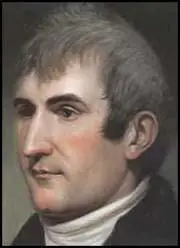

Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis was born in Ivy, Virginia on 18th August, 1774. Lewis received a good education from private tutors. After the death of his father, his mother remarried, and the family moved to Georgia. In 1792 Lewis returned home to manage his mother's estate in Virginia. During this period he became friends with a neighbouring land owner, Thomas Jefferson.

In 1794 Lewis joined the militia and later that year helped put down the Whisky Rebellion. The following year he joined the army and served under William Clark. He took part in the Ohio Indian Campaign that ended with the Battle of Fallen Timbers on 20th August, 1794, in which 107 white people were killed or wounded. Transferred to the 1st Infantry he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant in March 1799.

When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801 he appointed Lewis as his personal secretary. At this time Jefferson read about the adventures of Alexander Mackenzie. In his book, Voyages from Montreal, Mackenzie had described his two expeditions where he had tried to find a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean. For the next few months Jefferson and Lewis discussed the possibility of exploring these unknown lands.

As part of his preparation, Lewis was sent to the University of Pennsylvania to study botany, natural history, medicine, mineralogy and celestial navigation. One of his tutors was Benjamin Rush, who asked Lewis to find out from the Native Americans about their burial customs, diet, medicines, breast feeding, bathing, crime and religious practices.

On 18th January, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson requested permission from Congress to explore the vast lands to the west of the Mississippi. Jefferson claimed that there were "great supplies of fur and peltry" to be obtained from the Native Americans living in this area. He argued that the expedition would provide opportunities for "extending the external commerce of the United States".

The following month Congress approved the venture that became known as the Corps of Discovery. Lewis selected William Clark as his co-commander of the expedition. While the two men prepared for their journey, Jefferson's emissaries in Paris were involved in negotiating the sale of the French possessions in America. In April 1803 the two parties agreed on the terms of the Louisiana Purchase. For the cost of $15 million, the American government purchased 800,000 square miles between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains.

Lewis and Clark assembled a party of 30 men. The group included animal hunters, boatmen, carpenters, soldiers and blacksmiths. They took with them a Native American to serve as an interpreter. The main source of transport was a 60-foot keelboat (barge). Lewis and Clark also spent $669 for presents for those people they met on their journey. This included colored beads, calico shirts, handkerchiefs, mirrors, bells, needles, thimbles, ribbons, kettles and brass curtain rings. They also took dozens of peace medals for the Native Americans. On one side was a picture of Jefferson and on the other side was two hands clasped in friendship.

The expedition began when their keelboat left St. Louis on 14th May 1803. Their main problem during the early weeks was the attacks from gnats and mosquitoes. In his journal Lewis complained that they "infest us in such a manner that we can scarcely exist... they are so numerous that we frequently get them in our throats as we breath".

It was eleven weeks before the party encountered its first Native Americans. The Otos responded well to being given gifts but did not understand the speech made by Lewis that included the following: "The great chief of the seventeen great nations of America, impelled by his parental regard for his newly adopted children on the troubled waters, has sent us out to clear the road. He has commanded his war chiefs to undertake this long journey. You are to live in peace with all the white men, for they are his children; neither wage war against the red men, your neighbours, for they are equally his children and is bound to protect them. "

On 16th August, a member of the party, Moses Read, deserted. He was captured and was punished by being forced "to run the gauntlet four times through the party". A few days later Sergeant Charles Floyd died after suffering from a severe stomach ache.

At the mouth of the Teton River the party made contact with the Sioux. They were unimpressed with the gifts they received and made attempts to stop the party progressing by raising their bows. Lewis responded by ordering the cannons to be aimed at the Sioux warriors. At this the Sioux withdrew and the expedition was allowed to continue.

When the party reached the mouth of the Knife River they decided to make winter camp among the friendly Mandans. The men erected a wooden fort. It was well built and the men were able to survive temperatures of 45 degrees below zero. During the next five months Lewis had to amputate the frostbitten toes of several men in his party. Clark and Lewis also spent time interviewing Mandans about the local terrain. With this information they were able to produce maps that they felt would help them find their way to the Pacific Ocean.

Before they left on their next stage of their journey Clark and Lewis recruited two people living in a neighbouring Minnetaree village. Toussaint Charbonneau, was a French-Canadian, who could speak English and various Native American languages. The other one was Sacajawea, a Shoshoni who had been captured by the Minnetarees when she was about 11 years old and later sold Charbonneau as a slave. Sacajawea, although only 16 years of age was pregnant with Charbonneau's child.

