On this day on 26th January

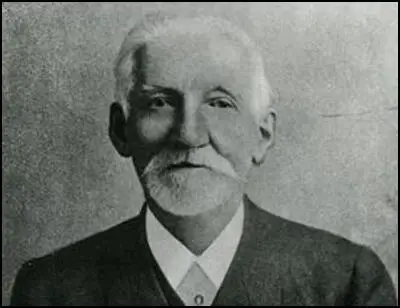

On this day in 1799 parliamentary reform martyr, Thomas Muir died. Muir, the son of a hop merchant, was born in Glasgow on 25th August 1765. He began attending Glasgow Grammar School in 1770 and at the age of ten was admitted to Glasgow University. Thomas Muir's parents were Calvinists and at their request he embarked upon the study of divinity. However, in 1782 he abandoned his studies for the Church and began attending the classes of John Millar, one of Britain's first sociologists. Millar was a republican and a supporter of parliamentary reform and had a profound influence on the development of Muir's political ideas.

In 1783 Thomas Muir became involved in a conflict with the Principal of Glasgow University when he organised a petition against the suspension of Professor John Anderson. As a result of his campaign to have Anderson reinstated, Muir was expelled from the university. With the help of Millar, Muir finished his studies at Edinburgh University and entered the Faculty of Advocates in 1787.

Muir soon developed a reputation as a lawyer who was willing to appear in court on behalf of poor clients who could not afford to pay a fee. He also became a fierce critic of a legal system that he believed was biased in favour of the rich.

The French Revolution in 1789 inspired supporters of parliamentary reform all over Britain. Young members of the Whigs in London formed the Society of the Friends of the People in April 1792. Groups were soon formed in other parts of Britain and on 26th July 1792, Thomas Muir and William Skirving established the Scottish Association of the Friends of the People. Branches were formed in Perth, Dundee, Glasgow and Edinburgh. By November there were eighty-seven branches of the Society of Friends in Britain. Thomas Muir now began to organize a General Convention of these Societies in order to develop a strategy for the achievement of parliamentary reform.

The British government became concerned about Thomas Muir and a spy was recruited to gather information about his political activities. After the spy had gathered what was considered enough evidence, Thomas Muir was arrested on 2nd January, 1793, and charged with sedition. After being interrogated for several hours he was released on bail.

Muir now travelled to London where he had talks with the leaders of the Friends of the People. The leaders of the movement were concerned about the violence taking place in France. Muir agreed to go to France and join Tom Paine in his attempts to persuade the leaders of the revolution to abandon the plan to execute Louis XVI.

Muir was unsuccessful and after having talks with the Girondist leaders, he returned to Scotland on 23rd August. The following day Muir was arrested and after being imprisoned in Edinburgh was tried for sedition before Lord Braxfield and a hand-picked jury of anti-reformers. Muir was found guilty and sentenced to fourteen years' transportation. Afraid that Scottish reformers would attempt to rescue Muir, he was quickly removed to London. Soon afterwards he was joined by other leaders of the movement, Fyshe Palmer, William Skriving and Maurice Margarot.

Radicals in the House of Commons immediately began a campaign to save the men now being described as the Scottish Martyrs. On 24th February, 1793, Richard Sheridan presented a petition to Parliament that described the men's treatment as "illegal, unjust, oppressive and unconstitutional". Charles Fox pointed out in the debate that followed that Palmer had done "no more than what had done by William Pitt (now Prime Minister of Britain) and the Duke of Richmond" when they campaigned for parliamentary reform.

Attempts to stop the men being transported failed and on 2nd May 1794, The Surprise left Portsmouth and began its 13,000 mile journey to Botany Bay. The men arrived on 25th October to join the Colony of 1,908 convicts (1362 male, 546 female). As a political prisoner, Muir was given more freedom than most convicts and he was allowed to buy a small farm close to Sydney Cove.

After two years at Port Jackson, New South Wales, Thomas Muir escaped with the help of Francis Peron, the chief mate of the American ship, the Otter of Boston. Muir reached Vancouver Island but after being offered help by a Spanish captain, he was arrested and taken on board the Ninfa. While on the way to Cadiz the Ninfa was attacked by the British warship Irresistible. During the battle Thomas Muir was hit by a glancing blow from a cannonball which smashed his left cheekbone and seriously injured both his eyes.

For several days Muir's condition was so bad he was expected to die. When the French government heard about what had happened to Muir they tried to persuade the Spanish authorities to release him. The Spanish eventually agreed and Muir arrived in Bordeaux in November 1797.

Thomas Muir joined up with Tom Paine in Paris where they continued the fight for parliamentary reform in Britain. However, Muir had never fully recovered from the wound he received on the Ninfa and his health began to deteriorate at the end of 1798. Thomas Muir was taken to Chantilly where he died on 26th January, 1799.

In 1845 Thomas Hume, the Radical MP organised the building of a 90 feet high monument in Waterloo Place, Edinburgh. It contained the following inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Erected by the Friends of Parliamentary Reform in England and Scotland." On the other side of the obelisk, based on the model of Cleopatra's Needle in London, is a quotation from a speech made by Muir on 30th August, 1793: "I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause - it shall ultimately prevail - it shall finally triumph."

On this day in 1834 trade union leader Robert Applegarth, the son of a sailor, was born in Hull. Apart from a short period as at a dame school Robert had no formal education and at the age of ten started working at a local shoemaker's shop. This was followed by other jobs where he learnt the basic skills of carpentry.

Applegarth moved to Sheffield where he met and married Mary Longmore, the daughter of a farmer. Unable to find well-paid work he moved to America. He had a variety of jobs including that of a station master. He was appalled by slavery and while in America met Frederick Douglass, one of the leaders of the emancipation movement. Confident that he could make a good living in America, he sent for his wife, but Mary was in poor health and refused to travel.

Applegarth returned to England in 1858 and was reunited with his wife in Sheffield. Soon afterwards he joined the local carpenters' union. He eventually became secretary of the branch and in 1861 agreed that the Sheffield Carpenters Union should join the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners.

The following year Robert Applegarth was elected to the full-time post of general secretary. He rented a house at 64 York Street in Lambeth which also served as the union's headquarters. Applegarth also became a leading figure in the London Trades Council. Applegarth was a strong believer in negotiated settlements and disapproved of the militant approach advocated by George Potter, the owner and editor of the trade union journal, Bee-Hive. Potter took the view that any group of men who decided to strike knew the rights and wrongs of their own case, and therefore deserved the full support of the newspaper. However, Applegarth believed that Potter was not just reporting industrial disputes but was in fact a "manufacturer of strikes".

