Harry Fensom

Harry Fensom was born in the East End of London in 1921. He won a scholarship to the Royal Liberty Grammar School in Gidea Park, Romford. He left school at sixteen and went to work for the Post Office and took his City & Guilds examinations at night school. (1)

Fensom became an electronic engineer at telephone exchanges in London. On the outbreak of the Second World War he was sent to the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill, where he worked under Tommy Flowers. The station was dedicated mainly to research in telecommunications and was responsible for the development of the Trans-Atlantic telephone cable. As Alan Hodges has pointed out: "His (Flowers) major research interest over the years had been long distance signalling, and in particular the problem of transmitting control signals, so enabling human operators to be replaced by automatic switching equipment." (2)

Harry Fensom at Bletchley Park

In February 1941, Gordon Radley, the director of the Post Office Research Station was contacted by officials of Bletchley Park, the government's codebreaking establishment. Alan Turing wanted help in building a decoder for a machine he had designed to decipher messages sent by the German military during the Second World War. Turing was put in contact with Tommy Flowers. Although the decoder project was abandoned, Turing was impressed with Flowers's work, and in February 1943 introduced him to Max Newman, who had been given the problem of dealing with the Lorenz SZ machine that was used to encrypt communications between Adolf Hitler and his generals.

The Lorenz SZ operated in a similar way to the Enigma Machine, but was far more complicated, and it provided the Bletchley codebreakers with an even greater challenge. It used a 32-letter Baudot alphabet. "While Enigma machines were capable of 159 trillion settings, the number of the combinations possible with the Lorenz SZ was estimated at 5,429,503,678,976 times greater." (3)

Newman came up with a way to mechanise the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher and therefore to speed up the search for wheel settings. (4) Flowers later explained the objective of Newman's machine: "The purpose was to find out what the positions of the code wheels were at the beginning of the message and it did that by trying all the possible combinations and there were billions of them. It tried all the combinations, which processing at 5,000 characters a second could be done in about half an hour. So then having found the starting positions of the cipher wheels you could decode the message." (5)

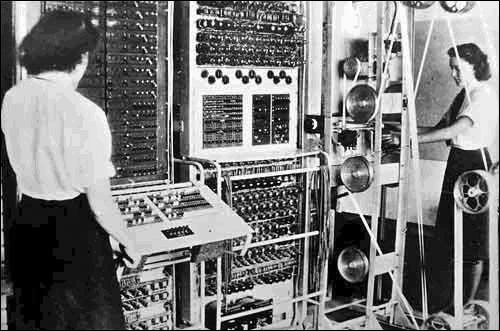

Colossus Mark I

The initial machine designed by Max Newman kept on breaking down. Tommy Flowers later recalled: "I was brought in to to make it work, but I very soon came to the conclusion that it would never work. It was dependent on paper tape being driven at very high speed by means of spiked wheels and the paper wouldn't stand up to it." Flowers suggested that Newman used valves instead of the old-fashioned electromechanical relay switches that had been used in Turing's machines. He claimed valves would do the same job much faster without the need for the synchronisation of the two tapes.

Gordon Welchman, a colleague at Bletchley Park, pointed out: "Flowers seems to have realized at once that synchronization 44 punched-tape operations need not depend on the mechanical process of using sprocket holes. He used photoelectric sensing, and at that early date he had enough confidence in the reliability of switching networks based on electronic valves (tubes, in America), rather than electromagnetic relays, to risk using such techniques on a grand scale. From his prewar experience, Flowers knew that most valve failures occurred when, or shortly after, power was switched on, and he designed his equipment with this in mind. He proposed a machine using 1,500 valves." (6)

Tommy Flowers claimed that Newman and his team of codebreakers were highly sceptical of his suggestion: "They wouldn't believe it. They were quite convinced that valves were very unreliable. This was based on their experience of radio equipment which was carted around, dumped around, switched on and off, and generally mishandled. But I'd introduced valves into telephone equipment in large numbers before the war and I knew that if you never moved them and never switched them off they would go on forever. They asked me how long it would take to produce the first machine. I said at least a year and they said that was terrible. They thought in a year the war could be over and Hitler could have won it so they didn't take up my idea." (7)

The project was now shelved. However, Tommy Flowers was so convinced that he could get Newman machine to work effectively he continued building the machine. At the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill, Flowers took Newman's blueprint and spent ten months turning it into the Colossus Computer, which he delivered to Bletchley Park on 8th December 1943, but was not fully operational until 5th February 1944. It consisted of 1,500 electronic valves, which were considerably faster than the relay switches used in Turing's machine. However, as Simon Singh, the author of The Code Book: The Secret History of Codes & Code-Breaking (2000) has pointed out than "more important than Colossus's speed was the fact that it was programmable. It was this fact that made Colossus the precursor to the modern digital computer." (8)

