission into no charity school, and who would be driven from any church door; are invited to come in here, and find some people not depraved, willing to teach them something, and show them some sympathy, and stretch a hand out, which is not the iron hand of law, for their correction.

Before I describe a visit of my own to a Ragged School, and urge the readers of this letter for God's sake to visit one themselves, and think of it (which is my main object), let me say, that I know the prisons of London well. That I have visited the largest of them, more times than I could count; and that the children in them are enough to break the heart and hope of any man. I have never taken a foreigner or a stranger of any kind, to one of these establishments, but I have seen him so moved at sight of the child offenders, and so affected by the contemplation of their utter renouncement and desolation outside the prison walls, that he has been as little able to disguise his emotion, as if some great grief had suddenly burst upon him. Mr. Chesterton and Lieutenant Tracey (than whom more intelligent and humane Governors of Prisons it would be hard, if not impossible, to find) know, perfectly well, that these children pass and repass through the prisons all their lives; that they are never taught; that the first distinctions between right and wrong are, from their cradles, perfectly confounded and perverted in their minds; that they come of untaught parents, and will give birth to another untaught generation; that in exact proportion to their natural abilities, is the extent and scope of their depravity; and that there is no escape or chance for them in any ordinary revolution of human affairs. Happily, there are schools in these prisons now. If any readers doubt how ignorant the children are, let them visit those schools, and see them at their tasks, and hear how much they knew when they were sent there. If they would know the produce of this seed, let them see a class of men and boys together, at their books (as I have seen them in the House of Correction for this county of Middlesex), and mark how painfully the full grown felons toil at the very shape and form of letters, their ignorance being so confirmed and solid. The contrast of this labour in the men, with the less blunted quickness of the boys; the latent shame and sense of degradation struggling through their dull attempts at infant lessons; and the universal eagerness to learn, impress me, in this passing retrospect, more painfully than I can tell.

For the instruction, and as a first step in the reformation, of such unhappy beings, the Ragged Schools were founded. I was first attracted to the subject, and indeed was first made conscious of their existence, about two years ago, or more, by seeing an advertisement in the papers dated from West Street, Saffron Hill, stating "That a room has been opened and supported in that wretched neighbourhood for upwards of twelve months, where religious instruction had been imparted to the poor", and explaining in a few words what was meant by Ragged Schools as a generic term, including, three, four or five similar places of instruction. I wrote to the masters of this particular school to make some further enquiries, and went myself soon afterwards.

It was a hot summer night; and the air of Field Lane and Saffron Hill was not improved by such weather, nor were the people ill those streets very sober or honest company. Being unacquainted with the exact locality of the school, I was fain to make some inquiries about it. These were very jocosely received in general; but everybody knew where it was, and gave the right direction to it. The prevailing idea among the loungers (the greater part of them the very sweepings of the streets and station houses) seemed to be, that the teachers were quixotic, and the school upon the whole "a lark". But there was certainly a kind of rough respect for the intention, and (as I have said) nobody denied the school or its whereabouts, or refused assistance in directing to it.

It consisted at that time of either two or three - I forget which - miserable rooms, upstairs in a miserable house. In the best of these, the pupils in the female school were being taught to read and write; and though there were among the number, many wretched creatures steeped in degradation to the lips, they were tolerably quiet, and listened with apparent earnestness and patience to their instructors. The appearance of this room was sad and melancholy, of course - how could it be otherwise! - but, on the whole, encouraging.

The close, low, chamber at the back, in which the boys were crowded, was so foul and stifling as to be, at first, almost insupportable. But its moral aspect was so far worse than its physical, that this was soon forgotten. Huddled together on a bench about the room, and shown out by some flaring candles stuck against the walls, were a crowd of boys, varying from mere infants to young men; sellers of fruit, herbs, lucifer-matches, flints; sleepers under the dry arches of bridges; young thieves and beggars - with nothing natural to youth about them: with nothing frank, ingenuous, or pleasant in their faces; low-browed, vicious, cunning, wicked; abandoned of all help but this; speeding downward to destruction; and unutterably ignorant.

This, Reader, was one room as full as it could hold; but these were only grains in sample of a Multitude that are perpetually sifting though these schools, in sample of a Multitude who had within them once, and perhaps have now, the elements of men as good as you or I, and maybe infinitely better; iii sample of a Multitude among whose doomed and sinful ranks (oh, think of this, and think of them!) the child of any man upon this earth, however lofty his degree, must, as by Destiny and Fate, be found, if, at its birth, it were consigned to such an infancy and nurture, as these fallen creatures had!

This was the Class I saw at the Ragged School. They could not be trusted with books; they could only be instructed orally; they were difficult of reduction to anything like attention, obedience, or decent behaviour; their benighted ignorance in reference to the Deity, or to any social duty (how could they guess at any social duty" being so discarded by all social teachers but the gaoler and the hangman!) was terrible to see. Yet, even here, and among these, something had been done already. The Ragged School was of recent date and very poor; but it had inculcated some association with the name of the Almighty, which was not an oath, and had taught them to look forward in a hymn (they sang it) to another life, which would correct the miseries and woes of this.

The new exposition I found in this Ragged School, of the frightful neglect by the State of those whom it punishes so constantly, and whom it might, as easily and less expensively, instruct and save; together with the sight I had seen there, in the heart of London; haunted me, and finally impelled me to an endeavour to bring these Institutions under the notice of the Government; with some faint hope that the vastness of the question would supersede the Theology of the schools, and that the Bench of Bishops might adjust the latter question, after some small grant had been conceded. I made the attempt; and have heard no more of the subject, from that hour.

On this day in 1862 Maud Arncliffe Sennett was born. Maud Sparagnapane, the elder daughter of Gaudente Sparagnapane, an Italian immigrant wholesale confectioner, and his wife, Aurelia Williams, was born on 4th February 1862. According to Elizabeth Crawford: "Nothing is known of her education. Of striking, dark appearance, she became an actress, using the stage name Mary Kingsley. She played at theatres throughout England and Scotland and, for a year, in Australia."

