On this day on 5th February

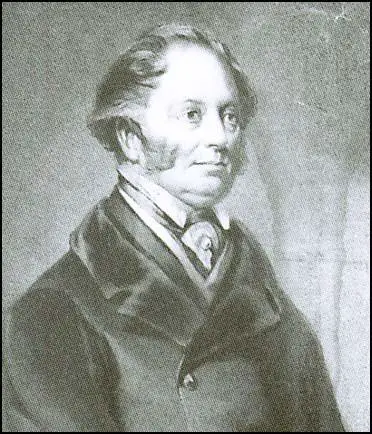

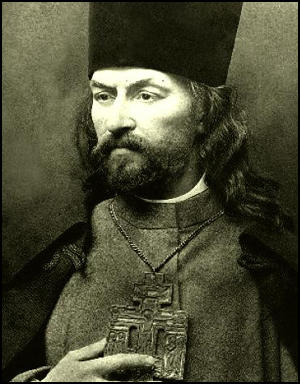

On this day in 1774 Edward Baines was born. Edward Baines, the son of Richard and Jane Baines, was born in Preston on 5th February, 1774. Richard Baines worked as an excise officer until he opened a small grocer's shop in the village of Walton-le-dale.

Edward was educated at Preston Grammar School until the age of sixteen when he went to work for Thomas Walker, a printer and stationer in Preston.

After hearing about Richard Arkwright and his successful business in Cromford, Baines became involved in the textile industry. In 1793 he purchased some carding and roving machines from Arkwright and started up business in the village of Brindle, seven miles from Preston.

In 1793 Walker began publishing the Preston Review. The political views expressed in the newspaper upset powerful Tories in the town and the following year it was forced to closed. Unable to work as a journalist in Preston, Baines decided to move to Leeds where he found work with Binns and Brown, the publishers of The Leeds Mercury. In 1797 Edward Baines asked his father to loan him £100. With this money he joined forces with his friend John Fenwick, to go into business as a general printer.

After obtaining a loan of £950 from some Whig friends Baines bought the The Leeds Mercury in 1801. Although the overall cost was £1 552, his down payment was £700 followed by £500 in 1802 and £352 in 1803.

Edward Baines was a staunch Nonconformistand supported the cause of the Dissenters. He advocated that industrial towns and cities such as Leeds should be represented in Parliament. His greatest journalistic scoop came in June 1817 when he revealed that the Government of Lord Liverpool was using agent provocateurs.

Edward Baines also strongly disapproved of the Slave Trade and willingly used The Leeds Mercury to support the campaign of Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp to bring an end to slavery in the British Empire. However, influenced by his many friends involved in the textile industry, Edward Baines was totally opposed to factory legislation.

Although in favour of some aspects of parliamentary reform, Edward Baines disagreed with the working class being given the vote. Baines' criticisms of those advocating universal suffrage resulted him becoming very unpopular with radicals in Leeds.

On 9th August 1819, Baines sent his 19 year old son, also named Edward Baines, to cover the parliamentary reform meeting in Manchester that was to be addressed by Henry Hunt. According to the author of The Life of Edward Baines (2009: "He felt it would offer his son a valuable experience and an ideal opportunity to hone his journalistic skills." The meeting turned into the Peterloo Massacre and his report inThe Leeds Mercury blamed both the organisers of the event and the officers of the yeomanry for the disaster.

In January 1827, Edward Baines announced that the The Leeds Mercury was now owned by "Baines and Son". When he acquired the Liverpool Advertiser (renamed the Liverpool Times) in 1829 he arranged for his son to run the newspaper.

After the 1832 Reform Act Leeds was granted two members of parliament. In the next General Election Edward Baines and The Leeds Mercury supported the two Whig candidates, John Marshall, the owner of the largest flax-spinning factory in Leeds, and the historian Thomas Macaulay. Marshall (2,012) and Macaulay (1,914) were elected. Michael Sadler, the leader of the factory reform movement received only 1,590 votes and was defeated.

In 1833 Thomas Macaulay resigned his seat in order to take up a post in India. Edward Baines was chosen as the Liberal candidate to replace Macaulay. In February 1834 Edward Baines (1,951) defeated the Tory candidate, Sir John Beckett (1,917). His son now took on full responsibility for running The Leeds Mercury. Baines senior later recalled that he was grateful for his son's "indefatigable exertions in the management of the Leeds Mercury newspaper and my affairs and interests generally during the time that I sat in Parliament."

In the House of Commons Baines supported the cause of the Dissenters. This included the measure to abolish Church Rates and bill to register Dissenters' Marriages. Baines also played an important role in the opposition to factory legislation, universal suffrage and government control over education.

