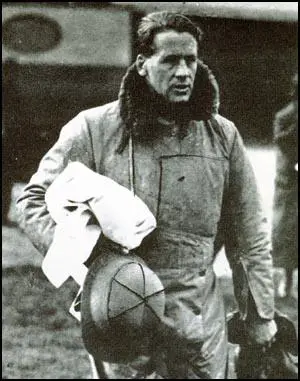

Duke of Hamilton

Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, the son of 13th Duke of Hamilton, was born in 1903. He was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford. a talented boxer he won the Scottish Amateur Middleweight title.

Douglas-Hamilton (the Marquess of Douglas and Clydesdale) joined the Royal Air Force and in 1927 he became commander of the 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron.

A member of the Conservative Party Douglas-Hamilton was elected to the House of Commons in 1930 as the representative for East Renfrewshire. In 1933 he was chief pilot on the first flight over Mount Everest. In recognition of his role in the expedition, he was decorated with the Air Force Cross in 1935.

Douglas-Hamilton was sympathetic to neo-fascist groups like the Nordic League and the Right Club. This activity was monitored by MI5 and it was reported that he had "many Nazi contacts in this country". This included Archibald Ramsay, Lord Redesdale, 5th Duke of Wellington, Duke of Westminster and the Marquess of Graham.

Albrecht Haushofer, who worked for the German Foreign Office, attended the Olympic Games in Berlin in August 1936 and made contact with several members of the House of Commons including Douglas-Hamilton, Kenneth Lindsay and Jim Wedderburn.

On 13th August, 1936, Albrecht Haushofer introduced Douglas-Hamilton to Herman Goering and General Erhard Milch, Chief of Staff of the German Air Force. During their discussion Milch told Douglas-Hamilton: "I feel we have a common enemy in Bolshevism."

In early 1937 Douglas-Hamilton wrote to Albrecht Haushofer suggesting getting together. This took place on 23rd January, in Munich. His father, Karl Haushofer, also attended the meeting where they discussed the political situation. Haushofer told Douglas-Hamilton that "Hitler understands Churchill, but he will never understand Chamberlain."

In April 1938 Haushofer visited Britain and stayed with Douglas-Hamilton at his home Dungavel House in Scotland. Douglas-Hamilton attempted to arrange for Haushofer to meet with Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary. However, Halifax was unavailable as he was on a visit to France.

On 26th June, 1938, Haushofter sent a report of his meetings with British politicians to Joachim von Ribbentrop stating that: "Britain has still not abandoned her search for chances of a settlement with Germany... A certain measure of pro-German sentiment has not yet disappeared among the British people; the Chamberlain-Halifax government sees its own future strongly tied to the achievement of a true settlement with Rome and Berlin (with a displacement of Soviet influence in Europe.)"

Adolf Hitler and Joachim von Ribbentrop had become very disillusioned with Haushofer's attempts to obtain a peace agreement with Britain and in July, 1938, he ceased to work for the government. However, he remained close to Rudolf Hess and continued to meet with those sympathetic to the Nazi government.

Albrecht Haushofer told his friend Fritz Hesse that "Hitler is now convinced that he can afford to do anything. Formerly he believed that we must have the maximum armaments because of the warlike menaces of the Powers striving to encircle us, but now he thinks that these Powers will crawl on all fours before him!" Haushofer added: "It's true that Hitler does not want war, but he is ready to risk it, and this, in my opinion, is a guarantee of disaster... We shall probably slither into the catastrophe we thought we had averted."

Haushofer continued to work behind the scenes in an attempt to persuade the British to accept a peace agreement. On 16th July, 1939, Haushofer wrote again to Douglas-Hamilton suggesting a way to avoid a war. Haushofer showed this letter to several members of the government including Winston Churchill. He replied that it was too late and that a war with Germany was inevitable.

In August 1939, a group of concentration camp prisoners were dressed in Polish uniforms, shot and then placed just inside the German border. Hitler claimed that Poland was attempting to invade Germany. On 1st September, 1939, the German Army was ordered into Poland.

Hitler, who wanted a series of localized wars, was surprised when Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. Even after it happened he found it difficult to believe that during the first few months of the war he genuinely believed that Britain would still negotiate a peace settlement.

