On this day on 22nd December

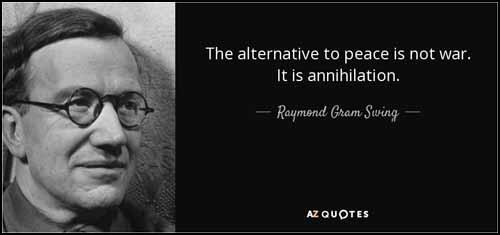

On this day in 1605 Francis Tresham died. Tresham, the eldest son of Sir John Tresham, the Sheriff of Northamptonshire, was born in about 1567. He was educated at Cambridge University but as a Roman Catholic he was unable to graduate.

In August 1581, Sir John Tresham was arrested for harbouring Catholic priests and spent the next seven years in Fleet Prison. He was also heavily fined for acts of recusancy. In 1591 Francis Tresham was also arrested and spent time in prison.

In 1596 Elizabeth I became ill. As a precautionary measure, a group of leading Roman Catholics, including Francis Tresham, Christopher Wright, Robert Catesby and John Wright were arrested and sent to the Tower of London.

Tresham was also involved with Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, in the failed attempt to remove Elizabeth I from power in 1601. Due to the minor role he played in the rebellion he was not executed and instead spent time in prison.

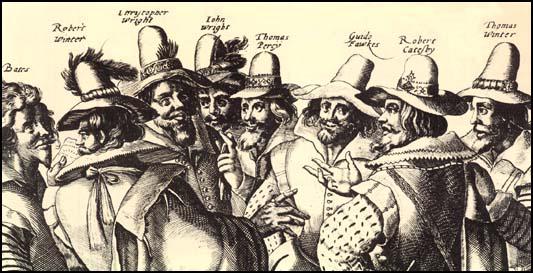

In 1605 Robert Catesby devised the Gunpowder Plot, a scheme to kill James and as many Members of Parliament as possible. Catesby planned to make the king's young daughter, Elizabeth, queen. In time, Catesby hoped to arrange Elizabeth's marriage to a Catholic nobleman. Catesby recruited Francis Tresham to join the conspiracy.

Catesby's plan involved blowing up the Houses of Parliament on 5 November. This date was chosen because the king was due to open Parliament on that day. At first the group tried to tunnel under Parliament. This plan changed when a member of the group was able to hire a cellar under the House of Lords. The plotters then filled the cellar with barrels of gunpowder. Guy Fawkes was given the task of creating the explosion.

Francis Tresham was worried that the explosion would kill his friend and brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle. On 26th October, Tresham sent Lord Monteagle a letter warning him not to attend Parliament on 5th November.

Monteagle became suspicious and passed the letter to Robert Cecil, the king's chief minister. Cecil quickly organised a thorough search of the Houses of Parliament. While searching the cellars below the House of Lords they found the gunpowder and Guy Fawkes. He was tortured and he eventually gave the names of his fellow conspirators.

Francis Tresham was arrested on 12th November. He wrote a full confession about his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot. However, many people believed he was working as a double agent for Robert Cecil.

Francis Tresham died in the Tower of London on 22nd December, 1605. Officially death was caused by a blockage of the urinary tract. However, rumours circulated that he had been poisoned by Lord Monteagle.

On this day in 1864 Marion Wallace-Dunlop, was born. Marion Wallace-Dunlop, the daughter of Robert Henry Wallace-Dunlop, of the Bengal civil service, was born at Leys Castle, Inverness, on 22nd December 1864. She later claimed that she was a direct descendant of the mother of William Wallace.

Wallace-Dunlop studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and in 1899 illustrated in art nouveau style two books, Fairies, Elves, and Flower Babies and The Magic Fruit Garden. She also exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1903, 1905 and 1906.

The art critic, Joseph Lennon, has argued: "Wallace-Dunlop’s art and writings, along with her prints, sketches, letters and photos, provide a more complete genealogy of the hunger strike, and show a woman challenging the aesthetic and gender boundaries of her day. Her oil portrait of her sister Constance (Miss C. W. D., 1892) portrays a woman with a shawl wrapped around her shoulders, who sits erect, alarmed, with a tinge of fear, and stares disturbingly out at the viewer. Meeting and challenging our own gaze, her haunted stare makes us feel we have stumbled into a private space, the subject’s own. Wallace-Dunlop had a talent for creating such unsettling images."

Wallace-Dunlop was a supporter of women's suffrage and in 1900 she joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. She was also a socialist and from 1906 she was an active member of the Fabian Women's Group. By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. Emily Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), advocated a new strategy to obtain the publicity that she thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote. As her biographer, Leah Leneman, points out, "militancy made an immediate appeal to her."

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison. The following month Wallace-Dunlop was arrested and charged with "obstruction" and was briefly imprisoned.

While in prison she came into contact with two women who had been found guilty of killing children. She wrote in her diary: "It made me feel frantic to realize how terrible is a social system where life is so hard for the girls that they have to sell themselves or starve. Then when they become mothers the child is not only a terrible added burden, but their very motherhood bids them to kill it and save it from a life of starvation, neglect. I begin to feel I must be dreaming that this prison life can’t be real. That it is impossible that it is true and I am in the midst of it. I know now the meaning of the screened galley in the Chapel, the poor condemned girl sits there with a wardress."

On her release she made a speech about the plight of the working-class: "In this country every year 120,000 babies die before they are a year old, and most of these die because of the conditions into which they are born. It is not so much the babies who die that one pities but those who survive, poor, maimed, starved, stunted little beings."

On 25th June 1909 Wallace-Dunlop was charged "with wilfully damaging the stone work of St. Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp, doing damage to the value of 10s." According to a report in The Times Wallace-Dunlop printed a notice that read: "Women's Deputation. June 29. Bill of Rights. It is the right of the subjects to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitionings are illegal."

Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. On 5th July, 1909 she petitioned the governor of Holloway Prison: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; and as a matter of principle, not only for my own sake but for the sake of others who may come after me, I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction.”

In her book, Unshackled (1959) Christabel Pankhurst claimed: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence wrote to Wallace-Dunlop: "Nothing has moved me so much - stirred me to the depths of my being - as your heroic action. The power of the human spirit is to me the most sublime thing in life - that compared with which all ordinary things sink into insignificance." He also congratulated her for "finding a new way of insisting upon the proper status of political prisoners, and of the resourcefulness and energy in the face of difficulties that marked the true Suffragette."

Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), has pointed out: "As with all the weapons employed by the WSPU, its first use sprang directly from the decision of a sole protagonist; there was never any suggestion that the hunger strike was used on this first occasion by direction from Clement's Inn."

Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike. In one eighteen month period, Emily Pankhurst, who was now in her fifties, endured ten of these hunger-strikes.

Wallace-Dunlop visited Eagle House near Batheaston in June 1910 with Margaret Haig Thomas. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Tsuga Mertensiana, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. Mary's mother, Emily Blathwayt, commented in her diary: "Miss Wallace Dunlop and Miss Haig (like so many of them) never eat meat and not much animal food at all... We liked her very much, she was so ladylike."

Wallace-Dunlop joined forces with Edith Downing to organise a series of spectacular WSPU processions. The most impressive of these was the Woman's Coronation Procession on 17th June 1911. Flora Drummond led off on horseback with Charlotte Marsh as colour-bearer on foot behind her. She was followed by Marjorie Annan Bryce in armour as Joan of Arc.

