Marriage in the 19th Century

In the 19th century Britain women were expected to marry and have children. However, there was in fact a shortage of available men. Census figures for the period reveal there were far more women than men. There were three main reasons why women outnumbered men. The mortality rate for boys was far higher than for girls; a large number of males served in the armed forces abroad and men were more likely to emigrate than women. By 1861 there were 10,380,285 women living in England and Wales but only 9,825,246 men.

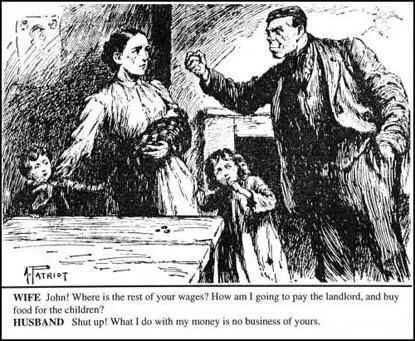

The laws in Britain were based on the idea that women would get married and that their husbands would take care of them. Before the passing of the 1882 Married Property Act, when a woman got married her wealth was passed to her husband. If a woman worked after marriage, her earnings also belonged to her husband.

The idea was that upper and middle class women had to stay dependent on a man: first as a daughter and later as a wife. Once married, it was extremely difficult for a woman to obtain a divorce. The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 gave men the right to divorce their wives on the grounds of adultery. However, married women were not able to obtain a divorce if they discovered that their husbands had been unfaithful. Once divorced, the children became the man's property and the mother could be prevented from seeing her children.

by the Women's Freedom League (February, 1911)

Primary Sources

(1) In 1854 Caroline Norton gave an account of how her husband beat her during her marriage.

We had been married about two months, when, one evening, after we had all withdrawn to our apartments, we were discussing some opinion Mr. Norton had expressed; I said, that "I thought I had never heard so silly or ridiculous a conclusion." This remark was punished by a sudden and violent kick; the blow reached my side; it caused great pain for several days, and being afraid to remain with him, I sat up the whole night in another apartment.

Four or five months afterwards, when we were settled in London, we had returned home from a ball; I had then no personal dispute with Mr. Norton, but he indulged in bitter and coarse remarks respecting a young relative of mine, who, though married, continued to dance - a practice, Mr. Norton said, no husband ought to permit. I defended the lady spoken of when he suddenly sprang from the bed, seized me by the nape of the neck, and dashed me down on the floor. The sound of my fall woke my sister and brother-in-law, who slept in a room below, and they ran up to the door. Mr. Norton locked it, and stood over me, declaring no one should enter. I could not speak - I only moaned. My brother-in-law burst the door open and carried me downstairs. I had a swelling on my head for many days afterwards.

(2) In 1852 Florence Nightingale wrote Cassandra but on the advice of friends she never published the book.

Women are never supposed to have any occupation of sufficient importance not to be interrupted, except "suckling their fools"; and women themselves have accepted this, have written books to support it, and have trained themselves so as to consider whatever they do as not of such value to the world as others, but that they can throw it up at the first "claim of social life". They have accustomed themselves to consider intellectual occupation as a merely selfish amusement, which it is their "duty" to give up for every trifler more selfish than themselves.

Women never have an half-hour in all their lives (except before and after anybody is up in the house) that they can call their own, without fear of offending or of hurting someone. Why do people sit up late, or, more rarely, get up so early? Not because the day is not long enough, but because they have "no time in the day to themselves".

The family? It is too narrow a field for the development of an immortal spirit, be that spirit male or female. The family uses people, not for what they are, not for what they are intended to be, but for what it wants for - its own uses. It thinks of them not as what God has made them, but as the something which it has arranged that they shall be. This system dooms some minds to incurable infancy, others to silent misery.

(3) In her book Women's Suffrage published in 1911, Millicent Garrett Fawcett criticised the passing of the 1857 Divorce Act.

In 1857 the Divorce Act was passed, and, as is well known, set up by law a different moral standard for men and women. Under this Act, which is still in force, a man can obtain the dissolution of the marriage if he can prove one act of infidelity on the part of his wife; but a woman cannot get her marriage dissolved unless she can prove that her husband has been guilty both of infidelity and cruelty.

(4) Charlotte Despard wrote about her feelings as a young woman in the 1850s in a brief, unpublished memoir.

It was a strange time, unsatisfactory, full of ungratified aspirations. I longed ardently to be of some use in the world, but as we were girls with a little money and born into a particular social position, it was not thought necessary that we should do anything but amuse ourselves until the time and the opportunity of marriage came along. 'Better any marriage at all than none', a foolish old aunt used to say.

The woman of the well-to-do classes was made to understand early that the only door open to a life at once easy and respectable was that of marriage. Therefore she had to depend upon her good looks, according to the ideals of the men of her day, her charm, her little drawing-room arts.

