On this day on 6th April

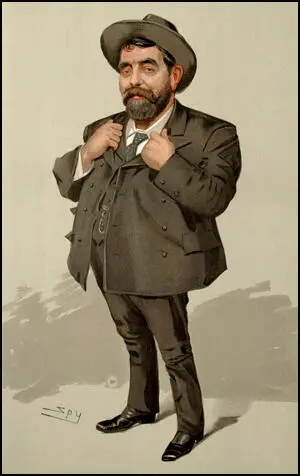

On this day in 1605 John Stowe died. John Stowe was born in in 1525. Stowe was a London tailor who was very interested in history. In 1565 he published a book that was a summary of the information that he could find in various chronicles written during the Middle Ages. This included The Summarie of Englyshe Chronicles, The Chronicles of England, The Annales of England and A Survey of London (1598).

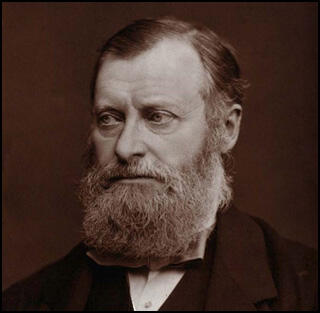

On this day in 1773 James Mill, the son of a shoemaker from Montrose, was born. He studied for the ministry at Edinburgh and was ordained in 1798. In 1802 Mill left the Church for journalism and after moving to London he began writing articles for the Edinburgh Review and the St. James Chronicle.

In London James Mill became a friend and disciple of Jeremy Bentham and fully supported his ideas on utilitarianism. Mill became a prominent member of the Philosophical Radicals, a group which included Bentham, David Ricardo, George Grote and John Austin.

In 1817 James Mill finished his major work, the History of British India. This book resulted in him being offered a position with the East India Company. Mill continued to write articles for newspapers and journals and in 1824 he joined Jeremy Bentham to help establish the Westminster Review.Mill's son, John Stuart Mill, also wrote for the Westminster Review and eventually became editor of the journal.

Mill wrote several important books including Elements of Political Economy (1821) and Analysis of the Phenomenon of the Human Mind (1829) where he attempted to provide a psychological basis for utilitarianism.

James Mill died on 23rd June 1836.

On this day in 1812 Alexander Herzen, the illegitimate son of Ivan Yakovlev, a wealthy member of the nobility, was born in Moscow, Russia. He was the heir to a considerable fortune. According to Isaiah Berlin: "Ivan Yakovlev, a rich and well-born Russian gentleman... a morose, difficult, possessive, distinguished and civilized man, who bullied his son, loved him deeply, embittered his life, and had an enormous influence upon him both by attraction and repulsion."

As a child he had deep sympathy for the serfs under the control of his father and uncle. Herzen explains in his autobiography, My Past and Thoughts (1867)" Neither my father nor my uncle was specially tyrannical, at least in the way of corporal punishment. My uncle, being hot-tempered and impatient, was often rough and unjust... A commoner form of punishment was compulsory enlistment in the Army, which was intensely dreaded by all the young men-servants. They preferred to remain serfs, without family or kin, rather than carry the knapsack for twenty years. I was strongly affected by those horrible scenes: at the summons of the land-owner, a file of military police would appear like thieves in the night and seize their victim without warning." These experiences developed in Herzen a deep sympathy for the peasants and became an advocate of social reform.

One of his tutors, Ivan Protopopov, introduced him to the work of Alexander Pushkin and Kondraty Ryleyev (a poet who had been executed for his role in the Decembrist Revolt that attempted to overthrow Tsar Nicholas I in 1825. "This man was full of that respectable indefinite liberalism, which, though it often disappears with the first grey hair, marriage, and professional success, does nevertheless raise a man's character... He began to bring me manuscript copies, in very small writing and very much frayed, of Pushkin's poems - Ode to Freedom, The Dagger, and of Ryleyev's Thoughts. These I used to copy out in secret."

In 1827 Alexander Herzen became friends with Nikolay Ogarev. Herzen commented in his autobiography: "I do not know why people dwell exclusively on recollections of first love and say nothing about memories of youthful friendship. First love is so fragrant, just because it forgets difference of sex, because it is passionate friendship. Friendship between young men has all the fervour of love and all its characteristics - the same shy reluctance to profane its feeling by speech, the same diffidence and absolute devotion, the same pangs at parting, and the same exclusive desire to stand alone without a rival."

Herzen was educated at the University of Moscow. He studied mathematics and physics: "I never had any great turn or much liking for mathematics, Nikolay and I were taught the subject by the same teacher, whom we liked because he told us stories; he was very entertaining, but I doubt if he could have developed a special passion in any pupil for his branch of science... I chose that Faculty, because it included the subject of natural science, in which I then took a specially strong interest."

While at university Herzen mixed in radical circles: "The pursuit of knowledge had not yet become divorced from realities, and did not distract our attention from the suffering humanity around us; and this sympathy heightened the social morality of the students. My friends and I said openly in the lecture-room whatever came into our heads; copies of forbidden poems were freely circulated, and forbidden books were read aloud and commented on; and yet I cannot recall a single instance of information given by a traitor to the authorities."

Afterwards he worked at a girls' school run by French Catholic priests. One of his students was the 12 year-old Tanya Passek. She later recalled how Herzen's teaching was a revelation. At her previous school her education consisted of reading "volumes of incomprehensible hieroglyphics, the coldness and severity of the teachers and the constant fear of punishment: having to wear a dunce's cap, or being led on a string around the building". Herzen introduced Passek to the poetry of Alexander Pushkin.

Herzen's outspoken views on the need to bring an end to serfdom and autocratic rule resulted in him being arrested and sent into internal exile. In 1835 he was forced to work as a government official in Vyatka (now Kirov). Later he moved to Vladimir, where he was appointed editor of the city's official gazette. After criticizing the police he was sentenced to two years exile in Novogorod.

Herzen became friends with, Mikhail Bakunin, Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Ogarev. As Cathy Porter, the author of Fathers and Daughters: Russian Women in Revolution (1976): "In the 1830s writers like Belinsky, Bakunin, Herzen and Ogarev, all consumed by the desire for philosophical certainties, were tentatively exploring the ideas of socialism within a framework of romantic culture.... Herzen's quasi-religious desire for inner peace prompted him to mediate between the more extreme philosophies of his friends. On the other hand there was Bakunin, whose radical interpretation of the theories of Fourier, Saint-Simon and Owen were to lead him to a more doctrinaire violence."

Another friend, Pavel Annenkov, commented: "I must own that I was puzzled and overwhelmed, when I first came to know Herzen - by this extraordinary mind which darted from one topic to another with unbelievable swiftness, with inexhaustible wit and brilliance; which could see in the turn of somebody's talk, in some simple incident, in some abstract idea, that vivid feature which gives expression and life. He had a most astonishing capacity for instantaneous, unexpected juxtaposition of quite dissimilar things, and this gift he had in a very high degree, fed as it was by the powers of the most subtle observation and a very solid fund of encyclopedic knowledge. He had it to such a degree that, in the end, his listeners were sometimes exhausted by the inextinguishable fireworks of his speech, the inexhaustible fantasy and invention, a kind of prodigal opulence of intellect which astonished his audience."