The art historian, Lisa Tickner, described the event in her book The Spectacle of Women (1987): "The whole procession gathered itself up and swung along Northumberland Avenue to the strains of Ethel Smyth's March of the Women... The mobilisation of 700 prisoners (or their proxies) dressed in white, with pennons fluttering from their glittering lances, was, as the Daily Mail observed, "a stroke of genius". As The Daily News reported: "Those who dominate the movement have a sense of the dramatic. They know that whereas the sight of one woman struggling with policemen is either comic or miserably pathetic, the imprisonment of dozens is a splendid advertisement."

Marion Wallace-Dunlop ceased to be active in the WSPU after 1911. During the First World War she was visited by Mary Sheepshanks at her home at Peaslake, Surrey. Sheepshanks later commented: "We found her in a delicious cottage with a little chicken and goat farm, an adopted baby of 18 months, and a perfectly lovely young girl who did some bare foot dancing for us in the barn; we finished up with home made honey."

In 1928 Wallace-Dunlop was a pallbearer at the funeral of Emmeline Pankhurst. Over the next few years she took care of Mrs Pankhurst's adopted daughter, Mary. Joseph Lennon has pointed out: "Wallace-Dunlop never married, but there is no evidence of any sexual relationships with either men or women, despite her many close friendships with the latter."

Marion Wallace-Dunlop died on 12th September 1942 at the Mount Alvernia Nursing Home, Guildford.

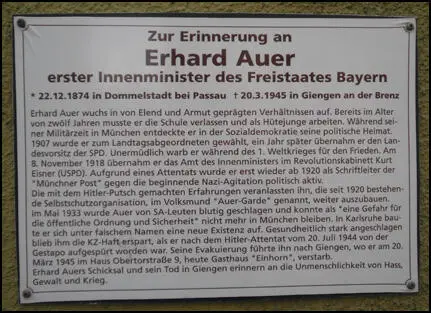

On this day in 1874 Erhard Auer, the illegitimate son of a seamstress, was born in Dommelstadl. At the age of twelve he became a farm labourer. Three years later he helped form a trade union that was immediately suppressed. In 1892 he joined the Social Democrat Party (SDP).

In 1896 he became a messenger at a trading house in Munich. Auer made rapid progress and eventually became a manager. This was followed by a managerial position in an insurance company. In 1907 Auer was elected to the Bavarian Parliament.

On the outbreak of the First World War, the SDP leader, Friedrich Ebert, ordered members in the Reichstag to support the war effort. Auer supported this policy. Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the war. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Many on the left questioned Ebert's policy when documents were published suggesting that Wilhelm II was responsible for starting the conflict. In April 1917 left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party formed the Independent Socialist Party. Members included Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Breitscheild, Julius Leber, Ernst Thälmann and Rudolf Hilferding. Several members were arrested before being released during the General Amnesty in October, 1918.

On 28th October, 1918, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany.

Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party in Munich, called for a general strike. As Paul Frölich has pointed out: "They (Eisner and his political supporters) were enthusiastic about the idea of the political strike especially because they regarded it as a weapon which could take the place of barricade-fighting, and it seemed a peaceable weapon into the bargain."

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralyzed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind."

Eisner led the large crowd into the local parliament building, where he made a speech where he declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. Eisner explained that his program would be based on democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a republic.

On 9th November, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and the Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy.

During this period Erhard Auer remained loyal to Ebert and was appointed as Minister of Interior. In 1919 he survived an assassination attempt. After his recovery he became chairman of the SPD parliamentary group. He was also active in Munich and was one of the most important figures in resisting the Nazi Party during the Munich Putsch in 1923.

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Erhard Auer, was arrested and was sent to Dachau Concentration Camp, where he died or was executed on 20th March 1945.

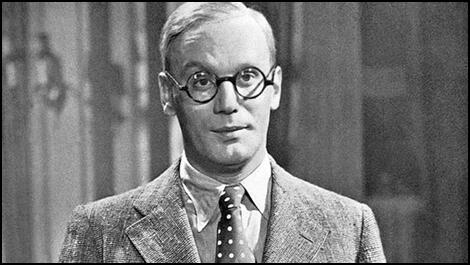

On this day in 1899 Gustaf Gründgens, the son of a prosperous businessman, was born in Düsseldorf. He served in the German Army during the First World War. After demobilization Gründgens attended acting school. According to Stefan Steinberg: "As a young man Gründgens was determined to make a name for himself. At 18 he sent a postcard to a friend advising the latter to hold on to the item because one day he, Gründgens, would be famous and the card would be valuable".

Gustaf Gründgens formed an experimental theater troupe, the Laienbund Deutscher Mimiker. Other members included Klaus Mann, Erika Mann, and Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the playwright Frank Wedekind. In 1924 Klaus wrote Anja and Esther, a play about "a neurotic quartet of four boys and girls" who "were madly in love with each other".

Gründgens decided to direct the play with himself in one of the male roles, Klaus in the other; Erika and Pamela Wedekind would be the two young women. "Klaus planned to marry Pamela, with whom Erika fell in love, while Erika arranged to marry Gustaf, with whom Klaus began an affair."

The play, which opened in Hamburg in October 1925, attracted vast amounts of publicity, partly because of its scandalous content and partly because it starred three children of two famous writers. A photograph appeared on the cover of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. It created a great deal of controversy as "Klaus's lipstick gave him the look of a transvestite".

On 24th July, 1926, Gustaf Gründgens, married Erika Mann, even though both were gay. The marriage was not successful and in 1927, she and Klaus traveled around the world. (5) Andrea Weiss, the author of In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain: The Erika and Klaus Mann Story (2008) has explained why the marriage failed: "A cynical explanation would point out that Erika’s theatrical career had flourished to the point where she no longer needed Gustaf as stepping-stone; that Gustaf had finally realised his marriage to Erika would not bestow on him her father’s impeccable social credentials."

During this period Gründgens, like Erika and Klaus, were left-wing activists, and associated with members of the German Communist Party (KPD). In 1926 he talked about creating a "Revolutionary Theatre" and Klaus claims that he was "always ready to exchange a clenched-fist welcome on his way to rehearsals". At the same time Gründgens did not hide his abhorrence for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.

Gründgens went to work for Germany's most prominent director Max Reinhardt. In 1932 he had his first opportunity to play the role with which he was to become closely identified - Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust. Later that year he voted for the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and was known "to help gay friends, colleagues and left Jewish acquaintances".

Gründgens was out of the country when Adolf Hitler came to power in early 1933. As his biographer has pointed out: "We have no way of knowing what went through his head. We do know that he was apprehensive about returning to Germany. He had not, after all, made his feelings about the Nazis a secret and he was wise enough to know that he could also encounter problems as someone, despite his short-lived marriage, known to be a homosexual."

Gustaf Gründgens did go back and he received the patronage of Hermann Göring. He was appointed the artistic director of the Prussian State Theatre and was later became a member of the Prussian state council. He was also director of Berlin's principal theatre, the Staatstheater. In 1934, his lawyer, a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA), arranged for Gründgens to move into a luxurious villa owned by a Jewish banker who had fled the country. Erika Mann, his former wife, suggested that Hitler had treated Gründgens well because of his sexuality: "Hitler's interest in him is interpreted as erotic."

