Sioux

The Sioux lived over a vast area of North America. The name Sioux is a French abbreviation of the Algonquin word meaning enemy. The Sioux themselves tended to describe themselves as Dakota or Lakota. The Sioux were divided into different tribes. This included the Oglala, Hunkpapa, Brule, Santee, Sans Arcs, Minnwkonjou, Mdewakantonwan, Yankton, Yanktonai, Wahpekute, Sisseton and Wahpeton.

The Oglalas were the most numerous and offered the most resistance to white settlers. In June 1866, Red Cloud, chief of the Oglalas, began negotiating with the army based at Fort Laramie about the decision to allow emigrants to settle on the last of the great Sioux hunting grounds. When he was unable to reach agreement with the army negotiators he resorted to sending out war parties that attacked emigrants and army patrols. These hit and run tactics were difficult for the army to deal with and be the time they arrived on the scene of the attack the war parties had disappeared.

On 21st December, 1866, Captain W. J. Fetterman and an army column of 80 men, were involved in protecting a team taking wood to Fort Phil Kearny. Although under orders not to "engage or pursue Indians" Fetterman gave the orders to attack a group of Sioux warriors. The warriors ran away and drew the soldiers into a clearing surrounded by a much larger force. All the soldiers were killed in what became known as the Fetterman Massacre. Later that day the stripped and mutilated bodies of the soldiers were found by a patrol led by Captain Ten Eyck.

Red Cloud and his men continued to attack soldiers trying to protect the Bozeman Trail. On 2nd August, 1867, several thousand Sioux and Cheyenne attacked a wood-cutting party led by Captain James W. Powell. The soldiers had recently been issued with Springfield rifles and this enabled them to inflict heavy casualties on the warriors. After a battle that lasted four and a half hours, the Native Americans withdrew. Six soldiers died during the fighting and Powell claimed that his men had killed about 60 warriors.

Despite this victory the army was unable to successfully protect the Bozeman Trail and on 4th November, 1868, Red Cloud and 125 chiefs were invited to Fort Laramie to discuss the conflict. As a result of these negotiations the American government withdrew the garrisons protecting the emigrants travelling along the trail to Montana. Red Cloud and his warriors then burnt down the forts.

In December, 1875 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs directed all Sioux bands to enter reservations by the end of January 1876. Sitting Bull, now a medicine man and spiritual leader of his people, refused to leave his hunting grounds. Crazy Horse agreed and led his warriors north to join up with Sitting Bull.

In June 1876 Sitting Bull subjected himself to a sun dance. This ritual included fasting and self-torture. During the sun dance Sitting Bull saw a vision of a large number of white soldiers falling from the sky upside down. As a result of this vision he predicted that his people were about to enjoy a great victory.

On 17th June 1876, General George Crook and about 1,000 troops, supported by 300 Crow and Shoshone, fought against 1,500 members of the Sioux and Cheyenne tribes. The battle at Rosebud Creek lasted for over six hours. This was the first time that Native Americans had united together to fight in such large numbers.

General George A. Custer and 655 men were sent out to locate the villages of the Sioux and Cheyenne involved in the battle at Rosebud Creek. An encampment was discovered on the 25th June. It was estimated that it contained about 10,000 men, women and children. Custer assumed the numbers were much less than that and instead of waiting for the main army under General Alfred Terry to arrive, he decided to attack the encampment straight away.

Custer divided his men into three groups. Captain Frederick Benteen was ordered to explore a range of hills five miles from the village. Major Marcus Reno was to attack the encampment from the upper end whereas Custer decided to strike further downstream.

Reno soon discovered he was outnumbered and retreated to the river. He was later joined by Benteen and his men. Custer continued his attack but was easily defeated by about 4,000 warriors. At the battle of the Little Bighorn Custer and all his 264 men were killed. The soldiers under Reno and Benteen were also attacked and 47 of them were killed before they were rescued by the arrival of General Alfred Terry and his army. It was claimed afterwards that Custer had been killed by his old enemy, Rain in the Face. However, there is no hard evidence to suggest that this is true.

The U.S. army now responded by increasing the number of the soldiers in the area. As a result Sitting Bull and his men fled to Canada, whereas Crazy Horse and his followers surrendered to General George Crook at the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska. Crazy Horse was later killed while being held in custody at Fort Robinson.

