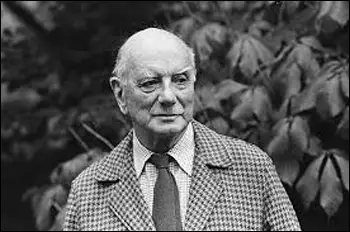

Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford was born in Flushing, Long Island on 19th October, 1895. He grew up in New York City and developed an interest in architecture.

In 1913 Mumford published his first article in Forum Magazine. By 1919 he was reviewing for The Dial, for which he later became Associate Editor. His first book on architecture, Sticks and Stones, was published in 1924.

Mumford worked as a lecturer at the New School for Social Research (1931-35) and was a member of the League for Independent Political Action. The group, that included Archibald MacLeish and John Dewey, promoted alternatives to a capitalist system they considered to be obsolete and cruel.

Mumford was concerned with the adverse effect of technology on contemporary society and this is reflected in his books, Technics and Civilization (1934) and The Culture of Cities (1938). Other books by Mumford include The Condition of Man (1944), Green Memories, The Story of Geddes Mumford (1947), A Study of the Arts in America, 1865-1895 (1950) and The City in History (1961).

In later years Mumford was awarded The Presidential Medal of Freedom (1964), the National Medal for Literature (1972) and in 1975 became an honorary knight commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Lewis Mumford died in 1990.

Primary Sources

(1) Lewis Mumford, Sticks and Stones (1924)

The leaders of modernism do not, indeed, make the mistake that some of their admirers have made: Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright's pleasure pavilions and hotels do not resemble either factories or garages or grain elevators; they represent the same tendencies, perhaps, but they do so with respect to an entirely different set of human purposes. In one important characteristic, Mr. Wright's style has turned its back upon the whole world of engineering; whereas the steel cage lends itself to the vertical skyscraper, Mr. Wright's designs are the very products of the prairie, in their low-lying, horizontal lines, in their flat roofs, while at the same time they defy the neutral gray or black or red of the engineering structure by their colors and ornament.

In sum, the best modern work does not merely respect the machine; it respects the people who use it. It is the lesser artists and architects who, unable to control and mold the products of the machine, have glorified it in its nakedness, much as the producer of musical comedies, in a similar mood of helpless adulation, has "glorified" the American girl - as if either the machine or the girl needed it.