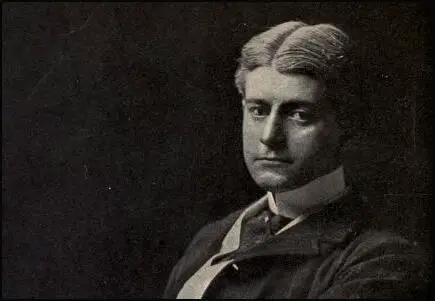

Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris was born in Chicago in 1870. At the age of 14 Norris and his family moved to San Francisco. After studying at San Francisco University (1890-94) Norris travelled to South Africa where he attempted to establish himself as a travel writer. He wrote about the Boer War for the San Francisco Chronicle but was deported from the country after being captured by the Boer Army.

Norris returned to San Francisco where he joined the staff of the magazine, The Wave. A sea story written by Norris was serialized in the magazine and was later published as a novel, Moran of the Lady Letty (1898). During this period he worked for the publishers Doubleday.

Norris continued to work as a journalist and reported the Spanish-American War for McClure's Magazine. This was followed by a couple of novels, McTeague: A Story of San Francisco (1899) and A Man's Woman (1900). Norris, who had been greatly influenced by the work of Emile Zola, also began work on a trilogy, The Epic of Wheat. The first book, The Octopus (1901), described the struggle between farming and railroad interests in California. In August 1902, Everybody's Magazine published an article by Norris, A Deal in Wheat, exposing corrupt business dealings in agriculture.

William Dean Howells was a great supporter of the work of Frank Norris: "What Norris did, not merely what he dreamed of doing, was of vaster frame, and inclusive of imaginative intentions far beyond those of the only immediate contemporary to be matched with him, while it was of as fine and firm an intellectual quality, and of as intense and fusing an emotionality. In several times and places, it has been my rare pleasure to bear witness to the excellence of what Norris had done, and the richness of his promise. The vitality of his work was so abundant, the pulse of health was so full and strong in it, that it is incredible it should not be persistent still."

Frank Norris died of peritonitis following an appendix operation on 25th October, 1902. He was only 32. He is buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California. The second book in the trilogy, The Pitt, about the manipulation of the wheat market, was published posthumously in 1903. The third part, The Wolf, was never written. Sinclair Lewis.

Also published posthumously was The Responsibility of the Novelist (1903). The book argues for naturalistic writing based on actual experience and observation. This book, and his novels, influenced a generation of writers including Upton Sinclair, who argued: "Frank Norris had a great influence upon me because I read The Octopus when I was young and knew very little about what was happening in America. He showed me a new world, and he also showed me that it could be put in a novel."

Floyd Dell was another writer who was converted to socialism by Norris' books: "Frank Norris's novel, The Octopus stirred my mind. And that spring, down in a small park near my home, I heard a man make a Socialist speech to a small and indifferent crowd. Afterwards I talked to him; he was a street-sweeper.... And my long-slumbering Socialism woke up." Other writers who claimed that they were deeply influenced by the work of Norris include David Graham Phillips, Theodore Dreiser, Charles Edward Russell and Sinclair Lewis.

Primary Sources

(1) Frank Norris, The Responsibility of the Novelist (1903)

It is not here a question of the "unarrived," the "unpublished"; these are the care-free irresponsibles whose hours are halcyon and whose endeavours have all the lure, all the recklessness of adventure. They are not recognized; they have made no standards for themselves, and if they play the saltimbanque and the charlatan nobody cares and nobody (except themselves) is affected.

But the writers in question are the successful ones who have made a public and to whom some ten, twenty or a hundred thousand people are pleased to listen. You may believe if you choose that the novelist, of all workers, is independent that he can write what he pleases, and that certainly, certainly he should never "write down to his readers" that he should never consult them at all.

On the contrary, I believe it can be proved that the successful novelist should be more than all others limited in the nature and character of his work more than all others he should be careful of what he says; more than all others he should defer to his audience; more than all others more even than the minister and the editor he should feel "his public" and watch his every word, testing carefully his every utterance, weighing with the most relentless precision his every statement; in a word, possess a sense of his responsibilities.

For the novel is the great expression of modern life. Each form of art has had its turn at reflecting and expressing its contemporaneous thought. Time was when the world looked to the architects of the castles and great cathedrals to truly reflect and embody its ideals. And the architects serious, earnest men produced such "expressions of contemporaneous thought" as the Castle of Coucy and the Church of Notre Dame. Then with other times came other customs, and the painters had their day.

The men of the Renaissance trusted Angelo and Da Vinci and Velasquez to speak for them, and trusted not in vain. Next came the age of drama. Shakespeare and Marlowe found the value of x for the life and the times in which they lived. Later on contemporary life had been so modified that neither painting, architecture nor drama was the best vehicle of expression, the day of the longer poems arrived, and Pope and Dryden spoke for their fellows...

Today is the day of the novel. In no other day and by no other vehicle is contemporaneous life so adequately expressed; and the critics of the twenty-second century, reviewing our times, striving to reconstruct our civilization, will look not to the painters, not to the architects nor dramatists, but to the novelists to find our idiosyncrasy.