Primary Sources

(1) Meriwether Lewis, journal (29th August, 1804)

We had a violent storm of wind and rain last evening; and were engaged during the day in repairing the periogue, and other necessary occupations; when, at four o'clock in the afternoon, sergeant Pryor and his party arrived on the opposite side, attended by five chiefs, and about seventy men and boys. We sent a boat for them, and they joined us, as did also Mr. Durion, the son of our interpreter, who happened to be trading with the Sioux at this time. He returned with sergeant Pryor to the Indians, with a present of tobacco, corn, and a few kettles; and told them that we would speak to their chiefs in the morning. Sergeant Pryor reported, that on reaching their village, which is at twelve miles distance from our camp, he was met by a party with a buffalo robe, on which they desired to carry their visitors: an honour which they declined, informing the Indians that they were not the commanders of the boats: as a great mark of respect, they were then presented with a fat dog, already cooked, of which they partook heartily, and found it well flavoured. The camps of the Sioux are of a conical form, covered with buffalo robes, painted with various figures and colours, with an aperture in the top for the smoke to pass through. The lodges contain from ten to fifteen persons, and the interior arrangement is compact and handsome, each lodge having a place for cooking detached from it.

(2) Meriwether Lewis, journal (26th September, 1804)

We smoked, and he again harangued his people, after which the repast was served up to us. It consisted of the dog which they had just been cooking, this being a great dish among the Sioux, and used on all festivals; to this were added, pemitigon, a dish made of buffalo meat, dried or jerked, and then pounded and mixed raw with grease and a kind of ground potato, dressed like the preparation of Indian corn called hominy, to which it is little inferior. Of all these luxuries which were placed before us in platters with horn spoons, we took the pemitigon and the potato, which we found good, but we could as yet partake but sparingly of the dog. We eat and smoked for an hour, when it became dark: every thing was then cleared away for the dance, a large fire being made in the centre of the house, giving at once light and warmth to the ballroom. The orchestra was composed of about ten men, who played on a sort of tambourin, formed of skin stretched across a hoop; and made a jingling noise with a long stick to which the hoofs of deer and goats were hung; the third instrument was a small skin bag with pebbles in it: these, with five or six young men for the vocal part, made up the band. The women then came forward highly decorated; some with poles in their hands, on which were hung the scalps of their enemies; others with guns, spears or different trophies, taken in war by their husbands, brothers, or connexions. Having arranged themselves in two columns, one on each side of the fire, as soon as the music began they danced towards each other till they met in the centre, when the rattles were shaken, and' they all shouted and returned back to their places. They have no step, but shuffle along the ground; nor does the music appear to be any thing more than a confusion of noises, distinguished only by hard or gentle blows upon the buffalo skin: the song is perfectly extemporaneous. In the pauses of the dance, any man of the company comes forward and recites, in a sort of low guttural tone, some little story or incident, which is either martial or ludicrous; or, as was the case this evening, voluptuous and indecent; this is taken up by the orchestra and the dancers, who repeat it in a higher strain and dance to it. Sometimes they alternate; the orchestra first performing, and when it ceases, the women raise their voices and make a music more agreeable, that is, less intolerable than that of the musicians. The dances of the men, which are always separate from those of the women, are conducted very nearly in the same way, except that the men jump up and down instead of shuffling; and in the war dances the recitations are all of a military cast.

(3) Heinrich Lienhard, From St. Louis to Sutter's Fort, 1846 (1900)

It was not until the day before that we had seen any Indians since leaving Fort Bridger, where there had been some who belonged, I believe, to the Sioux tribe. The ones we saw at that time were poorly clothed, short rather than tall, and were said to belong to the Ute tribe. Where we were now, we were supposed to be in the territory of the so-called Digger Indians, a tribe which has the reputation of being false and cunning, and would not hesitate to murder a white man, if they could do so without fear of punishment. The name Digger is applied to almost all Indians from here to California, because they all live off many roots, which they dig up with pointed sticks. The natives whom we met from here on always called themselves Shoshoni, and this name alone should always be applied to them. We had not seen any wild game for a long time, except occasional traces of them. These traces indicated the presence of bear, elk, and deer; large horns of mountain sheep proved that they too at times frequented this region.

