On this day on 28th December

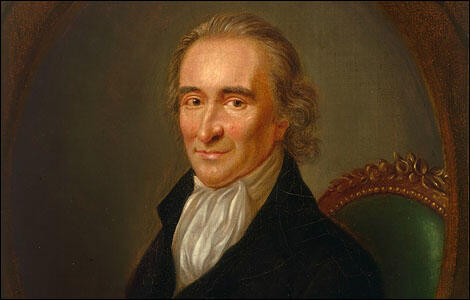

On this day in 1793 Tom Paine was arrested by the French government and kept in prison under the threat of execution. In 1792 Tom Paine became a French citizen and was elected to the National Convention. Paine upset French revolutionaries when he opposed the execution of Louis XVI. Paine was only released after the American minister, James Monroe, put pressure on the French government.

While in prison Tom Paine worked on book on the subject of religion. Age of Reason was published soon after his release and caused a tremendous impact because it questioned the truth of Christianity. Paine criticised the Old Testament for being untrue and immoral and claimed that the Gospels contained inaccuracies and contradictions.

In 1802 Paine moved back to America but the Age of Reason had upset a large number of people and he discovered that he had lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the War of Independence. Unable to return to Britain, Paine remained in America until his death in New York on 8th June 1809. By the time he had died, over 1,500,000 copies of The Rights of Man had been sold in Europe.

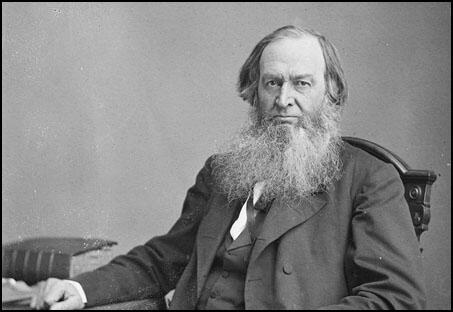

On this day in 1802 John Roebuck, the son of Ebenezer Roebuck, a civil servant in the East India Company, was born in Madras in India. When John's father died in 1807 his mother brought the family back to England. She remarried and in 1815 John was taken to Canada to live.

Roebuck returned to England at the age of twenty-two to study law at the Inner Temple in London. He joined the Utilitarian Society became friendly with John Stuart Mill. Roebuck became active in the campaign for increasing the franchise and after the 1832 Reform Act was selected to represent the Whigs at Bath.

After entering the House of Commons he caused a stir by promoting a wide-range of radical policies including the expropriation of the property of the Church of England. Although accused of preaching open rebellion he retained his Bath seat in the 1835 General Election.

In 1834 Roebuck led the campaign to free the Tolpuddle Martyrs and called for the repeal of the Corn Laws. Roebuck joined with Francis Place and Joseph Hume to produce a volume of essays entitled Pamphlets for the People (1835). In one of these pamphlets, The Stamped Press and its Morality, Roebuck attacked the 1815 Stamp Act that had placed a 4d tax on newspapers. Roebuck criticised those newspaper owners who accepted this law. The editor of the Morning Chronicle was so upset he challenged Roebuck to a duel. Roebuck accepted and survived and later that year welcomed the decision to reduce the tax to one penny.

In June 1836, John Roebuck joined forces with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, Henry Vincent and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands.

(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

(ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period."

John Roebuck had now completely broken with the Whigs and described them as "an exclusive and aristocratic faction, though at times employing democratic principles and phrases as weapons of offence against their opponents. When out of office they are demagogues; in power they become exclusive oligarchs." Without the support of the Whigs, Roebuck lost his Bath seat in the 1837 General Election.

Out of the House of Commons Roebuck's views became less extreme and in the 1841 General Election won Bath again. He supported the reforms of Robert Peel, but he remained radical on some issues and spoke out in favour of the Chartist movement and helped present their petition to Parliament in 1842.

Defeated at Bath in the 1847 General Election, Roebuck moved to Sheffield and was re-elected to the House of Commons in a by-election in 1849. Roebuck upset his radical friends by losing interest in domestic reform. After his election he supported the aggressive foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. This was popular with his constituents and he was re-elected in 1852, 1857, 1859 and 1865.

The views expressed by John Roebuck became increasingly conservative. He admitted in 1864 that: "the hopes of my youth and manhood are destroyed and I am left to reconstruct my political philosophy". Although a long-term supporter of universal suffrage, during the debate on the 1867 Reform Act he warned against placing political power "in the hands of the ignorant". Roebuck denounced the activities of trade unionists in what became known as the Sheffield Outrages and opposed his party leader, William Gladstone, when he attempted to disestablish the Anglican Church in Ireland. By this time the members of the Liberal Party in Sheffield were totally disillusioned with Roebuck and selected another candidate for the forthcoming parliamentary election. Roebuck stood as an Independent but was easily defeated in the 1868 General Election.

With the support of the Conservative Party, Roebuck won the Sheffield seat in the 1874 General Election. In the House of Commons he denounced William Gladstone as a "bastard philanthropist" and praised the policies of Benjamin Disraeli. John Roebuck died of heart failure on 30th November 1879.

On this day in 1829 Bill Richmond died in London. Richmond, the son of former slaves from Georgia, was born in New York in 1763. He entered the service of the future Duke of Northumberland and at the age of 14 was brought to England.