On 7th April, 1805, the Corps of Discovery headed West. A few weeks later Lewis shot a buffalo. Before he had time to reload he was attacked by a bear. Lewis later wrote: "It was an open level plain, not a bush within miles nor a tree within less than three hundred yards. He pitched at me, open mouthed, and full speed, I ran about 80 yards and found he gained on me fast, I then ran into the water the idea struck me to to get into the water to such a depth that I could stand and he would be obliged to swim... he declined to combat on such unequal grounds and retreated."

The Lewis and Clark party saw the Rocky Mountains for the first time on 26th May, 1805. They proceeded up the Missouri they eventually reached the Great Falls. Lewis recorded that the torrent was "300 yards wide and at least 80 feet high". It took the party 24 days to get around the falls. The party was now in Shoshoni territory and Sacajawea began to recognise landmarks and helped guide the party to the Columbia River. She was also able to introduce Lewis and Clark to her brother, Chief Cameahwait. Although reunited with her family, Sacajawea decided to continue with her work as a guide to the Corps of Discovery.

Over the next weeks the party encountered several different tribes including the Nez Perce, Chinooks and Clatsops. On 7th December, 1805, the expedition reached the Pacific Ocean. The men built a fort and remained there until heading east on 23rd March, 1806. The return journey was marred by an attempt by a group of Blackfeet to steal rifles. In the fighting that took place one warrior was killed and another was seriously wounded.

On 23rd September, 1806, the party arrived back at St. Louis. The 28 month expedition produced a considerable body of data concerning the topographical features of the county and its natural resources. They also provided details of animals and birds that lived in the territory they explored.

After visiting President Thomas Jefferson in Washington in 1806 Lewis was appointed Governor of the Louisiana Territory. Lewis was unpopular with the people living in the area and in 1809 he was asked to return to Washington to discuss these problems. On the night of 11th October, 1809, Lewis stayed at a cabin in Tennessee. The next morning he was found dead from gunshot wounds. It was unclear whether he had been murdered or had committed suicide.

Most modern historians accept that Meriwether Lewis committed sucide. However, Xaviant Haze and Paul Schrag, argue in their book, Suppressed History of America: The Murder of Meriwether Lewis and the Mysterious Discoveries of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (2011) that he was murdered.

Primary Sources

(1) Meriwether Lewis, The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1814)

On the acquisition of Louisiana, in the year 1803, the attention of the government of the United States, was early directed towards exploring and improving the new territory. Accordingly in the summer of the same year, an expedition was planned by the president for the purpose of discovering the courses and sources of the Missouri, and the most convenient water communication thence to the Pacific ocean. His private secretary captain Meriwether Lewis, and captain William Clarke, both officers of the army of the United States, were associated in the command of this enterprise. After receiving the requisite instructions, captain Lewis left the seat of government, and being joined by captain Clarke at Louisville, in Kentucky, proceeded to St. Louis, where they arrived in the month of December.

(2) Meriwether Lewis, journal (22nd July, 1804)

The next morning we set sail, and having found at the distance of ten miles from the Platte, a high and shaded situation on the north, we encamped there, intending to make the requisite observations, and to send for the neighbouring tribes, for the purpose of making known the recent change in the government, and the wish of the United States to cultivate their friendship.

(3) Meriwether Lewis, journal (29th August, 1804)

We had a violent storm of wind and rain last evening; and were engaged during the day in repairing the periogue, and other necessary occupations; when, at four o'clock in the afternoon, sergeant Pryor and his party arrived on the opposite side, attended by five chiefs, and about seventy men and boys. We sent a boat for them, and they joined us, as did also Mr. Durion, the son of our interpreter, who happened to be trading with the Sioux at this time. He returned with sergeant Pryor to the Indians, with a present of tobacco, corn, and a few kettles; and told them that we would speak to their chiefs in the morning. Sergeant Pryor reported, that on reaching their village, which is at twelve miles distance from our camp, he was met by a party with a buffalo robe, on which they desired to carry their visitors: an honour which they declined, informing the Indians that they were not the commanders of the boats: as a great mark of respect, they were then presented with a fat dog, already cooked, of which they partook heartily, and found it well flavoured. The camps of the Sioux are of a conical form, covered with buffalo robes, painted with various figures and colours, with an aperture in the top for the smoke to pass through. The lodges contain from ten to fifteen persons, and the interior arrangement is compact and handsome, each lodge having a place for cooking detached from it.

