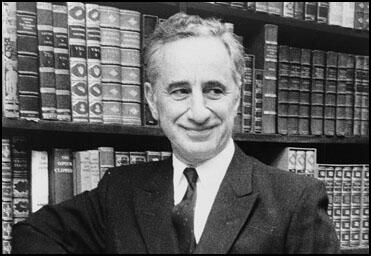

Elia Kazan

Elia Kazan (Kazanjoglous) was born in Constantinople, Turkey, on 7th September, 1909. Four years later the Kazan family moved to the United States. Kazan attended Williams College in Massachusetts before studying at the Drama School at Yale University.

In 1932 Kazan joined the Group Theatre in New York led by Lee Strasberg. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues. Those involved in the group included John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg and Lee J. Cobb.

Kazan joined the American Communist Party in 1934 and the following year appeared in Waiting for Lefty, a play by a fellow party member, Clifford Odets. Kazen became active in the Actors Equity Association. He worked closely with Philip Loeb, a fellow member of the American Communist Party.

Kazen recalled in his autobiography, Elia Kazan: A Life (1989): "In 1934, when I was in the Party, we helped start a left-wing movement in a very conservative Actors' Equity Association. Our prime goal was to secure rehearsal pay for the working actor and to limit the period when a producer could decide to replace an actor in rehearsal without further financial obligation... I was working on reforming Equity with a fine man named Phil Loeb... Our cause was so just that now, looking back, it's hard to believe there was any opposition to what we were proposing. Still it wasn't an easy to fight to win."

Kazan also appeared as an actor in two movies: City for Conquest (1940) and Blues in the Night (1941). In 1947 Kazan, Lee Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford established the Actors Studio, where they pioneered the idea of Method Acting (a system of training and rehearsal for actors which bases a performance upon inner emotional experience).

Kazan directed All My Sons, a play by a young playwright, Arthur Miller. It opened at the Coronet Theatre on 29th January, 1947, and starred Ed Begley, Karl Malden and Arthur Kennedy. As Michael Ratcliffe pointed out: "A family tale of corrupt profiteering at home that led to the death of US pilots abroad, it exploded in the pause between victory and the attempted press-ganging of show business for Washington's cold war. From this point on, Miller's best scenes display a mastery of conversation, a gift for sketching vivid characters on the margins of a play, and a narrative talent for seizing the spectator's attention from the start." The play won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award and ran for 328 performances.

Miller sent details of his next play, Death Of A Salesman, to Kazan. He thought it was "a great play" and that the character of Willy Loman reminded him of his father. Miller later recalled that Kazan was the "first of a great many men - and women - who would tell me that Willy was their father." The play opened at the Morosco Theatre on 10th February, 1949. It was directed by Kazan and featured Lee J. Cobb (Willy Loman), Mildred Dunnock (Linda), Arthur Kennedy (Biff) and Cameron Mitchell (Happy).

Death Of A Salesman played for 742 performances and won the Tony Award for best play, supporting actor, author, producer and director. It also won the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play. Miller was himself highly critical of the play: "I knew nothing of Brecht then or of any other theory of theatrical distancing: I simply felt that there was too much identification with Willy, too much weeping, and that the play's ironies were being dimmed out by all this empathy."

Kazan also worked with Tennessee Williams on the Pulitzer Prize winning, A Streetcar Named Desire (1947). Kazan also became interested in movies and directed three films that dealt with social issues: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), Gentlemen's Agreement (1947), The Sea of Grass (1947) and Boomerang! (1947).

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In September 1947, the HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named several people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

Ten of those named: Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Samuel Ornitz, Dalton Trumbo, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson and Alvah Bessie refused to answer any questions put by the HUAC. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and all were found guilty of contempt of congress and each was sentenced to between six and twelve months in prison.

Kazan was known for his left-wing views and he was eventually called to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Controversially, Kazan decided to name eight people who had been fellow members of the American Communist Party in the 1930s. As a result, these people were called before the HUAC. Those that refused to name names, were blacklisted. Kazan later claimed he felt no guilty about what he had done: "There's a normal sadness about hurting friends, but I would rather hurt them a little than hurt myself a lot."

As a reward for his co-operation, Kazan was allowed to continue working in Hollywood. Films included and Pinky (1949), Panic in the Streets (1950), A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Viva Zapata! (1952) and Man on a Tightrope (1953).

On the Waterfront (1954), was an attempt to justify the morality of providing information on friends to people in authority. Budd Schulberg, the writer and the actor Lee J. Cobb, who both testified before the HUAC, also worked on the film. Other movies directed by Kazan during this period included East of Eden (1955), Baby Doll (1956) and Splendor in the Grass (1960).

