On this day on 19th March

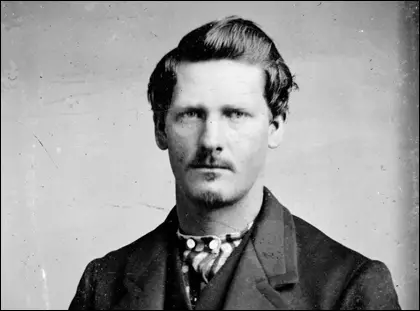

On this day in 1848 Wyatt Earp was born in Montmouth, Illinois. His father moved the family, to San Bernardino, California and joined his older brother, Virgil Earp, as a freighter-teamster between Wilmington to Prescott, Arizona (1866-68).

In 1870 Earp was elected constable of Lamar, Missouri. Later that year he married Urilla Sutherland but she died soon afterwards of typhoid. His job as constable came to an end when Earp was arrested for horse theft. He managed to escape and became a buffalo hunter in Kansas. Earp then moved to Wichita where he married a local prostitute. He also joined the Wichita police force. However, he was discharged in April 1876 after a fight with a fellow officer.

A few months later Earp joined the police force in Dodge City . In 1878 he was appointed assistant city marshal under Charles Bassett. While in the city he became friends with the former dentist and now a professional gambler, Doc Holliday.

Earp's record as a marshal was unimpressive and in September 1879 he left Dodge City and three months later reached Tombstone where he became a farmer. Earp's brothers, Virgil Earp, Morgan Earp and James Earp also lived in Tombstone. Earp's best friend, Doc Holliday, was also based in this fast-growing town.

Virgil Earp eventually became city marshal of Tombstone. Soon afterwards he recruited Wyatt Earp and Morgan Earp as "special deputy policemen". In 1880 the Earp family came into conflict with two families, the Clantons and the McLaurys. Ike Clanton, Phineas Clanton, Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury and Frank McLaury sold livestock to Tombstone. Virgil Earp brothers believed that some of these animals had been stolen from farmers in Mexico. Wyatt Earp was also convinced that the Clanton brothers had stolen one of his horses.

Wyatt Earp also came into conflict with John Behan, the sheriff of Cochise County. At first this started as a quarrel over a woman, Josephine Sarah Marcus. She had lived with Behan before becoming Earp's third wife. Earp also wanted Behan's job and planned to run against him in the next election. The two men also clashed over the decision by Behan to arrest Doc Holliday on suspicion of killing a stage driver during an attempted hold-up outside of town. Holliday protested his innocence and he was eventually released. In September 1881, Virgil Earp retaliated by arresting one of Behan's deputies, Frank Stilwell, for holding up a stagecoach.

On 25th October, Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury arrived in Tombstone. Later that day Doc Holliday got into a fight with Ike Clanton in the Alhambra Saloon. Holliday wanted a gunfight with Clanton, but he declined the offer and walked off.

The following day Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury were arrested by Virgil Earp and charged with carrying firearms within the city limits. After they were disarmed and released, the two men joined Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury, who had just arrived in town. The men gathered at a place called the OK Corral in Fremont Street.

Virgil Earp now decided to disarm Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury and recruited Wyatt Earp, Morgan Earp, James Earp and Doc Holliday to help him in this dangerous task. Sheriff John Behan was in town and when he heard what was happening he raced to Fremont Street and urged Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury to hand over their guns to him. They replied: "Not unless you first disarm the Earps".

Behan now headed towards the advancing group of men. He pleaded for Virgil Earp not to get involved in a shoot-out but he was brushed aside as the four men carried on walking towards the OK Corral. Virgil Earp said: "I want your guns". Billy Clanton responded by firing at Wyatt Earp. He missed and Morgan Earp successfully fired two bullets at Billy Clanton and he fell back against a wall. Meanwhile Wyatt Earp fired at Frank McLaury. The bullet hit him in the stomach and he fell to the ground.

Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury were both unarmed and tried to run away. Clanton was successful but Doc Holliday shot McLaury in the back. Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury, although seriously wounded, continued to fire their guns and in the next couple of seconds Virgil Earp, Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday were all wounded. Wyatt Earp was unscathed and he managed to finish off Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury.

Sheriff John Behan arrested Virgil Earp, Wyatt Earp, Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday for murder of Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury and Frank McLaury. However, after a 30 day trial Judge Wells Spicer, who was related to the Earps, decided that the defendants had been justified in their actions.

Over the next few months the Earp brothers struggled to retain hold control over Tombstone. Virgil Earp was seriously wounded by an attempted assassination and Morgan Earp was killed when he was playing billiards with Wyatt Earp on 18th March, 1882. Eyewitnesses claimed that Frank Stilwell was seen running from the scene of the crime. Three days later Stilwell's was found dead. A Mexican who was also implicated in the crime was also found murdered in a lumber camp. It is believed that Wyatt Earp was responsible for killing both men.

Earp was now forced to flee from Tombstone and eventually reached Colorado. Later he moved to Arkansas where he was jailed for theft in 1883.

In February, 1883, Luke Short moved to Dodge City and purchased the Long Branch Saloon with W. H. Harris. A power struggle now took place between Short and Nicholas B. Klaine, the editor of the Dodge City Times. In the election for mayor of the city later that year Klaine supported Larry Deger against Short's partner, W. H. Harris. Deger defeated Harris 214 to 143.

Soon after gaining power Deger published Ordinance No 70, an attempt to ban prostitution in Dodge City. Two days later the local police arrested female singers being employed in Short's Long Branch Saloon and accused of being prostitutes. That night Short and L.C. Hartman, the city clerk, exchanged gunfire in the street. Short was now arrested and forced to leave town.