(4) Meriwether Lewis, journal (30th August, 1804)

The fog was so thick that we could not see the Indian camp on the opposite side, but it cleared off about eight o'clock. We prepared a speech, and some presents, and then sent for the chiefs and warriors, whom we received, at twelve o'clock, under a large oak tree, near to which the flag of the United States was flying. Captain Lewis delivered a speech, with the usual advice and counsel for their future conduct. We then acknowledged their chiefs, by giving to the grand chief a flag, a medal, a certificate, with a string of wampum; to which we added a chief's coat; that is, a richly laced uniform of the United States artillery corps, and a cocked hat and red feather. One second chief and three inferior ones were made or recognized by medals, and a suitable present of tobacco, and articles of clothing. We then smoked the pipe of peace, and the chiefs retired to a bower, formed of bushes, by their young men, where they divided among each other the presents, and smoked and eat, and held a council on the answer which they were to make us tomorrow. The young people exercised their bows and arrows in shooting at marks for heads, which we distributed to the best marksmen; and in the evening the whole party danced until a late hour, and in the course of their amusement we threw among them some knives, tobacco, bells, tape, and binding, with which they were much pleased. Their musical instruments were the drum, and a sort of little bag made of buffalo hide, dressed white, with small shot or pebbles in it, and a bunch of hair tied to it. This produces a sort of rattling music, with which the party was annoyed by four musicians during the council this morning.

(5) Meriwether Lewis, journal (26th September, 1804)

We smoked, and he again harangued his people, after which the repast was served up to us. It consisted of the dog which they had just been cooking, this being a great dish among the Sioux, and used on all festivals; to this were added, pemitigon, a dish made of buffalo meat, dried or jerked, and then pounded and mixed raw with grease and a kind of ground potato, dressed like the preparation of Indian corn called hominy, to which it is little inferior. Of all these luxuries which were placed before us in platters with horn spoons, we took the pemitigon and the potato, which we found good, but we could as yet partake but sparingly of the dog. We eat and smoked for an hour, when it became dark: every thing was then cleared away for the dance, a large fire being made in the centre of the house, giving at once light and warmth to the ballroom. The orchestra was composed of about ten men, who played on a sort of tambourin, formed of skin stretched across a hoop; and made a jingling noise with a long stick to which the hoofs of deer and goats were hung; the third instrument was a small skin bag with pebbles in it: these, with five or six young men for the vocal part, made up the band. The women then came forward highly decorated; some with poles in their hands, on which were hung the scalps of their enemies; others with guns, spears or different trophies, taken in war by their husbands, brothers, or connexions. Having arranged themselves in two columns, one on each side of the fire, as soon as the music began they danced towards each other till they met in the centre, when the rattles were shaken, and' they all shouted and returned back to their places. They have no step, but shuffle along the ground; nor does the music appear to be any thing more than a confusion of noises, distinguished only by hard or gentle blows upon the buffalo skin: the song is perfectly extemporaneous. In the pauses of the dance, any man of the company comes forward and recites, in a sort of low guttural tone, some little story or incident, which is either martial or ludicrous; or, as was the case this evening, voluptuous and indecent; this is taken up by the orchestra and the dancers, who repeat it in a higher strain and dance to it. Sometimes they alternate; the orchestra first performing, and when it ceases, the women raise their voices and make a music more agreeable, that is, less intolerable than that of the musicians. The dances of the men, which are always separate from those of the women, are conducted very nearly in the same way, except that the men jump up and down instead of shuffling; and in the war dances the recitations are all of a military cast.

(6) Meriwether Lewis, journal (26th October, 1804)

Among others who visited us was the son of the grand chief of the Mandans, who had his two little fingers cut off at the second joints. On inquiring into this accident, we found that it was customary to express grief for the death of relations by some corporeal suffering, and that the usual mode was to lose two joints of the little fingers, or sometimes the other fingers. The wind blew very cold in the evening from the southwest. Two of the party are affected with rheumatic complaints.

(7) Meriwether Lewis, journal (15th February, 1805)

In the course of the day one of the Mandan chiefs returned from captain Lewis's party, his eyesight having become so bad that he could not proceed. At this season of the year the reflection from the ice and snow is so intense as to occasion almost total blindness. This complaint is very common, and the general remedy is to sweat the part affected by holding the face over a hot stone, and receiving the fumes from snow thrown on it.

(8) Meriwether Lewis, journal (7th April, 1805)

The party now consisted of thirty-two persons. Besides ourselves were sergeants John Ordway, Nathaniel Pryor, and Patrick Gass: the privates were William Bratton, John Colter, John Collins, Peter Cruzatte, Robert Frazier, Reuben Fields, Joseph Fields, George Gibson, Silas Goodrich, Hugh Hall, Thomas P. Howard, Baptiste Lepage, Francis Labiche, Hugh M'Neal, John Potts, John Shields, George Shannon, John B. Thompson, William Werner, Alexander Willard, Richard Windsor, Joseph Whitehouse, Peter Wiser, and captain Clarke's black servant York. The two interpreters, were George Drewyer and Tousaint Chaboneau. The wife of Chaboneau also accompanied us with her young child, and we hope may be useful as an interpreter among the Snake Indians. She was herself one of that tribe, but having been taken in war by the Minnetarees, by whom she was sold as a slave to Chaboneau, who brought her up and afterwards married her.