Kazan also wrote several novels including America, America (1962), The Arrangement (1967), The Assassins (1972) and The Understudy (1974). In his autobiography, A Life (1988), Kazan attempted to defend his decision to give names of his former friends to the House of Un-American Activities Committee. One critic has described it as "maybe the best show business autobiography of the century."

Elia Kazan, who was married three times (Molly Thatcher, Barbara Loden and Frances Rudge), died on 28th September, 2003. The film critic, David Thompson, wrote at the time of his death: "There were people who hadn't spoken to him in over 45 years; and who had crossed the street sometimes to avoid him. They had their reasons, good reasons; but everyone has his reasons. And the man is dead now, and his size cannot be denied any longer. Crossing the street will not do. Elia Kazan was a scoundrel, maybe; he was not always reliable company or a nice man. But he was a monumental figure, the greatest magician with actors of his time, a superlative stage director, a film-maker of real glory, a novelist, and finally, a brave, candid, egotistical, self-lacerating and defiant autobiographer - a great, dangerous man, someone his enemies were lucky to have."

Primary Sources

(1) In his autobiography Timebends, Arthur Miller describes being told by Elia Kazan about his intention to testify to the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

Listening to him I grew frightened. There was a certain gloomy logic in what he was saying: unless he came clean he could never hope, in the height of his creative powers, to make another film in America, and he would probably not be given a passport to work abroad either. If the theatre remained open to him, it was not his primary interest anymore; he wanted to deepen his film life, that was where his heart lay, and he had been told in so many words by his old boss and friend Spyros Skouras, president of Twentieth Century Fox, that the company would not employ him unless he satisfied the Committee.

I could only say that I thought this would pass and that it had to pass because it would devour the glue that kept the country together if left to its own unobstructed course. I said that it was not the Reds who were dispensing our fears now, but the other side, and it could not go indefinitely, it would someday wear down the national nerve. And then there might be regrets about this time. But I was growing cooler with the thought that as unbelievable as it seemed, I could still be up for sacrifice if Kazan knew I attended meetings of the Communist Party writers years ago and had made a speech at one of them.

(2) When he appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee on 12th April, 1952, Elia Kazan explained how the American Communist Party had attempted to take over the Group Theatre in the 1930s.

I was instructed by the Communist unit to demand that the group be run "democratically." This was a characteristic Communist tactic; they were not interested in democracy; they wanted control. They had no chance of controlling the directors, but they thought that if authority went to the actors, they would have a chance to dominate through the usual tricks of behind-the-scenes caucuses, block voting, and confusion of issues. This was the specific issue on which I quit the Party. I had enough regimentation, enough of being told what to think and say and do, enough of their habitual violation of the daily practices of democracy to which I was accustomed. The last straw came when I was invited to go through a typical Communist scene of crawling and apologizing and admitting the error of my ways. I had had a taste of police-state living and I did not like it.

(3) Elia Kazan, statement, New York Times (13th April, 1952)

In the past weeks intolerable rumors about my political position have been circulating in New York and Hollywood. I want to make my stand clear:

I believe that Communist activities confront the people of this country with an unprecedented and exceptionally tough problem. That is, how to protect ourselves from a dangerous and alien conspiracy and still keep the free, open, healthy way of life that gives us self-respect.

I believe that the American people can solve this problem wisely only if they have the facts about Communism. All the facts. Now, I believe that any American who is in possession of such facts has the obligation to make them known, either to the public or to the appropriate Government agency.

Whatever hysteria exists - and there is some, particularly in Hollywood - is inflamed by mystery, suspicion and secrecy. Hard and exact facts will cool it. The facts I have are sixteen years out of date, but they supply a small piece of background to the graver picture of Communism today. I have placed these facts before the House Committee on Un-American Activities without reserve and I now place them before the public and before my co-workers in motion pictures and in the theatre.

I joined the Communist Party late in the summer of 1934. I got out a year and a half later. I have no spy stories to tell, because I saw no spies. Nor did I understand, at that time, any opposition between American and Russian national interest. It was not even clear to me in 1936 that the American Communist Party was abjectly taking its orders from the Kremlin.

Firsthand experience of dictatorship and thought control left me with an abiding hatred of these. It left me with an abiding hatred of Communist philosophy and methods and the conviction that these must be resisted always. It also left me with the passionate conviction that we must never let the Communists get away with the pretense that they stand for the very things which they kill in their own countries.

I am talking about free speech, a free press, the rights of property, the rights of labor, racial equality and, above all, individual rights. I value these things. I take them seriously. I value peace, too, when it is not bought at the price of fundamental decencies. I believe these things must be fought for wherever they are not fully honored and protected whenever they are threatened.

(4) Elia Kazan, was interviewed by Edwin Newman on the television programme, Speaking Freely, in 1972.

