On this day on 6th January

On this day in 1367 Richard, the second son of Edward, the Black Prince and Joan of Kent, was born. His elder brother, Edward of Angoulême, died in 1371 and Richard stood in the direct line of succession to the English throne, and the prospect of his succeeding while he was still a child was brought appreciably nearer by the deepening illness of his father, who died on 8th April 1376. Parliament feared that Richard's uncle, John of Gaunt, would usurp the throne and for this reason, he was quickly invested with the princedom of Wales and his father's other titles.

Richard's grandfather, King Edward III, was having serious problems with what became known as the Hundred Years War. Fighting the war was very expensive and in February 1377 the government introduced a poll-tax where four pence was to be taken from every man and woman over the age of fourteen. "This was a huge shock: taxation had never before been universal, and four pence was the equivalent of three days' labour to simple farmhands at the rates set in the Statute of Labourers".

King Edward died soon afterwards. Richard, his ten-year-old grandson, was crowned in July 1377. Thomas Walsingham described it as "a day of joy and gladness.... the long-awaited day of the renewal of peace and of the laws of the land, long exiled by the weakness of an aged king and the greed of his courtiers and servants."

Richard's main advisers were his uncle, John of Gaunt and his younger brother Thomas of Woodstock. Other important figures included Simon de Burley and Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland. However, the appointment of a regency council was chosen so no one person could gain permanent control of policy.

John of Gaunt was closely associated with the new poll-tax and this made him very unpopular with the people. They were very angry as they considered the tax unfair as the poor had to pay the same tax as the wealthy. Despite this, the collectors of the tax seem not to have had to face more than an occasional, local disturbance.

In 1379 Richard II called a parliament to raise money to pay for the continuing war against the French. After much debate it was decided to impose another poll tax. This time it was to be a graduated tax, which meant that the richer you were, the more tax you paid. For example, the Duke of Lancaster and the Archbishop of Canterbury had to pay £6.13s.4d., the Bishop of London, 80 shillings, wealthy merchants, 20 shillings, but peasants were only charged 4d.

The proceeds of this tax was quickly spent on the war or absorbed by corruption. In 1380, Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury, suggested a new poll tax of three groats (one shilling) per head over the age of fifteen. "There was a maximum payment of twenty shillings from men whose families and households numbered more than twenty, thus ensuring that the rich paid less than the poor. A shilling was a considerable sum for a working man, almost a week's wages. A family might include old persons past work and other dependents, and the head of the family became liable for one shilling on each of their 'polls'. This was basically a tax on the labouring classes."

The peasants felt it was unfair that they should pay the same as the rich. They also did not feel that the tax was offering them any benefits. For example, the English government seemed to be unable to protect people living on the south coast from French raiders. Most peasants at this time only had an income of about one groat per week. This was especially a problem for large families. For many, the only way they could pay the tax was by selling their possessions. John Wycliffe gave a sermon where he argued: "Lords do wrong to poor men by unreasonable taxes... and they perish from hunger and thirst and cold, and their children also. And in this manner the lords eat and drink poor men's flesh and blood."

John Ball toured Kent giving sermons attacking the poll tax. When the Archbishop of Canterbury, heard about this he gave orders that Ball should not be allowed to preach in church. Ball responded by giving talks on village greens. The Archbishop now gave instructions that all people found listening to Ball's sermons should be punished. When this failed to work, Ball was arrested and in April 1381 he was sent to Maidstone Prison. At his trial it was claimed that Ball told the court he would be "released by twenty thousand armed men".

In May 1381, Thomas Bampton, the Tax Commissioner for the Essex area, reported to the king that the people of Fobbing were refusing to pay their poll tax. It was decided to send a Chief Justice and a few soldiers to the village. It was thought that if a few of the ringleaders were executed the rest of the village would be frightened into paying the tax. However, when Chief Justice Sir Robert Belknap arrived, he was attacked by the villagers.

Belknap was forced to sign a document promising not to take any further part in the collection of the poll tax. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's: "The Commons rose against him and came before him to tell him... he was maliciously proposing to undo them... Accordingly they made him swear on the Bible that never again would he hold such sessions nor act as Justice in such inquests... And Sir Robert travelled home as quickly as possible."

After releasing the Chief Justice, some of the villagers looted and set fire to the home of John Sewale, the Sheriff of Essex. Tax collectors were executed and their heads were put on poles and paraded around the neighbouring villages. The people responsible sent out messages to the villages of Essex and Kent asking for their support in the fight against the poll tax.

Many peasants decided that it was time to support the ideas proposed by John Ball and his followers. It was not long before Wat Tyler, a former soldier in the Hundred Years War, emerged as the leader of the peasants. Tyler's first decision was to march to Maidstone to free John Ball from prison. "John Ball had been set free and was safe among the commons of Kent, and he was bursting to pour out the passionate words which had been bottled up for three months, words which were exactly what his audience wanted to hear."

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) has pointed out that it was very important for the peasants to be led by a religious figure: "For some twenty years he had wandered the country as a kind of Christian agitator, denouncing the rich and their exploitation of the poor, calling for social justice and freeman and a society based on fraternity and the equality of all people." John Ball was needed as their leader because alone of the rebels, he had access to the word of God. "John Ball quickly assumed his place as the theoretician of the rising and its spiritual father. Whatever the masses thought of the temporal Church, they all considered themselves to be good Catholics."

On 5th June there was a revolt at Dartford and two days later Rochester Castle was taken. The peasants arrived in Canterbury on 10th June. Here they took over the archbishop's palace, destroyed legal documents and released prisoners from the town's prison. More and more peasants decided to take action. Manor houses were broken into and documents were destroyed. These records included the villeins' names, the rent they paid and the services they carried out. What had originally started as a protest against the poll tax now became an attempt to destroy the feudal system.

The peasants decided to go to London to see Richard II. As the king was only fourteen-years-old, they blamed his advisers for the poll tax. The peasants hoped that once the king knew about their problems, he would do something to solve them. The rebels reached the outskirts of the city on 12 June. It has been estimated that approximately 30,000 peasants had marched to London. At Blackheath, John Ball gave one of his famous sermons on the need for "freedom and equality".

Wat Tyler also spoke to the rebels. He told them: "Remember, we come not as thieves and robbers. We come seeking social justice." Henry Knighton records: "The rebels returned to the New Temple which belonged to the prior of Clerkenwell... and tore up with their axes all the church books, charters and records discovered in the chests and burnt them... One of the criminals chose a fine piece of silver and hid it in his lap; when his fellows saw him carrying it, they threw him, together with his prize, into the fire, saying they were lovers of truth and justice, not robbers and thieves."

Charles Poulsen praises Wat Tyler as learning the "lessons of organisation and discipline" when in the army and in showing the "same pride in the customs and manners of his own class as the noblest baron would for his". (19) The medieval historians were less complimentary and Thomas Walsingham described him as a "cunning man, endowed with much sense if he had applied his intelligence to good purposes".

Richard II gave orders for the peasants to be locked out of London. However, some Londoners who sympathised with the peasants arranged for the city gates to be left open. Jean Froissart claims that some 40,000 to 50,000 citizens, about half of the city's inhabitants, were ready to welcome the "True Commons". When the rebels entered the city, the king and his advisers withdrew to the Tower of London. Many poor people living in London decided to join the rebellion. Together they began to destroy the property of the king's senior officials. They also freed the inmates of Marshalsea Prison.

Part of the English Army was at sea bound for Portugal whereas the rest were with John of Gaunt in Scotland. Thomas Walsingham tells us that the king was being protected in the Tower by "six hundred warlike men instructed in arms, brave men, and most experienced, and six hundred archers". Walsingham adds that they "all had so lost heart that you would have thought them more like dead men than living; the memory of their former vigour and glory was extinguished". Walsingham points out that they did not want to fight and suggests they may have been on the side of the peasants.