On 9th July 1898 she married Henry Robert Arncliffe Sennett, who took over the family business in Clerkenwell, Gaudente Sparagnapane and Company, that boasted that it was the country's "Oldest Established Manufacturers of Christmas Crackers and Wedding Cake Ornaments".

In January 1906 Maud Arncliffe Sennett read a letter from Millicent Fawcett about women's suffrage in The Times. As a result she joined the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon after she became a member of the Hampstead branch of the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU). According to her biographer "her experience as an actress made her a most effective speaker".

In June 1908 Sennett resigned from the WSPU. She now joined the Women's Freedom League and later became a member of its national executive. In her autobiography she commented on the WFL's two leaders, Teresa Billington-Greig and Charlotte Despard: "Billington-Greig was brilliant, but, I think, weak secretary who held the fort for the absent leader and kept grip of the machine. Mrs Despard, the popular reformer, did not organise; she was president and a sort of flaming torch that toured London and the country." Maud Arncliffe Sennett resigned from the WFL in July 1910.

Sennett was also active in the the Actresses' Franchise League. In her autobiography she claims that "there was more peace and harmony among these gracious women, and more generosity of mind and less jealousy than one had seen in the other groups." She also gave donations to the Men's League For Women's Suffrage.

In November 1911 she was arrested for breaking a window in the office of The Daily Mail. In court she explained it was a protest against the paper's policy of ignoring the fund-raising success of the WSPU. She added: "I broke the windows of the Daily Mail as a protest against the corruption of the Press for withholding, with malice aforethought, the truth about the suffrage movement from the great British public. I am an employee of male labour, and the men who earn their living through the power of my poor brain, the men whose children I pay to educate, whose members of Parliament I pay for, and to whose old-age pensions I contribute - these are allowed a vote, while I am voteless." Her subsequent fine was paid by Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the newspaper.

Despite no longer being a member, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, continued to give money to the Women Social & Political Union until it started its arson campaign. In June 1913 she also gave £100 to The Daily Herald. Later that month she resigned from the Actresses' Franchise League. In 1914 she joined the United Suffragists.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Maud Arncliffe Sennett disagreed with this strategy and continued to campaign for women's suffrage, through the Women's Freedom League and the United Suffragists. She also provided financial support to Sylvia Pankhurst and the East London Federation of Suffragettes.

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918.

Maud Arncliffe Sennett died from tuberculosis on 15th September 1936 at her home, Eversheds, Midhurst. Her husband then arranged the publication of her autobiography and gave to the British Museum the scrapbooks she had compiled during the suffrage campaign.

On this day in 1868 Constance Gore-Booth (Constance Markievicz), the third child of Sir Henry Gore-Booth, was born on 4th February, 1868. Her sister was Eva Gore-Booth. She lived at Lissadell House in County Sligo. Her biographer, has pointed out: "Taking advantage of the family's extensive grounds Constance Gore-Booth enjoyed country pursuits, including hunting, driving, and riding, and became especially well known for her skill with the rifle and in the saddle. With Eva she was educated by governesses at home, her tutelage consisting mainly of instruction in the genteel arts of poetry, music, and art appreciation."

In 1886 she made a grand tour of the continent, and in the following year was presented to Queen Victoria. Her father, Sir Henry Gore-Booth, always attempted to act as a good landlord and provided free food for his tenants during the 1879-80 famine. It was probably the example of Gore-Booth that help develop in his two daughters, Constance and Eva Gore-Booth, a deep concern for the poor.

In 1893 Constance moved to London to study art at the Slade. It was at this time that she joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Later she moved to France where she continued her studies at the Julian School in Paris. In 1896 she joined with Eva Gore-Booth, to establish the Sligo Women's Suffrage Association.

While in France Constance met and married Count Casimir Markiewicz, a Polish-Russian nobleman. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "Like Constance Markiewicz he had thrown over the life allotted to him - in his case the study of law in Kiev - to travel to Paris and become an artist. Despite these seemingly good portents her announcement in early 1900 that she intended to marry Casi caused a certain amount of consternation."

They married in 1900 and and their daughter, Maeve, was born the following year. The couple moved to Paris in 1902 and their daughter was left in the care of Lady Gore-Booth. They returned to Dublin and Constance developed a reputation as a talented landscape artist. She also acted in several plays at the Abbey Theatre and joined Maud Gonne as a member of revolutionary group, the Daughters of Ireland.

Constance Markiewicz continued to be interested in the struggle for women's rights. In one speech she said: "We are told the principal argument against our having votes is that we don't make noise enough. Of course it is an excellent thing to be able to make a good deal of noise, but not having done so seems hardly a good enough reason for refusing the franchise." In 1908 she joined Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, May Billinghurst, Annie Kenney and Adela Pankhurst in the campaign against Winston Churchill in the parliamentary election in Manchester North West.

In 1908 Constance became a member of Sinn Fein, an organization formed by Arthur Griffith six years earlier. The following year she founded Fianna Eireann, the youth movement of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. In 1911 Constance Markiewicz was arrested with Helena Moloney when they took part in a demonstration against the visit of George V to Ireland.

Constance Markiewicz joined James Connolly , James Larkin and Maud Gonne in the campaign to force the authorities to extend the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act to Ireland. She also started a scheme to feed poor children in Dublin and provided a soup kitchen in Liberty Hall during the lockout of unionized workers in 1913. Later that year she was elected Honorary treasurer to the Irish Citizen Army.

During the Easter Rising in April 1916, Constance Markiewicz was appointed second in command to Michael Mallin in St Stephen's Green. After a week of intense fighting Markievicz and her fellow rebels surrendered. After her arrest was charged with treason and sentenced to death. Her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, organised the successful campaign against her death sentence. It was eventually commuted to penal servitude for life because the authorities were unwilling to execute a woman. She was almost the only leader of the uprising to have survived.

Constance Markiewicz served fourteen months of her sentence at Aylesbury Prison before being released in the general amnesty of June 1917. She was immediately elected to the executive of Sinn Fein. Soon afterwards she was imprisoned again for her part in the campaign against the conscription of Irish men into the British Army.