At the age of twenty-six he married his first cousin, Natalie Zakharina. In 1842 Herzen returned to Moscow and immediately joined those campaigning for reform. His wide-reading had radicalized him and he was now a supporter of the anarchist-socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Herzen believed that the peasants in Russia could become a revolutionary force and after the overthrow of the nobility would create a socialist society. This included the vision of peasants living in small village communes where the land was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines.

After receiving a large inheritance from his father, Herzen decided to leave Russia. He arrived in Paris in 1847 and witnessed the political struggles that resulted in the 1848 Revolution. His commentary on the failed European revolutions, From the Other Shore, was published in 1850. Herzen wrote: "In nature, as in the souls of men, there slumber endless possibilities and forces, and in suitable conditions... they develop, and will develop furiously. They may fill a world, or they may fall by the roadside. They may take a new direction. They may stop. They may collapse... Nature is perfectly indifferent to what happens... But then, you may ask, what is all this for?... To look at the end and not at the action itself is a cardinal error. Of what use to the flower is its bright magnificent bloom? Or this intoxicating scent, since it will only pass away?... None at all. But nature is not so miserly. She does not disdain what is transient, what is only in the present. At every point she achieves all she can achieve ... Who will find fault with nature because flowers bloom in the morning and die at night, because she has not given the rose or the lily the hardness of flint? And this miserable pedestrian principle we wish to transfer to the world of history... Life has no obligation to realise the fantasies and ideas of civilisation... Life loves novelty... History seldom repeats itself, it uses every accident, simultaneously knocks at a thousand doors... doors which may open... who knows?"

Herzen's biographer, Edward Acton, the author of Alexander Herzen and the Role of the Intellectual Revolutionary (1979) has argued: "One of the first members of the Russian intelligentsia to adopt socialism, he acknowledged a major debt to Fourier, the Saint-Simonians, Blanc and Proudhon. Initially he looked to the West to inaugurate an era of socialist justice and individual liberty. The failure of the Revolutions of 1848 affected him profoundly. His commentary on them, From the Other Shore (1850), ranks with those of Marx and Tocqueville. Its finest lines explored the tensions between an unqualified affirmation of the individual and the sacrifices demanded by the revolutionary cause."

In 1852 Alexander Herzen moved to London. The accession of Alexander II in 1855 gave Herzen hope that reform would take place in Russia and he established the Free Russian Press that published a series of journals including The Bell. Herzen predicted that because of its backward economy, socialism would be introduced into Russia before any other European country. "What can be accomplished only by a series of cataclysms in the West can develop in Russia out of existing conditions."

Herzen was joined in England by Mikhail Bakunin. The two men worked together on the journal until 1863 when Bakunin went to join the insurrection in Poland. The Bell was smuggled into Russia where it was distributed to those who favoured reform. According to Isaiah Berlin "Herzen... dealt with anything that seemed to be of topical interest. He exposed, he denounced, he derided, he preached, he became a kind of Russian Voltaire of the mid-nineteenth century. He was a journalist of genius, and his articles, written with brilliance, gaiety and passion, although, of course, officially forbidden, circulated in Russia and were read by radicals and conservatives alike."

Herzen's views expressed in the newspaper appeared fairly conservative to those embracing the ideas of revolutionary groups such as the People's Will and the Liberation of Labour. Herzen criticized the desire to impose a new system on the people arguing that the time had come to stop "taking the people for clay and ourselves for sculptors".

Herzen wrote that left-wing intellectuals should stop taking "the people for clay and ourselves for sculptors". On one occasion Louis Blanc, a committed socialist, said to Herzen that human life was a great social duty, that man must always sacrifice himself to society. Herzen asked him why? Blanc replied "Surely the whole purpose and mission of man is the well-being of society." Herzen retorted: "But it will never be attained if everyone makes sacrifices and nobody enjoys himself."

Herzen rejected the ideas of people like Karl Marx who promoted the idea that socialism was inevitable. As Isaiah Berlin points out: "The purpose of the struggle for liberty is not liberty tomorrow, it is liberty today, the liberty of living individuals with their own individual ends, the ends for which they move and fight and perhaps die, ends which are sacred to them. To crush their freedom, their pursuits, to ruin their ends for the sake of some vague felicity in the future which cannot be guaranteed, about which we know nothing, which is simply the product of some enormous metaphysical construction that itself rests upon sand, for which there is no logical, or empirical, or any other rational guarantee - to do that is in the first place blind, because the future is uncertain; and in the second place vicious, because it offends against the only moral values we know; because it tramples on human demands in the name of abstractions - freedom, happiness, justice - fanatical generalizations, mystical sounds, idolized sets of words."

In 1865 Herzen wrote: "Social progress is possible only under complete republican freedom, under full democratic equality. A republic that would not lead to Socialism seems an absurdity to us - a transitional stage regarding itself as the goal. On the other hand, Socialism which might try to dispense with political freedom would rapidly degenerate into an autocratic Communism." In another article he claimed: "Who will finish us off? The senile barbarism of the sceptre or the wild barbarism of communism, the bloody sabre, or the red flag? Communism will sweep across the world in a violent tempest - dreadful, bloody, unjust, swift."

Isaiah Berlin has argued: "The purpose of the struggle for liberty is not liberty tomorrow, it is liberty today, the liberty of living individuals with their own individual ends, the ends for which they move and fight and perhaps die, ends which are sacred to them. To crush their freedom, their pursuits, to ruin their ends for the sake of some vague felicity in the future which cannot be guaranteed, about which we know nothing, which is simply the product of some enormous metaphysical construction that itself rests upon sand, for which there is no logical, or empirical, or any other rational guarantee - to do that is in the first place blind, because the future is uncertain; and in the second place vicious, because it offends against the only moral values we know; because it tramples on human demands in the name of abstractions - freedom, happiness, justice - fanatical generalizations, mystical sounds, idolized sets of words."

Herzen believed that any socialist revolution in Russia would have to be instigated by the peasantry. According to Edward Acton: "Nineteenth-century Russia was overwhelmingly a peasant society, and it was to the peasantry that Herzen looked for revolutionary upheaval and socialist construction. Central to his vision was the existence of the Russian peasant commune. In most parts of the empire the peasantry lived in small village communes where the land was owned by the commune and was periodically redistributed among individual households along egalitarian lines. In this he saw the embryo of a socialist society. If the economic burdens of serfdom and state taxation were to be removed, and the land of the nobility made over to the communes, they would develop into flourishing socialist cells."

Acton goes on to argue: "The oppression of the central state could be done away with altogether and replaced by a socialist society of independent, egalitarian communes. There was no need for Russia to follow in the footsteps of the West, to pass through the purgatory of capitalist, industrial and urban development or of bourgeois constitutional government. She could benefit from her late arrival on the historical scene and avoid the mistakes of others." Herzen's ideas later inspired the formation of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Lenin was later to criticise the ideas of Herzen: "Herzen belonged to the generation of revolutionaries among the nobility and landlords of the first half of the last century.... His 'socialism' was one of the countless forms and varieties of bourgeois and petty-bourgeois socialism of the period of 1848, which were dealt their death-blow in the June days of that year. In point of fact, it was not socialism at all, but so many sentimental phrases, benevolent visions, which were the expression at that time of the revolutionary character of the bourgeois democrats, as well as of the proletariat, which had not yet freed itself from the influence of those democrats... Herzen’s spiritual shipwreck, his deep scepticism and pessimism after 1848, was a shipwreck of the bourgeois illusions of socialism. Herzen’s spiritual drama was a product and reflection of that epoch in world history when the revolutionary character of the bourgeois democrats was already passing away (in Europe), while the revolutionary character of the socialist proletariat had not yet matured."

