George Houser

George Houser, the son of a Methodist minister, became a pacifist while studying at the Theological Seminary in Chicago. Houser was influenced by Henry David Thoreau and his theories on how to use nonviolent resistance to achieve social change.

Houser joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the War Resisters League and in November, 1940, he was arrested for resisting the draft. Found guilty, he was sentenced to a year imprisonment in Danbury Federal Correctional Institution in Connecticut.

On his release from prison Houser became youth secretary of Fellowship of Reconciliation. Houser worked closely with Abraham Muste, the leader of the organisation, during the Second World War. Houser also helped Muste and Philip Randolph to organize the planned March on Washington in June, 1941 against racial discrimination in the armed forces. The demonstration was called off when Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 on 25th June, 1941, barring discrimination in defence industries and federal bureaus (the Fair Employment Act).

In 1942 Houser, and two other members of FOR, James Farmer and Bayard Rustin, established the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). Members of CORE had been deeply influenced by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign that he used successfully against British rule in India. The students became convinced that the same methods could be employed by African Americans to obtain civil rights in America.

Houser explained the tactics of CORE in 1945: "A person trying to practice non-violence will refuse to retaliate violently. He merely absorbs the physical punishment. This sounds crazy to the average person, who has been taught to protect himself by retaliating when attacked, even if he does take a beating in the process. Why, then, is non-retaliation essential to the non-violent approach? From the negative standpoint, if non-violence is forsaken by the minority group it means the police can be called to arrest them. From the positive point of view, non-retaliatory action may make possible the winning of the support of the public, of the police, and of the opposition."

In early 1947, the Congress on Racial Equality announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

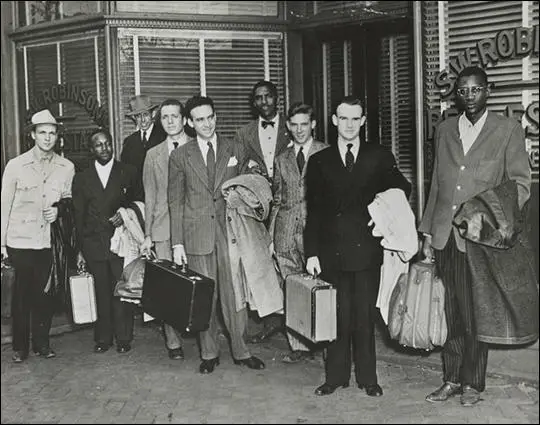

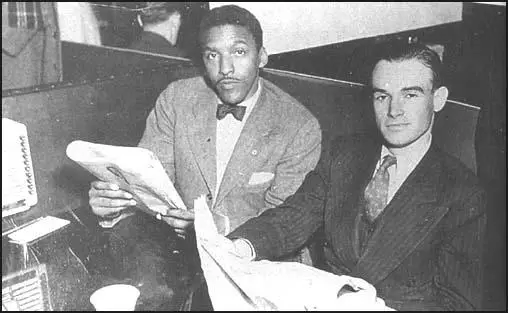

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included George Houser, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

Wallace Nelson, Ernest Bromley, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin,

Joseph Felmet, George Houser and Andrew Johnson.

James Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill Peck and four other members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your niggers with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress on Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

George Houser later wrote: "We in the non-violent movement of the 1940s certainly thought that we were initiating something of importance in American life. Of course, we weren't able to put it in perspective then. But we were filled with vim and vigor, and we hoped that a mass movement could develop, even if we did not think that we were going to produce it. In retrospect, I would say we were precursors. The things we did in the 1940s were the same things that ushered the civil rights revolution."

Houser ceased to be active in the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and he turned his attention to the struggle against colonialism in Africa. In 1952 he established Americans for South African Resistance (AFSAR), an organization that supported the African National Congress in its campaign against apartheid in South Africa. The following year he established the American Committee on Africa (ACOA). He served as Executive Director of the ACOA from 1955-1981 and of The Africa Fund from 1966-1981.

George Houser is the author of No One Can Stop the Rain: Glimpses of Africa’s Liberation Struggle (1989) and the co-author of I Will Go Singing: Walter Sisulu Speaks of his Life and the Struggle for Freedom in South Africa (2000).

Primary Sources

(1) George Houser, interviewed by Lisa Brock (19th July, 2004)

My father was a clergyman at Woodlawn Methodist Church in Cleveland and then in a church in Lisbon, Ohio for two years. I remember not really anything of this. Then my folks made a long move, from there to the Philippine Islands, 1919 to 1924, located in Manila. This is when I started remembering, because we left there just when I was to become eight. We left in March, I think, and I became eight en route home. I had my eighth birthday, I remember, in London. And then we were located for a year or so in western New York state. My father traveled for the Board of Missions of the Methodist Church - it was the Methodist Episcopal Church at that time. And we lived and I started school in Chautauqua, New York, in the very western part of the state - 50 miles west of Buffalo. We have just been there, again, on a visit. And, from there to Buffalo briefly, and then to Troy, New York where we spent six years. My father was the minister of what was called the Fifth Avenue-State Street Methodist Episcopal Church - a unification of two churches, the Fifth Avenue church and the State Street church.