The Bee-Hive was the official journal of the London Trades Council (LTC). As a member of the LTC executive, Applegarth investigated the Bee-Hive Potter and in 1865 he accused Potter of personal dishonesty through the maladministration of the newspaper. He also claimed that reports of a recent industrial dispute in North Staffordshire were largely inaccurate. These charges were looked at by a London Trades Council committee and as a result George Potter lost his seat on the executive and the Bee-Hive ceased to be the organisation's journal.

Applegarth's early experiences in America made him a loyal supporter of the North during the American Civil War. A proponent of universal male suffrage, he was a leading member of the Reform League and a executive member of the Labour Representation League.

When Robert Applegarth became general secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners, the union only had 1,000 members but over the next eight years it grew to over 10,000. Each member paid one shilling a week. Although the union provided generous benefits to those members who were sick or out of work by 1870, the union had accumulated funds of £17,000.

After the Sheffield Outrages in 1867 the head of the Conservative government, Earl of Derby, decided to set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions. No trade unionists were appointed but Applegarth was chosen as a union observer of the proceedings. Applegarth worked hard checking the various accusations of the employers and providing information to the two pro-union members of the Royal Commission, Frederic Harrison and Thomas Hughes. Applegarth also appeared as a witness and it was generally accepted that he was the most impressive of all the trade unionists who gave evidence before the commission.

Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and the Earl of Lichfield refused to sign the Majority Report that was hostile to trade unions and instead produced a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status. Harrison suggested several changes to the law: (1) Persons combining should not be liable for indictment for conspiracy unless their actions would be criminal if committed by a single person; (2) The common law doctrine of restraint of trade in its application to trade associations should be repealed; (3) That all legislation dealing with specifically with the activities of employers or workmen should be repealed; (4) That all trade unions should receive full and positive protection for their funds and other property.

Applegarth led the campaign to have the Minority Report accepted by the new Liberal government headed by William Gladstone. He was successful and the 1871 Trade Union Act was based largely on the Minority Report.

In 1871 Robert Applegarth became the first working man to be invited to be a member of a Royal Commission. He accepted Gladstone's offer to join the team investigating the workings of the Contagious Diseases Act. The executive of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters and Joiners objected to Applegarth working for the Royal Commission. Accused of neglected union duties, an angry Applegarth decided to resign his post as general secretary.

After his work on the Royal Commission came to an end, Applegarth found work as a commercial traveller for a French firm that had developed breathing apparatus for use in mine rescue and underwater exploration.

Applegarth also took out the English patent for the Jablochkoff Candle, an electric lighting system invented by a Russian, Paul Jablochkoff. The product was fairly successful and by 1890 he was running his own business based in Epsom. Eight years later he took up poultry farming in Bexley and introduced a new breed of hen from France.

Robert Applegarth retired to Brighton and in 1917 David Lloyd George offered to make him a Companion of Honour. He declined the offer, preferring to remain, as he wrote in his letter of refusal: "plain Robert Applegarth". He also left instructions that there should be no religious ceremony at his burial. Robert Applegarth died on 13th July 1924.

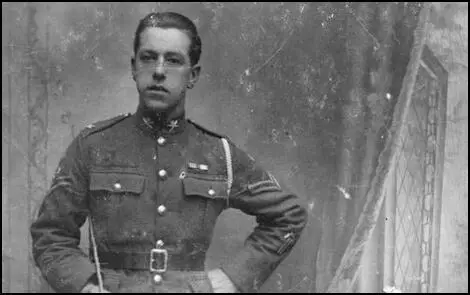

On this day in 1878 educationalist Hastings Lees-Smith, the second of the three sons of Harry Lees-Smith, a major in the Royal Artillery, and his wife, Jesse Reid Lees-Smith, was born at Murree, North-Western Provinces, India, on 26th January 1878.

On the death of his father in 1880 he was taken to England to be brought up by his grandfather, and there he was educated at Aldenham School and then at the Royal Military Academy, but as a result of "a weak constitution" he left to join Queen's College. In 1899 he graduated with second-class honours in history.

In February, 1899 Charles A. Beard and Walter Vrooman established Ruskin Hall (later known as Ruskin College), a free university offering evening and correspondence courses for working class people. The two men received most of the funds for the project from Amne Vrooman. It was named after the essayist John Ruskin (1819–1900), who had written extensively about adult education. The idea was that "economics and sociology should be taught from the working-class point of view, although not to the exclusion of the official capitalist standpoint, if that was thought desirable".

Ruskin Hall was also called a "College of the People" and the "Workman’s University". It was to be a residential institution providing study opportunities for a whole year or for shorter periods as appropriate. The residential element of the College’s work in its early years was open to men only. Harold Pollins pointed out: "It was to be part of a nationwide movement in order to cater for the large number who wanted to study but would not be able to take time off work. Provision for them, women as well as men, would be in two parts: correspondence courses, and extension classes in their own localities taught by the Ruskin Hall Faculty and by other lecturers."

Dennis Hird was appointed as the the college's first principal. Hird was a member of the Social Democratic Federation and the former rector of St John the Baptist Church, in Eastnor, who had been sacked for a lecture he gave on the subject, Jesus the Socialist (it was later published as a pamphlet that sold 70,000 copies). He had been selected by Vrooman because he was a Christian Socialist.

In addition to Hird, three other lecturers were appointed by Vrooman. Hastings Lees-Smith, who also served as vice-principal, Bertram Wilson, who became general secretary of the college, and Alfred Hacking, a friend and supporter of Hird, who was placed in charge of the correspondence students. Almost all of the students arrived on trade union scholarships worth £52.

After two years Amne Vrooman, who had divorced her husband, stopped funding Ruskin College. The general secretary of the college, was forced to seek donations from private individuals. Bertram Wilson, General Secretary of Ruskin College sent out letters explaining why they needed donations. The letters showed that the authorities were already undermining the intentions of the founders. For example, this one was written in 1907: "Madam, I hope I am doing right in bringing Ruskin College to your notice. It was founded eight years ago with the object of giving workingmen a sound practical knowledge of subjects which concern them as citizens, thus enabling them to view social questions sanely and without unworthy class bias."

Most of the people who provided the funding of the college did not share the political beliefs of Hird. Janet Vaux has argued that "Ruskin... was conceived of it as a co-operative community and labour college. Other influences on the college included academics at Oxford University who were interested in extending university education beyond the upper-class boys who were its usual customers; and many in the labour movement who saw education as a key to gaining political power."