After the passing of the passing of the Qualification of Women Act, Constance, while in prison, stood as the Sinn Fein candidate for the St. Patrick's division of Dublin. She was the only woman who was successful in the 1918 General Election. However, like the seventy two Sinn Fein MPs, she did not attend the House of Commons in London.

Released from prison in March 1919 she was appointed secretary for labour in the first Dáil Éireann. She was arrested again in June for making a seditious speech, and was sentenced to four months' hard labour - her third prison term in four years. After another arrest a sentence of two years' hard labour in the following year was interrupted by the general amnesty that followed the signing of the Irish Peace Treaty.

Constance Markiewicz was elected to the Irish Free State parliament in August 1923. She was arrested for the last time in November 1923 but was released soon after she went on hunger strike in protest. She joined Fianna Fáil on its establishment in 1926 and stood successfully as a candidate for the new party in the general election of 1927.

Her biographer, Anne Marreco, commented: "The young intellectual republicans who met her during these last years of her life found it hard to penetrate the mask of tense exhaustion, the gum-chewing, the chain-smoking, the shabby clothes, in order to perceive the exceptional being that still lay behind the ruins of her beauty and her physical elan."

Constance Markiewicz died of peritonitis at Sir Patrick Dun's Hospital in Dublin on 15th July 1927 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in the city.

On this day in 1869 William Dudley Haywood, the son of a South African woman and a Kentucky miner, was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. When he was a young boy he lost an eye in an accident. His parents were poor and at the age of nine he began work down a mine in Winnemucca, Nevada. While working as a miner Haywood met Patrick Reynolds, a member of the Knights of Labor. Reynolds was to have a lasting influence on Haywood's political views.

Haywood married Jane Minor, the daughter of a rancher, and for a whilhad a homestead in Idaho. His wife suffered from poor health and the venture was not successful. In 1896 Haywood found work in the Blaine mine in Silver City, and soon afterwards joined the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Haywood became active in the union campaigns to increase wages and to bring an end to child labour in the mines. According to his biographer, Joseph R. Conlin: "He was an excellent administrator, maintaining virtually total organizational control of the town, supervising the hospital, and negotiating peacefully with employers.... Over six feet tall, well over two hundred pounds, and with a glowering glass eye, Haywood soon earned a reputation as a resolute crisis leader."

In 1901 Haywood was elected secretary-treasurer of the WFM. Later that year he joined the American Socialist Party. In 1901 Haywood was elected secretary-treasurer of the WFM. Later that year he joined the American Socialist Party. Haywood also edited the Miners' Magazine, the journal of the WFM, and he used this position to promote the idea of socialism and argued that America should become a cooperative commonwealth. Other trade union leaders such as Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon were also converted to socialism.

Haywood and his political friends were unhappy with the conservative approach of the American Federation of Labour and on 27th June, 1905, they held a meeting in Chicago. Those who attended the meeting included Eugene V. Debs, Daniel De Leon, Mother Jones, Lucy Parsons and Charles Moyer. At the convention it was decided to form the radical labour organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

In 1905 representatives of 43 groups who opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour, formed the radical labour organisation, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). At first its three main leaders were William Haywood, Daniel De Leon and Eugene V. Debs. Other important figures in the movement included Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Mary 'Mother' Jones, Lucy Parsons, Hubert Harrison, Carlo Tresca, Joseph Ettor, Arturo Giovannitti, William Z. Foster, Eugene Dennis, Joe Haaglund Hill, Tom Mooney, Floyd B. Olson, James Larkin, James Connolly, Frank Little and Ralph Chaplin.

In 1905 Haywood was charged with taking part in the murder of Frank R. Steunenberg, the former governor of Idaho. Steunenberg was much hated by the trade union movement after using federal troops to help break strikes during his period of office. Over a thousand trade unionists and their supporters were rounded up and kept in stockades without trial.

James McParland, from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was called in to investigate the murder. McParland was convinced from the beginning that the leaders of the Western Federation of Miners had arranged the killing of Steunenberg. McParland arrested Harry Orchard, a stranger who had been staying at a local hotel. In his room they found dynamite and some wire.

McParland helped Orchard to write a confession that he had been a contract killer for the WFM, assuring him this would help him get a reduced sentence for the crime. In his statement, Orchard named Hayward and Charles Moyer (president of WFM). He also claimed that a union member from Caldwell, George Pettibone, had also been involved in the plot. These three men were arrested and were charged with the murder of Steunenberg.

Charles Darrow, a man who specialized in defending trade union leaders, was employed to defend Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone. The trial took place in Boise, the state capital. It emerged that Harry Orchard already had a motive for killing Steunenberg, blaming the governor of Idaho, for destroying his chances of making a fortune from a business he had started in the mining industry. During the three month trial, the prosecutor was unable to present any information against Hayward, Moyer and Pettibone except for the testimony of Orchard and were all acquitted.

In 1908 the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) split into two factions. The group headed by Eugene V. Debs advocated political action through the Socialist Party and the trade union movement, to attain its goals. The other faction, led by Haywood, believed that general strikes, boycotts and even sabotage were justified in order to achieve its objectives. Haywood's views prevailed and Debs, and others who thought like him, left the organisation.

George Seldes interviewed Haywood and Joe Hill in 1912: "When Bill Hayward came to the coal and iron capital of America, Ray Springle and I went to his headquarters, not for news stories, which we knew would never be published, but out of interest in the new labor movement, the Industrial Workers of the World. And so, by chance along with its new leaders we met the ballad-maker of the IWW, Joe Hill."

Ramsay MacDonald saw Haywood make a speech during this period: "William Haywood is the embodiment of the Sorel philosophy, roughened by the American industrial and civic climate, a bundle of primitive instincts, a master of direct statement. He is useless on committee; he is a torch amongst a crowd of uncritical and credulous workmen. I saw him at Copenhagen, amidst the leaders of the working-class movements drawn from the whole world, and there he was dumb and unnoticed; I saw him addressing a crowd in England, and there his crude appeals moved his listeners to wild applause. He made them see things, and their hearts bounded up to be up and doing."