Edward Baines's son, Edward Baines was also an opponent of factory legislation. In 1835 Edward Baines wrote History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain. In the book Baines attacked those who had campaigned against child labour. He accused them of providing a false picture of what it was like to work in a textile factory. Baines claimed in his book that "factory labour is far less injurious than many other forms of employment". He went on to argue that many of the factory children were born in bad health and that they "sink under factory labour, as they would under any kind of labour."

Baines was admitted to Salem Congregational Church on 3rd January 1840. Declining health forced Baines to retire from the House of Commons in May 1841. His suggestion that his friend, Joseph Hume, should replace him was accepted. However in the election that followed, Hume was defeated by William Becket, the Tory candidate.

Edward Baines was totally opposed to the idea of state education and campaigned against the government bill to set up factory schools. At a meeting in Leeds in 1843 he argued: "There is one thing this measure will do for the poor. It will deteriorate their condition. It will deprive them of their independence and lead them to look up for state supplies when they ought to look to their own industry. It will make them look upon the state instead of themselves."

Edward Baines died on 3rd August 1848.

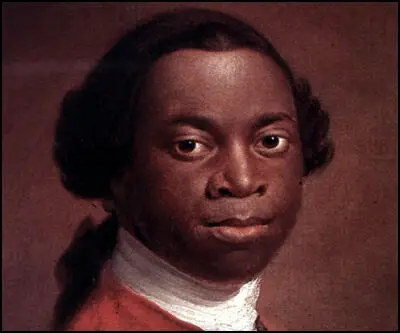

On this day in 1788 Olaudah Equiano publishes a letter attacking slavery. "To kidnap our fellow creatures, however they may differ in complexion, to degrade them into beasts of burthen, to deny them every right but those, and scarcely those we allow to a horse, to keep them in perpetual servitude, is a crime as unjustifiable as cruel; but to avow and to defend this infamous traffic required the ability and the modesty of you and Mr. Tobin. Can any man be a Christian who asserts that one part of the human race were ordained to be in perpetual bondage to another."

Olaudah Equiano was born in Essaka, an Igbo village in the kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria) in 1745. His father was one of the province's elders who decided disputes. According to James Walvin "Equiano described his father as a local Igbo eminence and slave owner".

When he was about eleven, Equiano was kidnapped and after six months of captivity he was brought to the coast where he encountered white men for the first time. Equiano later recalled in his autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1787): "The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions, too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, (which was very different from any I had ever heard) united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country."

Olaudah Equiano was placed on a slave-ship bound for Barbados. "I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable."

After a two-week stay in the West Indies Equiano was sent to the English colony of Virginia. In 1754 he was purchased by Captain Henry Pascal, a British naval officer. He was given the new name of Gustavus Vassa and was brought back to England. According to his biographer, James Walvin: "For seven years he served on British ships as Pascal's slave, participating in or witnessing several battles of the Seven Years' War. Fellow sailors taught him to read and write and to understand mathematics. He was also converted to Christianity, reading the Bible regularly on board ship. Baptized at St Margaret's Church, Westminster, on 9 February 1759, he struggled with his faith until finally opting for Methodism."

By the end of the Seven Years' War he reached the rank of able seaman. Although he was freed by Pascal he was re-enslaved in London in 1762 and shipped to the West Indies. For four years he worked for a Montserrat based merchant, sailing between the islands and North America. "I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new Negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them." James Walvin points out that "Equiano... also trading to his own advantage as he did so. Ever alert to commercial openings, Equiano accumulated cash and in 1766 bought his own freedom."

Equiano now worked closely with Granvile Sharpe and Thomas Clarkson in the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Equiano spoke at a large number of public meetings where he described the cruelty of the slave trade. In 1787 Equiano helped his friend, Offobah Cugoano, to published an account of his experiences, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of America. Copies of his book was sent to George III and leading politicians. He failed to persuade the king to change his opinions and like other members of the royal family remained against abolition of the slave trade.

Equiano published his own autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African in 1789. He travelled throughout England promoting the book. It became a bestseller and was also published in Germany (1790), America (1791) and Holland (1791). He also spent over eight months in Ireland where he made several speeches on the evils of the slave trade. While he was there he sold over 1,900 copies of his book.

David Dabydeen has argued: "With Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, Equiano was a major abolitionist, working ceaselessly to expose the nature of the shameful trade. He travelled throughout Britain with copies of his book, and thousands upon thousands attended his readings. When John Wesley lay dying, it was Equiano's book he took up to reread."

