Malcolm X

Malcolm Little, the son of an African American Baptist preacher, Earl Little, was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on 19th May, 1925. Malcolm's mother, Louise Little, was born in the West Indies. Her mother was black but her father was a white man.

Earl Little was a member of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and a supporter of Marcus Garvey. This got him into trouble with the Ku Klux Klan. Malcolm later recalled: "When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home in Omaha, Nebraska, one night. Surrounding the house, brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out. My mother went to the front door and opened it. Standing where they could see her pregnant condition, she told them that she was alone with her three small children, and that my father was away, preaching in Milwaukee." The Klansmen warned her that we had better get out of town because "the good Christian white people" were not going to stand for her husband "spreading trouble" among the "good" Negroes of Omaha with the "back to Africa" preachings of Marcus Garvey.

The family now moved to Lansing, Michigan. Little continued to make speeches in favour of UNIA and in 1929 the family house was attacked by members of the Black Legion, a militant group that had broken away from the Ku Klux Klan. "Shortly after my youngest sister was born came the nightmare night of 1929, my earliest vivid memory. I remember being suddenly snatched awake into a frightening confusion of pistol shots and shouting and smoke and flames. My father had shouted and shot at the two white men who had set the fire and were running away. Our home was burning down around us. We were lunging and bumping and tumbling all over each other trying to escape. My mother, with the baby in her arms, just made it into the yard before the house crashed in, showing sparks."

In 1931 Earl Little was found dead by a streetcar railway track. Although no one was convicted of the crime it was generally believed that Little had been murdered by the Black Legionnaires. Malcolm's mother never recovered from her husband's death and in 1937 was sent to the State Mental Hospital at Kalamazoo, where she stayed for the next twenty-six years.

Little moved to Boston to live with his sister. He worked as a waiter in Harlem and after becoming addicted to cocaine, turned to crime. In 1946 he was convicted of burglary and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. While in prison he was converted to the Black Muslim faith and the teachings of Elijah Muhammad: "The teachings of Mr. Muhammad stressed how history had been whitened - when white men had written history books, the black man simply had been left out. Mr. Muhammad couldn't have said anything that would have struck me much harder. I had never forgotten how when my class, me and all those whites, had studied seventh-grade United States history back in Mason, the history of the Negro had been covered in one paragraph. This is one reason why Mr. Muhammad teachings spread so swiftly all over the United States, among all Negroes, whether or not they became followers of Mr. Muhammad. The teachings ring true - to every Negro. You can hardly show me a black adult in America - or a white one, for that matter - who knows from the history books anything like the truth about the black man's role."

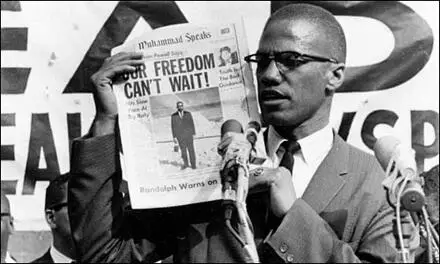

After his release from prison in 1952 he moved to Chicago where he met Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam sect. He changed his name to X, a custom among Muhammad's followers who considered their family names to have originated with white slaveholders. Malcolm soon became a leading figure in the movement. He went on several speaking tours and helped establish several new mosques. He was eventually assigned to be minister of the mosque in New York's Harlem area. Founder and editor of Muhammad Speaks, Malcolm rejected integration and racial equality and instead advocated black power.

Malcolm X began to advocate violent revolution. In a speech on 9th November, 1963: "Look at the American Revolution in 1776. That revolution was for what? For land. Why did they want land? Independence. How was it carried out? Bloodshed. Number one, it was based on land, the basis of independence. And the only way they could get it was bloodshed. The French Revolution - what was it based on? The landless against the landlord. What was it for? Land. How did they get it? Bloodshed. Was no love lost, was no compromise, was no negotiation. I'm telling you - you don't know what a revolution is. Because when you find out what it is, you'll get back in the alley, you'll get out of the way. The Russian Revolution - what was it based on? Land; the landless against the landlord. How did they bring it about? Bloodshed. You haven't got a revolution that doesn't involve bloodshed. And you're afraid to bleed. I said, you're afraid to bleed."