Haywood remained active in the Socialist Party and was seen as the leader of the radical left. Eventually, in 1912 Victor Berger and Morris Hillquit, the leaders of the right-wing, gained control and expelled Haywood and his followers. As Joseph R. Conlin explains: "They disapproved of his militant rhetoric on behalf of sabotage, which they interpreted as meaning violence, and by his disdain for the electoral approach to socialism."

In January 1912 the America Woolen Company reduced the wages of its workers. This caused a walk-out and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), who had been busy recruiting workers into the union, took control of the dispute. The IWW formed a strike committee with two representatives from each of the nationalities in the industry. It was decided to demand a 15 per cent increase in wages, double-time for overtime work and a 55 hour week.

Haywood, Carlo Tresca and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn now arrived in Lawrence and took over the running of the strike. On 12th March, 1912, the America Woolen Company acceded to all the strikers' demands. By the end of the month, the rest of the other textile companies in Lawrence also agreed to pay the higher wages.

In 1913 Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World helped organize the silk workers at the Paterson Silk Mills. During the dispute over 3,000 pickets were arrested, most of them received a 10 day sentence in local jails. Two workers were killed by private detectives hired by the mill workers. These men were arrested but were never brought to trial. However, the strike fund was unable to raise enough money and in July, 1913, the workers were starved into submission.

Haywood replaced Vincent St. John as secretary-treasurer of the IWW in 1913. By this time, the IWW had 100,000 members. In 1914, one of the leaders of the IWW, Joe Haaglund Hill was accused of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman. Convicted on circumstantial evidence and despite of mass protests, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915. Whereas another IWW leader, Frank Little, was lynched in Butte, Montana.

Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World opposed the United States becoming involved in the First World War. He issued a statement on behalf of the IWW: "With the European war for conquest and exploitation raging and destroying the lives, class consciousness and unity of the workers, clouding the main issues, we openly declare ourselves the determined opponents of all nationalistic sectionalism, or patriotism, and the militarism preached and supported by our one enemy, the capitalist class. We condemn all wars, and for the prevention of such, we proclaim the anti-militarist propaganda in time of peace and, in time of war, the General Strike in all industries."

William Haywood did not agitate against it nor forbid members to comply with the draft. Nevertheless, politicians and employers' associations attacked the IWW as disloyal and dangerous. In a series of raids resulted in the indictment of Haywood and most of the union's leadership under the Espionage Act. After a long trial in Chicago, Haywood was sentenced to a fine of $20,000 and twenty years' imprisonment.

In March 1921, Haywood jumped bail and fled to the Soviet Union, while most of his co-defendants languished in prison. As Joseph R. Conlin has pointed out: "IWW morale was shattered. Although individuals remembered him affectionally and excused his action without justifying it, his influence on the American Left had all but vanished."

The Russian government placed Haywood in charge of the Kuzbas coal-mining colony. He occasionally visited Walter Duranty, who worked for the New York Times and was based in Moscow. Haywood told Duranty: "The trouble with us old Wobblies is that we all know how to sock scabs and mine-guards and policemen or make tough fighting speeches to a crowd of strikers but we aren't so long on this ideological theory stuff as the Russians." Haywood predicted that the Soviet leadership would eventually split over these issues. "There's something in that but it goes far deeper. These Russians attach the hell of a lot to ideological theory, and mark my words, if they're not careful they'll come to blows about it one of these days. Don't you know yet that most of them would sooner talk than work, or even eat?"

Haywood also became friendly with another journalist, Eugene Lyons. In his book, Assignment in Utopia (1937), he wrote: "Though stupidly regarded by so many as un-American, Haywood's every nerve and muscle was rooted in the American soil, and the movement which he started and led - a movement of hoboes, drifters, unskilled workers, lumberjacks and miners - was likewise authentically American in a sense that made it incomprehensible to foreign students. He had fled to Russia with other IWW men while out on bail and was therefore forever cut off from his native land. This robust, two-fisted American, essentially democratic and idealistic in his instincts, found the Bolshevik system of impersonal brutality hateful and fumed inwardly because he could say and do nothing about it. After a lifetime of fighting what he considered the delusions of political action, he could not swallow a super-state, whatever slogans it might profess. He was suddenly an impotent alien, dependent on the bounty of a dictatorial state, and unable to return home. Out of one prison he had escaped into another. He was a pathetic ruin. The solace of his last years was a Russian wife much younger than himself, who nursed him and coddled him with great devotion. It was her firm hand which kept him from drink and imposed absolute rest and thus prolonged his life."

William Haywood was in poor health and died in the Soviet Union on 18th May, 1928. His autobiography, Bill Haywood's Book (1929) was published after his death.

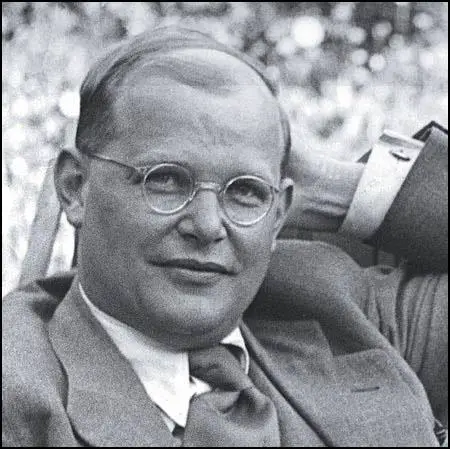

On this day in 1906 Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the son of the psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer, and brother of Klaus Bonhoeffer, was born Breslau, Germany, on 4th February, 1906. He went to the Grunewald Gymnasium in Berlin where he became friends with Hans Dohnányi. He studied theology in Tubingen and in 1927 published Sanctorum Communio. In 1930 he went to New York to study at the Union Theological Seminary.

On his return to Germany he published Act and Being (1931) and became a lecturer in theological. As he was a strong opponent of fascism he decided to leave Germany when Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933 and found work as a pastor in London.

When he heard that Martin Niemöller and Karl Barth had formed the anti-Nazi Confessional Church, Bonhoeffer decided to return and join the struggle. He wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr: "I must live through this difficult period of our national history with the Christian people of Germany…. Christians in Germany are going to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive, or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying our civilization. I know which of these alternatives I must choose."

Elisabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern have argued: "Seeing that the Nazis intended to impose their dogma - that race, not religion, determined one’s civic identity - on the churches, Bonhoeffer joined other pastors in challenging the conservative-reactionary church leaders who acceded to this view. The dissidents organized themselves into what became known as the Confessing Church, which more than two thousand pastors joined, and Bonhoeffer alerted ecumenical organizations abroad to the Nazi threats. In 1935, he readily accepted a teaching position at a remote Pomeranian estate in a quasi-legitimate “preachers’ seminary.” He spent three years there, but went often to Berlin to see his parents - and to talk to his brother-in-law Hans, who was fighting the Nazis on different fronts." By 1937 over 800 pastors had been arrested. Bonhoeffer was banned from public meetings in Berlin, but he continued to teach and guide his students in Pomerania.

In 1938 Hans Dohnányi introduced Bonhoeffer to Wilhelm Canaris, the head of Abwehr, and Hans Oster his Chief of Staff. Both men were involved in an anti-Nazi conspiracy. Bonhoeffer was recruited as a double agent. As Alan Bullock has pointed out: "The Abwehr provided admirable cover and unique facilities for a conspiracy." On 19th March, 1939, Canaris sent him to London to meet with Bishop George Bell. The next month he went on a mission to the United States. On a visit to Sweden in 1942, Bonhoeffer visited Sweden and passed on proposals from the conspirators for peace terms with the Allies. According to Louis L. Snyder: "He helped seven Jews to escape to Switzerland, an operation that nearly cost him his life... All those who came into contact with him were impressed by his noble bearing and cheerfulness under painful conditions."

In early 1943 a group of anti-Nazis that included Bonhoeffer, Wilhelm Canaris, Friedrich Olbricht, Henning von Tresckow, Friedrich Olbricht, Werner von Haeften, Claus von Stauffenberg, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Hans Dohnányi, Erwin Rommel, Franz Halder, Klaus Bonhoeffer, Hans Gisevius, Fabian Schlabrendorff, Ludwig Beck and Erwin von Witzleben met to discuss what action they should take. Initially the group was divided over the issue of Hitler. Gisevius and a small group of predominantly younger conspirators felt that he should be killed immediately. Canaris, Witzleben, Beck, Rommel and most of the other conspirators believed that Hitler should be arrested and put on trial. By using the legal system to expose the crimes of the regime, they hoped to avoid making a martyr of Hitler. Oster and Dohnanyi argued that after Hitler was arrested he should be brought before a panel of physicians chaired by Dohnanyi's father-in-law, the psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer, and declared mentally ill.

On 5th April 1943, Schutzstaffel (SS) officers entered the Abwehr building in Berlin. Wilhelm Canaris was told that they had received information that Hans Dohnányi had been taking bribes for smuggling Jews into Switzerland. After carrying out a search of the premises Dohnányi was arrested. Later that day Dohnányi's wife and several of his friends, including Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Klaus Bonhoeffer, were also taken into custody. Dohnányi managed to send out a message to General Ludwig Beck asking him to destroy his records of the conspiracy. However, Beck insisted that they be preserved for historical evidence of what Good Germans had done to fight Nazism.

Dohnányi's archives were found by the Gestapo on 22nd January 1944. This led to the arrest of other conspirators, including Arthur Nebe. Although clearly guilty of treason, Dohnányi was kept alive in an attempt to discover the full extent of the conspiracy against Adolf Hitler. In June 1944 he smuggled out a message to Otto John: "Not one of us really knows how long he can resist torture once they start doing their worst." Dohnányi arranged for his wife to smuggle him a dysentery culture. This produced a grave case of the disease that provided periodic relief from the ordeal of interrogation.

Bonhoeffer was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. On 4th April 1945 the Gestapo discovered the secret diaries of Wilhelm Canaris. Hitler now gave orders for the conspirators to be executed. This information was used in the trial of Bonhoeffer, Canaris, Hans Dohnányi, Hans Oster, Ludwig Gehre and Karl Sack. Oster appeared first and having abandoned hope, admitted everything. Canaris also confessed and the others followed. That evening the court pronounced the death sentence on all the men. That evening Canaris tapped out a final message to the prisoner in the next cell, a Danish secret service officer: "My days are done. Was not a traitor."

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was hanged at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp on 9th April 1945. Elisabeth Sifton and Fritz Stern have suggested: "One truth we can affirm: Hitler had no greater, more courageous, and more admirable enemies than Hans von Dohnányi and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Both men and those closest to them deserve to be remembered and honored. Dohnányi summed up their work and spirit with apt simplicity when he said that they were 'on the path that a decent person inevitably takes.' So few traveled that path - anywhere." Bonhoeffer's books, Ethics (1949) and Letters from Prison (1953) were published posthumously.

On this day in 1908 Julian Heward Bell, the son of Clive Heward Bell (1881–1964) and Vanessa Bell, the sister of Virginia Woolf, was born at 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, London. He spent most of his childhood at the family home of Charleston, Sussex.

Bell was educated at Leighton Park School, a Quaker institution, and at King's College, Cambridge (1927–34). While at university, he contributed to The Venture, and was a member of the Cambridge Apostles. Other members of this group included John Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, G.E. Moore and Rupert Brooke. Dr. Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit met Bell when he was at university. "Julian had asked me if I had been one of the elect, but my exclusion did not stop us having many very Apostolic discussions."

His first book of poems, Winter Movement (1930), sold poorly but received some good reviews. Bell's poem, Arms and the Man, appeared alongside those of William Empson, W. H. Auden, and Stephen Spender in New Signatures (1932). Bell, who was a socialist, was critical of the communism of Auden and Spender. He once wrote that "we are all Marxists now" but considered it a "dismal religion".

In 1935 Bell accepted the position of professor of English at the University of Wuhan in China. The following year Bell published his book of poems, Works for Winter. He also wrote an introduction to the anti-war book, We Did Not Fight: 1914-18 (1935). The book included contributions from Siegfried Sassoon, Richard Sheppard, Bertrand Russell, Norman Angell, Harry Pollitt and James Maxton.