Tom Stoppard has written about Herzen's relationship with Karl Marx: "Marx distrusted Herzen, and was despised by him in return. Herzen had no time for the kind of mono-theory that bound history, progress and individual autonomy to some overarching abstraction like Marx's material dialecticism. What he did have time for - and what bound Isaiah Berlin to him - was the individual over the collective, the actual over the theoretical. What he detested above all was the conceit that future bliss justified present sacrifice and bloodshed. The future, said Herzen, was the offspring of accident and wilfulness. There was no libretto or destination, and there was always as much in front as behind."

After the decline in popularity of The Bell, Herzen devoted his energies to My Past and Thoughts (1867). The book was a mixture of autobiography and an analysis of the social, political and ideological developments that had taken place during his life. Edward Acton has pointed out: "In its pages the pattern of his own life was skillfully woven into the fabric of political, social and ideological developments around him.... In fusing his personal experience with the history of an era, Herzen created a literary and political masterpiece which shows no signs of losing its force."

Alexander Herzen died in Paris on 21st January, 1870.

On this day in 1852 Will Crooks, the son of a ship's stoker, was born in a one-room house Poplar, East London. When he was three years old, William's father lost an arm when a ship's engine was started when he was oiling the machinery. Unable to find regular work because of his disablement, the family had to rely on the earnings of Mrs. Crooks work as a seamstress.

In 1861 Mr. Crooks and the five youngest children, including William, were forced to enter the Poplar Workhouse. Eventually Mrs. Crooks was able to find enough work and a cheaper room and the family were reunited. These experiences had a dramatic impact on Crooks and helped to influence his strong views on poverty and inequality.

Mrs. Crooks, despite being illiterate herself, encouraged her children to go to school. Although always short of money, Mrs. Crooks found the penny a week needed to educate William at George Green School on the East India Dock. She was also a deeply religious woman and the whole family attended the local Congregational Church.

As soon as he was old enough, William found work as a errand boy at a grocer's for two shillings a week. This was followed by a period as a blacksmith's labourer, but in 1866 Mrs. Crooks was able to arrange for the fourteen year old William to be apprenticed to a copper. Crooks was an avid reader and as a teenager discovered the works of Charles Dickens. He also began reading radical newspapers and found out about the campaigns of reformers such as John Bright and Richard Cobden.

Crooks impressed his fellow workers were impressed with his knowledge and asked him to speak to their boss about the excessive overtime they had to work. Crooks agreed to do this but as a result of the meeting he was sacked as a political agitator. Crooks, whose young wife had just had their first child, was forced to leave the area in search of work. Eventually Crooks found work in Liverpool. His family joined him but within a month his child died and Crooks and his wife returned to London.

Crooks found work as a casual labourer at East India Docks. Every Sunday morning he gave lectures on politics at the dock gates in Popular. Subjects of his lectures, at what became known as Crooks' College, included trade unionism, temperance and co-operative societies. John Robert Clynes later recalled: "Will Crooks combined the inspiration of a great evangelist with such a stock of comic stories, generally related as personal experiences, that his audience alternated between tears of sympathy and tears of laughter. I know of no stage comedian who can move his audience today to such roars of merriment as could Will Crooks, when he related the human incidents that formed so valuable a part of his platform stock. I once heard him say that a non-Union workman who tried to gain personal advancement at the expense of his mates was like a man who stole a wreath from his neighbour's grave and won a prize with it at a flower show!"

When the London Dock Strike started in August 1889, Crooks used his considerable skills as an orator to help raise funds for the dockers. Over the next few weeks Crooks emerged with Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the four main leaders of the strike. The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but other trade union activists such as Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands.

The London County Council (LCC) was created as a result of the 1888 Local Government Act. The LCC was the first metropolitan-wide form of general local government. Crooks became Progressive Party candidate for Poplar. Elections were held in January 1889 and the Progressive Party, won 70 of the 118 seats. Crooks won in Popular and other leaders of the labour movement including Sidney Webb John Burns and Ben Tillett, joined him in the LCC.

In 1892 Crooks' wife died, leaving him with six children. A year later he married Elizabeth Lake, a nurse from Gloucestershire. Crooks became chairman of the Public Control Committee and in this post promoted fair wages for LCC employees and the Infant Life Protection Bill which ended baby-farming in London. Crooks also became the first working-class member of the Poplar Board of Guardians.

Will Crooks became chairman of the Board of Guardians in 1897 and with the aid of his fellow member and friend, George Lansbury, began the task of reforming how the Popular Workhouse was run. Corrupt and uncaring officials were sacked, and the food and education that the inmates received were improved. Every effort was made to find homes for the young orphans in the workhouse. Crooks and Lansbury were so successful that the Poplar Workhouse became a model for other Poor Law authorities.

Crooks also became a member of the Poplar Borough Council and in 1901 became the first Labour mayor of London. He also helped establish the National Committee on Old Age Pensions. Influenced by the ideas first expressed by Tom Paine in The Rights of Man, Crooks believed that pensions were the only way to keep the elderly poor from entering the workhouse.

In 1903 the Labour Representation Committee invited Crooks to stand as their candidate in a by-election in Woolwich. Crooks had made many friends in the Liberal Party during his time on the London County Council and they withdrew their candidate from the election. During the campaign Crooks argued against the Taff Vale decision and the 1902 Education Act and urged the government to take measures to help the unemployed and those workers on low wages. Although normally a safe Conservative seat, the support of the Liberals enabled Crooks to obtain an easy victory.

After his election Crooks continued to live in his house in Poplar. He argued that it was important that he continued to retain his links with the working-class. In the House of Commons Crooks concentrated on the issue of unemployment. He supported the Unemployment Bill introduced by Arthur Balfour in 1905 and controversially advocated compulsory agricultural work for the able-bodied unemployed.

Crooks was re-elected in the 1906 General Election and for the next four years supported the reforming Liberal administrations led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1906-1908) and Herbert Asquith (1908-1910). Will Crooks was defeated in the January 1910 General Election but returned to the House of Commons in the election held in December, 1910.

Unlike most of the leaders of the Labour Party, Crooks enthusiastically supported Britain's involvement in the First World War. He participated in the recruiting campaign and toured the Western Front in an effort to boost the morale of troops. In one speech Crooks declared that he "would rather see every living soul blotted off the face of the earth than see the Kaiser supreme anywhere."

Will Crooks won the seat in the 1918 General Election but he was forced to retire from his seat in February 1921, due to ill-health. Will Crooks, who had never moved away from his house in Poplar, died in London Hospital, Whitechapel, on the 5th June, 1921.