On 7th April 1792 Equiano married Susanna Cullen (1761-1796) of Soham, Cambridgeshire. The couple had two children, Anna Maria (16th October 1793) and Johanna (11th April 1795). However, Anna Maria died when she was only four years old. Equiano's wife died soon afterwards. During this period he was a close friend of Thomas Hardy, secretary of the London Corresponding Society. Equiano became an active member of this group that campaigned in favour of universal suffrage.

Olaudah Equiano was appointed to the expedition to settle former black slaves in Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa. However, he died at his home at Paddington Street, Marylebone, on 31st March, 1797 before he could complete the task.

The historian, James Walvin, has argued: "After his death his book was anthologized by abolitionists (especially before the American Civil War). Thereafter, however, Equiano was virtually forgotten for a century. In the 1960s his autobiography was rediscovered and reissued by Africanist scholars; various editions of his Narrative have since sold in large numbers in Britain, North America, and Africa. Equiano's autobiography remains a classic text of an African's experiences in the era of Atlantic slavery. It is a book which operates on a number of levels: it is the diary of a soul, the story of an autodidact, and a personal attack on slavery and the slave trade. It is also the foundation-stone of the subsequent genre of black writing; a personal testimony which, however mediated by his transformation into an educated Christian, remains the classic statement of African remembrance in the years of Atlantic slavery." Chinua Achebe has called him "the father of African literature" whereas Henry Louis Gates claimed him for America as "the founding father of the Afro-American literary tradition".

In 2005 Vincent Carretta published his book, Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man. He argued that he had found a document that suggests that Equiano was really born in South Carolina. As David Dabydeen points out: "In other words, Equiano may never have set foot in Africa, never mind boarded a slave ship, and the narrative of his early life may be pure fiction." However, he adds: "Equiano's autobiography, Carretta suggests, is a monumental 18th-century text, a unique mixture of travel-writing, sea lore, sermon, economic tract and fiction. That the early chapters may have invented a life in Africa only adds to our appreciation of Equiano's imaginative depth and literary talent."

On this day in 1788 Robert Peel was born in Bury, Lancashire. His father, Sir Robert Peel (1750-1830), was a wealthy cotton manufacturer and member of parliament for Tamworth. Robert was trained as a child to become a future politician. Every Sunday evening he had to repeat the two church sermons that he had heard that day.

Robert Peel was educated at Harrow School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he won a double first in classics and mathematics. In 1809 Sir Robert Peel rewarded his son academic success by buying him the parliamentary seat of Cashel in County Tipperary (exchanged for Chippenham in 1812).

Robert Peel entered the House of Commons in April 1809, at the age of twenty-one. Like his father, Robert Peel supported the Duke of Portland's Tory government. He made an immediate impact and Charles Abbott, the Speaker of the Commons, described Peel's first contribution to a debate as the "the best first speech since that of William Pitt."

After only a year in the House of Commons the Duke of Portland offered him the post of under-secretary of war and the colonies. Working under Lord Liverpool, Peel helped to direct the military operations against the French.

When Lord Liverpool became prime minister in May 1812, Peel was appointed as chief secretary for Ireland. In his new post Peel attempted to bring an end to corruption in Irish government. He tried to stop the practice of selling public offices and the dismissal of civil servants for their political views. At first Peel also attempted to end those aspects of government that gave preference to Protestants over Catholics. However, Robert Peel was not successful in carrying out this policy and eventually he became seen as one of the leading opponents to Catholic Emancipation.

In 1814 he decided to suppress the Catholic Board, an organisation started by Daniel O'Connell. This was the start of a long conflict between the two men. In 1815 Peel challenged O'Connell to a duel. Peel travelled to Ostend but O'Connell was arrested on the way to fight the duel.

In 1817 Robert Peel decided to retire from his post in Ireland. This upset the Irish Protestants in the House of Commons and fifty-seven of them signed a petition urging him not to leave a post that they believed he had "administered with masterly ability". Oxford University acknowledged Peel's "services to Protestantism" by inviting him to become its member of the House of Commons.

In 1822 Robert Peel rejoined Lord Liverpool's government when he accepted the post of Home Secretary. Over the next five years Peel was responsible for large-scale reform in the legal system. This involved repealing over 250 old statutes.

Lord Liverpool was struck down by paralysis in February 1827 and was replaced by George Canning as prime minister. Canning was an advocate of Catholic Emancipation and as Peel was strongly opposed to this, he felt he could not serve under the new prime minister and resigned from office. After the death of Canning he returned to government as Home Secretary in the government led by the Duke of Wellington.