In an article in the Times Literary Supplement he explained his political views: "Like nearly all the intellectuals of this generation, we are fundamentally political in thought and action: this more than anything else marks the difference between us and our elders. Being socialist for us means being rationalist, common-sense, empirical; means a very firm extrovert, practical, commonplace sense of exterior reality."

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Bell decided that he must contribute to the war against fascism. His parents, Clive Bell and Vanessa Bell, tried to persuade him not to go. So did his friends. David Garnett later recalled how he went to Charleston "to try to persuade him that he would be far better employed in helping to prepare for inevitable war against Hitler than in risking his life in Spain where he could take no effective or important part." Virginia Woolf arranged for Bell to meet Kingsley Martin and Stephen Spender, as they both had unpleasant experiences in Spain during the early stages of the war.

E. M. Forster also tried to convince him that it would be an immoral act to take part in a war. Bell defended his decision by claiming that he was no longer a pacifist. However, after pleading from his mother, he agreed that he would go to Spain, not as a soldier in the International Brigades but as an ambulance driver with the British Medical Aid Unit.

Bell left for Spain on 6th June 1937. Dr. Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit, who was head of the unit, later wrote: "Though Julian had great worldly experience, he had retained a capacity for wonder, an innocence, a candour, and a ceaseless zest for activity. All this made him magically attractive. Though he detested the heartless destruction of war, it did not make him afraid. He was consistently courageous."

Julian Bell worked under Richard Rees who had joined as an ambulance driver soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. He wrote to Vanessa Bell on 1st July that he and Rees had been "evacuating badly wounded patients to a rear hospital about a hundred miles off." He added: "I do think I'm being of real use as a driver, in that I'm careful and responsible and work on my car - a Chevrolet ambulance... Most of our drivers are wreckers, neglect all sorts of precautions like oiling and greasing, over speed etc."

Bell also told his mother that: "There is a sudden crisis here - at last - and rumours of an attack." This was the offensive at Brunete. The Popular Front government launched a major offensive on 6th July in an attempt to relieve the threat to Madrid. General Vicente Rojo sent the International Brigades to Brunete, challenging Nationalist control of the western approaches to the capital. The 80,000 Republican soldiers made good early progress but they were brought to a halt when General Francisco Franco brought up his reserves. Fighting in hot summer weather, the Internationals suffered heavy losses.

As the authors of Journey to the Frontier (1966) have pointed out: "Julian was now as much in the thick of things as he could have hoped: at last he was having his experience of war. Admittedly he was a non-combatant, but in the Brunete campaign the ambulance driver was as exposed to danger as the soldier; the job to be done demanded strength, endurance, resourcefulness and courage. If Julian was denied the satisfaction of bearing arms, he was granted the satisfaction, denied to the ordinary soldier, of knowing that what he was doing was actually useful... At night whole square kilometres of earth would go up in flame." Ambulance drivers were only seldom able to take advantage of the "illusory safety of trenches and dug outs", and casualties among them were heavy: by the end of the three weeks' Brunete campaign, one half of the British Medical Unit had been killed."

Bell worked with, Dr. Archie Cochrane, an old friend from King's College. His fellow ambulance driver, Richard Rees, claimed that Bell "was having the most wonderful time of his life". He appeared to find the danger of his actions exciting. When his ambulance was destroyed by a bomb on 15th July, he volunteered to go to the front as a stretcher-bearer.

On the 18th July, the British Medical Unit received a replacement vehicle for Bell. Later that day he was driving his ambulance along the road outside Villanueva de la Cañada when it was hit by a bomb dropped by a Nationalist pilot. Dr. Kenneth Sinclair-Loutit recalled in his autobiography, Very Little Luggage: "It was on the 18th of July 1937 that the Luftwaffe bombed the spot where Julian was repairing the road for his Ambulance to move forward. He had a massive lung wound; his case was beyond hope but he came back in time for us to be able to make his end comfortable."

Julian Bell was taken to the military hospital at El Escorial near Madrid. Dr. Archie Cochrane was the doctor who treated him in the receiving-room. As soon as he examined him, he realized that he had been mortally wounded; a shell fragment had penetrated deep in his chest. Bell was still conscious and murmured to Cochrane: "Well, I always wanted a mistress and a chance to go to war, and now I've had both." He then fell into a coma from which he never awakened. Richard Rees saw him in the mortuary. He later recalled: "He looked very pale and clean, almost marble-like. Very calm and peaceful, almost as if he had fallen asleep when very cold."

On this day in 1913 Rosa Parks was born in Tuskegee, Alabama. When Rosa was a child her mother, Leona McCauley, separated from her husband and moved to Montgomery. McCauley was a school teacher and encouraged her daughter to be active in the struggle for civil rights. "Years later she remembered how racism permeated the details of everyday life. Black women would be served last if they tried to buy new shoes; when they tried a hat on in a store the saleswoman would put a bag inside it." (1)

In 1932 Rosa married a barber, Raymond Parks. Both were members of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and Rosa served as the secretary of the Montgomery chapter. During this period she became close friends with Philip Randolph, Edgar Nixon and Ella Baker. (2)

These activists worked within a range of different organizations. This included the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Established in 1942, by a group of students in Chicago, members were mainly pacifists who had been deeply influenced by Henry David Thoreau and the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by blacks to obtain civil rights in America. (3)

In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. CORE gave out the following instructions taking the hourney: "If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat. If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: 'As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court'. If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move. If the police asks you to 'come along,' without putting you under arrest, tell them you will not go until you are put under arrest. If the police put you under arrest, go with them peacefully. At the police station, phone the nearest headquarters of the NAACP, or one of your lawyers. They will assist you." (4)

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Joseph Felmet, Worth Randle and Homer Jack. Rustin wrote: "At times freedom will demand that its followers go into situations where even death is to be faced. Resistance on the buses would, for example, mean humiliation, mistreatment by police, arrest, and some physical violence inflicted on the participants. But if anyone at this date in history believes that the 'white problem,' which is one of privilege, can be settled without some violence, he is mistaken and fails to realize the ends to which men can be driven to hold on to what they consider their privileges. This is why Negroes and whites who participate in direct action must pledge themselves to non-violence in word and deed. For in this way alone can the inevitable violence be reduced to a minimum." (5)