After attending school he was apprenticed to a cabinet-maker in York. Although weighing less than 11 stone, Richmond took up boxing and developed a reputation for beating much larger men.

Richmond became a prize fighter and scored a notable victory when he defeated Jack Holmes over 26 rounds at Kilburn. However, he lost to the great Tom Cribb after a long fight at Hailsham in Sussex.

In his next contest he beat Jack Carter at Epsom Downs. In 1809 he won 100 guineas after beating George Maddox after a hard fought 52 rounds.

Richmond retired from the ring after marrying a rich woman who helped him to buy a fashionable public house, the Horse and Dolphin, near Leicester Square. He also ran a boxing academy where he taught young men how to fight. One of his pupils was the writer William Hazlitt.

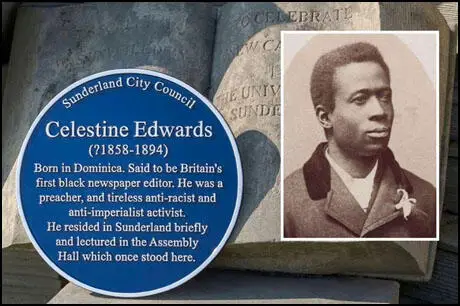

On this day in 1858 Celestine Edwards, the youngest of nine children, was born on the island of Dominica on 28th December, 1858. At the age of 12 he became a sailor. During the next few years he developed radical opinions about politics and became a strong supporter of human rights.

In the 1870s Edwards he settled in Edinburgh, Scotland. He became involved in the temperance movement. Later he lived in Sunderland before moving to London. Edwards worked as a building labourer but in his spare time he made speeches in Victoria Park about issues such as slavery.

Edwards helped Walter Hawkins write his autobiography, From Slavery to Bishopric (1891). Hawkins, a former slave, eventually became a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada. He also became editor of the weekly Christian newspaper, Lux (1892-1895). Edwards also became executive secretary of the Society for the Recognition of the Brotherhood of Man and edited its monthly journal, Fraternity (1893-1897).

Edwards continued to make public speeches. In Bristol on 3rd July, 1893, Edwards spoke on lynching in the United States. The following week he spoke to 1,200 people in London on "American Atrocities". In August he was in Liverpool lecturing on 'Blacks and Whites in America'. Similar talks were given in Plymouth, Aberdeen, Newcastle, Edinburgh and Glasgow. Popular topics included 'The Negro Race and Social Darwinism' and 'Liquor Traffic to West Africa'.

Celestine Edwards had a strong desire to become a doctor and enrolled at the London Hospital. However, his health was poor, and in May 1894 he returned to his family in Dominica. He died at his brother's house on 25th July, 1894.

On this day in 1860 artist Philip Wilson Steer, the youngest of three children (one brother, Henry, one sister, Catherine) of Philip Steer (1810–1871) and his wife, Emma Harrison (1816–1898), was born in Birkenhead on 28th December, 1860. His father was an artist who painted landscapes and portraits in the style of Joshua Reynolds.

Steer was educated Hereford Cathedral School. In 1878 he enrolled at Gloucester School of Art in 1881 and the following year was spent at the drawing schools of the Department of Science and Art in South Kensington.

In 1882 Steer then spent time at the Académie Julian, where he got to know Frederick Brown. According to his biographer, Ysanne Holt: "In Paris he remained securely within a circle of English and American students and was largely unaware of more recent developments in French art. Following the introduction of a French language examination at the école he returned to England the next summer." Steer acquired a studio in Manresa Road, Chelsea, and spent his summers at Walberswick in Suffolk.

Steer was one of the founders of the New English Art Club in 1886, a group of British artists who felt their work was neglected by the Royal Academy. His friend, Frederick Brown, drew up the constitution, sat on all the committees and juries, and encouraged his Slade students to exhibit there. Around 50s took part in the inaugural exhibition held at the Marlborough Gallery in April, 1886. Early exhibitors included George Clausen, John Singer Sargent, Colin Gill, Walter Sickert and James Whistler. Steer exhibited Girls Running, Walberswick (1886) A Summer's Evening (1887) and Knucklebones (1889).

In 1892 Frederick Brown succeeded Alphonse Legros as professor of fine art Slade Art School. According to Anne Pimlott Baker: "Continuing the teaching and liberal outlook of Poynter and Legros, he (Brown) built up the school of drawing, and tried to develop the individuality of his pupils, while encouraging them to study form by means of an analytical rather than an imitative approach to draughtsmanship, returning to the methods of masters such as Ingres. He attracted a strong teaching staff, establishing the principle that all teachers should be practising artists." Brown recruited Steer to the staff.

Students who studied under Brown include Augustus John, Gwen John, William Orpen, Paul Nash, Wyndham Lewis, Dora Carrington, Edith Craig, Dorothy Brett, Mark Gertler, Christopher Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, John S. Currie, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson, Rudolph Ihlee, Spencer Gore, Jacob Epstein, David Bomberg, Michel Salaman, Edna Waugh, Herbert Barnard Everett, Albert Rothenstein, Ambrose McEvoy, Ursula Tyrwhitt, Ida Nettleship and Gwen Salmond.