On 26th July, 1828, Lord Anglesey, wrote to Peel arguing that Ireland was on the verge of rebellion and asked him to use his influence to gain concessions for the Catholics. Although Peel had opposed Catholic Emancipation for twenty years, Lord Anglesey's letter encouraged him to reconsider his position. Peel now wrote to Wellington saying that "though emancipation was a great danger, civil strife was a greater danger". He also added that as William Pitt had rightly said: "to maintain a consistent attitude amid changed circumstances is to be a slave of the most idle vanity".

Although the Duke of Wellington agreed with Peel, King George III was violently opposed to Catholic Emancipation. When Wellington's government threatened to resign the king reluctantly agreed to a change in the law. When Peel introduced the Catholic Emancipation Act on 5th March, 1829, he told the House of Commons that the credit for the measure belonged to his long-time opponents, Charles Fox and George Canning.

For a long time politicians had been concerned about the problems of law and order in London. In 1829 Robert Peel decided to reorganize the way London was policed. As a result of this reform, the new metropolitan police force became known as "Peelers" or "Bobbies".

In November 1830, Wellington's government was replaced by a new administration headed by Earl Grey. For the first time in over twenty years in the House of Commons, Peel was now a member of the opposition. Peel was totally against Grey's proposals for parliamentary reform. Between 12th and 27th July 1831, Peel made forty-eight speeches in the Commons against this measure. One of Peel's main arguments was that the system of rotten boroughs had enabled distinguished men to enter parliament.

After the passing of the 1832 Reform Act the Tories were heavily defeated in the general election that followed. Although victorious at Tamworth, Peel, now leader of the Tories, only had just over hundred MPs he could rely on to support him against Earl Grey's government.

In November 1834 King William IV dismissed the Whig government and appointed Robert Peel as his new prime minister. Peel immediately called a general election and during the campaign issued what became known as the Tamworth Manifesto. In his election address to his constituents in Tamworth, Peel pledged his acceptance of the 1832 Reform Act and argued for a policy of moderate reforms while preserving Britain's important traditions. The Tamworth Manifesto marked the shift from the old, repressive Toryism to a new, more enlightened Conservatism.

The general election gave Peel more supporters although there were still more Whigs than Tories in the House of Commons. Despite this, the king invited Peel to form a new administration. With the support of the Whigs, Peel's government was able to pass the Dissenters' Marriage Bill and the English Tithe Bill. However, Peel was constantly being outvoted in the House of Commons and on 8th April 1835 he resigned from office.

In August 1841 Robert Peel was once again invited to form a Conservative administration. Over the last few years Britain had been spending more than it was earning. Peel decided the government had to increase revenue. On 11th March, 1842, he announced the introduction of income-tax at sevenpence in the pound. He added, that he hoped that this was enable the government to reduce duties on imported goods.

In 1843 Peel once more had problems with Daniel O'Connell, who was leading the campaign against the Act of Union. O'Connell announced a large meeting to be held at Clontarf. The British government pronounced it illegal and when O'Connell continued to go ahead with his planned Clontarf meeting he was arrested and imprisoned for conspiracy. Peel attempted to overcome the religious conflict in Ireland by setting up the Devon Commission to inquire into the "state of the law and practice in respect to the occupation of land in Ireland." He also increased the grant to Maynooth College for the education of the Irish priesthood, from £9,000 to £26,000 a year.

However, Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland was severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn. Although the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, the policy split the Conservative Party and Peel was forced to resign.

Robert Peel continued to attend the House of Commons and gave considerable support to Lord John Russell and his administration in 1846-47. On 28th June 1850 he gave an important speech on Greece and the foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. The following day, while riding up Constitution Hill, he was thrown from his horse. Peel was badly hurt and on 2nd July, 1850, he died from his injuries.

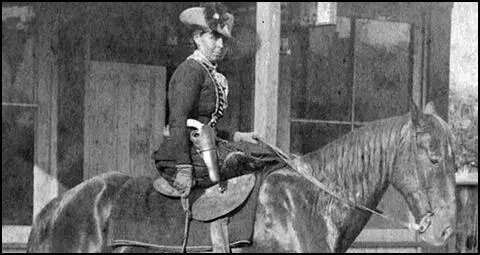

On this day in 1846 Belle Starr was born in Carthage, Missouri. Myra Belle Shirley was born in Carthage, Missouri, on 5th February, 1846. During the American Civil War she worked as a courier for Confederate guerillas.

In 1866 Belle had a relationship with Cole Younger. She gave birth to a daughter, Pearl, but it is unclear who was the father of the child. She later married James Reed in Texas, but in 1870, her husband became a fugitive when he killed a man in a fight. Reed became an outlaw and took part in a $30,000 robbery in November, 1973. Two years later Reed was killed by a bounty hunter.

