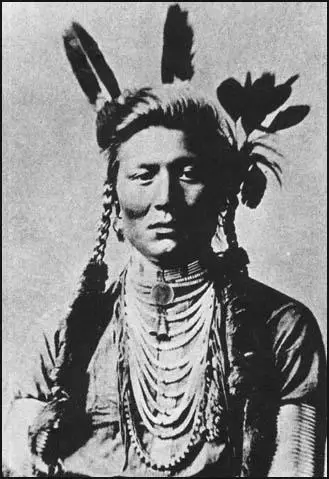

Crow

The Crow tribe originally lived along the Missouri River. They called themselves Absaroke (bird people). In the 18th century the Crow migrated to the area near the Rocky Mountains. The Crow became buffalo hunters. This brought them into conflict with other tribes in the area such as the Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, Pawnee, Sioux, Shoshoni, and the Ute.

The Crow were willing to form an alliance with the United States against their traditional enemies. In 1873Plenty Coups became the chief of the Mountain Crows. He maintained friendly relations with the Americans and supplied scouts for the Sioux Campaign led by General George A. Custer in 1876. His men also took part in the 1877 Nez Perce operation.

In 1883 Plenty Coups went to Washington to discuss the possibility of payments being paid for Crow land. He also managed to bring an end to a brief uprising by Crow warriors in 1887. Plenty Coups became the the principal chief of the Crows in 1904. During the First World War he urged young Crows to join the American armed forces.

Today most Crow live in Montana, near the Little Bighorn. In 1990 there were over 9,000 Crow in the United States.

Primary Sources

(1) George Donner, letter to a friend (27th June, 1846)

We arrived here (Fort Laramie) yesterday without meeting any serious accident. Our company are in good health. Our road has been through a sandy country, but we have as yet had plenty of grass for our cattle and water.... Two hundred and six lodges of Sioux are expected at the Fort today on the way to join the warriors on the war against the Crows. The Indians all speak friendly to us. Two braves breakfasted with us. Their ornaments were tastefully arranged, consisting of beads, feathers, and a fine shell that is got from California, bark variously colored and arranged, and the hair from the scalps they have taken in battle... Our provisions are in good order, and we feel satisfied with our preparations for the trip.

(2) Virginia Reed, Across the Plains in the Donner Party (1891)

At Fort Laramie was a party of Sioux, who were on the war path going to fight the Crows or Blackfeet. The Sioux are fine looking Indians and I was not in the least afraid of them. They fell in love with my pony and set about bargaining to buy him. They brought buffalo robes and beautifully tanned buckskin, pretty beaded moccasins, and ropes made of grass, and placing these articles in a heap alongside several of their ponies, they made my father understand by signs that they would give them all for Billy and his rider. Papa smiled and shook his head; then the number of ponies was increased and, as a last tempting inducement, they brought an old coat, that had been worn by some poor soldier, thinking my father could not withstand the brass buttons!

On the sixth of July we were again on the march. The Sioux were several days in passing our caravan, not on account of the length of our train, but because there were so many Sioux. Owing to the fact that our wagons were strung so far apart, they could have massacred our whole party without much loss to themselves. Some of our company became alarmed, and the rifles were cleaned out and loaded, to let the warriors see that we were prepared to fight; but the Sioux never showed any inclination to disturb us... their desire to possess my pony was so strong that at last I had to ride in the wagon, and let one of the drivers take charge of Billy. This I did not like, and in order to see how far back the line of warriors extended, I picked up a large field-glass which hung on a rack, and as I pulled it out with a click, the warriors jumped back, wheeled their ponies and scattered. This pleased me greatly, and I told my mother I could fight the whole Sioux tribe with a spyglass,

(3) (3)Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

In June, 1878, I decided to make a march up the valley of the Yellowstone to examine a route for a telegraph line and visit the camp of the Crow Indians and the Custer battleground on the Little Big Horn. With a few staff officers and one troop of cavalry as escort, we moved up the valley of the Yellowstone. It was an interesting march. At the mouth of the Big Horn I found the large camp of Crows, some fifteen hundred in number. They had always been on friendly terms with the government and were rich in Indian property. They had splendid lodges made of buffalo and elk hides, with an abundance of Indian paraphernalia. It was estimated that the tribe had at the time twelve thousand horses or Indian ponies. The Crows were ever friends of the white race and bitter enemies of the Sioux, and knowing that the country had been cleared of hostile Sioux, they rejoiced with exceeding joy and hailed us as conquerors of their lifelong enemies. It

took them three days to "paint up"; they adorned themselves and their horses in most gorgeous array.