Newman's staff that operated the Colossus consisted of about twenty cryptanalysts, about six engineers, and 273 Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Jack Good was one of the cryptanalysts working under Newman: "The machine was programmed largely by plugboards. It read the tape at 5,000 characters per second... The first Colossus had 1,500 valves, which was probably far more than for any electronic machine previously used for any purpose. This was one reason why many people did not expect Colossus to work. But it began producing results also immediately. Most of the failures of valves were caused by switching the machine on and off." (9)

Harry Fensom later reported: "The Colossi were of course very large, hence their name, and gave off a lot of heat, ducts above them taking some of this away. However, we appreciated this on the cold winter nights, especially about two or three in the morning. When I came in out of the rain, I used to hang my raincoat on the chair in front of the hundreds of valves forming the rotor wheels and it soon dried off. Of course it was essential that the machines were never switched off, both to avoid damaging the valves and to ensure no loss of code-breaking time. So there was an emergency mains supply in the adjoining bay which took over automatically on mains failure." (10)

Colossus Mark II

In February, 1944, the Lorenz SZ40 machine was further modified in an attempt to prevent the British from decyphering it. With the invasion of Europe known to be imminent, it was a crucial period for the codebreakers, as it was vitally important for Berlin to break the code being used between Adolf Hitler in Berlin and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Army in western Europe. (11)

Tommy Flowers and Max Newman now began working on a more advanced computer, Colossus Mark II. Flowers later recalled: "We were told if we couldn't make the machine work by June 1st it would be too late to be of use. So we assumed that that was going to be D-Day, which was supposed to be a secret." The first of these machines went into service at Bletchley Park on 1st June 1944. It had 2,400 valves and could process the tapes five times as fast. "The effective speed of sensing and processing the five-bit characters on punched paper tape was now twenty-five thousand characters per second... Flowers had introduced one of the fundamental principles of the postwar digital computer - use of a clock pulse to synchronize all the operations of his complex machine." (12) It has been pointed out that the speed of the Mark II was "comparable to the first Intel microprocessor chip introduced thirty years later". (13)

When the night staff arrived for work just before midnight on 4th June, 1944 they were informed that tomorrow was D-Day: "They told us that D-Day was today and they wanted every possible message decoded as fast as possible. But then it was postponed because the weather was so bad and that meant we girls knew it was going to take place, so we had to stay there until D-Day. We slept where we could and worked when we could and of course then they set off on June 6, and that was D-Day." (14)

Tommy Flowers had a meeting with General Dwight D. Eisenhower on 5th June. He was able to tell Eisenhower that Adolf Hitler was not sending any extra troops to Normandy and still believed that the Allied troops would land east of the Pas de Calais. Flowers was also able to report that Colossus Mark II had decoded message from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel that one of the drop sites for an US parachute division was the base for a German tank division. As a result of this information the drop site was changed.

Jean Thompson later explained her role in the operation in the book, Station X: The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park (1998): "Most of the time I was doing wheel setting, getting the starting positions of the wheels. There would be two Wrens on the machine and a duty officer, one of the cryptanalysts - the brains people, and the message came in on a teleprinted tape. If the pattern of the wheels was already known you put that up at the back of the machine on a pinboard. The pins were bronze, brass or copper with two feet and there were double holes the whole way down the board for cross or dot impulses to put up the wheel pattern. Then you put the tape on round the wheels with a join in it so it formed a complete circle. You put it behind the gate of the photo-electric cell which you shut on it and, according to the length of the tape, you used so many wheels and there was one moveable one so that could get it taut. At the front there were switches and plugs. After you'd set the thing you could do a letter count with the switches. You would make the runs for the different wheels to get the scores out which would print out on the electromatic typewriter. We were looking for a score above the random and one that was sufficiently good, you'd hope was the correct setting. When it got tricky, the duty officer would suggest different runs to do." (15)

Harry Fensom - Post 1945

At the end of the war Winston Churchill issued orders that the ten Colossus computers were destroyed and broken into "pieces no bigger than a man's hand". Jerry Roberts later recalled: "The Colossus machines were all destroyed, except two which got away. There were ten machines - eight were dismantled and destroyed, and two were kept at Cheltenham at the new GCHQ." Tommy Flowers was ordered to destroy all documentation and burnt them in a furnace at Dollis Hill. He later said of that order: "That was a terrible mistake. I was instructed to destroy all the records, which I did. I took all the drawings and the plans and all the information about Colossus on paper and put it in the boiler fire. And saw it burn." (16)