Joseph Goebbels was openly hostile to him, as he was to all homosexuals (whom he referred to as 175ers according to the appropriate clause of the Weimar Constitution), but Gründgens was protected by Hitler and Göring. In 1936 Gründgens sealed a deal securing an annual average income of Reichsmark 200,000. Gründgens also starred in several propaganda films during this period earning on average RM80,000 per picture. In comparison a state secretary in Nazi Germany earned on average RM20,000. One critic claimed that "Gründgens is emblematic of the intellectual who chooses ego and career, even in the service of monsters, over principle."

Gründgens's wife, Erika Mann, like many on the left, had been forced to flee Nazi Germany. So had his brother-in-law, Klaus Mann, who was living in Amsterdam. Klaus wrote to his mother that his publisher, Fritz Helmut Landshoff, had made him a "relatively generous offer", where he was to receive a monthly wage to write a novel. Klaus originally intended to write a utopian novel about Europe in the 22nd century. The author Hermann Kesten suggested that he write a novel about a homosexual who is willing to compromise his ideals in order to have a successful career under Hitler.

Klaus accepted his advice and based his novel on Gustaf Gründgens. The novel, Mephisto (1936), portrays an actor Hendrik Höfgen (Gustaf Gründgens), who in his youth was a communist. However, unlike, Gründgens, he is not homosexual as Klaus was himself gay. He decided to use "negroid masochism" as the main character's sexual preference. In 1933, when Hitler gains power, he flees to Paris, because he expects to be persecuted for his left-wing activities. However, he is persuaded to return to Germany and takes the role of Mephisto. There are situations where Höfgen tries to help his friends or to complain about concentration camps, but he is always concerned not to lose his Nazi patrons.

In September,1944 Goebbels issued an order closing all German theatres until the end of the war. All available artistic personal were assigned to vital war production. However, Gründgens was allowed to sit out the rest of the war in his Berlin home. In April 1945 he was captured by the Red Army but eventually he was released and allowed to use his theatre talents in East Germany. In 1946 he managed to move to West Germany and over the next few years established himself as the best known actor-director in the country.

Klaus Mann, who was now living in Los Angeles, attempted to get Mephisto published in Germany. In April, 1949, he received a letter from his publisher to say that his novel could not be published in the country because of the objections of Gustaf Gründgens. Klaus wrote to Erika Mann about his problems with his publisher and his financial difficulties. "I have been luck with my family. One cannot be entirely lonely if one belongs to something and is part of it." Klaus Mann died in of an overdose of sleeping pills on 21st May 1949.

Gustaf Gründgens remained in great demand as an actor-director until he died of an an overdose of sleeping tablets while on holiday in Manila on 7th October, 1963.

On this day in 1905 Thomas Flowers, the son of John Thomas Flowers, bricklayer, and his wife, Mabel Richardson Flowers, was born at 160 Abbott Road, Poplar, London, on 22nd December, 1905. He always loved making things and when his sister was born in 1910, he "complained at the time that he would have preferred a Meccano set".

Flowers gained a scholarship that enabled him to attend technical college until he was sixteen. in 1921 he started a four-year mechanical apprenticeship at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich, while at the same time he attended evening classes, gaining a London University degree in engineering.

In 1926 Flowers joined the Post Office as an electrical engineer, and in 1930 he moved to the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill. The station was dedicated mainly to research in telecommunications and was responsible for the development of the Trans-Atlantic telephone cable. As Alan Hodges has pointed out: "His major research interest over the years had been long distance signalling, and in particular the problem of transmitting control signals, so enabling human operators to be replaced by automatic switching equipment. Even at this early date he had considerable experience of electronics, having started research on the use of electronic valves for telephone switching in 1931. This work had resulted in an experimental toll dialling circuit which was certainly operational in 1935."

On 31st August 1935 Flowers married Eileen Green. Over the next few years the couple had two sons, Kenneth and John. In the late 1930s Tommy Flowers built up considerable experience and expertise in the use of valves, in particular developing systems of valve amplifiers and switches that by 1939 enabled long-distance calls to be made without the intervention of an operator.

In February 1941, Gordon Radley, the director of the Post Office Research Station was contacted by officials of Bletchley Park, the government's codebreaking establishment. Alan Turing wanted help in building a decoder for a machine he had designed to decipher messages sent by the German military during the Second World War. Turing was put in contact with Tommy Flowers. Although the decoder project was abandoned, Turing was impressed with Flowers's work, and in February 1943 introduced him to Max Newman, who had been given the problem of dealing with the Lorenz SZ machine that was used to encrypt communications between Adolf Hitler and his generals.

The Lorenz SZ operated in a similar way to the Enigma Machine, but was far more complicated, and it provided the Bletchley codebreakers with an even greater challenge. It used a 32-letter Baudot alphabet. "While Enigma machines were capable of 159 trillion settings, the number of the combinations possible with the Lorenz SZ was estimated at 5,429,503,678,976 times greater."

Newman came up with a way to mechanise the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher and therefore to speed up the search for wheel settings. (5) Flowers later explained the objective of Newman's machine: "The purpose was to find out what the positions of the code wheels were at the beginning of the message and it did that by trying all the possible combinations and there were billions of them. It tried all the combinations, which processing at 5,000 characters a second could be done in about half an hour. So then having found the starting positions of the cipher wheels you could decode the message."

The initial machine designed by Max Newman kept on breaking down. Flowers later recalled: "I was brought in to to make it work, but I very soon came to the conclusion that it would never work. It was dependent on paper tape being driven at very high speed by means of spiked wheels and the paper wouldn't stand up to it." Flowers suggested that Newman used valves instead of the old-fashioned electromechanical relay switches that had been used in Turing's machines. He claimed valves would do the same job much faster without the need for the synchronisation of the two tapes.

Gordon Welchman, a colleague at Bletchley Park, pointed out: "Flowers seems to have realized at once that synchronization 44 punched-tape operations need not depend on the mechanical process of using sprocket holes. He used photoelectric sensing, and at that early date he had enough confidence in the reliability of switching networks based on electronic valves (tubes, in America), rather than electromagnetic relays, to risk using such techniques on a grand scale. From his prewar experience, Flowers knew that most valve failures occurred when, or shortly after, power was switched on, and he designed his equipment with this in mind. He proposed a machine using 1,500 valves."

Thomas Flowers claimed that Newman and his team of codebreakers were highly sceptical of his suggestion: "They wouldn't believe it. They were quite convinced that valves were very unreliable. This was based on their experience of radio equipment which was carted around, dumped around, switched on and off, and generally mishandled. But I'd introduced valves into telephone equipment in large numbers before the war and I knew that if you never moved them and never switched them off they would go on forever. They asked me how long it would take to produce the first machine. I said at least a year and they said that was terrible. They thought in a year the war could be over and Hitler could have won it so they didn't take up my idea."

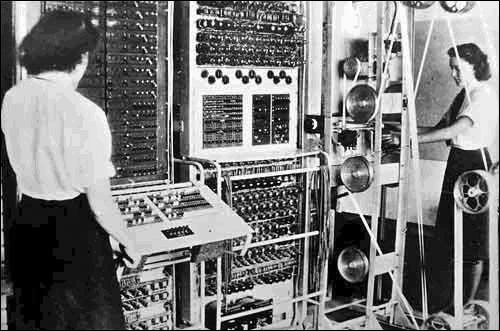

The project was now shelved. However, Flowers was so convinced that he could get Newman machine to work effectively he continued building the machine. At the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill Flowers took Newman's blueprint and spent ten months turning it into the Colossus Computer, which he delivered to Bletchley Park on 8th December 1943, but was not fully operational until 5th February 1944. It consisted of 1,500 electronic valves, which were considerably faster than the relay switches used in Turing's machine. However, as Simon Singh, the author of The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) has pointed out than "more important than Colossus's speed was the fact that it was programmable. It was this fact that made Colossus the precursor to the modern digital computer."