During the First World War the government established the War Propaganda Bureau. Early in 1918 the government decided that a senior government figure should take over responsibility for propaganda. On 4th March Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express, was made Minister of Information. Under him was Charles Masterman (Director of Publications) and John Buchan (Director of Intelligence). Lord Northcliffe, the owner of both The Times and the Daily Mail, was put in charge of all propaganda directed at enemy countries. Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was appointed director of propaganda in neutral countries. On the announcement in February 1918, David Lloyd George was accused in the House of Commons of using this new system of getting control over all the leading figures in Fleet Street.

Beaverbrook decided to rapidly expand the number of artists in France. He established with Arnold Bennett a British War Memorial Committee (BWMC). The artist chosen for this programme were given different instructions to those sent previously. Beaverbrook told them that pictures were "no longer considered primarily as a contribution to propaganda, they were now to be thought of chiefly as a record."

Artists sent abroad under the BWMC programme included Steer, John Singer Sargent, Augustus John, John Nash, Henry Lamb, Henry Tonks, Austin Osman Spare, Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Colin Gill, William Roberts, Wyndham Lewis, Stanley Spencer, Philip Wilson Steer, George Clausen, Bernard Meninsky, Charles Pears, Sydney Carline, David Bomberg, Gilbert Ledward and Charles Jagger. His most popular painting for the BWMC was Mine-Sweepers at Dover (1918).

Steer's biographer, Ysanne Holt, has pointed out: "Throughout the 1920s Steer increasingly experimented with watercolour, a technique which provided him with a route out of the heavy impasto characteristic of his oils. These watercolours, impressionist in the strictest sense of the term, partly reflect the later works of Turner, but also signal a return to Monet and to a Whistlerian approach - the handling is slight, shapes and objects are suggested, and all unnecessary detail eliminated. For the painter himself the processes of watercolour were a fascination and the best examples he regarded merely as flukes, which either did or did not come off".

In 1930 Steer and his great friend, Henry Tonks, both retired from the Slade Art School. He continued painting landscapes and waterscapes until 1938 when his eyesight became too bad to go on. He commented that he "had painted enough and many people painted far too many pictures". Philip Wilson Steer died at his home of bronchitis on 21st March 1942.

On this day in 1871 Frederick Pethick-Lawrence was born. Frederick Lawrence, the son of Alfred Lawrence, the owner of a building company, was born in London on 28th December 1871. His wealthy parents were Unitarians and members of the Liberal Party. Frederick was educated at Eton (1985-1891) and one of his teachers wrote: "He is certainly a real good sterling lad full of every manly quality. Wherever he goes he will do honour to himself and to all who who are for him among whom I reckon myself one of the first."

Lawrence also did well at Trinity College. After three years studying maths, he stayed on for a further three to read natural sciences. Eventually he achieved a Double First and became President of the Union. According to Fran Abrams: "In 1897 he was made a fellow of his college and seemed set for an academic career. But other influences were already at work. Fred's political consciousness was being honed through the contacts he was making at Cambridge." This included Alfred Marshall, who argued that the knowledge of economics should be applied to help the poor. While studying to become a lawyer, Lawrence gave free legal advice at the Nonconformist settlement Mansfield House in the slums of East London. He also worked with Charles Booth collecting information on poverty in the area (Life and Labour of the People, Volume IX).

Lawrence was called to the bar by the Inner Temple in 1899. The death of his elder brother in 1900 made him wealthy, and in the following year he was selected as the Liberal Party candidate for North Lambeth. While working with the poor Frederick Lawrence met the social worker, Emmeline Pethick. The couple fell in love but Emmeline refused to marry Frederick because he did not share her socialist beliefs. It was not until 1901, when Frederick had been converted to socialism, that Emmeline agreed to marry him. On marriage, he added his wife's name to his own and joined the Labour Party.

Soon after her marriage Emmeline thought she was pregnant. Frederick wrote that the birth "will make us both extra happy". He added: "Isn't it splendid dear. My heart just singing and singing and won't keep quiet." However, Emmeline suffered a miscarriage and received news that she could not have children. Frederick wrote to her: "I am to you a splendid husband and you to me a splendid wife and it is enough!"

Pethick-Lawrence became a close friend of James Keir Hardie. He later commented: "He was, in fact, the exact opposite of the uncouth and unpractical iconoclast, which those whose privileges he threatened painted him. He was the most sensitive person I have ever known in my life, and if he was unconventional it was because he had to be, in order to achieve his purpose."

In 1901 Frederick Pethick-Lawrence became the owner of The Echo, a left-wing evening newspaper. He recruited friends from the socialist movement such as Ramsay MacDonald and H. N. Brailsford to write for the newspaper. Frederick also published and edited the monthly, Labour Record and Review (1905-07). Emmeline later argued: "His outstanding qualities of intellect, balanced judgment and practical administration in business and finance became the rock upon which I have built, since then, the structure of my life."

In 1906 James Keir Hardie introduced Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence to Emmeline Pankhurst. As a result Emmeline joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The organisation did not allow men to become members but Frederick used his legal training to represent the WSPU in court. He later stated that he did this to prevent a "sex war". According to his biographer, Brian Harrison: "He provided much needed level-headed financial, organizational, and legal expertise, and published extensively for the cause. Already in 1906 he was supporting suffragettes in the law courts, guiding them in self-defence, and standing bail for more than 100 of them." Pethick-Lawrence also pledged £1,000 a year to the WSPU.