Belle now became an outlaw and along with a gang that included Jack Spaniard, Jim French and Blue Duck, was involved in stealing horses. In 1880 Belle married Sam Starr, a Cherokee.

In 1882 Belle Starr came before Isaac Parker, the Hanging Judge at Fort Smith. Charged with being the leader of a band of horse-thieves. Found guilty she was sent to prison for only six months.

On 3rd February 1889 Belle Starr was murdered by an unknown assassin in Oklahoma.

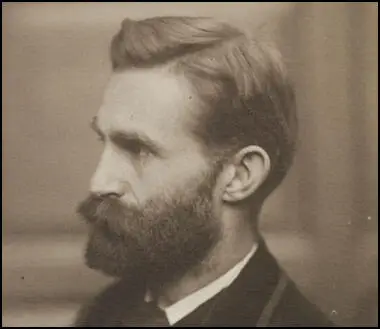

Frank Podmore was born at Elstree, Hertfordshire, on 5th February 1856. The son of Rev. Thompson Podmore, the Headmaster of Eastbourne College, Frank was educated at Haileybury School and Pembroke College. He graduated from Oxford University with a first in natural science in 1877.

As an undergraduate Podmore developed an interest in spiritualism and carried out research into psychic phenomena. He joined the Society for Physical Research and although he eventually rejected spiritualism, he did support the idea of extra-sensory perception.

In 1881 Podmore met Edward Pease, a young stockbroker. They discovered a mutual interest in socialism, and joined the Progressive Association, founded in November 1882. They took a keen interest in the utopian philosophy of Thomas Davidson, and with a few others formed a society, the Fellowship of the New Life. Other members included Edward Carpenter, Edith Lees, Edith Nesbit, Isabella Ford, Henry Hyde Champion, Hubert Bland and Henry Stephens Salt. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In October 1883 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland decided to form a socialist debating group with their Quaker friend Edward Pease. They were also joined by Frank Podmore and Havelock Ellis and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles. Podmore's home, 14 Dean's Yard, Westminster, became the official headquarters of the organisation.

Hubert Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. By March 1884 the group had twenty members. In April 1884 Edith Nesbit wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

George Bernard Shaw joined the Fabian Society in August 1884. Nesbit wrote: "The Fabian Society is getting rather large now and includes some very nice people, of whom Mr. Stapelton is the nicest and a certain George Bernard Shaw the most interesting. G.B.S. has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

Over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Edith Lees, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Charles Trevelyan, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Edward Carpenter, Clement Attlee, Ramsay MacDonald, Emmeline Pankhurst,Walter Crane, Arnold Bennett, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Hugh Dalton, C. E. M. Joad, Rupert Brooke, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

Early talks at the Fabian Society included: How Can We Nationalise Accumulated Wealth by Annie Besant, Private Property by Edward Carpenter, The Economics of a Postivist Community by Sidney Webb and Personal Duty under the Present System by Graham Wallas.

In 1886 Podmore and Sidney Webb carried out an investigation into unemployment. In the Fabian Society pamphlet, The Government Organisation of Unemployed Labour they advocated the funding of rural land armies but declined to endorse large-scale public employment as they feared it would encourage inefficiency.

On 11th June 1891 Podmore married Eleonore Oliver Bramwell. As well as holding a senior position in the Post Office he published a series of books. This included Apparitions and Thought-Transference (1894), Studies in Psychical Research (1897) and Modern Spiritualism: a History and a Criticism (1902). His major work was a detailed study of the life and ideas of Robert Owen. The two volume Robert Owen was published in 1906. In this work Podmore argued that Owen was the founding father of both socialism and spiritualism.

According to his biographer, Alan Gauld: "In 1907 Podmore was compelled to resign without pension from the Post Office because of alleged homosexual involvements. He separated from his wife, and went to live with his brother Claude, rector of Broughton, near Kettering."

Frank Podmore died by drowning at a swimming pool in Malvern on the night of 14th August 1910. Despite evidence that he had committed suicide, a verdict of "found drowned" was returned. He was buried in Malvern Wells Cemetery.

On this day in 1870 Georgi Gapon was born. Georgi Gapon, the son of a peasant, was born in the village of Beliki, near Poltava in Russia on 17th February (O.S. 5th February) 1870. His father was a Cossack and his mother came from peasant stock.

Gapon later stressed that he came from a plebeian background. His biographer, Walter Sablinsky, claims that sources differ on this point: "One of his former teachers described the family as prosperous, and Soviet historians characterize his background as that of a wealthy peasant or kulak."