(4) George Ruxton, Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains (1847)

The Sioux are very expert in making their lodges comfortable, taking more pains in their construction than most Indians. They are all of conical form: a framework of straight slender poles, resembling hop-poles, and from twenty to twenty-five feet long, is first erected, round which is stretched a sheeting of buffalo robes, softly dressed, and smoked to render them watertight. The apex, through which the ends of the poles protrude, is left open to allow the smoke to escape. A small opening, sufficient to permit the entrance of a man, is made on one side, over which is hung a door of buffalo hide. A lodge of the common size contains about twelve or fourteen skins, and contains comfortably a family of twelve in number. The fire is made in the centre immediately under the aperture in the roof, and a flap of the upper skins is closed or extended at pleasure, serving as a cowl or chimney-top to regulate the draught and permit the smoke to escape freely. Round the fire, with their feet towards it, the inmates sleep on skins and buffalo rugs, which are rolled up during the day, and stowed at the back of the lodge.

In travelling, the lodge-poles are secured half on each side a horse, and the skins placed on transversal bars near the ends, which trail along the ground - two or three squaws or children mounted on the same horse, or the smallest of the latter borne in the dog travees. A set of lodge-poles will last from three to seven years, unless the village is constantly on the move, when they are soon worn out in trailing over the gravelly prairie. They are usually of ash, which grows on many of the mountain creeks, and regular expeditions are undertaken when a supply is required, either for their own lodges, or for trading with those tribes who inhabit the prairies at a great distance from the locality where the poles are procured.

There are also certain creeks where the Indians resort to lay in a store of kinnik-kinnik (the inner bark of the red willow), which they use as a substitute for tobacco, and which has an aromatic and very pungent flavour. It is prepared for smoking by being scraped in thin curly flakes from the slender saplings, and crisped before the fire, after which it is rubbed between the hands into a form resembling leaf-tobacco, and stored in skin bags for use. It has a highly narcotic effect on those not habituated to its use, and produces a heaviness sometimes approaching stupefaction, altogether different from the soothing effects of tobacco.

(5) George Donner, letter to a friend (27th June, 1846)

We arrived here (Fort Laramie) yesterday without meeting any serious accident. Our company are in good health. Our road has been through a sandy country, but we have as yet had plenty of grass for our cattle and water.... Two hundred and six lodges of Sioux are expected at the Fort today on the way to join the warriors on the war against the Crows. The Indians all speak friendly to us. Two braves breakfasted with us. Their ornaments were tastefully arranged, consisting of beads, feathers, and a fine shell that is got from California, bark variously colored and arranged, and the hair from the scalps they have taken in battle... Our provisions are in good order, and we feel satisfied with our preparations for the trip.

(6) George Catlin, Illustrations of the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians (1848)

On an occasion when I had interrogated a Sioux chief, on the Upper Missouri, about their Government - their punishments and tortures of prisoners, for which I had freely condemned them for the cruelty of the practice, he took occasion when I had got through, to ask me some questions relative to modes in the civilized world, which, with his comments upon them, were nearly as follow; and struck me, as I think they must every one, with great force.

"Among white people, nobody ever take your wife - take your children - take your mother, cut off nose - cut eyes out - burn to death?" No! "Then you no cut off nose - you no cut out eyes - you no burn to death - very good."

He also told me he had often heard that white people hung their criminals by the neck and choked them to death like dogs, and those their own people; to which I answered, "yes." He then told me he had learned that they shut each other up in prisons, where they keep them a great part of their lives because they can't pay money! I replied in the affirmative to this, which occasioned great surprise and excessive laughter, even amongst the women. He told me that he had been to our Fort, at Council Bluffs, where we had a great many warriors and braves, and he saw three of them taken out on the prairie and tied to a post and whipped almost to death, and he had been told that they submit to all this to get a little money, "yes." He said he had been told, that when all the white people were born, their white medicine-men had to stand by and look on - that in the Indian country the women would not allow that - they would be ashamed - that he had been along the Frontier, and a good deal amongst the white people, and he had seen them whip their little children - a thing that is very cruel - he had heard also, from several white medicine-men, that the Great Spirit of the white people was the child of a white woman, and that he was at last put to death by the white people! This seemed to be a thing that he had not been able to comprehend, and he concluded by saying, "the Indians' Great Spirit got no mother - the Indians no kill him, he never die." He put me a chapter of other questions, as to the trespass of the white people on their lands their continual corruption of the morals of their women - and digging open the Indians' graves to get their bones, etc. To all of which I was compelled to reply in the affirmative, and quite glad to close my notebook, and quietly to escape from the throng that had collected around me, and saying (though to myself and silently), that these and an hundred other vices belong to the civilized world, and are practiced upon (but certainly, in no instance, reciprocated by) the "cruel and relentless savage."

