Bernard Pares

Bernard Pares, the third son and seventh child of John Pares, was born at Albury, Surrey, on 1st March 1867. His father was extremely wealthy and Bernard was educated at Harrow before winning a scholarship to Trinity College, where he read classics. After graduating from Cambridge University he worked as a schoolteacher but after receiving a sizeable inheritance he spent his time travelling around the world.

According to his biographer, Jonathan Haslam: "His first visit to Russia was undertaken in 1898, after studying on his private income in France, Italy, and Germany, apparently in rapt pursuit of Napoleon's fields of battle. Finally his interest was sparked by the exotic that Russia represented in contrast to Britain; the challenge presented itself of reconciling two societies that had, for the better part of the previous century, found themselves in contention."

After marriage on 27th August 1901 to Margaret Ellis, daughter of Edward Austin Dixon, dental surgeon, of Colchester, Pares became a university extension lecturer at Cambridge University. Over the next few years Margaret gave birth to five children, Peter, Andrew, Richard, Elizabeth and Susan. In 1906 he accepted a post teaching Russian history at Liverpool University where he became a popular lecturer.

Pares thought that the authorities mishandled the protests led by Father Georgi Gapon. "Gapon's organization was based on a representation of one person for every thousand workers. He planned a peaceful demonstration in the form of a march to the Winter Palace, carrying church banners and singing religious and national songs. Owing to the idiocy of the military authorities, the crowd was met with rifle fire both at the outskirts of the city and the palace square. The actual victims, as certified by a public commission of lawyers of the Opposition, was approximately 150 killed and 200 wounded; and as all who had taken a leading part in the procession were then expelled from the capital, the news was circulated all over the Empire."

Pares became excited by the formation of the first Russian parliament, the Duma, in 1906. Pares visited St. Petersburg, and after making contact with liberal representatives, became convinced that the constitutional experiment would succeed. This was reflected in his book, Russia and Reform (1907). However, his critics claimed that the book completely "neglected the economic and social undercurrents" in Russia. To support the reform movement, Pares became secretary for the Anglo-Russian Committee in London, which arranged parliamentary exchanges between the two capitals.

Pares became close to Alexander Guchkov: "He had the easy organizing ability of a first-rate English politician; he was quietly proud of his democratic origin, and all his actions were inspired by an ardent love for Russia and the Russian people, in whose native conservatism, common sense and loyalty he fully shared... Guchkov's chief quality was a daring gallantry; he was at ease with himself and enjoyed stepping forward under fire with a perfect calm whenever there was anything which he wished to challenge; his defect was his restlessness; without actually asking for it, he was instinctively always in the limelight, always trying to do too much."

Pares was highly critical of Tsar Nicholas II in his treatment of Jews: "At this time the favourite object of persecution was the Jewry of Russia, which was in 1914 nearly one half of the whole Jewish population of the world. And here Nicholas was as bad as Alexander. It was not just a question of what rights the Jews did not possess, but whether they had the right to exist at all. But for special exemptions, the Jewish population was confined to the so-called Jewish Pale of Settlement, where they lived under Polish rule before the partitions of Poland."

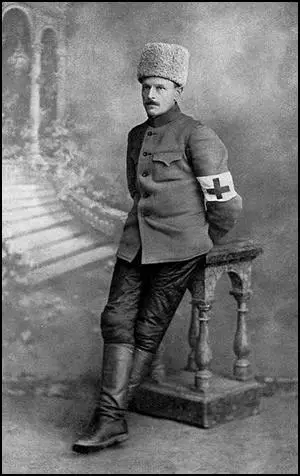

On the outbreak of the First World War Pares was appointed British Military Observer to the Russian Army. He thought the Tsar made a serious mistake by appointing Boris Sturmer as prime minister: "Sturmer was a shallow and dishonest creature, without even the merit of courage. Sturmer was prepared to pose as a semi-liberal and to try in this way to keep the Duma quiet. Rasputin backed Sturmer, and also the Empress, and he was suddenly appointed Prime Minister on February 2nd and to the surprise of everyone, and most of all Goremykin, who, as was usual with the Emperor, had never been given the idea that he was even in danger." In 1915 he published, Day by Day with the Russian Army.