At school one of his teachers, Ivan Mikhailovich Tregubov, introduced him to the ideas of Leo Tolstoy. He described him as "a serious boy, intelligent and pensive, although a lively one. He was always one of his top students, noted for his diligence and high degree of curiously." According to Lionel Kochan, Tregubov had a long-term impact on Gapon.

Gapon entered the Theological Academy of St Petersburg and "combined his studies with missionary work amongst the poor and Chaplaincy duties at a St Petersburg deportation centre for convicts." Gapon became a religious teacher at the St. Olga children's orphanage. However, he eventually lost his faith in God and developed a strong desire to become a doctor as he thought in that role he would be more use to the poor. After failing to take his final exam the Theological Academy commented that he had "no particular desire to pursue a religious calling".

In 1893 Gapon took a job as a zemstvo statistician, supplementing his income with money earned working as a private tutor. During this period he met the daughter of a local merchant in a house in which he was giving private lessons. The family objected to a proposed marriage due to Gapon's economic circumstances and he therefore made an appeal to Bishop Ilarion of Poltava, about his situation. The bishop interceded with the family and was granted permission to marry and re-entered the priesthood.

Gapon married in 1896 and he was assigned to a lucrative post in a church in Poltava. His services were well attended and his fast growing reputation for genuine concern for the poor drew people away from other churches. During these years Gapon enjoyed a happily married life, with his wife giving birth to two children. Unfortunately she died after a brief illness in 1898.

In 1902 Gapon became a priest in St. Petersburg where he showed considerable concern for the welfare of the poor. He soon developed a large following, "a handsome, bearded man, with a rich baritone voice, had oratorical gifts to a spell-binding degree". The workers in St Petersburg had plenty to complain about. It was a time of great suffering for those on low incomes. About 40 per cent of houses had no running water or sewage. The Russian industrial employee worked on average an 11 hour day (10 hours on Saturday). Conditions in the factories were extremely harsh and little concern was shown for the workers' health and safety. Attempts by workers to form trade unions were resisted by the factory owners. In 1902 the army was called out 365 times to deal with unrest among workers.

Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior, rejected all calls for reform. Lionel Kochan pointed out that "Plehve was the very embodiment of the government's policy of repression, contempt for public opinion, anti-semitism and bureaucratic tyranny" and it was no great surprise when Evno Azef, head of the Terrorist Brigade of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, ordered his assassination.

On 28th July, 1904, Plehve was killed by a bomb thrown by Egor Sazonov on 28th July, 1904. Emile J. Dillon, who was working for the Daily Telegraph, witnessed the assassination: "Two men on bicycles glided past, followed by a closed carriage, which I recognized as that of the all-powerful minister (Vyacheslav Plehve). Suddenly the ground before me quivered, a tremendous sound as of thunder deafened me, the windows of the houses on both sides of the broad streets rattled, and the glass of the panes was hurled on to the stone pavements. A dead horse, a pool of blood, fragments of a carriage, and a hole in the ground were parts of my rapid impressions. My driver was on his knees devoutly praying and saying that the end of the world had come.... Plehve's end was received with semi-public rejoicings. I met nobody who regretted his assassination or condemned the authors."

Plehve was replaced by Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky, as Minister of the Interior. He held liberal views and hoped to use his power to create a more democratic system of government. Sviatopolk-Mirsky believed that Russia should grant the same rights enjoyed in more advanced countries in Europe. He recommended that the government strive to create a "stable and conservative element" among the workers by improving factory conditions and encouraging workers to buy their own homes. "It is common knowledge that nothing reinforces social order, providing it with stability, strength, and ability to withstand alien influences, better than small private owners, whose interests would suffer adversely from all disruptions of normal working conditions."

In February, 1904, Sviatopolk-Mirsky's agents approached Father Gapon and encouraged him to use his popular following to "direct their grievances into the path of economic reform and away from political discontent". Gapon agreed and on 11th April 1904 he formed the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg. Its aims were to affirm "national consciousness" amongst the workers, develop "sensible views" regarding their rights and foster amongst the members of the union "activity facilitating the legal improvements of the workers' conditions of work and living".

By the end of 1904 the Assembly had cells in most of the larger factories, including a particularly strong contingent at the Putilov works. The overall membership has been variously estimated between 2,000 and 8,000. Whatever the true figure, the strength of the Assembly and of its sympathizers exceeded by far that of the political parties. For example, in St Petersburg at this time, the local Menshevik and Bolshevik groups could muster no more than 300 members each.

Adam B. Ulam, the author of The Bolsheviks (1998) was highly critical of the leader of the Assembly of Russian Revolution: "Gapon had certain peasant cunning, but was politically illiterate, and his personal tastes were rather inappropriate for either a revolutionary or a priest: he was unusually fond of gambling and drinking. Yet he became an object of a spirited competition among various branches of the radical movement." Another revolutionary figure, Victor Serge, saw him in a much more positive light. "Gapon is a remarkable character. He seems to have believed sincerely in the possibility of reconciling the true interests of the workers with the authorities' good intentions".