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

In Montgomery, like most towns in the Deep South, buses were segregated. Rosa Parks and other civil rights activists considered using CORE tactics in Montgomery. However, under pressure from the NAACP, this never took place. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against these tactics and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

In early 1955, Claudette Colvin, a 15 year old black girl was dragged off a bus in Montgomery and arrested for not giving up her seat to a white person. The NAACP now agreed to take up the Colvin incident as a test case. It believed that this would result in a similar outcome to the 1954 Supreme Court decision on segregation in education. However, the NAACP decided to drop the idea when they discovered that Colvin was pregnant. They knew that the authorities in Montgomery would use this against them in the propaganda war that would inevitably take place during this legal battle.

On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, left Montgomery Fair, the department store where she worked, and got on the same bus as she did every night. As always she sat in the "black section" at the back of the bus. However, when the bus became full, the driver instructed Rosa to give up her seat to a white person. This had happened to Rosa several times before. In fact, the same bus driver had forced her off the bus in 1943 for committing the same offence. Once again she refused and was arrested by the police. She was found guilty of violating the segregation law and fined.

It was only at this stage, after consulting friends and family, that she decided to approach the NAACP and volunteer to become a test case. This was a brave decision as she knew it would result in persecution by the white authorities. For example, Parks was immediately sacked from her tailoring job with Montgomery Fair.

Martin Luther King, a pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, agreed to help organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that from 5th December, black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Edgar Nixon suffered the same fate. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also had to endure harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration, and the boycott came to an end on 20th December, 1956. After the success of this campaign, Parks became known as the "mother of the Civil Rights Movement".

Rosa and her family were now targets for white racists and in 1957 the family decided to move to Detroit. Later she became a special assistant to Democratic Congressman, John Conyers.

Rosa Parks remained active in the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and in 1987 she founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development, which aimed to help the young and educate them about civil rights. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) also established an annual Rosa Parks Freedom Award. Her autobiography, Rosa Parks: My Story, was published in 1992. Rosa Parks died on 24th October, 2005.

On this day in 1924 Helena Normanton becomes the first female counsel to represent a client at the Old Bailey. The following year she became the first woman to conduct a case in the United States, that established American women's right to retain their maiden names. Despite these achievements her earning from legal work was so low she had to supplement her income by renting rooms in her house in Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury. She also published two books on famous criminal cases, The Trial of Norman Thorne (1929) and The Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse (1931).

Helena Normanton campaigned for changes in matrimonial law. At the annual meeting of the National Council of Women in October 1934, her proposals were strongly attacked by the Mothers' Union. In 1938 Normanton was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Edith Summerskill and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

Helena Wojtczak remarked in Notable Sussex Women (2008): "In 1948 she became the first woman to lead the prosecution in a murder trial, and the following year became one of the first two women to be appointed King's Counsel. She was an excellent public speaker, wrote articles for various publications and books on a wide variety of subjects, from Shakespeare to buying a house."

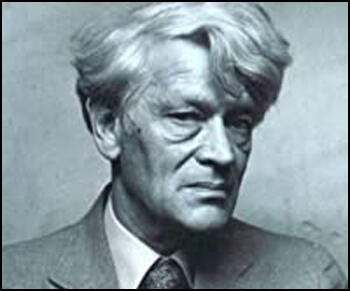

On this day in 1979 E. P. Thompson published an article on Marxism in the The Observer: "Anyone who is even casually informed knows that Marxism, as an intellectual system, is in a state of crisis. The term 'Marxism' conceals an immense conflict going on between different claimants to the Marxist tradition. In Russia dissidents like Roy Medvedev are offering, in Marxist terms, scholarly exposures of the Stalin era - analyses which are refused publication by Soviet (Marxist-Leninist) publishing houses. In East Germany Rudolf Bahro, a Marxist, is imprisoned by a Marxist state for his stubborn and honest thought. If we move from intellectual to political and social movements, the conflict is even more obvious. In Africa the most disparate regimes, from old-fashioned military tyrannies to more open societies with real democratic potential, all invoke the word 'Marxist'. As a Marxist (or a Marxist-fragment) in the Labour Party, I have always tried to envisage a politics that will enable us, in this country, to effect a transition to a socialist society - and a society a great deal more democratic, in work as well as in government, than our present one - without rupturing the humane and tolerant disposition for which our working class has often been distinguished, in this country, if not abroad."

On this day in 1980 Edith Summerskill died at her home in Millfield Lane, Highgate.

Edith Summerskill, the youngest daughter of Dr William Summerskill (1866–1947) and his wife, Edith Clara Wilde, was born in Doughty Street, London, on 19th April 1901. As a child she accompanied her father on home visits and he told her about the connections between poverty and ill-health. Dr. Summerskill held left-wing political views and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

Edith was educated at Eltham Hill Grammar School and in 1918 won a place at King's College, where she studied medicine. Trained at Charing Cross Hospital she qualified as a doctor in 1924. The following year she married Dr. Edward Jeffrey Samuel (1895–1983).

In 1928 Edith and her husband established a joint medical practice in North London. In an interview she gave to BBC Radio 4 many years later, she recalled attending her first confinement as a newly qualified doctor. Shocked at the state of the home and the undernourishment of the mother, whose first child had rickets, she said "In that room that night, I became a socialist".

In 1930 Dr Charles Brook met Dr Ewald Fabian, the editor of Der Sozialistische Arzt and the head of Verbandes Sozialistischer Aerzte in Germany. Fabian said he was surprised that Britain did not have an organisation that represented socialists in the medical profession. Brook responded by arranging a meeting to take place on 21st September 1930 at the National Labour Club. As a result it was decided to form the Socialist Medical Association. Brook was appointed as Secretary of the SMA and Somerville Hastings, the Labour MP for Reading, became the first President. Other early members included Edith Summerskill, Hyacinth Morgan, Reginald Saxton, Alex Tudor-Hart, Archie Cochrane, Christopher Addison, John Baird, Alfred Salter, Barnett Stross, Robert Forgan and Richard Doll.

