Suez Crisis

The Suez Canal in Egypt was opened in 1869. The shipping canal is 171 km (106 miles) long and connects the Mediterranean at Port Said with the Red Sea. It gave vessels a direct route between the North Atlantic and northern Indian oceans via the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, avoiding the South Atlantic and southern Indian oceans and reducing the journey distance from the Arabian Sea to London by approximately 8,900 kilometres (5,500 miles). A substantial shareholding (172,602 shares) was purchased by the British government in 1875. However, French shareholders still held the majority of shares. (1)

In 1882 the British Army occupied Egypt in order to protect the Suez Canal. They remained in Egypt and the British government installed a Counsul-General to rule the country. On the outbreak of the Second World War the British had 36,000 troops guarding the canal and the Arabian oil fields. (2)

Gamal Abdel Nasser

In 1952 General Mohammed Neguib and Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser forced Farouk I to abdicate. After the Egyptian Revolution Neguib became commander-in-chief, prime minister and president of the republic whereas Nasser held the post of Minister of the Interior.In April 1954 Nasser replaced Neguib as prime minister. Seven months later he also became president of Egypt. Over the next few months Nasser made it clear he was in favour of liberating Palestine from the Jews. He also began buying fighter aircraft, bombers and tanks from the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. (3)

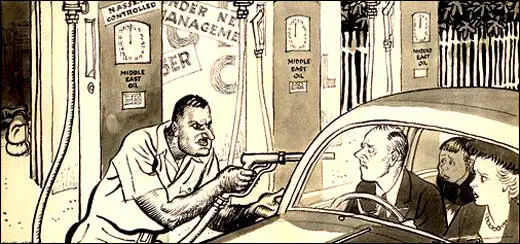

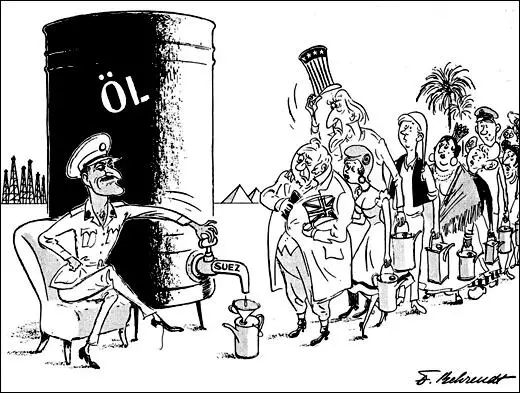

Gamal Abdel Nasser redistributed land in Egypt and began plans to industrialize the country. He also began the building of the Aswan Dam. Nasser was convinced that this would extend arable lands in Egypt and would help the industrialization process. He also advocated Arab independence and reminded the British government that the agreement allowing to keep soldiers at Suez expired in 1956. (4)

President Dwight Eisenhower became concerned about the close relationship developing between Egypt and the Soviet Union. In July 1956, Eisenhower cancelled a promised grant of 56 million dollars towards the building of the Aswan Dam. Nasser was furious and on 26th July he announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam. (5)

Prime Minister Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden replaced Winston Churchill as prime minister in April, 1955. Eden believed that he should take an early opportunity of seeking a fresh mandate from the electorate, and nine days after becoming prime minister he announced a general election for 26th May. At the time the Conservative Party was only 4% ahead of the Labour Party. During the 1955 General Election Eden emphasized the theme of the "property-owning democracy", and won by sixty seats. It was the first-time since 1900 that an incumbent administration had increased its majority in the House of Commons. (6)

The Labour leader, Clement Attlee, retired and was replaced by the much younger, Hugh Gaitskell. It has been argued that when Hugh Gaitskell became leader in December, 1955, "British politics moved into a new era. Press criticisms became less inhibited. To some extent, Churchill and Attlee had been above criticism, but both Eden and, eventually, Gaitskell were fair game for a new breed of journalist." Eden found criticism difficult to take and William Clark, his press secretary, was kept very busy issuing statements defending his policies. (7)

President Dwight Eisenhower became concerned about the close relationship developing between Egypt and the Soviet Union. In July 1956 Eisenhower cancelled a promised grant of 56 million dollars towards the building of the Aswan Dam. Gamal Abdel Nasser was furious and on 26th July he announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam. (8)

Eden wrote to President Dwight Eisenhower for support: "In the light of our long friendship, I will not conceal from you that the present situation causes me the deepest concern. I was grateful to you for sending Foster over and for his help. It has enabled us to reach firm and rapid conclusions and to display to Nasser and to the world the spectacle of a united front between our two countries and the French. We have however gone to the very limits of the concessions which we can make.... I have never thought Nasser a Hitler, he has no warlike people behind him. But the parallel with Mussolini is close. Neither of us can forget the lives and treasure he cost before he was finally dealt with. The removal of Nasser and the installation in Egypt of a regime less hostile to the West, must therefore also rank high among our objectives. You know us better than anyone, and so I need not tell you that our people here are neither excited nor eager to use force. They are, however, grimly determined that Nasser shall not get away with it this time because they are convinced that if he does their existence will be at his mercy. So am I." (9)