According to Cathy Porter: "Despite its opposition to equal pay for women, the Union attracted some three hundred women members, who had to fight a great deal of prejudice from the men to join." Vera Karelina was an early member and led its women's section: "I remember what I had to put up with when there was the question of women joining... There wasn't a single mention of the woman worker, as if she was non-existent, like some sort of appendage, despite the fact that the workers in several factories were exclusively women." Karelina was also a Bolshevik but complained "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation.''

Adam B. Ulam claimed that the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg was firmly under the control of the Minister of the Interior: "Father Gapon... had, with the encouragement and subsidies of the police, organized a workers' union, thus continuing the work of Zubatov. The union had scrupulously excluded Socialists and Jews. For a while the police could congratulate themselves on their enterprise." David Shub, a Menshevik, agreed, claiming that the organization had been set up to "wean the workers away from radicalism".

Alexandra Kollontai, an important Bolshevik leader, did join the union with little difficulty. She was also a feminist and felt the Bolsheviks had not done enough to support the demands of women members. Kollontai believed that any organization that allowed factory women was preferable to the Bolsheviks' almost total silence about them, and "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation."

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike.

Father Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police".

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association."

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken."

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights."

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people.

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear."

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass."

The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded.

Georgi Gapon w later described what happened in his book The Story of My Life (1905): "The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them. Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air."

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." (30) It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded.

Father Gapon escaped uninjured from the scene and sought refuge at the home of Maxim Gorky: "Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path."

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad."

The massacre of an unarmed crowd undermined the standing of the autocracy in Russia. The United States consul in Odessa reported: "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the Tsar. The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present tsar will never again be safe in the midst of his people."

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances.

Lenin, who had been highly suspicious of Father Gapon, admitted that the formation of Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg and the occurrence of Bloody Sunday, had made an important contribution to the development of a radical political consciousness: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence."

Henry Nevinson, of The Daily Chronicle commented that Gapon was "the man who struck the first blow at the heart of tyranny and made the old monster sprawl." When he heard the news of Bloody Sunday Leon Trotsky decided to return to Russia. He realised that Father Gapon had shown the way forward: "Now no one can deny that the general strike is the most important means of fighting. The twenty-second of January was the first political strike, even if he was disguised under a priest's cloak. One need only add that revolution in Russia may place a democratic workers' government in power."

Trotsky believed that Bloody Sunday made the revolution much more likely. One revolutionary noted that the killing of peaceful protestors had changed the political views of many peasants: "Now tens of thousands of revolutionary pamphlets were swallowed up without remainder; nine-tenths were not only read but read until they fell apart. The newspaper which was recently considered by the broad popular masses, and particularly by the peasantry, as a landlord's affair, and when it came accidentally into their hands was used in the best of cases to roll cigarettes in, was now carefully, even lovingly, straightened and smoothed out, and given to the literate."

After the massacre Gapon left Russia and went to live in Geneva. Bloody Sunday made Father Gapon a national figure overnight and he enjoyed greater popularity "than any Russian revolutionary had previously commanded". One of the first people he met was George Plekhanov, the leader of the Mensheviks.

Plekhanov introduced Gapon to Pavel Axelrod, Vera Zasulich, Lev Deich and Fedor Dan. Gapon told them that he fully shared the views of this revolutionary group and this information was published in the Menshevik's newspaper, Vorwärts. Deich later recalled that they made efforts to give him an education in Marxism. They explained that the course of history was determined by objective historical laws, not by individual actions. Gapon also went to live with Axelrod.

Victor Adler sent Leon Trotsky a telegram after receiving a message from Pavel Axelrod. "I have just received a telegram from Axelrod saying that Gapon has arrived abroad and announced himself as a revolutionary. It's a pity. If he had disappeared altogether there would have remained a beautiful legend, whereas as an emigre he will be a comical figure. You know, such men are better as historical martyrs than as comrades in a party."

The leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRP) became upset by this development and used his friend, Pinchas Rutenberg, to try and get him to change his mind. Rutenberg received instructions "to make every effort to win him over". This included persuading him to live with SRP supporter, Leonid E. Shishko. "By inclination and temperament, Gapon was more at home with the Socialist Revolutionaries, who emphasized the force of individual action and revolutionary voluntarism."

