On this day on 27th March

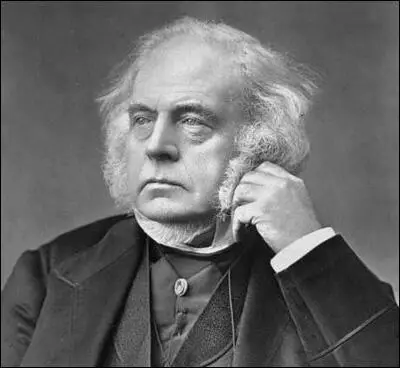

On this day in 1814 Charles Mackay, the son of a navy lieutenant was born in Scotland in 1814. His mother died when he was young and so he was brought up by foster parents.

At the age of sixteen he was employed as the private secretary to William Cockerill, an ironmaster based in Belgium. In his spare-time he wrote articles for the local newspaper.

Mackay returned to Britain in 1832 and for the next three years contributed to several newspapers. In 1835 he obtained his first permanent post in journalism when he was appointed as an assistant to George Hogarth, the sub-editor of the Morning Chronicle. Other journalists working for the newspaper at the time included Charles Dickens and William Hazlitt. Mackay eventually was promoted to the post of assistant editor.

In 1844 Mackay left the Morning Chronicle and became editor of the Glasgow Argus. While in Scotland he also contributed articles and poetry to the Daily News, a newspaper established by Charles Dickens in 1846. After four years in Glasgow, Mackay returned to London and joined the staff of the London Illustrated News the successful journal owned by Herbert Ingram.

In 1849 Henry Mayhew suggested to John Douglas Cook, the editor of the Morning Chronicle, that the newspaper should carry out an investigation into the condition of the labouring classes in England and Wales. Cook agreed and recruited Mackay, Angus Reach and Shirley Brooks to help Mayhew collect the material. Mackay was given the task of surveying the situation in Liverpool and Birmingham.

Mackay's poetry was collected together until the title Voices from the Crowd. Some of them were set to music by his friend Henry Russell. These were very successful and one songsheet, The Good Time Coming, sold over 400,000 copies. Mackay published his two volume autobiography, Forty Years Recollections and Through the Long Day two years before his death in 1889.

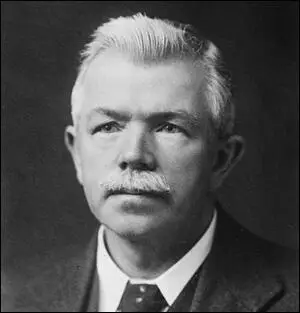

On this day in 1869 trade union organizer John Robert Clynes, one of seven children of Patrick Clynes, an illiterate Irish farmworker, and his wife, Bridget Scanlan, was born in Oldham. His father had been evicted in 1851 and emigrated to Lancashire, where he gained employment as a gravedigger.

Clynes began work as a piecer at the local cotton mill when he was ten years old. He later recalled: "I remember no golden summers, no triumphs at games and sports, no tramps through dark woods or over shadow-racing hills. Only meals at which there never seemed to be enough food, dreary journeys through smoke-fouled streets, in mornings when I nodded with tiredness and in evenings when my legs trembled under me from exhaustion."

James Smith Middleton has pointed out: "Out of his early wages he bought a tattered dictionary for 6d. and Cobbett's Grammar for 8d. He received 3d. a week for reading regularly to three blind men, whose discussions of the political news aroused his interest. He paid 8d. for tuition on two nights a week from a former schoolmaster."At the age of sixteen, Clynes wrote a series of anonymous articles about life in a cotton mill. The articles illustrated the harsh way children were still being treated in textile factories. Clynes argued that the Spinners Union was not doing enough to protect child workers and in 1886 he helped form the Piercers' Union.

In 1892 Will Thorne recruited Clynes as organiser of the Lancashire Gasworkers' Union. Clynes joined the Fabian Society where he met George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter and Sidney Webb. He also joined the Independent Labour Party and was one of the delegates at the conference in February, 1900 that established the Labour Representation Committee. A few months later Clynes was elected as one of the Trade Union representatives on the LRC executive.

Clynes was a talented writer and in the early 1900s became a regular contributor to socialist newspapers such as The Clarion. Clynes, the Secretary of Oldham's Trade Council, was asked to be the Labour Party candidate for North East Manchester in the 1906 General Election. Clynes won the seat soon established himself as one of the leaders of the party in Parliament. Like George Lansbury and Philip Snowden, Clynes was a strong supporter of votes for women.

A popular and well-respected member of the House of Commons, Clynes was elected as vice-chairman of the Labour Party in 1910. Ramsay MacDonald, the chairman of the party, was totally against Britain's involvement in the First World War. His views were shared by other senior figures such as James Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Others in the party such as Clynes, Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort.

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. Ramsay MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship. He wrote in his diary: "I saw it was no use remaining as the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result. The Chairmanship was impossible. The men were not working, were not pulling together, there was enough jealously to spoil good feeling. The Party was no party in reality. It was sad, but glad to get out of harness." Arthur Henderson, once again, became the leader of the party.

In May 1915, Henderson became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. Bruce Glasier commented in his diary: "This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour." Clynes initially opposed the entry of Labour into the Herbert Asquith coalition. However, he continued to support the war effort and in July 1917 the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, rewarded Clynes by appointing him as Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Food in his coalition government.

William Adamson replaced Arthur Henderson as chairman of the party in October 1917. In the 1918 General Election, a large number of the Labour leaders lost their seats. This included Henderson, Ramsay MacDonald, Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett. Adamson held the post until February 1921 when he was replaced by Clynes. Snowden commented: "Clynes had considerable qualifications for Parliamentary leadership. He was an exceptionally able speaker, a keen and incisive debater, had wide experience of industrial questions, and a good knowledge of general political issues. In the Labour Party Conferences when the platform got into difficulties with the delegates, Mr. Clynes was usually put up to calm the storm."

Clynes was strongly opposed to working with the Communist Party of Great Britain: "In countries where no democratic weapon exists a class struggle for the enthronement of force by one class over other classes may be condoned, but in this country where the wage-earners possess 90 per cent of the voting power of the country agitation to use not the power which is possessed but some risky class dictatorship is a futile and dangerous doctrine."

In the 1922 General Election the Labour Party won 142 seats, making it the second largest political group in the House of Commons after the Conservative Party (347). David Marquand has pointed out that: "The new parliamentary Labour Party was a very different body from the old one. In 1918, 48 Labour M.P.s had been sponsored by trade unions, and only three by the ILP. Now about 100 members belonged to the ILP, while 32 had actually been sponsored by it, as against 85 who had been sponsored by trade unions.... In Parliament, it could present itself for the first time as the movement of opinion rather than of class."

At a meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party on 21st November, 1922, Emanuel Shinwell proposed Ramsay MacDonald should become chairman. David Kirkwood, a fellow Labour MP, commented: "Nature had dealt unevenly with them. She had endowed MacDonald with a magnificent presence, a full resonant voice, and a splendid dignity. Clynes was small, unassuming, of uneven features, and voice without colour." After much discussion, Clynes received 56 votes to MacDonald's 61. Clynes, with characteristic generosity, declared that the whole party was determined to support the new leader.

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservatives had 258, MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. As MacDonald had to reply on the support of the Liberal Party, he was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. Clynes was appointed lord privy seal and deputy leader of the House of Commons.

When MacDonald became Prime Minister again after the 1929 General Election, he appointed Joseph Clynes as his Home Secretary. Clynes was active in the area of prison reform and also ordered an inquiry into the cotton trade. However, he caused some controversy when he refused permission for Leon Trotsky to settle in England. As James Smith Middleton has pointed out: "In 1931 Clynes introduced an electoral reform bill providing for the alternative vote, and also abolishing university representation, a clause which was deleted by four votes in the committee stage in the House of Commons."