In 1907 Frederick and Emmeline started the journal Votes for Women. Between 1908 and 1909 the circulation of the newspaper to 30,000. The Pethick-Lawrence's large home in London became the office of the WSPU. It was also used as a kind of hospital where women made ill by their prison experiences could recover their strength before embarking on further militant acts. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence served six terms of imprisonment for her political activities during this period.

In 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Frederick and Emmeline both disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. As soon as this wholesale smashing of shop windows began, the government ordered the arrest of the leaders of the WSPU. Christabel escaped to France but Frederick and Emmeline were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. They were also successfully sued for the cost of the damage caused by the WSPU.

They both went on hunger strike and had to face the full rigours of forcible feeding twice a day for several days. He later recalled the experience in his memoirs, Fate Has Been Kind (1943): "The head doctor, a most sensitive man, was visibly distressed by what he had to do. It certainly was an unpleasant and painful process and a sufficient number of warders had to be called in to prevent my moving while a rubber tube was pushed up my nostril and down into my throat and liquid was poured through it into my stomach. Twice a day thereafter one of the doctors fed me in this way. I was not allowed to leave my cell in the hospital and for the most part I had to stay in bed. There was nothing to do but to read; and the days were very long and went very slowly."

Christabel Pankhurst later recorded: "Mother and Mr. and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence went on hunger-strike. The Government retaliated by forcible feeding. This was actually carried out in the case of Mr. and Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence. The doctors and wardresses came to Mother's cell armed with forcible-feeding apparatus. Forewarned by the cries of Mrs. Pethick-Lawrence… Mother received them with all her majestic indignation. They fell back and left her. Neither then nor at any time in her log and dreadful conflict with the government was she forcibly fed."

After Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were released from prison they began to speak openly about the possibility that this window-smashing campaign would lose support for the WSPU. At a meeting in France, Christabel told Emmeline and Frederick about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. As Brian Harrison has pointed out: "The Pethick-Lawrences, concealing their private bitterness at how they had been treated, continued to edit Votes for Women, gathered the Votes for Women Fellowship around it, and in 1914 eventually merged it with the United Suffragists, a bridge-building body aiming to draw together suffragists of both sexes, and to unite militants with non-militants."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003) wrote: "Even the split with the WSPU did not end of this agony - the Pethick-Lawrences were still facing bankruptcy proceedings. An auction of their belongings was held at The Mascot, but raised only £300 towards their £1,100 court costs even though many friends arrived to buy personal possessions and give them back to the couple. Even the auctioneer returned to them a trinket he had bought as a keepsake. The rest of the costs were later taken from Fred's estate, plus a further £5,000 for repairs to shop windows damaged in the raids. Fortunately he had deep pockets and did not have to sell his home."

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, David Lloyd George (Chancellor of the Exchequer), Charles Trevelyan (Parliamentary Secretary of the Board of Education), John Burns (President of the Local Government Board) and John Morley (Secretary of State for India), were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The day after war was declared, Charles Trevelyan began contacting friends about a new political organisation he intended to form to oppose the war. This included two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control (UDC).

Pethick-Lawrence was also opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War and joined the UDC. He later recalled: "I joined the Union of Democratic Control and became its treasurer. As its name implies, it was founded to insist that foreign policy should in future, equally with home policy, be subject to the popular will. The intention was that no commitments should be entered into without the peoples being fully informed and their approval obtained. By a natural transition, the objects of the Union came to include the formation of terms of a durable settlement, on the basis of which the war might be brought an an end."

Other members of the UDC included Arthur Ponsonby, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Norman Angell, Arnold Rowntree, Philip Morrel, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Ramsay, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Morgan Philips Price.Over the next couple of years the UDC became the leading anti-war organisation in Britain.

Pethick-Lawrence was treasurer of the Union of Democratic Control(UDC) and in the spring of 1917 was chosen as the organisation's candidate in the South Aberdeen by-election. Pethick-Lawrence obtained only 333 votes whereas the government representative won with 3,283 votes. Although he was forty-six years old, the government attempted to conscript Pethick-Lawrence in 1917. He refused but instead of being imprisoned he was assigned to a farm in Sussex until the end of the war.

In the 1923 General Election Pethick-Lawrence won the Leicester seat for the Labour Party. He had the satisfaction of beating his old political opponent, Winston Churchill. Although an expert on economics, Pethick-Lawrence was a poor orator and he failed to shine in debates in the House of Commons. As a result, he was not given a post in the 1924 Labour Government.

After the Labour Party victory in the 1929 General Election, Ramsay MacDonald appointed Pethick-Lawrence as Financial Secretary under Philip Snowden. Pethick-Lawrence disagreed with Snowden's decision to cut public spending and in 1931 resigned from the government. Like most Labour MPs who opposed MacDonald's National Government, Pethick-Lawrence lost his seat in the 1931 General Election.