Short had some powerful friends and in June 1883 he returned to Dodge City with Earp, Bat Masterson, Charlie Bassett, Doc Holliday and other well-known gunfighters such as, M. F. McLain, Neil Brown and W. F. Petillion. However, Deger and Klaine refused to be intimidated and when they refused to back down, Short and his friends had to accept defeat. In November 1883, Short and Harris sold the Long Branch Saloon and moved to Fort Worth.

In 1885 Earp was once again imprisoned for theft. After his release he opened a saloon in San Diego. He also attempted to breed racehorses in San Francisco.

In 1896 Earp agreed to referee the Bob Fitzsimmons-Tom Sharkey heavyweight fight in Oakland, California. Earp insisted that he should be allowed to carry a gun. This was needed when he controversially declared Tom Sharkey the winner, after he had taken a terrible beating and appeared on the verge of being knocked out. Earp also owned a saloon in Tonopah and Goldfield in Nevada before settling in Los Angeles in 1906.

In old age Wyatt Earp was befriended by Stuart N. Lake who agreed to become his biographer. Wyatt Earp died on 13th January, 1929 and the book, Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshall, was published two years later. The book was quickly denounced by people who knew Earp as being a very inaccurate account of his life. Allie Earp, the widow of Virgil Earp, described it as "a pack of lies".

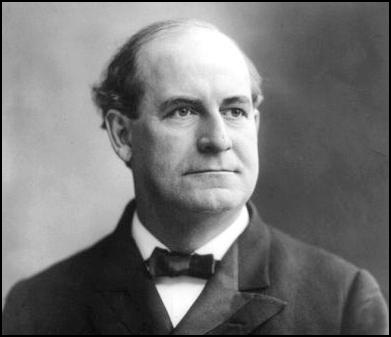

On this day in 1860 William Jennings Bryan, the son of Silas Lillard Bryan and Mariah Elizabeth Jennings, was born in Salem, Illinois, on 19th March, 1860. Bryan graduated from Illinois College in 1881 and afterwards studied law in Chicago at the Northwestern University School of Law.

Bryan married Mary Elizabeth Baird, a fellow law student, on 1st October, 1884. He practiced law in Jacksonville but in 1887 moved to the fast-growing Lincoln in Lancaster County. Bryan was an active member of the Democratic Party and in 1890 was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was only the second Democrat to be elected to Congress in the history of Nebraska.

Bryan soon established himself as one of the nation's leading orators. A Democratic with progressive views, he supported campaigns for graduated income tax, regulating child labour and women's suffrage. After his defeat 1894 he was appointed editor of the Omaha World Herald before becoming the Democratic presidential candidate in 1896. At the age of 36 he was the youngest man ever to win the nomination.

During the campaign Bryan became the first presidential candidate to use a car. His Republican opponent, William McKinley argued for high protective tariffs on foreign goods. This message was popular with America's leading industrialists and with the support of Mark Hanna, McKinley was able to raise $3,500,000 for his campaign. Outspending Bryan by 20 to 1, McKinley easily defeated his opponent by an electoral vote of 271 to 176.

Bryan was also the Democratic Party candidate in 1900. A devout anti-imperialist he urged a non-aggressive foreign policy. In one speech he argued: "The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights." He added: "Behold a republic standing erect while empires all around are bowed beneath the weight of their own armaments - a republic whose flag is loved while other flags are only feared." This policy was not popular with the American public and this time he was defeated by McKinley by 292 electoral votes to 155.

Bryan became editor of his own newspaper, The Commoner . However, his main source of income was as a public speaker. Over the next few years he toured America giving talks on current affairs. He argued: "Never be afraid to stand with the minority when the minority is right, for the minority which is right will one day be the majority." He usually charged $500 per speech in addition to a percentage of the profits. He invested some of this money in buying large areas of land in Nebraska and Texas.

Bryan was again selected as the Democratic candidate for the 1908 Presidential Election and John W. Kern, a progressive politician from Indiana, became his running mate. The Republican Party selected Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. Using the slogan: "Shall the People Rule?", Bryan campaigned in favour of new income and inheritance taxes. He also warned against the growing influence of corporations in elections and called for their donations to political parties to become public. Bryan went down to his largest defeat, winning only 162 electoral votes to Roosevelt's 321.

William Jennings Bryan returned to the lecture circuit where he continued to advocate progressive policies. This included arguing that religion was the foundation of morality, and individual and group morality was the foundation for peace and equality. However, in other ways he was a traditionalist and began attacking the ideas of Charles Darwin. He told one audience: "The parents have a right to say that no teacher paid by their money shall rob their children of faith in God and send them back to their homes skeptical, or infidels, or agnostics, or atheists." On another occasion he argued: "If we have to give up either religion or education, we should give up education."

In 1905 he suggested that "the Darwinian theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate, the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development."

In 1912 Theodore Roosevelt stood as the Progressive Party candidate against William H. Taft. This split the traditional Republican vote and enabled Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party candidate, to be elected. Wilson appointed Bryan as secretary of state. A passionate pacifist, Bryan convinced 31 nations to agree in principle to his proposal to accept a year's cooling-off period during political conflicts, allowing the dispute to be studied by an international commission. Bryan resigned from the government in protest against the way that President Wilson dealt with the sinking of the Lusitania. However, when the United States entered the First World War in 1917, Bryan gave his full support to the war effort.

As Bryan got older he became more conservative in his political attitudes. In June, 1924, the journalist, Heywood Broun, accused Bryan of being a supporter of the Ku Klux Klan. "For William Jennings Bryan is the very type and symbol of the spirit of the Ku Klux Klan. He has never lived in a land of men and women. To him this country has been from the beginning peopled by believers and heretics. According to his faith mankind is base and cursed. Human reason is a snare, and so Bryan has made oratory the weapon of his aggressions. When professors in precarious jobs have disagreed with him about evolution, Mr. Bryan has never argued the issue, but instead has turned bully and burned fiery crosses at their doors." Broun also criticised Bryan for not opposing Jim Crow laws.