On the outbreak of the Second World War re-enlisted and was given the rank of Air Commodore, he was responsible for air defence in Scotland and took command of the Air Training Corps.

Douglas Hamilton became the 14th Duke of Hamilton when his father died in 1940. On 8th September, 1940, Albrecht Haushofer wrote to Hamilton: "You... may find some significance in the fact that I am able to ask you whether you could find time to have a talk to me somewhere on the outskirts of Europe, perhaps in Portugal." Haushofer also refered to people who the German government believed wanted an "German-English agreement." This included Samuel Hoare and Rab Butler.

On 19th September, 1940, Haushofer wrote to Rudolf Hess about his letter to the Duke of Hamilton. He explained that Hamilton would find it difficult to fly to Portugal without the permission of Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary and Archibald Sinclair, the Secretary of State for Air. Haushofer suggested that it would probably be better to work through Samuel Hoare but planned to send the letter via an old friend.

The letter was intercepted by MI5 and Hamilton was persuaded to work as a double-agent. Hamilton agreed to go to Lisbon to meet Haushofer. Colonel Tar Robertson, head of MI5's double agent section, wrote in April 1941: "Hamilton at the beginning of the war and still is a member of the community which sincerely believes that Great Britain will be willing to make peace with Germany provided the present regime in Germany were superseded by some reasonable form of government... He is a slow-witted man, but at the same time he gets there in the end; and I feel that if he is properly schooled before leaving for Lisbon he could do a very useful job of work."

Robertson wanted Hamilton to extract "a good deal of information from Haushofer about how Germany is weathering the war". Another MI5 agent wrote that "presumably one fine day we shall be willing to listen to peace moves and I see no reason why we should not get advance knowledge if possible." However, before Hamilton's trip to Portugal could take place, Hess decided to fly a Me 110 to Scotland with the intention of having a meeting Hamilton. On 10th May, 1941, Hess arrived in Scotland. Hess hoped that Hamilton would arrange for him to meet George VI. Hess believed he could persuade the king to sack Winston Churchill and to make peace with Germany in order to join forces against the Soviet Union.

When he heard the news Adolf Hitler was quick to issue a statement pointing out that "Hess did not fly in my name." Albert Speer, who was with Hitler when he heard the news, later reported that "what bothered him was the Churchill might use the incident to pretend to Germany's allies that Hitler was extending a peace feeler."

Hess was kept in the Tower of London until being sent to face charges at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial. He was found guilty of actively supporting preparations for war and in participating in the aggression against Czechoslovakia and Poland.

After the war Hamilton was Chancellor of the University of St Andrews (1948- 1973) and President of the Air League (1959-1968). He was also director of Scottish Aviation, president of the Building Societies Association and chairman of Norwich Union Life and Fire Insurance Society.

Douglas Douglas-Hamilton died in 1973.

Primary Sources

(1) Albrecht Haushofer, letter to the Duke of Hamilton (16th July, 1938)

I have been silent for a very long time - partly from outside, partly from inside reasons. The outside reasons are easily and quickly stated: having told some very unpopular truths after my last return from England, and having pulled my full weight with the forces of moderation on our side during the weeks before Munich, I had to move very carefully afterwards. I did not want to find myself waking up one morning with an appointment as Consul General to Paramaribo (I dare say such a place exists somewhere in South America).

The inside reasons are less easily put down. But I think I can make them clear at least to you. We have had more than one talk on the Versailles Treaty and its aftermath. You know how I feel about it. I have always regarded it as a failure on the side side of British farsightedness - to put it mildly - (but you may blame the French!) that concessions and revisions mostly came too late. I fully admit that the critical years were 193I/32 One third of the concessions to Germany that you allowed to be taken later on without agreement, offered in 1932 - and Germany would never have taken the revolutionary plunge she took in 1933. But that is old history.

After the National-Socialist advent to power there remained one hope: that - after having done away with most (if not all) of the Versailles grievances by rather violent and one-sided methods -the great man of the regime would be prepared to slow down, to accept an important (though not an alldominating) position in `the Concert of Europe'. It may have been an unreasonable hope -knowing the man as we know him - but - realities being what they were - it was the only hope one could act upon. Now - I cannot entertain that hope any longer; and that is my reason for writing and posting this letter somewhere on the coast of Western Norway, where I am taking a few short weeks of rest.