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority, including Clynes, George Lansbury and Arthur Henderson voted against the measures suggested by the May Committee.

Ramsay MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

In October, MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Clynes lost his seat at North East Manchester. He now devoted himself to the work of his union, the National Union of General and Municipal Workers, it covered nearly half a million members in a wide range of industries.

Clynes returned to the House of Commons at the 1935 General Election. Now sixty-years old he was considered an elder statesman of the labour movement. In 1945 he retired on reaching the parliamentary age limit set by his union and lived quietly on the pension which it gave him, in his Putney home. In 1947 he complained to The Times about his insufficient pension" and a fund was raised by his former parliamentary colleagues.

John Robert Clynes died at his home, 41 St John's Avenue, Putney Hill, on 23rd October, 1949.

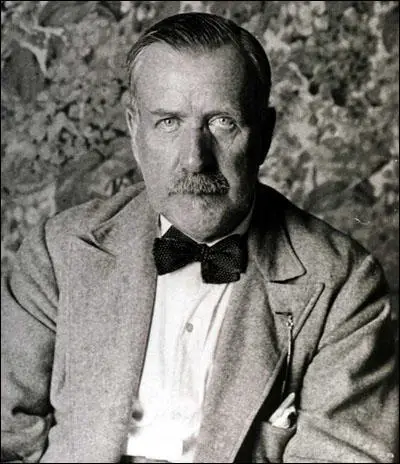

On this day in 1871 Heinrich Mann, the oldest child of Thomas Johann Mann and Júlia da Silva Bruhns, was born in Lübeck. His father was an energetic and successful businessman. In 1863, at the age of 23, had inherited the ownership of the Johann Siegmund Mann firm, a granary and shipping business dating back to the previous century. Heinrich remembered his father as "young, gay, and carefree."

Heinrich's brother, Thomas Mann, later recalled his father's "dignity and good sense, his ambition and industry, his personal and intellectual distinction, his social talents and his humor... he was not robust, rather nervous and susceptible to suffering; but he was a man dedicated to self-control". His mother was described as "a much admired beauty and extraordinarily musical".

Thomas Johann Mann was often in conflict with his son who he described as having a "dreamy loss of self-control and lack of consideration for others". He hated school and although he spent most of his time reading he refused to conform to the requirements of his teachers. He still passed his exams with high grades but refused to go to university.

Heinrich Mann refused to join the family business and in October 1889, he was employed by the Dresden book shop of Jaensch & Zahn as an apprentice. His employer was not impressed with his new apprentice and accused him of being "apathetic, indolence and truculence".

In 1890 Heinrich Mann had some of poems published in Die Gesellschaft, the magazine was regarded to most modernist of the German periodicals. The following year Heinrich Mann moved to Berlin with the ambition to be a successful novelist. His father was very angry with this development and wrote: "I wish the guardians of my children to consider it their duty to influence these children towards a practical education. Insofar as they are able, they are to oppose my eldest son's leanings towards so-called literary activity. In my opinion he lacks the prerequisites for sound, successful work in this direction, namely sufficient study and broad knowledge."

Heinrich Mann inherited some money from his father's estate in 1891 that enabled him to concentrate on being a writer. His hero was Heinrich Heine. His younger brother, Thomas Mann, also attempted to make it as a writer. He also admired Heine: "In his enthusiasm for Heine, in trying his hand at verse, fiction, and criticism, Thomas at this time was faithfully following in the footsteps of his elder brother. His youthful revolt against society, natural though it was for his age, seems also to have been borrowed from his brother, who was bohemian by instinct".

Heinrich's first novel, Within a Family, was published in 1893. He was unable to obtain a living as a novelist and in April 1895 he became the editor of a periodical, The Twentieth Century: A Journal of German Art and Welfare. It was anti-capitalist and frequently anti-Semitic: "Heinrich drew caricatures of wealthy Jews and intellectuals, and he attacked the power of the Jewish press."

In 1896 he moved to Paris and wrote what became known as "My Plan". Richard Winston has argued: "It is a curious document, full of delighted anticipations, avowals to himself that the whole plan is in the interests of a literary project, propitiatory reassurances to the ghost of his father that he really is not a wastrel. Heinrich also wondered whether he would be seeing the authentic fashionable world."

Heinrich Mann's first important novel was In the Land of Cockaigne (1900) a portrayal of the decadence of high society. It is considered by most critics to be inferior to his brother's first novel, Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family (1901), a fictional account of the Mann family. "Compared to the Tolstoyan achievement of Buddenbrooks, Heinrich's novel may seem comparatively light, but contemporaries like Rilke felt it had ushered both expressionism and social criticism into the German novel. For his admirers Heinrich's early work, more topical, vivacious, and unfinished than his brother's - as the journalistic rate of production might guarantee - provides a more useful guide to the era as well as prophetic views of Germany's future. (These readers would contend that Buddenbrooks points backward.)

In January 1905, Thomas Mann decided to marry Katia Pringsheim Mann, the daughter of a wealthy, Jewish industrialist family who owned coal mines and early railroads. Thomas wrote to Heinrich about his decision: "A feeling of the lack of freedom that I cannot rid myself of up to now, and of course you call me a timid plebeian. But it's easy for you to talk. You are absolute. I, on the other hand, have paused to improve my state of mind."

Heinrich Mann did not attend his brother's wedding. His mother, who also did not approve of the marriage, wrote, "Please, please, dear Heinrich, follow my advice and do not withdraw from Tommy... You are both men blessed by God, dear Heinrich - don't let your personal relationship with Tommy become strained.... Your latest works were not without exception liked. That has nothing to do with your sibling relationship."

Mann's portrait of a tyrannical provincial schoolmaster, Professor Unrat (1905) gained him good reviews. However, it was his novels, The Poor (1917), Man of Straw (1918) and The Patrioteer (1918), that brought him "great fame, a prophetic image, large earnings". Thomas was jealous of Heinrich's success: "My brother-problem is the real, in any case the most difficult, problem of my life... At every step kinship and affront.... his books are bad in such an extraordinary way as to provoke passionate antagonism".

Heinrich Mann became increasingly interested in left-wing politics. He was a supporter of Kurt Eisner, the Jewish leader of the Independent Socialist Party in Munich. This was a departure from his earlier anti-Semitism. Konrad Heiden has pointed out: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds."

The following day Eisner led a large crowd into the local parliament building, where he made a speech where he declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. Eisner explained that his program would be based on democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a republic.

On 9th November, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II also abdicated and the Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy and was keen for one of the his grandsons to replace Wilhelm.

On 21st February, 1919, Eisner was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the Independent Socialist Party he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land."

Heinrich Mann spoke at Eisner's funeral and at his memorial three weeks later. Thomas Mann, who was deeply opposed to socialism, commented that Heinrich claimed that "Eisner had been the first intellectual at the head of a German state... in a hundred days he had had more creative ideas than others in fifty years, and... had fallen as a martyr to truth. Nauseating!"

In 1924 Thomas Mann published his most successful novel, The Magic Mountain. This was followed by Disorder and Early Sorrow (1925). Heinrich wrote: "You know as well as I do myself that your honours and successes do not bother me. Sometimes a few crumbs are even tossed my way." Mann success was emphasized by being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929.

Heinrich Mann had more success when his novel, Professor Unrat, was turned into the popular film, The Blue Angel (1930). The film was directed by Josef von Sternberg and starred Emil Jannings, Marlene Dietrich and Kurt Gerron. Philip French has argued: "Jannings gives an exquisitely detailed performance as the pompous, middle-aged Professor Rath, a high-school teacher whose life is destroyed through his romantic infatuation with Lola Lola (Dietrich), a wilful young singer he meets at the eponymous nightclub."