Newman's staff that operated the Colossus consisted of about twenty cryptanalysts, about six engineers, and 273 Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Jack Good was one of the cryptanalysts working under Newman: "The machine was programmed largely by plugboards. It read the tape at 5,000 characters per second... The first Colossus had 1,500 valves, which was probably far more than for any electronic machine previously used for any purpose. This was one reason why many people did not expect Colossus to work. But it began producing results also immediately. Most of the failures of valves were caused by switching the machine on and off."

Harry Fensom later reported: "The Colossi were of course very large, hence their name, and gave off a lot of heat, ducts above them taking some of this away. However, we appreciated this on the cold winter nights, especially about two or three in the morning. When I came in out of the rain, I used to hang my raincoat on the chair in front of the hundreds of valves forming the rotor wheels and it soon dried off. Of course it was essential that the machines were never switched off, both to avoid damaging the valves and to ensure no loss of code-breaking time. So there was an emergency mains supply in the adjoining bay which took over automatically on mains failure."

In February, 1944, the Lorenz SZ40 machine was further modified in an attempt to prevent the British from decyphering it. With the invasion of Europe known to be imminent, it was a crucial period for the codebreakers, as it was vitally important for Berlin to break the code being used between Adolf Hitler in Berlin and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Army in western Europe.

Tommy Flowers and Max Newman now began working on a more advanced computer, Colossus Mark II. Flowers later recalled: "We were told if we couldn't make the machine work by June 1st it would be too late to be of use. So we assumed that that was going to be D-Day, which was supposed to be a secret." The first of these machines went into service at Bletchley Park on 1st June 1944. It had 2,400 valves and could process the tapes five times as fast. "The effective speed of sensing and processing the five-bit characters on punched paper tape was now twenty-five thousand characters per second... Flowers had introduced one of the fundamental principles of the postwar digital computer - use of a clock pulse to synchronize all the operations of his complex machine." It has been pointed out that the speed of the Mark II was "comparable to the first Intel microprocessor chip introduced thirty years later".

When the night staff arrived for work just before midnight on 4th June, 1944 they were informed that tomorrow was D-Day: "They told us that D-Day was today and they wanted every possible message decoded as fast as possible. But then it was postponed because the weather was so bad and that meant we girls knew it was going to take place, so we had to stay there until D-Day. We slept where we could and worked when we could and of course then they set off on June 6, and that was D-Day."

Winston Churchill and his commanders wanted to know if the deception plans for the D-Day landings had been successful. Developed by two agents, Tomás Harris and Juan Pujol: The key aims of the deception were: "(a) To induce the German Command to believe that the main assault and follow up will be in or east of the Pas de Calais area, thereby encouraging the enemy to maintain or increase the strength of his air and ground forces and his fortifications there at the expense of other areas, particularly of the Caen area in Normandy. (b) To keep the enemy in doubt as to the date and time of the actual assault. (c) During and after the main assault, to contain the largest possible German land and air forces in or east of the Pas de Calais for at least fourteen days."

Harris devised a plan of action for Pujol (code name GARBO). He was to inform the Germans that the opening phase of the invasion was under way as the airborne landings started, and four hours before the seaborne landings began. "This, the XX-Committee reasoned, would be too later for the Germans to do anything to do anything to frustrate the attack, but would confirm that GARBO remained alert, active, and well-placed to obtain critically important intelligence."

Christopher Andrew has explained how the strategy worked: "During the first six months of 1944, working with Tomás Harris, he (GARBO) sent more than 500 messages to the Abwehr station in Madrid, which as German intercepts revealed, passed them to Berlin, many marked 'Urgent'... The final act in the pre-D-Day deception was entrusted, appropriately, to its greatest practitioners, GARBO and Tomás Harris. After several weeks of pressure, Harris finally gained permission for GARBO to be allowed to radio a warning that Allied forces were heading towards the Normandy beaches just too late for the Germans to benefit from it."

Tommy Flowers had a meeting with General Dwight D. Eisenhower on 5th June. He was able to tell Eisenhower that Adolf Hitler was not sending any extra troops to Normandy and still believed that the Allied troops would land east of the Pas de Calais. Flowers was also able to report that Colossus Mark II had decoded message from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel that one of the drop sites for an US parachute division was the base for a German tank division. As a result of this information the drop site was changed.

Jean Thompson later explained her role in the operation in the book, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "Most of the time I was doing wheel setting, getting the starting positions of the wheels. There would be two Wrens on the machine and a duty officer, one of the cryptanalysts - the brains people, and the message came in on a teleprinted tape. If the pattern of the wheels was already known you put that up at the back of the machine on a pinboard. The pins were bronze, brass or copper with two feet and there were double holes the whole way down the board for cross or dot impulses to put up the wheel pattern. Then you put the tape on round the wheels with a join in it so it formed a complete circle. You put it behind the gate of the photo-electric cell which you shut on it and, according to the length of the tape, you used so many wheels and there was one moveable one so that could get it taut. At the front there were switches and plugs. After you'd set the thing you could do a letter count with the switches. You would make the runs for the different wheels to get the scores out which would print out on the electromatic typewriter. We were looking for a score above the random and one that was sufficiently good, you'd hope was the correct setting. When it got tricky, the duty officer would suggest different runs to do."

At the end of the war Winston Churchill issued orders that the ten Colossus computers were destroyed and broken into "pieces no bigger than a man's hand". Harry Fensom was one of those who was involved in breaking-up the computers. "I believe some panels went with Max Newman to Manchester University." Jerry Roberts later recalled: "The Colossus machines were all destroyed, except two which got away. There were ten machines - eight were dismantled and destroyed, and two were kept at Cheltenham at the new GCHQ." Tommy Flowers was ordered to destroy all documentation and burnt them in a furnace at Dollis Hill. He later said of that order: "That was a terrible mistake. I was instructed to destroy all the records, which I did. I took all the drawings and the plans and all the information about Colossus on paper and put it in the boiler fire. And saw it burn."

Tommy Flowers returned to Dollis Hill where he became head of the section developing electronic switching, forerunner of the subscriber trunk dialling (STD) system introduced in the post-war decades. He also assisted the National Physical Laboratory's project to build the ACE, an early stored-program computer. As Post Office chief engineer Flowers designed an electronic random-number generator, ERNIE, operational from 1957, to pick winners among holders of premium bonds.

Frederick Winterbotham approached the government and asked for permission to reveal the secrets of the work done at Bletchley Park. The intelligence services reluctantly agreed and Winterbotham's book, The Ultra Secret, was published in 1974. Those who had contributed so much to the war effort could now receive the recognition they deserved. Unfortunately, some of the key figures such as Alan Turing, Alastair Denniston and Alfred Dilwyn Knox were now dead.

In 1977 Flowers's role was recognized, after groundbreaking historical research by the computer scientist Brian Randell, and he was awarded an honorary degree by Newcastle University. He was the first recipient of the Post Office's Martlesham medal, in 1980. Tommy Flowers died at his home, 8 Holland Court, Page Street, Mill Hill, London, on 28th October 1998.