(7) Virginia Reed, Across the Plains in the Donner Party (1891)

At Fort Laramie was a party of Sioux, who were on the war path going to fight the Crows or Blackfeet. The Sioux are fine looking Indians and I was not in the least afraid of them. They fell in love with my pony and set about bargaining to buy him. They brought buffalo robes and beautifully tanned buckskin, pretty beaded moccasins, and ropes made of grass, and placing these articles in a heap alongside several of their ponies, they made my father understand by signs that they would give them all for Billy and his rider. Papa smiled and shook his head; then the number of ponies was increased and, as a last tempting inducement, they brought an old coat, that had been worn by some poor soldier, thinking my father could not withstand the brass buttons!

On the sixth of July we were again on the march. The Sioux were several days in passing our caravan, not on account of the length of our train, but because there were so many Sioux. Owing to the fact that our wagons were strung so far apart, they could have massacred our whole party without much loss to themselves. Some of our company became alarmed, and the rifles were cleaned out and loaded, to let the warriors see that we were prepared to fight; but the Sioux never showed any inclination to disturb us... their desire to possess my pony was so strong that at last I had to ride in the wagon, and let one of the drivers take charge of Billy. This I did not like, and in order to see how far back the line of warriors extended, I picked up a large field-glass which hung on a rack, and as I pulled it out with a click, the warriors jumped back, wheeled their ponies and scattered. This pleased me greatly, and I told my mother I could fight the whole Sioux tribe with a spyglass.

(8) Virginia Reed, aged twelve, letter to Mary Keynes (12th July, 1846)

We did not see no Indians from the time we left the cow village till we come to Fort Laramie. The Sioux Indians are going to war with the Crows and we have to pass through their fighting grounds. The Sioux Indians are the prettiest Indians there is. Pa goes buffalo hunting most every day and kills 2 or 3 buffalo every day. Pa shot an elk some of our company saw a grisly bear... We have hard from uncle (Robert Keyes) several times since he went to California and now is gone to Oregon.

(9) Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

With their enemies, they (the Sioux) believed it right to take every advantage. If one of their own tribe committed a serious offense or crime, they believed it right for the victim to administer swift retribution and the whole tribe approved. Among their own tribe and people they had a code of honor which all respected. An Indian could leave his horse, blanket, saddle, or rifle at any place by night or day and it would not be disturbed, though the whole tribe might pass near. This could not be done in any community of white people.

An amusing incident occurred several years ago when Bishop Whipple was sent by the government to hold an important council with the Sioux nation. The Bishop was a most benevolent man and a good friend of the Indians, having sympathy for and influence with them. It was in midwinter, and a great multitude of Indians had gathered in South Dakota to receive this messenger from the Great Father at Washington. Before delivering his address to the Indians the Bishop asked the principal chief if he could rest his fur overcoat in safety. The stalwart warrior, straightening himself up to his full height with dignity, said that he could leave it there with perfect safety, "as there was not a white man within a day's march of the place."

(10) General George Crook, speech to Sioux warriors (October, 1888)

The white men in the East are like birds. They are hatching out their eggs every year, and there is not room enough in the East, and they must go elsewhere; and they come out West, as you have seen them coming for the last few years. And they are still coming, and will come until they overrun all of this country; and you can't prevent it, nor can the President prevent it. Everything is decided in Wash- ington by the majority, and these people come out West and see that the Indians have a big body of land that they are not using, and they say, 'we want the land.'