Hastings Lees-Smith complained about the teaching of sociology as it tended to radicalize the students. Dennis Hird replied with a quote the objectives of Walter Vrooman, the founder of Ruskin College: "We shall take men who have been merely condemning our social institutions, and will teach them instead how to transform those institutions, so that in place of talking against the world, they will begin methodically and scientifically to possess the world, to refashion it, and to cooperate with the power behind evolution in making it a joyous abode of, if not a perfected humanity, at least a humanity earnestly and rationally striving towards perfection".

The students became increasingly disturbed by the economic teaching of Hastings Lees-Smith. At the time the Miners' Federation of Great Britain were attempting to negotiate with the Coal Owners Association a minimum wage for its members. Lees-Smith used his lectures to condemn this strategy on the grounds that it would cause unemployment and reduce investment. Sidney Webb, the Labour Party politician, who advocated the minimum wage, was accused of telling "a tissue of lies".

One of the students, J. M. K. MacLachlan, wrote an article for the September edition of Young Oxford (the journal of the Ruskin College students): "The present policy of Ruskin College is that of a benevolent trader sailing under a privateer flag. Professing the aims dear to all socialists, she disavows those very principles by repudiating socialism. Let Ruskin College proclaim socialism; let her convert her name from a form of contempt into a canon of respect."

In 1907 Hastings Lees-Smith was appointed professor of economics at University College, but he did not relax his grip on Ruskin. Lees-Smith was Oxford University's man at the college and so he was appointed chairman of Ruskin College's executive committee and chief adviser on studies. He now had control over staff recruitment and appointed, Charles Stanley Buxton, aged 23 as vice-principal. His father was Charles Sydney Buxton, the President of the Board of Trade, another establishment figure.

Hastings Lees-Smith also recruited Henry Sanderson Furniss to lecture on economics, who both shared his view "of the relationship between class improvement and education". Sanderson Furniss came to realise that he and Buxton were intended to carry on Lees Smith's campaign against Hird: "They were, however, ill-equipped to do so, or to provide an antidote to the Marxist ideas which Furniss criticised without knowing much about them. They knew little about teaching, and less about working-class life."

Although Dennis Hird was the Principal of Ruskin College, he was not consulted on these appointments. In 1899 his duties were defined as "to be in charge at Ruskin Hall". However, this was later changed to say all decisions were to be made by a House Committee of three, consisting of the Principal, the Vice-Principal and the General Secretary of the College. Buxton and Sanderson Furniss now joined forces to constantly outvote Hird.

In September 1907, Hastings Lees-Smith tried to marginalise Dennis Hird by proposing some new rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers. In an attempt to deal with people like Noah Ablett, William Craik and George Sims, students were forbidden to speak in public without the permission of the executive committee. It was made clear to Henry Sanderson Furniss that he was expected to try and reduce the radicalism in the college.

In November 1908, Oxford University announced that it was going to take over Ruskin College. The chancellor of the university, George Curzon, was the former Conservative Party MP and the Viceroy of India. His reactionary views were well-known and was the leader of the campaign to prevent women having the vote. Curzon visited the college where he made a speech to the students explaining the decision.

Dennis Hird replied to Curzon: "My Lord, when you speak of Ruskin College you are not referring merely to this institution here in Oxford, for this is only a branch of a great democratic movement that has its roots all over the country. To ask Ruskin College to come into closer contact with the University is to ask the great democracy whose foundation is the Labour Movement, a democracy that in the near future will come into its own, and, when it does, will bring great changes in its wake".

The author of The Burning Question of Education (1909) reported: "As he concluded, the burst of applause that emanated from the students seemed to herald the dawn of the day Dennis Hird had predicted. Without another word, Lord Curzon turned on his heel and walked out, followed by the remainder of the lecture staff, who looked far from pleased. When the report of the meeting was published in the press, the students noted that significantly enough Dennis Hird's reply was suppressed, and a few colourless remarks substituted."

William Craik, a member of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (later the National Union of Railwaymen) pointed out that his fellow students were "very perturbed at the direction in which the teaching and control of the College was moving, and by the failure of the trade union leaders to make any effort to change that direction. We new arrivals had little or no knowledge of what had been taking place at Ruskin before we got there. Most of us were socialists of one party shade or other."

New rules such as the requirement for regular essays and quarterly revision papers were introduced. "This met with strong resistance from the majority of the students, who looked upon it as one more way of making the connection with the University still closer... Most of the students had come to Ruskin College on the understanding that there would be no tests other than monthly essays set and examined by their respective tutors, and afterwards discussed in personal interviews with them."

In August 1908, Charles Stanley Buxton, the vice-principal of Ruskin College, published an article in the Cornhill Magazine. He wrote that "the necessary common bond is education in citizenship, and it is this which Ruskin College tries to give - conscious that it is only a new patch on an old garment." It has been argued that "it read as if it had been written by someone who looked upon the workers as a kind of new barbarians whom he and his like had been called upon to tame and civilise". The students were not convinced by this approach as Dennis Hird had told them about the quotation of Karl Marx: "The more the ruling class succeeds in assimilating members of the ruled class the more formidable and dangerous is its rule."

In 1909 Lord George Curzon published Principles and Methods of University Reform. In the book he pointed out that it was vitally important to control the education of future leaders of the labour movement. He urged universities to promote the growth of an elite leadership and rejected the 19th century educational reformers call for reform on utilitarian lines to encourage "upward movement" of the capitalist middle class: "We must strive to attract the best, for they will be the leaders of the upward movement... and it is of great importance that their early training should be conducted on liberal rather than on utilitarian lines."

In February, 1909, Dennis Hird was investigated in order to discover if he had "deliberately identified the college with socialism". The sub-committee reported back that Hird was not guilty of this offence but did criticise Henry Sanderson Furniss for "bias and ignorance" and recommended the appointment of another lecturer in economics, more familiar with working class views. Hastings Lees-Smith and the executive committee rejected this suggestion and in March decided to dismiss Hird for "failing to maintain discipline". He was given six months' salary (£180) in lieu of notice, plus a pension of £150 a year for life.

It is believed that 20 students were members of the Plebs League. Its leader, Noah Ablett organised a students' strike in support of Hird. The Ruskin authorities decided to close the college for a fortnight and then re-admit only students who would sign an undertaking to observe the rules. Of the 54 students at Ruskin at that time, 44 of them agreed to sign the document. However, the students decided that they would use the Plebs League and its journal, the Plebs' Magazine, to campaign for the setting up of a new and real Labour College.