According to Harold Wilson, a Labour Party MP, Harold Macmillan, the Foreign Secretary was the main supporter of taking action against Nasser: "Eden was at first a reluctant warrior. Macmillan was putting the heat on from the start. At a separate dinner, he and Lord Salisbury were entertaining Robert Murphy, the US Defence Secretary. Macmillan took an extremely tough line about Nasser's action, which, he later explained, was designed to stiffen the American administration. Murphy was left to draw the conclusion that Britain would certainly go to war to secure the Canal and ensure free passage for the world's ships. In the whole history of the Suez fiasco, nothing has become clearer than the effect of Macmillan's tough line with Murphy both then and throughout the following weeks, when Eden was going through the torment of preparing to use force to recapture the Canal." (10)

The Suez Canal Conspiracy

At a cabinet meeting in July the minutes recorded: "The Cabinet agreed that we should be on weak ground in basing our resistance on the narrow argument that Colonel Nasser had acted illegally. The Suez Canal Company was registered as an Egyptian company under Egyptian law; and Colonel Nasser had indicated that he intended to compensate the shareholders at ruling market prices. From a narrow legal point of view, his action amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders. Our case must be presented on wider international grounds. Our argument must be that the Canal was an important international asset and facility, and that Egypt could not be allowed to exploit it for a purely internal purpose. The Egyptians had not the technical ability to manage it effectively; and their recent behaviour gave no confidence that they would recognize their international obligations in respect of it. It was a piece of Egyptian property but an international asset of the highest importance and should be managed as an international trust. The Cabinet agreed that for these reasons every effort must be made to restore effective international control over the Canal. It was evident that the Egyptians would not yield to economic pressures alone. They must be subjected to the maximum political pressure which could only be applied by the maritime and trading nations whose interests were most directly affected. And, in the last resort, this political pressure must be backed by the threat - and, if need be, the use of force." (11)

Walter Monckton, Eden's Minister of Defence, was the only cabinet minister to oppose this policy but decided against resigning: "I have remained in the Cabinet without resignation because I have not thought it right to take a step which I was assured would bring the Government down. The view which I have always expressed has been against the armed intervention which has taken place on the grounds - (a) that we should have half our own country and 90 per cent of world opinion against us; (b) that it was difficult to justify intervention on behalf of the invader and against the country invaded; (c) that it would inflame opinion against us in the Middle East and upset the whole of the Arab world; (d) that it would jeopardise our relations with the US which were the foundation of our international and defence policy." (12)

Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party, warned Eden of the consequences of using military force: "Lest there should be any doubt in your mind about my personal attitude, let me say that I could not regard an armed attack on Egypt by ourselves and the French as justified by anything which Nasser has done so far or as consistent with the Charter of the United Nations. Nor, in my opinion, would such an attack be justified in order to impose a system of international control over the canal – desirable though this is. If, of course, the whole matter were to be taken to the United Nations and if Egypt were to be condemned by them as aggressors, then, of course, the position would be different. And if further action which amounted to obvious aggression by Egypt were taken by Nasser, then again it would be different. So far what Nasser has done amounts to a threat, a grave threat to us and to others, which certainly cannot be ignored; but it is only a threat, not in my opinion justifying retaliation by war." (13)

Eden feared that Nasser intended to form an Arab Alliance that would cut off oil supplies to Europe. Secret negotiations took place between Britain, France and Israel and it was agreed to make a joint attack on Egypt. On 29th October 1956, the Israeli Army invaded Egypt. Two days later British and French bombed Egyptian airfields. British and French troops landed at Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal on 5th November. By this time the Israelis had captured the Sinai peninsula. (14)

According to some historians, the majority of British people were on Eden's side. (15) On 10 and 11 November an opinion poll found 53% supported the war, with 32% opposed (16) The majority of Conservative constituency associations passed resolutions of support of Eden. The British historian Barry Turner wrote that: "The public reaction to press comment highlighted the divisions within the country. But there was no doubt that Eden still commanded strong support from a sizeable minority, maybe even a majority, of voters who thought that it was about time that the upset Arabs should be taught a lesson. The Observer and Guardian lost readers; so too did the News Chronicle, a liberal newspaper that was soon to fold as a result of falling circulation." (17)

