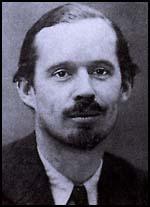

John Holms

John Holms, the son of the governor-general of the United Provinces of India, was born in 1897. When he was a young child he was sent to boarding school in England. His father wanted him to enter the diplomatic service but instead he became a student at Sandhurst Military College.

He joined the British Army on the outbreak of the First World War. He was sent to the Western Front. According to Peggy Guggenheim "he was strong as a bull and had killed four Germans by hammering them on the head when he had surprised them breakfasting under a tree." For this action he won the Military Cross.

Holms took part in the Somme offensive but while on night patrol in March 1918 he was captured by the German Army. He spent the next seven months in a prison camp in Mainz. Fellow prisoners included Alec Waugh, Hugh Kingsmill and John Milton Hayes. The author, Mary Dearborn, has argued: "Surrounded by a high barbed-wire fence guarded by sentries, the men, students of what Waugh called the University of Mainz, had no duties or jobs and spent most of their days, armed with paper and pen and books, in a narrow book-lined room off the dinning-hall."

After the war he attempted to become a full-time writer. Ernest Wishart, Douglas Garman and Edgell Rickword liked his work and his stories and book reviews appeared in their quarterly literary review, Calendar of Modern Letters. However, he was not very productive. His friend, Alec Waugh, commented: "He was how I expected a genius to look after he found his medium."

In 1919 Holms met Dorothy Peacock, a woman who was seven years older than him. They fell in love and although they did not marry, she became known as Dorothy Holms. Over the next eight years they lived all over Europe including St. Tropez, Salzburg, Dresden, Zagreb and Paris. A friend said that Dorothy complained that living with Holms was like being a "governess to a baby".

While visiting Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, in 1928 they met Peggy Guggenheim and her husband, Laurence Vail. Peggy later recalled: "When I first met John Holms I was impressed by his elastic quality. Physically, he seemed barely to be knit together. You felt as if he might fall apart anywhere. When you danced with him it was even more apparent, because he could move every muscle of his body without its being noticeable and without the usual jerks one suffers in such cases. He was very tall, over six feet in height. He hail a magnificent physique, enormous broad shoulders and small hips and a fine chest. He wore a small red beard and looked very much like Jesus Christ. His hair was wavy, thick and auburn red. His skin was white, but from the southern sun it had turned pink. His eyes were deep brown and he wore glasses; he had a classical straight nose. His mouth was small and sensuous and seemed to be pursed up under his moustache."

Peggy Guggenheim admitted in her autobiography, Out of this Century (1979): "all I remember now is that he took me to a tower and kissed me... that certainly made an impression on me, and I can attribute everything that followed to that simple little kiss." Guggenheim invited the Holmses to visit her home in Pramousquier. "They came overnight and we went in bathing at midnight, quite naked. John and I found ourselves alone on the beach and we made love."

John Holms left Dorothy and he went to live with Peggy who had moved out of her family home. Peggy wrote in her autobiography: "It seems to me that John Holms and I did nothing but travel for two years. We must have gone to at least twenty countries and covered ten million miles of ground."

Edwin Muir, who was a close friend, argued: "John Holms was the most remarkable man I ever met. His mind had a majestic clarity and order... Though his sole ambition was to be a writer, the mere act of writing was another enormous obstacle to him: it was as if the technique of action were beyond his grasp, a simple, banal, but incomprehensible mystery. He knew his weakness, and it filled him with the fear that, in spite of the gifts which he knew he had, he would never be able to express them; the knowledge and the fear finally reached a stationary condition and reduced him to impotence."

Peggy Guggenheim agreed that Holms had the potential to be a great writer: "Since no one else shared his extraordinary mental capacity, he was exceedingly bored when talking to most people. As a result, he was very lonely. He knew what gifts he had and felt wicked for not using them. Not being able to write, he was unhappy, which caused him to drink more and more. All the time that I was with him I was shocked by his paralysis of will power. It seemed to grow steadily, and in the end he could hardly force himself to do the simplest things." Peggy had to admit: "John had written only one poem in all the years he was with me. I had done nothing but complain about his indolent life."