John Ball sent a message to Richard II stating that the rising was not against his authority as the people only wished only to deliver him and his kingdom from traitors. Ball also asked the king to meet with him at Blackheath. Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales, the treasurer, both objects of the people's hatred, warned against meeting the "shoeless ruffians", whereas others, such as William de Montagu, the Earl of Salisbury, urged that the king played for time by pretending that he desired a negotiated agreement.

Richard II's biographer, Anthony Tuck, has pointed out: "Richard's own part in the discussions is almost impossible to determine, though some historians have suggested that he took the initiative in seeking to negotiate with the rebels, despite the fact that he was only fourteen when the rebellion occurred. Even before the Kentish rebels entered London, Richard had apparently suggested negotiation with their leaders at Greenwich, but the talks had broken down almost as soon as they began."

Richard II agreed to meet the rebels outside the town walls at Mile End on 14th June, 1381. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End".

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract".

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London.

While the king was in Mile End discussing an agreement with the king, another group of peasants marched to the Tower of London. There were about 600 soldiers defending the Tower but they decided not to fight the rebel army. Simon Sudbury (Archbishop of Canterbury), Robert Hales (King's Treasurer) and John Legge (Tax Commissioner), were taken from the Tower and executed. Their heads were then placed on poles and paraded through the streets of cheering Londoners.

Rodney Hilton argues that the rebels wanted revenge on all those involved in the levying of taxes or the administrating the legal system. Roger Leggett, one of the most important government lawyers was also killed. "They attacked not only the lawyers themselves - attorneys, pleaders, clerks of the courts - but others closely associated with the judicial processes... The hostility to lawyers and to legal records was not of course peculiar to the Londoners. The widespread destruction of manorial court records is well-known" during the rebellion.

The rebels also attacked foreign workers living in London. "The commons made proclamation that every one who could lay hands on Flemings or any other strangers of other nations might cut off their heads". It has been claimed that "some 150 or 160 unhappy foreigners were murdered in various places - thirty-five Flemings in one batch were dragged out of the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and beheaded on the same block... The Lombards also suffered, and their houses yielded much valuable plunder."

It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins.

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded."

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages.

Chroniclers such as Henry Knighton and Thomas Walsingham suggested that these events were unplanned and unexpected. However, modern historians have doubts about this version of events. Anthony Tuck has argued: "The rapid arrival of the militia suggests some element of advance planning, and those around the king, even perhaps the king himself, may have intended to create an opportunity to kill or capture Tyler and separate him from the main body of his followers. If this is so, it was a risky strategy, as the Mile End meeting had been, and again Richard's personal courage is not in doubt."

An army, led by Thomas of Woodstock, John of Gaunt's younger brother, was sent into Essex to crush the rebels. A battle between the peasants and the King's army took place near the village of Billericay on 28th June. The king's army was experienced and well-armed and the peasants were easily defeated. It is believed that over 500 peasants were killed during the battle. The remaining rebels fled to Colchester, where they tried in vain to persuade the towns-people to support them. They then fled to Huntingdon but the towns people there chased them off to Ramsey Abbey where twenty-five were slain.

King Richard with a large army began visiting the villages that had taken part in the Peasants' Revolt. At each village, the people were told that no harm would come to them if they named the people in the village who had encouraged them to join the rebellion. Those people named as ringleaders were then executed. Apparently the king stated: "Serfs you are and serfs you will remain." A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has pointed out: "The promises made by the king were repudiated and the common people of England learnt, not for the last time, how unwise it was to trust to the good faith of their rulers."

The king's officials were instructed to look out for John Ball. He was eventually caught in Coventry. He was taken to St Albans to stand trial. "He denied nothing, he freely admitted all the charges without regrets or apologies. He was proud to stand before them and testify to his revolutionary faith." He was sentenced to death, but William Courtenay, the Bishop of London, granted a two-day stay of execution in the hope that he could persuade Ball to repent of his treason and so save his soul. John Ball refused and he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 15th July, 1381.

In 1382 John Wycliffe was condemned as a heretic and was forced into retirement. Archbishop William Courtenay urged Parliament to pass a Statute of the Realm against preachers such as Wycliffe: "It is openly known that there are many evil persons within the realm, going from county to county, and from town to town, in certain habits, under dissimulation of great holiness, and without the licence ... or other sufficient authority, preaching daily not only in churches and churchyards, but also in markets, fairs, and other open places, where a great congregation of people is, many sermons, containing heresies and notorious errors."

Although initially it failed to achieve its aim, the Peasants' Revolt was an important event in English history. For the first time, peasants had joined together in order to achieve political change. The king and his advisers could no longer afford to ignore their feelings. In 1382 a new poll tax was voted in by Parliament. This time it was decided that only the richer members of society should pay the tax.

After the Peasants Revolt the lords found it very difficult to retain the feudal system. Villeinage was already crumbling due to economic and demographic pressures. Labour was still in short supply and villeins continued to run away to find work as freemen. In 1390 the government attempt to keep wages at the old level was abandoned when a new Statute of Labourers Act gave the Justices of the Peace the power to fix wages for their districts in accordance with the prevailing prices.

Even the villeins who stayed were much more reluctant to work on the lord's demesne. In some villages the villeins joined together and refused to carry out any more labour services. Several towns and villages saw outbreaks of violence. However, as Charles Oman has pointed out, these were "scattered and sporadic, instead of simultaneous".

As an economic means of cultivating the soil for profit, villeinage was doomed. "With such surly and mutinous labour and no police to enforce it, it proved impossible to make it pay." Unable to find enough labour to work their demesne, lords found it more profitable to lease out the land. With smaller areas to farm, the lords had less need for the labour services provided by the villeins. Lords started to "commute" these labour services. This meant that in return for a cash payment, peasants no longer had to work on the lord's demesne. During this period wages increased significantly.

Richard married 16-year-old Anne of Bohemia on 20th January 1382. She was the daughter of the late Emperor Charles IV. Anne's father had been the most powerful monarch in Europe at the time, ruling over about half of Europe's population and territory. The marriage was against the wishes of many members of his nobility and members of parliament, and occurred primarily at the instigation of Richard close associate, Michael de la Pole, 1st Earl of Suffolk. "She did not produce an heir (there are no reports of stillborn children, or children who died in infancy: in all probability she never became pregnant), but no chronicler reports any other liaisons on the king's part."

At the time of his marriage he was described as being "fair-haired and self-consciously youthful, keeping his face clean-shaven when it was conventional for grown men to wear a beard". A contemporary said he was "abrupt and somewhat stammering in his speech, capricious in his manners... prodigal in his gifts, extravagantly splendid in his entertainments and dress."

According to Henry Knighton, Queen Anne requested that Richard should forgive the rebels: "In the following year, 1382, at the special request of Queen Anne and other magnates of the realm, especially the pious Duke of Lancaster, the lord King gave a general pardon to all the aforesaid rebels and malefactors, their adherents, abettors and followers. He granted charters to this effect and through God's mercy the previous madness came to an end."

Richard was very interested in fashion and pioneered the codpiece, worn over tight hose, embroidered doublets with padded shoulders and the houpelande (a long coloured robe with a high neck that replaced the more traditional cloak). "Such fashions were designed to display the male physique to perfection, emphasising long legs, a slim waist and powerful shoulders."

Richard II was not a very successful military commander. His biographer, Peter Earle, points out: "Richard, son of the Black Prince, inherited only his father's outward appearance and none of his skills at war. Not that he was the coward or weakling of legend - on many occasions in his reign he was to display outstanding courage - but his was the courage of pride, not military prowess."

This was reflected in a failed military expedition to Scotland in 1385. This encouraged the French to consider invading England. Charles VI assembled the largest force so far raised by either side during the Hundred Years War. This induced widespread panic and insecurity in England. Parliament met in October 1386, to consider the request from the chancellor, Michael de la Pole, for an unprecedented quadruple subsidy to cover the cost of defence against the threatened invasion. This was refused and the barons began to question the way Richard was ruling the country.