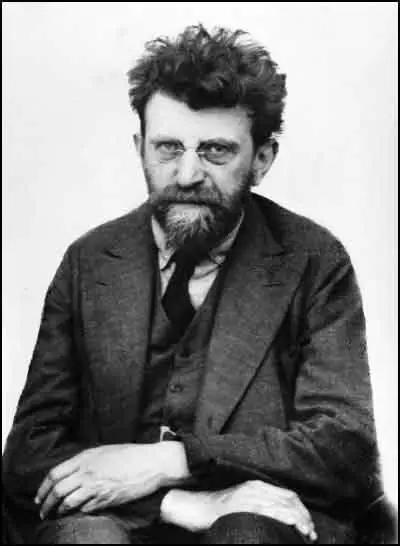

On this day in 1878 Erich Mühsam, the son of Siegfried Mühsam, a pharmacist, and Rosalie Seligmann, was born in Berlin on 6th April, 1878. His parents were orthodox Jews. Erich had three siblings Elisabeth Margarethe (1875), Hans Günther (1876) and Charlotte (1881). When Erich was one year old, the family moved to Lubeck, where the children were educated at local schools.

As a young man he had a strong desire to become a poet: " I was completely defined by my poetry, and if my poetry was all that I had to offer to the people, then I could write an autobiography that satisfies the simple needs of literary historians for classification... Early attempts at poetry with no support from school or parents. Poetry was seen as a distraction from duty and had to be pursued in secrecy."

Mühsam was expelled from school at the age of sixteen for "socialist agitation". According to the headmaster, Mühsam had leaked a speech of his to a socialist newspaper, Lübecker Volksboten (Messenger for the People): "As a consequence, the journal published a scandalous and disgraceful article about our school and a reprint of my speech, shortened, distorted, ridiculed, and with sardonic commentary - in truth, both the content and the form of the speech were noble, warm, and well measured. With this deceitful betrayal, Mühsam has placed himself beyond the school's boundaries and severed all ties with it."

Following his father's wishes, Mühsam became a pharmacist apprentice. Soon after the death of his mother, he moved to Berlin. He associated with other left-wing thinkers. This included the social reformer, Heinrich Hart, who encouraged him to follow his true passion, writing, even if it brought him into conflict with his father. According to another friend, Hart argued: "If you are not afraid of a little hunger and some missteps, then go ahead and do what you have to do! How can one discourage a man from doing what he wants to?"

Mühsam later argued: "Even at a young age, I realized that the state apparatus determined the injustice of all social institutions. To fight the state and the forms in which it expresses itself - capitalism, imperialism, militarism, class domination, political judiciary, and oppression of any kind - has always been the motivation for my actions. I was an anarchist before I knew what anarchism was. I became a socialist and communist when I began to understand the origins of injustice in the social fabric."

Mühsam was deeply influenced by the ideas of Gustav Landauer, a leading anarchist. "Landauer was an anarchist all his life. However, it would be utterly ridiculous to read his various ideas through the glasses of a specific anarchist branch, to praise or condemn him as an individualist, communist, collectivist, terrorist, or pacifist... Landauer, never saw anarchism as a politically or organizationally limited doctrine, but as an expression of ordered freedom in thought and action."

It has been argued that in the beginning, Mühsam, the younger and politically less experienced of the two, looked up to Landauer; a teacher-student dynamic long characterized their relationship. "However, Mühsam was clearly independent in his ideas and soon equaled Landauer in influence. Among the most notable differences between the two was Mühsam's openness to party communism, never shared by Landauer. There were also disparities in character: Landauer often appeared to be the philosopher and sage, while Mühsam was notoriously restless and temperamental... While Mühsam immersed himself passionately in debates about free love or the rights of homosexuals, Landauer remained cautious in these respects and always held on to marriage and family as important miniature examples of the communities on which to build a socialist society."

Another friend during this period was Rudolf Rocker. He later commented on Mühsam's personality: "There was something child-like and unconstrained, something joyful in this man; something that no personal sorrow, no misery could erase. With an almost lyrical passion, he believed in the proletariat... natural desire for freedom, and whenever I challenged this assumption, it deeply upset him.... Mühsam was a believer. His belief could move mountains. He was a poet to whom there was no clear difference between the reality of life and his dreams."

Augustin Souchy was another anarchist who appreciated Mühsam's talents: "He had a fascinating personality; he was spiritual, imaginative, witty, funny, and possessed a great sense of irony - at the same time he was kind, helpful, and emphatic... Erich had his heart in his hand, and comradeship in his blood." Mühsam also became friends with Frank Wedekind. One one occasion he said to Mühsam: "You always ride on two horses that pull in different directions. One day, they will tear your legs off!" Mühsam replied: "If I let go of one, I will lose my balance and break my neck."

In 1908 Mühsam and Gustav Landauer established Sozialistischer Bund in May 1908, with the stated goal of "uniting all humans who are serious about realizing socialism". Landauer and Mühsam hoped to inspire the creation of small independent cooperatives and communes as the basic cells of a new socialist society. To support the new organisation, Landauer revived Der Sozialist, describing it as the Journal of the Socialist Bund.

Chris Hirte has argued that the made a good combination: "To sit in a chamber and to dream of anarchist settlements, as Landauer did, was not Mühsam's way. He had to be in the midst of life; he had to be where life was at its most colorful, where things fermented and brewed." Other important members included Martin Buber and Margarethe Faas-Hardegger. At its height, they had around 800 people associated with the group. Landauer argued: "The difference between us socialists in the Socialist Bund and the communists is not that we have a different model of a future society. The difference is that we do not have any model. we embrace the future's openness and refuse to determine it. What we want is to realize socialism, doing what we can for its realization now."

According to Gabriel Kuhn: "There were a few points of contention. The most important concerned matters of family life and sexuality. Laudauer, who saw the nuclear family as the social core of mutual aid and solidarity, repeatedly drew the ire of Mühsam, who was a strong believer in free love and sexual experimentation. The conflict came to a head in 1910 over the publication of Landauer's article Tarnowska, a biting critique of free love, which Landauer saw as a mere pretext for moral and social degeneration. For a while, Mühsam even saw the friendship threatened, but the two soon managed to work out their differences."

Gustav Landauer also damaged his relationship with Margarethe Faas-Hardegger when he criticized her for an article questioning the nuclear family and arguing for communal child rearing. He admitted to Mühsam that "it has always been difficult for me to adopt and execute the ideas and plans for others". Mühsam pointed out: "Only those who see him as a determined and fearless fighter, kind, soft, and generous in everyday relations, but intolerant, hard, and head-strong to the point of arrogance in important issues, can understand him the way he really was."

In April 1911 Mühsam established the monthly magazine Kain-Zeitschrift für Menschlichkeit (Cain - Journal for Humanity). Virtually a one man operation, the socialist journal sold well enough to guarantee Mühsam a modest living. In its first edition Mühsam wrote: "This journal has been founded without capital. Not because of any principle, but because there was no capital." In his autobiography he pointed out that he was not just a journalist: "I did tedious political work like distributing leaflets and going door-to-door, and that I gave lectures at group meetings and speeches at large gatherings."

On the outbreak of the First World War Mühsam controversially commented: "I am united with all Germans in the wish that we can keep foreign hordes away from our women and children, away from our towns and fields." He later apologized to his friends and admitted that he had written the words "under the pressure of anxiety, fear, mental strain, and emotional turmoil." It was not long before Mühsam withdrew this statement and joined Gustav Landauer in anti-war activities.

Erich Mühsam led a very promiscuous life but he eventually became very close to Zenzl Elfinger, the daughter of an innkeeper. He wrote in his diary in December, 1914: "This morning, when she sat at my bed, I realized how dear she is to me. She comes close to what I most long for in a lover: a substitute for my mother. I can put my head in her lap and let her caress me quietly for hours. I don't feel the same with anyone else. Her love is extremely important to me, and I have to thank her more in these hard times than I sometimes realize myself. Maybe I can return some of this one day!"