Emma Goldman said in January 1929: "The main trouble is that John (Holms) is weak and ineffectual, a drifter unable to make one single decisive step. He wants to eat the pie and keep it at the same time." Emily Coleman added that his "incapacity to shoulder responsibility through some inexplicable paralysis of the will." William Gerhardie said of Holms: "In every age... there are men who while achieving nothing give an impression of greater genius than the acknowledged masters of the day."

In March 1933 John and Peggy met Douglas Garman, who was a director of Lawrence and Wishart, in the Chandos pub in Trafalgar Square, about publishing Ryder, a novel written by his friend, Djuna Barnes. In her autobiography, Out of this Century (1979), Guggenheim commented: "Douglas Garman never published Ryder. I believe he did not like it, but he asked us if he could come to stay with us in Paris at Easter time. When he came, I fell in love with him." However, she continued to live with Holms.

That summer John Holms fractured his wrist, riding on Dartmoor with Peggy. Despite being reset, the bones had never realigned correctly, and he had been advised to have a simple operation. Holms was a heavy drinker and on the morning of the operation on 19th January, 1934, he had a terrible hangover. Holms died under the anaesthetic. After his death Peggy and Douglas Garman set up home at Yew Tree Cottage in South Harting.

Primary Sources

(1) Peggy Guggenheim, Out of the Century (1979)

When I first met John Holms I was impressed by his elastic quality. Physically, he seemed barely to be knit together. You felt as if he might fall apart anywhere. When you danced with him it was even more apparent, because he could move every muscle of his body without its being noticeable and without the usual jerks one suffers in such cases. He was very tall, over six feet in height. He hail a magnificent physique, enormous broad shoulders and small hips and a fine chest. He wore a small red beard and looked very much like Jesus Christ. His hair was wavy, thick and auburn red. His skin was white, but from the southern sun it had turned pink. His eyes were deep brown and he wore glasses; he had a classical straight nose. His mouth was small and sensuous and seemed to be pursed up under his moustache...

He rarely saw his family, who were living in retirement at Cheltenham. He found all contact with them difficult because he belonged to a different world. He knew much too much about theirs, and they knew much too little about his. His father had wanted him to enter the diplomatic service, but when the war broke out he was a student at Sandhurst Military College and joined up at the age of seventeen. At that time, he was as strong as a bull and had killed four Germans by hammering them on the head when he had surprised them breakfasting under a tree. For this, to his great shame, he was given the Military Cross. After six months of war on the Somme in the light infantry, he had been taken prisoner in a night patrol, and had spent the rest of the war (two years) in a German prison camp. In prison he met Hugh Kingsmill, who became a lifelong friend. His other great friend was Edwin Muir.

In the prison, because he was an officer, he had been pretty well treated and was unfortunately allowed to have all the liquor he wanted to buy. This undoubtedly had done him much harm, for his capacity for drink was greater than anyone's I have ever known. He drank about five drinks to other people's one and yet he never seemed to be affected by it until about three in the morning when he looked peculiar, with his eyes half shutting. However, he never behaved badly in any way. Drink made him talk, and he talked like Socrates. All his varied education and knowledge of people and life, which should have been expressed in writing, came out in conversation. lie held people spellbound for hours. He seemed to have everything at his fingertips, as though he had been in contact with everything, had seen everything and thought about everything. He was like a very old soul that nothing could surprise. This gave him a detached quality and I was greatly astonished much later when I discovered what passion lurked under this indifferent exterior. I always thought of him as a ghost. He was definitely a frustrated writer, although at one period in his life he had had a great success in London writing criticism, and he still received letters begging him to write articles. He could not get himself to write at all any more. And though he needed money very badly because he received only a meager allowance from his father, he preferred to live in the greatest simplicity at St. Tropez rather than go back to England.