From there to Berkeley, California. I was 15. Then my freshman year of high school in Troy and then started all over again at 10th grade, which was the first, freshman year at Berkeley High School. And we were there from 1931 until 1936. I went to China for a year as an exchange student. My folks moved from Berkeley to Denver. My father was the minister of the Trinity Methodist Church - Methodist Episcopal Church - in downtown, in the middle of Denver. They lived there and then subsequently—because your question had to do with my parents - they were back across the river here in Westchester in retirement teaching at a college, and then moved to California, and they were in San Luis Obispo and then went to a retirement home in Boulder, Colorado where they both died.

(2) In the journal, Equality, George Houser explained his views on non-violence (May, 1945)

A person trying to practice non-violence will refuse to retaliate violently. He merely absorbs the physical punishment. This sounds crazy to the average person, who has been taught to protect himself by retaliating when attacked, even if he does take a beating in the process. Why, then, is non-retaliation essential to the non-violent approach? From the negative standpoint, if non-violence is forsaken by the minority group it means the police can be called to arrest them. From the positive point of view, non-retaliatory action may make possible the winning of the support of the public, of the police, and of the opposition.

(3) Instructions produced by George Houser and Bayard Rustin for the Journey of Reconciliation (April, 1947)

If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat.

If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: "As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court".

If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move.

If the police asks you to "come along," without putting you under arrest, tell them you will not go until you are put under arrest.

If the police put you under arrest, go with them peacefully. At the police station, phone the nearest headquarters of the NAACP, or one of your lawyers. They will assist you.

(4) George Houser and Bayard Rustin, Fellowship Magazine (April, 1947)

On June 3, 1946, the Supreme Court of the United States announced its decision in the case of Irene Morgan versus the Commonwealth of Virginia. State laws demanding segregation of interstate passengers on motor carriers are now unconstitutional, for segregation of passengers crossing state lines was declared an "undue burden on interstate commerce." Thus it was decided that state Jim Crow laws do not affect interstate travelers. In a later decision in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, the Morgan decision was interpreted to apply to interstate train travel as well as bus travel.

The executive committee of the Congress of Racial Equality and the racial-industrial committee of the Fellowship of Reconciliation decided that they should jointly sponsor a "Journey of Reconciliation" through the upper South, in order to determine to how great an extent bus and train companies were recognizing the Morgan decision. They also wished to learn the reaction of bus drivers, passengers, and police to those who nonviolently and persistently challenge Jim Crow in interstate travel.

During the two-week period from April 9 to April 23, 1947, an interracial group of men, traveling as a deputation team, visited fifteen cities in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. More than thirty speaking engagements were met before church, NAACP, and college groups. The sixteen participants were:

Negro. Bayard Rustin, of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and part-time worker with the American Friends Service Committee; Wallace Nelson, freelance lecturer; Conrad Lynn, New York attorney; Andrew Johnson, Cincinnati student; Dennis Banks, Chicago musician; William Worthy, of the New York Council for a Permanent FEPC; Eugene Stanley, of A. and T. College, Greensboro, North Carolina; Nathan Wright, church social worker from Cincinnati.

White. George Houser, of the FOR and executive secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality; Ernest Bromley, Methodist minister from North Carolina; James Peck, editor of the Workers Defense League News Bulletin; Igal Roodenko, New York horticulturist; Worth Randle, Cincinnati biologist; Joseph Felmet, of the Southern Workers Defense League; Homer Jack, executive secretary of the Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination; Louis Adams, Methodist minister from North Carolina.

During the two weeks of the trip, twenty-six tests of company policies were made. Arrests occurred on six occasions, with a total of twelve men arrested.

(5) George Houser, interviewed by Jervis Anderson for his book, A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait (1972)

We in the non-violent movement of the 1940s certainly thought that we were initiating something of importance in American life. Of course, we weren't able to put it in perspective then. But we were filled with vim and vigor, and we hoped that a mass movement could develop, even if we did not think that we were going to produce it. In retrospect, I would say we were precursors. The things we did in the 1940s were the same things that ushered the civil rights revolution. Our Journey of Reconciliation preceded the Freedom Rides of 1961 by fourteen years. Conditions were not quite ready for the full-blown movement when we were undertaking our initial actions. But I think we helped to lay the foundations for what followed, and I feel proud of that.

(6) George Houser, No One Can Stop the Rain: Glimpses of Africa’s Liberation Struggle (1989)

My introduction to the African liberation struggle began with the "Campaign to Defy Unjust Laws," sponsored by the African National Congress. The year was 1952. Word about plans for the forthcoming massive nonviolent Defiance Campaign to resist the apartheid laws came to me from my friend and co-worker Bill Sutherland through a South African editor whom he had met in London. Sutherland and I were both pacifists, and had worked together on numerous projects to combat segregation in the United States by non-violent methods.