Hugh Gaitskell immediately attacked the military intervention by Britain, France, and Israel, calling it "an act of disastrous folly". (18) Gaitskell accusing Eden that he had been lying to him in private. (19) Brian Brivati, the author of Hugh Gaitskell (1996) has pointed out that he argued that the government's policy had "compromised the three principles of bipartisan foreign policy: solidarity with the Commonwealth, the Anglo-American alliance, and adherence to the charter of the United Nations." (20) However, it was argued: "In doing so, however, he was exposed to the Conservative charge that he had changed his position in response to the clamour of his own party's left wing. Gaitskell was in fact consistent throughout the crisis, and spoke for an internationalist tradition that was deeply rooted in British politics. It was arguably at odds with the views of some core Labour voters, but he attracted support from sections of Liberal opinion who in other respects might have found a Labour Party based on trade unions and sentiments of class solidarity unattractive." (21)

Eden made attempts to control the way the BBC reported the Suez Crisis. William D. Clark, who resigned as Eden's press secretary at the time of the crisis, later revealled that the Manchester Guardian's anti-Suez leading articles were one of the main reasons why the Prime Minister asked for the drawing up of an instrument to bring the BBC under direct Government control. The plan was never put into operation. Eden complained that the articles were "constantly quoted on the BBC and could be heard by troops overseas." According to Clark, "the resentment of the inner Cabinet was not discussed solely on the BBC, but the BBC happened to be the news service which most easily lent itself to direct Government action.... The fact was that there was a real attempt to pervert the course of news, of ordinary understanding of events. The BBC happened to be one place where Government action could most easily take place." (22)

President Dwight Eisenhower and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, grew increasingly concerned about these developments and at the United Nations the representatives from the United States and the Soviet Union demanded a cease-fire. When it was clear the rest of the world were opposed to the attack on Egypt, and on the 7th November the governments of Britain, France and Israel agreed to withdraw. According to D. R. Thorpe: "Hostile reactions from the United States, the United Nations, and the Soviet Union, then engaged in its simultaneous invasion of Hungary, led within twenty-four hours to a humiliating ceasefire. The key factor in the decision was economic. Macmillan told the cabinet on 6 November, in terms which are now known to be disingenuous in their degree of pessimism, of the run on sterling reserves (he told the cabinet of £100 million lost reserves in the first week of November, when the true figure was £31.7 million) and American treasury pressures to end the hostilities. Faced with this information, Eden had no option but to call a halt." (23) Winston Churchill later commented on Eden's decision to invade and withdraw from Egypt: "I would never have dared, and if I had dared, I would never have dared stop". (24)

Resignation of Eden

On 20th December 1959, Eden made a statement in the House of Commons when he denied foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt. Robert Blake, the author British Prime Ministers in the Twentieth Century (1978) controversially argued that the it was acceptable for Eden to lie on this issue: "No one of sense will regard such falsehoods in a particularly serious light. The motive was the honourable one of averting further trouble in the Middle East, and this was a serious consideration for many years after the event." (25)

Gamal Abdel Nasser now blocked the Suez Canal. He also used his new status to urge Arab nations to reduce oil exports to Western Europe. As a result petrol rationing had to be introduced in several countries in Europe. Eden, who had gone to stay in the home of Ian Fleming and Ann Fleming in Jamaica, came under increasing attack in the media. When Eden returned on 14th December it was to a dispirited party. On 9th January, 1957, Eden announced his resignation as Prime Minister and as a member of the House of Commons. (26)

Primary Sources

(1) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986)

It was on 26 July that Nasser announced his 'unilateral' nationalization of the Suez Canal. Anthony Eden heard the news towards the end of a Downing Street dinner to honour King Feisal of Iraq and his premier, Nuri-es-Said. The guest list is important. In addition to Hugh Gaitskell, it included the French Ambassador, Chiefs of Staff and the US Charge d'Affaires. The guests tactfully withdrew, Nuri-es-Said not making himself any more popular in Eden's eyes by pointing to the portrait of Disraeli among the others, now numbering about fifty, of ex-Prime Ministers and saying, 'That's the old Jew who got us into all this trouble' - by borrowing the money from the House of Rothschild when he heard that the Canal was for sale.

Eden was at first a reluctant warrior. Macmillan was putting the heat on from the start. At a separate dinner, he and Lord Salisbury were entertaining Robert Murphy, the US Defence Secretary. Macmillan took an extremely tough line about Nasser's action, which, he later explained, was designed to stiffen the American administration. Murphy was left to draw the conclusion that Britain would certainly go to war to secure the Canal and ensure free passage for the world's ships. In the whole history of the Suez fiasco, nothing has become clearer than the effect of Macmillan's tough line with Murphy both then and throughout the following weeks, when Eden was going through the torment of preparing to use force to recapture the Canal.