Heinrich fell in love with the actress Trude Hesterberg, a Berlin actress. He now divorced his first wife Mimi Kanova, a Czech actress, (married 1914). However, the couple argued about politics and when she joined the Nazi Party, the relationship came to an end: "As a woman and an artist I naturally have been influenced by all tendencies of the times, but I never became a politician. I have always instinctively considered my art as a megaphone of the popular opinions of the day. Out of this sense of artistic duty, I became a member of the Nazi party and the Fighting League."

In June 1932 Heinrich Mann joined with Albert Einstein, Ernst Toller, Arnold Zweig, Käthe Kollwitz, Karl Kollwitz, Willi Eichler, Arthur Kronfeld, Kurt Grossmann, Karl Emonts, Anton Erkelenz, Hellmuth Falkenfeld, Walter Hammer, Theodor Hartwig, Maria Hodann, Minna Specht, Hanns-Erich Kaminski, Erich Kaestner, Theodor Plievier, August Siemsen, Helene Stocker, Pietro Nenni, Erich Zeigner, Paul Oestreich and Franz Oppenheimer to sign an appeal by the International Socialist Combat League (ISK) for tactical cooperation of German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the Reichstag elections of July 1932.

Adolf Hitler gained power in January 1933. Soon afterwards, a large number of writers were declared to be "degenerate authors" because they were Jews or held left-wing views. This included Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Hans Eisler, Ernst Toller, Albert Einstein, Helen Keller, H.G. Wells, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Erich Maria Remarque, Karl Kautsky, Thomas Heine, Arnold Zweig, Ludwig Renn, Jack London, Rainer Maria Rilke, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Franz Kafka, Theodor Plievier, Magnus Hirschfeld, Max Brod, Richard Katz, Franz Werfel, Alfred Döblin, Lion Feuchtwangerand Hermann Hesse. On 10th May, the Nazi Party arranged the burning of thousands of "degenerate literary works" were burnt in German cities.

However, Thomas Mann's work still remained popular in Germany and unlike his brother, Heinrich, had made no statements attacking the regime. His biographer, Hermann Kurzke, has argued that during the period before he took power, Mann developed friendships with some significant figures in the Nazi Party: "Does that make Thomas Mann a precursor of Fascism? He certainly made an effort to stay out of the way of the resurgent right-wing movement of the time. Very early on in the summer of 1921, he took note of the rising Nazi movement and dismissed it as ‘swastika nonsense’. As early as 1925 when Hitler was still imprisoned in Landsberg, he rejected the cultural barbarity of German Fascism with an extensive, decisive and clearly visible gesture." However, others had pointed out, he had always been careful not to attack Hitler in print.

To escape arrest, Heinrich Mann, went to live in Paris. He joined Klaus Mann and Erika Mann in the German resistance to Hitler. Klaus went to Amsterdam, where he worked for the first emigre journal of anti-fascism, Die Sammlung, which attacked the government in Nazi Germany. Heinrich contributed to the magazine. Thomas Mann condemned the venture and pleaded with his son and brother to withdraw their support for the journal.

In 1939 Heinrich Mann married Nelly Kroeger, who he had been living with for ten years. She was almost thirty years his junior and described as "a pretty, animated, ex-barmaid". After the fall of France in the summer of 1940, Heinrich and Nelly escaped across the Pyrenees to reach Madrid. Heinrich, who was now 69, needed the support of the much younger Nelly. Eventually they got to Lisbon and took the last available ship passages to New York City.

Heinrich Mann went to live in Los Angeles and was given a 12 month contract with Warner Brothers (none of the movies were made). After this he became more and more impoverished. He received help from his brother Thomas but he had a intense dislike of Nelly who was frequently drunk, who he described as "repugnant... foolish ... a terrible trollop".

In January, 1944, they made a joint suicide attempt. Nelly was transferred to a psychiatric hospital. She told Heinrich: "I can not think of what I have suffered the last two years, and only because I in my deepest humiliation a glass of wine much had been drinking and was often drunk, I have not completely lost my mind. Now I want to live! It's all up to you, that we organize in quality and without making even more attention this matter. Otherwise you force me to do something that you intended... sorry."

Nelly Mann returned home but took an overdose of sleeping pills on 17th December, 1944. Heinrich Mann reported in a letter to a friend "She died in the ambulance... This last year was misery and terror... people who know nothing, I try to suggest that it is better... No... I hardly leave the apartment, which her was." Heinrich was devastated but Thomas Mann was "relieved". Thomas wrote that Heinrich's "very favorable income had melted away far into the negative through the disastrous goings-on of his wife."

Heinrich Mann remained active in left-wing politics but was upset when friends such as Hans Eisler and Bertolt Brecht were ordered to appear before the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Eisler and Brecht both decided to leave the country. Thomas Mann described the behaviour of members of the HUAC such as John Rankin and J. Parnell Thomas as "fascistic". In his diary he wrote: "What oath would Congressman Rankin or Thomas take if forced to swear that they hated fascism as much as Communism?"

The East German government offered him the post as president of the Academy of Fine Arts. Thomas commented in his diary that "Soviet money reaches Heinrich, which he claims is royalties, while it is probably travel money."Heinrich Mann was making plans to leave the country when he died in Los Angeles on 11th March, 1950.

Heinrich Mann was buried in Santa Monica: "The participants not very numerous. Wreaths and flowers a beautiful sight. My wreath with To my big brother, with love."

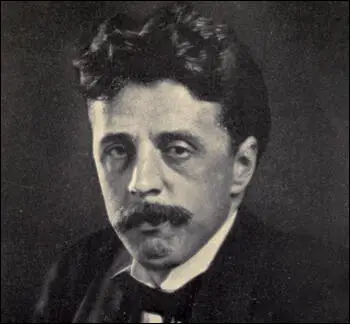

Heinrich Mann (c. 1930)

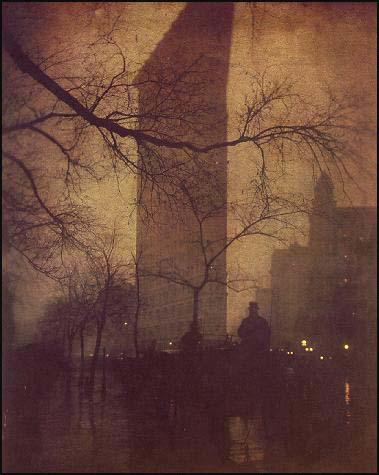

On this day in 1879 photographer Edward Steichen was born in Luxembourg on 27th March, 1879. When Edward was three years old his family moved to the United States and eventually settled in Hancock, Michigan

At the age of fifteen Steichen began a lithography apprenticeship with the American Fine Art Company in Milwaukee. He also attended lectures by Richard Lorenz and Robert Schode at Milwaukee's Arts Students League. Steichen took up photography in 1895 but continued to paint for the next twenty years.

In 1899 some of Steichen's photographs were exhibited at the Second Philadelphia Salon. Three of these prints were purchased by the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The two men became close friends and in 1902 joined with Clarence White, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Gertrude Kasebier to form the Photosecession Group. Stieglitz also promoted Steichen's work in his journal, Camera Work and his Little Gallery on Fifth Avenue, New York.

Steichen began experimenting with colour photography in 1904 and was one of the first people in the United States to use the Lumiere Autochrome process. He travelled to Europe and collected the work of the best photographers and these were exhibited by Alfred Stieglitz in 1910 at the International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography. Thirty-one of Steichen's photographs also appeared in the exhibition.

In 1913 Alfred Stieglitz devoted a double issue of Camera Work to Steichen's photographs. He wrote in the magazine: "Nothing I have ever done has given me quite so much satisfaction as finally sending this number out into the world."

During the First World War Steichen became commander of the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces. This gave him the opportunity to become involved with aerial photography. Shocked by what he witnessed on the Western Front, Steichen denounced impressionistic photography and instead concentrated on realism. He later wrote: "I am no longer concerned with photography as an art form. I believe it is potentially the best medium for explaining man to himself and his fellow man."