Malcolm was suspended from the movement by Elijah Muhammad after he made a series of extremist speeches. This included his comments that the assassination of John F. Kennedy was a "case of chickens coming home to roost".

In March 1964 Malcolm left the Nation of Islam and established his own religious organization, the Organization of Afro-American Unity. After a pilgrimage to Mecca, Malcolm rejected his former separatist beliefs and advocated world brotherhood. Malcolm now blamed racism on Western culture and urged African Americans to join with sympathetic whites to bring to an end.

Malcolm X argued: "The American black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own businesses, and decent homes for himself. As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, patronize their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race's ability to do for itself. That's the only way the American black man is ever going to get respect. One thing the white man never can give the black man is self-respect! The black man never can be become independent and recognized as a human being who is truly equal with other human beings until he has what they have, and until he is doing for himself what others are doing for themselves. The black man in the ghettoes, for instance, has to start self-correcting his own material, moral and spiritual defects and evils. The black man needs to start his own program to get rid of drunkenness, drug addiction, prostitution. The black man in America has to lift up his own sense of values."

On 12th February, 1965 Malcolm X visited Smethwick in Birmingham. Malcolm compared the treatment of ethnic minority residents with the treatment of Jews under Adolf Hitler, saying: "I would not wait for the fascist element in Smethwick to erect gas ovens."

In the 1964 General Election the Labour Party obtained a swing of 3% to obtain victory. However, some Conservative Party members played the race-card during the election. This included Peter Griffiths, who was taking on Patrick Gordon Walker, who had been Shadow Foreign Secretary, in Smethwick. The constituency had the highest percentage of recent immigrants to England and during the campaign his supporters used the slogan "If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour".

Griffiths himself did not coin the phrase or approve its use, but he refused to disown it. "I would not condemn any man who said that, I regard it as a manifestation of popular feeling". Griffiths reminded the electorate that Walker had opposed the introduction of the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act. “How easy to support uncontrolled immigration when one lives in a garden suburb,” Griffiths sneered at his Labour rival during the general election campaign. Griffiths won the seat with a 7.2 % swing to the Conservatives and reduced Walker's vote from 20,670 in the previous election to 14,916.

Malcolm X was shot dead at a party meeting in Harlem on 21st February, 1965. Three Black Muslims were later convicted of the murder. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, based on interviews he had given to the journalist, Alex Haley, was published in 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) Malcolm X, Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

My father was a big, six-foot-four, very black man. He had only one eye. How he lost the other one I have never known. He was from Reynolds, Georgia, where he had left school after the third or maybe fourth grade. He believed, as did Marcus Garvey, that freedom, independence and self-respect could never be achieved by the Negro in America, and that therefore the Negro should leave America to the white man and return to his African land of origin.

Louise Little, my mother, who was born in Grenada, in the British West Indies, looked like a white woman. Her father was white. She had straight black hair, and her accent did not sound like a Negro's. Of this white father of hers, I know nothing except her shame about it. I remember hearing her say she was glad that she had never seen him. It was, of course, because of him that I got my reddish-brown color of skin, and my hair of the same color.

(2) Malcolm X, Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home in Omaha, Nebraska, one night. Surrounding the house, brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out. My mother went to the front door and opened it. Standing where they could see her pregnant condition, she told them that she was alone with her three small children, and that my father was away, preaching in Milwaukee. The Klansmen shouted threats and warnings at her that we had better get out of town because "the good Christian white people" were not going to stand for my father's "spreading trouble" among the "good" Negroes of Omaha with the "back to Africa" preachings of Marcus Garvey.

(3) After his family were threatened by the Ku Klux Klan in Omaha, Earl Little moved his family to Lansing, Michigan.

My father bought a house and soon, as had been his pattern, he was doing free-lance Christian preaching in local Negro Baptist churches, and during the week he was roaming about spreading word of Marcus Garvey.

This time, "the get out of town" came from a local hate society called The Black Legion. They wore black robes instead of white. Soon, nearly everywhere my father went, Black Legionnaires were reviling him as an "uppity n*****" for wanting to own a store, for living outside the Lansing Negro district for spreading unrest and dissension among "the good n*****".