I just want to give you a sign of personal friendship - I do hope that you will survive whatever may happen in Europe - and I want to send you a word of warning. To the best of my knowledge there is not yet a definite time-table for the actual explosion, but any date after the middle of August may prove to be the fatal one. So far they want to avoid the `big war'. But the one man on whom everything depends is still hoping that he may be able to get away with an isolated `local war'. He still thinks in terms of British bluff, although the Prime Minister's and Lord H's [Halifax's] last speeches have made him doubt - at least temporarily; the most dangerous thing is that he is racing against time: in more than one sense.

Economic difficulties are growing, and his own feeling (a very curious and remarkable one) that he has not a very long time of life ahead of him, is a most important factor. I could never adapt myself to the idea that any war might be inevitable; but one would have to be blind not to realise that war may be very near.

So the question: what can be done? gets all the more important. But perhaps I should have added a few things about the psychological position in the mind of the German people before trying to answer that question. On the merits of their present government, the Germans are less united than at any date since 1934. But if war breaks out on the Corridor question, they will be more solidly behind their present leader than over any case that might have led to war in these last years. The territorial solutions in the East (Corridor and Upper Silesia) have never been accepted by the German nation, and you will find many and most important Englishmen, who never thought them to be acceptable - and said so ! A war against Poland would be not unpopular.

World war of course is quite another thing: but few people in Germany realise that they would be up against a world war. I should just mention one more point: 'encirclement' has proved to be a most efficient weapon of inside propaganda. Pre-war memories (and war-blockade experiences) have risen in many minds - and the idea that England wants to `hem in' Germany on every side has got very deep into the German mind (even there, where it is not `Nazi'). Of course there are difficulties. That hateful South Alpine deal is making a big, though naturally subterranean, stir.

But war against Poland would - for the first weeks at least - unite, not disintegrate the German nation. And that is - at least to my feeling - all-important; not because I might hope that an united German nation might win the war: I am very much convinced that Germany cannot win a short war and that she cannot stand a long one - but I am thoroughly afraid that the terrific forms of modern war will make any reasonable peace impossible if they are allowed to go on for even a few months. Therefore we simply have to stop the explosion. Another European war, another Treaty of Versailles, another total revolution all over Europe - well - I need not say what it would mean for Europe as a whole.

Now to the core of the question: what can be done? Very little from inside Germany. Even now at least something from England.

Something on the tactical side: Your `inside' people know how to put a certain amount of pressure on the big man in Rome: they ought to start that pressure fairly soon. Something of the more general type: It is not enough for England to advertise herself as the big boss in the fire brigade, or to organise a fire insurance company with other nations (some of them - viz. Poland - not quite above playing with fire themselves) : What Europe needs is a real British peace plan on the basis of full equality and with considerable (but strictly mutual) safeguards on the military side. I realise to the full that a strong system of safeguards will be necessary if your people are to be persuaded to meet even the slightest German wishes regarding European or colonial territory. But as long as your Government has not lost sight of the second part of their original programme - full security and peaceful change through negotiation - they might be able to test the second part early enough to secure a positive effect. I cannot outline what might be an acceptable compromise in detail.

I cannot imagine even a short-range settlement without a change in the status of Danzig and without some sort of change in the Corridor. Possibly a long-range settlement between Germany and Poland would have to be based upon considerable territorial changes combined with population exchanges on the Greek-Turkish model (people in England mostly do not know that there are some 600,000-700,000 Germans scattered through the inner (formerly Russian) parts of Poland!) - but if there is to be a peaceful solution at all, it can only come from England and it must appear to be fair to the German public as a whole.

Even now - after the present rulers of Germany have given ample provocation - your people would be wise not to forget that they refused a plebiscitarian solution in the Corridor (and that subsequently the Poles drove some 900,000 Germans out of their former German provinces!) and that they prevented one in Upper Silesia.