In July 1915, Siegfried Mühsam died. They had a very poor relationship ever since Erich Mühsam abandoned his career as a pharmacist for the life of a writer, bohemian, and political activist, but he still believed he would inherit enough money to fell financially secure. This did not happen and he wrote in his diary: "Now the whole misery starts anew - the only difference being that I will no longer be able to borrow money in the name of an impending inheritance."

In September, 1915, Erich Mühsam married Zenzl Elfinger. Despite his ongoing promiscuity and related problems, she remained his lifelong companion. As a result of his anti-war activities, Mühsam was banished from Munich on 24th April 1918, to a small Bavarian town of Traunstein. On 28th October, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany.

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a Council Republic. Eisner's program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. Mühsam immediately returned to Munich to take part in the revolution. Other socialists who returned to the city included Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds."

In Bavaia, Kurt Eisner formed a coalition with the German Social Democrat Party (SDP) in the National Assembly. The Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) only received 2.5% of the total vote and he decided to resign to allow the SDP to form a stable government. He was on his way to present his resignation to the Bavarian parliament on 21st February, 1919, when he was assassinated in Munich by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley.

It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land." Johannes Hoffmann, of the SDP, replaced Eisner as President of Bavaria. One armed worker walked into the assembled parliament and shot dead one of the leaders of the Social Democratic Party. Many of the deputies fled in terror from the city.

Max Levien, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), became the new leader of the revolution. Rosa Levine-Meyer argued: "Levien.... was a man of great intelligence and erudition and an excellent speaker. He exercised an enormous appeal of the masses and could, with no great exaggeration, be defined as the revolutionary idol of Munich. But he owed his popularity rather to his brilliance and wit than to clear-mindedness and revolutionary expediency."

On 7th April, 1919, Levien declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. A fellow revolutionary, Paul Frölich later commented: "The Soviet Republic did not arise from the immediate needs of the working class... The establishment of a Soviet Republic was to the Independents and anarchists a reshuffling of political offices... For this handful of people the Soviet Republic was established when their bargaining at the green table had been closed... The masses outside were to them little more than believers about to receive the gift of salvation from the hands of these little gods. The thought that the Soviet Republic could only arise out of the mass movement was far removed from them. While they achieved the Soviet Republic they lacked the most important component, the councils."

Ernst Toller, a member of the Independent Socialist Party, became a growing influence in the revolutionary council. Rosa Levine-Meyer claimed that: "Toller was too intoxicated with the prospect of playing the Bavarian Lenin to miss the occasion. To prove himself worthy of his prospective allies, he borrowed a few of their slogans and presented them to the Social Democrats as conditions for his collaboration. They included such impressive demands as: Dictatorship of the class-conscious proletariat; socialization of industry, banks and large estates; reorganization of the bureaucratic state and local government machine and administrative control by Workers' and Peasants' Councils; introduction of compulsory labour for the bourgeoisie; establishment of a Red Army, etc. - twelve conditions in all."

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982) has pointed out: "Meanwhile, conditions for the mass of the population were getting worse daily. There were now some 40,000 unemployed in the city. A bitterly cold March had depleted coal stocks and caused a cancellation of all fuel rations. The city municipality was bankrupt, with its own employees refusing to accept its paper currency."

Eugen Levine, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), arrived in Munich from Berlin. The leadership of the KPD was determined to avoid any repetition of the events in Berlin in January, when its leaders, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches, were murdered by the authorities. Levine was instructed that "any occasion for military action by government troops must be strictly avoided". Levine immediately set about reorganizing the party to separate it off clearly from the anarcho-communists led by Erich Mühsam and Gustav Landauer. He reported back to Berlin that he had about 3,000 members of the KPD under his control. In a letter to his wife he commented that "in a few days the adventure will be liquidated".

Levine pointed out that despite the Max Levien declaration, little had changed in the city: "The third day of the Soviet Republic... In the factories the workers toil and drudge as ever before for the capitalists. In the offices sit the same royal functionaries. In the streets the old armed guardians of the capitalist world keep order. The scissors of the war profiteers and the dividend hunters still snip away. The rotary presses of the capitalist press still rattle on, spewing out poison and gall, lies and calumnies to the people craving for revolutionary enlightenment... Not a single bourgeois has been disarmed, not a single worker has been armed." Levine now gave orders for over 10,000 rifles to be distributed.

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly."

Erich Mühsam was arrested and sentenced to fifteen years of confinement in a fortress. A few weeks later, the Weimar Republic was established, giving Germany a parliamentarian constitution. Gabriel Kuhn has argued: "Being confined in a fortress - a sentence usually reserved for political dissidents - meant certain privileges compared to the general prison population, most notably the opening of cells for communal meetings and activities during the day, but it also meant increased harassment, reaching from the confiscation of papers and diaries to punishments like isolation and food deprivation. Mühsam's health deteriorated drastically during those years."

While in prison Mühsam briefly joined the German Communist Party (KPD). He explained in a letter to a friend, Martin Andersen Nexø: "I recently joined the Communist Party - of course not to follow the party line, but to be able to work against it from the inside." He also praised Lenin and the Bolsheviks but left the KPD when he heard about how the anarchists were being treated in Russia.

Erich Mühsam was released from prison on 20th December, 1924. He was greeted by a large gathering of sympathizers when he arrived in Berlin. The scene was later described by the journalist, Bruno Frei: "Thanks to my press card I was able to get past the police barriers. Helmet-wearing security forces, both on foot and on horses, had sealed off the station. On the square in front of it, there were several hundred, maybe a thousand workers and youths with flags and banners. Their republican deed: to greet Erich Mühsam! When the express train from Munich arrived, a few youngsters managed to make their way into the arrival hall. Mühsam stepped out of the train in obvious pain, accompanied by his wife Zenzl. The young workers lifted him on their shoulders.... Mühsam fought back tears and thanked the comrades. Someone started to sing The Internationale. At that very moment, the helmet-wearing mob attacked the people who had gathered around Mühsam. They yelled at them, pushed them, and hit them with batons. The comrades resisted courageously, though, protected Mühsam, and led him outside. Unfortunately, the police had already begun to chase the workers from the square.... Many were arrested and wounded."

Mühsam established the United Front of the Revolutionary Proletariat but it eventually collapsed for lack of support. He also worked with the Federation of Communist Anarchists of Germany (FKAD) but in 1925 he was expelled for carrying out "open propaganda in the interests the Communist Party" that was "not compatible with fundamental anarchist principles". Mühsam retaliated by saying that he was "an anarchist without always agreeing with the ideology and tactics of the majority of German anarchists."

In October 1926 he started the journal Fanal. He argued that there was the need for a revolutionary journal that dealt with the political significance of theatre and of the arts in general. The first edition was completely written by Mühsam: "There will be no contributions from others. I was in Bavarian captivity for almost six years and practically prohibited from presenting my thoughts to a wider public... People ought to grant me the modest sixteen pages I intend to fill every month, so that finally I can propagate ideas that no one else will print."