(2) Edwin Muir, An Autobiography (1954)

John Holms was the most remarkable man I ever met. His mind had a majestic clarity and order... Though his sole ambition was to be a writer, the mere act of writing was another enormous obstacle to him: it was as if the technique of action were beyond his grasp, a simple, banal, but incomprehensible mystery. He knew his weakness, and it filled him with the fear that, in spite of the gifts which he knew he had, he would never be able to express them; the knowledge and the fear finally reached a stationary condition and reduced him to impotence.

(3) Mary Dearborn, Peggy Guggenheim: Mistress of Modernism (2004)

Physical descriptions of John Holms vary as well. He had a short pointed beard; to Alec Waugh's eyes, he "looked like a Spanish grandee," and Waugh added, "People stared at him when he came into a room." Peggy noted his "elastic quality" and his resemblance to images of Jesus Christ, something other observers mentioned too. Muir described him as "tall and lean, with a fine Elizabethan brow and auburn, curly hair, brown eyes with an animal sadness in them, a large, somewhat sensual mouth, and a little pointed beard which he twirled when he was searching for a word." Muir noted that his friend was known as a fine athlete at Rugby, but commented on his somewhat odd physical presence: "In his movements he was like a powerful cat; he loved... trees or anything that could be climbed, and he had all sorts of odd accomplishments: he could scuttle along on all fours at a great speed without bending his knees; walking, on the other hand, bored him. He had the immobility of a cat too, and could sit for long stretches without stirring." Several observers noted a generally unkempt Holms; Waugh said that by 1919 he "was wearing pre-war shabby clothes," noting also, however, "he wore them with an air." When Holms visited William Gerhardie in London in the thirties, he arrived in a Rolls-Royce, but he wore "a very old soiled mackintosh." Gerhardie, who would directly portray Peggy and John in his 1936 novel Of Mortal Love, continued, "We went for a long drive together, and the immaculate chauffeur took his peremptory orders from his red-bearded, dilapidated, shabby master with faint distaste." Peggy, however, notes in her memoirs that she converted him to dressing well, sending him to London tailors.

Women did not always see John Holms in a charitable light. Edwin Muir's wife, Willa, in her memoirs, recalls a man who ignored her presence and talked only to her husband, and who questioned her housekeeping; she complains about "Holms's monopolizing personality." Eventually she told her husband she would "rather die than sit at the same table with (Holms) again."

(4) Peggy Guggenheim, Out of the Century (1979)

When I first met John, not only was I ignorant of all human motives, but, worst of all, completely ignorant of myself. I lived in a repressed, unconscious world. In five years he taught me what life was all about. He interpreted my dreams and analyzed me and made me realize that I was good and evil, and made me overcome the evil.

John not only loved women: he understood them. lie knew what they felt. He always said, "Poor women," as though he meant they deserved extra pity for being born of the wrong sex. He was so conscious of everybody's thoughts that it was painful for him to be in a room with discordant elements. Therefore he was supremely careful whom he chose to invite together. He had a wonderful gift of bringing out people's best qualities. He spent most of his time reading, and his criticism was of a quality that I had never before encountered. He was a great help to his writer friends, who accepted his opinions and criticisms without reserve. He never took anything for granted. He saw the underlying meanings of everything. He knew why everybody wrote as they did, made the kind of films they made or painted the kind of pictures they painted. To be in his company was equivalent to living in sort of undreamed of fifth dimension. It had never occurred to me that the things he thought about existed. He was the only person I have ever met who could give me a satisfactory reply to any question. He never said, "I don't know." He always did know. Since no one else shared his extraordinary mental capacity, he was exceedingly bored when talking to most people. As a result, he was very lonely. He knew what gifts he had and felt wicked for not using them. Not being able to write, he was ' unhappy, which caused him to drink more and more. All the time that I was with him I was shocked by his paralysis of will power. It seemed to grow steadily, and in the end he could hardly force himself to do the simplest things.