Dennis Hird received very little support from other advocates of working-class education. Albert Mansbridge, the

founder of the Workers' Educational Association (WEA) in 1903, blamed Hird's preaching of socialism for his dismissal. In a letter to a French friend, he wrote "the low-down practice of Dennis Hird in playing upon the class consciousness of swollen-headed students embittered by the gorgeous panorama ever before them of an Oxford in which they have no part."

Noah Ablett took the lead in establishing an alternative to Ruskin College. He saw the need for a residential college as a cadre training school for the labour movement that was based on socialist values. George Sims, who had been expelled after his involvement in the Ruskin strike, played an important role in raising the funds for the project. On 2nd August, 1909, Ablett and Sims organised a conference that was attended by 200 trade union representatives. Dennis Hird, Walter Vrooman and Frank Lester Ward were all at the conference.

Sims explained that the "last link which bound Ruskin College to the Labour Movement had been broken, the majority of the students had taken the bold step of trying to found a new college owned and controlled by the organised Labour Movement." Ablett moved the resolution: "That this Conference of workers declares that the time has now arrived when the working class should enter the educational world to work out its own problems for itself."

The conference agreed to establish the Central Labour College (CLC). The students rented two houses in Bradmore Road in Oxford. It was decided that "two-thirds of representation on Board of Management shall be Labour organisations on the same lines as the Labour Party constitution, namely, Trade Unions, Socialist societies and Co-operative societies." Most of the original funding came from the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF) and the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR).

Hastings Lees-Smith now lost all influence over events at Ruskin College. He continued to teach at the London School of Economics (LSE). He also occupied a chair in public administration at the University of Bristol in 1909. He held this post until being elected as Liberal Party MP for Northampton in January 1910. "In parliament he soon emerged as fairly radical, supporting nationalization of certain core industries such as the railways, as well as land reform and a minimum wage for certain classes of workers".

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the Liberal government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The anti-war newspaper, The Daily News, commented: "Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken. Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption."

Hastings Lees-Smith was also opposed to the war and along with Charles Trevelyan, Morgan Philips Price, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, had discussions with Bertrand Russell and Arthur Ponsonby, who had also spoken out against the war. A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control.

Members of the UDC agreed that one of the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the Union of Democratic Control should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars.

In September 1915 Hastings Lees-Smith joined the British Army, but chose to serve in the ranks and attained the rank of corporal: this move into the forces did not make him unique among UDC members, but rather showed one of the diverse paths taken by progressive Liberals during the war. In May 1916, addressing parliament in his corporal's uniform, he opposed the introduction of conscription. He was highly critical of the government's reluctance to negotiate a peace deal with Germany.

While he was home on leave, Lees-Smith was introduced to Siegfried Sassoon by Bertrand Russell. On 30th July, 1917, Lees-Smith read out a statement against the war by Sassoon. "I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest. I believe that the purposes for which I and my fellow soldiers entered upon this war should have been so clearly stated as to have made it impossible to change them and that had this been done the objects which actuated us would now be attainable by negotiation. I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust."

Hastings Lees-Smith also claimed that an attempt had been made to keep Sassoon quiet by claiming that he was suffering from shell-shock and had been sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh. The Under-Secretary of State for War denied any such motive and that the decision was based on "health grounds and not the avoidance of publicity". Sassoon got what he wanted as his statement and Lees-Smith's comments appeared in the following morning newspapers.

In 1919 when he joined the Labour Party. In January 1920 he joined other former Liberals, such as Arthur Ponsonby and Charles Trevelyan, in publishing an appeal to former Liberals to vote against H. H. Asquith in the Paisley by-election. Lees-Smith won the Keighley seat for Labour in 1922. He wrote a number of works, of which Second Chambers in Theory and Practice (1923), which argued for an upper house elected by the House of Commons on the basis of proportional representation. He also served on the board of the New Statesman.

In the 1929 General Election the Conservatives won 8,664,000 votes, the Labour Party 8,360,000 and the Liberals 5,300,000. However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister again, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power.

In normal circumstances MacDonald would have appointed Hastings Lees-Smith to a senior position in government. However, the two men had been in dispute because of Lees-Smith's "continuing advocacy of a capital levy (wealth tax) and subsequently a surtax long after MacDonald had decided that they were electoral liabilities". Lees-Smith was appointed instead to the position of postmaster-general. In March, 1931, he was appointed as president of the Board of Education.

MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August, 1931. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

On 24th August 1931 MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

MacDonald returned to 10 Downing Street and called his final Labour Cabinet. He told them that he had changed his mind about resigning and that he agreed to form a National Government. Sidney Webb recorded in his diary: "He announced this very well, with great feeling, saying that he knew the cost, but could not refuse the King's request, that he would doubtless be denounced and ostracized, but could do no other." When the meeting was over, he asked Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey to stay behind and invited them to join the new government. All three agreed and they kept their old jobs.

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures.

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Several leading Labour figures, including Hastings Lees-Smith, Arthur Henderson, John R. Clynes, Arthur Greenwood, Charles Trevelyan, Herbert Morrison, Emanuel Shinwell, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Hugh Dalton, Susan Lawrence, William Wedgwood Benn, Tom Shaw and Margaret Bondfield lost their seats.

Following his electoral defeat, Lees-Smith returned to full-time work at the London School of Economics (LSE). He remained active in politics and in 1935 he regained Keighley and was immediately re-elected to the PLP executive. He mainly concerned with defence matters and in 1937 he was instrumental in changing the PLP's line to abstaining on, rather than voting against, the defence estimates. Hugh Dalton described him "as a first-class colleague, sensible, balanced, kindly, with no sign of bitterness, envy or egoism".

In May 1940, Hastings Lees-Smith played a leading role in bringing down Neville Chamberlain. However, Winston Churchill decided against appointing him to his coalition government. With Clement Attlee appointed to the post of deputy leader, Lees-Smith became chairman of the PLP and leader of the opposition. "The position was an important one in parliamentary terms, and Lees-Smith fulfilled it with quiet competence".

Hastings Lees-Smith died at his home, 77 Corringham Road, Golders Green, Middlesex, after a bout of influenza on 18th December 1941.