On this day in 1913 Lilian Lenton was arrested and charged with setting fire to a house in Cheltenham. Lilian Ida Lenton, the eldest daughter of a carpenter-joiner, was born in Leicester in January 1891. After leaving school she trained to be a dancer and took the name "Ida Inkley". A supporter of women's suffrage she heard Emmeline Pankhurst speak and later recalled that she "made up my mind that night that as soon as I was twenty-one and my own boss... I would volunteer".

Soon after joining the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) she took part on 4th March, 1912, window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. The severely disabled, May Billinghurst, agreed to hide some of the stones underneath the rug covering her knees. According to Votes for Women: "From in front, behind, from every side it came - a hammering, crashing, splintering sound unheard in the annals of shopping... At the windows excited crowds collected, shouting, gesticulating. At the centre of each crowd stood a woman, pale, calm and silent."

Lilian Lenton was one of the 200 suffragettes were arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration. She was found guilty and was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. After leaving prison she joined the campaign to destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. By December, 1912, the government claimed that over 5,000 letters had been damaged by the WSPU. The main figure in this campaign was May Billinghurst. Lenton recalled: "She (May Billinghurst) would set out in her chair with many little packages from which, when they were turned upside down, there flowed a dark brown sticky fluid, concealed under the rug which covered her legs. She went undeviatingly from one pillar box to another, sometimes alone, sometimes with another suffragette to do the actual job, dropping a package into each one."

In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst began organizing a secret arson campaign. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest." Occasionally they were caught and convicted, usually they escaped. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

Lilian Lenton was one of the woung women involved in this arson campaign. Along with Olive Wharry she embarked on a series of terrorist acts. She was arrested on 19th February 1913, soon after setting fire to the tea pavilion in Kew Gardens. In court it was reported: "The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry. In one of the bags which the women threw away were found a hammer, a saw, a bundle to tow, strongly redolent of paraffin and some paper smelling strongly of tar. The other bag was empty, but it had evidently contained inflammables."

While in custody, Lenton went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed. She was quickly released from prison when she became seriously ill after food entered her lungs. After she recovered she managed to evade recapture until arrested in June 1913 in Doncaster and charged with setting fire to to a railway station at Blaby, Leicestershire. She was held in custody at Armley Prison in Leeds. She immediately went on hunger-strike and was released after a few days under the Cat & Mouse Act. The following month she escaped to France in a private yacht.

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Lilian Lenton has stated that her aim was to burn two buildings a week, in order to create such a condition in the country that it would prove impossible to govern without the consent of the governed." Lenton was soon back in England setting fire to buildings but in October 1913 she was arrested at Paddington Station. Once again she went on hunger-strike and was forcibly fed, but once again she was released when she became seriously ill.

Lenton was released on licence on 15th October. She escaped from the nursing home and was arrested on 22nd December 1913 and charged with setting fire to a house in Cheltenham. After another hunger-and-thirst strike, she was released on 25th December to the care of Mrs Impey in King's Norton. Once again she escaped and evaded the police until early May 1914 when she was arrested in Birkenhead. She was only in prison for a few days before she was released under the Cat & Mouse Act.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

In 1914 Eveline Haverfield, a member of the WSPU, founded the Women's Emergency Corps, an organisation which helped organize women to become doctors, nurses and motorcycle messengers. Later she was appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps, Haverfield was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia. In August, 1916, Lilian Lenton went with Haverfield, Dr. Else Inglis, Elsie Bowerman, and Vera Holme to the Balkan Front.

Haverfield was appointed head of the transport column and in August 1916 she was dispatched to Russia. Her biographer, Elizabeth Crawford, has commented: "Haverfield sailed for Russia, in charge of the unit's transport column, which comprised seventy-five women noted for their smart uniforms and shorn locks. She herself is invariably described as being small, neat, and aristocratic, able to command devotion from her troops, although some of her peers, not so enamoured, were scathing of her ability."

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918. Several of the women involved in the suffrage campaign stood for Parliament. Only one, Constance Markiewicz, standing for Sinn Fein, was elected. Lenton later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30."

In 1924 Lilian Lenton was employed as a travelling organizer and speaker for the Women's Freedom League. During this period she often stayed with Alice Schofield in Middlesbrough. After 1925 she was financial secretary of the National Union of Women Teachers. Lilian Lenton died in 1972.

On this day in 1915 Roland Leighton was killed on the Western Front. Leighton, the son of Robert Leighton (1858-1934) and Marie Connor Leighton (1865-1941), was born in London on 27th March 1895. His father was literary editor at The Daily Mail, and was the author of popular adventure books for boys. His mother was also a writer and had published several novels.

Leighton was educated at Uppingham School where he met Edward Brittain and Victor Richardson. They were described by Roland's mother, as the "Three Musketeers". The three men joined the Officers' Training Corps (OTC). A fellow student, C.R.W. Nevinson, described the mood of the school as "appalling jingoism". The headmaster told them on Speech Day that: "If a man can't serve his country he's better dead."

As Alan Bishop has pointed out in his book, Letters From a Lost Generation (1998): "The OTC provided the institutional mechanism for public school militarism. But a more complex web of cultural ideas and assumptions, some taken from the classics, some from popular fiction, some even developed through competitive sports on the playing fields, was instilled by schoolmasters in their pupils, and contributed to the generation of 1914's overwhelming willingness to march off in search of glory." Leighton was an enthusiastic patriot and he was appointed as colour-sergeant of the OTC.

In June 1913, Edward Brittain introduced him to his sister, Vera Brittain. They soon developed a close relationship. Roland gave her a copy of Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm. He told her that the main character, Lyndall, reminded him of her. Vera replied in a letter dated 3rd May 1914: "I think I am a little like Lyndall, and would probably be more so in her circumstances, uncovered by the thin veneer of polite social intercourse." Vera wrote in her diary that "he (Roland) seems even in a short acquaintance to share both my faults and my talents and my ideas in a way that I have never found anyone else to yet."

In July 1914, Leighton was awarded the Classical Postmastership at Merton College. On the outbreak of the First World War, he decided not to take his place at Oxford University in order to join the British Army. Vera Brittain wrote to Roland about his decision to take part in the war: "I don't know whether your feelings about war are those of a militarist or not; I always call myself a non-militarist, yet the raging of these elemental forces fascinates me, horribly but powerfully, as it does you. You find beauty in it too; certainly war seems to bring out all that is noble in human nature, but against that you can say it brings out all the barbarous too. But whether it is noble or barbarous I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration."

He was initially rejected due to poor eyesight but two months later obtained a commission in the Royal Norfolk Regiment. Lieutenant Leighton transferred to the 7th Worcester Regiment in an attempt to get to the Western Front as soon as possible. He arrived in the trenches at Armentieres in April 1915. Before actually seeing any action he became aware of the reality of war. Soon after arriving at the front-line trenches he wrote to Vera Brittain: "I went up yesterday morning to my fire trench, through the sunlit wood, and found the body of the dead British soldier hidden in the undergrowth a few yards from the path. He must have been shot there during the wood fighting in the early part of the war and lain forgotten all the time. The ground was slightly marshy and the body had sunk down into it so that only the toes of his boots stuck up above the soil. His cap and equipment were just by the side, half-buried and rotting away. I am having a mound of earth thrown over him, to add one more to the other little graves in the wood." He soon became disillusioned with the war. He told Vera later that month: "There is nothing glorious in trench warfare. It is all a waiting and a waiting and taking of petty advantages - and those who can wait longest win. And it is all for nothing - for an empty name, for an ideal perhaps - after all."