(9) Meriwether Lewis, journal (17th July, 1805)

These mountains have their sides and summits partially varied with little copses of pine, cedar, and balsam fir. A mile and a half beyond this creek the rocks approach the river on both sides, forming a most sublime and extraordinary spectacle. For five and three quarter miles these rocks rise perpendicularly from the water's edge to the height of nearly twelve hundred feet. They are composed of a black granite near its base, but from its lighter colour above and from the fragments we suppose the upper part to be flint of a yellowish brown and cream colour. Nothing can be imagined more tremendous than the frowning darkness of these rocks, which project over the river and menace us with destruction. The river, of one hundred and fifty yards in width, seems to have forced its channel down this solid mass, but so reluctantly has it given way that during the whole distance the water is very deep even at the edges, and for the first three miles there is not a spot except one of a few yards, in which a man could stand between the water and the towering perpendicular of the mountain: the convulsion of the passage must have been terrible, since at its outlet there are vast columns of rock torn from the mountain which are strewed on both sides of the river, the trophies as it were of the victory. Several fine springs burst out from the chasms of the rock, and contribute to increase the river, which has now a strong current, but very fortunately we are able to overcome it with our oars, since it would be impossible to use either the cord or the pole.

(10) Meriwether Lewis, letter to Thomas Jefferson (23rd September, 1806)

The Missouri and all it's branches from the Cheyenne upwards abound more in beaver and otter, than any other streams on earth, particularly that proportion of them lying within the Rocky Mountains. The furs of all this immense tract of country including such as may be collected on the upper portion of the River St. Peters, Red river and the Assinniboin with the immense country watered by the Columbia, may be conveyed to the mouth of the Columbia by the 1st of August in each year and from thence be shipped to, and arrive in Canton earlier than the furs at present shipped from Montreal annually arrive in London. The British N. West Company of Canada were they permitted by the United States might also convey their furs collected in the Athabaske, on the Saskashawan, and South and West of Lake Winnipeg by that rout within the period before mentioned. Thus the productions of nine tenths of the most valuable fur country of America could be conveyed by the rout proposed to the East Indies.

(11) Chief Joseph, An Indian's Views of Indian Affairs, North American Review (April, 1879)

My friends, I have been asked to show you my heart. I am glad to have a chance to do so. I want the white people to understand my people. Some of you think an Indian is like a wild animal. This is a great mistake. I will tell you all about our people, and then you can judge whether an Indian is a man or not. I believe much trouble and blood would be saved if we opened our hearts more. I will tell you in my way how the Indian sees things. The white man has more words to tell you how they look to him, but it does not require many words to speak the truth. What I have to say will come from my heart, and I will speak with a straight tongue. Ah-cum-kin-i-ma-me-hut (the Great Spirit) is looking at me, and will hear me.

My name is In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat (Thunder traveling over the Mountains). I am chief of the Wal-lam-wat-kin band of Chute-pa-lu, or Nez Perces (nose-pierced Indians). I was born in eastern Oregon, thirty-eight winters ago. My father was chief before me. When a young man, he was called Joseph by Mr. Spaulding, a missionary. He died a few years ago. There was no stain on his hands of the blood of a white man. He left a good name on the earth. He advised me well for my people.

Our fathers gave us many laws, which they had learned from their fathers. These laws were good. They told us to treat all men as they treated us; that we should never be the first to break a bargain; that it was a disgrace to tell a lie; that we should speak only the truth; that it was a shame for one man to take from another his wife, or his property without paying for it. We were taught to believe that the Great Spirit sees and hears everything, and that he never forgets; that hereafter he will give every man a spirit-home according to his deserts: if he has been a good man, he will have a good home; if he has been a bad man, he will have a bad home. This I believe, and all my people believe the same.

The first white men of your people who came to our country were named Lewis and Clarke. They also brought many things that our people had never seen. They talked straight, and our people gave them a great feast, as a proof that their hearts were friendly. These men were very kind. They made presents to our chiefs and our people made presents to them. We had a great many horses, of which we gave them what they needed, and they gave us guns and tobacco in return. All the Nez Perces made friends with Lewis and Clarke, and agreed to let them pass through their country, and never to make war on white men. This promise the Nez Perces have never broken.