(5) In October 1874, Elizabeth Wolstenholme, who was five months pregnant, married Ben Elmy at Kensington Register Office. Some members of the Married Women's Property Committee believed that Wolstenholme should resign as they felt the "scandal was harming the women's movement. Josephine Butler sent a letter to women leaders defending Elizabeth Wolstenholme and Ben Elmy.

They have sinned against no law of Purity. They went through a most solemn ceremony and vow before witnesses. I knew of this true marriage before God - early in 1874. It would have been a legal marriage in Scotland. They blundered; but their whole action was grave and pure. The English marriage laws are impure. English law… sins against the law of purity. It is a species of legal prostitution the woman being the man's property.

(6) In 1867 Lydia Becker made a speech at a meeting of the Manchester Suffrage Society on the subject of marriage.

I think that the notion that the husband ought to have the headship or authority over his wife, is the root of all social evils… Husband and wife should be co-equal. In a happy marriage there is no question of 'obedience'.

(7) In 1879 Emmeline Goulden married Dr. Richard Pankhurst in 1879.

I came to know Dr. Richard Pankhurst, a lawyer… who was a supporter of woman's suffrage… Dr. Pankhurst acted as counsel for the Manchester women who tried in 1868 to be placed on the register as voters. He also drafted the bill giving married women absolute control over their property and earnings, a bill, which became law in 1882.

About a year after my marriage my daughter Christabel was born, and in another eighteen months my second daughter Sylvia came. Two other children followed and for some years I was rather deeply immersed in my domestic affairs. I was never so absorbed with home and children, however, that I lost interest in community affairs. Dr. Pankhurst did not desire that I should turn myself into a household machine.

(8) Louisa Garrett Anderson, the daughter of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, wrote about attitudes towards marriage when her mother was a young woman in the 1860s.

To remain single was thought a disgrace and at thirty an unmarried woman was called an old maid. After their parents died, what could they do, where could they go? If they had a brother, as unwanted and permanent guests, they might live in his house. Some had to maintain themselves and then, indeed, difficulty arose. The only paid occupation open to them a gentlewoman was to become a governess under despised conditions and a miserable salary. None of the professions were open to women; there were no women in Government offices; no secretarial work was done by them. Even nursing was disorganized and disreputable until Florence Nightingale recreated it as a profession by founding the Nightingale School of Nursing in 1860.

(9) In 1883 Isabella Ford described her first visit to the Independent Labour Party in Colne Valley.

There was a tea party… The men poured out the tea, cut the bread and butter, and washed everything up, without any feminine help and without any accidents! A party, that included the education of men… as well as the education of women, that gave one such skill and dexterity, and the other wider and truer views of life, was the party for me I felt, so I joined.

(10) In 1890 Clementina Black wrote a pamphlet On Marriage where she explained why some women were unwilling to get married.

Marriage, like all other human institutions, is not permanent and alterable in form, but necessarily changes shape with the changes of social development. The forms of marriage are transitional, like the societies in which they exist. Each age keeps getting ahead of the law, yet there are always some laggards of whom the law for the time being is ahead. The main tendency of our own age is towards greater freedom and equality, and the law is slowly modifying to match…. At present the strict letter of the law denies to a married woman the freedom of action which more and more women are coming to regard not only as their just but also as their dearest treasure; and this naturally causes a certain unwillingness on the part of the thoughtful women to marry… That law and custom should alike enlarge so as to suit the growing ideal is evidently desirable… we can all of us influence custom a little, since custom, after all, is only made up of many individual examples… Easier divorce may be necessary, but the opportunity of making wiser and happier marriages is more necessary still.

(11) In December 1909, Elizabeth Robins wrote an article, Votes for Women, that criticised British marriage laws.

The children's mother has no legal right to a voice in deciding how they shall be nursed; how or where educated; what trade or profession they shall adopt; in what form of religion they shall be instructed.

If a father wants his child vaccinated, or if he is merely indifferent, and so does not lay an objection before the magistrate, the mother cannot prevent the child being vaccinated. If the father wishes the child to be left unvaccinated, the mother cannot legally have it done.

The late Sir Horace Davy introduced a Bill, which proposed that father and mother should be acknowledged equal guardians of their children. This just and logical reform secured only nineteen votes in the House of Commons.

(12) On 21st May 1897 Selina Cooper gave birth to a baby son. Named John Ruskin after Selina's favourite writer, the baby was sometimes taken out in his pram by his five-year-old cousin. Selina's daughter, Mary later recalled what happened when John Ruskin was four-months old.

My cousin took him down Clitheroe Road, where the station is… there was a thunderstorm and the baby got soaked… My cousin was only little and he couldn't pull the pram cover down. My mother was frantic… when the baby came home he was in a pool of water… John Ruskin caught severe bronchitis… he died from bronchitic convulsions… She never talked about her dead son… After she died I found an old book… It was full of pictures of babies she cut out of newspapers. Young babies… I never saw her cutting out these pictures… She must have been gradually cutting them out all the time. Oh, there must have been about twenty. And all babies, not young children.

