Eldridge Cleaver

Eldridge Cleaver, the son of a nightclub piano player, was born in Wabbaseka, Arkansas, in 1935. The family later moved to Los Angeles. As a teenager he was sent to reform school for stealing a bicycle and selling marijuana.

Soon after his release he was arrested for possession of marijuana. Found guilty he was sentenced to 30 months in Soledad Prison. While in prison Cleaver became interested in politics and read the works of Karl Marx, Tom Paine, William Du Bois and Lenin.

Cleaver was released in 1957 but the following year he was arrested and charged with attempted murder. Found guilty, he was sentenced to a term of two to fourteen years in prison. While in San Quentin he began reading books on black civil rights and was particularly influenced by the writings of Malcolm X.

After leaving prison in 1966 Cleaver joined the Black Panther Party (BPP). Soon afterwards he was appointed the organization's minister of information. Cleaver was now a committed revolutionary and called for an armed insurrection and the establishment of a black socialist government.

Cleaver married Kathleen Neal on 27th December, 1967. The following year he published his memoirs, Soul on Ice (1968), established him as one of African American's the most important political figures.

The activities of the Black Panthers came to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Hoover described the Panthers as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" and ordered the FBI to employ "hard-hitting counter-intelligence measures to cripple the Black Panthers".

On 6th April, 1968 eight BPP members, including Cleaver, Bobby Hutton and David Hilliard, were travelling in two cars when they were ambushed by the Oakland police. Cleaver and Hutton ran for cover and found themselves in a basement surrounded by police. The building was fired upon for over an hour. When a tear-gas canister was thrown into the basement the two men decided to surrender. Cleaver was wounded in the leg and so Hutton said he would go first. When he left the building with his hands in the air he was shot twelve times by the police and was killed instantly.

Cleaver was arrested and charged with attempted murder. He was given bail and in November, 1968, he fled to Mexico. Later he moved to Cuba. He also spent time in Algeria.

While in exile Cleaver had disagreements with Huey Newton and in 1971 he expelled him from the Black Panther Party. Soon afterwards Cleaver formed the Revolutionary Peole's Communication Network and Kathleen Cleaver returned to the United States to establish the party in New York.

Soon afterwards Cleaver underwent a mystical conversion to Christianity. He now rejected his former political beliefs describing the system in Cuba as "voodoosocialism". He also wrote an article for the New York Times where he argued "With all its faults, the American political system is the freest and most democratic in the world."

Cleaver returned to the United States in 1975. Tried for his role in the 1968 shoot-out, Cleaver was found guilty of assault. The court was lenient and Cleaver, now a born-again Christian, received only five year's probation and directed to perform 2,000 hours of community service. David Hilliard, on the other hand, charged with the same offence, had received a one to ten year prison term.

After his trial he ran the Cleaver Crusade for Christ. Later, he came up with a plan for "Christlam," a plan to combine Christianity and Islam. He published Soul on Ice (1978) and for a time he advocated the religious ideas of Sun Myung Moon and became involved with Mormonism. During the 1980s he became a supporter of Ronald Reagan.

Cleaver, who for a time worked as a tree surgeon, divorced his wife, Kathleen Cleaver, in 1985. He continued to struggle with drug problems and in 1994 was seriously injured when he was knocked unconscious while buying cocaine from a drug dealer.

On his release from hospital he worked for the Black Chamber of Commerce in San Francisco . He also taught at a Bible college in Miami. However, in 1998 he was placed on probation in 1998 after convictions for burglary and cocaine possession.

Eldridge Cleaver died at Pomona Valley Medical Center on 1st May, 1998. His family requested that the hospital did not reveal the cause of his death.

Primary Sources

(1) Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (1968)

After I returned to prison (in 1958) I took a long look at myself and for the first time in my life admitted that I was wrong, and that I had gone astray - astray not so much from the white man's law as from being human, civilized. My pride as a man dissolved and my whole fragile structure seemed to collapse, completely shattered. That is why I started to write. To save myself.

(2) Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (1968)

You don't have to teach people to be human. You have to teach them how to stop being inhuman.

(3) Kathleen Neal Cleaver, Memories of Love and War (1999)

Waves of rebellion spread across black communities with the news of King's killing. Memphis, Birmingham, Chicago, Detroit, New York, and a score of other cities erupted that weekend. Washington, DC, went up in flames. In the Bay Area, police cars flooded black neighborhoods, and the National Guard was put on alert. Garry got the arrest warrant for Bobby Seale withdrawn, and they held a press conference at the courthouse on Friday. Bobby had shaved his mustache and beard to disguise himself, and his face took on a young, innocent look. Bobby emphasized that the Black Panther Party opposed rioting as both futile and self-destructive, for black neighborhoods were always the worst harmed. He spoke on radio, television, and at rallies in a marathon effort to staunch the disaster splattering around us. Eldridge told me that it was all the staff could do to explain how senseless it was to the hundreds of people who rushed to our office clamoring for guns to vent their rage in a disorganized manner.