American leaders, from President Eisenhower downwards, took Macmillan's comments as representing a decision of the British Cabinet. There is surprisingly little in Macmillan's memoirs to indicate the hard line he was taking or the continuing effect of his musings in Washington. It was not until it was becoming clear that the invasion was turning into an almost farcical failure, with Harold already the odds-on favourite for the succession to the sick and exhausted Eden, that he again assumed the statesman's mantle.

(2) Hugh Gaitskell, was at a dinner party with Anthony Eden when the news of the nationalization of the Suez Canal. His comments appeared in his diary on 26th July, 1956.

He (Eden) thought perhaps they ought to take it to the Security Council.... I said 'Supposing Nasser doesn't take any notice?' whereupon Selwyn Lloyd said 'Well, I suppose in that case the old-fashioned ultimatum will be necessary.' I said that I thought they ought to act quickly, whatever they did, and that as far as Great Britain was concerned, public opinion would almost certainly be behind them. But I also added that they must get America into line.

(3) The minutes of the cabinet meeting of the British government on 27th July, 1956.

The Cabinet agreed that we should be on weak ground in basing our resistance on the narrow argument that Colonel Nasser had acted illegally. The Suez Canal Company was registered as an Egyptian company under Egyptian law; and Colonel Nasser had indicated that he intended to compensate the shareholders at ruling market prices. From a narrow legal point of view, his action amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders. Our case must be presented on wider international grounds. Our argument must be that the Canal was an important international asset and facility, and that Egypt could not be allowed to exploit it for a purely internal purpose. The Egyptians had not the technical ability to manage it effectively; and their recent behaviour gave no confidence that they would recognize their international obligations in respect of it. It was a piece of Egyptian property but an international asset of the highest importance and should be managed as an international trust.

The Cabinet agreed that for these reasons every effort must be made to restore effective international control over the Canal. It was evident that the Egyptians would not yield to economic pressures alone. They must be subjected to the maximum political pressure which could only be applied by the maritime and trading nations whose interests were most directly affected. And, in the last resort, this political pressure must be backed by the threat - and, if need be, the use of force.

(4) Message sent by Anthony Eden to President Dwight Eisenhower on 27th July, 1956.

(1) We are all agreed that we cannot afford to allow Nasser to seize control of the Canal in this way, in defiance of international agreements. If we take a firm stand over this now, we shall have the support of all the maritime Powers. If we do not, our influence and yours throughout the Middle East will, we are convinced, be finally destroyed.

(2) The immediate threat is to the oil supplies to Western Europe, a great part of which flows through the Canal. We have reserves in the United Kingdom which would last us for six weeks; and the countries of Western Europe have stocks, rather smaller as we believe, on which they could draw for a time. We are, however, at once considering means of limiting current consumption so as to conserve our supplies. If the Canal were closed we should have to ask you to help us by reducing the amount which you draw from the pipeline terminals in the Eastern Mediterranean and possibly by sending us supplementary supplies for a time from your side of the world.

(3) It is, however, the outlook for the longer term which is more threatening. The Canal is an international asset and facility, which is vital to the free world. The maritime Powers cannot afford to allow Egypt to expropriate it and to exploit it by using the revenues for her own internal purposes irrespective of the interests of the Canal and of the Canal users. Apart from the Egyptians' complete lack of technical qualifications, their past behaviour gives no confidence that they can be trusted to manage it with any sense of international obligation. Nor are they capable of providing the capital which will soon be needed to widen and deepen it so that it may be capable of handling the increased volume of traffic which it must carry in the years to come. We should, I am convinced, take this opportunity to put its management on a firm and lasting basis as an international trust.

(4) We should not allow ourselves to become involved in legal quibbles about the rights of the Egyptian Government to nationalize what is technically an Egyptian company, or in financial arguments about their capacity to pay the compensation which they have offered. I feel sure that we should take issue with Nasser on the broader international grounds summarized in the preceding paragraph.

(5) As we see it we are unlikely to attain our objective by economic pressures alone. I gather that Egypt is not due to receive any further aid from you. No large payments from her sterling balances here are due before January. We ought in the first instance to bring the maximum political pressure to bear on Egypt. For this apart from our own action, we should invoke the support of all the interested Powers. My colleagues and I are convinced that we must be ready, in the last resort to use force to bring Nasser to his senses. For our part we are prepared to do so. I have this morning instructed our Chiefs of Staff to prepare a military plan accordingly.

(6) However, the first step must be for you and us and France to exchange views, align our policies and concert together how we can best bring the maximum pressure to bear on the Egyptian Government.

(5) President Dwight Eisenhower letter to Anthony Eden on 1st August, 1956.