After the war Steichen became increasingly involved in commercial photography. He worked for the J. Walter Thompson Advertising Agency and in 1923 became chief photographer for Conde Nast Publications and his work appeared regularly in Vogue and Vanity Fair. He also published portraits of many well-known figures including Carl Sandburg, Charles Chaplin and H. L. Mencken.

In 1945 Steichen became Director of the U.S. Naval Photographic Institute. Steichen was responsible for the publication of the navy's combat photography and during the Second World War organized the Road to Victory and Power in the Pacific exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

After the war Steichen became director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art. This included the organization in 1955 of what became the most popular exhibition in the history of photography, The Family of Man. In 1964 the Edward Steichen Photography Center was established in the museum. Edward Steichen died in West Redding, Connecticut, on 25th March, 1973.

On this day in 1886 Sergey Kirov was born. Sergei Kirov was born in Urzhum, Russia. His parents died when he was young and he was brought up by his grandmother until he was seven when he was sent to an orphanage.

In 1901 he attended the Kazan Technical School. During this period he became a Marxist and joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1904. He took part in the 1905 Revolution in St. Petersburg. He was arrested but was released after three months in prison. Kirov now joined the Bolshevik faction of the SDP. He lived in Tomsk where he was involved in the printing of revolutionary literature. He also helped to organize a successful strike of railway workers.

In 1906 Kirov moved to Moscow but he was soon arrested for printing illegal literature. Several of his comrades were executed but he was sentenced to three years in prison. Kirov later wrote: "The prison library was quite satisfactory, and in addition one was able to receive all the legal writings of the time. The only hindrances to study were the savage sentences of courts as a result of which tens of people were hanged. On many a night the solitary block of the Tomsk country prison echoed with condemned men shouting heart-rending farewells to life and their comrades as they were led away to execution. But in general, it was immeasurably easier to study in prison than as an underground militant at liberty."

The prison had a good library and during his stay he took the opportunity to improve his education. Kirov returned to revolutionary activity after his release and in 1915 he was once again arrested for printing illegal literature. After a year in custody he moved to the Caucasus. After the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March, 1917, George Lvov was asked to head the new Provisional Government in Russia. Lvov allowed all political prisoners to return to their homes. Kirov joined the other Bolsheviks in now attempting to undermine the government.

After the Russian Revolution he became commander of the Bolshevik military administration in Astrakhan. He also fought in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War until the defeat of General Anton Denikin in 1920. The following year Kirov was put in charge of the Azerbaijan party organization.

Sergey Kirov loyally supported Joseph Stalin and in 1926 he was rewarded by being appointed head of the Leningrad party organization. He joined the Politburo in 1930 and now one of the leading figures in the party, and many felt that he was being groomed for the future leadership of the party by Stalin. However, this was not the case as Stalin saw him as a rival. As Edward P. Gazur has pointed out: "In sharp contrast to Stalin, Kirov was a much younger man and an eloquent speaker, who was able to sway his listeners; above all, he possessed a charismatic personality. Unlike Stalin who was a Georgian, Kirov was also an ethnic Russian, which stood in his favour."

In the summer of 1932 Martemyan Ryutin wrote a 200 page analysis of Stalin's policies and dictatorial tactics, Stalin and the Crisis of the Proletarian Dictatorship. Ryutin argues: "The party and the dictatorship of the proletariat have been led into an unknown blind alley by Stalin and his retinue and are now living through a mortally dangerous crisis. With the help of deception and slander, with the help of unbelievable pressures and terror, Stalin in the last five years has sifted out and removed from the leadership all the best, genuinely Bolshevik party cadres, has established in the VKP(b) and in the whole country his personal dictatorship, has broken with Leninism, has embarked on a path of the most ungovernable adventurism and wild personal arbitrariness."

Ryutin also wrote up a short synopsis of the work and called it a manifesto and circulated it to friends. General Yan Berzin obtained a copy and called a meeting of his most trusted staff to discuss and denounce the work. Walter Krivitsky remembers Berzen reading excerpts of the manifesto in which Ryutin called "the great agent provocateur, the destroyer of the Party" and "the gravedigger of the revolution and of Russia."

Stalin interpreted Ryutin's manifesto as a call for his assassination. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Stalin also attacked those who were calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. Gregory Ordzhonikidze, Stalin's close friend, also agreed with Kirov. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

On 22nd September, 1932, Martemyan Ryutin was arrested and held for investigation. During the investigation Ryutin admitted that he had been opposed to Stalin's policies since 1928. On 27th September, Ryutin and his supporters were expelled from the Communist Party. Ryutin was also found guilty of being an "enemy of the people" and was sentenced to a 10 years in prison. Soon afterwards Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were expelled from the party for failing to report the existence of Ryutin's report. Ryutin and his two sons, Vassily and Vissarion were later both executed.

At the 17th Party Congress in 1934, when Sergei Kirov stepped up to the podium he was greeted by spontaneous applause that equalled that which was required to be given to Joseph Stalin. In his speech he put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. The members of the Congress gave Kirov a vote of confidence by electing him to the influential Central Committee Secretariat.

Stalin now found himself in a minority in the Politburo. After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public. He feared that this would undermine his authority in the party.

As usual, that summer Kirov and Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé. According to Alexander Orlov, who had been told this by Genrikh Yagoda, Stalin decided that Kirov had to die.

Yagoda assigned the task to Vania Zaporozhets, one of his trusted lieutenants in the NKVD. He selected a young man, Leonid Nikolayev, as a possible candidate. Nikolayev had recently been expelled from the Communist Party and had vowed his revenge by claiming that he intended to assassinate a leading government figure. Zaporozhets met Nikolayev and when he discovered he was of low intelligence and appeared to be a person who could be easily manipulated, he decided that he was the ideal candidate as assassin.

Zaporozhets provided him with a pistol and gave him instructions to kill Kirov in the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. However, soon after entering the building he was arrested. Zaporozhets had to use his influence to get him released. On 1st December, 1934, Nikolayev, got past the guards and was able to shoot Kirov dead. Nikolayev was immediately arrested and after being tortured by Genrikh Yagoda he signed a statement saying that Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev had been the leaders of the conspiracy to assassinate Kirov.

According to Alexander Orlov: "Stalin decided to arrange for the assassination of Kirov and to lay the crime at the door of the former leaders of the opposition and thus with one blow do away with Lenin's former comrades. Stalin came to the conclusion that, if he could prove that Zinoviev and Kamenev and other leaders of the opposition had shed the blood of Kirov". Victor Kravchenko has pointed out: "Hundreds of suspects in Leningrad were rounded up and shot summarily, without trial. Hundreds of others, dragged from prison cells where they had been confined for years, were executed in a gesture of official vengeance against the Party's enemies. The first accounts of Kirov's death said that the assassin had acted as a tool of dastardly foreigners - Estonian, Polish, German and finally British. Then came a series of official reports vaguely linking Nikolayev with present and past followers of Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev and other dissident old Bolsheviks."

Walter Duranty, the New York Times correspondent based in Moscow, was willing to accept this story. "The details of Kirov's assassination at first pointed to a personal motive, which may indeed have existed, but investigation showed that, as commonly happens in such cases, the assassin Nikolaiev had been made the instrument of forces whose aims were treasonable and political. A widespread plot against the Kremlin was discovered, whose ramifications included not merely former oppositionists but agents of the Nazi Gestapo. As the investigation continued, the Kremlin's conviction deepened that Trotsky and his friends abroad had built up an anti-Stalinist organisation in close collaboration with their associates in Russia, who formed a nucleus or centre around which gradually rallied divers elements of discontent and disloyalty. The actual conspirators were comparatively few in number, but as the plot thickened they did not hesitate to seek the aid of foreign enemies in order to compensate for the lack of popular support at home."