(2) Report by an MI5 agent on Archibald Ramsay and the Nordic League (September, 1939)

These individuals are agreed in their hatred of Jewry and their conviction that Jews are responsible for the 'misunderstanding' between Germany and Britain, and are the instigators of the present war. There is, however, a wide range of views among them as to their own action now that the country is actually at war. Whilst very few are willing to bear arms against Germany, the majority feel that nothing should be done which might prejudice this country's interests and that they should play their part in civilian defence and humanitarian work, striving at the same time to enlighten those with whom they come into contact as to the 'real' nature of the factors which brought about the war.

Captain Ramsay MP has expressed himself as willing to continue his anti-Jewish propaganda and has enlisted the support of the above- mentioned.

He intends to proceed on two lines:

(a) The distribution among MPs; in clubs; in the Services, of a carefully prepared memorandum or leaflet aimed at refuting the Prime Minister's statement that Hitler cannot be trusted, dealing with the issues of Austria, Bohemia and Poland and designed throughout to show that World Jewry are the instigators of the war.

(b) Leaflets and adhesive labels bearing purely anti-Semitic propaganda. It is intended that these latter shall be printed secretly and distributed during the night.

Captain Ramsay has been in touch with Sir Oswald Mosley with a view to arriving at a basis for cooperation, and it is reliably reported that the two have reached agreement. In this connection two articles which appeared in the current issue (16 September) of 'Action', headed 'Peace Aims' and 'War Aims' respectively, may be significant - they are framed on very similar lines to those of Ramsay's proposed memorandum.

(3) James Leasor, Rudolf Hess: The Uninvited Envoy (1962)

"But who will you see when you reach England, if you ever do?" asked Pintsch.

"I will see the Duke of Hamilton." "Who is he?"

"He has been like me, a pioneer aviator. He shared the honour of being the first man to pilot an aeroplane over Mount Everest eight years ago, in 1933. He is a great sportsman."

"That may be, but do you know him, sir ? Have you ever met him? I am only asking these questions now because I think that if I don't someone else will later on."

"I appreciate your interest, Pintsch. Yes, I have met the Duke of Hamilton, although only briefly. We were introduced at the Olympic Games in Berlin, five years ago."

"But, sir, say you do reach England, why should the Duke of Hamilton see you again? All this is very new to me, but I just can't see it happening as you visualize. First, if you fly in uniform, presumably you will be arrested when you land-if you aren't shot down before you have the chance to land. And, if you fly in civilian clothes then you could be shot as a spy. Next, how will you ever get to see the Duke? You can't very well come down on his doorstep. You'll have to land some distance awav and then walk. You'll be picked up in no time. I'm sorry to say all this, sir, but since you have taken me so far into your confidence, I must be frank. I just cannot see how you hope to succeed."

"I appreciate your concern, Pintsch," replied Hess. "I'll try to answer your points as you made them. First, we have already gone into the question. of risks, so there's no need to bring up that point again. I'll fly in uniform for the obvious reason that you mention. But in assuming that I won't see the Duke of Hamilton, then you are being altogether too young and naive. You're proving what you have already said, that you know nothing about politics. I will see him; he will see me. You say that I can't very well land right on his doorstep ? Well, I can, and I will ! At his front door!"

Pintsch looked at Hess, amazed; he was entirely out of his depth. Was the Deputy Fuhrer of the Fatherland, the second most powerful man in the Reich-possibly in the world-going mad? Or was he insane in imagining this extraordinary conversation? Something of his bewilderment showed in his face as he dredged unsuccessfully for words.

(4) Albrecht Haushofer, report for Joachim von Ribbentrop (15th September, 1940)

On 8 September, I was summoned to Bad Godesberg to report to the Deputy of the Fuehrer on the subject discussed in this memorandum. The conversation which the two of us had alone lasted two hours. I had the opportunity to speak in all frankness.

I was immediately asked about the possibilities of making known to persons of importance in England Hitler's serious desire for peace. It was quite clear that the continuance of the war was suicidal for the white race. Even with complete peace in Europe Germany was not in a position to take over the inheritance of the Empire. The Fuehrer had not wanted to see the Empire destroyed and did not want it even today. Was there not somebody in England who was ready for peace?