In a letter to Edward Brittain a couple of days later he spoke of his desire to return home: "Our position here is very strong, and in consequence life tends to become somewhat monotonous in time. The snipers are a chronic nuisance, but we do not get shelled very often, which is a distinct advantage. We have been here 10 days and have had only 1 killed and 6 wounded (none seriously). Armstrong got a bullet through his left wrist and has been sent home - lucky devil! They have stopped all leave other than sick leave now, so that I may be stuck out here for an indefinite period. As far as I can see, the war may last another two years if it goes on at the same rate as at present."

The trenches at Armentieres were very quiet and it was not until May that Leighton lost the first of his men: "One of my men has just been killed - the first. I have been taking the things out of his pockets and tying them round in his handkerchief to be sent back somewhere to someone who will see more than a torn letter, and a pencil, and a knife and a piece of shell. He was shot through the left temple while firing over the parapet. I did not actually see it - thank Heaven. I only found him lying very still at the bottom of the trench with a tiny stream of red trickling down his cheek onto his coat. He has just been carried away. I cannot help thinking how ridiculous it was that so small a thing should make such a change... I was talking to him only a few minutes before... I do not quite know how I felt at the moment. It was not anger (even now I have no feeling of animosity against the man who shot him) only a great pity, and a sudden feeling of impotence."

While on leave during August 1915 Roland Leighton became engaged to Vera Brittain. On his return to France he was stationed in trenches near Hebuterne, north of Albert. On the 26th November 1915 he wrote a letter to Vera that highlighted his disillusionment with the war. "It all seems such a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty. And if one does not even get a letter occasionally from someone who despite his shortcomings perhaps understands and sympathises it must make it all the worse... until one may possibly wonder whether it would not have been better to have met him at all or at any rate until afterwards. I sometimes wish for your sake that it had happened that way."

On the night of 22nd December 1915 he was ordered to repair the barbed wire in front of his trenches. It was a moonlit night with the Germans only a hundred yards away and Roland Leighton was shot by a sniper. His last words were: "They got me in the stomach, and it's bad." He died of his wounds at the military hospital at Louvencourt on 23rd December 1915. He is buried in the military cemetery near Doullens.

His friend, Victor Richardson, later recalled: "In the first place the wire in front of the trenches has to be kept in good order under all circumstances. The fact that there was a bright moon early in the night would not prevent the enemy making an attack later on in the night, or at dawn; and there is always the chance that if the wire was down they might get through, especially as any weak spots would have been marked down in daylight. This view would almost certainly be held by the officer responsible for the defence of the sector."

In her book, Testament of Youth (1933) Vera Brittain recalled visiting Roland's family home in Hassocks. "I arrived at the cottage that morning to find his mother and sister standing in helpless distress in the midst of his returned kit, which was lying, just opened, all over the floor. The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and I wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics - the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rages made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant."

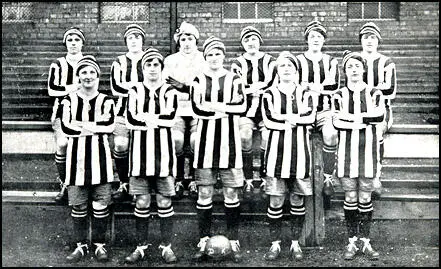

On this day in 1922 Dick Kerr Ladies arrived in Quebec on their football tour. Alfred Frankland decided to take the Dick Kerr Ladies on a tour of Canada and the United States. The team included Jennie Harris, Daisy Clayton, Alice Kell, Florrie Redford, Florrie Haslam, Alice Woods, Jessie Walmsley, Lily Parr, Molly Walker, Carmen Pomies, Lily Lee, Alice Mills, Annie Crozier, May Graham, Lily Stanley and R. J. Garrier. Their regular goalkeeper, Peggy Mason, was unable to go due to the recent death of her mother.

When the Dick Kerr Ladies arrived in Canada they discovered that the Dominion Football Association had banned them from playing against Canadian teams. They were accepted in the United States, and even though they were sometimes forced to play against men, they lost only 3 out of 9 games. They visited Boston, Baltimore, St. Louis, Washington, Detroit, Chicago and Philadelphia during their tour of America.

Florrie Redford was the leading scorer on the tour but Lily Parr was considered the star player and American newspapers reported that she was the "most brilliant female player in the world". One member of the team, Alice Mills, met her future husband at one of the games, and would later return to marry him and become an American citizen.

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. The role of women changed dramatically during the First World War. As men left jobs to fight overseas, they were replaced by women. Women filled many jobs brought into existence by wartime needs. The greatest increase of women workers was in engineering. Over 700,000 women worked in the highly dangerous munitions industry.

The women working in factories began to play football during lunch-breaks. Teams were formed and on Christmas Day in 1916, a game took place between Ulverston Munitions Girls and another group of local women. The munitionettes won 11-5. Soon afterwards, a game between munitions factories in Swansea and Newport. The Hackney Marshes National Projectile Factory formed a football team and played against other factories in London.

David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, encouraged these games as it helped reinforce the image of women doing the jobs normally done by men now needed to fight on the Western Front. This was especially important after the introduction of conscription in 1916. These matches also helped to raise money for wartime charities.

Alfred Frankland worked in the offices of the Dick Kerr factory in Preston. During the First World War the company produced locomotives, cable drums, pontoon bridges, cartridge boxes and munitions. By 1917 it was producing 30,000 shells per week. Frankland used to watch the young women workers from his office window, kicking the ball around in their dinner-breaks. Alice Norris, one of the young women who worked at the factory later recalled these games: "We used to play at shooting at the cloakroom windows. they were little square windows and if the boys beat us at putting a window through we had to buy them a packet of Woodbines, but if we beat them they had to buy us a bar of Five Boys chocolate."

Grace Sibbert eventually emerged as the leader of the women who enjoyed playing football during the dinner-breaks. Born on 13th October, 1891, Grace's husband took part in the Battle of the Somme and in 1916 had been captured by the German Army and was at the time in a POW camp. Alfred Frankland suggested to Grace Sibbert that the women should form a team and play charity matches. Sibbert liked the idea and Frankland agreed to became the manager of the team.

Frankland arranged for the women to play a game on Christmas Day 1917, in aid of the local hospital for wounded soldiers at Moor Park. Frankland persuaded Preston North End to allow the women to play the game at their ground at Deepdale. It was the first football game to be played on the ground since the Football League programme was cancelled after the outbreak of the First World War. Over 10,000 people turned up to watch the game. After paying out the considerable costs of putting on the game, Frankland was able to donate £200 to the hospital (£41,000 in today's money).

Dick Kerr's beat the Arundel Courthard Foundry, 4-0. They went onto play and defeat other factories based in Barrow-in-Furness and Bolton. The stars of the team included the captain, Alice Kell, the centre-forward, Florrie Redford, and the hard-tackling defender, Lily Jones.

On 21st December, 1918, the team played against Lancaster Ladies at Deepdale and lost the game 1-0. Alfred Frankland was impressed with the performances of three of the women playing for Lancaster: Jennie Harris, Jessie Walmsley and Anne Hastie. Four days later, the three women had been persuaded to join the Preston side and played against Bolton Ladies on Christmas Day, 1918. Soon afterwards, another Lancaster player, Molly Walker, joined the side. Frankland also recruited players from Bolton (Florrie Haslam) and Liverpool (Daisy Clayton).