Robin Page Arnot, a member of the British Communist Party, also did his best to promote the theory that the conspiracy to kill Kirov had been led by Leon Trotsky: "In December 1934 one of the groups carried through the assassination of Sergei Mironovich Kirov, a member of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Subsequent investigations revealed that behind the first group of assassins was a second group, an Organisation of Trotskyists headed by Zinoviev and Kamenev. Further investigations brought to light definite counter-revolutionary activities of the Rights (Bukharin-Rykov organisations) and their joint working with the Trotskyists."

On this day in 1889 Liberal MP John Bright died. John Bright, the son of Jacob Bright, a self-made and successful cotton manufacturer, was born in Rochdale on 16th November, 1811. Jacob was deeply religious and sent John to Quaker schools in Lancashire and Yorkshire. This Quaker education helped to develop in Bright a passionate commitment to political and religious equality.

After his formal schooling came to an end, Bright joined the rapidly expanding family business. He also became involved in local politics and joined the campaign to end compulsory tax support of the Anglican Church in Rochdale.

In October 1837, Joseph Hume, Francis Place and John Roebuck formed the Anti-Corn Law Association in London. The following year Richard Cobden joined with Archibald Prentice to establish a branch of this organisation in Manchester. In March 1839 Cobden was instrumental in establishing a new centralized Anti-Corn Law League. Cobden was now able to organize a national campaign in favour of reform. Cobden was a friend of Bright and suggested he should join the League. Bright agreed and over the next few years he toured the country giving speeches on the need to reform the Corn Laws. Bright was an outstanding orator and he drew large crowds wherever he appeared.

In his speeches John Bright attacked the privileged position of the landed aristocracy and argued that their selfishness was causing the working class a great deal of suffering. Bright appealed to the working and middle classes to join together in the fight for free trade and cheaper food.

In 1843 Bright was elected to represent Durham in the House of Commons. In Parliament he campaigned for the repeal of the Corn Laws. He also supported those Whigs advocating universal suffrage and the secret ballot. However, unlike most Radicals, Bright was opposed to Parliament regulating the hours of factory workers. Bright feared that factory legislation would lower wages and threaten Britain's export trade and as a result voted against the 1844 Factory Act.

The failure of the Irish potato crop in 1845 and the mass starvation that followed, forced Sir Robert Peel and his Conservative government to reconsider the wisdom of the Corn Laws. Irish nationalists such as Daniel O'Connell also became involved in the campaign. Peel was gradually won over and in January 1846 a new Corn Law was passed that reduced the duty on oats, barley and wheat to the insignificant sum of one shilling per quarter became law.

Bright was now a national hero and he used his high standing to campaign for other progressive causes. As a Quaker Bright was opposed to the aggressive foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. Bright joined with Richard Cobden to campaign against the Crimean War (1854-1856). The two men were much abused by the press and some MPs even accused them of treason.

The British public shared the government's enthusiasm for the war and in the 1857 General Election, both Bright and Richard Cobden lost their seats in the House of Commons. However, five months later, he won a by-election in Birmingham. Bright refused to change his view on Britain's foreign policy. He blamed the Indian Mutiny of British misrule and advocated that the Indian people should be allowed to elect their own government.

Bright was now one of the leading advocates in the House of Commons for universal suffrage. In a speech made in 1858 he pointed out that only one out of six adult males had the vote in Britain and that less than 200,000 voters regularly returned more than 50% of all MPs. Bright called for an end to all rotten boroughs and the introduction of the secret ballot.

Bright was shocked by the outbreak of the American Civil War. As a Quaker he was totally opposed to slavery and was a passionate supporter of Abraham Lincoln. However, his religious views also stopped him for arguing in favour of Britain sending troops to help the Union forces against the Confederacy.

In 1865 Lord John Russell, leader of the Liberals in Parliament, became Prime Minister. Russell and William Gladstone, the government's leader of the House of Commons, were both supporters of parliamentary reform and although many Liberals were still opposed to universal suffrage, they were determined to try.

Bright toured the country and used his considerable public speaking skills to drum up support for the measure. However Russell's government found it impossible to get the bill passed by the House of Commons. When Russell resigned in 1866 he was replaced by the Earl of Derby and with the support of Benjamin Disraeli the new government managed to pass the 1867 Reform Act.

William Gladstone became Prime Minister in 1868 and as he was a great admirer of Bright he appointed him as his President of the Board of Trade. Bright now had the pleasure of seeing the Liberal government pass several measures that he had been advocating for many years. This included opening the universities to Nonconformists, the secret ballot and government funded education. Unfortunately ill-health forced him to retire from the Cabinet in December 1870.

The Liberals were in opposition between 1874 and 1880 but after William Gladstone became Prime Minister in 1870, Bright returned to government as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Bright objected to the Liberal government's foreign policy and when the British fleet attacked Egypt in 1882, he resigned from the Cabinet.

John Bright remained MP for Birmingham until his death on 27th March, 1889.

On this day in 1895 Roland Leighton, the son of Robert Leighton (1858-1934) and Marie Connor Leighton (1865-1941), was born in London on 27th March 1895. His father was literary editor at The Daily Mail, and was the author of popular adventure books for boys. His mother was also a writer and had published several novels.

Leighton was educated at Uppingham School where he met Edward Brittain and Victor Richardson. They were described by Roland's mother, as the "Three Musketeers". The three men joined the Officers' Training Corps (OTC). A fellow student, C.R.W. Nevinson, described the mood of the school as "appalling jingoism". The headmaster told them on Speech Day that: "If a man can't serve his country he's better dead."

As Alan Bishop has pointed out in his book, Letters From a Lost Generation (1998): "The OTC provided the institutional mechanism for public school militarism. But a more complex web of cultural ideas and assumptions, some taken from the classics, some from popular fiction, some even developed through competitive sports on the playing fields, was instilled by schoolmasters in their pupils, and contributed to the generation of 1914's overwhelming willingness to march off in search of glory." Leighton was an enthusiastic patriot and he was appointed as colour-sergeant of the OTC.

In June 1913, Edward Brittain introduced him to his sister, Vera Brittain. They soon developed a close relationship. Roland gave her a copy of Olive Schreiner's The Story of an African Farm. He told her that the main character, Lyndall, reminded him of her. Vera replied in a letter dated 3rd May 1914: "I think I am a little like Lyndall, and would probably be more so in her circumstances, uncovered by the thin veneer of polite social intercourse." Vera wrote in her diary that "he (Roland) seems even in a short acquaintance to share both my faults and my talents and my ideas in a way that I have never found anyone else to yet."

In July 1914, Leighton was awarded the Classical Postmastership at Merton College. On the outbreak of the First World War, he decided not to take his place at Oxford University in order to join the British Army. Vera Brittain wrote to Roland about his decision to take part in the war: "I don't know whether your feelings about war are those of a militarist or not; I always call myself a non-militarist, yet the raging of these elemental forces fascinates me, horribly but powerfully, as it does you. You find beauty in it too; certainly war seems to bring out all that is noble in human nature, but against that you can say it brings out all the barbarous too. But whether it is noble or barbarous I am quite sure that had I been a boy I should have gone off to take part in it long ago; indeed I have wasted many moments regretting that I am a girl. Women get all the dreariness of war and none of its exhilaration."