Harry Fensom was one of those who was involved in breaking-up the computers. He told Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010): "I know some of the Colossi were broken up: we smashed thousands of valves and I believe some panels went with Max Newman to Manchester University. But the know-how remained with a few and the flexibility and modular innovations of Colossus led to the initiation of the British computer industry, such as the work at Manchester and NPL. And also of course to the beginning of electronic telephone exchanges. I therefore give my tribute to Dr Tom Flowers, without whom it would never have happened." (17)

After the war Harry Fensom continued to work for Post Office Research Station. He continued to work with Tommy Flowers and helped design an electronic random-number generator, ERNIE, operational from 1957, to pick winners among holders of premium bonds. (18) His son, Jim Fensom, later recalled: "His best known project was Ernie – the Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment, which draws the winning premium bond numbers every month – but he also helped to develop many aspects of electronic communication and computer technology that we take for granted today." (19)

Frederick Winterbotham approached the government and asked for permission to reveal the secrets of the work done at Bletchley Park. The intelligence services reluctantly agreed and Winterbotham's book, The Ultra Secret, was published in 1974. Those who had contributed so much to the war effort could now receive the recognition they deserved. (20) Unfortunately, some of the key figures such as Alan Turing, Alastair Denniston and Alfred Dilwyn Knox were now dead.

Over the next thirty years he gave several interviews on the work that he did at BP and contributed to the books, Colossus: Bletchley Park's Greatest Secret (2007), The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) and Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Code-breaking Computers (2010).

Harry Fensom died in November 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Harry Fensom, quoted by Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 264

The Colossi were of course very large, hence their name, and gave off a lot of heat, ducts above them taking some of this away. However, we appreciated this on the cold winter nights, especially about two or three in the morning. When I came in out of the rain, I used to hang my raincoat on the chair in front of the hundreds of valves forming the rotor wheels and it soon dried off. Of course it was essential that the machines were never switched off, both to avoid damaging the valves and to ensure no loss of code-breaking time. So there was an emergency mains supply in the adjoining bay which took over automatically on mains failure." (10)

(2) Harry Fensom, quoted by Sinclair McKay, the author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 270

I know some of the Colossi were broken up: we smashed thousands of valves and I believe some panels went with Max Newman to Manchester University. But the know-how remained with a few and the flexibility and modular innovations of Colossus led to the initiation of the British computer industry, such as the work at Manchester and NPL. And also of course to the beginning of electronic telephone exchanges. I therefore give my tribute to Dr Tom Flowers, without whom it would never have happened.

(3) Jim Fensom, The Guardian (8th November 2010)

My father, Harry Fensom, who has died aged 89, made important contributions to the development of electronic computers. He was one of Tommy Flowers's "band of brothers", who built Colossus and managed its installation and operation at Bletchley Park, the wartime code-breaking establishment in Buckinghamshire.

Colossus was the world's first large-scale, electronic programmable computer and was used to break the German Lorenz code. It is widely accepted that this shortened the second world war by many months. To his family, Harry was a hero, but because of the secrecy surrounding activities at Bletchley Park, for many decades few others knew about his wartime work.

He was born in the East End of London and won a scholarship to the Royal Liberty grammar school in Gidea Park, Romford. At 16, Harry resisted the opportunity to go to university and went to work for the Post Office by day and at night worked for his City & Guilds certificates. During the early war years, he was an electronic engineer at telephone exchanges in London and in due course he received his call-up papers for the army. He never made it into uniform, as he was unexpectedly sent to the Post Office Research Station at Dollis Hill, where he began working with Flowers. They worked on several projects related to codebreaking which culminated in a move to Bletchley Park – even my mother, Marget, did not know Harry's whereabouts. At the end of the war all traces of what they did were destroyed. "Winston Churchill wanted it expunged from people's minds," said Harry in an interview. "He didn't want any of it to be released."

After the war Harry continued to work for BT. His best known project was Ernie – the Electronic Random Number Indicator Equipment, which draws the winning premium bond numbers every month – but he also helped to develop many aspects of electronic communication and computer technology that we take for granted today. The end of 30 years of secrecy surrounding the codebreaking at Bletchley Park in 1974 coincided with his retirement. At last he could break his long silence. He assisted in the Colossus rebuild project at Bletchley Park and over the past 30 years read every book on the subject, and contributed to several.

Harry died a few months after Marget, to whom he had been married for 66 years. He is survived by me, my two sisters, Mary and Sally, and four grandchildren.