At first Parliament blamed Richard's advisors and his chancellor was impeached by the House of Commons on charges arising out of his conduct in office. De la Pole was found guilty and condemned to imprisonment, but Richard set aside the penalty and he retained his freedom. "Parliament then established a commission which was to hold office for a year and which was to conduct a thorough review of royal finances. It was to have control of the exchequer and the great and privy seals, and Richard was required to take an oath to abide by any ordinances it made."

Richard raised an army against Parliament. Led by Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland it was said to contained no more than 4,000 men. Rumours began to circulate that Richard had agreed to accept military support from France, and that he would place England under French military occupation. Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, and several other nobles, including Henry of Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham, mobilized an army of their retainers numbering 4,500 and marched on de Vere's army. The king's army was defeated at the Battle of Radcot Bridge on 19th December 1387.

Richard was arrested and Woodstock threatened to have him executed because of his dealings with France. They eventually decided against it and instead forcing him to call a session of Parliament. Henry Knighton described it as the Merciless Parliament as it resulted in several of Richard's leading advisors, including Sir Nicholas Brembre, Simon de Burley and Robert Tresilian were executed. Alexander Neville, Archbishop of York, Robert de Vere and Michael de la Pole, all managed to escape to France where they died in exile.

On 3rd May 1389 Richard was allowed back on the throne. This time he made no attempt to revive the style of government which had brought about the crisis of 1387 and for the time being no new inner circle of courtiers emerged to enjoy Richard's favour and patronage. John of Gaunt returned to England in November 1389 and pledged his support to Richard. The atmosphere of peace was to last for six years. During this period he had some diplomatic success. This included a settlement in Ireland in 1394 and two years later negotiated a truce with France.

As soon as he felt strongly enough, Richard fought back against those who were responsible for ousting him from power in 1387. He ordered the arrest of Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, Richard FitzAlan, 11th Earl of Arundel and Thomas de Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick. Gloucester was murdered soon afterwards and Arundel was executed on 21st September, 1397. Warwick made a full confession to attempting to overthrow the king, was banished for life to the Isle of Man.

In June 1399, Henry of Bolingbroke landed at Ravenspurn in Yorkshire. As his army moved across the middle of England, all resistance disappeared. Richard and most of his household knights and the loyal members of his nobility were in Ireland and did not land in Wales until 24th July. Outnumbered, the King surrendered to Henry at Flint Castle, promising to abdicate if his life were spared. Richard was taken to London and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

An assembly opened on 30th September to discuss what was to happen to Richard. His abdication was formally accepted; thirty-nine accusations against him were then read out, and it was agreed that they formed sufficient grounds for his deposition. It was argued that by his actions between 1397 and 1399 Richard had broken his oath and thus broken the legal bond between himself and his people. Article 16 claimed that the king did not "uphold or dispense the rightful laws and customs of the realm, but preferred to act according to his own arbitrary will and do whatever he wished".

Henry was crowned as King Henry IV on 13 October, 1399. Richard remained in the Tower until he was taken to Pontefract Castle in December. It has been suggested that Henry initially intended for Richard to live. However, when he heard from Edward of Norwich, 1st Earl of Rutland, that there was a plot organized by John Montagu, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, John Holland, 1st Earl of Huntingdon, Thomas Holland, 3rd Earl of Kent and Thomas le Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester, to overthrow Henry and put Richard back on the throne, he arranged for him to be murdered. This took place in February, 1400.

On this day in 1540 King Henry VIII marries Anne of Cleves. After the death of Jane Seymour in October 1537, Henry showed little interest in finding a fourth wife. One of the reasons is that he was suffering from impotence. Anne Boleyn had complained about this problem to George Boleyn as early as 1533. His general health was also poor and he was probably suffering from diabetes and Cushings Syndrome. Now in his late 40s he was also obese. His armour from that period reveals that he measured 48 inches around the middle.

However, when Thomas Cromwell told him that he should consider finding another wife for diplomatic reasons, Henry agreed. "Suffering from intermittent and unsatisfied lust, and keenly aware of his advancing age and corpulence" he thought that a new young woman in his life might bring back the vitality of his youth. As Antonia Fraser has pointed out: "In 1538 Henry VIII wanted - no, he expected - to be diverted, entertained and excited. It would be the responsibility of his wife to see that he felt like playing the cavalier and indulging in such amorous gallantries as had amused him in the past."

Cromwell's first choice was Marie de Guise, a young widow who had already produced a son. Aged only 22 she had been married to Louis, Duke of Longueville before his early death in June 1537. He liked the reports that he received that she was a tall woman pleased him. He was "big in person" and he had need of "a big wife". In January 1538 he sent a ambassador to see her. When Marie was told that Henry found her size attractive she is reported to have replied that she might be a big woman, but she had a very little neck. Marie rejected the proposal and married King James V of Scotland on 9th May 1538.

The next candidate was Christina of Denmark, the sixteen-year-old widowed Duchess of Milan. She married Francesco II Sforza, the Duke of Milan at the age of twelve. However, he died the following year. Christina was very well connected. Her father was the former King Christian II of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Her mother, Isabella of Austria, was the sister of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Henry VIII received a promising report from John Hutton. "She is not pure white as (Jane Seymour) but she hath a singular good countenance, and, when she chanceth to smile there appeareth two pits in her cheeks, and one in her chin, the witch becometh her right excellently well." He also compared her to Mary Shelton, one of Henry's former mistresses.

Impressed by Hutton's description, Henry VIII sent Hans Holbein to paint her. He arrived in Brussels on 10th March 1538 and the following day sat for the portrait for three hours wearing mourning dress. However, Christina was disturbed by Henry's treatment of Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn and apparently told Thomas Wriothesley, "If I had two heads, one should be at the King of England's disposal." Wriothesley told Cromwell that he should look for a bride "in some such other place". Henry was very disappointed as he loved the painting and looked at it on a regular basis.

Thomas Cromwell suggested the name of Anne of Cleves, the daughter of John III. He thought this would make it possible to form an alliance with the Protestants in Saxony. An alliance with the non-aligned north European states would be undeniably valuable, especially as Charles V of Spain and François I of France had signed a new treaty on 12th January 1539. As David Loades has pointed out: "Cleves was a significant complex of territories, strategically well placed on the lower Rhine. In the early fifteenth century it had absorbed the neighbouring country of Mark, and in 1521 the marriage of Duke John III had amalgamated Cleves-Mark with Julich-Berg to create a state with considerable resources... Thomas Cromwell was the main promoter of the scheme, and with his eye firmly on England's international position, its attractions became greater with every month that passed."

John III died on 6th February, 1539. He was replaced by Anne's brother, Duke William. In March, Nicholas Wotton, began the negotiations at Cleves. He reported to Thomas Cromwell that "she (Anne of Cleves) occupieth her time most with the needle... She can read and write her own language but of French, Latin or other language she hath none... she cannot sing, nor play any instrument, for they take it here in Germany for a rebuke and an occasion of lightness that great ladies should be learned or have any knowledge of music."

Cromwell was desperate for the marriage to take place but was aware that Wotton's reported revealed some serious problems. The couple did not share a common language. Henry VIII could speak in English, French and Latin but not in German. Wotton also pointed out that she "had none of the social skills so prized at the English court: she could not play a musical instrument or sing - she came from a culture that looked down on the lavish celebrations and light-heartedness that were an integral part of King Henry's court".