Mühsam promoted the work of left-wing artists and writers such as Bertolt Brecht, Ernst Toller, George Grosz, John Heartfield and Erwin Piscator: "Agitational art is good and necessary. It is needed by the proletariat both in revolutionary times and in the present. But it has to be art, skilled, spirited, and glittering. All arts have agitational potential, but none more than drama, In the theatre, living people present living passion. Here, more than anywhere else, true art can communicate true conviction. Here, the idea of a revolutionary worker can be materialized.... Arts must inspire people, and inspiration comes from the spirit. It is not our task to teach the minds of the workers with the help of the arts - it is our task to bring spirit to the minds of the workers with the help of the arts, as the spirit of the arts knows no limits. Neither dialectics nor historical materialism have anything to do with this; the only art that can enthuse and enflame the proletariat is the one that derives its richness and its fire from the spirit of freedom."

Mühsam was an effective public speaker. Fritz Erpenbeck has argued: "He (Mühsam) was able to capture the masses. He spoke with real passion and appealed to the people's feelings... He described events with such involvement that it felt real people believed him." Rudolf Rocker wrote: "As a human being, Mühsam was one of the most beautiful people I have ever met. He belonged to no party, which means that the humanity in him had not been destroyed, as in so many others. He was always noble in his conduct, a loyal and dedicated friend, and an enormously thoughtful and entertaining host."

After Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, Mühsam campaigned against the Nazi Party. He was arrested on 28th February, 1934 and was sent to a concentration camp in Oranienburg. His friend, Alexander Berkman, published details of his predicament: "I received a note from Germany yesterday. Erich Mühsam, the idealist, revolutionary, and Jew, represents everything that Hitler and his followers hate. They are attempting to destroy cultural and progressive life in Germany by destroying him. Mühsam became a particular object of Hitler's scorn because of his outstanding role in the Munich Revolution, alongside men like Landauer, Levine, and Toller."

A fellow prisoner later recalled how Mühsam was regularly beaten: "Erich staggered, tripped over a bank, and fell on some straw mattresses. The wardens jumped after him, striking more blows. We stood still, clenching our fists and grinding our teeth, condemned to watch. We knew from experience that the slightest sign of resistance would send us to the hole for fourteen days or straight to the medical ward. Finally, the wardens pulled Erich up again and taunted him... They hit Erich again with their fists. He fell back onto the straw mattresses, the wardens followed and continued to hit and kick him."

Another prisoner, John Stone, described how Erich Mühsam was murdered on 10th July, 1934: "In the evening, Mühsam was ordered to see the camp's commanders. When he returned, he said, They want me to hang myself - but I will not do them the favor. We went to bed at 8 p.m., as usual. At 9 p.m., they called Mühsam from his cell. This was the last time we saw him alive. It was clear that something out of the ordinary was happening. We were not allowed to go to the latrines in the yard that night. The next morning, we understood why: we found Mühsam's battered corpse there, dangling from a rope tied to a wooden bar. Obviously, the scene was supposed to look like a suicide. But it wasn't. If a man hangs himself, his legs are stretched because of the weight, and his tongue sticks out of his mouth. Mühsam's body didn't show any of these signs. His legs were bent. Furthermore, the rope was attached to the bar by an advanced bowline knot. Mühsam knew nothing about these things and would have been unable to tie it. Finally, the body showed clear indications of recent abuse. Mühsam had been beaten to death before he was hanged."

Zenzl Mühsam confirmed the death of her husband to his friend, Rudolf Rocker: "I have to talk to you. On July 16, my Erich was buried at Waldfriedhof Dahlem. I was not allowed to go to the funeral, because my relatives were afraid. I was the only living witness, apart from his comrades in prison, who saw him being tortured. I have seen Erich dead, my dear. He looked so beautiful. There was no fear on his face; his cold hands were so gorgeous when I kissed them goodbye. Every day it becomes clearer to me that I will never talk to Erich again. Never. I wonder if anyone in this world can comprehend this? I am in Prague with friends now. I have not found real peace yet, although I am tired, very tired. Money is a problem. For now, I must remain here. The authorities, the police etc. are very good to me."

On this day in 1862 the Battle of Shiloh took place. In February, 1862 Ulysses S. Grant took his army along the Tennessee River with a flotilla of gunboats and captured Fort Henry. This broke the communications of the extended Confederate line and Joseph E. Johnston decided to withdraw his main army to Nashville. He left 15,000 men to protect Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River but this was not enough and Grant had no difficulty taking this prize as well. With western Tennessee now secured, Abraham Lincoln was now able to set up a Union government in Nashville by appointing Andrew Johnson as its new governor.

After capturing Fort Donelson, Ulysses S. Grant advanced up the Tennessee River and established the headquarters of the Army of Tennessee at Savannah. Grant then arranged for his troops to join with Army of the Ohio, led by General Don Carlos Buell. General Albert S. Johnston decided to defeat Grant before Buell arrived.

On 6th April, Albert S. Johnston and Pierre T. Beauregard and 55,000 members of the Confederate Army attacked Grant's army near Shiloh Church, in Hardin, Tennessee. Taken by surprise, Grant's army suffered heavy losses until the arrival of General Don Carlos Buell and reinforcements the following day.

During the fighting Albert S. Johnston was killed and the new commander, Pierre T. Beauregard, decided to retreat to Corinth, Mississippi. Shiloh was the greatest battle so far of the Civil War. The Union Army suffered 13,000 casualties and the Confederate Army lost 10,000. These figures were questioned by Ulysses S. Grant who claimed that Confederates lost many more than he did.

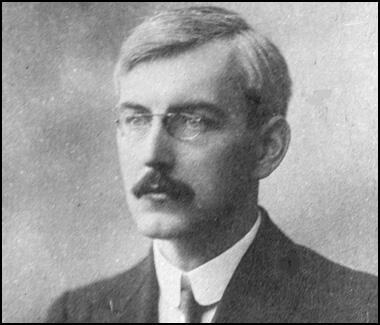

On this day in 1876 journalist Harold Williams, the son of a Nonconformist minister from England, was born on 6th April, 1876, in Auckland, New Zealand. His father also edited the Methodist Times. An extremely intelligent student, he was an outstanding linguist, and it was said that eventually he was able to speak twenty-five languages.

After briefly studying at Auckland University he entered the Methodist Ministry. Inspired by the writings of Leo Tolstoy, he became a vegetarian, pacifist, socialist and was a proponent of "the doctrine of Christian Anarchism." Eugene Grayland has argued: "His clerical superiors distrusted his views and disapproved of some of the heterodox books in his library, touching on evolution and such matters."

In 1900 he left New Zealand and went to Munich University where he studied philology, ethnology, philosophy, history and literature. He taught English part-time and received his Ph.D. in languages in 1903. Williams also began working as a journalist for The Times. He also worked for the Manchester Guardian and the Morning Post in Russia. While in the country he met Ariadna Tyrkova, a Constitutional Democrat Party member of the Duma. The couple were married in 1906.

As well as his journalistic work, Williams wrote Russia of the Russians (1914). H. G. Wells argued in the Daily News: "In a series of brilliant chapters, Doctor Williams has given as complete and balanced an account of present-day Russia as any one could desire... I could go on, sitting over this book and writing about it for days ... it is the most stimulating book upon international relations and the physical and intellectual being of a state that has been put before the English reader for many years."