The British government had established the secret War Propaganda Bureau on the outbreak of the First World War. Based on an idea put forward by David Lloyd George, the plan was to promoting Britain's interests during the war. This involved recruiting Britain's leading writers to write pamphlets that supported the war effort. Writers recruited included Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

One of the first pamphlets to be published was Report on Alleged German Outrages, that appeared at the beginning of 1915. This pamphlet attempted to give credence to the idea that the German Army had systematically tortured Belgian civilians. The great Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemakers, was recruited to provide the highly emotionally drawings that appeared in the pamphlet.

Bernard Pares became aware of the activities of the secret War Propaganda Bureau and suggested to Robert Bruce Lockhart, the British consul-general that a similar organization should be set up in Russia to control reporting on the Eastern Front. Lockhart set up a meeting with British journalists, including Arthur Ransome, in January 1916. After talking to Harold Williams, Lockhart submitted a proposal to the British ambassador Sir George Buchanan. The project was approved and became known as the International News Agency (Anglo-Russian Bureau). Funded by the Foreign Office and headed by Hugh Walpole, it placed pro-British stories in Russian newspapers. As well as Ransome, Pares and Williams, other members included Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily News and Morgan Philips Price of the Manchester Guardian.

After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Prince Lvov had always held aloof from a purely political life. He belonged to no party, and as head of the Government could rise above party issues. Not till later did the four months of his premiership demonstrate the consequences of such aloofness even from that very narrow sphere of political life which in Tsarist Russia was limited to work in the Duma and party activity. Neither a clear, definite, manly programme, nor the ability for firmly and persistently realising certain political problems were to be found in Prince G. Lvov. But these weak points of his character were generally unknown."

On 8th July, 1917, Alexander Kerensky became the new leader of the Provisional Government. In the Duma he had been leader of the moderate socialists and had been seen as the champion of the working-class. Bernard Pares was doubtful that Kerensky would be successful. He later wrote: "‘It was the most absurd time, for a country inexperienced in liberty, to make its first attempt at democratic government while the world war was still in progress, that is, while the world was ruled by force".

Harold Williams, believed that the Kornilov Revolt dramatically changed the situation and dramatically increased the influence of the Bolsheviks: "The Kornilov Affair has intensified mutual distrust and completed the work of destruction. The Government is shadowy and unreal, and what personality it had has disappeared before the menace of the Democratic Assembly. Whatever power there is again concentrated in the hands of the Soviets, and, as always happens when the Soviets secure a monopoly of power, the influence of the Bolsheviks has increased enormously. Kerensky has returned from Headquarters, but his prestige has declined, and he is not actively supported either by the right or by the left."

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Vladimir Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Felix Dzerzhinsky (Internal Affairs), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice) and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War).

Elections for the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917. The election was won by the Socialist Revolutionaries. The Bolsheviks were bitterly disappointed with the result as they hoped it would legitimize the October Revolution. When it opened on 5th January, 1918, Victor Chernov, leader of the SRs, was elected President. When the Assembly refused to support the programme of the new Soviet Government, the Bolsheviks walked out in protest. Later that day, Lenin announced that the Constituent Assembly had been dissolved. Soon afterwards all opposition political groups were banned in Russia.

Bernard Pares now left Russia. The British Foreign Office asked him to go to Siberia where he joined up with Admiral Alexander Kolchak. Pares's biographer, Jonathan Haslam has argued: "Pares went to Siberia, which was dominated by the less-than-liberal Admiral Kolchak, whom the British were backing blindly in a fruitless war against the Bolsheviks. Here Pares entertained the counter-revolutionary forces to lectures twice a week on the duty of Russia to others and the duty of others to Russia. As Hodgson recalled, even though the former was less popular than the latter, Pares none the less held his audience." After the defeat of the White Army Pares returned to Britain.