He was initially rejected due to poor eyesight but two months later obtained a commission in the Royal Norfolk Regiment. Lieutenant Leighton transferred to the 7th Worcester Regiment in an attempt to get to the Western Front as soon as possible. He arrived in the trenches at Armentieres in April 1915. Before actually seeing any action he became aware of the reality of war. Soon after arriving at the front-line trenches he wrote to Vera Brittain: "I went up yesterday morning to my fire trench, through the sunlit wood, and found the body of the dead British soldier hidden in the undergrowth a few yards from the path. He must have been shot there during the wood fighting in the early part of the war and lain forgotten all the time. The ground was slightly marshy and the body had sunk down into it so that only the toes of his boots stuck up above the soil. His cap and equipment were just by the side, half-buried and rotting away. I am having a mound of earth thrown over him, to add one more to the other little graves in the wood." He soon became disillusioned with the war. He told Vera later that month: "There is nothing glorious in trench warfare. It is all a waiting and a waiting and taking of petty advantages - and those who can wait longest win. And it is all for nothing - for an empty name, for an ideal perhaps - after all."

In a letter to Edward Brittain a couple of days later he spoke of his desire to return home: "Our position here is very strong, and in consequence life tends to become somewhat monotonous in time. The snipers are a chronic nuisance, but we do not get shelled very often, which is a distinct advantage. We have been here 10 days and have had only 1 killed and 6 wounded (none seriously). Armstrong got a bullet through his left wrist and has been sent home - lucky devil! They have stopped all leave other than sick leave now, so that I may be stuck out here for an indefinite period. As far as I can see, the war may last another two years if it goes on at the same rate as at present."

The trenches at Armentieres were very quiet and it was not until May that Leighton lost the first of his men: "One of my men has just been killed - the first. I have been taking the things out of his pockets and tying them round in his handkerchief to be sent back somewhere to someone who will see more than a torn letter, and a pencil, and a knife and a piece of shell. He was shot through the left temple while firing over the parapet. I did not actually see it - thank Heaven. I only found him lying very still at the bottom of the trench with a tiny stream of red trickling down his cheek onto his coat. He has just been carried away. I cannot help thinking how ridiculous it was that so small a thing should make such a change... I was talking to him only a few minutes before... I do not quite know how I felt at the moment. It was not anger (even now I have no feeling of animosity against the man who shot him) only a great pity, and a sudden feeling of impotence."

While on leave during August 1915 Roland Leighton became engaged to Vera Brittain. On his return to France he was stationed in trenches near Hebuterne, north of Albert. On the 26th November 1915 he wrote a letter to Vera that highlighted his disillusionment with the war. "It all seems such a waste of youth, such a desecration of all that is born for poetry and beauty. And if one does not even get a letter occasionally from someone who despite his shortcomings perhaps understands and sympathises it must make it all the worse... until one may possibly wonder whether it would not have been better to have met him at all or at any rate until afterwards. I sometimes wish for your sake that it had happened that way."

On the night of 22nd December 1915 he was ordered to repair the barbed wire in front of his trenches. It was a moonlit night with the Germans only a hundred yards away and Roland Leighton was shot by a sniper. His last words were: "They got me in the stomach, and it's bad." He died of his wounds at the military hospital at Louvencourt on 23rd December 1915. He is buried in the military cemetery near Doullens.

His friend, Victor Richardson, later recalled: "In the first place the wire in front of the trenches has to be kept in good order under all circumstances. The fact that there was a bright moon early in the night would not prevent the enemy making an attack later on in the night, or at dawn; and there is always the chance that if the wire was down they might get through, especially as any weak spots would have been marked down in daylight. This view would almost certainly be held by the officer responsible for the defence of the sector."

In her book, Testament of Youth (1933) Vera Brittain recalled visiting Roland's family home in Hassocks. "I arrived at the cottage that morning to find his mother and sister standing in helpless distress in the midst of his returned kit, which was lying, just opened, all over the floor. The garments sent back included the outfit that he had been wearing when he was hit. I wondered, and I wonder still, why it was thought necessary to return such relics - the tunic torn back and front by the bullet, a khaki vest dark and stiff with blood, and a pair of blood-stained breeches slit open at the top by someone obviously in a violent hurry. Those gruesome rages made me realise, as I had never realised before, all that France really meant."

On this day in 1912 James Callaghan was born in Portsmouth. After being educated at Portsmouth Northern School, he joined the staff of the Inland Revenue. In 1931 he became a member of the Labour Party and began work as a trade union official.

Callaghan was selected as the parliamentary candidate for South Cardiff and was elected to the House of Commons in the 1945 General Election and held minor posts in the government of Clement Attlee.

When Hugh Gaitskell died in 1963, Callaghan was one of the main contenders for the party leadership. Callaghan, who represented the right-wing of the party, was defeated by Harold Wilson.

When the Labour Party was elected in the 1964 General Election, Callaghan became the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In this post he created a great deal of controversy by introducing corporation tax and selective employment tax. After a long struggle, Callaghan was forced to devalue the pound in November 1967.

Callaghan resigned from office but was recalled as Home Secretary in 1968. He held the post until the defeat of the Labour government in the 1970 General Election.

Edward Heath and his Conservative government came into conflict with the trade unions over his attempts to impose a prices and incomes policy. His attempts to legislate against unofficial strikes led to industrial disputes. In 1973 a miners' work-to-rule led to regular power cuts and the imposition of a three day week. Heath called a general election in 1974 on the issue of "who rules". He failed to get a majority and Harold Wilson and the Labour Party were returned to power.

Wilson appointed Callaghan as his foreign secretary. In this post he had responsibility for renegotiating Britain's terms of membership of the European Economic Community (ECC). in 1975 Callaghan was demoted to the position of minister of overseas development.

Now aged 63, political commentators thought Callaghan's political career was coming to an end. However, when Harold Wilson resigned in 1976, Callaghan surprisingly defeated Roy Jenkins and Michael Foot for the leadership of the Labour Party.

The following year Callaghan, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey, controversially began imposing tight monetary controls. This included deep cuts in public spending on education and health. Critics claimed that this laid the foundations of what became known as monetarism. In 1978 these public spending cuts led to a wave of strikes (winter of discontent) and the Labour Party was easily defeated in the 1979 General Election.

Margaret Thatcher became the new prime minister and Callaghan was leader of the opposition until he resigned in 1980. Callaghan was made a life peer in 1987. His autobiography, Time and Chance, was published in 1987.

James Callaghan died on 26th March, 2005.

On this day in 1914 Eva Gore Booth publishes an article in Votes for Women “Equal Pay for Equal Work”.

Eva Gore-Booth, the daughter of Sir Henry Gore-Booth, was born at Lissadell House, County Sligo, Ireland on 22nd May, 1870. Gore-Booth, always attempted to act as a good landlord and provided free food for his tenants during the 1879-80 famine. It was probably the example of Gore-Booth that help develop in his two daughters, Eva and Constance Gore-Booth, a deep concern for the poor.

According to her biographer, Gifford Lewis, Eva Gore-Booth was "studious and introspective, she was quite different from her flamboyant and more robust elder sister Constance... in appearance she was willowy and frail, and she attracted attention with her fair hair and eager expression".

Eva suffered from poor health and in 1896 she travelled to Italy where she met Esther Roper. Her biographer, Margaret M. Jensen, argues that they "became immediate and lifelong companions". Roper was very interested in the subject of women's suffrage and was secretary of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage. In this role she tried to recruit working-class women from the emerging trade union movement. The author of Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper (1998) has argued: "For the first time Eva was able to talk to a kindred spirit. Captivated by the woman and her cause, she impulsively decided to leave Ireland and join Esther in the suffrage cause in Manchester."

In 1897 Eva moved into Esther's home in Manchester. At first under Esther's influence she devoted herself to trade unionism and women's suffrage, but later became involved in adult education for women and working with the Manchester University Settlement. In 1901, Christabel Pankhurst, who was at that time a student at Manchester University, joined their trade union campaign. She also met her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a member of the the Manchester branch of the NUWSS.