Williams met Arthur Ransome in 1914. Ransome later commented: "He (Williams) opened doors for me that I might have been years in finding for myself... I owe him more than I can say." People he was introduced to included Sir George Buchanan, Bernard Pares, Paul Milyukov and Peter Struve. According to Roland Chambers, the author of The Last Englishman: The Double Life of Arthur Ransome (2009): Williams had a major influence on Ransome: "A shy, generous man a few years older than himself, with a pedagogic streak and a disarming stutter. Ransome benefited from Williams's encyclopedic knowledge of Russian history, his journalistic contacts and also from a friendship with Williams's wife, Ariadna Tyrkova, the first female representative elected to the Russian parliament, or State Duma, and a passionate advocate of constitutional reform. In Williams's company Ransome discussed not only politics, but philosophy, history and literature, sought out his advice on every subject and listened in amazement as he spoke in any one of the forty-two different languages used in Russia at that time."

On the outbreak of the First World War he was employed by the Daily Chronicle. His knowledge of the political situation was highly valued and he became an unofficial adviser to George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia and Bernard Pares, British Military Observer to the Russian Army. He warned them that discontent was growing and their was a danger that the people would rebel against Tsar Nicholas II.

In February 1917, he wrote: "All attention here is concentrated on the food question, which for the moment has become unintelligible. Long queues before the bakers' shops have long been a normal feature of life in the city. Grey bread is now sold instead of white, and cakes are not baked. Crowds wander about the streets, mostly women and boys, with a sprinkling of workmen. Here and there windows are broken and a few bakers' shops looted. But, on the whole, the crowds are remarkably good-tempered and presently cheer the troops, who are patrolling the streets."

Williams interviewed Alexander Kerensky in March, 1917: "Kerensky is a young man in his early thirties, of medium height, with a slight stoop, and a quick, alert movement, with brownish hair brushed straight up, a broad forehead already lined, a sharp nose, and bright, keen eyes, with a certain puffiness in the lids due to want of sleep, and a pale, nervous face tapering sharply to the chin. His whole bearing was that of a man who could control masses. He was dressed in a grey, rather worn suit, with a pencil sticking out of his breast pocket. He greeted us with a very pleasant smile, and his manner was simplicity itself. He led us into his study, and there we talked for an hour. We discussed the situation thoroughly, and I got the impression that Kerensky was not only a convinced and enthusiastic democrat, ready to sacrifice his life if need be for democracy - that I already knew from previous acquaintance - but that he had a clear, broad perception of the difficulties and dangers of the situation, and was preparing to meet them."

Williams welcomed the overthrow of Nicholas II: "It is a wonderful thing to see the birth of freedom. With freedom comes brotherhood, and in Petrograd today there is a flow of brotherly feeling. Everywhere you see it in the streets. The trams are not yet running, and people are tired of endless walking. But the habit now is to share your cab with perfect strangers. The police have gone, but the discipline is marvelous. Everyone shares the task of maintaining discipline and order. A volunteer militia has been formed and 7,000 men enrolled as special constables, mostly students, professors, and men of the professional classes generally. These, with the help of occasional small patrols of soldiers, control the traffic, guard the banks, factories, and Government buildings, and ensure security."

Williams rejected the idea that Vladimir Lenin could play an important role in affairs: "Lenin, leader of the extreme faction of the Social Democrats, arrived here on Monday night by way of Germany. His action in accepting from the German government a passage from Switzerland through Germany arouses intense indignation here. He has come back breathing fire, and demanding the immediate and unconditional conclusions of peace, civil war against the army and government, and vengeance on Kerensky and Chkheidze, whom he describes as traitors to the cause of International Socialism. At the meeting of Social Democrats yesterday his wild rant was received in dead silence, and he was vigorously attacked, not only by the more moderate Social Democrats, but by members of his own faction. Lenin was left absolutely without supporters. The sharp repulse given to this firebrand was a healthy sign of the growth of practical sense of the Socialist wing, and the generally moderate and sensible tone of the conference of provincial workers' and soldiers' deputies was another hopeful indication of the passing of the revolutionary fever."

On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. Williams wrote in the Daily Chronicle: "The composition of the new government is extraordinarily moderate in the circumstances. There has been, and still is, danger from extremists, who want at once to turn Russia into a Socialist republic and have been agitating amongst soldiers, but reason has been reinforced by a sense of danger from the Germans and the lingering forces of reaction gaining the upper hand."

Williams believed that the Kornilov Revolt dramatically changed the situation and dramatically increased the influence of the Bolsheviks: "The Kornilov Affair has intensified mutual distrust and completed the work of destruction. The Government is shadowy and unreal, and what personality it had has disappeared before the menace of the Democratic Assembly. Whatever power there is again concentrated in the hands of the Soviets, and, as always happens when the Soviets secure a monopoly of power, the influence of the Bolsheviks has increased enormously. Kerensky has returned from Headquarters, but his prestige has declined, and he is not actively supported either by the right or by the left."

Alexander Kerensky was now in danger and was forced to ask the Soviets and the Red Guards to protect Petrograd. The Bolsheviks, who controlled these organizations, agreed to this request, but Lenin made clear they would be fighting against Lavr Kornilov rather than for Kerensky. Within a few days the Bolsheviks had enlisted 25,000 armed recruits to defend Petrograd. While they dug trenches and fortified the city, delegations of soldiers were sent out to talk to the advancing troops. Meetings were held and Kornilov's troops decided not to attack Petrograd. General Krymov committed suicide and Kornilov was arrested and taken into custody.

Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin now urged the overthrow of the Provisional Government. On the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks began to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The Winter Palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. the Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace.

The attacks on the Winter Palace caused little damage but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the building and arrested the Cabinet ministers. Albert Rhys Williams reported: "A terrible lust lays hold of the mob - the lust that ravishing beauty incites in the long starved and long denied - the lust of loot. Even we, as spectators, are not immune to it. It burns up the last vestige of restraint and leaves one passion flaming in the veins - the passion to sack and pillage. Their eyes fall upon this treasure-trove, and their hands follow."

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Vladimir Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Felix Dzerzhinsky (Internal Affairs), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War).

A total of 703 candidates were elected to the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. This included Socialist Revolutionaries (299), Bolsheviks (168), Mensheviks (18) and Constitutional Democratic Party (17). The Bolsheviks were bitterly disappointed with the result as they hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the Socialist Revolutionaries, was elected President. When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups were banned in Russia.

Harold Williams wrote in the Daily Chronicle: "If you lived here you would feel in every bone of your body, in every fibre of your spirit, the bitterness of it... I cannot tell you all the brutalities, the fierce excesses, that are ravaging Russia from end to end and more ruthlessly than any invading army. Horrors pall on us - robbery, plunder and the cruellest forms of murder are grown a part of the very atmosphere we live in. It is worse than Tsarism ... The Bolsheviks do not profess to encourage any illusions as to their real nature. They treat the bourgeoisie of all countries with equal contempt; they glory in all violence directed against the ruling classes, they despise laws and decencies that they consider effete, they trample on the arts and refinements of life. It is nothing to them if in the throes of the great upheaval the world relapses into barbarism."

Harold Williams and Ariadna Tyrkova now fled the country. In 1921, Wickham Steed, the editor of The Times, offered Williams a position as a leader writer. In May 1922, he was appointed foreign editor. He held this position until his death on 18th November, 1928. Ariadna published a biography of her husband, Cheerful Giver, in 1935.