It was a scene for an artist that can never be reproduced. I have often regretted that Frederic Remington was not with me. Their steeds were painted in most fantastic colors and decorated with spangles, colored horsehair, and hawks' feathers. They seemed as wild as their riders, racing, rearing, and plunging, yet controlled by the most expert horsemanship in the world. The warriors were painted and bedecked in every conceivable way, no two alike. Their war jackets were adorned with elk teeth, silver, mother-of-pearl, beads, and porcupine quills of the richest design and rarest workmanship. Some wore bear-claw necklaces, and human scalplocks dangled from their spears. Their eagle-feathered war bonnets waved in the air, to obtain each one of which required the choice feathers of eight eagles and years of patient and skilled hunting. They passed in review, performed several manceuvers, and finally divided into two bodies and fought the most spirited sham battle I have ever witnessed. The most interesting feature of the whole display was the mimicry of nature by the Indians in war and hunting. Some of the Indians and their ponies were painted so perfectly that it was impossible to distinguish them against a background of green grass, foliage, or sage-brush. This art of making themselves indistinguishable was highly developed among the Indians.

(4) (4)Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

The cause of the Indian War of 1876-77 in the Northwest may be briefly stated. That country originally belonged to the great Crow Tribe of friendly Indians. The Sioux Indians drifted from the region of the Great Lakes, and as they were driven west, in turn, they drove the Crows back to the mountains. The Sioux, or cutthroats, as they were called, finally

took the name of the Dakota Nation, made up principally of Uncapapas, Ogalallas, Minneconjoux, Sans Arcs, and Brules. Also affiliated with them were the Cheyennes, Yanktonais, Tetons, Santees, and Assiniboins. They claimed the whole of that northwest country, what is now North and South Dakota, northern Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, and eastern Montana.

In 1869 the government, in consideration of the Indians giving up a large part of their country, granted them large reservations, known as the Spotted Tail and Red Cloud agencies, and other reservations west of the Missouri. It also allowed them a large range of country as hunting-grounds, and, in addition, agreed to give them stated annuities. It was distinctly understood that the government would keep white people from occupying or trespassing upon the lands granted to the Indians. In the main, the Indians adhered to the conditions of the treaty, but unfortunately the government could not, or did not, comply with its part of the compact. Between the years 1869-75 the pressure of advancing civilization was very great upon all sides. The hunters, prospectors, miners, and settlers were trespassing upon the lands granted to the Indians.

It was generally believed that the Black Hills country possessed rich mineral deposits, and miners were permitted to prospect for mines. Surveying parties were allowed to traverse the country for routes upon which to construct railways, and even the government sent exploring expeditions into the Black Hills country, that reported evidences of gold fields. All this created great excitement on the part of the white people and a strong desire to occupy that country. At the same time it exasperated the Indians to an intense degree, until disaffection developed into open hostilities.

(5) John F. Finerty, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

Their horses - nearly every man had an extra pony - were little beauties, and neighed shrilly at their American brethren, who unused to Indians, kicked, plunged and reared in a manner that threatened a general stampede. "How! How!" the Crows shouted to us, one by one, as they filed past. When near enough, they extended their hands and gave ours a hearty shaking. Most of them were young men, many of whom were handsomer than some white people I have met. Three squaws were there on horseback, wives of the chiefs.

The head sachems were Old Crow, Medicine Crow, Feather Head, and Good Heart, all deadly enemies of the Sioux. Each man wore a gaily colored mantle, handsome leggings, eagle feathers, and elaborately worked moccasins. In addition to their carbines and spears, they carried the primeval bow and arrow. Their hair was long, but gracefully tied up and gorgeously plumed. Their features as a rule were aquiline, and the Crows have the least prominent cheek bones of any Indians that I have yet encountered. The squaws wore a kind of half-petticoat and parted their hair in the middle, the only means of guessing at their sex. Quick as lightning they gained the center of our camp, dismounted, watered and lariated their ponies, constructed their tepees or lodges, and like magic the Indian village arose in our midst. Fires were lighted without delay and the Crows were soon devouring their evening meal of dried bear's meat and black-tailed deer.

(6) Speech made by Old Crow in 1876, quoted by John F. Finerty in his book, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

The great white chief will hear his Indian brother. These are our lands by inheritance. The Great Spirit gave them to our fathers, but the Sioux stole them from us. They hunt upon our mountains. They fish in our streams. They have stolen our horses. They have murdered our squaws, our children. What white man has done these things to us? The face of the Sioux is red, but his heart is black. But the heart of the pale face has ever been red to the Crow.

The scalp of no white man hangs in our lodges. They are thick as grass in the wigwams of the Sioux. The great white chief will lead us against no other tribe of red men. Our war is with the Sioux and only them. We want back our lands. We want their women for our slaves, to work for us as our women have had to work for them. We want their horses for our young men, and their mules for our squaws. The Sioux have trampled upon our hearts. We shall spit upon their scalps. The great white chief sees that my young men have come to fight. No Sioux shall see their backs.Where the white warrior goes there shall we be also.