In the early 1920s Bryan began a campaign to bring an end to the teaching of evolution in schools. Bryan argued in 1922: " Now that the legislatures of the various states are in session, I beg to call attention of the legislators to a much needed reform, viz., the elimination of the teaching of atheism and agnosticism from schools, colleges and universities supported by taxation. Under the pretense of teaching science, instructors who draw their salaries from the public treasury are undermining the religious faith of students by substituting belief in Darwinism for belief in the Bible. Our Constitution very properly prohibits the teaching of religion at public expense. The Christian church is divided into many sects, Protestant and Catholic, and it is contrary to the spirit of our institutions, as well as to the written law, to use money raised by taxation for the propagation of sects. In many states they have gone so far as to eliminate the reading of the Bible, although its morals and literature have a value entirely distinct from the religious interpretations variously placed upon the Bible."

Tennessee governor Austin Peay, agreed with Bryan and in 1925 he passed what became known as the Butler Act. This prohibited public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of man's origin. The law also prevented the teaching of the evolution of man from what it referred to as lower orders of animals in place of the Biblical account.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case challenging the constitutionality of this measure. John Thomas Scopes, a teacher at Rhea County High School in Dayton, Tennessee, was approached by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea, and asked if he would be willing to teach evolution at the Rhea County High School. Scopes agreed and was arrested on 5th May, 1925. America's most famous criminal lawyer, Clarence Darrow, offered to defend Scopes without a fee. Bryan agreed to help the prosecution by Arthur Thomas Stewart, the District Attorney. He was financed by the World Christian Fundamental Association.

The Scopes Trial began in Dayton on 11th July, 1925. Over 100 journalists arrived in the town to report on the trial. The Chicago Tribune installed its own radio transmitter and it became the first trial in American history to be broadcast to the nation. Three schoolboys testified that they had been present when Scopes had taught evolution in their school. When the judge, John T. Raulston, refused to allow scientists to testify on the truth of evolution, Clarence Darrow called William Jennings Bryan to the witness stand. This became the highlight of the 11 day trial and many independent observers believed that Darrow successfully exposed the flaws in Bryan's arguments during the cross-examination.

In his closing speech Bryan pointed out: "Let us now separate the issues from the misrepresentations, intentional or unintentional, that have obscured both the letter and the purpose of the law. This is not an interference with freedom of conscience. A teacher can think as he pleases and worship God as he likes, or refuse to worship God at all. He can believe in the Bible or discard it; he can accept Christ or reject Him. This law places no obligations or restraints upon him. And so with freedom of speech, he can, so long as he acts as an individual, say anything he likes on any subject. This law does not violate any rights guaranteed by any Constitution to any individual. It deals with the defendant, not as an individual, but as an employee, official or public servant, paid by the State, and therefore under instructions from the State.... It need hardly be added that this law did not have its origin in bigotry. It is not trying to force any form of religion on anybody. The majority is not trying to establish a religion or to teach it - it is trying to protect itself from the effort of an insolent minority to force irrellgion upon the children under the guise of teaching science."

Bryan went on to argue: "Evolution is not truth; it is merely a hypothesis - it is millions of guesses strung together. It had not been proven in the days of Darwin - he expressed astonishment that with two or three million species it had been impossible to trace any species to any other species - it had not been proven in the days of Huxley, and it has not been proven up to today. It is less than four years ago that Professor Bateson came all the way from London to Canada to tell the American scientists that every effort to trace one species to another had failed - every one. He said he still had faith in evolution but had doubts about the origin of species. But of what value is evolution if it cannot explain the origin of species? While many scientists accept evolution as if it were a fact, they all admit, when questioned, that no explanation has been found as to how one species developed into another." John T. Scopes was found guilty, but soon after the trial, William Jennings Bryan fell ill and died on 26th July, 1925.

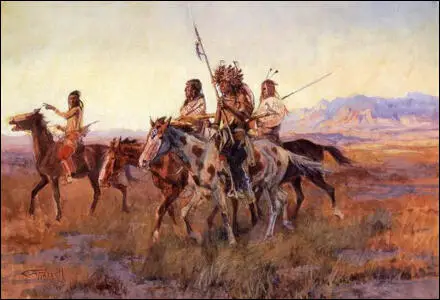

On this day in 1864 Charles Marion Russell was born in Missouri. He left school at 16 and worked as a cowboy and as a fur-trapper. In 1888 he spent six months living with the Blackfoot Indians.

A self-taught artist, his drawings of cowboys and Native Americans were accepted by several specialist magazines such as Recreation, Western Field, Sports Afield and Outing.

As his reputation grew, his illustrations were commissioned by magazines such as Scribner's Magazine, McClures Magazine and the Saturday Evening Post.

Charles Marion Russell died in 1926.

On this day in 1881 Edith Nourse Rogers was born in Saco, Maine. In 1907 she married John Jacob Rogers. The couple were members of the Republican Party. In 1912 Rogers won a seat in Congress in 1912 and they moved to Washington, D.C.

She worked as a volunteer Red Cross worker during the First World War. After the war she became the presidential representative in charge of assisting disabled veterans under Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover.

After the death of John Jacob Rogers in March 1925, Rogers ran for his congressional seat, and in June 1925 she won the special election with 72 percent of the vote.

In Congress she fought for an end to child labour, the 48 hour week and equal pay for women. During the Second World War Rogers introduced legislation to establish the Women's Army Corps.

In 1947, she became the leading Republican Party member of the Committee on Veterans' Affairs and served as its chair for two years. Rogers was a leading advocate of the G.I. Bill of Rights, which gave returning veterans the opportunity to go to college and to receive low-interest loans to buy houses.

Edith Nourse Rogers died on 10th September 1960.