At the end of the First World War most women lost their jobs in the munitions factories. However, some retained their interest in football. For example, the Sutton Glass Works women's football team reformed as St Helens Ladies' AFC. Some teams retained the support of their employers. This included the Dick, Kerr factory in Preston.

At first men found it difficult to accept that women should play football. As David J. Williamson argued in Belles of the Ball (1991): "Nor surprisingly, it was extremely difficult for many men to accept the idea of ladies playing what had always been regarded as a male preserve, their sport. Those who had been away at the front during the Great War would have had no real idea as to how the country was changing in their absence; how the role of their womenfolk within society was beginning to change quite dramatically, responding to the opportunity they had been given."

In early 1919 Dick Kerr Ladies beat St. Helens Ladies 6-1. Alfred Frankland was very impressed with the performances of Alice Woods and her fourteen year-old team-mate, Lily Parr. After the game Frankland asked the two women to join his team. Records show that Frankland paid these women 10 shillings a game. In today's money that amounted to about £100. He also paid their travelling expenses.

Women's football games were extremely popular. For example, a game against Newcastle United Ladies played at St. James's Park, in September, 1919, attracted a crowd of 35,000 people and raised £1,200 (£250,000) for local war charities.

Games were usually preceded by a laying of wreaths on the graves of local football players killed during the First World War. For example, when they played in Blackburn, they placed a wreath in remberance of Edwin Latheron, the English international inside forward who had been killed at Passchendaele.

Lily Parr was one of the main stars of the team and in her first season scored 43 goals for the club. Gail J. Newsham wrote about Parr in her book, In a League of their Own (1994): "Standing almost six feet tall, with jet black hair, her power and skill was admired and feared, wherever she played. She was an extremely unselfish player who could pin-point a pass with amazing accuracy and was also a marvellous ball player. And she was probably responsible in one way or another, for most of the goals that were scored by the team".

In 1920 a local newspaper wrote about this talented 14 year old: "There is probably no greater football prodigy in the whole country. Not only has she speed and excellent ball control, but her admirable physique enables her to brush off challenges from defenders who tackle her. She amazes the crowd where ever she goes by the way she swings the ball clean across the goalmouth to the opposite wing."

One of her team-mates, Joan Whalley, remarked on Parr's sense of humour: "When the older players were getting ready for a match, there were elastic stockings going on knee's and strapping up of ankles, there were bandages here there and everywhere. Then Parr walked in, and she stood looking around at them all and said, "well, I don't know about Dick Kerr Ladies football team, it looks like a bloody trip to Lourdes to me!"

The women came under a great deal of pressure from their families not to play football. Molly Walker was treated as an outcast by her boyfriend's family because they did not approve of her wearing shorts and showing her legs.

Dick Keer Ladies trained at Ashton Park, a sports ground owned by the company. Several members of the Preston North End team helped with the coaching. This included Bob Holmes, Johnny Morley, Billy Greer and Jack Warner.

The managing director of the Dick, Kerr Company was John Kerr. He was also the Conservative Party MP for Preston. In 1919 the company was purchased by English Electric.

In 1920 Alfred Frankland arranged for the Federation des Societies Feminine Sportives de France to send a team to tour England. Madame Milliat, who had founded the federation, was a great advocate of women playing football: "In my opinion, football is not wrong for women. Most of these girls are beautiful Grecian dancers. I do not think it is unwomanly to play football as they do not play like men, they play fast, but not vigorous football."

Frankland believed that his team was good enough to represent England against a French national team. Four matches were arranged to be played at Preston, Stockport, Manchester and London. The matches were played on behalf of the National Association of Discharged and Disabled Soldiers and Sailors.

A crowd of 25,000 people turned up to the home ground of Preston North End to see the first unofficial international between England and France. England won the game 2-0 with Florrie Redford and Jennie Harris scoring the goals.

The two teams travelled to Stockport by charabanc. This time England won 5-2. The third game was played at Hyde Road, Manchester. Over 12,000 spectators saw France obtain a 1-1 draw. Madame Milliat reported that the first three games had raised £2,766 for the ex-servicemens fund.

The final game took place at Stamford Bridge, the home of Chelsea Football Club. A crowd of 10,000 saw the French Ladies win 2-1. However, the English Ladies had the excuse of playing most of the game with only ten players as Jennie Harris suffered a bad injury soon after the game started. This game caused a stir in the media when the two captains, Alice Kell and Madeline Bracquemond, kissed each other at the end of the match.

On 28th October, 1920. Alfred Frankland took his team to tour France. On Sunday 31st October, 22,000 people watched the two sides draw 1-1 in Paris. However, the game ended five minutes early when a large section of the crowd invaded the pitch after disputing the decision by the French referee to award a corner-kick to the English side. After the game Alice Kell said the French ladies were much better playing on their home ground.

The next game was played in Roubaix. England won 2-0 in front of 16,000 spectators, a record attendance for the ground. Florrie Redford scored both the goals. England won the next game at Havre, 6-0. As with all the games, the visitors placed a wreath in memory of allied soldiers who had been killed during the First World War.

The final game was in Rouen. The English team won 2-0 in front of a crowd of 14,000. When the team arrived back in Preston on 9th November, 1920, they had travelled over 2,000 miles. As captain of the team, Alice Kell made a speech where she said: "If the matches with the French Ladies serve no other purpose, I feel that they will have done more to cement the good feeling between the two nations than anything which has occurred during the last 50 years."

Soon after arriving back in Preston, Alfred Frankland was informed that the local charity for Unemployed Ex Servicemen was in great need for money to buy food for former soldiers for Christmas. Frankland decided to arrange a game at between Dick Kerr Ladies and a team made up of the rest of England. Deepdale, the home of Preston North End was the venue. To maximize the crowd, it was decided to make it a night game. Permission was granted by the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, for two anti-aircraft searchlights, generation equipment and forty carbide flares, to be used to floodlight the game.

Over 12,000 people came to watch the match that took place on 16th December, 1920. It was also filmed by Pathe News. Bob Holmes, a member of the Preston team that won the first Football League title in 1888-89, had the responsibility of providing whitewashed balls at regular intervals. Although one of the searchlights went out briefly on two occasions, the players coped well with the conditions. Dick Kerr Ladies showed they were the best woman's team in England by winning 4-0. Jennie Harris scored twice in the first half and Florrie Redford and Minnie Lyons added further goals before the end of the game. A local newspaper described the ball control of Harris as "almost weird". He added "she controlled the ball like a veteran league forward, swerved, beat her opponents with the greatest of ease, and passed with judgment and discretion". As a result of this game, the Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund received over £600 to help the people of Preston. This was equivalent to £125,000 in today's money.

On 26th December, 1920, Dick Kerr Ladies played the second best women's team in England, St Helens Ladies, at Goodison Park, the home ground of Everton. The plan was to raise money for the Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund in Liverpool. Over 53,000 people watched the game with an estimated 14,000 disappointed fans locked outside. It was the largest crowd that had ever watched a woman's game in England.

Florrie Redford, Dick Kerr Ladies' star striker, missed her train to Liverpool and was unavailable for selection. In the first half, Jennie Harris gave Dick Keer Ladies a 1-0 lead. However, the team was missing Redford and so the captain and right back, Alice Kell, decided to play centre forward. It was a shrewd move and Kell scored a second-half hat trick which enabled her side to beat St Helens Ladies 4-0.

