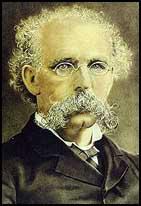

Terence Powderly

Terence Powderly, the son of Irish immigrants, was born in Carbondale, Pennsylvania on 22nd January, 1849. He worked as a machinist and joined the Knights of Labor in 1874.

Powderly advanced rapidly in the organization and in 1879 was appointed as grand master workman, the union's highest post. At that time the Knights had an estimated 10,000 members. As leader of the organisation he was instrumental in the establishment of labor bureaus and arbitration systems in a large number of states.

Powderly was also a member of the Greenback Labor Party. The party program included the coinage of silver on a par with gold, an adequate supply of money, the taxing of government bonds, a maximum eight-hour day, the introduction of graduated income tax and opposition to railroad land grants. Powderly was elected three times as mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania, serving from 1878 to 1884.

The popularity of the Knights of Labor dramatically declined following the Haymarket Bombing in Chicago on 4th May, 1886. One of those executed had been a Knight and the membership plummated after false rumours circulated claiming that the organisation had been infiltrated by anarchists.

The journalist, Theodore Dreiser, saw Powderly address a meeting during this period: "Some are silk purses and others sows' ears and cannot be made the one into the other by any accident of either poverty or wealth. Just at this time, however, after listening to Mr. Powderly (a significant man in connection with that movement) and taking notes on his speech, I came to the conclusion that all laborers had a just right to much better pay and living conditions, and in consequence had a great cause and ought to stick together - only I was not one of them."

The author of Thirty Years of Labor (1889), Powderly was appointed U.S. Commissioner General of Information (1897-1902) and head of the Division of Information in the Bureau of Immigration (1907-21). Terence Powderly died on 24th June, 1924. His autobiography, The Path I Trod (1940) was published posthumously.

Primary Sources

(1) Theodore Dreiser, Newspaper Days (1922)

Again, I attended various churches to hear sermons, interviewed the Irish boss of the city - one Edward Butler, an amazing person with a head more or less like that of a great gnome or ogre, who immediately took a great fancy to me and wanted me to come and see him again (which I did once) and who, as I discovered later, held the political fortunes of the city in his right hand. I wrote up a fire or two, a labor meeting or two, and at one of these first saw Terence V. Powderly, the head of that astounding, albeit mushroom, organization known as the Knights of Labor.

It was in a dingy hall at 9th or 10th and Walnut, a dismal region and a dismal institution known as the Workingman's Club or some such thing as that, which had a single red light hanging out over its main entrance. This long, lank leader, afterwards so much discussed in the so-called "capitalistic press," was sitting on a wretched platform surrounded by local labor leaders and about to discuss the need of closer union between all classes of labor, as he subsequently did.

In regard to all matters which related to the rights of labor and capital at this time, I was ignorant as a mongoose. Although I was a laborer myself, in a fair sense of the word, yet I was more or less out of sympathy with these individuals, not as a class struggling for their "rights" (I did not know truly, what their rights or wrongs were) but rather as individuals. I thought, I suppose - I cannot remember what I did think, but it comes back to me in this way-that they were not quite as nice as I was, not as refined and superior in their aspirations and therefore not as worthy, perhaps, or at least not destined to succeed as well as myself. I understood, or let me say felt, then dimly what subsequently and after many rough disillusionments I came to accept as a fact: that some people are born dull, others shrewd, some wise and some undisturbedly ignorant, some tender and some savage, ad infinitum. Some are silk purses and others sows' ears and cannot be made the one into the other by any accident of either poverty or wealth. Just at this time, however, after listening to Mr. Powderly (a significant man in connection with that movement) and taking notes on his speech, I came to the conclusion that all laborers had a just right to much better pay and living conditions, and in consequence had a great cause and ought to stick together - only I was not one of them. Also I concluded that Mr. Powderly was a very shrewd man and something of a hypocrite - very simple seeming and yet not so.