First I asked for permission to discuss fundamental things. It was necessary to realise that not only Jews and Freemasons, but practically all Englishmen who mattered, regarded a treaty signed by the Fuehrer as a worthless scrap of paper. To the question as to why this was so, I referred to the ten-year term of our Polish Treaty, to the Non-Aggression Pact with Denmark signed only a year ago, to the `final' frontier demarcation of Munich. What guarantee did England have that a new treaty would not be broken again at once if it suited us? It must be realised that, even in the Anglo-Saxon world, the Fuehrer was regarded as Satan's representative on earth and had to be fought.

If the worst came to the worst, the English would rather transfer their whole Empire bit by bit to the Americans than sign a peace that left to National Socialist Germany the mastery of Europe. The present war, I was convinced, shows that Europe has become too small for its previous anarchic form of existence; it is only through close German-English co-operation that it can achieve a true federative order (based by no means merely on the police rule of a single power), while maintaining a part of its world position and having security against Soviet Russian Eurasia. France was smashed, probably for a long time to come, and we had opportunity currently to observe what Italy is capable of accomplishing. As long, however, as German-English rivalry existed, and in so far as both sides thought in terms of security, the lesson of this war was this: every German had to tell himself: we have no security as long as provision is not made that the Atlantic gateways of Europe from Gibraltar to Narvik are free of any possible blockade. That is: there must be no English fleet. Every Englishman, must, however, under the same conditions, argue: we have no security as long as anywhere within a radius of 2,000 kilometres from London there is a plane that we do not control. That is: there must be no German Air Force.

There is only one way out of this dilemma: friendship intensified to fusion, with a joint fleet, a joint air force, and joint defence of possessions in the world -just what the English are now about to conclude with the United States.

Here I was interrupted and asked why, indeed, the English were prepared to seek such a relationship with America and not with us. My reply was: because Roosevelt is a man who represents a Weltanschauung and a way of life that the Englishman thinks he understands, to which he can become accustomed, even where it does not seem to be to his liking. Perhaps he fools himself - but, at any rate, that is what he believes.

A man like Churchill - himself half-American - is convinced of this. Hitler, however, seems to the Englishman the incarnation of what he hates that he has fought against for centuries - this feeling grips the workers no less than the plutocrats.

In fact, I am of the opinion that those Englishmen who have property to lose, that is, precisely the portions of the so-called plutocracy that count, are those who would be readiest to talk peace. But even they regard a peace only as an armistice.

I was compelled to express these things so strongly because I ought not - precisely because of my long experience in attempting to effect a settlement with England in the past and my numerous English friendships - make it appear that I seriously believed in the possibility of a settlement between Adolf Hitler and England in the present stage of development.

I was thereupon asked whether I was not of the opinion that feelers had perhaps not been successful because the right language had not been used. I replied that, to be sure - if certain persons, whom we both knew well, were meant by this statement - then certainly the wrong language had been used. But at the present stage this had little significance.

I was then asked directly why all Englishmen were so opposed to Herr von Ribbentrop. I suggested that in the eyes of the English, Herr von Ribbentrop, like some other personages, played the same role as did Duff Cooper, Eden and Churchill in the eyes of the Germans. In the case of Herr von Ribbentrop, there was also the conviction, precisely in the view of Englishmen who were formerly friendly to Germany that - from completely biased motives - he had informed the Fuehrer wrongly about England and that he personally bore an unusually large share of the responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

But I again stressed the fact that the rejection of peace feelers by England was today due not so much to persons as to the fundamental outlook above.

Nevertheless, I was asked to name those whom I thought might be reached as possible contacts. I mentioned among diplomats, Minister O'Malley in Budapest, the former head of the South Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, a clever person in the higher echelons of officialdom, but perhaps without influence precisely because of his former friendliness towards Germany; Sir Samuel Hoare,t who is half-shelved and half on the watch in Madrid, whom I do not know well personally, but to whom I can at any time open a personal path; as the most promising, the Washington Ambassador Lothian, with whom I have had close personal connections for years, who as a member of the highest aristocracy and at the same time as a person of very independent mind, is perhaps best in a position to undertake a bold step - provided that he could be convinced that even a bad and uncertain peace would be better than the continuance of the war - a conviction at which he will only arrive if he convinces himself in Washington that English hopes of America are not realisable. Whether or not this is so could only be judged in Washington itself; from Germany not at all.