In 1931 G.D.H. Cole created the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda (SSIP). This was later renamed the Socialist League. Pethick-Lawrence joined the organisation and other members included William Mellor, Charles Trevelyan, Stafford Cripps, H. N. Brailsford, D. N. Pritt, R. H. Tawney, Frank Wise, David Kirkwood, Clement Attlee, Neil Maclean, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Alfred Salter, Jennie Lee, Gilbert Mitchison, Harold Laski, Frank Horrabin, Ellen Wilkinson, Aneurin Bevan, Ernest Bevin, Arthur Pugh, Michael Foot and Barbara Betts. Margaret Cole admitted that they got some of the members from the Guild Socialism movement: "Douglas and I recruited personally its first list drawing upon comrades from all stages of our political lives." The first pamphlet published by the SSIP was The Crisis (1931) was written by Cole and Bevin.

According to Ben Pimlott, the author of Labour and the Left (1977): "The Socialist League... set up branches, undertook to promote and carry out research, propaganda and discussion, issue pamphlets, reports and books, and organise conferences, meetings, lectures and schools. To this extent it was strongly in the Fabian tradition, and it worked in close conjunction with Cole's other group, the New Fabian Research Bureau." The main objective was to persuade a future Labour government to implement socialist policies.

Pethick-Lawrence concern at the emergence of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany resulted in rejecting pacifism in favour of collective security through the League of Nations. As Labour candidate for Edinburgh East at the General Election of 1935 he won 43 per cent of the votes cast in a three-cornered contest. On his arrival in the House of Commons he immediately attacked the Hoare–Laval pact.

Pethick-Lawrence won his seat in the 1945 General Election and the new British prime minister, Clement Attlee, appointed him as Secretary of State for India. Along with Stafford Cripps, Pethick-Lawrence was involved in the negotiations that took place in India during 1947. When Indian Independence was achieved, Pethick-Lawrence served as chairman of the East and West Friendship Council.

According to his biographer, Brian Harrison: "His mind combined opposites: on the one hand rationalistic and in many respects radical, he was at the same time highly sentimental (especially in religion and personal relations) and also traditionalist - proud of British institutions, eager to keep up with old friends, and an enthusiast for commemorating anniversaries. His mathematical mind might have led him to take black and white views in politics, and yet he was a lifelong enthusiast for compromise and for the British institutions which encouraged it."

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence remained active in politics until 1950 when she had a serious accident that left her immobilized. Frederick looked after Emmeline until she died of a heart attack at her home at Gomshall, Surrey, on 11th March 1954. He wrote to a friend: "I feel a bit dazed. It is as though I was at a violin concerto with the violinist absent."

Pethick-Lawrence married Helen Craggs, a former leading figure in the WSPU, in February 1957. He wrote to a friend, that Emmeline had told him the greatest compliment a man could pay to his dead wife was to marry again, "so I feel I have her blessing in advance". Frederick Pethick-Lawrence died on 10th September, 1961.

On this day in 1874 Gerrit Smith died. Smith was born in Utica, New York, Hampton, Connecticut, on 7th March, 1797. He came from a wealthy family and used some of his money to fund the campaign for temperance.

In 1835 Smith joined the Anti-Slavery Society after witnessing its speakers being attacked by a wild mob in Utica. Five years later he played a leading role in the formation of the anti-slavery Liberty Party. He was their unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1848 and 1852.

Smith used his considerable wealth to set up communities of freed black slaves, this included a settlement in Virginia where John Brown established a refuge for runaway slaves. He was unaware that Brown used some of the money that he supplied to fund the raid on Harper's Ferry in October 1859.

On this day in 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality in the Freewoman. Marsden argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

Dora argued that it would be better if women had a series of monogamous relationships. Les Garner, the author of A Brave and Beautiful Spirit (1990) has argued: "How far her views were based on her own experience it is difficult to tell. Yet the notion of a passionate but not necessarily sexual relationship would perhaps adequately describe her friendship with Mary Gawthorpe, if not others too. Certainly, her argument would appeal to single women like herself who had sexual desires and feelings but were not allowed to express them - unless, of course, in marriage. Even then, sex, for women at least, was supposed to be reserved for procreation."

On this day in 1918 Constance Markievicz becomes the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons. Constance Gore-Booth, the third child of Sir Henry Gore-Booth, was born on 4th February, 1868. Her sister was Eva Gore-Booth. She lived at Lissadell House in County Sligo. Her biographer, has pointed out: "Taking advantage of the family's extensive grounds Constance Gore-Booth enjoyed country pursuits, including hunting, driving, and riding, and became especially well known for her skill with the rifle and in the saddle. With Eva she was educated by governesses at home, her tutelage consisting mainly of instruction in the genteel arts of poetry, music, and art appreciation."

In 1886 she made a grand tour of the continent, and in the following year was presented to Queen Victoria. Her father, Sir Henry Gore-Booth, always attempted to act as a good landlord and provided free food for his tenants during the 1879-80 famine. It was probably the example of Gore-Booth that help develop in his two daughters, Constance and Eva Gore-Booth, a deep concern for the poor.

In 1893 Constance moved to London to study art at the Slade. It was at this time that she joined the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Later she moved to France where she continued her studies at the Julian School in Paris. In 1896 she joined with Eva Gore-Booth, to establish the Sligo Women's Suffrage Association.