I think this is true. I think if the matter could in any way be statisticized, the figures would bear out the assumption. There is no doubt the novel will in time "go out" of popular favour as irrevocably as the long poem has gone, and for the reason that it is no longer the right mode of expression.

It is interesting to speculate upon what will take its place. Certainly the coming civilization will revert to no former means of expressing its thought or its ideals. Possibly music will be the interpreter of the life of the twenty-first and twenty-second centuries...

This, however, is parenthetical and beside the mark. Remains the fact that today is the day of the novel. By this one does not mean that the novel is merely popular. If the novel was not something more than a simple diversion, a means of whiling away a dull evening, a long railway journey, it would not, believe me, remain in favour another day.

If the novel, then, is popular, it is popular with a reason, a vital, inherent reason ; that is to say, it is essential. Essential to resume once more the proposition because it expresses modern life better than architecture, better than painting, better than poetry, better than music. It is as necessary to the civilization of the twentieth century as the violin is necessary to Kubelik, as the piano is necessary to Paderewski, as the plane is necessary to the carpenter, the sledge to the blacksmith, the chisel to the mason. It is an instrument, a tool, a weapon, a vehicle. It is that thing which, in the hand of man, makes him civilized and no longer savage, because it gives him a power of durable, permanent expression. So much for the novel the instrument...

How necessary it becomes, then, for those who, by the simple art of writing, can invade the heart's heart of thousands, whose novels are received with such measureless earnestness how necessary it becomes for those who wield such power to use it rightfully. Is it not expedient to act fairly? Is it not in Heaven's name essential that the People hear, not a lie, but the Truth?

If the novel were not one of the most important factors of modern life ; if it were not the completest expression of our civilization; if its influence were not greater than all the pulpits, than all the newspapers between the oceans, it would not be so important that its message should be true.

(2) William Dean Howells, Frank Norris (1902)

The projection which death gives the work of a man against the history of his time, is the doubtful gain we have to set against the recent loss of such authors as George Douglas, the Scotchman, who wrote "The House with the Green Shutters," and Frank Norris, the American, who wrote "McTeague" and "The Octopus," and other novels, antedating and postdating the first of these, and less clearly prophesying his future than the last. The gain is doubtful, because, though their work is now freed from the cloud of question which always involves the work of a living man in the mind of the general, if his work is good (if it is bad they give it no faltering welcome), its value was already apparent to those who judge from the certainty within themselves, and not from the uncertainty without. Every one in a way knows a thing to be good, but the most have not the courage to acknowledge it, in their sophistication with canons and criterions. The many, who in the tale of the criticism are not worth minding, are immensely unworthy of the test which death alone seems to put into their power. The few, who had the test before, were ready to own that Douglas's study of Scottish temperaments offered a hope of Scottish fiction freed the Scottish sentimentality which had kept it provincial; and that Norris's two mature novels, one personal and one social, imparted the assurance of an American fiction so largely commensurate with American circumstance as to liberate it from the casual and the occasional, in which it seemed lastingly trammelled. But the parallel between the two does not hold much farther. What Norris did, not merely what he dreamed of doing, was of vaster frame, and inclusive of imaginative intentions far beyond those of the only immediate contemporary to be matched with him, while it was of as fine and firm an intellectual quality, and of as intense and fusing an emotionality.

In several times and places, it has been my rare pleasure to bear witness to the excellence of what Norris had done, and the richness of his promise. The vitality of his work was so abundant, the pulse of health was so full and strong in it, that it is incredible it should not be persistent still. The grief with which we accept such a death as his is without the consolation that we feel when we can say of some one that his life was a struggle, and that he is well out of the unequal strife, as we might say when Stephen Crane died. The physical slightness, if I may so suggest one characteristic of Crane's vibrant achievement, reflected the delicacy of energies that could be put forth only in nervous spurts, in impulses vivid and keen, but wanting in breadth and bulk of effect. Curiously enough, on the other hand, this very lyrical spirit, whose freedom was its life, was the absolute slave of reality. It was interesting to hear him defend what he had written, in obedience to his experience of things, against any change in the interest of convention. "No," he would contend, in behalf of the profanities of his people, "that is the way they talk. I have thought of that, and whether I ought to leave such things out, but if I do I am not giving the thing as I know it." He felt the constraint of those semi-savage natures, such as he depicted in "Maggie," and "George's Mother," and was forced through the fealty of his own nature to report them as they spoke no less than as they looked. When it came to "The Red Badge of Courage," where he took leave of these simple aesthetics, and lost himself in a whirl of wild guesses at the fact from the ground of insufficient witness, he made the failure which formed the break between his first and his second manner, though it was what the public counted a success, with every reason to do so from the report of the sales.

(3) Upton Sinclair, interviewed by William E. Martin (19th November, 1930)

Frank Norris had a great influence upon me because I read The Octopus when I was young and knew very little about what was happening in America. He showed me a new world, and he also showed me that it could be put in a novel.

(4) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

Frank Norris's novel, The Octopus stirred my mind. And that spring, down in a small park near my home, I heard a man make a Socialist speech to a small and indifferent crowd. Afterwards I talked to him; he was a street-sweeper. I believe William Morris has a street-sweeper Socialist in News from Nowhere; but this was not a literary echo, this Socialist street-sweeper in Quincy - he was real. And my long-slumbering Socialism woke up.