Black Codes

Black Codes was a name given to laws passed by southern governments that imposed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations.

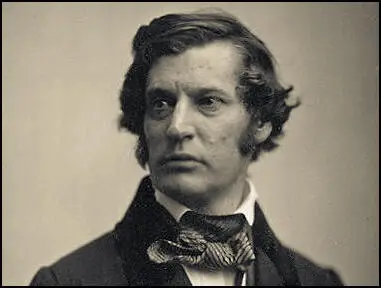

On 7th July, 1862, Charles Sumner attacked the decision by President Abraham Lincoln to allow Black Codes to continue. "A government organized by Congress and appointed by the President is to enforce laws and institutions, some of which are abhorrent to civilization. Take for instance, the Revised Code of North Carolina, which I have before me. "Any free person, who shall teach, or attempt to teach, any slave to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or shall give or sell to such slave any book or pamphlet, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, if a white man or woman, shall be fined not less than one hundred nor more than two hundred dollars, or imprisoned, and if a free person of colour, shall be fined, imprisoned, or whipped not exceeding thirty-nine nor less than twenty lashes."

After the American Civil War the Radical Republicans advocated the passing of the Civil Rights Bill, legislation that was designed to protect freed slaves from Southern Black Codes (laws that placed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations).

In April 1866, President Andrew Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Bill. Johnson told Thomas C. Fletcher, the governor of Missouri: "This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men." His views on racial equality was clearly defined in a letter to Benjamin B. French, the commissioner of public buildings: "Everyone would, and must admit, that the white race was superior to the black, and that while we ought to do our best to bring them up to our present level, that, in doing so, we should, at the same time raise our own intellectual status so that the relative position of the two races would be the same."

Radical Republicans repassed the Civil Rights Bill and were also able to get the Reconstruction Acts passed in 1867 and 1868. Despite these acts, white control over Southern state governments was gradually restored when organizations such as the Ku Kux Klan were able to frighten blacks from voting in elections.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) In a speech made on 7th July, 1862, Charles Sumner attacked the decision by President Abraham Lincoln to allow Black Codes to continue.

A government organized by Congress and appointed by the President is to enforce laws and institutions, some of which are abhorrent to civilization. Take for instance, the Revised Code of North Carolina, which I have before me. "Any free person, who shall teach, or attempt to teach, any slave to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or shall give or sell to such slave any book or pamphlet, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, if a white man or woman, shall be fined not less than one hundred nor more than two hundred dollars, or imprisoned, and if a free person of colour, shall be fined, imprisoned, or whipped not exceeding thirty-nine nor less than twenty lashes.

Here is another specimen: "If any person shall willfully bring into the State, with an intent to circulate, or shall aid or abet the bringing into, or the circulation or publication, the State, any written or printed in or out of the State, the evident tendency whereof is to cause slaves to become discontented with the bondage in which they are held by their masters and the laws regulating the same, and free negroes to be dissatisfied with their social condition and the denial to them of political privileges, and thereby to excite among the said slaves and free negroes a disposition to make conspiracies, insurrections, or resistance against the peace and quiet of the public, such person so offending shall be deemed guilty of felony, and on conviction thereof shall, for the first offence, be imprisoned not less than one year, and be put in the pillory and whipped, at the discretion of the court, and for the second offence shall suffer death."

(2) Andrew Johnson, letter to William Sharkey, the governor of Mississippi (June, 1865)

If you could extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution of the United States in English and write their names and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at not less than two hundred and fifty dollars and pay taxes thereon, and would completely disarm the adversary. This you can do with perfect safety. And as a consequence, the radicals, who are wild upon negro franchise, will be completely foiled in their attempts to keep the Southern States from renewing their relations to the Union.

(3) Report on the work of the Freemen's Bureau that was signed by General Oliver Howard and Salmon P. Chase (August, 1867)

The abolition of slavery and the establishment of freedom are not the one and the same thing. The emancipated negroes were not yet really freemen. Their chains had indeed been sundered by the sword, but the broken links still hung upon their limbs. The question, "What shall be done with the negro? agitated the whole country. Some were in favour of an immediate recognition of their equal and political rights, and of conceding to them at once all the prerogatives of citizenship. But only a few advocated a policy so radical, and, at the same time, generally considered revolutionary, while many, even of those who really wished well to the negro, doubted his capacity for citizenship, his willingness to labour for his own support, and the possibility of his forming, as a freeman, an integral part of the Republic.

The idea of admitting the freedmen to an equal participation in civil and political rights was not entertained in any part of the South. In most of the States they were not allowed to sit on juries, or even to testify in any case in which white men were parties. They were forbidden to own or bear firearms, and thus were rendered defenceless against assault. Vagrant laws were passed, often relating only to the negro, or, where applicable in terms of both white and black, seldom or never enforced except against the latter.

In some States any court - that is, any local Justice of the Peace - could bind out to a white person any negro under age, without his own consent or that of his parents? The freedmen were subjected to the punishments formerly inflicted upon slaves. Whipping especially, when in some States disfranchised the party subjected to it, and rendered him for ever infamous before the law, was made the penalty for the most trifling misdemeanor.

These legal disabilities were not the only obstacles placed in the path of the freed people. Their attempts at education provoked the most intense and bitter hostility, as evincing a desire to render themselves equal to the whites. Their churches and schoolhouses were in many places destroyed by mobs. In parts of the country remote from observation, the violence and cruelty engendered by slavery found free scope for exercise upon the defenceless negro. In a single district, in a single month, forty-nine cases of violence, ranging from assault and battery to murder, in which whites were the aggressors and blacks the sufferers, were reported.

(4) Robert E. Lee was cross-examined by Jacob Howard, the senator from Michigan, as a Congressional committee held on 17th February, 1866. Howard asked Lee if he believed the "colored population" should vote in elections.

My own opinion is that, at this time, they cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the right of suffrage would open the door to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways. What the future may prove, how intelligent they may become, with what eyes they may look upon the interests of the state in which they may reside, I cannot say more than you can.

(5) Thaddeus Stevens, wrote his own epitaph that appeared on his tombstone in an African American cemetery.

I repose in this quiet and secluded spot, not from any natural preference for solitude; but finding other cemeteries limited as to race, by charter rules, I have chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life, equality of man before the Creator.

(6) J. L. Alcorn, letter to Elihu Washburne (29th June, 1868)

Can it be possible that the Northern people have made the negro free, but to be returned, the slave of society, to bear in such slavery the vindictive resentments that the satraps of Davis maintain today towards the people of the north? Better a thousand times for the negro that the government should return him to the custody of the original owner, where he would have a master to look after his well being, than that his neck should be placed under the heel of a society, vindictive towards him because he is free.