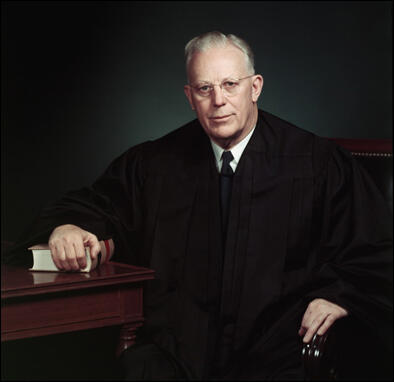

On this day in 1891 Earl Warren, the son of an Norwegian immigrant who worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad, was born in Los Angeles, California, on 19th March, 1891.

Warren obtained a law degree from the University of California in 1912. He worked as a lawyer in California before being elected as district attorney of Alameda County in 1925.

In November 1938 Culbert Olsen was elected as Governor of California, the first member of the Democratic Party, to hold this office for forty-four years. The following year, Warren, a member of the Republican Party, was appointed California's attorney general.

One of Olsen's first acts was to pardon Tom Mooney, a trade union leader who had been convicted of a bombing which occurred in San Francisco in 1916. Although strong evidence existed that the District Attorney of the time, Charles Fickert, had framed Mooney, the Republican governors during this period refused to order his release. In October 1939, Olsen pardoned Warren Billings, a friend of Mooney's who had also been imprisoned for the bombing.

Warren had disagreed with Olsen's actions. As a member of the state Judicial Qualifications Commission, he blocked confirmation of the Olsen's nominee to the state Supreme Court, Max Radin, a man he considered to be too radical for this post.

Warren also upset liberals and supporters of human rights by the role he played in dealing with people of Japanese descent during the Second World War. Most of these people lived in California. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, these people were classified as enemy aliens. Warren, as attorney general, urged that these people should be interned.

On 29th January 1942, the U.S. Attorney General, Francis Biddle, established a number of security areas on the West Coast in California. He also announced that all enemy aliens should be removed from these security areas. Three weeks later President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the construction of relocation camps for Japanese Americans being moved from their homes.

Over the next few months ten permanent camps were constructed to house more than 110,000 Japanese Americans that had been removed from security areas. These people were deprived of their homes, their jobs and their constitutional and legal rights. Warren later confessed: "I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens. Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken."

Warren's extreme views on internment was popular with most people in California and this enabled him to defeat Culbert Olsen as governor in 1943. He held the post for the next ten years. He was also selected as running-mate for Thomas Dewey in 1948. However, Dewey was defeated by Harry S. Truman in the election.

Warren hoped to become the Republican Party's candidate in the 1952 presidential election. He lost out to Dwight D. Eisenhower who went on to become president. Warren was rewarded for his loyalty by being appointed by Eisenhower to the post of chief justice of Supreme Court.

Over the next few years Warren made it clear he supported the civil rights campaign and voted for the banning segregation in America's schools. He now became a target of right-wing groups and Robert Welch, the leader of the John Birch Society, described Warren as being a member of a Communist conspiracy. Other white supremacists such as George Wallace and James Eastland joined in these attacks. At one rally in Los Angeles there were calls for Warren to be lynched.

After the death of John F. Kennedy in 1963 his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." Johnson asked Warren if he would be willing to head the commission. Warren refused but it was later revealled that Johnson blackmailed him into accepting the post. In a telephone conversation with Richard B. Russell Johnson claimed: " Warren told me he wouldn't do it under any circumstances... I called him and ordered him down here and told me no twice and I just pulled out what Hoover told me about a little incident in Mexico City... And he started crying and said, well I won't turn you down... I'll do whatever you say."

Other members of the commission included Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs.

The Warren Commission reported to President Johnson ten months later. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the US Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone.

In 1966 Warren made another landmark decision when he ruled that criminal suspects be informed of their rights before being questioned by the police.

Earl Warren retired from the Supreme Court in 1969, and died on 9th July 1974.

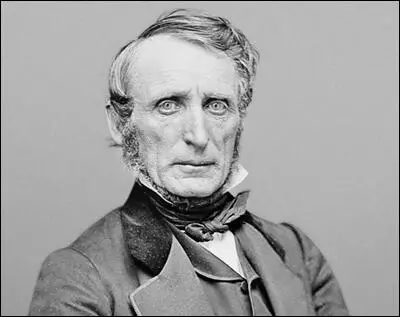

On this day in 1900 John Bingham died in Cadiz, Ohio. John Bingham was born in Mercer, Pennsylvania, on 21st January, 1815. He worked in a printing office for two years before attending Franklin College, Ohio. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. Bingham worked as a lawyer in New Philadelphia, Ohio, before becoming the district attorney for Tuscarawas County (1846-49).

Bingham joined the Republican Party and was elected to the 34th Congress and served between March, 1855 to March 1863. An opponent of slavery, he said after the Battle of Bull Run that: "we need these reverses to bring our people up to the peril of not abolishing slavery."

An unsuccessful candidate for the 38th Congress, Abraham Lincoln decided in 1864 to appoint him as judge advocate of the Union Army. After the assassination of Lincoln, Andrew Johnson ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the suspected conspirators. It was argued by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, that the men should be tried by a military court as Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the United States Army.

As Judge Advocate of the Union Army, Bingham, along with Joseph Holt, the Advocate General, had the task of helping present the government case against Mary Surratt, Lewis Paine, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold.

The trial began on 10th May, 1865. The military commission included leading generals such as David Hunter, Lewis Wallace, Robert Foster, August Kautz, Thomas Harris and Albion Howe.

John Bingham and Joseph Holt attempted to obscure the fact that there were two plots: the first to kidnap and the second to assassinate. It was important for the prosecution not to reveal the existence of a diary taken from the body of John Wilkes Booth. The diary made it clear that the assassination plan dated from 14th April. The defence surprisingly did not call for Booth's diary to be produced in court.

On 29th June, 1865 Mary Surratt, Lewis Paine, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. Surratt, Paine, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Surratt, who was expected to be reprieved, was the first woman in American history to be executed.