While in France Constance met and married Count Casimir Markiewicz, a Polish-Russian nobleman. Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "Like Constance Markiewicz he had thrown over the life allotted to him - in his case the study of law in Kiev - to travel to Paris and become an artist. Despite these seemingly good portents her announcement in early 1900 that she intended to marry Casi caused a certain amount of consternation."

They married in 1900 and and their daughter, Maeve, was born the following year. The couple moved to Paris in 1902 and their daughter was left in the care of Lady Gore-Booth. They returned to Dublin and Constance developed a reputation as a talented landscape artist. She also acted in several plays at the Abbey Theatre and joined Maud Gonne as a member of revolutionary group, the Daughters of Ireland.

Constance Markievicz continued to be interested in the struggle for women's rights. In one speech she said: "We are told the principal argument against our having votes is that we don't make noise enough. Of course it is an excellent thing to be able to make a good deal of noise, but not having done so seems hardly a good enough reason for refusing the franchise." In 1908 she joined Eva Gore-Booth, Esther Roper, May Billinghurst, Annie Kenney and Adela Pankhurst in the campaign against Winston Churchill in the parliamentary election in Manchester North West.

In 1908 Constance became a member of Sinn Fein, an organization formed by Arthur Griffith six years earlier. The following year she founded Fianna Eireann, the youth movement of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. In 1911 Constance Markiewicz was arrested with Helena Moloney when they took part in a demonstration against the visit of George V to Ireland.

Constance Markiewicz joined James Connolly, James Larkin and Maud Gonne in the campaign to force the authorities to extend the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act to Ireland. She also started a scheme to feed poor children in Dublin and provided a soup kitchen in Liberty Hall during the lockout of unionized workers in 1913. Later that year she was elected Honorary treasurer to the Irish Citizen Army.

During the Easter Rising in April 1916, Constance Markiewicz was appointed second in command to Michael Mallin in St Stephen's Green. After a week of intense fighting Markievicz and her fellow rebels surrendered. After her arrest was charged with treason and sentenced to death. Her sister, Eva Gore-Booth, organised the successful campaign against her death sentence. It was eventually commuted to penal servitude for life because the authorities were unwilling to execute a woman. She was almost the only leader of the uprising to have survived.

Constance Markiewicz served fourteen months of her sentence at Aylesbury Prison before being released in the general amnesty of June 1917. She was immediately elected to the executive of Sinn Fein. Soon afterwards she was imprisoned again for her part in the campaign against the conscription of Irish men into the British Army.

After the passing of the passing of the Qualification of Women Act, Constance, while in prison, stood as the Sinn Fein candidate for the St. Patrick's division of Dublin. She was the only woman who was successful in the 1918 General Election. However, like the seventy two Sinn Fein MPs, she did not attend the House of Commons in London.

Released from prison in March 1919 she was appointed secretary for labour in the first Dáil Éireann. She was arrested again in June for making a seditious speech, and was sentenced to four months' hard labour - her third prison term in four years. After another arrest a sentence of two years' hard labour in the following year was interrupted by the general amnesty that followed the signing of the Irish Peace Treaty.

Constance Markiewicz was elected to the Irish Free State parliament in August 1923. She was arrested for the last time in November 1923 but was released soon after she went on hunger strike in protest. She joined Fianna Fáil on its establishment in 1926 and stood successfully as a candidate for the new party in the general election of 1927.

Her biographer, Anne Marreco, commented: "The young intellectual republicans who met her during these last years of her life found it hard to penetrate the mask of tense exhaustion, the gum-chewing, the chain-smoking, the shabby clothes, in order to perceive the exceptional being that still lay behind the ruins of her beauty and her physical elan."

Constance Markievicz died of peritonitis at Sir Patrick Dun's Hospital in Dublin on 15th July 1927 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in the city.

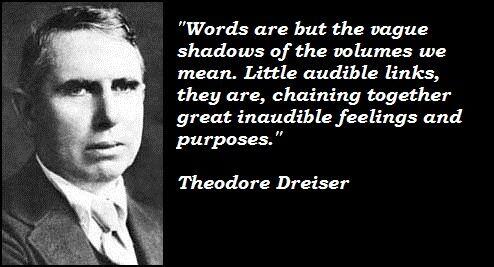

On this day in 1945 Theodore Dreiser died. Dreiser was born in Terre Haute, Indiana in 1871. The ninth child of German immigrants, Sarah and John Paul Dreiser, he experienced considerable poverty while a child and at the age of fifteen was forced to leave home in search of work.

After briefly attending Indiana University, he found work as a reporter on the Chicago Globe. Later he worked for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, the St. Louis Republic and Pittsburgh Dispatch. In his autobiography, Newspaper Days he recalls reporting a meeting addressed by Terence Powderly: "Some are silk purses and others sows' ears and cannot be made the one into the other by any accident of either poverty or wealth. Just at this time, however, after listening to Mr. Powderly (a significant man in connection with that movement) and taking notes on his speech, I came to the conclusion that all laborers had a just right to much better pay and living conditions, and in consequence had a great cause and ought to stick together - only I was not one of them." He later moved to New York City where he attempted to establish himself as a novelist. Dreiser was influenced by books by authors such as William Dean Howells, Frank Norris, Charles Edward Russell and David Graham Phillips.