Sylvia Pankhurst also got to know Eva during this period. Later she was to say: "Eva Gore-Booth had a personality of great charm... Christabel adored her, and when Eva suffered from neuralgia, as often happened, would sit with her for hours massaging her head. To all of us at home this seemed remarkable indeed, for Christabel had never been willing to act the nurse to any other human being."

Fran Abrams the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003), has argued that: "Christabel Pankhurst had formed a close friendship with Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, suffrage campaigners who lived together in Manchester. Her relationship with Eva, in particular, had become intense enough to excite a great deal of comment from her family - according to Sylvia Pankhurst."

In 1903 Eva and Esther established the Lancashire and Cheshire Women's Textile and Other Workers Representation Committee. That year they also they organized a suffrage petition with 30,000 signatures. Eva also co-edited the Women's Labour News, a quarterly journal aimed at uniting women workers. She was also active in the socialist group, the Independent Labour Party.

Emmeline Pankhurst, with the help of her three daughters,Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote and therefore initially received the support of Esther and Eva. However, she later disapproved of their use of violence.

Eva Gore-Booth published a volumes of poetry, Unseen Kings in 1904. She continued to be interested in the struggle for women's rights and in the 1908 joined her sister, Constance Markievicz, and other suffragettes, including Annie Kenney, May Billinghurst and Adela Pankhurst, in the campaign against Winston Churchill in the parliamentary election in Manchester North West.

In 1913 Eva and Esther Roper moved to London. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, the NUWSS declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although its leader, Millicent Fawcett, supported the First World War effort she did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. Eva and Esther were both pacifists and disagreed with this strategy. Despite pressure from the majority of members, who held similiar views to Eva, Fawcett refused to argue against the war. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union."

In 1914 they joined the No-Conscription Fellowship, an organisation formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred." As Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has pointed out: "Though limiting itself to campaigning against conscription, the N.C.F.'s basis was explicitly pacifist rather than merely voluntarist.... In particular, it proved an efficient information and welfare service for all objectors; although its unresolved internal division over whether its function was to ensure respect for the pacifist conscience or to combat conscription by any means"

Eva and Esther resigned from the NUWSS over the issue of the First World War and helped establish the Women's Peace Crusade. Other members included Charlotte Despard, Selina Cooper, Margaret Bondfield, Ethel Snowden, Katherine Glasier, Helen Crawfurd, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington and Mary Barbour.

In 1916 she published another volume of poetry, Death of Fionavar (1916). Eva was also a member of a group that opposed gender stereotyping and helped publish its journal Urania. She was the leading figure who organised the successful reprieve of the death sentence passed on her sister Constance Markievicz following the Easter Rising.

Eva Gore-Booth died of cancer in Hampstead on 30th June, 1926. Esther Roper was at her bedside and remarked: "At the end she looked up with that exquisite smile that always lighted up her face when she saw one she loved, then closed her eyes and was at peace." Gore-Booth was buried in St John's Churchyard. Her sister, Constance Markievicz, did not attend the funeral, saying she "simply could not face it all." After her death Roper edited and introduced The Poems of Eva Gore-Booth (1929).

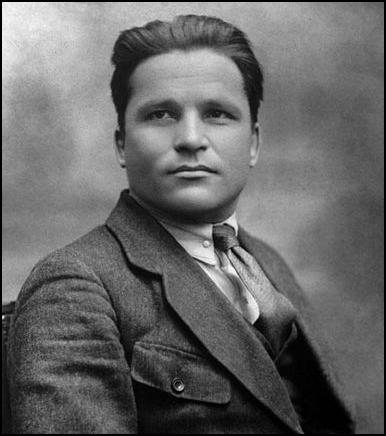

On this day in 1914 Budd Schulberg, the son of the Hollywood movie producer, Benjamin Schulberg, was born in New York on 27th March, 1914. His father was a former screenwriter who had risen to head of production at Paramount Studios. His mother, Adeline Schulberg, was a literary agent who had been an active member of the suffrage movement.

In his autobiography, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince (1981): "For, by the time I appeared in 1914, my father was working for one of the first film tycoons, the diminutive, untiring immigrant fur worker, Adolph Zukor, whose Famous Players Company was still a fledgling. For writing scenarios and publicity, (my father) had now achieved the lordly salary of fifty dollars a week. And he was moonlighting: writing a series of four one-reel documentaries on Sylvia Pankhurst, the English suffragist leader, who had come to America to promote the cause, and who had been dragged off to jail from the meeting my mother had attended. It was through Adeline's connections with the movement that my father had gotten the assignment, at fifty dollars per reel. So my birth had been financed in true collaboration: my father's screenwriting skills married to my mother's interest in the feminist pioneers. This was a first for all three of us: my first moments on earth, my father's first documentary film, and my mother's first efforts as a writer's agent.".

In 1931 Schulberg was sent to Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts. This was followed by Dartmouth College, New Hampshire. "In high spirits, I went up to Dartmouth... For me, the Dartmouth campus was love at first sight: the old New England village we drove through to reach the campus; the row of white 18th-century buildings; the inviting look of Baker Library; the coziness of its Tower Room; the sound of the chimes; the White Mountains in the background; the wide Connecticut River separating the college from the rolling green hills rising to the Green Mountains of Vermont; the impressive daily newspaper I longed to work on. The look of the student body appealed to me, checked wool shirts and windbreakers, a rugged up-country look that fulfilled our image of Dartmouth as northern New England's answer to the effeteness of Harvard or the southern-gentleman tradition of Princeton."

Schulberg held left-wing views and in 1934 he visited the Soviet Union where he heard Maxim Gorky make a speech on socialist realism at the first Soviet Writers' Congress. He was also impressed by the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold. In 1936 Schulberg graduated from Dartmouth College. After returning to Hollywood he joined the Communist Party (1937-40). However, these views were not evident in his first two screenplays, Little Orphan Annie (1938) and White Carnival (1939). He also married Virginia Ray, a fellow member of the Communist Party.

Schulberg lost his job with Paramount Studios after the failure of White Carnival and he turned to writing novels. His first novel, a satire of Hollywood power and corruption, brought him into conflict with his father, Benjamin Schulberg, who feared the book would create an anti-semitic backlash. John Howard Lawson and Richard Collins of the Communist Party also suggested a more positive portrait of a strike led by the Screen Writers Guild. Schulberg refused and in 1940 left the party. What Makes Sammy Run? was published in 1941.

After divorcing his first wife in 1942, Budd Schulberg enlisted in the US Navy. He was assigned to a documentary film unit run by John Ford. In 1945 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and later that year he was assigned to gather photographic evidence to be used at the Nuremberg War Crimes trials.

On his return to the United States, Schulberg, began work on a novel about boxing, The Harder They Fall (1947). The book was based on the career of Primo Carnera and his fights with Jack Sharkey, Paulino Uzcudun, Tommy Loughran and Max Baer.

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) opened its hearings concerning communist infiltration of the motion picture industry. The chief investigator for the committee was Robert E. Stripling. The first people it interviewed included Ronald Reagan, Gary Cooper, Ayn Rand, Jack L. Warner, Robert Taylor, Adolphe Menjou, Robert Montgomery, Walt Disney, Thomas Leo McCarey and George L. Murphy. These people named several possible members of the American Communist Party.

As a result their investigations, the HUAC announced it wished to interview nineteen members of the film industry that they believed might be members of the American Communist Party. This included Larry Parks, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

The first ten witnesses called to appear before the HUAC, Biberman, Bessie, Cole, Maltz, Scott, Trumbo, Dmytryk, Lardner, Ornitz and Lawson, refused to cooperate at the September hearings and were charged with "contempt of Congress". Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The courts disagreed and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentences were confirmed.