Wotton was frustrated by the stalling tactics of William. Eventually he signed a treaty in which the Duke granted Anne a dowry of 100,000 gold florins. However, Henry refused to marry Anne until he had seen a picture of her. Hans Holbein arrived in April and requested permission to paint Anne's portrait. The 23-year-old William, held Puritan views and had strong ideas about feminine modesty and insisted that his sister covered up her face and body in the company of men. He refused to allow her to be painted by Holbein. After a couple of days he said he was willing to have his sister painted but only by his own court painter, Lucas Cranach.

Henry was unwilling to accept this plan as he did not trust Cranach to produce an accurate portrait. Further negotiations took place and Henry suggested he would be willing to marry Anne without a dowry if her portrait, painted by Holbein pleased him. Duke William was short of money and agreed that Holbein should paint her picture. He painted her portrait on parchment, to make it easier to transport in back to England. Nicholas Wotton, Henry's envoy watched the portrait being painted and claimed that it was an accurate representation.

Holbein's biographer, Derek Wilson, argues that he was in a very difficult position. He wanted to please Thomas Cromwell but did not want to upset Henry VIII: "If ever the artist was nervous about the reception of a portrait he must have been particularly anxious about this one... He had to do what he could to sound a note of caution. That meant that he was obliged to express his doubts in the painting. If we study the portrait of Anne of Cleves we are struck by an oddity of composition.... Everything in it is perfectly balanced: it might almost be a study in symmetry - except for the jewelled bands on Anne's skirt. The one on her left is not complemented by another on the right. Furthermore, her right hand and the fall of her left under-sleeve draw attention to the discrepancy. This sends a signal to the viewer that, despite the elaborateness of the costume, there is something amiss, a certain clumsiness... Holbein intended giving the broadest hint he dared to the king. Henry would not ask his opinion about his intended bride, and the painter certainly could not venture it. Therefore he communicated unpalatable truth through his art. He could do no more."

Unfortunately, Henry VIII did not understand this coded message. As Alison Weir, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) has pointed out, the painting convinced Henry to marry Anne. "Anne smiles out demurely from an ivory frame carved to resemble a Tudor rose. Her complexion is clear, her gaze steady, her face delicately attractive. She wears a head-dress in the Dutch style which conceals her hair, and a gown with a heavily bejewelled bodice. Everything about Anne's portrait proclaimed her dignity, breeding and virtue, and when Henry VIII saw it, he made up his mind at once that this was the woman he wanted to marry."

Anne of Cleves arrived at Dover on 27th December 1539. She was taken to Rochester Castle and on 1st January, Sir Anthony Browne, Henry's Master of the Horse, arrived from London. At the time Anne was watching bull-baiting from the window. He later recalled that the moment he saw Anne he was "struck with dismay". Henry arrived at the same time but was in disguise. He was also very disappointed and retreated into another room. According to Thomas Wriothesley when Henry reappeared they "talked lovingly together". However, afterwards he was heard to say, "I like her not".

The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, described Anne as looking about thirty (she was in fact twenty-four), tall and thin, of middling beauty, with a determined and resolute countenance". He also commented that her face was "pitted with the smallpox" and although he admitted there was some show of vivacity in her expression, he considered it "insufficient to counterbalance her want of beauty". Antonia Fraser has argued that Holbein's painting was indeed accurate and Henry's reaction is best explained by the nature of erotic attraction. "The King had been expecting a lovely young bride, and the delay had merely contributed to his desire. He saw someone who, to put it crudely, aroused in him no erotic excitement whatsoever."

Henry VIII asked Thomas Cromwell to cancel the wedding treaty. He replied that this would cause serious political problems. Henry married Anne of Cleves on 6th January 1540. He complained bitterly about his wedding night. Henry told Thomas Heneage that he disliked the "looseness of her breasts" and was not able to do "what a man should do to his wife". Henry later claimed that he doubted Anne's virginity, because she had the fuller figure that he expected a married woman to have, rather than the slimmer one of a maiden.

Two of her ladies-in-waiting, Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford and Eleanor Manners, Countess of Rutland, asked Anne about her relationship with her husband. It became clear that she had not received any sex education. "When the King comes to bed he kisses me and taketh me by the hand, and biddeth me good night... In the morning he kisses me, and biddeth me, farewell. Is not this enough?" She enquired innocently." Further questioning revealled that she was completely unaware of what had been expected of her.

Henry VIII was angry with Thomas Cromwell for arranging the marriage with Anne of Cleves. The conservatives, led by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, saw this as an opportunity to remove him from power. Gardiner considered Cromwell a heretic for introducing the Bible in the native tongue. He also opposed the way Cromwell had attacked the monasteries and the religious shrines. Gardiner pointed out to the King that it was Cromwell who had allowed radical preachers such as Robert Barnes to return to England. The French ambassador reported on 10th April, 1540, that Cromwell was "tottering" and began speculating about who would succeed to his offices. Although he resigned the duties of the secretaryship to his protégés Ralph Sadler and Thomas Wriothesley he did not lose his power and on 18th April the King granted him the earldom of Essex.

In the spring of 1540 Henry VIII met Catherine Howard who had joined the household which had been set up for Queen Anne of Cleves. Alison Weir pointed out that at this time Henry was not in good health: "It had already therefore occurred to her that she might become queen of England, and this was no doubt enough to compensate for the fact that, as a man, Henry had very little to offer a girl of her age. He was now nearing fifty, and had aged beyond his years. The abscess on his leg was slowing him down, and there were days when he could hardly walk, let alone ride. Worse still, it oozed pus continually, and had to be dressed daily, not a pleasant task for the person assigned to do it as the wound stank dreadfully. As well as being afflicted with this, the King had become exceedingly fat: a new suit of armour, made for him at this time, measured 54 inches around the waist." Catherine was able to ignore these problems: "Catherine flattered Henry's vanity; she pretended not to notice his bad leg, and did not flinch from the smell it exuded. She was young, graceful and pretty, and Henry was entranced."

On 6th May, 1540, Henry VIII told Thomas Wriothesley the "King liketh not the Queen, nor ever has from the beginning." Henry asked Thomas Cromwell to find a way out of this problem because he had found a woman who he wanted to become his fifth wife. Cromwell suggested that he should arrange a divorce from Anne. The most obvious reason was the question of non-consummation, in itself this was the clearest cause of nullity by the rules of the church, but it was one that was difficult to establish.

Quarrels in the Privy Council continued and Charles de Marillac reported to François I on 1st June, 1540, that "things are brought to such a pass that either Cromwell's party or that of the Bishop of Winchester must succumb". On 10th June, Cromwell arrived slightly late for a meeting of the Privy Council. Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, shouted out, "Cromwell! Do not sit there! That is no place for you! Traitors do not sit among gentlemen." The captain of the guard came forward and arrested him. Cromwell was charged with treason and heresy. Norfolk went over and ripped the chains of authority from his neck, "relishing the opportunity to restore this low-born man to his former status". Cromwell was led out through a side door which opened down onto the river and taken by boat the short journey from Westminster to the Tower of London.

On 12th June, Thomas Cranmer wrote a letter to Henry VIII saying he was amazed that such a good servant of the king should be found to have committed treason. He pointed out that he had shown "wisdom, diligence, faithfulness and experience as no prince in the realm ever had". Cranmer told Henry that he loved Cromwell as a friend, "but I chiefly loved him for the love which I thought I saw him bear ever towards your grace singularly above all others. But now if he be a traitor, I am sorry that ever I loved him or trusted him, and I am very glad that his treason has been discovered in time. But yet again I am very sorrowful, for whom should your grace trust hereafter."

Thomas Cromwell was convicted by Parliament of treason and heresy on 29th June and sentenced him to be hung, drawn and quartered. He wrote to Henry VIII soon afterwards and admitted "I have meddled in so many matters under your Highness that I am not able to answer them all". He finished the letter with the plea, "Most gracious prince I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy." Henry commuted the sentence to decapitation, even though the condemned man was of lowly birth.