(11) Chicago Tribune (21st April 1876)

The Sioux ... will most assuredly fight to the bitter end for the country which is their favorite hunting-ground. Of course, the march of civilization cannot be impeded. The white man is destined to drive the aboriginal Indian from his haunts, his hunting-ground, and his lodge. It seems hard that this should be so, but it is the destiny of nations. The scream of the locomotive supplants the war-whoop of the warrior; and the latter, when he hears, knows well its portent. The Plow of the immigrant robs the prairie of its primeval covering, and forces from the rich, willing earth the increase guaranteed by the Great Master to those who by the sweat of their brow seek to earn an honest living; domestic cattle succeed the buffalo, the cackle of the barnyard-fowl the cry of the prairie-hen. There is ample food for moralizing out here, I can tell you.

(12) The Times (7th July, 1876)

So heavy a blow has seldom, indeed, been struck at the regular troops of a civilized Power by a barbarous enemy... It is inevitable that such a disaster should sting the American people almost more as an insult than as an injury; but though the threatened retaliation will be severe, we cannot censure it severely, or contend that it is not dictated by a natural impulse.... We cannot doubt that the recital will kindle a flame in the United States before which the Indians will be driven back upon the alternative of death or deserts more barren and distant even than those of the present "reserves." The people of the United States, and especially the men of the West, who alone in this generation have been brought into actual contact with the Red Indians, have been little under the influence of those humanitarian ideas which are found to plead so powerfully for a mollification of English policy when we have to deal with inferior races. The conduct of the American Government towards the Indians of the Plains has been neither very kindly nor very wise; but its restraining influence, not always implicitly obeyed, has drawn loud complaints from the settlers of the frontier lands.... The borderers will certainly make the disaster to General Custer's command an excuse for forcing upon the Government a war of extermination or of expulsion.

(13) Chicago Tribune (7th July, 1876)

It is time to quit this Sunday-school policy, and let Sheridan recruit regiments of Western pioneer hunters and scouts, and exterminate every Indian who will not remain upon the reservations. The best use to make of an Indian who will not stay on a reservation is to kill him. It is time that the dawdling, maudlin peace-policy was abandoned. The Indian can never be subdued by Quakers, and it is certain that he will never by subdued by such madcap charges as that made by Custer.

(14) John F. Finerty, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

The Sioux never put their dead under ground. This grave was a buffalo hide supported by willow slips and leather thongs, strapped upon four cotton-wood poles about six feet high. The corpse had been removed either by the Indians themselves or by the miners who had passed through a few days before. Around lay two blue blankets with red trimmings, a piece of a jacket all covered with beads, a moccasin, a fragment of Highland tartan, a brilliant shawl and a quantity of horse hair.

(15) New York Times (12th July, 1876)

It is even desirable that our defeats should impel us to wage war in the sharp, vigorous manner which is the truest mercy to friend and foe. But it is neither just nor decent that a Christian nation yield itself to homicidal frenzy, and clamor for the instant extermination of savages by whose unexpected bravery we have been so sadly baffled.

All through the West there is manifested a wild desire for vengeance against the so-called murderers of our soldiers. The press echoes with more or less shamelessness the frontier theory that the only use to which an Indian can be put is to kill him. From all sides come denunciations of what is called in terms of ascending sarcasm "the peace policy," "the Quaker policy," and "the Sunday-school policy." Volunteers are eagerly offering their services "to avenge Custer and exterminate the Sioux," and public opinion, not only in the West, but to some extent in the East, has apparently decided that the Indians have exhausted the forbearance of heaven and earth, and must now be exterminated as though they were so many mad dogs... We must beat the Sioux, but we need not exterminate them.

(16) Nelson Miles, letter to the Secretary of State for War (1890)

The causes that led to the serious disturbance of the peace in the northwest last autumn and winter were so remarkable that an explanation of them is necessary in order to comprehend the seriousness of the situation. The Indians assuming the most threatening attitude of hostility were the Cheyennes and Sioux. Their condition my be stated as follows: For several years following their subjugation in 1877, 1878, and 1879 the most dangerous element of the Cheyennes and the Sioux were under military control. Many of them were disarmed and dismounted; their war ponies were sold and the proceeds returned to them in domestic stock, farming utensils, wagons, etc. Many of the Cheyennes, under the charge of military officers, were located on land in accordance with the laws of Congress, but after they were turned over to civil agents and the vase herds of buffalo and large game had been destroyed their supplies were insufficient, and they were forced to kill cattle belonging to white people to sustain life.