Edwin Newman: I suppose one of the things for which you were most criticized you appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and confessed that you had been briefly for eighteen months a Communist when you were young. And you named I think it was seven other people who had been Communists. A good many people thought you shouldn't have named any other names whatever you said about yourself. You have never over the years said much about that. Is there anything you want to say about it?

Elia Kazan: Well, not really. I think when it is understood from the point of 1972 it is one thing and when it is understood in the context of what was going on in 1952 and how we felt in 1952, it is another. We knew about a society that the left was idealizing then, the Russian society. We knew that it was a slave society. We had a good idea how many people were being killed. I've often wondered how some of the people who criticized me went through those years and stayed behind Russia, continued to idealize it when they knew what was happening. I've felt sad about it or bad about it, and I've sometimes felt - well, I would do the same thing over again. I think I spoke up not for any reason of money or security or anything else, but because I actually felt it. If I made a mistake, then that was a mistake that was honestly made.

(5) In his autobiography Elia Kazan described how Harold Clurman had influenced him.

I learned from Harold that a director's first task is to make his actors eager to play their parts. He had a unique way of talking to actors - I didn't have it and I never heard of another director who did; he turned them on with his intellect, his analyses and his insights. But also by his high spirits. Harold's work was joyous. He didn't hector his actors from an authoritarian position; he was a partner, not an overlord, in the struggle of production. He'd reveal to each actor at the onset a concept of his or her performance, one the actor could not have anticipated and could not have found on his own. Harold's visions were brilliant; actors were eager to realize them. They were also full of compassion for the characters' dilemmas, their failings and their aspirations.

(6) Elia Kazan, in conservation with is third wife, Frances Rudge (1987)

What I'm mad at nowadays is, for instance, mortality. I've passed 78 and have only recently found how to enjoy life. For one thing I've stopped worrying about what people think of me - or so I like to believe. I used to spend most of my time straining to be a nice guy so people would like me. Now I'm out of show business and I've become my true grumpy self.

(7) Roger Ebert, Chicago Sunday Times (29th September, 2003)

In the McCarthy era, the House Un-American Activities Committee held widely publicized hearings, asking Hollywood figures to name others they knew to be communists. When Mr. Kazan cooperated, he was shunned and scorned by many of his colleagues for the rest of his life.

Mr. Kazan was adamant that he had done the right thing. In his autobiography, Elia Kazan: A Life (1988), he said he had come to hate the party, which "should be driven . . . into the light of scrutiny." His action was taken, he said, "out of my own true self."

Those who refused to testify said the hearings were show trials, like those conducted by Stalin. They pointed out that Communist party membership was legal. A year after testifying, Mr. Kazan directed his greatest film, On the Waterfront, in which his hero Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando) names names before a panel investigating labor practices.

The movie was written by Budd Schulberg, a writer who also named former communists, and the movie was seen by many as a response to their critics. Mr. Kazan said it wasn't. Whether it was or not, it is considered one of the greatest of all American films, was nominated for 11 Oscars and won seven, including best picture, director, actor, actress, screenplay and cinematography.

(8) David Thompson, The Guardian (29th September, 2003)

(In 1951) he (Kazan) heard that the House Committee on Un-American Activities wanted to talk to him. This was no surprise. The committee had been active since 1947, and Kazan was a very obvious target. There was a questioning session, early in 1952, at which he refused to name names. People in power in the picture business told him his career was in jeopardy. He went back and named names.

"Concerned friends", he would write, "have asked me why I didn't take the 'decent' alternative, tell everything about myself and not name the others in the Group. But in the end that was not what I wanted. Perhaps ex-communists are particularly unrelenting against the party. I believed that this committee, which everyone scorned - I had plenty against them too - had a proper duty. I wanted to break open the secrecy."

In which case, of course, he should have talked the first time. The defence was typical of Kazan, and it was underlined in a piece written by his wife which they ran as an exculpatory ad in the New York Times. It was a moment of divide; many people would never talk to Kazan again - they pointed to his rising career, and to others that were crushed. They saw nastiness in the self-serving defence and predicted moral disaster for the man.

There were people who hadn't spoken to him in over 45 years; and who had crossed the street sometimes to avoid him. They had their reasons, good reasons; but everyone has his reasons. And the man is dead now, and his size cannot be denied any longer. Crossing the street will not do. Elia Kazan was a scoundrel, maybe; he was not always reliable company or a nice man. But he was a monumental figure, the greatest magician with actors of his time, a superlative stage director, a film-maker of real glory, a novelist, and finally, a brave, candid, egotistical, self-lacerating and defiant autobiographer - a great, dangerous man, someone his enemies were lucky to have.