Anne of Cleves feared that her life was in danger. However, Henry made it clear that he was willing to accept an annulment of his marriage based on his inability to consummate the relationship. This was because he feared that she was the wife of another man, Francis, Duke of Lorraine. "His lawyers had to argue that his problem was relative impotence, an incapacity limited to one woman. This was often put down to witchcraft. But publicly the annulment was justified by reference to Henry's decision to refrain from consummation until he had ascertained that Anne was free to marry him, to Anne's contract with the son of the duke of Lorraine, and to Henry's reluctance to wed her."

After she made a statement that confirmed Henry's account, the marriage was annulled on 9th July 1540, on the grounds of non-consummation. Anne of Cleves received a generous settlement that included manor and estates, some of which had been recently forfeited by Cromwell, worth some £3,000 a year. In return, Anne agreed that she would not pass "beyond the sea" and became the King's adopted "good sister". It was important for Henry that Anne remained in England as he feared that she might stir up trouble for him if she was allowed to travel to Europe.

On 21st July, 1540, Marillac was reporting that the marriage was over because of Henry's relationship with Catherine Howard: "The Queen appears to make no objection. The only answer her brother's ambassador can get from her is that she wishes in all things to please the King her lord, bearing testimony of his good treatment of her, and desiring to remain in this country. This, being reported to the King, makes him show her the greater respect."

After the execution of Catherine Howard in 1542, Anne of Cleves, hoped to remarry Henry VIII. It was reported that Duke William initiated discussions but the King quickly rejected the idea. They did exchange gifts that Christmas but became deeply depressed when he neglected to communicate with her. The problem became worse when he married Catherine Parr in July 1543. Henry responded by granting her more land. After his death on 28th January, 1547, Anne longed to return home and informed her brother that "England was not her country and that she was a stranger there".

Anne of Cleves suffered financial distress during the reigns of Henry's children. In 1547 the Privy Council of Edward VI confiscated Richmond and Bletchingley. Anne was allowed to attend the coronation of Queen Mary and on 4th August 1553, she wrote to congratulate her on her marriage to Philip of Spain. In an attempt to please Mary she became a Roman Catholic. Anne of Cleves died on 16th July 1557.

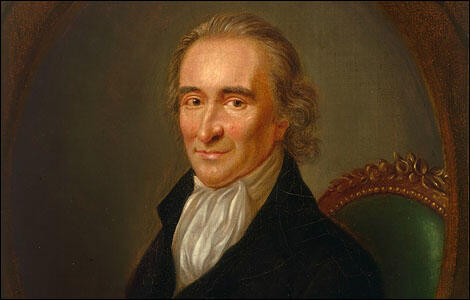

On this day in 1793 the Sunday Observer newspaper launched an attack on Tom Paine. The execution of the positive and systematic incendiary Tom Paine, is now become as general and as favourable an amusement among the schoolboys of London, as the execution of that uncertain and preposterous incendiary, Guy Fawkes, has been for many years. We have the pleasure of seeing him on fire every day: would we could totally extinguish the flames which his wicked and absurd writings have too fatally kindled in the minds of weak and mischievous individuals."

On this day in 1799 Jedediah Smith, the son of a general store owner, was born at Bainbridge, New York. His parents were Methodists and as a young man he developed strong religious beliefs. In 1810 His family moved to Erie County, Pennsylvania. He developed an interest in travel after reading about the travels of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, overland to the Pacific Ocean.

Smith moved to St. Louis in search of work. On 13th February, 1822, William Ashley placed an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Adviser where he called for 100 enterprising men to "ascend the river Missouri" to take part in the fur collecting business. Those who agreed to join the party included Smith, Tom Fitzpatrick, Hugh Glass, Jim Beckwourth, David Jackson, William Sublette and James Bridger.

On 30th May, 1823, William Ashley and his party of 70 men were attacked by 600 Arikara. Twelve of Ashley's men were killed and the rest were forced to retreat. Smith volunteered to contact Andrew Henry and bring back reinforcements. A message was sent back to Colonel Henry Leavenworth of the U.S. Sixth Infantry and later 200 soldiers and 700 Sioux allies attacked the Arikara villages.

In 1824 Smith led a small group of men south of the Yellowstone to open up new trapping grounds. During the journey he discovered the South Pass through the Rocky Mountains at Wyoming. Smith was also badly mauled by a bear. The animal ripped Smith's scalp open and for the rest of his life he brushed his hair forward to conceal the scar. The trip was a great success and Smith returned to St. Louis in 1825 with 9,000 pounds of beaver skin.

A devout Methodist, it was said of Smith that "his Bible and his rifle were his inseparable companions." Another mountain man, William Waldo, said that Smith was "a bold, outspoken, professing, and consistent Christian, the first and only one known among the early Rocky Mountain trappers and hunters." Smith was also an outstanding trapper and the 668 pelts he took in the 1824-1825 season was a record haul.

William Ashley, who described Smith as a "a very intelligent and confidential young man", now made him a partner in his business and together they pioneered the Oregon Trail to the mountains. In 1826 Smith joined forces with David Jackson and William Sublette to buy out Ashley. Whereas Sublette and Jackson worked the central Rockies, Smith decided to search out new trapping grounds in the southwest. In August 1826, Smith and a 15 men team headed for the Wasatch Mountains. During this journey they became the first American pioneers to meet the Wintu.

Jedediah Smith wrote about his travels in his journal: "I have at different times suffered the extremes of hunger and thirst. Hard as it is to bear for successive days the knawings of hunger, yet it is light in comparison to the agony of burning thirst and, on the other hand, I have observed that a man reduced by hunger is some days in recovering his strength. A man equally reduced by thirst seems renovated almost instantaneously. Hunger can be endured more than twice as long as thirst. To some it may appear surprising that a man who has been for several days without eating has a most incessant desire to drink, and although he can drink but little at a time, yet he wants it much oftener than in ordinary circumstances."

After crossing the Colorado River the men entered the Black Mountains of Arizona. Smith was unable to find "beaver water" and instead of retracing his steps decided to cross the Mojave Desert in California. It took the party 15 days to cross this flat, salt-crusted plain under a blazing sun. Eventually they arrived at what is now Los Angeles. As Kevin Starr has pointed out that "the Smith party constituted the first American penetration of California overland from the east."

This area was under the control of Mexico and Smith and his party were arrested and kept at San Diego until January, 1827. The group then wintered in the San Joaquin Valley. In May, Smith took his men across the Sierra Nevada mountains. The deep snow halted the first attempt and when he tried for a second time, Smith only had two companions. This time he managed to cross the mountains through what is now known as Ebbetts Pass. The three men therefore became the first white men to achieve this feat.

The desert east of the Sierra caused Smith and his companions serious problems. On 24th June Smith wrote in his diary: "With our best exertion we pushed forward, walking as we had been for a long time, over the soft sand. That kind of traveling is very tiresome to men in good health who can eat when and what they choose, and drink as often as they desire, and to us, worn down with hunger and fatigue and burning with thirst increased by the blazing sands, it was almost insupportable."

On 25th June one of the men, Robert Evans, did not have the strength to continue. Smith and the other man went on ahead. Smith wrote in his diary: "We left him and proceeded onward in the hope of finding water in time to return with some in season to save his life. After traveling about three miles we came to the foot of the mountain and there, to our inexpressible joy, we found water."

The three men eventually reached Bear Lake. Smith now wrote to William Clark about his trip and what he had discovered. In his letter he explained how he had discovered "a country which has been, measurably, veiled in obscurity, and unknown to the citizens of the United States."On 13th June Smith assembled a new party of 18 men and two women to go back to California. He decided to use the same route as before. While crossing the Colorado River the party was attacked by members of the Mojave tribe. Ten of the men were killed and the two women were captured. Smith and the seven remaining men reached California in late August. Once again Smith was arrested by the Mexican authorities. He was eventually released after he promised he would leave California and not return.