The game at Goodison Park raised £3,115 (£623,000 in today's money). Two weeks later the Dick Kerr Ladies played a game at Old Trafford, the home of Manchester United, in order to raise money for ex-servicemen in Manchester. Over 35,000 people watched the game and £1,962 (£392,000) was raised for charity.

The French team arrived for another tour of England in May, 1921. Their star player was Carmen Pomies. She was an outstanding athlete and was a champion javelin thrower in France. Pomies could play in goal or in the outfield. She was so good that Alfred Frankland persuaded her to live in Preston and play for Dick Kerr Ladies. Her first game was against Coventry Ladies on 6th August, 1921.

In 1921 the Dick Kerr Ladies team was in such demand that Alfred Frankland had to refuse 120 invitations from all over Britain. The still played 67 games that year in front of 900,000 people. It has to be remembered that all the players had full-time jobs and the games had to be played on Saturday or weekday evenings. As Alice Norris pointed out: "It was sometimes hard work when we played a match during the week because we would have to work in the morning, travel to play the match, then travel home again and be up early for work the next day."

On 14th February, 1921, 25,000 people watched Dick Kerr Ladies beat the Best of Britain, 9-1. Lily Parr (5), Florrie Redford (2) and Jennie Harris (2) got the goals. Representing their country, the Preston team beat the French national side 5-1 in front of 15,000 people at Longton. Parr scored all five goals.

The Dick Kerr Ladies did not only raise money for Unemployed Ex Servicemens Distress Fund. They also helped local workers who were in financial difficulty. The mining industry in particular suffered a major recession after the war. In 1920 the mine-owners notified their workers that miners' wages were to be reduced. Robert Smillie, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) called a strike in an effort to persuade the owners to change their minds. Under the terms of the Triple Industrial Alliance, the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) declared that they take industrial action in support of the miners. However, at the last moment, the leaders of the NUR and TGWU changed their minds, and although the miners went ahead with their strike they eventually had to give in and accept lower wages.

In March, 1921, the mine-owners announced a further 50% reduction in miner's wages. When the miners refused to accept this pay-cut, they were locked out from their jobs. On April 1 and, immediately on the heels of this provocation, the government put into force its Emergency Powers Act, drafting soldiers into the coalfield.

The government and the mine-owners attempted to starve the miners into submission. Several members of the Dick Kerr team came from mining areas like St. Helens and held strong opinions on this issue and games were played to raise money for the families of those men locked out of employment. As Barbara Jacobs pointed out in The Dick, Kerr's Ladies: "Women's football had come to be associated with charity, and had its own credibility. Now it was used as a tool to help the Labour Movement and the trade unions. It had, it could be said, become a politically dangerous sport, to those who felt the trade unions to be their enemies.... Women went out to support their menfolk, a Lancashire tradition, was causing ripples in a society which wanted women to revert to their prewar roles as set down by their masters, of keeping their place, that place being in the home and kitchen. Lancashire lasses were upsetting the social order. It wasn't acceptable."

The 1921 Miners Lock-Out caused considerable suffering in mining areas in Wales and Scotland. This was reflected by games played in Cardiff (18,000), Swansea (25,000) and Kilmarnock (15,000). Dick Kerr Ladies represented England beat Wales on two successive Saturdays. They also beat Scotland on 16th April, 1921.

The Football Association was appalled by what they considered to be women's involvement in national politics. It now began a propaganda campaign against women's football. A new rule was introduced that stated no football club in the FA should allow their ground to be used for women's football unless it was prepared to handle all the cash transactions and do the full accounting. This was an attempt to smear Alfred Frankland with financial irregularities.

Once again the issue was raised about the health risks of women's football. Dr Elizabeth Sloan Chesser said: "There are physical reasons why the game is harmful to women. It is a rough game at any time, but it is much more harmful to women than men. They may receive injuries from which they may never recover." Dr Mary Scharlieb, a Harley Street Physician added: "I consider it a most unsuitable game, too much for a woman's physical frame."

Barbara Jacobs argued in The Dick, Kerr's Ladies that "the FA brought out its tame doctors to verify that, in fact, football did terrible things to women's bodies. Mr Eustice Miles had a scientific reason for believing this, or so he said - "The kicking is too jerky a movement for women and the strain is likely to be severe." So are we to assume that women's bodies are unsuited to jerky movements? That's put paid to sex, hasn't it?"

Alfred Frankland invited Dr Mary Lowry to watch a game being played by Dick Kerr Ladies. Afterwards she commented: "From what I saw, football is no more likely to cause injuries to women than a heavy day's washing."

The captain of Huddersfield Atalanta argued: "If football were dangerous some ill-effect would have been seen by now. I know that all our girls are healthier and, speaking personally, I feel worlds better than I did a year ago. Housework isn't half the trouble it used to be, because there is always Saturday's game and the week night training to freshen me up."

The captain of Plymouth Ladies gave an interview where she argued: "The controlling body of the F.A. are a hundred years behind the times and their action is purely sex prejudice. Not one of our girls has felt any ill effects from participating in the game."

On 5th December 1921, the Football Association issued the following statement: "Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, the Council feel impelled to express their strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged. Complaints have been made as to the conditions under which some of these matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of the receipts to other than Charitable objects. The Council are further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to Charitable objects. For these reasons the Council requests the clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.

This measure removed the ability of women to raise significant sums of money for charity as they were now barred from playing at all the major venues. The Football Association also announced that members were not allowed to referee or act as linesman at any women's football match.

The Dick Keer Ladies team were shocked by this decision. Alice Kell, the captain, spoke for the other women when she said: "We play for the love of the game and we are determined to carry on. It is impossible for the working girls to afford to leave work to play matches all over the country and be the losers. I see no reason why we should not be recompensated for loss of time at work. No one ever receives more than 10 shillings per day."

On this day in 1936 Emma Sproson died.

Emma Lloyd, one of the seven children of John Lloyd and Ann Johnson Lloyd, was born on 13 April 1867 at Pikehelve Street, West Bromwich. Her father was a canal boat builder who drank heavily and this resulted in a childhood of extreme poverty. The family moved to Bilston in 1875.

According to her biographer, Jane Martin: "Emma had little formal schooling and joined the casual labour market at the age of eight: picking coal from the pit mounds and running errands. A year later she left home to enter the household of a local milkwoman where she helped with the cooking, cleaning, and evening delivery, though she did attend school four days a week. In 1880 she obtained a full-time position that combined shop work with domestic service. Later she was dismissed without a reference when she reported that her mistress's brother had made sexual advances towards her. Now unemployed, Emma moved to Lancashire to find work. About that time she began teaching in a Sunday school and was introduced to the church debating society."

On 1st August 1896, Emma married Frank Sproson, postman and secretary of the Wolverhampton branch of the Independent Labour Party. Emma Sproson now became active in socialist politics in the area. She later recalled how she became involved in the women's suffrage movement. She attended a meeting being held by George Curzon, the Conservative Party MP for Southport. He refused to answer her question because "she was a woman and did not have the vote".

On 26th October 1906, Frank Sproson invited Emmeline Pankhurst, the founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) to address a meeting of the Wolverhampton ILP. Pankhurst stayed at the Sprosons' home and after the meeting Emma joined the WSPU. Over the next few months Sproson joined forces with Jennie Baines, Mabel Capper, Minnie Baldock and Ada Nield Chew, to speak at meetings in order to recruit working-class women to the cause.