Bingham was elected to the 39th Congress and over the next couple of years became one of the leading opponents of the new president, Andrew Johnson. A strong opponent of slavery, Bingham, like many people in the Republican Party, objected to Johnson's attempts to veto the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. Bingham played an important role in the impeachment of Johnson and gave the closing, three-day summation.

In 1873 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Bingham as his minister to Japan. He served in the post for twelve years and did not return to live in the United States until 1885.

On this day in 1905 Albert Speer, the son of an architect, was born in Mannheim. After studying architecture at the Munich Institute of Technology and at the Berlin-Charlottenburg Institute, he became an architect in 1927.

In 1931 Speer joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) and the following year he became a member of the Schutz Staffeinel (SS). He later admitted: "In making this decision to join the accursed party, I had for the first time denied my own past, my upper-middle-class origins, and my previous environment. My inclination to be relieved of having to think, particularly about unpleasant facts, helped to sway the balance. In this I did not differ from millions of others. Such mental slackness above all facilitated, established, and finally assured the success of the National Socialist system. And I thought that by paying my party dues of a few marks a month I had settled with my political obligations."

The historian, Ulf Schmidt, has pointed out in his book, Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor (2007) that Speer was a close friend of Karl Brandt: "One of Karl Brandt's closest friends was Albert Speer, Hitler's personal architect. Both belonged to a generation of young professionals, born between 1900 and 1910, who experienced the First World War as children or adolescents, and later advanced to key executive positions in the regime, a young expert elite (Funktionselite), as Michael Wildt has pointed out, often highly ambitious and competitive, but also with little empathy for the suffering of others."

Speer met Adolf Hitler in July 1933 and gave him the task of organizing the 1934 Nuremberg Rally. Speer admitted that "in those first years I was ready to follow him wherever he led." Louis L. Snyder has argued: "A frustrated architect himself, the Führer saw in Speer a means of fulfilling his own youthful dreams". It has been claimed by Gitta Sereny that the two men were attracted to each other because of their psychological past: "Both were bedevilled from childhood by thwarted, imagined and withheld love, a deficiency which rendered them both virtually incapable of expressing private emotions... Both of them, capable of great charm and courted by women, could barely respond though neither of them was homosexual."

Ronald Hayman has pointed out: "The attractive, well-born, Nordic-looking Speer was a man Hitler would have liked to resemble, or, ideally, to be. Able to transpose Speer's concepts into reality, Hitler was the all-powerful father, the protector Speer had always needed or believed himself to need. Never developing the homosexual side of his nature, Hitler was aware of it and sufficiently afraid of it to hit out viciously against homosexuals and homosexuality, fulminating against it as a social evil he would eradicate as soon as he came to power. And he tried to implement this threat. In Germany there were almost 30,000 prosecutions for homosexuality between 1936 and 1939, compared with 3261 between 1931 and 1934."

In 1937 Albert Speer was appointed as General Architectural Inspector of the Reich, with instructions to "turn Berlin into a real and true capital of the German Reich." This included the Reich Chancellery in Berlin and various buildings in Nuremberg. Speer worked tirelessly to convert Hitler's grandiose words into stone. He designed state offices, stadiums, monuments and cities for Nazi Germany. In 1938 Hitler conferred the party's Golden Badge of Honor on him.

In 1941 Speer was elected a delegate to the Reichstag to represent the Wahlkreis Electoral District. In February, 1942, Adolf Hitler appointed Speer as Minister of Armaments, succeeding Dr. Fritz Todt, who had been killed in an aircraft accident. A good administrator, Speer considerably raised production levels of armaments. Working closely with Karl Doenitz Speer was able to announce that Germany was producing 42 U-boats a month by 1945.

Speer clashed with Heinrich Himmler arguing that concentration camp factories were inefficient and preferred using paid labour in occupied countries. He later claimed that he saved lives because of this policy but his opponents pointed out that this policy had more to do with efficiency than morality. Between 1941 and 1945 he was the virtual dictator of the German war economy.

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary on 27th March, 1945: "Speer is more of an artist by nature. Admittedly he has great organizational talent but politically he is too inexperienced to be totally reliable in this critical time. The Führer is very angry about recent statements made to him by Speer. Speer has allowed himself to be influenced by his industrialists and is continually saying that he does not intend to lift a finger to cut the German people's lifeline; this is for our enemies to do; he does not intend to take responsibility for it. The Führer counters this by saying that we have to carry the responsibility anyway, that the point now is to bring the struggle for our people's existence to a successful conclusion and that tactical questions play only a subordinate role. The Führer intends to summon Speer during the afternoon and face him with a stern alternative: either he must conform to the principles of present-day conduct of the war or the Führer will dispense with his assistance. He says with much bitterness that he would prefer to live in a prefab or creep underground then have palaces built by a member of his staff who had proved a failure at the moment of crisis."

At the end of the Second World War Speer was arrested and was charged with using slave labour in his production programmes. Speer pleaded guilty and was sentenced to twenty five years in prison. The historian, Ulf Schmidt, has pointed out: "Speer was personally involved in the Holocaust, that his ministry provided the building materials for an extension of Auschwitz, that he made a substantial fortune with Aryanized property, denounced uncooperative competitors, initiated the construction of concentration camps, and supported the draconian measures used against forced and slave labourers in some of Germany's most horrific underground production facilities. If only a part of this had been known during the International Military Tribunal in 1945, which preceded the trial against Karl Brandt and others, Speer would probably have been sentenced to death. The fact that most of it was unknown at the time gave Speer the possibility of creating his own carefully constructed, but also greatly biased, post-war narrative of himself and the regime, a convenient and plausible story, which scholars and journalists either took for granted or were unable to refute."

After being released from Spandau Prison in 1966, Speer published his memoirs, Inside the Third Reich (1970) and Spandau: The Secret Diaries (1976). Albert Speer died on 1st September 1981.