On this day in 1876 political activist John Scurr was born in Brisbane. He was adopted by his uncle and brought to London later that year. Scurr grew up in Poplar and worked as a clerk and married Julia Scurr in Woolwich in 1899. The couple had two sons and a daughter.

in 1902, joined the Social Democratic Federation. Other members of the SDF included H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Helen Taylor, Guy Aldred, John Spargo and Ben Tillett.

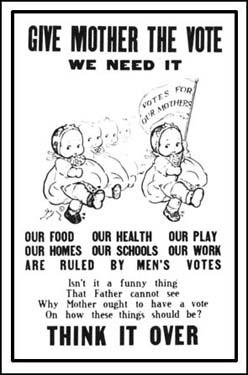

In February 1914 John and Julia Scurr became members of the United Suffragists. The group were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form a new organisation. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Edith Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett and Laurence Housman.

In November 1919 John Scurr was elected to Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison.

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including John Scurr and George Lansbury, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council was forced to back down and on 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

In the 1923 General Election, John Scurr, Susan Lawrence and George Lansbury were all elected to the House of Commons. The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated."

Julia Scurr died in 1927 at the age of 57. George Lansbury wrote that he had no doubt that the period of imprisonment, and the treatment she received, was directly responsible for her death.

Scurr regained his Mile End seat at the 1929 General Election. The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. In January 1929, 1,433,000 people were out of work, a year later it reached 1,533,000. By March 1930, the figure was 1,731,000. In June it reached 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. That month MacDonald invited a group of economists, including John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole and Walter Layton, to discuss this problem. However, he rejected all those ideas that involved an increase in public spending.

In March 1931 Ramsay MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problems. The committee included two members that had been nominated from the three main political parties. At the same time, John Maynard Keynes, the chairman of the Economic Advisory Council, published his report on the causes and remedies for the depression. This included an increase in public spending and by curtailing British investment overseas.

Philip Snowden rejected these ideas and this was followed by the resignation of Charles Trevelyan, the Minister of Education. "For some time I have realised that I am very much out of sympathy with the general method of Government policy. In the present disastrous condition of trade it seems to me that the crisis requires big Socialist measures. We ought to be demonstrating to the country the alternatives to economy and protection. Our value as a Government today should be to make people realise that Socialism is that alternative."

When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it forecast a huge budget deficit of £120 million and recommended that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. The two Labour Party nominees on the committee, Arthur Pugh and Charles Latham, refused to endorse the report.

The cabinet decided to form a committee consisting of Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Arthur Henderson, Jimmy Thomas and William Graham to consider the report. On 5th August, John Maynard Keynes wrote to MacDonald, describing the May Report as "the most foolish document I ever had the misfortune to read." He argued that the committee's recommendations clearly represented "an effort to make the existing deflation effective by bringing incomes down to the level of prices" and if adopted in isolation, they would result in "a most gross perversion of social justice". Keynes suggested that the best way to deal with the crisis was to leave the Gold Standard and devalue sterling. Two days later, Sir Ernest Harvey, the deputy governor of the Bank of England, wrote to Snowden to say that in the last four weeks the Bank had lost more than £60 million in gold and foreign exchange, in defending sterling. He added that there was almost no foreign exchange left.

Philip Snowden presented his recommendations to the MacDonald Committee that included the plan to raise approximately £90 million from increased taxation and to cut expenditure by £99 million. £67 million was to come from unemployment insurance, £12 million from education and the rest from the armed services, roads and a variety of smaller programmes. Arthur Henderson and William Graham rejected the idea of the proposed cut in unemployment benefit and the meeting ended without any decisions being made.

Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Susan Lawrence both decided to resign from the government if the cuts to the unemployment benefit went ahead: Pethick-Lawrence wrote: "Susan Lawrence came to see me. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, she was concerned with the proposed cuts in unemployment relief, which she regarded as dreadful. We discussed the whole situation and agreed that, if the Cabinet decided to accept the cuts in their entirety, we would both resign from the Government."

Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V about the economic crisis on 23rd August. He warned the King that several Cabinet ministers were likely to resign if he tried to cut unemployment benefit. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "King most friendly and expressed thanks and confidence. I then reported situation and at end I told him that after tonight I might be of no further use, and should resign with the whole Cabinet.... He said that he believed I was the only person who could carry the country through."

According to Harold Nicolson, the King decided to consult the leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties. Herbert Samuel told the King that he should try and persuade MacDonald to make the necessary economies. Stanley Baldwin agreed and said he was willing to serve under MacDonald in a National Government.

After another Cabinet meeting where no agreement about how to deal with the economic crisis could be achieved, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to resign. Sir Clive Wigram, the King's private secretary, later recalled that George V "impressed upon the Prime Minister that he was the only man to lead the country through the crisis and hoped that he would reconsider the situation." At a meeting with Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain and Herbert Samuel MacDonald told them that if he joined a National Government it "meant his death warrant". According to Chamberlain he said "he would be a ridiculous figure unable to command support and would bring odium on us as well as himself."

On 24th August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald returned to the palace and told the King that he had the Cabinet's resignation in his pocket. The King replied that he hoped that MacDonald "would help in the formation of a National Government." He added that by "remaining at his post, his position and reputation would be much more enhanced than if he surrendered the Government of the country at such a crisis." Eventually, he agreed to form a National Government.

The Labour Party was appalled by what they considered to be MacDonald's act of treachery. Arthur Henderson commented that MacDonald had never looked into the faces of those who had made it possible for him to be Prime Minister.

On 8th September 1931, the National Government's programme of £70 million economy programme was debated in the House of Commons. This included a £13 million cut in unemployment benefit. Tom Johnson, who wound up the debate for the Labour Party, declared that these policies were "not of a National Government but of a Wall Street Government". In the end the Government won by 309 votes to 249, but only 12 Labour M.P.s voted for the measures.

On 26th September, the Labour Party National Executive decided to expel all members of the National Government including Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey. As David Marquand has pointed out: "In the circumstances, its decision was understandable, perhaps inevitable. The Labour movement had been built on the trade-union ethic of loyalty to majority decisions. MacDonald had defied that ethic; to many Labour activists, he was now a kind of political blackleg, who deserved to be treated accordingly."

The 1931 General Election was held on 27th October, 1931. MacDonald led an anti-Labour alliance made up of Conservatives and National Liberals. It was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. John Scurr also lost his seat in Mile End. John Scurr died on 10th July, 1932.

On this day in 1882 Rose Schneiderman, the daughter of Jewish parents, was born in Saven, Poland. When Rose was eight years old her family emigrated to the United States. After the death of her father, Rose and her brothers and sisters were brought up in various orphanages.

At thirteen Rose was forced to go out to work: "I got a place in Hearn's as cash girl, and after working there three weeks changed to Ridley's, where I remained for two and a half years. I finally left because the pay was so very poor and there did not seem to be any chance of advancement, and a friend told me that I could do better making caps."

She eventually went to work in a factory in search of higher wages: "After I had been working as a cap maker for three years it began to dawn on me that we girls needed an organization. The men had organized already, and had gained some advantages, but the bosses had lost nothing, as they took it out on us. Finally Miss Brout and I and another girl went to the National Board of United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers when it was in session, and asked-them to organize the girls. Then came a big strike. About 100 girls went out. The result was a victory, which netted us - I mean the girls - $2 increase in our wages on the average."