16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy and Fred Shutterworth. Tensions became high when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) became involved in a campaign to register African American to vote in Birmingham.

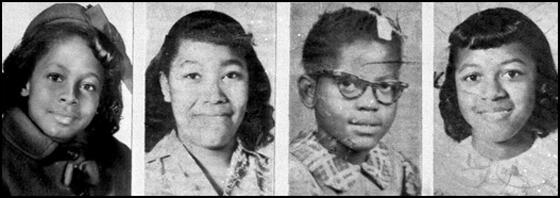

On Sunday, 15th September, 1963, a white man was seen getting out of a white and turquoise Chevrolet car and placing a box under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Soon afterwards, at 10.22 a.m., the bomb exploded killing Denise McNair (11), Addie Mae Collins (14), Carole Robertson (14) and Cynthia Wesley (14). The four girls had been attending Sunday school classes at the church. Twenty-three other people were also hurt by the blast. acquitted."

Civil rights activists blamed George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, for the killings. Only a week before the bombing he had told the New York Times that to stop integration Alabama needed a "few first-class funerals."

A witness identified Robert Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, as the man who placed the bomb under the steps of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. He was arrested and charged with murder and possessing a box of 122 sticks of dynamite without a permit. On 8th October, 1963, Chambliss was found not guilty of murder and received a hundred-dollar fine and a six-month jail sentence for having the dynamite.

The case was unsolved until Bill Baxley was elected attorney general of Alabama. He requested the original Federal Bureau of Investigation files on the case and discovered that the organization had accumulated a great deal of evidence against Chambliss that had not been used in the original trial.

In November, 1977 Chambliss was tried once again for the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. Now aged 73, Chambliss was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. Chambliss died in an Alabama prison on 29th October, 1985.

On 17th May, 2000, the FBI announced that the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing had been carried out by the Ku Klux Klan splinter group, the Cahaba Boys. It was claimed that four men, Robert Chambliss, Herman Cash, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry had been responsible for the crime. Cash was dead but Blanton and Cherry were arrested.

In May 2002 the 71 year old Bobby Cherry was convicted of the murder of Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley and was sentenced to life in prison.

Primary Sources

(1) I. F. Stone, I. F. Stone's Weekly (30th September, 1963)

It's not so much the killings as the lack of contrition. The morning after the Birmingham bombing, the Senate in its expansive fashion filled thirty-five pages of the Congressional Record with remarks on diverse matters before resuming debate on the nuclear test ban treaty. But the speeches on the bombing in Birmingham filled barely a single page. Of 100 ordinarily loquacious Senators, only four felt moved to speak. Javits of New York and Kuchel of California expressed outrage. The Majority Leader, Mansfield, also spoke up, but half his time was devoted to defending J. Edgar Hoover from charges of indifference to racial bombings. His speech was remarkable only for its inane phrasing. "There can be no excuse for an occurrence of that kind," Mansfield said of the bombing, in which four little girls at Sunday School were killed, "under any possible circumstances." Negroes might otherwise have supposed that states' rights or the doctrine of interposition or the failure of the Minister that morning to say 'Sir' to a passing white man might be regarded as a mitigating circumstance. Even so Mansfield's proposition was too radical for his Southern colleagues. Only Fulbright rose to associate himself with Mansfield's remarks and to express condemnation.

(2) Duncan Campbell, The Guardian (23rd May, 2002)

A former Ku Klux Klansman was convicted yesterday of the murder of four black girls in the 1963 church bombing in Alabama that acted as a catalyst for the civil rights movement.

Bobby Frank Cherry, 71, was convicted of first-degree murder after the jury of nine whites and three blacks had deliberated for less than a day. He will spend the rest of his life in prison.

The court found that Cherry had been one of a group of Klansmen who plotted to bomb the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which was at the centre of local civil rights protests. Two other former Klansmen have been convicted and a fourth died before facing trial.

The bomb killed Denise McNair, 11, and Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, all 14. Their deaths came days after local schools were desegregated.

During the week-long trial, relatives of the dead girls listened as some members of Cherry's own family gave evidence against him.

The former truck driver became a suspect immediately after the bombing but until 1995, when the case was reopened, it had seemed that he would escape trial. But members of Cherry's family, with whom he had fallen out, came forward to tell investigators that he had boasted of taking part in the bombing.