(13) In 1891 Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence began work as a social worker in a working-class area of London. She wrote about her experiences in her book My Part in a Changing World.

Drunkenness was extremely common… It seemed for many the only refuge from depression and misery. The effect of drunkenness upon the ordinary relationship of husband and wife, parents and children, was disastrous. There was a woman whose husband used to knock her about badly when in drink. But he went to the Mission Hall in the district, was converted and signed the pledge. All went well for some time until she again turned up with several bruises. "Oh, Mrs. Smith, has your husband taken to drink again?" She replied: "Oh, no, that was another lady what done that! Since my husband went to the Misson Hall, he ain't like a husband at all - he is more like a friend!"

There was a particular point of view with regard to wife-beating. A friend of mine was once walking along the street and she passed a woman with a black eye. At the same time two other women passed, and one of them remarked: "Well, all I can say is, she is a lucky woman to have a husband to take that trouble with her." Another woman who had gone through a similar experience remarked: "Well, it ain't pleasant to be knocked about, but the making-up is lovely."

(14) In a speech she made at the Wardorf Hotel on 4th May 1909, Elizabeth Robins argued that women's equality would improve relationships between the sexes.

My own adhesion to the Suffrage Cause was given largely because I saw that only through political equality may we hope to see established a true understanding and a happier relationship between the sexes.

Changes in society… have long been tending towards increasing separation between men and women, in practically all the interests of life save one. In the world of industry, of business, of thought - even in what is called society, the growing tendency has been to divide the world into two separate camps. Men who are "doing things," or want to do things, have less and less time to give to an order of beings having no share and, as it came to seem, no stake in the varies aspects - save one - of the great game of life. The conditions of modern life are more and more separating the sexes. Instead of still further dividing us, Women's Suffrage is in reality the bridge between the chasm.

(15) Marie Stopes book Married Love was published in March 1918. The book created a sensation and sold 2,000 copes within a fortnight. Many men objected to the feminist sentiments expressed in the book.

Far too often, marriage puts an end to woman's intellectual life. Marriage can never reach its full stature until women possess as much intellectual freedom and freedom of opportunity within it as do their partners.

That at present the majority of women neither desire freedom for creative work, nor would know how to use it, is only a sign that we are still living in the shadow of the coercive and dwarfing influences of the past.

(16) In March 1911, Charles Buxton, the eldest son of Lord Buxton, a wealthy businessman and Postmaster General in Herbert Asquith's Cabinet, asked Octavia Wilberforce to marry him. Although under extreme pressure from her parents, Octavia refused. She explained her thoughts on receiving Charles Buxton's proposal, in a letter she wrote to her close friend, Elizabeth Robins.

When I was eighteen I would have married anything that might have asked me if I thought it would have been advantageous and conducive to fun. Didn't believe in any silly rot like love and I might have been the most amenable daughter alive.

When Charles Buxton's letter came I was most awfully sorry and wished I had never seen the boy. I was perfectly miserable and from trying to imagine how he felt I almost felt I was a criminal. When he came and I walked along the lane with him I felt I was a beast and quite dreadfully sorry. But when he spoke of it… I suddenly felt so revolted at what it all meant from my point of view.

Some people are cut out for marriage; they are made for it and would be most happy in it. Perhaps people are made differently, but I am not cut out for it. Everybody I know would be shocked and horrified at that statement and at this: the very thought of it makes me shudder and it revolts me.

(17) In her autobiography, I Have Been Young, Helena Swanwick, complained about her mother going through her private papers.

I was angry at what I held to be a violation of my privacy and I exclaimed 'You forget I'm a person!' I remember this because my mother thought it so funny, and for long after she mocked me saying 'I forgot! You're a Person!' A boy might be a person but not a girl. This was the ineradicable root of our differences. All my brothers had rights as persons; not I. Till I married (at the age of twenty four), she never, in her heart, conceded one personal right. Once I had a husband her whole attitude towards me changed and just as formerly I could do nothing right, so latterly, I could do nothing wrong in her eyes.

(18) Margaret Haig Thomas, This Was My World (1933)

During those early years I spent much time in walking and driving all over the country. Soon after I grew up I learned how to drive a car and acquired a second-hand one of my own, which my parents allowed me to drive about alone at all hours of the day. In those days, even that made for more freedom than many young women possessed. On the other hand, I was never allowed to stay the night away alone. I remember on one occasion when with an unmarried cousin, who must have been thirty at the time, I went for a few days' motoring tour which included stopping at one or two hotels, we were made to take a stable-boy with us to act as chaperone.