Smith and his party now explored northward into Oregon in search of promising beaver trapping areas. On 14th July, 1828, while Smith and two other members of his party were off on a scouting trip on the Umpqua River, the Kelawatset tribe attacked the camp and killed 15 of his men. Alexander Roderick McLeod returned and recorded the poignant scene in his journal: “... at the entrance of the North Branch, where Mr. Smith's party were destroyed, and a sad spectacle of Indian barbarity presented itself to our view, the skeletons of eleven of those miserable sufferers lying bleaching in the sun.”

Jedediah Smith and what remained of his party eventually reached Fort Vancouver in Canada. During a three year period Smith had taken 33 men with him on his expeditions to California. Of these, 26 had been killed. Kevin Starr, the author of California (2005) has argued: "Smith's heroic journey - the double encirclement of the Far West - was the physical, moral, and geopolitical equivalent of the great voyages of exploration off the California coast in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The Spaniards linked California to the sea; Smith linked California to the interior of the North American continent."

Smith spent the winter of 1828-29 at Fort Vancouver. In March, his party, that included James Bridger, journeyed east to meet up with David Jackson and his trappers on the Clark Fork River. The two trapping parties reached Pierre's Hole in August. The following year Smith and his partners sold their business to the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Smith returned to St. Louis in 1830 with the idea of making maps of the areas he had explored. He found it impossible to settle and in 1831 he agreed to guide 22 wagons on a trading expedition to Sante Fe. Smith made a crucial mistake of not making sure that the party had taken sufficient supplies of water. On 27th May 1831, Jedediah Smith decided to travel ahead in search of water. He was set upon by 20 Comanches and was killed.

Dan L. Thrapp has argued: "Smith was more than 6 feet tall, spare, a man of great courage, vision, dedication and persistence... His contributions to geographical knowledge of the west, and his pioneering expeditions were of great value; his journals and records suggest that he intended at some time to publish his findings, but his early and lamented death aborted that plan."

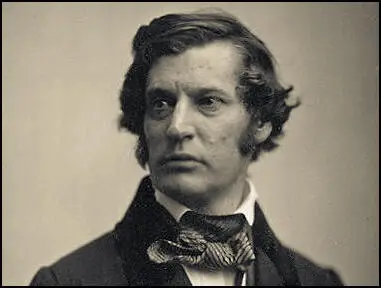

On this day in 1811 Charles Sumner, the son of a lawyer, was born in Boston, Massachusetts. After graduating from Harvard University in 1833 he was admitted to the bar. Sumner developed radical political opinions and after reading An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans by Lydia Maria Child he became active in the campaign against slavery. Sumner also advocated education and prison reform.

Sumner joined the Whig Party but in 1848 helped to form the Free Soil Party. The following year he made a legal challenge against segregated schools in Boston. In 1851, with the support of the Democratic Party, Sumner was elected to Congress. He now became the Senate's leading opponent of slavery. After one speech Sumner made against pro-slavery groups in Kansas in 1856 he was beaten unconscious by Preston Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina. His injuries stopped him from attending the Senate for the next three years.

During the secession crisis in 1860-61, Sumner argued against any compromise deal and became one of the leaders of the Radical Republicans in Congress. On the outbreak of the American Civil War, he advocated the use of black troops to bring an end to slavery. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Sumner showed considerable political skill in preventing European intervention in the conflict.

Sumner clashed with Abraham Lincoln over his treatment of Major General John C. Fremont. On 30th August, 1861, Fremont, the commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. Lincoln asked Fremont to modify his order and free only slaves owned by Missourians actively working for the South. When Fremont refused, he was sacked and replaced by the conservative General Henry Halleck. Sumner wrote to Lincoln complaining about his actions and remarked how sad it was "to have the power of a god and not use it godlike".

The situation was repeated in May, 1863, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied districts of South Carolina. Soon afterwards Hunter issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in the area were free. Abraham Lincoln was furious and instructed him to disband the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment and to retract his proclamation. Sumner supporting Hunter telling Lincoln that the Union could only be saved by freeing the slaves.

Charles Sumner also disagreed with Abraham Lincoln over suffrage. Sumner wanted all African Americans to have the vote whereas Lincoln favoured partial enfranchisement. Sumner thought that universal suffrage would help the government arguing that "the only Unionists of the South are black". Despite their many disagreements, the two men remained close friends. On one occasion Lincoln told Sumner "the only difference between you and me is a difference of a month or six weeks in time."

Despite their insistance that the white power structure in the South should be removed, most Radical Republicans argued that the deated forces should be treated leniently. Even while the American Civil War was going on Sumner argued that: "A humane and civilised people cannot suddenly become inhumane and uncivilized. We cannot be cruel, or barbarous, or savage, because the Rebels we now meet in warfare are cruel, barbarous and savage. We cannot imitate the detested example."

In 1866 Sumner and the Radical Republicans advocated the passing of the Civil Rights Bill, legislation that was designed to protect freed slaves from Southern Black Codes (laws that placed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations).

Charles Sumner also opposed the policies of President Andrew Johnson and argued in Congress that Southern plantations should be taken from their owners and divided among the former slaves. They also attacked Johnson when he attempted to veto the extension of the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. However, the Radical Republicans were able to get the Reconstruction Acts passed in 1867 and 1868. Sumner also urged an extensive programme of economic aid, land distribution and free education for freed slaves.

In November, 1867, the Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 that Andrew Johnson be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors. The majority report written by George H. Williams contained a series of charges including pardoning traitors, profiting from the illegal disposal of railroads in Tennessee, defying Congress, denying the right to reconstruct the South and attempts to prevent the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On 30th March, 1868, Johnson's impeachment trial began. Sumner led the attack arguing that: "This is one of the last great battles with slavery. Driven from the legislative chambers, driven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found a refuge in the executive mansion, where, in utter disregard of the Constitution and laws, it seeks to exercise its ancient, far-reaching sway. All this is very plain. Nobody can question it. Andrew Johnson is the impersonation of the tyrannical slave power. In him it lives again. He is the lineal successor of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis; and he gathers about him the same supporters."

Sumner was bitterly disappointed when the Senate vote was one short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction. Sumner and other Radical Republicans were angry that not all the Republican Party voted for a conviction and Benjamin Butler claimed that Johnson had bribed two of the senators who switched their votes at the last moment.

President Ulysses S. Grant was also criticised by Sumner for not doing more for black civil rights. This upset senior members of the Republican Party and he was removed as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee. Sumner lost all faith in Grant and in the 1872 presidential election he supported his rival, Horace Greeley. Charles Sumner died of a heart attack on 11th March, 1874.

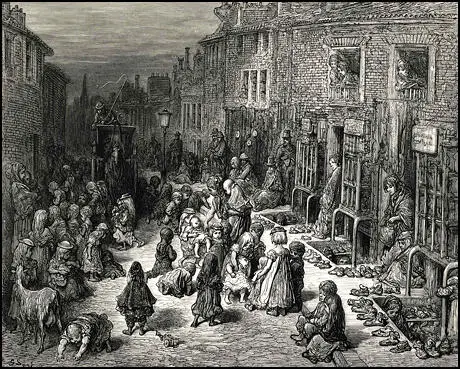

On this day in 1832 Gustave Doré, the second of the three children of Pierre Louis Christophe Doré, an engineer, and his wife, Alexandrine Marie Anne Pluchart, was born in Strasbourg. His biographer, David Kerr, has pointed out: "A child prodigy, Doré received little formal artistic training, but his talents as a draughtsman were already apparent during his school years."