There is no way his crammed career and conflicting impulses can be reduced to a short obituary. To list all his credits would take up the space, and leave no room for a proper account of his truly ugly face, made magnetic by the way his reproachful eyes watched you. He was edgy, belligerent, seductive, rhapsodic, brutal, a soaring humanist one moment and a piratical womaniser the next. Until old age and illness overcame him, he was ferociously and competitively alive. To be with him was to know that, in addition to everything else he had done, he could have been a hypnotic actor or an inspiring political leader.

(9) The Times (29th September, 2003)

Inexplicably to colleagues in the film industry who had shared his ideals (like him many of them had been members of the Communist Party in the 1930s), Kazan was to commit what many still consider one of the great ideological betrayals in American performing arts history. In the early 1950s he informed the House Un-American Activities Committee, then engaged in a witch-hunt against communism, that he would do "anything you consider valuable or necessary to help".

He was always to defend his actions by claiming that as a liberal, he felt that the secrecy that aided communism posed a threat to the very existence of a free and democratic United States. (Lillian Hellman described this stance as "pious shit", and remained firmly of the opinion that Kazan was concerned only with saving his own creative skin.)

Be that as it may, Kazan’s "help" to the committee included his naming of a number of prominent figures who either had, or had had, links with the Communist Party. All of these were blacklisted and most of them had their creative lives ruined as a result. Those who had careers blighted by Kazan’s revelations - and the many more who came to grief because they were named by others - never forgave such a man as Kazan for his part in the betrayal. When, in 1999, it was decided to award Kazan an honorary Oscar for his lifetime of achievement, the announcement was greeted with repugnance in many quarters. At the ceremony, in March of that year, several members of the audience conspicuously refused to clap.

(10) The Telegraph (29th September, 2003)

In A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) Kazan turned on the emotional heat which was to give his films their pungent flavour. Having already directed Brando in the Broadway production, Kazan was able to intensify the atmosphere. The contrast between the brooding, instinctive Brando as Stanley Kowalski and the conventional histrionics of Vivien Leigh as Blanche gave the film its own tension.

Kazan worked again with Brando in Viva Zapata! (1952) and On the Waterfront (1954). These established him as a film-maker rather than an adapter of plays for the screen. By integrating the Method acting of Brando, Rod Steiger and Lee J Cobb with the location photography of the New York docks, On the Waterfront yielded some of the most powerfully realistic moments in American film history.

Brando won an Academy award for Waterfront; Kazan won the Oscar for best film, and was named best director; while Eva Marie Saint received the award for best supporting actress. What gave the film an added edge were its parallels between Brando's character as a docker tempted to sneak on his fellow trades unionists and Kazan's own recent evidence to the House of Un-American Activities Committee about former Communist comrades in the theatre.

(11) Andrew Gumbel, The Independent (29th September, 2003)

There are those who can never forgive Elia Kazan, one of the towering figures of 20th-century American film and theatre, for naming names before the House Un-American Activities Committee at the height of the McCarthy era in 1952.

But as tributes flowed in yesterday, following his death at the age of 94, the director who discovered Marlon Brando and James Dean and showcased the best of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams at last achieved a kind of peace.

Actors and colleagues hailed him as one of the seminal figures in American drama, a director who could bring the most intense passions out of his actors - he was a co-founder of the Actors Studio. He was also remembered as someone who could make intense social dramas, among them East of Eden, A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront, positively sizzle on the screen.

Kazan never apologised for his testimony, in which he denounced eight actors and writers, including the playwright Clifford Odets and the actress Paula Strasberg, as members of the Communist Party. In fact, he took out a full-page advertisement in The New York Times justifying his act.

(12) Mervyn Rothstein, New York Times (29th September, 2003)

To many critics, he was the best director of American actors in stage and screen history, discovering Marlon Brando, James Dean and Warren Beatty and redefining the craft of film acting. In 1953 the critic Eric Bentley wrote that "the work of Elia Kazan means more to the American theater than that of any current writer."

In Hollywood, seven of Kazan's films won a total of 20 Academy Awards. He won best-director Oscars for "Gentleman's Agreement," a 1947 indictment of anti-Semitism, and "On the Waterfront" in 1954. "On the Waterfront," a searing depiction of venality and corruption on the New Jersey docks, won eight Oscars. Kazan also received an Oscar for lifetime achievement in 1999.

The lifetime-achievement award was controversial because in 1952 Kazan angered many of his friends and colleagues when he acknowledged before the House Un-American Activities Committee that he had been a member of the Communist Party from 1934 to 1936 and gave the committee the names of eight other party members. He had previously refused to do so, and his naming of names prompted many people in the arts, including those who had never been Communists, to excoriate him for decades.

(13) Warren Beatty, interview with the Los Angeles Times (29th September, 2003)

Elia Kazan was my first teacher in movies, an indispensable mentor for me; inspiring, generous, unpretentious, pre-eminent in both the theatre and the movies. I am blessed to have had him as a friend.