From the moment that Nasser announced nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, my thoughts have been constantly with you. Grave problems are placed before both our governments, although for each of us they naturally differ in type and character. Until this morning, I was happy to feel that we were approaching decisions as to applicable procedures somewhat along parallel lines, even though there were, as would be expected, important differences as to detail. But early this morning I received the message, communicated to me through Murphy from you and Harold Macmillan, telling me on a most secret basis of your decision to employ force without delay or attempting any intermediate and less drastic steps.

We recognize the transcendent worth of the Canal to the free world and the possibility that eventually the use of force might become necessary in order to protect international rights. But we have been hopeful that through a Conference in which would be represented the signatories to the Convention of 1888, as well as other maritime nations, there would be brought about such pressures on the Egyptian Government that the efficient operation of the Canal could be assured for the future.

For my part, I cannot over-emphasize the strength of my conviction that some such method must be attempted before action such as you contemplate should be undertaken. If unfortunately the situation can finally be resolved only by drastic means, there should be no grounds for belief anywhere that corrective measures were undertaken merely to protect national or individual investors, or the legal rights of a sovereign nation were ruthlessly flouted. A conference, at the very least, should have a great education effort throughout the world. Public opinion here, and I am convinced, in most of the world, would be outraged should there be a failure to make such efforts. Moreover, initial military successes might be easy, but the eventual price might become far too heavy.

I have given you my own personal conviction, as well as that of my associates, as to the unwisdom even of contemplating the use of military force at this moment. Assuming, however, that the whole situation continued to deteriorate to the point where such action would seem the only recourse, there are certain political facts to remember. As you realize, employment of United States forces is possible only through positive action on the part of the Congress, which is now adjourned but can be reconvened on my call for special reasons. If those reasons should involve the issue of employing United States military strength abroad, there would have to be a showing that every peaceful means of resolving the difficulty had previously been exhausted. Without such a showing, there would be a reaction that could very seriously affect our peoples' feeling toward our Western Allies. I do not want to exaggerate, but I assure you that this could grow to such an intensity as to have the most far-reaching consequences.

I realize that the messages from both you and Harold stressed that the decision taken was already approved by the government and was firm and irrevocable. But I personally feel sure that the American reaction would be severe and that great areas of the world would share that reaction. On the other hand, I believe we can marshall that opinion in support of a reasonable and conciliatory, but absolutely firm, position. So I hope that you will consent to reviewing this matter once more in its broadest aspects. It is for this reason that I have asked Foster to leave this afternoon to meet with your people tomorrow in London.

I have given you here only a few highlights in the chain of reasoning that compels us to conclude that the step you contemplate should not be undertaken until every peaceful means of protecting the rights and the livelihood of great portions of the world had been thoroughly explored and exhausted. Should these means fail, and I think it is erroneous to assume in advance that they needs must fail, then world opinion would understand how earnestly all of us had attempted to be just, fair and considerate, but that we simply could not accept a situation that would in the long run prove disastrous to the prosperity and living standards of every nation whose economy depends directly or indirectly upon East-West shipping.

With warm personal regard - and with earnest assurance of my continuing respect and friendship.

(6) Anthony Eden letter of President Dwight Eisenhower on 5th August, 1956.

In the light of our long friendship, I will not conceal from you that the present situation causes me the deepest concern. I was grateful to you for sending Foster over and for his help. It has enabled us to reach firm and rapid conclusions and to display to Nasser and to the world the spectacle of a united front between our two countries and the French. We have however gone to the very limits of the concessions which we can make.

I do not think that we disagree about our primary objective. As it seems to me, this is to undo what Nasser has done and to set up an international regime for the Canal. The purpose of this regime will be to ensure the freedom and security of transit through the Canal, without discrimination, and the efficiency and economy of its operation.

But this is not all. Nasser has embarked on a course which is unpleasantly familiar. His seizure of the Canal was undoubtedly designed to impress opinion not only in Egypt but in the Arab world and in all Africa too. By this assertion of his power he seeks to further his ambitions from Morocco to the Persian Gulf....

I have never thought Nasser a Hitler, he has no warlike people behind him. But the parallel with Mussolini is close. Neither of us can forget the lives and treasure he cost before he was finally dealt with.

The removal of Nasser and the installation in Egypt of a regime less hostile to the West, must therefore also rank high among our objectives.

You know us better than anyone, and so I need not tell you that our people here are neither excited nor eager to use force. They are, however, grimly determined that Nasser shall not get away with it this time because they are convinced that if he does their existence will be at his mercy. So am I.

(7) Minutes of the British government Cabinet meeting on 25th October, 1956.

It now appeared, however, that the Israelis were, after all, advancing their military preparations with a view to making an attack upon Egypt. They evidently felt that the ambitions of Colonel Nasser's Government threatened their continued existence as an independent State and that they could not afford to wait for others to curb his expansionist policies. The Cabinet must therefore consider the situation which was likely to arise if hostilities broke out between Israel and Egypt and must judge whether it would necessitate Anglo-French intervention in this area.