As the final possibility I then mentioned that of a personal meeting on neutral soil with the closest of my English friends: the young Duke of Hamilton who has access at all times to all ment - then certainly the wrong language had been used. But at the present stage this had little significance.

I was then asked directly why all Englishmen were so opposed to Herr von Ribbentrop. I suggested that in the eyes of the English, Herr von Ribbentrop, like some other personages, played the same role as did Duff Cooper, Eden and Churchill in the eyes of the Germans. In the case of Herr von Ribbentrop, there was also the conviction, precisely in the view of Englishmen who were formerly friendly to Germany that - from completely biased motives - he had informed the Fuehrer wrongly about England and that he personally bore an unusually large share of the responsibility for the outbreak of the war.

But I again stressed the fact that the rejection of peace feelers by England was today due not so much to persons as to the fundamental outlook above.

Nevertheless, I was asked to name those whom I thought might be reached as possible contacts.

I mentioned among diplomats, Minister O'Malley* in Budapest, the former head of the South Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, a clever person in the higher echelons of officialdom, but perhaps without influence precisely because of his former friendliness towards Germany; Sir Samuel Hoare,t who is half-shelved and half on the watch in Madrid, whom I do not know well personally, but to whom I can at any time open a personal path; as the most promising, the Washington Ambassador Lothian,$ with whom I have had close personal connections for years, who as a member of the highest aristocracy and at the same time as a person of very independent mind, is perhaps best in a position to undertake a bold step - provided that he could be convinced that even a bad and uncertain peace would be better than the continuance of the war - a conviction at which he will only arrive if he convinces himself in Washington that English hopes of America are not realisable. Whether or not this is so could only be judged in Washington itself; from Germany not at all.

As the final possibility I then mentioned that of a personal meeting on neutral soil with the closest of my English friends: the young Duke of Hamilton who has access at all times to all.

(5) Albrecht Haushofer, report written for Adolf Hitler (12th May, 1941)

The circle of English individuals whom I have known very well for years, and whose utilisation on behalf of a GermanEnglish understanding in the years from 1934 to i938 was the core of my activity in England, comprises the following groups and persons:

1. A leading group of younger Conservatives (many of them Scotsmen). Among them are: the Duke of Hamilton - up to the date of his father's death, Lord Clydesdale - Conservative Member of Parliament; the Parliamentary Private Secretary of Neville Chamberlain, Lord Dunglass; the present Under Secretary of State in the Air Ministry, Balfour; the present Under Secretary of State in the Ministry of Education, Lindsay (National Labour); the present Under Secretary of State in the Ministry for Scotland, Wedderburn.

Close ties link this circle with the Court. The younger brother of the Duke of Hamilton is closely related to the present Queen through his wife; the mother-in-law of the Duke of Hamilton, the Duchess of Northumberland, is the Mistress of the Robes; her brother-in-law, Lord Eustace Percy, was several times a member of the Cabinet and is still today an influential member of the Conservative Party (especially close to former Prime Minister Baldwin). There are close connections between this circle and important groups of the older Conservatives, as for example the Stanley family (Lord Derby, Oliver Stanley) and Astor (the last is owner of The Times). The young Astor, likewise a Member of Parliament, was Parliamentary Private Secretary to the former Foreign and Interior Minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, at present English Ambassador in Madrid.

I have known almost all of the persons mentioned for years and from close personal contact. The present Under Secretary of State of the Foreign Office, Butler, also belongs here; in spite of many of his public utterances he is not a follower of Churchill or Eden. Numerous connections lead from most of those named to Lord Halifax, to whom I likewise had personal access.

2. The so-called `Round Table' circle of younger imperialists (particularly colonial and Empire politicians), whose most important personage was Lord Lothian.

3. A group of the 'Ministerialdirektoren' in the Foreign Office. The most important of these were Strang, the chief of the Central European Department, and O'Malley, the chief of the South Eastern Department and afterwards Minister in Budapest.

There was hardly one of those named who was not at least occasionally in favour of a German-English understanding.