The fact that they had not received sufficient food is admitted by the agents and the officers of the government who have had opportunities of knowing. The majority of the Sioux were under the charge of civil agents, frequently changed and often inexperienced. Many of the tribes became rearmed and remounted. They claimed that the government had not fulfilled its treaties and had failed to make large enough appropriations for their support; that they had suffered for want of food, and the evidence of this is beyond question and sufficient to satisfy any unprejudiced intelligent mind. The statements of officers, inspectors, both of the military and the Interior departments, of agents, of missionaries, ad civilians familiar with their condition, leave no room for reasonable doubt that this was one of the principal causes. While statements may be made as to the amount of money that has been expended by the government to feed the different tribes, the manner of distributing those appropriations will furnish one reason for the deficit.

The unfortunate failure of the crops in the plains country during the years of 1889 and 1890 added to the distress and suffering of the Indians, and it was possible for them to raise but very little from the ground for self-support; in fact, white settlers have been most unfortunate, and their losses have been serious and universal throughout a large section of that country. They have struggled on from year to year; occasionally they would raise good crops, which they were compelled to sell at low prices, while in the season of drought their labor was almost entirely lost. So serious have been their misfortunes that thousands have left that country within the last few years, passing over the mountains to the Pacific slope or returning to the east of the Missouri or the Mississippi.

The Indians, however, could not migrate from one part of the United States to another; neither could they obtain employment as readily as white people, either upon or beyond the Indian reservations. They must remain in comparative idleness and accept the results of the drought-an insufficient supply of food. This created a feeling of discontent even among the loyal and well disposed and added to the feeling of hostility of the element opposed to every process of civilization.

(17) Nelson Miles, telegram to General John Schofield (19th December, 1890)

Replying to your long telegram, one point is of vital importance-the difficult Indian problem can not be solved permanently at this end of the line. It requires the fulfillment by Congress of the treaty obligations which the Indians were entreated and coerced into signing. They signed away a valuable portion of their reservation, and it is now occupied by white people, for which they have received nothing. They understood that ample provision would be made for their support; instead, their supplies have been reduced, and much of the time they have been living on half and two-thirds rations. Their crops, as well as the crops of the white people, for two years have been almost a total failure. The disaffection is widespread, especially among the Sioux, while the Cheyennes have been on the verge of starvation and were forced to commit depredations to sustain life. These facts are beyond question, and the evidence is positive and sustained by thousands of witnesses. Serious difficulty has been gathering for years. Congress has been in session several weeks and could in a single hour confirm the treaties and appropriate the necessary funds for their fulfillment, which their commissioners and the highest officials of the government have guaranteed to these people, and unless the officers of the army can give some positive assurance that the government intends to act in good faith with these people, the loyal element will be diminished and the hostile element increased. If the government will give some positive assurance that it will fulfill its part of the understanding with these 20,000 Sioux Indians, they can safely trust the military authorities to subjugate, control, and govern these turbulent people, and I hope that you will ask the Secretary of War and the Chief Executive to bring this matter directly to the attention of Congress.

(18) John F. Finerty, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

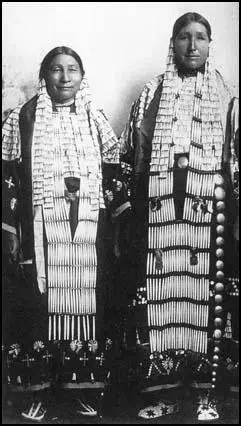

Whether friendly or hostile, the average Indian is a plunderer. He will first steal from his enemy. If he cannot get enough that way, he steals from his friends. While the warriors are fat, tall and good-looking, except in a few cases, the squaws are squatty, yellow, ugly and greasy looking. Hard work disfigures them, for their lazy brutes of sons, husbands and brothers will do no work, and the unfortunate women are used as so many pack mules. Treated with common fairness, the squaws might grow tolerably comely, their figures being generally worse than their faces. It is acknowledged by all that the Sioux women are better treated and handsomer than those of all other tribes. Also they are more virtuous, and the gayest white Adonises confess that the girls of that race seldom yield to the seducer.

(19) Chief Red Cloud in conversation with Father craft, a Catholic missionary (January, 1891)

General Crook came; he, at least, had never lied to us. His words gave the people hope. He died. their hope died again. Despair came again.