The French Government were strongly of the view that intervention would be justified in order to limit the hostilities and that for this purpose it would be right to launch the military operation against Egypt which had already been mounted. Indeed, it was possible that if we declined to join them they would take military action alone or in conjunction with Israel. In these circumstances the Prime Minister suggested that, if Israel launched a full-scale military operation against Egypt, the Governments of the United Kingdom and France should at once call on both parties to stop hostilities and to withdraw their forces to a distance often miles from the Canal; and that it should at the same time be made clear that, if one or both Governments failed to undertake within twelve hours to comply with these requirements, British and French forces would intervene in order to enforce compliance. Israel might well undertake to comply with such a demand. If Egypt also complied, Colonel Nasser's prestige would be fatally undermined. If she failed to comply, there would be ample justification for Anglo-French military action against Egypt in order to safeguard the Canal.

We must face the risk that we should be accused of collusion with Israel. But this charge was liable to be brought against us in any event; for it could now be assumed that, if an Anglo-French operation were undertaken against Egypt, we should be unable to prevent the Israelis from launching a parallel attack themselves; and it was preferable that we should be seen to be holding the balance between Israel and Egypt rather than appear to be accepting Israeli co-operation in an attack on Egypt alone.

(8) Statement issued by Guy Mollet and Anthony Eden (31st October, 1956)

The Governments of the United Kingdom and France have taken note of the outbreak of hostilities between Israel and Egypt. This event threatens to disrupt the freedom of navigation through the Suez Canal on which the economic life of many nations depends. The Governments of the United Kingdom and France are resolved to do all in their power to bring about the earliest cessation of hostilities and to safeguard the free passage of the Canal.

They accordingly request the Government of Israel to stop all warlike action on land, sea and air forthwith; to withdraw all Israeli military forces to a distance of ten miles east of the Canal.

The communication has been addressed to the Government of Egypt, requesting them to cease hostilities and withdraw their forces from the neighbourhood of the Canal and to accept the temporary occupation by Anglo-French - forces of key positions at Port Said, Ismailia and Suez.

The United Kingdom and French Governments request an answer to this communication within twelve hours. If at the expiration of that period one or both Governments have not undertaken to comply with the above requirements, the United Kingdom and French forces will intervene in whatever strength may be necessary to secure compliance.

(9) Walter Monckton wrote about the Suez Crisis in his unpublished memoirs.

I was in favour of the tough line which the Prime Minister took in July when Nasser announced the nationalisation of the canal and I must say that I was not fundamentally troubled by moral considerations throughout the period for which the crisis lasted. My anxieties began when I discovered the way in which it was proposed to carry out the enterprise. I did not like the idea of allying ourselves with the French and the Jews in an attack upon Egypt because I thought from such experience and knowledge as I had of the Middle East that such alliances with these two, and particularly with the Jews, were bound to bring us into conflict with Arab and Muslim feeling

Secondly, and to an even greater extent. I disliked taking positive and warlike action against Egypt behind the back of the Americans and knowing that they would disapprove of our course of action I felt that the future of the free world depended principally upon the United States and that we should be dealing a mortal blow to confidence in our alliance with them if we deceived them in this matter.

One of the curious features of the whole affair as far as the Cabinet was concerned was that partly owing to a not unnatural habit on the Prime Minister's part of preferring to take into complete confidence, when things were moving fast, only those with whom he agreed, many of us in the Cabinet knew little of the decisive talks with the French until after they happened and sometimes not even then. A great deal of the public criticism of the conduct of the Suez affair was directed at its abandonment in mid-stream rather than at its beginning. There were some discussions, many of them at night, with Washington, and I have always thought that the decisive point was reached when Mr Macmillan was of opinion that the United States would make our financial position impossible unless we called a halt.

I ought to add for the guidance of those who may read this, that I was the only member of the Cabinet who openly advised against invasion though it was plain that Mr Butler had doubts and I know that Mr Heathcoat Amory was troubled about it. Outside the Cabinet I was aware of a number of Ministers, apart from Mr Nutting and Sir Edward Boyle who resigned, who were opposed to the operation.

Naturally I anxiously considered whether I ought not to resign. Resignation at such a moment was not a thing lightly to be undertaken. I felt that I was virtually alone in my opinion in the Cabinet and that I had not the experience or the knowledge to make me confident in my own view when it was so strongly opposed by Eden, Salisbury, Macmillan, Head, Sandys, Thorneycroft, and Kilmuir; for all of whom I had respect and admiration.

I knew that if I did resign it was likely that the Government would fall, and I still believed that it was better for the country to have that Government than the alternative. What the Labour people had in mind was a kind of rump of the Tory Government led by Butler, which they would support. This could not last. Moreover, far more than I knew at the time, the ordinary man in the country was behind Eden.