On this day in 1890 Miriam Pratt was born in Windlesham, Surrey, on 26th January 1890. Her father Charles Pratt, was a "general labourer". In about 1898 she moved to Norwich to live with her maternal aunt, Harriet and her husband, William Ward, a sergeant in the Norwich City Police. As her parents were still alive it would seem that Harriet and William had informally adopted Miriam as they had no children of their own.

Miriam went through the pupil-teacher training scheme while continuing to live with her aunt and uncle. By 1911 she was living at 7 Turner Road in Lakenham and working as an assistant teacher. Miriam also joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and would sell its newspaper, The Suffragette, on the streets of Norwich.

In 1912 Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the WSPU gave permission for her daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. Christabel knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

At a meeting in France, Christabel Pankhurst told Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When they objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property.

Miriam Pratt, a member of the WSPU, did not share these concerns. As Fern Riddell has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence."

According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest."

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. During the trial, Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone."

It has been argued that this group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks. Pratt joined the Young Hot Bloods and on 17th May 1913, she set fire to an empty building attached to the Balfour Biological Laboratory for Women, in Storey's Way, Cambridge, with paraffin-soaked cloth. The building was erected in 1884 on for the use of women studying science at Newnham and Girton. The laboratory enabled women to learn about anatomy, dissection, microbiology, zoology, chemical compounds and physics.

Fern Riddell has pointed out why Miriam selected this target: "But what good was a university laboratory, and a university education, if women were refused the right to be awarded their degrees? Although universities permitted women to attend courses and take exams, they were not allowed to graduate, and there was little opportunity for them to use the knowledge they acquired in the world outside the protected college atmosphere. Perhaps it was the unbearable unfairness of this inequality that removed any qualms Miriam and her companions might have felt that night, as they broke and set a fire that consumed a considerable amount of the adjoining building before the alarm was raised."

When the police examined the scene of the fire they found suffrage literature. This was done to show the authorities that the crime had been committed by the WSPU in protest against the government's decision not to give the vote to women. Frank Meeres has pointed out that two buildings in Cambridge had been targeted, "first a new house being built for a Mrs Spencer of Castle Street, then a new genetics laboratory. Suffrage leaflets were found in both. A lady's gold watch was discovered outside the window of the laboratory which had been used to get in.... Blood had been found where the arsonist had cut herself while scraping out the putty around the window; Miriam had a corresponding wound."

Miriam's uncle, William Ward, was involved in the investigation. He suspected the watch belonged to Miriam. When confronted by Ward about the matter she admitted that she had carried out the attack. As a result she was arrested and taken to the local police court. The Cambridge Independent Press reported that Miriam Pratt was a "tall, pretty girl", who was "dressed in a light blue corduroy coat, a blue cloth skirt, and black velvet toque trimmed with light blue ribbon."

Miriam Pratt was remanded for eight days before being granted bail. The sureties of £200 was raised by a friend, Dorothy Jewson, a member of the WSPU and the Independent Labour Party. Miriam was suspended from her job at St Paul's National School in Norwich. On 18th July, Miriam attended a protest demonstration held on Norwich Market Place against the Cat and Mouse Act.

Miriam Pratt appeared at Cambridge Assizes in October. She chose to represent herself. The main evidence against her came from her uncle. Miriam asked the judge: "Is it legal for the witness to give evidence of a statement he alleges to have obtained from me not having first cautioned me, he being a police officer?" The judge replied: "That does not disqualify him. He was not acting as a police officer." Miriam asked her uncle: "Don't you think it was your duty as a police officer to caution me?" He admitted "it was my duty, but I was speaking to you as a father would do, and I omitted to caution you."

In her final statement to the court, Miriam admitted her guilt: "I ask you to look again at what has been done and see in it not wilful and malicious damage, but a protest against a callous Government, indifferent to reasoned argument and the best interests of the country. A protest carried to extreme because no other means would avail... show by your verdict today that to fight in the cause of human freedom and human betterment is to do no wrong."

Miriam was sentenced to eighteen months' hard labour and sent to Holloway Prison. Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Miriam were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts.

Miriam Pratt immediately went on hunger strike. The damage force-feeding had inflicted on Miriam was swift and brutal. The Suffragette reported: "Lord, help and save Miriam Pratt and all those being tortured in prison for conscience sake." Doctors were worried about the impact this was having on her heart and released her and ordered three months' bed rest.

Miriam's statement in court was printed as a leaflet and distributed by members of the Women's Social and Political Union and the Independent Labour Party. This campaign, organized by Dorothy Jewson, included giving out leaflets inside Norwich Cathedral. Miriam was never recalled to prison because of the controversy created by the Cat and Mouse Act and the falling numbers of women willing to go to prison. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU was a spent force with very few active members.

On the outbreak of the First World War the WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

In October 1915, The WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. The newspaper attacked politicians and military leaders for not doing enough to win the war. In one article, Christabel Pankhurst accused Sir William Robertson, Chief of Imperial General Staff, of being "the tool and accomplice of the traitors, Grey, Asquith and Cecil". Christabel demanded the "internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores, and for a more complete and ruthless enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral."

Miriam Pratt, like her friend Dorothy Jewson, left the WSPU over its support for the war. She moved back to Norwich and on 19th May 1915 married Bernard Francis, a political activist who had been a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. At the beginning of the First World War Francis had joined the Royal Engineers and eventually reached the rank of Lieutenant.

William Ward must have forgiven Miriam because when he died in 1936 she inherited a half share of his property. Miriam moved to London where he worked as an Assistant Company Secretary. but kept in contact with her relatives in Norwich until her death at Horton Hospital in Epsom, Surrey on 24 June 1975.

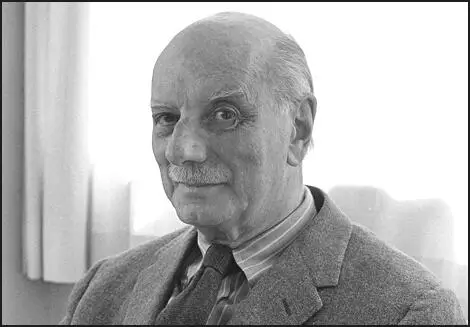

On this day in 1894 anti-fascist journalist Norman Ebbutt was born in London on 26th January 1894. His father was William Arthur Ebbutt, a journalist on the staff of the Daily News and the Daily Chronicle. His mother, Blanche Berry Ebbutt was the author of marriage advice books.

Ebbutt was educated at Willaston School in Nantwich. After leaving school in 1909 he spent the next few years in Europe learning languages. In 1914 he joined The Times but during the First World War he served as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy.