Dore's first lithographic album was published by in Paris in 1847. He worked as a caricaturist until gaining fame as an illustrator in 1854 after working on a book by François Rabelais. Other commissions included work by Honoré de Balzac, Dante Alighieri, Miguel de Cervantes and John Milton. In 1863 he was asked to illustrate the works of Lord Byron. This was followed by other work for British publishers including a new illustrated Dore's English Bible (1865). According to Kerr: "The speed with which he drew was legendary and his output was as noteworthy for its quantity as for its quality."

in 1867 Gustave Dore had a major exhibition of his work in London. This led to the foundation of the Dore Gallery in New Bond Street. In 1869, Blanchard Jerrold, the son of Douglas Jerrold, suggested that they worked together to produce a comprehensive portrait of London. Jerrold had got the idea from The Microcosm of London, that had been produced by Rudolf Ackermann, William Pyne and Thomas Rowlandson in 1808.

Dore signed a five-year project with he publishers, Grant & Co, that involved him staying in London for three months a year. Dore was paid the vast sum of £10,000 a year for the proposed art work. The book, London: A Pilgrimage, with 180 engravings by Dore, was eventually published in 1872.

Although a commercial success, many of the critics disliked the book. Several were upset that Dore had appeared to concentrate on the poverty that existed in London. Gustave Dore was accused by the Art Journal of "inventing rather than copying". The Westminster Review claimed that " Dore gives us sketches in which the commonest, the vulgarest external features are set down".

London: A Pilgrimage was a financial success and Dore received commissions from other British publishers. Dore's later work included Paradise Lost, King Arthur: The Idylls of the King and The Works of Thomas Hood. His work also appeared in the Illustrated London News. Gustave Doré continued to illustrate books until his death on 23rd January 1883.

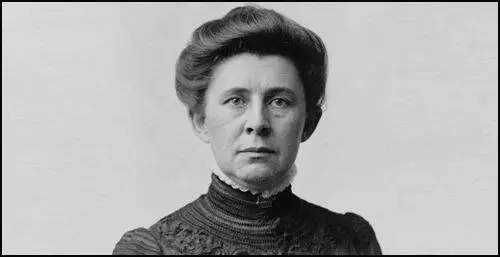

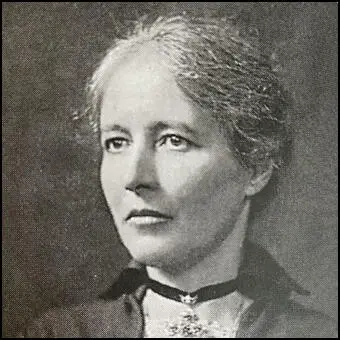

On this day in 1878 the birth of Marian Ellis and Edith Ellis, twin daughters John Ellis and Maria Rowntree Ellis, was born in Nottingham. Both her parents were members of the Society of Friends and her father was Liberal Party MP for Rushcliffe (1885-1910) and was a strong opponent of the Boer War. During the conflict Ellis became involved in the Quaker relief projects for women victims of the conflict.

Ellis and her sister, Edith Ellis, were both opposed to the First World War and following a letter from Fenner Brockway and Lilla Brockway that appeared in Labour Leader, the newspaper of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) was formed.

The peace movement feared the introduction of conscription. "Although conscription may not be so imminent as the Press suggests, it would perhaps be well for men of enlistment age who are not prepared to take the part of a combatant in the war, whatever be the penalty for refusing to band themselves together as we may know our strength. As a preliminary, if men between the years of 18 and 38 who take this view will send their names and addresses to me at the addresses given below a useful record will be at our service."

Marian Ellis argued in a pamphlet, Looking Towards Peace (1915): "War, tyranny and revolt have produced tyranny, revolt and war throughout time... We maintain that the moral law is binding upon States as upon individuals... We hold that the fundamental interests of humanity are one... the reasoned worship of force is the real devil-worship."

The National Committee of the NCF included Clifford Allen, Fenner Brockway, Catherine Marshall (Secretary), Bertrand Russell (chairman) and Alfred Salter (Treasurer). Ada Salter and Violet Tillard were placed in charge of Maintenance for the families of conscientious objectors. This project was largely funded by Marion and her sister Edith, who donated "huge sums of money".

On the outbreak of the First World War a group of women pacifists in the United States began talking about the need to form an organization to help bring it to an end. On the 10th January, 1915, over 3,000 women attended a meeting in the ballroom of the New Willard Hotel in Washington and formed the Woman's Peace Party. In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited members of the Woman's Peace Party and suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Marion Ellis, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Maude Royden, Mary Sheepshanks, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. The historian, Richard J. Evans described the founders of WILPF as "a tiny band of courageous and principled women on the far-left fringes of bourgeois-liberal feminism ".

In her pamphlet, Disarmament (1917) she discussed the post-war world: "At the end of this war she would will have to decide which way it desires to go, towards disarmament or destruction... Disarmament is not merely scrapping our guns and our battleships. It is the working out of a national policy, which, being inspired by love for all men, cannot be antagonistic... It is the problem of India, of Ireland, of our relations with Russia and Persia, Germany and Belgium as God would have them to be."

Marian's twin sister, Edith Ellis, was also a financial supporter of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF). In May 1918, Ellis was prosecuted under the Defence of the Realm Act, for her involvement in the publishing a pamphlet titled A Challenge to Militarism without submitting it to the Censor. The Society of Friends stated that "We feel that the declaration of peace and goodwill is the duty of all Christians and ought not to be dependent upon the permission of any Government Official. We therefore intend to continue the publication of such leaflets as we feel it our duty to put forth, without submitting them to the Censor."

In court, Edith Ellis stated that "because of our religious belief, we do not feel it right to submit the outcome of our deliberations to an official of Government. We believe we must act in accordance with the dictates of God, ourselves." When Edith spoke "the court was visibly impressed as, with the timbre of her woman's voice, she told in calm words of her immutable conviction." Edith was fined £100 with 50 guineas costs and subject to three months in prison on default of paying the fine, which she refused to do and it is claimed that she suffered poor health because of time in Holloway Prison.

Marian Ellis helped to establish the Fight the Famine Committee. She also played a significant role in the campaign against disarmament: "The enormous development of the power of armaments both during and since the great war has brought mankind within measurable distance of destruction."

In 1919 Ellis helped to establish the Fight the Famine Council in an effort to persuade the British government to end the Allied Bockade imposed on the defeated countries. On 15 April 1919, the Council set up a fund to raise money for the German and Austrian children – the Save the Children Fund. During this time Marian became friends with Charles Alfred Cripps, 1st Baron Parmoor, the President of the organisation.

Marian Ellis and Edith Ellis had moved away from their parents liberalism and were now Christian Socialists. Charles Cripps had been the Conservative MP for Wycombe (1910-1914) and was now in the House of Lords and was the brother-in-law of Beatrice Webb. On 14th July, 1919, Marian Ellis married Parmoor. Webb commented: "He has excellent taste in women. He choose the most charming of the Potter sisters... and he has now won an exceptionally attractive woman, good as gold, able and most pleasant to look at. All his children and their mates were there beaming goodwill. The two were reverently ecstatic."

Marian Ellis managed to convert her new husband to socialism. According to one friend, Parmour became "something very like an international socialist" After joining the Labour Party he became the leader of the House of Lords from 1928-1931. The marriage was childless, but Lady Parmoor strongly influenced her youngest stepson, Richard Stafford Cripps who went on to be a senior figure in the post-war Labour government.

Lord and Lady Parmoor were great supporters of the League of Nations. After the war Lord Parmoor served as the country's chief representative at Geneva. Richard Stafford Cripps said that "the injustice wrought upon the common people had convinced him that some new outlook was necessary if civilisation were to be saved from destruction."

From 1924 to 1928 Lady Parmoor was president of the World YWCA and she helped found the Fellowship of Reconciliation. A founder member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, she became president of its British section in 1950. She was also treasurer of the Friends' Peace Committee and an active vice-president of the National Peace Council.