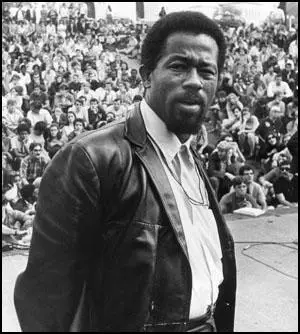

On Saturday, Eldridge and I met at the entrance to Sproul Plaza at Berkeley to go to the rally he was speaking at on campus. Standing on the sidewalk, I looked up at him, his black leather jacket gleaming in the sun. With his black turtleneck sweater, black pants, black boots, and black sunglasses, he seemed cloaked in death. I shuddered. The thought flashed through my mind that I would never see him again. I pushed it away - anything might happen - but I didn't want to think about it now. A wave of tenderness swept over me, as I thought of how casually Eldridge was risking his life to keep Huey out of the gas chamber.

Eldridge gave an electrifying speech. He didn't want to remain at the rally, but instead insisted on rushing back to the Panther office. "Isn't there someplace I can take you for a few hours?" he asked. "I don't want you at the office today, and I think it's too hot for you to go back home."

"Drop me off at Kay's house," I said. "I haven't seen her lately, and she lives near the campus."

Kay was a graduate student at Berkeley. She and I had been friends since we were children in Tuskegee, where her cousin Sammy Younge was murdered for his involvement in the civil rights movement. After he was shot, I had dropped out of college and joined the movement. That evening at her house, Kay and I talked about our lives until her husband, Bill, got home.

After dinner, we all watched the late news in the living room. Scenes of local memorial rallies for Dr. King and riots breaking out around the country dominated. Kay and Bill went to bed after the news was over, and I pulled the telephone over to the coffee table that faced the sofa, wondering why Eldridge was taking so long to come pick me up.

A bulletin flashed across the screen about a shoot-out involving the Oakland police - no location or time was mentioned. I recalled my earlier premonition about Eldridge's death, then blanked out there on the sofa, waiting for the phone to ring. I slept so soundly that none of the calls stirred me until around five the next morning. I answered the ringing telephone.

Alex Hoffman, one of Huey's attorneys, was saying in his low, tired voice, "I suppose you've heard by now, Kathleen, but Eldridge is in San Quentin."

Alex went on to say that Eldridge and seven other Panthers had been arrested last night after a shoot-out near David Hilliard's house, and that Bobby Hutton had been killed.

I went numb with shock.

"I'll take you to see Eldridge in prison as soon as I can get the details worked out," Alex said. "Always leave a number where I can reach you."

By the time I saw Alex on Sunday, Eldridge had been shuttled off to the prison in Vacaville, some fifty miles north of the Bay Area, isolating him from the rest of the jailed Panthers. Alex and I were waiting in a drab cubicle reserved for attorneys' visits when I spotted Eldridge being pushed down the hallway in a wheelchair. He looked like a captured giant, cuts and scratches on his face, the hair burned off the top of his head, his foot covered by a huge white bandage. When the guard wheeled him into the room, I could see that Eldridge's eyes were swollen, his face puffy, and his beard matted.

The sight left me too dazed to cry. Now I understood the glazed expression I'd seen in photographs of the faces of people whose homes or churches had been bombed, as if they couldn't believe what they were looking at. Anticipating or reading about terrifying violence does not prepare you to accept it. I felt too scared of what might happen to Eldridge in that notorious prison to dwell on how close he had come to being killed the night before.

Since I'd last seen him, he'd been trapped in an Oakland basement where he and Bobby Hutton had run for cover after gunshots flew between two Oakland police and several carloads of Black Panthers. A fifty-man assault force pounded bullets into the house where they hid for ninety minutes. When a tear-gas canister that had been thrown into the basement caught fire, Eldridge and Bobby agreed to surrender. Eldridge was not able to walk because a bullet had hit his leg. He told Bobby to take off his clothes so the police could not accuse him of hiding a weapon, but Bobby only removed his shirt. When he walked out into the floodlights in front of the house with his hands in the air, a hail of bullets killed him on the spot. Only the shouts from the crowd drawn by the gunfire saved Eldridge from an immediate death when he crawled out of the basement behind Bobby.

(4) CNN News, (1st May, 1998)

Eldridge Cleaver, the 1960s Black Panther activist and fugitive who later swung to the other side of the political spectrum to become a Republican, died Friday at the age of 62.

Cleaver died at 6:20 a.m. at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center in suburban Los Angeles. Citing a family request for privacy, hospital spokeswoman Leslie Porras declined to provide a cause of death or any details about his hospitalization.

At the time of his death, Cleaver was working as a university diversity consultant. Last month, he appeared at an Earth Day conference in Portland, Oregon. "I've gone beyond civil rights and human rights to creation rights," he said.

(5) Reginald Major, Soul on Ice Never Melted (7th Mat, 1998)

When I heard Eldridge Cleaver was dead, I realized for the first time why he put himself outside the orbit of people, like myself, who were once his friends and comrades.

It came to me that everything meaningful he had done since leaving prison and writing "Soul On Ice" - aside from marrying and starting a family - had been in support of the Black Panther Party. In the early days of the Party he and Huey P. Newton were nearly inseparable. When Huey went to prison, it was Cleaver who organized the "Free Huey" campaign and designed the coalition politics which got the white left to support it.

In 1975, Cleaver, then in exile in Algeria, split with Newton. The widely accepted explanation of the break - irreconcilable differences regarding revolutionary violence - is simplistic, irrelevant. They fell out because Cleaver believed the Party leaders in Oakland were living decadent lives, betraying the Panthers.

This breakup, I now realize, sent Cleaver into another form of exile - this time a spiritual exile. Talk about soul on ice! His essence went into deep freeze. Cleaver became his own opposite, banished himself into the ideological land of his former enemies.