In 1925 he was sent to Berlin and in 1927 he became the newspaper's chief correspondent in Germany. He became friends with several politicians serving in the Reichstag and was a personal friend of Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, the leader of the Catholic Centre Party. As Louis L. Snyder has pointed out that "From 1930 to 1932 Brüning struggled unsuccessfully to resolve the deepening economic crisis. Unemployment rose to more than 6 million, and he was attacked bitterly by the Communists on the left and the National Socialists on the right."

In the General Election of November 1932, the Nazi Party won 196 seats. This did not give them an overall majority as the opposition also did well: Social Democratic Party (121), German Communist Party (100), Catholic Centre Party (90) and German National People's Party (52). Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor, in January 1933, but the Nazis only had a third of the seats in Parliament.

On 23rd March, 1933, the German Reichstag passed the Enabling Bill. This banned the German Communist Party and the Social Democratic Party from taking part in future election campaigns. This was followed by Nazi officials being put in charge of all local government in the provinces (7th April), trades unions being abolished, their funds taken and their leaders put in prison (2nd May), and a law passed making the Nazi Party the only legal political party in Germany (14th July).

According to his biographer, Markus Huttner: "Because of his excellent knowledge of German affairs and his long-standing contacts Ebbutt was better able than most of his fellow correspondents to cope with the serious restrictions on news gathering imposed immediately after Hitler became chancellor on 30 January 1933. As Hitler consolidated his power Ebbutt reported events with deep seriousness and dispassionate accuracy. He had a special sense for the latent antagonisms hidden behind the seemingly monolithic façade of the Führer state. In one field Ebbutt's dispatches were particularly full and reliable: for more than four years he recorded the disputes within the German protestant church and the growing tensions between confessing Christians and the Nazi regime in precise detail."

During this period he was described as "one of the foremost journalists of all time". He was a good source of information for other journalists based in Berlin: "At such times he could sit back: a man squarely built, looking out quizzically and expectantly through his thick spectacles, striking matches as he repeatedly lit his pipe, smiling delightedly when anyone made a telling point in discussion".

Douglas Reed worked with Ebbutt and considered him to be the best British journalist working in Nazi Germany: "Norman Ebbutt's dispatches were paid the greatest of all compliments - they were read by his own colleagues all over the world. A man with a profound admiration for Germany, who in pre-Hitler days was often held up by the German Press as a model foreign correspondent."

Ebbutt's problem was that his anti-Nazi views were not shared by his editor, Geoffrey Dawson, at The Times. In a 1935 speech the Prince of Wales had called for a closer understanding of Hitler in order to safeguard peace in Europe. On the suggestion of Joachim von Ribbentrop, Dawson agreed with this idea and joined Admiral Sir Barry Domvile, Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, Montague Norman, Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 7th Marquess of Londonderry, Ronald Nall-Cain, 2nd Baron Brocket, Sir Thomas Moore, Frank Cyril Tiarks, Ernest Bennett, Duncan Sandys and Norman Hulbert in forming the Anglo-German Fellowship.

Dawson was also a member of the Cliveden Set. Dawson was a regular weekend guest at Cliveden, the home of Lord Waldorf Astor and his wife, Lady Nancy Astor. Other members included Philip Henry Kerr (Lord Lothian), Edward Wood (Lord Halifax), William Montagu, 9th Duke of Manchester and Robert Brand.

As Jim Wilson, the author of Nazi Princess: Hitler, Lord Rothermere and Princess Stephanie Von Hohenlohe (2011) has pointed out: "The Astors' house parties became notorious for attracting members of aristocratic society supportive of Hitler and his policies, and for enthusiasts of appeasement. Lord Astor owned both The Observer and The Times, Geoffrey Dawson, editor of The Times, was another of Princess Stephanie's acquaintances and also regularly attended at Cliveden.The house parties were therefore fruitful occasions for Stephanie to work her brand of subtle propaganda: persuasive, clever conversation which traded heavily on her personal contacts with Hitler."

It has been claimed by Stanley Morison, the author of The History of The Times (1952) that Dawson had censored the reports sent by Norman Ebbutt. Another correspondent in the city, William Shirer commented: “The trouble for Ebbutt was that his newspaper, the most esteemed in England, would not publish much of what he reported. The Times in those days was doing its best to appease Hitler and to induce the British government to do likewise. The unpleasant truths that Ebbutt telephones nightly to London from Berlin were often kept out of the great newspaper”.

In a letter Geoffrey Dawson sent to H. G. Daniels of 23rd May 1937 he said that he did his utmost "to keep out of the paper anything that might hurt their (Nazi German) susceptibilities". Even though his articles were censored, Adolf Hitler still objected to them and in August 1937 Joseph Goebbels demanded that Ebbutt should leave the country. On 21st August he left Berlin, "seen off at the station by a large gathering of his colleagues". Ebbutt later complained "that the half-hearted support he got from his London superiors did not facilitate his difficult task in the capital of the Third Reich".

Soon after arriving back in London, Ebbutt suffered a severe stroke which left him heavily paralysed and with limited speech. Unable to write, for the next thirty-one years he was looked after by his second wife, Gladys Holms Ebburt. Norman Ebbutt died at his home in Midhurst on 17th October 1968.

On this day in 1898 George Coppard was born in Brighton. After attending Fairlight Place School he left at thirteen to work at a taxidermists.

Like many young men, Coppard volunteered to join the British Army in August, 1914. Although only sixteen, he was accepted after claimed he was three years older. He became a member of the Royal West Surrey Regiment and sent to Stoughton Barracks in Guildford for training.

Private Coppard was sent to France in June, 1915 as a member of a Vickers machine-gun unit. In September of that year he took part is the Artois-Loos offensive where the British Army suffered 50,000 casualties. The following he was involved in the Battle of the Somme.

On 17th October, 1916, Coppard was accidentally shot in the foot by one of his friends. For a while, Coppard was suspected of arranging the accident with his friend and he was sent to hospital with a label attached to his chest, SIW (Self-Inflicted Wound). Both men were eventually cleared of the charge but it was not until May, 1917, that Coppard was able to return to the Western Front. Soon afterwards, he took part in the Third Battle of Arras and in October, 1917, was promoted to the rank of corporal.

On 20th November, 1917, Coppard took part in the Battle of Cambrai. Coppard and other members of the Machine-Gun Corps followed 400 tanks across No Mans Land towards the German front-line. On the second day of the battle, Coppard was seriously wounded by a German machine-gunner. The bullet severed the femoral artery and it was only the swift action of a lance-corporal that used his boot-laces as a tourniquet that saved his life.