Dreiser worked for the New York World before Frank Norris, who was working for Doubleday, helped Dreiser's first novel, Sister Carrie (1900), to be published. However, the owners disapproved of the novel's subject matter (the moral corruption of the heroine, Carrie Meeber) and it was not promoted and therefore sold badly.

Floyd Dell got to know Dreiser during this period: "Theodore Dreiser - a large, cumbrous, awkward, thoughtful, friendly person, with no small talk but with a great zest for serious conversation. A brave lover of the truth, and a rugged, stubborn and gallant fighter for it. I respected him deeply, and laughed at him - a combination which he found it hard to understand."

Dreiser continued to work as a journalist and as well as writing for mainstream newspapers such as the Saturday Evening Post, also had work published in socialist magazines such as the New York Call. However, unlike many of his literary friends such as Floyd Dell, Upton Sinclair, Sinclair Lewis, Max Eastman and Jack London, he never joined the American Socialist Party.

Dreiser's second novel, Jennie Gerhardt was not published until 1911. With the support of the literary critic, Floyd Dell, who considered Dreiser, a major writer, Sister Carrie was republished in 1912. Arnold Bennett was one of the many critics who praised the book and described it as the "best novel that has ever come out of America".

This was followed by two novels The Financier (1912) and The Titan (1914) about Frank Cowperwood, a power-hungry business tycoon. These books were influenced by Lawless Wealth: The Origin of Some American Fortunes, a book about the American Tobacco Trust, written by Charles Edward Russell. This was followed by The Genius (1915).

Dreiser was highly critical of the capitalist system: "In my personal judgment, America as yet certainly is neither a social nor a democratic success. Its original democratic theory does not work, or has not, and a trust - and a law-frightened people, to say nothing of a cowardly or suborned, and in case helpless, press, prove it. Where in any country not dominated by an autocracy has ever a people slipped about afraid to voice its views on war, on freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the trusts, religion - indeed, any honest private conviction that it has. In what country can a man be thoroughly browbeaten, arrested without trial, denied the privilege of a hearing and held against the written words of the nation's Constitution guaranteeing its citizens freedom of speech, of public gathering, of writing and publishing what they honestly feel? In what other lands less free are whole elements held in a caste condition - the Negro, the foreign born, the Indian?"

A group of left-wing writers including Dreisler, Floyd Dell, John Reed, George Jig Cook, Mary Heaton Vorse, Michael Gold, Susan Glaspell, Hutchins Hapgood, Harry Kemp, William Zorach, Neith Boyce and Louise Bryant, who lived in Greenwich Village, often spent their summers in Provincetown, a small seaport in Massachusetts.. In 1915 several members of the group established the Provincetown Theatre Group. A shack at the end of the fisherman's wharf was turned into a theatre. Later, other writers such as Eugene O'Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay joined the group. Many of the productions that appeared at Provincetown were later transferred to New York City. This were initially performed at an experimental theatre on MacDougal Street but some of the plays, especially by Glaspell and O'Neill were critical successes on Broadway.

Since his early days of journalism Dreiser "began to observe a certain type of crime in the United States that proved very common. It seemed to spring from the fact that almost every young person was possessed of an ingrown ambition to be somebody financially and socially." Dreiser described this as a form of disease. He added that he observed "many forms of murder for money...the young ambitious lover of some poorer girl... for a more attractive girl with money or position...it was not always possible to drop the first girl. What usually stood in the way was pregnancy."

This information inspired Dreiser's greatest novel, An American Tragedy (1925). The book was based on the Chester Gillette and Grace Brown murder case. One critic pointed out that the novel is a "story of a man struggling against social, economic, and environmental forces - as well as forces within himself - that slowly drown him in a tide of misfortune." It has been argued that the novel was an example of naturalism, an extreme form of realism, that had been inspired in part by the scientific determinism of Charles Darwin and the economic determinism of Karl Marx.

Thomas P. Riggio commented: "Although the novel was a critical and commercial success (in fact, Dreiser's only best-seller), he was not yet finished battling such literary vice crusaders as the Watch and Ward Society. The novel was banned in Boston, where the sale of the book led to a trial and an appeal that dragged on in the courts for years. This, however, was now an isolated instance. Dreiser seemed finally to have won over even his most severe critics, many of whom were now applauding the book as the Great American Novel."

Dreiser become involved in several campaigns against injustice. This included the lynching of Frank Little, one of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World, the Sacco and Vanzetti Case, the deportation of Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and Mollie Steimer, the false conviction of the trade union leader, Tom Mooney, who spent twenty-two years in prison for a crime he did not commit and the Scottsboro Case. His biographer, Jerome Loving, has argued: "Dreiser was an obstinate man. Once he set his mind to something, nothing could change it. As an adult, he also seems never to have admitted either regret or embarrassment over his actions, no matter how ridiculous or wrong-headed some of them might seem today.... His energy would go strictly to social causes, no matter how far afield they would take him from his life in literature or how unflatteringly they might cast him in the public eye."

In 1928 Dreiser wrote: "On thinking back over the books I have written, I can only say this has been my vision of life - life with its romance and cruelty, its pity and terror, its joys and anxiety, its peace and conflict. You may not like my vision but it is the only one that I have seen and felt, therefore, it is the only one I can give you." Dreiser, a socialist, wrote several non-fiction books on political issues. This included Dreiser Looks at Russia (1928) and Tragic America (1931).