Lady Parmoor was a supporter of Mahatma Gandhi . After the collapse in October 1931 of the Second Round Table Conference she helped establish the India Conciliation Group. Other members of the group included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Maude Royden, Charles Freer Andrews, Hewlett Johnson, Agatha Harrison and Alexander Cowan Wilson.

Lord and Lady Parmoor both became great admirers of George Lansbury and his book, My England (1934). Lord Parmoor wrote to his son, Richard Stafford Cripps, soon after the book was published: "George Lansbury spent yesterday at Parmoor, much to the delight of Marion and myself.... You know that I have a great admiration for him and his book (My England). It is a powerful work... His views on the general outlook are and always have been similar to my own."

In the late 1930s Lord Parmoor's health deteriorated and he died aged 89 on 30th June, 1940. Beatrice Webb commented: "In the last years of decrepitude he was something of an egotist, and poor devoted Marion had a hard time of it. But in spite of a strong strain of personal egotism, Alfred was essentially a good man."

Lady Parmoor advocated the admission of communist China to the United Nations, she urged an end by negotiation to the Korean War, and at the age of seventy she began a serious study of nuclear fission in order to speak with some authority about the uses and dangers of atomic energy. Her last political act, two days before her death, was to help draft a Quaker message to the prime minister protesting against the aerial bombardment of North Korea.

On this day in 1914 bailiffs arrive at the home of Sophia Duleep Singh and take away a necklace and gold bangle to pay her tax debts. Sophia Duleep Singh was one of the first women to sign up as someone willing to be a tax resister. She knew that this was a dangerous move. The courts warned the women that if they refused to pay, they risked the enforced seizure and sale of their property and the worst offenders would be sent to prison.

In May 1911, at Spelthorne petty sessions, Sophia Duleep Singh's refusal to pay licences for her five dogs, carriage, and manservant led to a fine of £3. In July 1911, against arrears of 6s. in rates, she had a seven stone diamond ring impounded and auctioned at Ashford for £10. The ring was bought by a member of the Women's Tax Resistance League and returned to her.

In December 1913 she was summoned again to Feltham police court for not paying her taxes. "The Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, residing at Hampton Road, Hampton Court, attended at Feltham Police Court yesterday upon summonses for refusing to pay taxes... She employed a groom without a licence, and also kept two dogs and a carriage without payment of the necessary licence. She came to court wearing the badge and medal of the Tax Resistance League and was accompanied by six other ladies including the secretary of the league, Mrs Kineton Parkes."

In court she made a statement explaining her reasons for not paying her taxes: "I am unable conscientiously to pay money to the state, as I am not allowed to exercise any control over its expenditure, neither am I allowed any voice in the choosing of members of Parliament, whose salaries I have to help to pay. This is very unjustified. When the women of England are enfranchised and the State acknowledges me as a citizen, I shall, of course, pay my share willingly towards its upkeep, if I am not a fit person for the purposes of representation, why should I be a fit person for taxation?"

Sophia Duleep Singh's refusal to pay a fine of £12 10s. resulted in a pearl necklace, comprising 131 pearls, and a gold bangle studded with pearls and diamonds, being seized under distraint and auctioned at Twickenham town hall, both items being bought by members of Women's Tax Resistance League, the necklace fetching £10 and the bangle £7. "Such actions were a means of achieving publicity. Members of the WTRL, by buying articles under distraint, and organizing protest demonstrations and meetings after the auction, generated interest and sympathy in the movement."

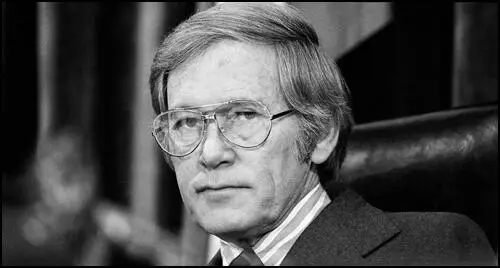

On this day in 1915 Don Edwards was born in San Jose, California. After being educated at Stanford University Edwards was admitted to the bar in 1940. He worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation for a year before becoming a lawyer.

Edwards joined the United States Navy as a gunnery officer in 1942. He also worked in naval intelligence during the Second World War.

In 1951 Edwards became president of the Valley Title Company. A member of the Democratic Party, Edwards was elected to the 88th Congress in November, 1962. Edwards was one of those politicians who questioned the conclusions of the Warren Commission Report.

As chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights he interviewed key figures in the FBI involved in the investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He discovered that Gordon Shanklin had ordered FBI agent, James Hosty, to destroy the letter written by Lee Harvey Oswald. He also found out that the FBI had been in contact with Jack Ruby at least seven times between a visit to Cuba in 1959 and the events in Dallas in 1963.

In 1975 Richard Case Nagell contacted Don Edwards to tell him about "a registered letter that I dispatched to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in September 1963, informing him of a conspiracy involving Oswald and two Cuban refugees to assassinate President Kennedy".

Edwards told a group of Congressmen in 1976 that: "There's not much question that both the FBI and CIA are somewhere behind this cover-up. I hate to think what it is they are covering-up - or who they are covering for."

Don Edwards retired from Congress in 1995. He died on 1st October, 2015.

On this day in 1907 Maria Montessori opened her first school. Maria Montessori was born in Italy on 31st August, 1870. After graduating from medical school in 1896 Montessori became the first woman in Italy to become a doctor.

Montessori returned to university in 1901 to study psychology and philosophy. Three years later she became professor of anthropology at the University of Rome.

In 1906 Montessori left the university in order to work with sixty young working class children in the San Lorenzo district of Rome. Soon afterwards she founded the Casa dei Bambini (Children's House) where she developed what became known as the Montessori method of education. This method of teaching was based on spontaneity of expression and freedom from restraint.

In 1913 Montessori went to the United States where with the help of Alexander G. Bell founded the Montessori Educational Association in Washington. She also joined with Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, Mabel Vernon, Olympia Brown, Mary Ritter Beard, Belle LaFollette, Helen Keller, Dorothy Day and Crystal Eastman to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS).

Montessori established a research institute in Spain and in 1919 she began a series of teacher training courses in London. In 1922 she was appointed a government inspector of schools in Italy.

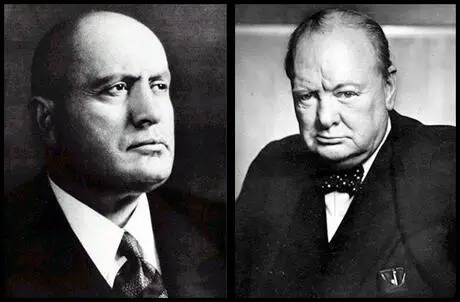

An opponent of Benito Mussolini, Montessori was forced to leave Italy in 1934. She moved to Spain until General Francisco Franco and his nationalist forces defeated the republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

Montessori established training centres in the Netherlands (1938), India (1939) and England (1947). Maria Montessori, who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949, 1950 and 1951, died in Noordwijk, Holland, on 6th May, 1952.

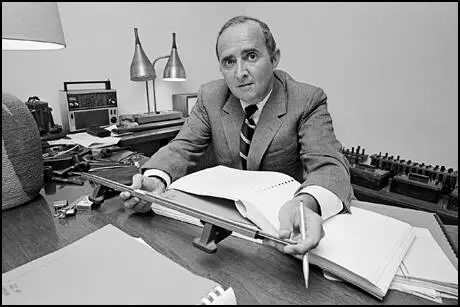

On this day in 1921 Louis Harris was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He attended New Haven High School and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he graduated in 1942.

In 1947 Harris went to work for Elmo Roper. Initially he worked as Roper's assistant in his marketing research company. However, Roper was against working for politicians. He argued: "I think prediction of elections is a socially useless function. Marketing research and public opinion research have demonstrated that they are accurate enough for all possible commercial and sociological purposes. We should protect from harm this infant science which performs so many socially useful functions, but which could be wrong in predicting elections, particularly in a year like this."