Although most of them in 1939 finally considered that war was inevitable, it was nevertheless reasonable to think of these persons if one thought the moment had come for investigating the possibility of an inclination to make peace. Therefore when the Deputy of the Fuehrer, Reich Minister Hess, asked me in the autumn of iqq.o about possibilities of gaining access to possibly reasonable Englishmen, I suggested two concrete possibilities for establishing contacts. It seemed to me that the following could be considered for this:

A. Personal contact with Lothian, Hoare, or O'Malley, all three of whom were accessible in neutral countries.

B. Contact by letter with one of my friends in England. For this purpose the Duke of Hamilton was considered in the first place, since my connection with him was so firm and personal that I could suppose he would understand a letter addressed to him even if it were formulated in very veiled language.

Reich Minister Hess decided in favour of the second possibility; I wrote a letter to the Duke of Hamilton at the end of September 1940 and its despatch to Lisbon was arranged by the Deputy Fuehrer. I did not learn whether the letter reached the addressee. The possibilities of its being lost en route from Lisbon to England are not small, after all.

(6) Colonel Tar Robertson, head of MI5's double agent section, wrote a report on the Duke of Hamilton in April 1941.

Hamilton at the beginning of the war and still is a member of the community which sincerely believes that Great Britain will be willing to make peace with Germany provided the present regime in Germany were superseded by some reasonable form of government.

This view, however, is tempered by the fact that he now considers that the only thing that this country can do is to fight the war to the finish, no matter what disaster and destruction befalls both countries. He (Duke of Hamilton) is a slow-witted man, but at the same time he gets there in the end; and I feel that if he is properly schooled before leaving for Lisbon he could do a very useful job of work.

What MI5 had in mind was to get the duke to extract "a good deal of information from Haushofer about how Germany is weathering the war," Robertson said. "

"Presumably one fine day," noted another MI5 official, "we shall be willing to listen to peace moves and I see no reason why we should not get advance knowledge if possible."

(7) Duke of Hamilton, report sent to Winston Churchill on 11th May, 1941.

The German opened by saying that he had seen me in Berlin at the Olympic Games in 1936, and that I had lunched in his house. He said, `I do not know if you recognise me, but I am Rudolf Hess.' He went on to say that he was on a mission of humanity and that the Fuehrer did not want to defeat England and wished to stop fighting. His friend Albrecht Haushofer told him that I was an Englishman who he thought would understand his (Hess's) point of view. He had consequently tried to arrange a meeting with me in Lisbon. (See Haushofer's letter to me dated September 23rd, 1940.) Hess went on to say that he had tried to fly to Dungavel and this was the fourth time he had set out, the first time being in December. On the three previous occasions he had turned back owing to bad weather. He had not attempted to make this journey during the time when Britain was gaining victories in Libya, as he thought his mission then might be interpreted as weakness, but now that Germany had gained successes in North Africa and Greece, he was glad to come.

The fact that Reich Minister Hess had come to this country in person would, he stated, show his sincerity and Germany's willingness for peace. He then went on to say that the Fuehrer was convinced that Germany would win the war, possibly soon but certainly in one, two or three years. He wanted to stop the unnecessary slaughter that would otherwise inevitably take place. He asked me if I could get together leading members of my party to talk over things with a view to making peace proposals. I replied that there was now only one party in this country. He then said he could tell me what Hitler's peace terms would be. First he would insist on an arrangement whereby our two countries would never go to war again. I questioned him as to how that arrangement could be brought about, and he replied that one of the conditions, of course, was that Britain would give up her traditional policy of always opposing the strongest power in Europe. I then told him that if we made peace now, we would be at war again certainly within two years. He asked why, to which I replied that if a peace agreement was possible, the arrangement could have been made before the war started, but since Germany chose war in preference to peace at a time when we were most anxious to preserve peace, I could put forward no hope of a peace agreement now.

He requested me to ask the King to give him `parole', as he had come unarmed and of his own free will.

He further asked me if I could inform his family that he was safe by sending a telegram to Rothacker, Hertzog Str. 17, Ziirich, stating that Alfred Horn was in good health. lie also asked that his identity should not be disclosed to the Press.