(7) Margalit Fox, New York Times (20th August, 2015)

The Rev. George M. Houser, a founder of the Congress of Racial Equality who was believed to be the last living member of the inaugural Freedom Ride - the volatile, sometimes violent bus trip through the South by a racially mixed group in 1947 - died on Wednesday in Santa Rosa, Calif. He was 99.

His son Steven confirmed the death.

A white Methodist minister who appeared constitutionally averse to limelight, Mr. Houser was “one of the most important yet least-heralded activists of the 20th century,” the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist organization with which he was long involved, wrote on its website in June, on the occasion of his 99th birthday.

With an African-American colleague, James Farmer, and others, Mr. Houser founded CORE in 1942.

Five years later, he and Bayard Rustin of CORE organized the first test of a United States Supreme Court ruling that barred segregation on interstate transit. Their campaign, called the Journey of Reconciliation, sent black and white riders through the South on interstate buses — an act of great personal risk that met with acceptance in some cities and arrests and bloodshed in others.

That voyage, in which Mr. Houser and Mr. Rustin both took part, prefigured the Freedom Rides of 1961 by 14 years and is now widely described as having been the first of them.

Mr. Houser, who had been imprisoned shortly before the United States entered World War II for declaring himself a conscientious objector, was in later years deeply involved in efforts to end apartheid in South Africa.

George Mills Houser was born in Cleveland on June 2, 1916. The son of missionaries, he spent part of his boyhood in the Philippines, and afterward lived wherever his father took a pulpit: Troy, N.Y.; Berkeley, Calif.; and Denver.

After studying at what is now the University of the Pacific in Stockton, Calif., the young Mr. Houser completed his undergraduate work at the University of Denver. He entered graduate school at Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he was chairman of the seminary’s social action committee.

Deeply influenced by the work of Henry David Thoreau and Gandhi, Mr. Houser joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1938, while a student there.

In 1940, he and a group of classmates, including David Dellinger, who went on to become a member of the Chicago Seven, refused to register for the draft as mandated by the Selective Training and Service Act. The act had been signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt that year.

Mr. Houser, Mr. Dellinger and six fellow students were sentenced to prison in November 1940. Their story was the subject of a 2000 PBS documentary, “The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It.”

After serving a year in the federal prison at Danbury, Conn., Mr. Houser joined the staff of the Fellowship of Reconciliation as its youth secretary. He later moved to Chicago, where he completed his divinity degree at the Chicago Theological Seminary and received ordination.

In 1942, after Mr. Houser and his friend Mr. Farmer were denied service at a Chicago restaurant, they and others established what became CORE. Mr. Houser served as the group’s first executive secretary.

CORE soon became a national organization, enrolling tens of thousands of members in dozens of chapters within its first few years. Endorsing nonviolent protest, it convened sit-ins in public accommodations around the country.

In 1946, ruling in a landmark case, Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, the Supreme Court held that segregation on interstate transit was unconstitutional.

The next year, to test the ruling, Mr. Houser and Mr. Rustin, CORE’s first field secretary, organized the Journey of Reconciliation. They convened a team of 16 men — eight black and eight white — to ride interstate buses through the South.

The instructions that Mr. Houser and Mr. Rustin issued to the riders included these:

“If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat.

“If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: ‘As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court.’

“If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move.”

Over two weeks in April 1947, the team traveled to 15 cities in Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky. Its members were arrested, jailed and sometimes beaten. In North Carolina, Mr. Rustin and another black rider, Andrew Johnson, were sentenced to 30 days on a chain gang for violating the state’s Jim Crow laws.

In 1948, for their efforts to ensure the desegregation of interstate travel, Mr. Houser and Mr. Rustin received the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy from the Council Against Intolerance in America.

Mr. Houser, who in 1952 helped found the group Americans for South African Resistance, became the executive director of the American Committee on Africa in 1955. In that post, which he held until his retirement in 1981, he worked to abolish apartheid and to end colonial rule throughout Africa.

For his work, Mr. Houser received the Oliver R. Tambo Award from President Jacob Zuma of South Africa in 2010. Named for the former African National Congress president who spent three decades in exile, the award recognizes foreign nationals for service to South Africa.

A longtime resident of Pomona, N.Y., Mr. Houser lived most recently in Santa Rosa. Besides his son Steven, his survivors include his wife, the former Jean Walline, whom he married in 1942; two other sons, David and Thomas; a daughter, Martie Leys; nine grandchildren; and eight great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rustin died in 1987, Mr. Farmer in 1999.

Mr. Houser was the author of several books, including “No One Can Stop the Rain: Glimpses of Africa’s Liberation Struggle” (1989) and, with Herb Shore, “Mozambique: Dream the Size of Freedom” (1975).