On this day in 1910 Lilias Ashworth Hallett planted her suffrage tree. Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary: "Mrs. Ashworth Hallett came with her husband and planted her holly. She was one of the first workers for the suffrage and knew Dr. Pankhurst before he was married, in Manchester, when her Uncle Jacob Bright was there.... Mrs. Hallett quite thanked us for helping the Suffragettes, but like ourselves they do not like violent methods." Mary Blathwayt wrote in her diary that Mrs. Ashworth Hallett told her that the "militant methods of the Suffragettes... made her quite ill."

Lilias Ashworth, the daughter of Thomas Ashworth and Sophia Bright, was born in 1844. Her mother was the sister of Jacob Bright, Priscilla Bright McLaren and Margaret Bright Lucas.

Ashworth was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and signed a petition organized by the Enfranchisement of Women Committee and joined the London Society for Women's Suffrage in 1867. The following year she was present at the first public meeting of the Manchester National Society. Over the next few months she became a close friend of fellow members, Lydia Becker and Richard Pankhurst.

According toElizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She was herself a valuable and busy speaker for the suffrage cause. It required considerable courage then for a woman to sit on a public platform and actually to speak from one was regarded as almost indecent." Ashworth later recalled that "when we appeared in our quiet black dresses it was amusing to note the sudden change in the faces of the crowd who had come to look at us." Over the next few years she developed a reputation as one of the best public speakers on the subject of women's suffrage. William Waldegrave Palmer compared her to Jacob Bright when he said "she possesses the oratorical power of her uncle, both for argument, pathos and satire."

In November 1871, Jacob Bright suggested at the annual general meeting of the Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage that greater pressure could be applied on members of the House of Commons by establishing a Central Society for Women's Suffrage in London. The first meeting of this new group was held on 17th January 1872. The first executive committee included Lilias Ashworth, Frances Power Cobbe, Priscilla Bright McLaren and Agnes Garrett.

The following year Lilias Ashworth became a member of Married Women's Property Committee. After the death of her parents she became a wealthy woman and donated large sums of money to women's suffrage pressure groups. This included a £100 donation to the Central Society in 1873.

At a Quaker ceremony in 1877 Lilias Ashworth married Professor Thomas Hallett of Bristol University. He had been active in the Liberal Party and had written pamphlets on Free Trade and Ireland. Her uncle, Jacob Bright, commented in the Women's Suffrage Journal that the family believed "that the homes where women were politically instructed, were happier homes than those where women were politically ignorant." The couple had no children.

Lilias Ashworth Hallett remained committed to the campaign for the vote. She was convinced that it was only a matter of time before Parliament agreed to their demands. She argued, "Women have become necessary to the success of party organizations, and to deny them the power of quietly going into a polling booth to record a vote is no longer rationally possible.

In 1903 she became a member of the executive committee of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. She was also vice-president of the Central Society for Women's Suffrage and a member of the London Society for Women's Suffrage.

Hallett became disillusioned with the lack of success achieved by the various constitutional suffrage societies and she was initially sympathetic to the actions of the militant Women Social & Political Union. In 1906 she joined with Millicent Fawcett in organizing the banquet at the Savoy to celebrate the release from Holloway Prison of WSPU prisoners.

On 13th February 1907 she joined the march from the Women's Parliament in Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. The following day The Times published her letter which gave an account of her first WSPU demonstration: "My astonishment was great when I found we were suddenly encompassed by police on foot and horse-back, and our courage rose in proportion to the indignation we felt. Police blocked the footway. They laughed and jeered... I was twice arrested." Hallett admitted that she was released when she told the policeman who held her that she would report them to her friends in Parliament. She added: "They were not sure who I might be. If I had seemed more like a Lancashire mill-hand, I should doubtless be in Holloway this morning."

As a result of this experience Lilias Ashworth Hallett became a financial supporter of the WSPU. In 1907 she gave £75 and the following year she increased her donation to £90. Mary Blathwayt noted that when Hallett attended a NUWSS meeting in Bath in 1908 she wore a WSPU badge.

Hallett was also a regular visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston. Colonel Linley Blathwayt and his wife, Emily Blathwayt, were both supporters of the WSPU. In May 1908 she chaired a WSPU meeting at Eagle House, where Annie Kenney was the principal speaker. Colonel Blathwayt decided to create a suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. The idea was for women to be invited to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes.

Over the next few months Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Mary Phillips, Vera Holme, Jessie Kenney, Georgina Brackenbury, Marie Brackenbury, Aeta Lamb, Theresa Garnett, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Adela Pankhurst, Marion Wallace-Dunlop, Vera Wentworth and Elsie Howey also took part in this ceremony. Eventually, even women who had not been to prison, such as Mrs. Ashworth Hallett and Millicent Fawcett planted trees. She eventually broke with the WSPU when they began their arson campaign in 1912.

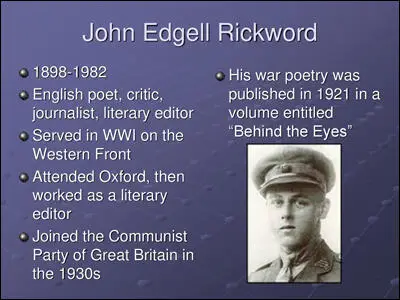

On this day in 1918 Edgell Rickword was seriously wounded on the Western Front. John Edgell Rickword was born in Colchester on 22nd October, 1898. His father, George Rickword, was the borough librarian. He attended Colchester Royal Grammar School. As a teenager he was converted to socialism by reading the works of William Morris, Jack London, Frank Norris, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells.

On the outbreak of the First World War Rickword was only 16 years old. He therefore had to wait until September 1916 before he could join the Artists' Rifles. Other members of the regiment included Charles Jagger, Bert Thomas, Robert Sherriffs, Barnes Wallis, Edward Thomas, Paul Nash, John Nash and John Lavery.