During the trial, his granddaughter, Teresa Stacy, told the court: "He said he helped blow up a bunch of niggers back in Birmingham." His ex-wife, Willadean Brogdon, told the court that he had confessed to her that he had lit the fuse to the dynamite that caused the explosion.

During the early 60s in Birmingham, black people were attacked by whites with little danger of facing punishment, and Cherry was active in violent attacks against civil rights activists.

He had boasted of punching the civil14 rights leader Rev Fred Shuttlesworth with knuckle dusters, saying that he had "bopped ol' Shuttlesworth in the head". He also boasted of a splitting open a black man's head with a pistol.

Cherry, who had moved to Mabank in Texas, denied involvement and pleaded not guilty, but clandestinely recorded tapes showed that he was associated with the other convicted former Klansmen, Thomas Blanton Jr and Robert "dynamite Bob" Chambliss.

Cherry had been a demolitions expert in the Marines.

The case had been closed more than three decades ago after the FBI director at the time, J Edgar Hoover, had said it would be impossible to get a guilty verdict because of the existing climate of racism.

(3) Caryl Phillips, The Guardian (18th August, 2007)

In early 1983, I was in Alabama, being driven the 130 miles from Birmingham to Tuskegee by the father of one of the four girls who had been killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing of 1963. Chris McNair is a gregarious and charismatic man who, at the time, was running for political office; he was scheduled to make a speech at the famous all-black college, Tuskegee Institute. That morning, as he was driving through the Alabama countryside, he took the opportunity to quiz me about my life and nascent career as a writer. He asked me if I had published any books yet, and I said no. But I quickly corrected myself and sheepishly admitted that my first play had just been published. When I told him the title he turned and stared at me, then he looked back to the road. "So what do you know about lynching?" I swallowed deeply and looked through the car windshield as the southern trees flashed by. I knew full well that "Strange Fruit" meant something very different in the US; in fact, something disturbingly specific in the south, particularly to African Americans. A pleasant, free-flowing conversation with my host now appeared to be shipwrecked on the rocks of cultural appropriation.

I had always assumed that Billie Holiday composed the music and lyrics to "Strange Fruit". She did not. The song began life as a poem written by Abel Meeropol, a schoolteacher who was living in the Bronx and teaching English at the De Witt Clinton High School, where his students would have included the Academy award-winning screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, the playwright Neil Simon, and the novelist and essayist James Baldwin. Meeropol was a trade union activist and a closet member of the Communist Party; his poem was first published in January 1937 as "Bitter Fruit", in a union magazine called the New York School Teacher. In common with many Jewish people in the US during this period, Meeropol was worried (with reason) about anti-semitism and chose to publish his poem under the pseudonym "Lewis Allan", the first names of his two stillborn children....

On that hot southern morning, as Chris McNair drove us through the Alabama countryside, I knew little about the background to the Billie Holiday song, and I had never heard of Lillian Smith. After a few minutes of silence, McNair began to talk to me about the history of violence against African-American people in the southern states, particularly during the era of segregation. This was a painful conversation for a man who had lost his daughter to a Ku Klux Klan bomb. I had, by then, confessed to him that my play had nothing to do with the US, with African Americans, with racial violence, or even with Billie Holiday. And, being a generous man, he had nodded patiently, and then addressed himself to my education on these matters. However, I did have some knowledge of the realities of the south - not only from my reading, but from an incident a week earlier. While I was staying at a hotel in Atlanta, a young waiter had warned me against venturing out after dark because the Klan would be rallying on Stone Mountain that evening, and after their gathering they often came downtown for some "fun". However, as the Alabama countryside continued to flash by, I understood that this was not the time to do anything other than listen to McNair.

That afternoon, in a packed hall in Tuskegee Institute, McNair began what sounded to me like a typical campaign speech. He was preaching to the converted, and a light shower of applause began to punctuate his words as he hit his oratorical stride. But then he stopped abruptly, and he announced that today, for the first time, he was going to talk about his daughter. "I don't know why, because I've never done this before. But Denise is on my mind." He studiously avoided making eye contact with me, but, seated in the front row, I felt uneasily guilty. A hush fell over the audience. "You all know who my daughter is. Denise McNair. Today she would have been 31 years old."