Shortly after my youngest sister was born came the nightmare night of 1929, my earliest vivid memory. I remember being suddenly snatched awake into a frightening confusion of pistol shots and shouting and smoke and flames. My father had shouted and shot at the two white men who had set the fire and were running away. Our home was burning down around us. We were lunging and bumping and tumbling all over each other trying to escape. My mother, with the baby in her arms, just made it into the yard before the house crashed in, showing sparks.

(4) In 1940 Malcolm Little moved to Boston where he attended the high school in Roxbury. He later recalled a conversation with his English teacher.

I happened to be alone in the classroom with Mr. Ostrowski, my English teacher. He was a tall, rather reddish white man and he had a thick mustache. I had gotten some of my best marks under him, and he had always made me feel that he liked me. I know that he probably meant well in what he happened to advise me that day. I doubt that he meant any harm. It was just in his nature as an American white man.

He told me, "Malcolm, you ought to be thinking about a career. Have you been giving it thought?" The truth is, I hadn't. I had never figured out why I told him, "Well, yes, sir, I've been thinking I'd like to be a lawyer."

Mr. Ostrowski looked surprised, I remember, and leaned back in his chair and clasped his hands behind his head. He kind of half-smiled and said, "Malcolm, one of life's first needs is for us to be realistic. Don't misunderstand me, now. We all here like you, you know that. But you've got to be realistic about being a n*****. A lawyer - that's no realistic goal for a n*****. You need to think about something you can be. You're good with your hands - making things. Everybody admires your carpentry shop work. Why don't you plan on carpentry? People like you as a person - you'd get all kind of work."

(5) Malcolm X, Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

The teachings of Mr. Muhammad stressed how history had been "whitened" - when white men had written history books, the black man simply had been left out. Mr. Muhammad couldn't have said anything that would have struck me much harder. I had never forgotten how when my class, me and all those whites, had studied seventh-grade United States history back in Mason, the history of the Negro had been covered in one paragraph.

This is one reason why Mr. Muhammad teachings spread so swiftly all over the United States, among all Negroes, whether or not they became followers of Mr. Muhammad. The teachings ring true - to every Negro. You can hardly show me a black adult in America - or a white one, for that matter - who knows from the history books anything like the truth about the black man's role. In my own case, once I heard of the "glorious history of the black man", I took special pains to hunt in the library for books that would inform me on details about black history.

(6) Malcolm X, Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

Every month, I went to Chicago, I would find that some sister had written complaining to Mr. Muhammad that I talked so hard against women when I taught our special classes about the different natures of the two sexes. Now, Islam has very strict laws and teachings about women, the core of them being that the true nature of a man is to be strong, and a woman's true nature is to be weak, and while a man must at all times respect his woman, at the same time he needs to understand that he must control her if he expects to get her respect.

(7) Malcolm X, speech (9th November, 1963)

Look at the American Revolution in 1776. That revolution was for what? For land. Why did they want land? Independence. How was it carried out? Bloodshed. Number one, it was based on land, the basis of independence. And the only way they could get it was bloodshed. The French Revolution - what was it based on? The landless against the landlord. What was it for? Land. How did they get it? Bloodshed. Was no love lost, was no compromise, was no negotiation. I'm telling you - you don't know what a revolution is. Because when you find out what it is, you'll get back in the alley, you'll get out of the way.

The Russian Revolution - what was it based on? Land; the landless against the landlord. How did they bring it about? Bloodshed. You haven't got a revolution that doesn't involve bloodshed. And you're afraid to bleed. I said, you're afraid to bleed.

As long as the white man sent you to Korea, you bled. He sent you to Germany, you bled. He sent you to the South Pacific to fight the Japanese, you bled. You bleed for white people, but when it comes to seeing your own churches being bombed and little black girls murdered, you haven't got any blood. You bleed when the white man says bleed; you bite when the white man says bite; and you bark when the white man says bark. I hate to say this about us, but it's true. How are you going to be nonviolent in Mississippi, as violent as you were in Korea? How can you justify being nonviolent in Mississippi and Alabama, when your churches are being bombed, and your little girls are being murdered, and at the same time you are going to get violent with Hitler, and Tojo, and somebody else you don't even know?