Rickword later recalled that the decision to join the British Army reflected "our state of mind" at the time. "We were inured to colonial wars, pacifications of backward peoples (our toy soldiers had signiificantly light armaments), which only differed from the more risky and expensive forms of sport in the degree of danger and hardship involved."

After training at Hare Hall Camp in Guidea Park. As his biographer, Charles Hobday, points out: "Having learnt the rudiments of military drill in his school cadet corps, he found some of the training course easy, though boring, but as he was not deft with his hands the winding of his puttees and the folding of his blankets to meet the army's standards of neatness were something of a nightmare."

In December 1917, Rickword was gazetted to the 5th Battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He did not reach the Western Front until 21st January 1918. His stay on the front-line at Fleurbaix lasted only seven days and the battalion's official war diary records that their was little action with only two men receiving wounds that week.

Rickword returned to the front-line and during February the German Army gradually increased its shelling of the area. On 19th March, Rickword and James Rowe, were put in charge of a working party and during their duties, a shell exploded nearby. Rowe was killed and Rickword suffered a wound to the soldier and was able to rejoin his regiment on 24th March. He later wrote: "It was not the suffering and slaughter in themselves that were unbearable, it was the absence of any conviction that they were necessary, that they were leading to a better organization of society."

On 12th May 1918, Rickword was again wounded. This time his injuries were bad enough to be sent to a military hospital in Reading. After recovering his health he arrived back in France in September, 1918. The following month his regiment was deployed to Vimy Ridge. On 14th October he volunteered to swim across the Haute Deule Canal in order to reconnaissance German positions. This information enabled his regiment to take three villages in the area, Malmaison, Leforest and Cordela, and was part of the advance that forced Germany to retreat.

Rickword later wrote: "Our rulers were not war-weary, but the ordinary people who were suffering on the home and battle fronts were thinking: Not another winter of this! I know that was the feeling among the troops in Flanders in October 1918." The following month the Armistice was signed.

On 4th January 1919, Rickword developed an illness that was diagnosed as a "general vascular invasion which had resulted in general septicaemia". His left eye was so badly infected that they thought it necessary to remove it to prevent the infection from spreading to the other eye. As Charles Hobday points out: the infected eye was removed and replaced by a glass one (for which he was charged three guineas), and the other remained in working order for nearly sixty years, although with impaired vision."

Edgell Rickword went up to Pembroke College in September 1919. Over the next few months he met the poets Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Roy Campbell, L. P. Hartley, Louis Golding, A. E. Coppard and Edmund Blunden. Sassoon was at that time literary editor of The Daily Herald and he helped Rickword get some of his poems published. This included Winter Warfare in the weekly Land and Water.

In November 1919 Rickword became the lover of an Irish woman named Margaret McGrath. It inspired Intimacy, according to Charles Hobday "one of the great English love poems of the twentieth century". Rickword's poems appeared in Oxford Poetry (1920). The book also included the poems of other students such as Roy Campbell, Robert Graves, L. P. Hartley, Edmund Blunden and Louis Golding. His collected early verse appeared in Behind the Eyes (1921).

In 1921 Rickword met Douglas Garman through Roy Campbell, the husband of his sister Mary Garman. As Cressida Connolly has pointed out: "He (Rickword) was slight and fair-haired, with a very quiet manner and a soft voice. His post-war lyrics - the erotic poems in particular - show a debt to Donne and the metaphysical poets as well as to Baudelaire and the symbolists."

Rickword's friend, Edward Wishart, established a new publishing house, Wishart & Company, after leaving university. Rickword went to work for the company and with Douglas Garman, published a quarterly literary review, Calendar of Modern Letters from March 1925. It included the work of Robert Graves, E. M. Forster, Aldous Huxley, A. E. Coppard, L. P. Hartley, Cecil Gray, Hart Crane, T. F. Powys, Allen Tate, Roy Campbell, John Holms, Edmund Blunden, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Siegfried Sassoon, D. H. Lawrence, Bertrand Russell and Edwin Muir.

In 1926 Rickword decided to move to Penybont to live with his girlfriend, Thomasina, and Douglas Garman and his new wife, Jeanne Hewitt. Both men were socialists and later that year attempted to support the miners during the General Strike. Rickword was very disappointed when the Trade Union Congress called off the strike.

Rickword continued to edit Calendar of Modern Letters. However, the journal folded in 1927 but Ernest Wishart made sure that there was other editorial work to do for his company.

For many years Rickword had been a member of the Labour Party. However, in 1934, he decided to join the Communist Party of Great Britain. His two closest friends, Ernest Wishart and Douglas Garman, also joined. Along with Randall Swingler and Jack Lindsay he was considered as one of the most important intellectuals in the party.

Early in 1934 a meeting was held of the British section of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers. Among those present included Rickword, Tom Wintringham, Ralph Fox, John Strachey, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Montagu Slater, A.L. Lloyd, Hugh MacDiarmid and Amabel Williams-Ellis. This meeting decided to publish a new Marxist journal. The Left Review first appeared in October 1934. Contributors to the journal included A. L. Morton, Nancy Cunard, F. D. Kingender, Valentine Ackland, W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Edward Upward, Cecil Day-Lewis, Storm Jameson, Randall Swingler, Jack Lindsay, Margaret Storm Jameson, Naomi Mitchison, Winifred Holtby, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Eric Gill, Herbert Read and George Barker.

In 1934 Edgell Rickword persuaded Ernest Wishart and Douglas Garman to publish Negro, an anthology of pieces by 150 writers on black politics and culture, collected and edited by Nancy Cunard. As Edgell Rickword said later: "We all three felt to some degree that literature must be understood and practised as a part of a culture wider and deeper than any single art form, because culture was the essence of the way in which people lived and thought and felt."

In 1935 Ernest Wishart merged his company with another publishing house to form Lawrence and Wishart. The new company moved to offices in Red Lion Square and became the press of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Roy Campbell and Mary Campbell went to stay with Ernest Wishart and Lorna Wishart in December 1937. The Wisharts organised a dinner party that including Rickword, Peggy Guggenheim and Douglas Garman. A discussion on the Spanish Civil War caused a major rift in the family. Rickword later commented: "He (Campbell) was very good fun, by no means a fool. But where he got this crappy, hysterical sort of fascism from, I don't know." Campbell responded by describing Wishart's home as "Bolshevik Binsted".

During the Second World War Rickword became editor of Our Time. For the next three years he published the work of Christopher Hill, Charles Hobday, Mervyn Jones, Jack Lindsay, David Holbrook, Randall Swingler, E. P. Thompson and Doris Lessing.

Edgell Rickword died on 15th March, 1982.

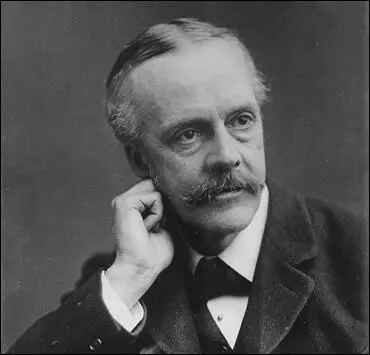

On this day in 1930 Arthur Balfour died. Arthur Balfour was born on the family's Scottish estate in East Lothian on 25th July 1848. Educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, he entered the House of Commons in 1874 as the Conservative MP for Hertford.

In 1878 Balfour became private secretary to his uncle, the Marquess of Salisbury, who was Foreign Secretary in the Conservative government headed by Benjamin Disraeli.

In the 1885 General Election Balfour was elected to represent the East Manchester constituency. The Marquess of Salisbury, who was now Prime Minister, appointed him as his Secretary for Scotland. Other posts during the next few years included Chief Secretary of Ireland (1887), First Lord of the Treasury (1892) and leader of the House of Commons (1892).

Balfour replaced his uncle as Prime Minister in 1902. The most important events during his premiership included the 1902 Education Act and the ending of the Boer War. The topic of Tariff Reform split Balfour's government and when he resigned in 1905, Edward VII invited Henry Campbell-Bannerman to form a government. Campbell-Bannerman accepted and in the 1906 General Election that followed the Liberal Party had a landslide victory.

Balfour remained leader of the Conservative Party until he was replaced by Andrew Bonar Law in 1911. He returned to government when in 1915 Herbert Asquith offered him the post of First Lord of the Admiralty in Britain's First World War coalition government. The following year, David Lloyd George, the new Prime Minister, appointed him as Foreign Secretary, and consequently was responsible for the Balfour Declaration in 1917 which promised Zionists a national home in Palestine.

Henry Hamilton Fyfe, who worked for The Times reported: "I saw that Balfour was not a great man. He had charm and wit; he could be energetic when he chose, but he chose very seldom; he had a marvellously acute mind, but he feared the logic of its conclusions. He was truly bored by almost everything, and he was born lazy. I recall one of his official secretaries telling me furiously how Balfour was primed for a critical debate, given sheaves of notes, told what his line of argument must be. And then, spluttered Robert Morant, he stuffed all the papers in his pocket without looking at them, and made a speech that missed all the essential points. After such episodes he would be more than usually charming, and would ask with a smile and a slight lift of his shoulders, What does it matter?"

Balfour left Lloyd George's government in 1919 but returned to office when he served as Lord President of the Council (1925-29) in the Conservative government headed by Stanley Baldwin.

On this day in 1939 for the first time The Times. the most consistent supporter of appeasement among in the national press, suggested that "German policy no longer seeks the protection of a moral case" and urged a policy of close co-operation with other nations to resist Adolf Hitler. Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail, did not have these concerns. In a letter intercepted by the British intelligence services Rothermere congratulated Hitler "on his walk into Prague" and urged him to invade Romania.

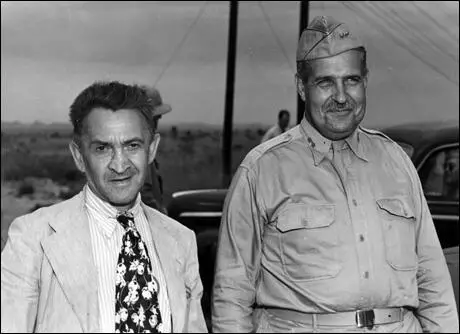

Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden, encouraging the growth of fascism (c. 1938)

On this day in 1977 William Laurence died died in Majorca. William Laurence was born in Lithuania in 1888. As a young man he developed radical political opinions and in 1905 he was forced to flee from Russia. Laurence moved to the United States and eventually became a science reporter for several leading newspapers and magazines in the country.

Laurence had the ability to translate the complexities of modern science into articles that could be understood by the general public. He had good contacts with the world's leading scientists and in 1940 began writing articles about nuclear research for the New York Times and the Saturday Evening Post. Laurence argued that in future small quantities of U-235, would propel an ocean liner, heat and light entire cities and set off a destructive bomb blast that was equivalent of twenty thousand tons of TNT.

After Pearl Harbor Laurence noticed that scientists in the United States working in this field began to refuse to talk to him. He became convinced that the Allies were involved in a secret atom bomb project. This was confirmed in the summer of 1942 when the United States Office of Censorship wrote to him asking him not to write articles on the potential of nuclear power.

In April 1945 Laurence was contacted by General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project. Groves told Laurence about the project and recruited him to become the official chronicler of the development of the atom bomb. For the next three months he was allowed to interview the scientists working on the project and prepare the press releases needed when this new weapon was used.

Laurence witnessed the first test explosion of an atomic bomb in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico. He also interviewed the crew that took part in the raid on Hiroshima and was on the plane that dropped the atom bomb on Nagasaki.

Articles published by Laurence in the New York Times in 1945 won him the Pulitzer Prize. He was employed as Science Editor of the newspaper between 1956 and 1964.