Discharged from the army in 1919, Coppard was unemployed for several months before becoming an assistant steward in a golf club. This was followed by periods as a warehouse clerk in Greenock, Scotland, and a waterguard officer in the Custom and Excise Department. In 1946 Coppard became an Executive Officer to the Ministry of National Insurance, a post he held until his retirement in 1962.

Coppard, who kept a diary during the First World War, decided to write an account of his experiences as a soldier on the Western Front. He sent a copy of his memoirs to the archives department of Imperial War Museum. Noble Frankland, the director of the museum, was so impressed with the manuscript that he arranged for it to have a larger audience. Coppard's book, With a Machine Gun to Cambrai was published in 1969. George Coppard died in 1984.

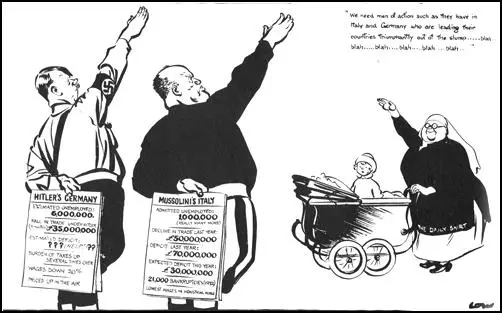

On this day in 1934 David Low produces a cartoon that suggests that the owner of the Daily Mail is a fascist. Low used his cartoons to attack those who supported Oswald Mosley, the leader of the National Union of Fascists. This included Lord Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail and Evening News. Low wrote in his autobiography: "A British Fascist Party grew up overnight; and the Daily Mail, then Britain's biggest popular newspaper, approved it. With the zest I added the first Lord Rothermere, its proprietor, to my cast of cartoon characters. He made up well in a black shirt helping to stoke the fires of class hatred. Lord Rothermere was much incensed and complained bitterly. Dog doesn't eat dog. It isn't done, said one of his Fleet Street men, as though he were giving me a moral adage instead of a thieves' wisecrack."

In January 1934, he drew a cartoon showing Rothermere as a nanny giving a Nazi salute and saying "we need men of action such as they have in Italy and Germany who are leading their countries triumphantly out of the slump... blah... blah... blah... blah." The child in the pram is saying "But what have they got in their other hands, nanny?" Hitler and Mussolini are hiding the true records of their periods in government. Hitler's card includes, "Hitler's Germany: Estimated Unemployed: 6,000,000. Fall in trade under Hitler (9 months) £35,000,000. Burden of taxes up several times over. Wages down 20%."

Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard, was a close friend and business partner of Lord Rothermere, and refused to allow the original cartoon to be published. At the time, Rothermere controlled forty-nine per cent of the shares. Low was forced to make the nanny unrecgnisable as Rothermere and had to change the name on her dress from the Daily Mail to the Daily Shirt.

Martin Walker, the author of Daily Sketches: Cartoon History of Twentieth Century Britain (1978) argues that Low was one of a couple of cartoonists in Britain who criticised Mosley and his fascist movement: "A fascist rally at Olympia, marked by the brutality of Mosley's stewards towards hecklers in the audience, began to swing public opinion in Low's direction. But in the summer of 1934, Low was almost alone in his opposition in the popular press; the Daily Mail gave Mosley regular and favourable publicity."

On this day in 1938 Eslanda Goode, the wife of Paul Robeson, wrote about visiting the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Goode wrote: "Saw lots of Negro comrades, Andrew Mitchell of Oklahoma, Oliver Ross of Baltimore, Frank Warfield ofSt Louis. All were thrilled to see us and talked at length with Paul. All the white Americans, Canadians and English troops were also thrilled to see Paul. A Major Johnson - a West Pointer - had charge of training. The officers arranged a meeting in the church and all the Brigade gathered there at 2:30 sharp, simply packing the church. But before they filed in, they passed in review in the square for us, saluting us with Salud! as they passed. Major Johnson told the men that they are to go up to the front line tomorrow. The men applauded uproariously at that news. Then Paul sang, the men shouting for the songs they wanted: 'Water Boy', 'Old Man River', 'Lonesome Road', 'Fatherland'. They stomped and applauded each song and continued to shout requests. It was altogether a huge success. Paul loved doing it. Afterwards we had twenty minutes with the men and took messages for their families."

Goode married Paul Robeson in 1921 but continued her studies and after graduating from the University of Chicago in 1923, Goode became the first African American analytical chemist at Columbia Medical Centre. Her book, Paul Robeson, Negro, was published in 1930.

Goode became increasingly concerned with the issue of civil rights. She also became close friends with the radical political figures, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. In her autobiography Goldman wrote that "Essie (Goode) was a delightful person, and Paul (Robeson) fascinated everyone."

In 1932 Goode became her Robeson's manager and was closely associated with his various political campaigns. This included opposition to fascists in Europe and attempts to persuade Congress to pass anti-lynching legislation. Goode and her husband, Paul Robeson, were both supporters of the Popular Front government in Spain. On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Goode was active in raising money for the International Brigades. In January 1938 Goode, Robeson joined Charlotte Haldane, Secretary of the Dependents Aid Committee, in Spain.

Goode studied social anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science (1936-37) and in the Soviet Union at the National Minorities Institute before publishing African Journey in 1945.

Goode and Robeson's political activities led to them being investigated by House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The government decided that both were members of the American Communist Party. Under the terms of the Internal Security Act, members of the party could not use their passports. Blacklisted at home and unable to travel abroad, Robeson's income dropped from $104,000 in 1947 to $2,000 in 1950.

Eslanda Good and Paul Robeson both opposed the Korean War and drew attention to the murders of Harriet and Harry S. Moore on 25th December, 1951, because of their attempts to establish a branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in Heartbreak Ridge in Florida. She wrote they were killed "not on Heartbreak Ridge on the distant battlefield of Korea, but on Heartbreak Ridge here in Mims, Florida." Their assassination proved, she wrote, that the world prestige of the United States was being threatened by "a few vicious, powerful active Un-Americans."

When Goode appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1955 she pointed out to the senators: "You're white and I'm a Negro, and this is a very white committee." She denied being a member of the American Communist Party but praised its policy of being in favour of racial equality.

In 1958 the government lifted the ban it had imposed prohibiting the Robesons from leaving the United States. The couple moved to Europe where they lived for five years. Eslanda Goode died of cancer in 1965.