The Socialist Medical Association agreed a constitution in November 1930, "incorporating the basic aims of a socialised medical service, free and open to all, and the promotion of a high standard of health for the people of Britain". The SMA also committed itself to the dissemination of socialism within the medical profession. The SMA was open to all doctors and members of allied professions, such as dentists, nurses and pharmacists, who were socialists and subscribed to its aims. International links were established through the International Socialist Medical Association, based in Prague, an organisation that had been established by Dr Ewald Fabian.

In 1931 the SMA, after representations from Somerville Hastings and Charles Brook, became affiliated to the Labour Party. The following year, at its annual party conference, a resolution calling for a national health service to be an immediate priority of a Labour government was passed. The SMA also launched The Socialist Doctor journal in 1932. Summerskill was an active member of the SMA and as John Stewart, the author of The Battle for Health: A Political History of the Socialist Medical Association (1999), has pointed out, "she put forward the case for a socialized health service, and it was she who came up with the idea of organizing social events both to raise money and to attract publicity to the organization."

Edith Summerskill, who was on the left-wing of the Labour Party, played an active role in supporting the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. On 8th August 1936 it was decided to form a Spanish Medical Aid Committee. Dr. Christopher Addison was elected President and the Marchioness of Huntingdon agreed to become treasurer. Other supporters included Summerskill, Somerville Hastings, Charles Brook, Isabel Brown, Leah Manning, George Jeger, Philip D'Arcy Hart, Frederick Le Gros Clark, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, George Lansbury, Victor Gollancz, D. N. Pritt, Archibald Sinclair, Rebecca West, William Temple, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Eleanor Rathbone, Julian Huxley, Harry Pollitt and Mary Redfern Davies. Summerskill was also involved in establishing The National Women's Appeal for Food for Spain.

John Stewart pointed out in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography that: "As a feminist, Summerskill paid particular attention to women's social and political issues. In the 1930s she was outspoken in her attacks on the prevailing high rate of maternal mortality and urged that the interests of the expectant mother must always be prioritized by the maternity services. She was especially critical of negligent doctors and inadequate provision, pointing out that a significant proportion of deaths in childbirth resulted from preventable, and hence unnecessary, infections. Unsurprisingly, this was related to broader claims for a publicly funded and administered health care service."

Summerskill was selected as the parliamentary candidate for Bury. In the 1935 General Election she was attacked by the Roman Catholic Church for her support for women's right to birth control. This contributed to her defeat and the following year she was was adopted as Labour Party candidate for the parliamentary constituency of Fulham West. Summerskill won the seat at a by-election in April 1938 and she now joined two other members of the SMA, Alfred Salter and Somerville Hastings, in the House of Commons. Later that year Summerskill was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Helena Normanton and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

During the Second World War the influence of Summerskill and the Socialist Medical Association increased. In October 1940, at the beginning of the Blitz, she told fellow MPs that the wartime organization of health services, and the impact of the war itself, had greatly and irreversibly changed the provision and perception of health care. Along with Somerville Hastings she was a member of Labour's advisory committee on public health, a body charged with formulating proposals for a national health service. In 1944 she became a member of Labour's national executive.

Summerskill was returned to the House of Commons at the 1945 General Election as MP for Fulham West. She was one of twelve SMA members elected and their was now a concerted effort to persuade the government to introduce a National Health Service. Hastings was considered too old to become Minister of Health but it was hoped that Clement Attlee would appoint another SMA member such as Edith Summerskill. However, Attlee rejected this advice and Aneurin Bevan was appointed instead.

Summerskill was appointed as parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Food. As John Stewart has pointed out: "This was always going to be a challenging position at a time of rationing and austerity - aspects of post-war life with which the British people were becoming increasingly disenchanted. Among her campaigns were those to make milk free from tuberculosis, an issue on which she could draw upon her medical knowledge."

In the 1950 Summerskill became minister of national insurance. However, she lost the post following Labour's defeat in the 1951 General Election. Over the next eight years she served on Labour's shadow cabinet. She was also a member of Labour's national executive and was party chairman in 1954–5. In 1956 was one of the platform speakers at Labour's famous Trafalgar Square rally against the Suez War.

In February 1961 Edith Summerskill was made a life peeress. She was an active member of the House of Lords and her successful private member's bill, became the 1964 Married Women's Property Act. She also supported the reform of the law relating to homosexuality and for the legalization of abortion and campaigned against nuclear weapons and the American intervention in Vietnam. In 1967 she published her autobiography, A Woman's World.

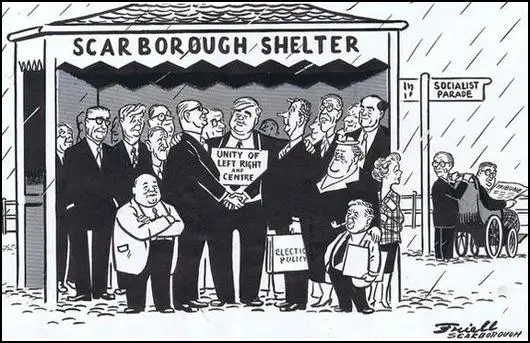

On this day in 1997 James Friell (Gabriel) died. Friell, the son of an actor, was born in Glasgow on 13th March 1912. After leaving school at fourteen, he worked in a solicitor's office and taught himself to be a cartoonist, and had his work published in the Glasgow Evening Times.

Friell studied commercial art at Glasgow School of Art in 1930 and two years later he moved to London where he found work in the advertising department of Kodak. He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and in February 1936 he joined The Daily Worker and working under the name "Gabriel" became the newspaper's political cartoonist.

During the Second World War he served in the Royal Artillery but was kept under observation as a "subversive". In 1944 he set up The Soldier magazine and worked as a cartoonist, art editor and layout man for the journal. After the war he returned to The Daily Worker.

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Harry Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive".