Jack Good

Isidore Jacob Gudak (Jack Good), the son of Polish-Jewish parents, was born in London on 9th December 1916. His father was a watchmaker. He was educated at the Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School where he developed a talent for mathematics and won a place at Jesus College, Cambridge. (1)

In 1938 Good graduated with first-class honours in mathematics and stayed on to work for his PhD. Good was also a very good chess player and was friends with Stuart Milner-Barry and Hugh Alexander, twice British national chess champion. (2) Alexander worked at the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) and in 1941 on his suggestion, Good was interviewed by Gordon Welchman. He later recalled: "When I arrived at Bletchley I was met at the station by Hugh Alexander, the British chess champion. On the walk to the office Hugh revealed to me a number of secrets about the Enigma. Of course, we were not really supposed to talk about such things outside the precincts of the office. I shall never forget that sensational conversation." (3)

Jack Good & Bletchley Park

Good worked under Alan Turing in Hut 8 on breaking the code of the Enigma Machine. (4) He later commented: "In the first week of June each year he (Alan Turing) would get a bad attack of hay fever, and he would cycle to the office wearing a service gas mask to keep the pollen off. His bicycle had a fault; the chain would come off at regular intervals. Instead of having it mended he would count the number of times the pedals went round and would get off the bicycle in time to adjust the chain by hand. Another of his eccentricities was that he chained his mug to the radiator pipes to prevent its being stolen. It was only after the war that we learned he was a homosexual. It was lucky we didn't know about it early on, because if they had known, he might not have obtained clearance and we might have lost the war." (5)

Turing fell out with Good when he caught him sleeping on the floor while on duty during a night shift. "At first, Turing thought Good was ill, but he was cross when Good explained that he was just taking a short nap because he was tired. For a few days afterwards, Turing would not deign to speak to Good, and he left the room if Good walked in. The relationship between the two men was only put onto a more harmonious footing after Turing realized that Good was a brilliant statistician; a few days after Turing had found Good sleeping on duty, Good suggested that by simplifying the statistics used during the Banburismus procedure the amount of time taken by the procedure could be drastically reduced without lessening its efficacy. Good's suggestion was quickly adopted and his reputation, in Turing's eyes, was salvaged." (6)

Alan Turing's Machine

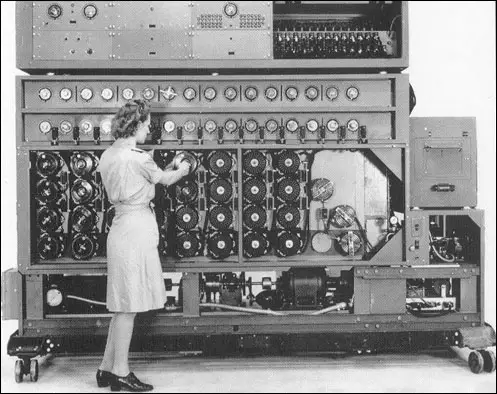

Jack Good helped Turing produce an engine that would increase the speed of the checking process. Turing finalized the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bombe") was in a copper-coloured cabinet. (7) "The result was a huge machine six-and-a-half feet tall, seven feet long and two feet wide. It weighed over a ton, with thirty-six 'scramblers' each emulating an Enigma machine and 108 drums selecting the possible key settings." (8) Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (9)

To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (10) The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. It was some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. (11) "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (12) They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (13)

Jack Good worked closely with Max Newman and Tommy Flowers in producing the pioneering Colossus computer. (14) Good later recalled: "The machine was programmed largely by plugboards. It read the tape at 5,000 characters per second and, at least in Mark II, the circuits were in quintuplicate so that in a sense the reading speed was 25,000 bits per second. This compares well with the speed of the electronic computers of the early 1950s. The first Colossus had 1,500 valves, which was probably far more than for any electronic machine previously used for any purpose. This was one reason why many people did not expect Colossus to work. But it was installed in December 1943 and began producing results almost immediately. Most of the failures of valves were caused by switching the machine on and off." (15)

Jack Good - Academic Career

In 1947 Newman invited Good to join him and Alan Turing at Manchester University. There for three years he lectured in mathematics and carried out research into computers - including the Manchester Mark 1. In 1948, he was recruited by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the successor to Government Code and Cypher School, where he stayed for the next eleven years. (16)

Jack Good moved to the United States in 1959. He was the author of papers such as Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine and Logic of Man and Machine. As a result of this work Stanley Kubrick employed him as an advisor on his film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). He was employed as professor of statistics at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Jack Good died on 5th April 2009.

Primary Sources

(1) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

In the first week of June each year he (Alan Turing) would get a bad attack of hay fever, and he would cycle to the office wearing a service gas mask to keep the pollen off. His bicycle had a fault; the chain would come off at regular intervals. Instead of having it mended he would count the number of times the pedals went round and would get off the bicycle in time to adjust the chain by hand.

Another of his eccentricities was that he chained his mug to the radiator pipes to prevent its being stolen. It was only after the war that we learned he was a homosexual. It was lucky we didn't know about it early on, because if they had known, he might not have obtained clearance and we might have lost the war...

Turing became a first class marathon runner. Unfortunately he developed some leg complaint that prevented his getting into the Olympic Games.

(2) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

Turing had gone to King's College, Cambridge, as a mathematical scholar at the age of 19, and was elected to a Fellowship at 23. M.H.A. Newman had been a university lecturer at Cambridge, anci it is believed Turing's work was sparked off by one of Newman's lectures. This was a lecture in which Newman discussed Hilbert's (David Hilbert, the German geometrician) view that any mathematical problem can be solved by a fixed and definite process. Turing seized on Newman's phraseology, "a purely mechanical process," and interpreted it as something that could be done by an automatic machine. He introduced a simple abstract machine in order to prove that Hilbert was wrong, and in fact showed that there is a "universal automaton" that can perform any calculation that any automaton can, if first provided with the appropriate instructions to input.

Turing was thus the first to arrive at an understanding of the universal nature of a (conceptual) digital computer that matches and indeed surpasses the philosophic understanding that I believe Babbage had attained, a century earlier, of the universality of the planned (mechanical) Analytical Engine. Central to the Universal Turing Machine is the idea of having data, and input data in particular, represent a programme (called a "table" in Turing's paper).

(3) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

The main ingredient of the Enigma machine is a so-called rotor or hebern wheel. It is capable of rotating and it is wired so that the input alphabet is permuted (arranged) to give an output alphabet. The original Enigma machine had three rotors in it together with a reflector so that the plain language letter would come through three rotors, and then get reflected and come back through the same three rotors by a different route. Thus, for any fixed position of the rotors the original input alphabet would go through a succession of seven simple substitutions. Hence no letter could be enciphered as itself. But the whole effect of the machine was not merely a simple substitution since the wheels stopped in a certain way each time a letter was enciphered.

(4) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

Owing to the rule of secrecy known as the "need to know," which was applied fairly rigorously during the war, there is probably no one person who could give a reasonably comprehensive account of any large project at Bletchley. People who were not at the top did not know much about matters that were not directly of their concern, and the people who were at the top were not fully aware of what was going on because of the complexity of the work, the Advanced technology, the ingenuity, the mathematical ideas, and the variety of clinquish technical jargon.

(5) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

About two weeks before I went to Bletchley I met Milner-Barry at a chess match in London and asked him whether he was at Bletchley Park working on German ciphers. His reply was "No, my address is Room 47, Foreign Office, Whitehall." Two weeks later, when I joined Bletchley, I found he was head of a department called Hut 6, sure enough working on German ciphers. At first the official address at Bletchley was indeed Room 47, Foreign Office, Whitehall, London, but it soon became admissible to give one's private Bletchley address.

When I arrived at Bletchley I was met at the station by Hugh Alexander, the British chess champion. On the walk to the office Hugh revealed to me a number of secrets about the Enigma. Of course, we were not really supposed to talk about such things outside the precincts of the office. I shall never forget that sensational conversation.

(6) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

A number of scientists and mathematicians were on the so-called Reserve List and were not called up for military service. Perhaps the authorities remembered the poet Rupert Brooke and the physicist Henry Morley, who were both killed in World War I.

I believe the military mind in World War II was more enlightened about the use of trained minds.

(7) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

For the good of our morale, we were given a number of titbits about the results of our work. For example, we were told it had led directly to the sinking of the Bismarck. Also, there were times when Rommel did not receive any supplies in North Africa because all his supply ships were being sunk in consequence of our reading the Mediterranean Enigma. And obviously the reading of the U-boat traffic was tremendously valuable. Also, for the sake of our morale, we were once visited by Churchill, who delivered a pep talk to a little crowd of us gathered around him on the grass. Much later another pep talk was given by Field Marshal Alexander in a hall with an audience of about a thousand. At one point he obtained a laugh by mimicking one of Montgomery's gestures.

(8) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007)

The machine was programmed largely by plugboards. It read the tape at 5,000 characters per second and, at least in Mark II, the circuits were in quintuplicate so that in a sense the reading speed was 25,000 bits per second. This compares well with the speed of the electronic computers of the early 1950s. The first Colossus had 1,500 valves, which was probably far more than for any electronic machine previously used for any purpose. This was one reason why many people did not expect Colossus to work. But it was installed in December 1943 and began producing results almost immediately. Most of the failures of valves were caused by switching the machine on and off.

(9) Dan van der Vat, The Guardian (29th April 2009)

Irving John "Jack" Good, who has died aged 92, was a statistician and mathematical genius who, having shown his talent in childhood, made crucial contributions to the successful assault on German codes and ciphers at Bletchley Park during the second world war. Two decades later the director Stanley Kubrick called on him while making 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

On 27 May 1941, fresh from gaining his doctorate at Cambridge, Good walked into Hut Eight, scene of Bletchley Park's attack on German naval ciphers, for his first shift. This was the day that the Royal Navy caught, and destroyed, the battleship Bismarck after it had sunk HMS Hood, the British fleet flagship. Bletchley's contribution had been tangential but important: the discovery by wireless-traffic analysis that the German flagship was bound for Brest in France rather than Wilhelmshaven, from which she had set out, when signals to her started coming from the French port instead of the German one.

But Hut Eight had not been able to decipher in real time the 22 messages sent to the Bismarck because the Kriegsmarine was better at protecting its wireless traffic than the German army or the Luftwaffe, whose ciphers had been well penetrated the previous year. Naval signals were taking three to seven days to decipher, which usually made them operationally useless for the British. Yet this was about to change.

In his book Enigma: the Battle for the Code, Hugh Sebag-Montefiore describes how Good annoyed Alan Turing, the great mathematician and guiding intelligence of the Bletchley operation, by taking a nap on the floor of Hut Eight during his first night shift. Turing refused to speak to him afterwards - until the new boy used his statistical expertise to demonstrate how an essential trial-and-error method of attacking Enigma traffic could be accelerated .

The two men were thus reconciled. On another night shift, Good made a discovery missed by the old hands at Hut Eight. This helped them to work out which pairs of dummy letters the German encoders were adding to the twice enciphered, three-letter group at the start of each signal, telling the recipient how to set his machine to decipher it (for the British this became the achilles heel of the system). Good worked out that the "padding" was not random but came from a table, just as the setting itself did.

Some sensitive or important Enigma messages were enciphered twice, once in a special variation cipher and again in the normal cipher. Clearly a man who needed his sleep, Good dreamed one night that the process had been reversed: normal cipher first, special cipher second. When he woke up he tried his theory on an unbroken message - and promptly broke it. He also worked closely with Turing and others on the pioneering Colossus computers used to tackle other German ciphers. By now he was principal statistician.

Good was born Isidore Jacob Gudak to Polish-Jewish parents in London. His father was a watchmaker. He was educated at the Haberdashers' Aske's boys' school then in Hampstead, north London, where he effortlessly outpaced the mathematics teaching curriculum.

In 1938 he graduated with first-class honours in mathematics from Jesus College, Cambridge and stayed on to work for his PhD. While still at Cambridge, in 1941, he was approached by Bletchley recruiters. These included Hugh Alexander, twice British national chess champion, with whom he was to work closely, Good had won the 1939 Cambridgeshire chess championship. He reported for work within days. His service with Turing lasted nearly two years until he transferred to a team led by Max Newman, working on Colossus.

In 1947 Newman invited Good to join him and Turing at Manchester University. There for three years he lectured in mathematics and researched computers - including the Manchester Mark 1. Then, in 1948, he was recruited by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the successor to Bletchley Park, where he stayed until 1959. This did not prevent him from taking up a brief associate professorship at Princeton University and a short consultancy with IBM.

From 1959 until he moved to the US in 1967 he held various government-funded posts and a senior research fellowship at Trinity College, Oxford. He was made a doctor of science at Cambridge in 1963 and at Oxford in 1964. Three years later he was appointed professor of statistics at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

As the author of such treatises as Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine and Logic of Man and Machine (both 1965), Good must have seemed the obvious man for Kubrick to consult when making 2001; one of the main characters in the film is the super-computer HAL 9000, which shows intelligence and emotions but goes rogue. Good's published work ran to more than three million words.

Slender and sporting a bushy moustache, Good was not without humour. He published one paper under the names IJ Good and K Caj Doog, his own nickname spelt backwards. In one paper in 1988 he solemnly reviewed other writings on the subject, mainly his own, on the grounds that: "I have read them all carefully." In Virginia, where car owners can invent their own numberplates, he chose 007 IJG in a coy reference to his wartime intelligence role.

Irving John "Jack" Good, mathematician, born 9 December 1916; died 5 April 2009

References

(1) Dan van der Vat, The Guardian (29th April 2009)

(2) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) page 217

(3) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007) page 53

(4) Dan van der Vat, The Guardian (29th April 2009)

(5) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007) pages 73-74

(6) Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle For The Code (2004) page 217

(7) Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010) page 95

(8) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 55

(9) Harold Keen, interviewed by Anthony Cave Brown (c. 1970)

(10) Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies (1976) page 23

(11) Nigel Cawthorne, The Enigma Man (2014) page 58

(12) Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) page 231

(13) Mary Stewart, interviewed in the documentary The Men Who Cracked Enigma (2003)

(14) Dan van der Vat, The Guardian (29th April 2009)

(15) Jack Good, quoted by Michael Paterson, the author of Voices of the Codebreakers (2007) page 71

(16) Dan van der Vat, The Guardian (29th April 2009)