In any case in the result I wrote to Eden telling him that, as the fact was, I was very far from fit and did not feel I could continue in my office as Minister of Defence. At the same time I told him in the letter that had it not been for my fundamental differences with my colleagues over the size of the forces, and over Suez, I should not have been tendering my resignation at that moment. He behaved very generously, accepted the position that I would not go on as Minister of Defence, but kept me in the Cabinet as Paymaster General, thus preserving the unity of the front.

(10) Walter Monckton, memorandum (7th November, 1956)

I have remained in the Cabinet without resignation because I have not thought it right to take a step which I was assured would bring the Government down. The view which I have always expressed has been against the armed intervention which has taken place on the grounds -

(a) that we should have half our own country and 90 per cent of world opinion against us;

(b) that it was difficult to justify intervention on behalf of the invader and against the country invaded;

(c) that it would inflame opinion against us in the Middle East and upset the whole of the Arab world;

(d) that it would jeopardise our relations with the US which were the foundation of our international and defence policy.

I have not changed my opinion on these matters, but I have always felt that, inasmuch as my opinion was not shared by any of my colleagues, a certain measure of humility demanded restraint in action on my part. Moreover, I did understand the danger of doing nothing because Nasser was succeeding in undermining our position throughout the Middle East and North Africa, and would continue to take similar steps in Africa as a whole if he were not prevented. I further understood that such a policy was really playing into the hands of the Soviet Government and that Russia at the end of the day would be the predominating power throughout the area concerned, and this I view, like my colleagues, with grave misgivings.

In all these circumstances I have never been able to convince myself that armed intervention was right, but I have not been prepared to resign. I have lived on from day to day, and am still so living on, in the hope that I could within the Cabinet contribute towards a settlement as soon as possible.

(11) Edward Heath, The Course of My Life (1988)

Throughout these weeks I was able to observe Eden closely. In particular, I watched the animated way in which he worked on his papers. As he went over telegram after telegram from our ambassadors at the United Nations and in the major capitals of the world, one could only admire the skill and the speed with which he worked. Like all the best leaders in peace and war, he seemed able to visualise the situation many moves ahead.

He was also able to make realistic assessments and imaginative proposals for dealing with them. The only exception I noticed was his readiness to accept the information coming in from the intelligence services in the Middle East. All too many of them were misleading enough taken at face value, but at times he seemed to read into them what he wanted. This was especially the case with regard to Nasser's personal position in Egypt and his relationship with other Middle Eastern countries. Eden was determined that Nasser and his regime should be brought down. The intelligence services often provided gossip and items of tittle-tattle which seemed to show that this was about to happen. But it never did and Nasser emerged more or less intact from the whole episode.

Secret discussions on the possibility of an invasion between the British, French and Israelis were carried out in Paris in the latter part of October. I was first told of these discussions after a meeting of the inner circle of Ministers and officials held at Chequers on 21 October. I was alarmed, but far from surprised, that a plan was being hatched to circumvent the negotiations in New York. Four days later, I went into the Cabinet Room as usual shortly before Cabinet was due to start, and I found the Prime Minister standing by his chair holding a piece of paper. He was bright-eyed and full of life. The tiredness seemed suddenly to have disappeared. 'We've got an agreement!' he exclaimed. 'Israel has agreed to invade Egypt. We shall then send in our own forces, backed up by the French, to separate the contestants and regain the Canal.' The Americans would not be told about the plan. He concluded, somewhat unnervingly, that 'this is the highest form of statesmanship'. The Sevres Protocol, as it became known, had been signed the day before, in a suburb of Paris. Sir Patrick Dean had signed on behalf of the Foreign Secretary, Selwyn Lloyd, and Christian Pineau and David Ben-Guiron had signed, respectively, on behalf of France and Israel. Only Lloyd, Macmillan, Butler and myself were to know about it. I did my utmost to change Eden's mind, warning him that it was unlikely that people would believe him - and that, even if the Protocol remained a secret and people accepted the official reason for going in, the very act of doing so was likely to split the country. Eden did not dispute any of this advice, but simply reiterated that he could not let Nasser get away with it.

Before we could have a proper discussion, the door opened and the Cabinet began to file in. At the meeting which followed, Eden repeated what he had said to our conference about the need to use force only if necessary. Although several Ministers had doubts about military action, the only one who actually resigned was Walter Monckton, the Minister of Defence. He was replaced by Antony Head on 18 October and took a non-departmental post. On 30 October, the Prime Minister interrupted business in the House at 4.30 p.m. to make a statement announcing that Israel had attacked Egyptian territory and was moving towards the Canal. At the same time it had given an undertaking that it would not attack Jordan or other neighbouring countries whose independence we were concerned to maintain.