Malcolm Cowley recalls that he attended a meeting in April 1931 that was addressed by Dreiser: "Dreiser stood behind a table and rapped on it with his knuckles. He unfolded a very large, very white linen handkerchief and began drawing it first through his left hand, then through his right hand, as if for reassurance of his worldly success. He mumbled something we couldn't catch and then launched into a prepared statement. Things were in a terrible state, he said, and what were we going to do about it? Nobody knew how many millions were unemployed, starving, hiding in their holes. The situation among the coal miners in Western Pennsylvania and in Harlan County, Kentucky, was a disgrace. The politicians from Hoover down and the big financiers had no idea of what was going on." Dreiser then went onto argue that "the time is ripe for American intellectuals to render some service to the American worker."

During the Great Depression Dreiser wrote: "I feel that the immense gulf between wealth and poverty in America and throughout the world should be narrowed. I feel the government should effect the welfare of all the people - not that of a given class." He became a member of the League of American Writers and was an active supporter of the Popular Front government during the Spanish Civil War. As Thomas P. Riggio pointed out: "Dreiser wrote little fiction in the 1930s. He devoted much of himself to political activities. A partial list provides an idea of the range of his social interests: he fought for a fair trial for the Scottsboro Boys, young African Americans unfairly accused of rape in Alabama; he contributed considerable time to the broadly-based political and literary reforms sponsored by the American Writer's League; he spoke out against American imperialism abroad; he attacked the abuses of the financial corporations; he went to Kentucky's Harlan coal mines, as chairman of the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, to publicize the wrongs suffered by the striking miners; he investigated the plight of tobacco farmers who were cheated by the large tobacco companies; he spoke on behalf of several antifascist organizations and attended an international peace conference in Paris; he became an advocate in America for aid to the victims of the Spanish Civil War."

Dreiser published America is Worth Saving (1941). Theodore Dreiser joined the American Communist Party in July 1945. He summed up his reasons for his decision: "Belief in the greatness and dignity of Man has been the guiding principle of my life and work. The logic of my life and work leads me therefore to apply for membership in the Community Party."

Jerome Loving, the author of The Last Titan: A Life of Theodore Dreiser (2005) has argued: "Dreiser may have also chosen to become a formal member of the party because of the harassment he had received from the FBI and what was to become the Congressional Committee for Un-American Activities. The latter was already looking askance at the movie industry for its alleged sympathies with communism."

Theodore Dreiser died on 28th December 1945. Henry L. Mencken, who had been a great supporter of Dreiser during his lifetime, argued: "No other American of his generation left so wide and handsome a mark upon the national letters. American writing, before and after his time, differed almost as much as biology before and after Darwin. He was a man of large originality, of profound feeling, and of unshakable courage. All of us who write are better off because he lived, worked, and hoped."

On this day in 1948 trade union leader, Agnes Nestor, died in Chicago. Agnes Nestor was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on 24th June, 1880. In 1807 the moved to Chicago where she went to work in a glove factory.

Nestor became an active trade unionist and in 1898 emerged as one of the leaders during a ten day strike at her factory. In 1902 she helped form the International Glove Workers Union. The following year Nestor joined with Mary Kenney O'Sullivan, Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, Margaret Haley, Helen Marot, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge to form the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL).

Over the next few years Nestor campaigned for women's suffrage, a minimum wage and maternity health legislation. She was also a strong opponent of child labour.

Nestor held several senior posts in the International Glove Workers Union, including vice president (1903-1906 and 1915-38), secretary-treasurer (1906-1913), general president (1913-1915) and director of research and education (1938-1948).

On this day in 1993 William L. Shirer died. Shirer, the son of a lawyer, was born in Chicago in 1904. When he was a child his father died and the family moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He had to deliver newspapers and sell eggs to help the family finances. After leaving school he worked on the local newspaper.

In 1925 Shirer toured Europe and while in Paris found work with the Chicago Tribune. He started on the copy desk but after learning French, German, Italian and Spanish became a foreign correspondent. In 1933 Shirer married a Viennese photographer and the following year moved to Berlin to work for Universal Service.

The historian, Sally J. Taylor, has pointed out: "On the surface, he seemed a mild-mannered, ineffectual type who wore thick spectacles and puffed away blandly on his pipe, giving an appearance completely at odds with his complicated temperament and awesome intelligence. By the time he was thirty, he had worked his way up to the position of chief of the Central European bureau of the Chicago Tribune. In the following few years, he would report from practically every major capital on the Continent, as well as locations as far flung as India and Afghanistan. Quite simply, Bill Shirer knew everybody in the newspaper business in Europe."

Edward Murrow recruited Shirer to work for Columbia Broadcasting Service in 1937. As its Berlin representative, Shirer provided a regular commentary of the developments in Nazi Germany. However, the authorities kept a close watch on Shirer and most of his broadcasts were censored. It eventually became impossible for Shirer to report accurately on the situation in Germany and he left the country in December, 1940.

Shirer's book, Berlin Diary: 1933-41, was published in 1941. Other books by Shirer on Nazi Germany include End of a Berlin Diary (1947), The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) and This Is Berlin: Reporting from Nazi Germany (1999).