If violence is wrong in America, violence is wrong abroad. If it is wrong to be violent defending black 'women and black children and black babies and black men, then it is wrong for America to draft us and make us violent abroad in defense of her. And if it is right for America to draft us, and teach us how to be violent in defense of her, then it is right for you and me to do whatever is necessary to defend our own people right here in this country.

So I cite these various revolutions, brothers and sisters, to show you that you don't have a peaceful revolution. You don't have a turn-the-other-cheek revolution. There's no such thing as a nonviolent revolution. The only kind of revolution that is nonviolent is the Negro revolution. The only revolution in which the goal is loving your enemy is the Negro revolution. It's the only revolution in which the goal is a desegregated lunch counter, a desegregated theater, a desegregated park, and a desegregated public toilet; you can sit down next to white folks - on the toilet. That's no revolution. Revolution is based on land. Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.

(8) Malcolm X, Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965)

The American black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own businesses, and decent homes for himself. As other ethnic groups have done, let the black people, wherever possible, patronize their own kind, and start in those ways to build up the black race's ability to do for itself. That's the only way the American black man is ever going to get respect. One thing the white man never can give the black man is self-respect! The black man never can be become independent and recognized as a human being who is truly equal with other human beings until he has what they have, and until he is doing for himself what others are doing for themselves.

The black man in the ghettoes, for instance, has to start self-correcting his own material, moral and spiritual defects and evils. The black man needs to start his own program to get rid of drunkenness, drug addiction, prostitution. The black man in America has to lift up his own sense of values.

I'm right with the Southern white man who believes that you can't have so-called "intergration", at least not for long, without intermarriage increasing. And what good is this for anyone?

(9) On his return from Mecca, Malcolm X explained his new views on racism and violence (March, 1964)

I don't speak against the sincere, well-meaning, good white people. I have learned that there are some. I have learned that not all white people are racists. I am speaking against and my fight is against the white racists. I believe that Negroes have the right to fight against these racists, by any means that are necessary.

I am for violence if non-violence means we continue postponing a solution to the American black man's problem - just to avoid violence. I don't go for non-violence if it also means a delayed solution. To me a delayed solution is a non-solution. Or I'll say it another way. If it must take violence to get the black man his human rights in this country, I'm for violence exactly as you know the Irish, the Poles, or Jews would be if they were flagrantly discriminated against.

(10) In her autobiography, Song in a Weary Throat, Pauli Murray wrote about her reactions to the assassination of Martin Luther King.

By strange coincidence, when the shattering news of Dr. King's slaying came over the radio in the evening of April, 1968, I happened to be reading the final chapters of The Autobiography of Malcolm X and had just finished a passage written shortly before Malcolm's own assassination in 1965. Malcolm had observed: "And in the racial climate in this country today, it is anybody's guess which of the 'extremes' in approach to the black man's problems might personally meet a fatal catastrophe first - 'non-violent' Dr. King, or so-called 'violent' me."

The prophetic power of Malcolm X's reflection was staggering. I had not been a passionate admirer of Dr. King himself because I felt he had not recognized the role of women in the civil rights movement (Rosa Parks was not even invited to join Dr. King's party when he went abroad to receive the Nobel Peace Prize), but I was passionately devoted to his cause. Beneath the numbness I felt after that fatal evening was the realization that the foremost advocate of nonviolence as a way of life - my own cause - was stilled and those who had embraced Dr. King's religious commitment to nonviolence were called upon to keep his tradition alive and to advance the work for which he gave his life.

(11) William Kunstler, interviewed by Dennis Bernstein in 1995.

Dennis Bernstein: What was your sense of the difference between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King?

William Kunstler: Well, I thought Malcolm was a more important figure, because he was sort of the cutting edge. I met him a week before he was killed, at LaGuardia airport. I was with a guy named Mike Felwell who had been with the fight for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party many years earlier, and he told us that he had had a conversation with Dr. King, and that they were going to meet in the future and sort of amalgamate. Malcolm would do the North, because Martin had failed miserably in Cicero; Martin would do the South. They thought they would open up the black movement to a much wider group of people. That very night his house was bombed in East Elmhurst, Queens, and then a week and a day later he was shot to death at the Audubon Ballroom. I thought that maybe this agreement, or putative agreement, had a lot to do with his assassination.