Richard Collins gave evidence on 12th April, 1951. He told the HUAC that he had been recruited to the American Communist Party by Budd Schulberg in 1936. He named John Howard Lawson as a leader of the party in Hollywood. Collins also claimed that fellow members of his communist cell included Ring Lardner Jr. and Martin Berkeley. He also named John Bright, Lester Cole, Paul Jarrico, Gordon Kahn, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Robert Rossen, Waldo Salt and Frank Tuttle. Collins estimated that the Communist Party in Hollywood during the Second World War had several hundred members and he had known about twenty of them.

When Schulberg heard the news he sent a telegram to the HUAC offering to provide evidence against former members of the American Communist Party. On 23rd May, 1951 Schulberg agreed to answer questions and admitted he joined the party in 1937. He also stated that Herbert Biberman, John Bright, Lester Cole, Richard Collins, Paul Jarrico, Gordon Kahn, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Waldo Salt had all been members. He also explained how party members such as Lawson and Collins had attempted to influence the content of his novel, What Makes Sammy Run?

Schulberg left the party in 1940 because of a dispute with Victor Jeremy Jerome: "It was suggested that I talk with a man by the name of V. J. Jerome, who was in Hollywood at that time. I went to see him... I didn't do much talking. I listened to V. J. Jerome. I am not sure what his position was, but I remember being told that my entire attitude was wrong; that I was wrong about writing; wrong about this book, wrong about the party; wrong about the so-called peace movement at that particular time; and I gathered from the conversation in no uncertain terms that I was wrong. I don't remember saying much. I remember it more as a kind of harangue. When I came away I felt maybe, almost for the first time, that this was to me the real face of the party. I didn't feel I had talked to just a comrade. I felt I had talked to someone rigid and dictatorial who was trying to tell me how to live my life, and as far as I remember, I didn't want to have anything more to do with them."

After giving evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee Schulberg was free to return to Hollywood scriptwriting. He worked with Elia Kazan, another former Communist Party member who named names, on the Academy Award winning film, On the Waterfront (1954). Schulberg won one of the film's eight oscars. A collection of short stories, Some Faces in the Crowd, was published in 1954. Other films that he wrote the screenplay for included The Harder They Fall (1956) and A Face in the Crowd (1957).

Schulberg retained his liberal views and founded the Watts Writers Workshop in 1964 and the Frederick Douglass Creative Arts Centre in New York City in 1971. He later received the Amistad award for his work with African-American writers. His autobiography, Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince was published in 1981.

Budd Schulberg, who was married four times and had fathered five children, died on 5th August 2009.

On this day in 1931 writer Arnold Bennett died. Bennett, the son of a solicitor, was born in Hanley, Staffordshire, in 1867. Educated locally and at London University, he became a solicitor's clerk, but later transferred to journalism, and in 1893 became assistant editor of the journal Woman.

Bennett published his first novel The Man from the North in 1898. This was followed by Anna of the Five Towns (1902), The Old Wives' Tale (1908), Clayhanger (1910), The Card (1911) and Hilda Lessways (1911).

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Charles Mastermanthe head of the War Propaganda Bureau (WPB) invited twenty-five leading British authors to Wellington House, to discuss ways of best promoting Britain's interests during the war. Those who attended the meeting included Bennett, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, William Archer, G. K. Chesterton, Sir Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells.

Bennett soon became one of the most important figures in this secret organisation. His first contribution to the propaganda effort was Liberty: A Statement of the British Case. It first appeared as an article in the Saturday Evening Post. In December it was expanded and published as a pamphlet by the War Propaganda Bureau. To disguise the fact it was a government publication, the WPB used the Hodder and Stoughton imprint.

When George Bernard Shaw, who was unaware of the existence of the War Propaganda Bureau, attacked what he believed to be jingoistic articles and poems being produced by British writers during the war, Bennett was the one chosen to defend their actions in the press.

In June, 1915, the WPB arranged for Bennett to tour the Western Front. Bennett was deeply shocked by the conditions in the trenches and was physically ill for several weeks afterwards. His friend, Frank Swinnerton, later recalled, "he visited the front as a duty, and was horrified at what he saw and felt that he must not express that horror." Bennett agreed to provide an account of the war that would encourage men to join the British Army. The result was the pamphlet, Over There: War Scenes on the Western Front (1915).

In March, 1918, Lord Beaverbrook, the new Minister of Information, recruited Bennett and Charles Masterman to join his new three-man British War Memorial Committee (BWMC). Their job was to select artists to produce paintings that would help the war effort. Bennett was also appointed director of British propaganda in France.

After the war Arnold Bennett returned to writing novels such as Riceyman Steps (1923) and Imperial Palace (1930). Bennett also became a director of the New Statesman. Arnold Bennett died in 1931.

On this day in 1937 the British Battalion passes a resolution on the Spanish Civil War.

We the members of the British working class in the British Battalion of the International Brigade now fighting in Spain in defence of democracy, protest against statements appearing in certain British papers to the effect that there is little or no interference in the civil war in Spain by foreign Fascist Powers.

We have seen with our own eyes frightful slaughter of men, women, and children in Spain. We have witnessed the destruction of many of its towns and villages. We have seen whole areas which have been devastated. And we know beyond a shadow of doubt that these frightful deeds have been done mainly by German and Italian nationals, using German and Italian aeroplanes, tanks, bombs, shells, and guns.

We ourselves have been in action repeatedly against thousands of German and Italian troops, and have lost many splendid and heroic comrades in these battles.

We protest against this disgraceful and unjustifiable invasion of Spain by Fascist Germany and Italy; an invasion in our opinion only made possible by the pro-Franco policy of the Baldwin Government in Britain. We believe that all lovers of freedom and democracy in Britain should now unite in a sustained effort to put an end to this invasion of Spain and to force the Baldwin Government to give to the people of Spain and their legal Government the right to buy arms in Britain to defend their freedom and democracy against Fascist barbarianism. We therefore call upon the General Council of the T.U.C. and the National Executive Committee of the Labour party to organise a great united campaign in Britain for the achievement of the above objects.

We denounce the attempts being made in Britain by the Fascist elements to make people believe that we British and other volunteers fighting on behalf of Spanish democracy are no different from the scores of thousands of conscript troops sent into Spain by Hitler and Mussolini. There can be no comparison between free volunteers and these conscript armies of Germany and Italy in Spain.

Finally, we desire it to be known in Britain that we came here of our own free will after full consideration of all that this step involved. We came to Spain not for money, but solely to assist the heroic Spanish people to defend their country's freedom and democracy. We were not gulled into coming to Spain by promises of big money. We never even asked for money when we volunteered. We are perfectly satisfied with our treatment by the Spanish Government; and we still are proud to be fighting for the cause of freedom in Spain. Any statements to the contrary are foul lies.

On this day in 1945 the last V-2 Flying Bomb lands on Britain. In the summer of 1942, Germany began working on two new secret weapon, the V-1 Flying Bomb, a pilotless monoplane that was powered by a pulse-jet motor and carried a one ton warhead. It was launched from a fixed ramp and travelled at about 350 mph and 4,000 feet and initially had a range of 150 miles (later 250 miles).

Germany fired 9,521 V-I bombs on southern England. Of these 4,621 were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire or by RAF fighters. An estimated 6,184 people were killed by these flying bombs. By August only 20 per cent of these bombs were reaching England.

The second secret weapon, the V-2 Rocket, was developed by Wernher von Braun, Walter Dornberger and Hermann Oberth at the rocket research station at Peenemunde.

The V-2 was first used in September, 1944. Like the V-1 Flying Bomb it carried a one ton warhead. However, this 14 metres (47 feet) long, liquid-fuelled rocket was capable of supersonic speed and could fly at an altitude of over 50 miles. As a result it could not be effectively stopped once launched.

Over 5,000 V-2s were fired on Britain. However, only 1,100 reached Britain. These rockets killed 2,724 people and badly injured 6,000. After the D-Day landings, Allied troops were on mainland Europe and they were able to capture the launch sites and by March, 1945, the attacks came to an end.