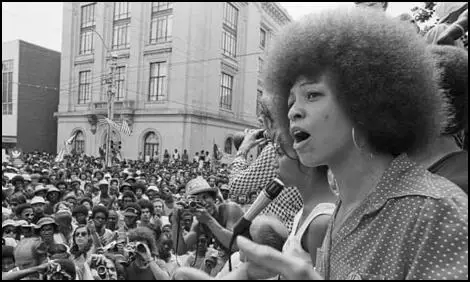

On this day in 1944 Angela Davis, the daughter of an automobile mechanic and a school teacher, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on 26th January, 1944. The area where the family lived became known as Dynamite Hill because of the large number of African American homes bombed by the Ku Klux Klan. Her mother was a civil rights campaigner and had been active in the NAACP before the organization was outlawed in Birmingham.

Davis attended segregated schools in Birmingham before moving to New York with her mother who had decided to study for a M.A. at New York University. Davis attended a progressive school in Greenwich Village where several of the teachers had been blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

In 1961 Davis went to Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts to study French. Her course included a year at the Sorbonne in Paris. Soon after arriving back in the United States she was reminded of the civil rights struggle that was taking place in Birmingham when four girls that she knew were killed in the Baptist Church Bombing in September, 1963.

After graduating from Brandeis University she spent two years at the faculty of philosophy at Johann Wolfgang von Goethe University in Frankfurt, West Germany before studying under Herbert Marcuse at the University of California. Davis was greatly influenced by Marcuse, especially his idea that it was the duty of the individual to rebel against the system.

In 1967 Davis joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party. The following year she became involved with the American Communist Party.

Davis began working as a lecturer of philosophy at the University of California in Los Angeles. When the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1970 informed her employers, the California Board of Regents, that Davis was a member of the American Communist Party, they terminated her contract.

Davis was active in the campaign to improve prison conditions. She became particularly interested in the case of George Jackson and W. L. Nolen, two African Americans who had established a chapter of the Black Panthers in California's Soledad Prison. While in California's Soledad Prison Jackson and W. L. Nolen, established a chapter of the Black Panthers. On 13th January 1970, Nolan and two other black prisoners was killed by a prison guard. A few days later the Monterey County Grand Jury ruled that the guard had committed "justifiable homicide."

When a guard was later found murdered, Jackson and two other prisoners, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, were indicted for his murder. It was claimed that Jackson had sought revenge for the killing of his friend, W. L. Nolan.

On 7th August, 1970, George Jackson's seventeen year old brother, Jonathan, burst into a Marin County courtroom with a machine-gun and after taking Judge Harold Haley as a hostage, demanded that George Jackson, John Cluchette and Fleeta Drumgo, be released from prison. Jonathan Jackson was shot and killed while he was driving away from the courthouse.

Over the next few months Jackson published two books, Letters from Prison and Soledad Brother. On 21st August, 1971, George Jackson was gunned down in the prison yard at San Quentin. He was carrying a 9mm automatic pistol and officials argued he was trying to escape from prison. It was also claimed that the gun had been smuggled into the prison by Davis.

Davis went on the run and the Federal Bureau of Investigation named her as one of its "most wanted criminals". She was arrested two months later in a New York motel but at her trial she was acquitted of all charges. However, because of her militant activities, Ronald Reagan, the Governor of California, urged that Davis should never be allowed to teach in any of the state-supported universities.

Davis worked as a lecturer of African American studies at Claremont College (1975-77) before becoming a lecturer in women's and ethnic studies at San Francisco State University. In 1979 Davis visited the Soviet Union where she was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize and made a honorary professor at Moscow State University. In 1980 and 1984 Davis was the Communist Party's vice-presidential candidate.

Books published by Davis include If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance (1971), Angela Davis: An Autobiography (1974), Women, Race and Class (1981), Women, Culture, and Politics (1989), Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1999) and Seize the Time (2020).

On this day in 1985 journalist James Cameron died. Cameron was born in Battersea, London on 17th June, 1911. His father, William Cameron, was a barrister and novelist. After leaving school he worked as an office boy for the Weekly News. He worked for newspapers in Dundee and Glasgow before joining the Daily Express in 1940.

Cameron witnessed atom bomb tests in 1946. Shocked by what he saw he became a strong opponent of the possession of these weapons and later helped form the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

In 1950 Tom Hopkinson sent Cameron and Bert Hardy to report on the Korean War for the Picture Post. While in Korea the two men produced three illustrated stories for Picture Post. This included the landing of General Douglas MacArthur and his troops at Inchon. Cameron also wrote a piece about the way that the South Koreans were treating their political prisoners. Edward G. Hulton, the owner of the magazine, considered the article to be "communist propaganda" and Hopkinson was forced to resign.

Cameron now covered world events for the News Chronicle (1952-60). Michael Foot has argued: "Cameron's genius flowed in the truly great and truly liberal News Chronicle of those times. Many contributed to the triumph: Sir Gerald Barry, his editor; Tom Baistow, his foreign editor; and Vicky, the cartoonist, soon to become the closest friend of all. His passion and his wit and his readiness to fit every incident into the worldwide scene were all part of his charm. His matchless integrity was part of it too, and yet he could wear his armour without a hint of pride or piety. He could raise journalism to the highest level of literature, like a Swift or a Hazlitt."

Cameron also wrote several books including Men of Our Time (1963), Witness in Vietnam (1966), an autobiography, Point of Departure (1967), Indian Summer: A Personal Experience of India (1974), The Making of Israel (1976) and The Best of Cameron (1983).

On this day in 1990 Lewis Mumford died. Mumford was born in Flushing, Long Island on 19th October, 1895. He grew up in New York City and developed an interest in architecture.

In 1913 Mumford published his first article in Forum Magazine. By 1919 he was reviewing for The Dial, for which he later became Associate Editor. His first book on architecture, Sticks and Stones, was published in 1924.

Mumford worked as a lecturer at the New School for Social Research (1931-35) and was a member of the League for Independent Political Action. The group, that included Archibald MacLeish and John Dewey, promoted alternatives to a capitalist system they considered to be obsolete and cruel.

Mumford was concerned with the adverse effect of technology on contemporary society and this is reflected in his books, Technics and Civilization (1934) and The Culture of Cities (1938). Other books by Mumford include The Condition of Man (1944), Green Memories, The Story of Geddes Mumford (1947), A Study of the Arts in America, 1865-1895 (1950) and The City in History (1961).