As these debates proceeded, more and more questions were being asked and were remaining unanswered by an increasingly exposed, embarrassed and truculent government. In between the two front-bench wind-up speeches on Thursday 1st November, the drama moved on to another plane when the Conservative Member for the Wrekin, William Yates, interrupted on a point of order and said, "I have come to the conclusion that Her Majesty's Government has been involved in an international conspiracy," and the House had to be suspended amid considerable uproar.

(12) Statement issued by President Dwight Eisenhower (31st October, 1956)

As soon as the President received his first knowledge, obtained through press reports, of the ultimatum, he sent an urgent personal message to the Prime Minister of Great Britain and the Prime Minister of the Republic of France. The President has expressed his earnest hope that the United Nations Organization will be given full opportunity to settle the issue by peaceful means instead of by forceful ones.

(13) Anthony Eden, Full Circle (1965)

If the United States Government had approached this issue in the spirit of an ally, they would have done everything in their power, short of the use of force, to support the nations whose economic security depended upon the freedom of

passage through the Suez Canal. They would have closely planned their policies with their allies and held stoutly to the decisions arrived at. They would have insisted on restoring international authority in order to insulate the canal from the

politics of any one country. It is now clear that this was never the attitude of the United States Government. Rather did they try to gain time, coast along over difficulties as they arose and improvise policies, each following on the failure of

its immediate predecessor. None of these was geared to the long-term purpose of serving a joint cause.

(14) Harold Wilson, speech, House of Commons (12th November, 1956)

For the past fortnight, the House has debated the cost in political and moral terms of the Government's action in Suez. Today we have to count the reckoning in economic terms as well. When I say 'in economic terms' I do not mean merely the cost in terms of government expenditure. We are no longer in the days of nineteenth-century colonial wars, when the cost of these ventures could be reckoned in terms of another tuppence on the income tax or another penny on tea.

I hope that the Chancellor or the Minister of Supply will tell the House frankly today what, in the view of their advisers, will be the economic consequences of this military action. After all, it was long prepared. What estimates did the Government make of its costs and its economic consequences? What estimates do they make now?

(15) Anthony Eden, speech the House of Commons (December, 1956)

I want to say this on the question of foreknowledge, and to say it quite bluntly to the House, that there was not foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt, there was not. But there was something else. There was, we knew it perfetly well, a risk of it, and certain discussions and conversations took place as, I think, was absolutely right and as, I think, anybody would do. So far from this being an act of retribution, I would be compelled, and I think my colleagues would agree, if I had the same very disagreeable decisions to take again, to repeat them.

(16) Margaret Thatcher, The Path of Power (1995)

The balance of interest and principle in the Suez affair is not a simple one. I had no qualms about Britain's right to respond to Nasser's illegal seizure of an international waterway - if only action had been taken quickly and decisively. Over the summer, however, we were outmanoeuvred by a clever dictator into a position where our interests could only be protected by bending our legal principles. Among the many reasons for criticizing the Anglo-French-Israeli collusion is that it was bound to tarnish our case when it became known, as it assuredly would and did. At the same time, Suez was the last occasion when the European powers might have withstood and brought down a Third World dictator who had shown no interest in international agreements, except where he could profit from them. Nasser's victory at Suez had among its fruits the overthrow of the pro-Western regime in Iraq, the Egyptian occupation of the Yemen, and the encirclement of Israel which led to the Six Day War - and the bills were still coming in when I left office.

As I came to know more about it, I drew four lessons from this sad episode. First, we should not -get into a military operation unless we were determined and able to finish it. Second, we should never again find ourselves on the opposite side to the United States in a major international crisis affecting Britain's interests. Third, we should ensure that our actions were in accord with international law. And finally, he who hesitates is lost.

(17) Dennis Barker, The Guardian (26th March, 1968)

Mr William Clark, who resigned as Sir Anthony Eden's press secretary at the time of Suez, said yesterday that the "Manchester Guardian's" anti-Suez leading articles were one of the main reasons why the Prime Minister asked for the drawing up of an instrument to bring the BBC under direct Government control. The plan was never put into operation.

Mr Clark said that the "Manchester Guardian's" leaders critical of the Suez policy were being constantly quoted on the BBC and could be heard by troops overseas. The "Manchester Guardian's" diplomatic correspondent at the time, Mr Richard Scott, was frequently critical of Sir Anthony's policies when a guest on BBC discussion programmes.

According to Mr Clark, the resentment of the inner Cabinet was not discussed solely on the BBC, but the BBC happened to be the news service which most easily lent itself to direct Government action. "The fact was that there was a real attempt to pervert the course of news, of ordinary understanding of events. The BBC happened to be one place where Government action could most easily take place," said Mr Clark.