In 1919 he was appointed KBE for his service in Russia, and held the key chair in Russian language, literature, and history at London University. Pares also become editor of the Slavonic Review and simultaneously director of the fledgeling School of Slavonic and East European Studies at King's College. Books by Pares included A History of Russia (1926), Fall of the Russian Monarchy (1939), Russia and the Peace (1944) and the autobiographical work, A Wandering Student (1948).

Bernard Pares died on 17th April 1949 in New York City.

Primary Sources

(1) Bernard Pares was a regular visitor to Russia during the reign of Nicholas II.

At this time the favourite object of persecution was the Jewry of Russia, which was in 1914 nearly one half of the whole Jewish population of the world. And here Nicholas was as bad as Alexander. It was not just a question of what rights the Jews did not possess, but whether they had the right to exist at all. But for special exemptions, the Jewish population was confined to the so-called Jewish Pale of Settlement, where they lived under Polish rule before the partitions of Poland.

(2) Bernard Pares wrote about George Gapon and Bloody Sunday in his book the The Fall of the Russian Monarchy (1939)

Gapon's organization was based on a representation of one person for every thousand workers. He planned a peaceful demonstration in the form of a march to the Winter Palace, carrying church banners and singing religious and national songs. Owing to the idiocy of the military authorities, the crowd was met with rifle fire both at the outskirts of the city and the palace square. The actual victims, as certified by a public commission of lawyers of the Opposition, was approximately 150 killed and 200 wounded; and as all who had taken a leading part in the procession were then expelled from the capital, the news was circulated all over the Empire.

(3) Bernard Pares wrote about Sergei Sazonov in his book, The Fall of the Russian Monarchy (1939).

At this time the Tsar nor his army had any doubt (that if there was a war) of the ultimate victory of the Triple Entente, and Nicholas played at the then fashionable game of redividing up the world. Russia must receive Posen, part of Silesia, Galicia and North Bukovina which will permit her to reach her natural limit, the Carpathians. The Turks were to be driven from Europe; the Northern Straits might be Bulgarian, but the environs of Constantinople - Sazonov had not yet asked for the city itself - must be in the hands of Russia.

(4) Bernard Pares met Alexander Guchkov several times between 1898 and 1917.

Guchkov, grandson of a serf, son of a merchant and magistrate of Moscow, was a restless spirit always coming into prominence on this or that issue of the moment. Guchkov's chief quality was a daring gallantry; he was at ease with himself and enjoyed stepping forward under fire with a perfect calm whenever there was anything which he wished to challenge; his defect was his restlessness; without actually asking for it, he was instinctively always in the limelight, always trying to do too much.

He had the easy organizing ability of a first-rate English politician; he was quietly proud of his democratic origin, and all his actions were inspired by an ardent love for Russia and the Russian people, in whose native conservatism, common sense and loyalty he fully shared.

(5) Bernard Pares wrote about Alexander Protopopov, Michael Rodzianko and Gregory Rasputin in his book, The Fall of the Russian Monarchy (1939).

Protopopov was elected to the Duma, and was actually chosen as Vice-President; there he posed as a moderate liberal asking for an extension of parliamentary rights.

Suffering from ill health, which was later to develop into progressive paralysis, he sought the attentions of Rasputin, who put him through a prolonged cure.

Rodzianko, who was a poor judge of men, took account of him; so also did Guchkov, who regarded him as a man who could get things done. In the Duma, as elsewhere, Protopopov played for popularity, and was this to be considered as a member of the Progressives. Protopopov was in reality not Rodzianko's man, but Rasputin's.

(6) Bernard Pares believed that Nicholas II made a serious mistake when he appointed Boris Sturmer as Prime Minister during the First World War.

Sturmer was a shallow and dishonest creature, without even the merit of courage. Sturmer was prepared to pose as a semi-liberal and to try in this way to keep the Duma quiet. Rasputin backed Sturmer, and also the Empress, and he was suddenly appointed Prime Minister on February 2nd and to the surprise of everyone, and most of all Goremykin, who, as was usual with the Emperor, had never been given the idea that he was even in danger.