Father Georgi Gapon saw himself as the leader of the coming revolution and believed that his first task was to unify the revolutionary parties. However, he preferred the SRP approach to politics. He told Lev Deich: "Theories are not important to them, only that the person possesses courage and be devoted to the people's cause. They do not demand anything from me, do not criticize my actions. On the contrary, they always praise me."

Victor Chernov was not convinced that Gapon really supported the SRP: "A party man, no matter what party, Gapon never was, nor was he capable of being one... Even if Gapon genuinely intended to follow a certain line of behavior, he could not do so. He would violate this promise, as he violated every promise he made to himself. At the first opportunity he would find it more tactically advantageous to act in a different manner. If you want, he was a complete and absolute anarchist, incapable of being a regular party member. Every organization he could conceive was only a superstructure of his unlimited authority. He alone had to be in the center of everything, know everything, hold in his hands the strings of the organization and manipulate the people tied to them in whatever manner he saw fit."

Father Gapon also had meetings with the anarchist, Peter Kropotkin. He also had conversations with Lenin and other Bolsheviks in Geneva. Nadezhda Krupskaya reported: "In Geneva Gapon began to visit us frequently. He talked a lot. Vladimir Il'ich listened attentively, trying to discern in his accounts the features of the approaching revolution". Lenin's conversations with Gapon helped persuade him to alter the Bolshevik agrarian policy.

Gapon's common law wife joined him in exile and in May, 1905, they visited London. He was offered a considerable sum from a publisher to write his autobiography, The Story of My Life (1905). While in the England he was asked to write an appeal against anti-Semitism. He readily agreed and wrote a pamphlet against Jewish pogroms, and refused to accept a share of the royalties offered him.

On 27th June, 1905, sailors on the Potemkin battleship, protested against the serving of rotten meat infested with maggots. The captain ordered that the ringleaders to be shot. The firing-squad refused to carry out the order and joined with the rest of the crew in throwing the officers overboard. The mutineers killed seven of the Potemkin's eighteen officers, including Captain Evgeny Golikov. They organized a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko, to run the battleship.

A delegation of the mutinous sailors arrived in Geneva with a message addressed directly to Father Gapon. He took the cause of the sailors to heart and spent all his time collecting money and purchasing supplies for them. He and their leader, Afanasi Matushenko, became inseparable. "Both were of peasant origin and products of the mass upheaval of 1905 - both were out of place among the party intelligentsia of Geneva."

The Potemkin Mutiny spread to other units in the army and navy. Industrial workers all over Russia withdrew their labour and in October, 1905, the railwaymen went on strike which paralyzed the whole Russian railway network. This developed into a general strike. Leon Trotsky later recalled: "After 10th October 1905, the strike, now with political slogans, spread from Moscow throughout the country. No such general strike had ever been seen anywhere before. In many towns there were clashes with the troops."

Tsar Nicholas II became increasingly concerned about the situation and entered into talks with Sergi Witte, his Chief Minister. As he pointed out: "Through all these horrible days, I constantly met Witte. We very often met in the early morning to part only in the evening when night fell. There were only two ways open; to find an energetic soldier and crush the rebellion by sheer force. That would mean rivers of blood, and in the end we would be where had started. The other way out would be to give to the people their civil rights, freedom of speech and press, also to have laws conformed by a State Duma - that of course would be a constitution. Witte defends this very energetically."

Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov, the second cousin of the Tsar, was an important figure in the military. He was highly critical of the way the Tsar dealt with these incidents and favoured the kind of reforms favoured by Sergi Witte: "The government (if there is one) continues to remain in complete inactivity... a stupid spectator to the tide which little by little is engulfing the country."

On 22nd October, 1905, Sergi Witte sent a message to the Tsar: "The present movement for freedom is not of new birth. Its roots are imbedded in centuries of Russian history. Freedom must become the slogan of the government. No other possibility for the salvation of the state exists. The march of historical progress cannot be halted. The idea of civil liberty will triumph if not through reform then by the path of revolution. The government must be ready to proceed along constitutional lines. The government must sincerely and openly strive for the well-being of the state and not endeavour to protect this or that type of government. There is no alternative. The government must either place itself at the head of the movement which has gripped the country or it must relinquish it to the elementary forces to tear it to pieces."

Later that month, Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. On 26th October the first meeting of the Soviet took place in the Technological Institute. It was attended by only forty delegates as most factories in the city had time to elect the representatives. It published a statement that claimed: "In the next few days decisive events will take place in Russia, which will determine for many years the fate of the working class in Russia. We must be fully prepared to cope with these events united through our common Soviet."

Over the next few weeks over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia and these events became known as the 1905 Revolution. Witte continued to advise the Tsar to make concessions. The Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov agreed and urged the Tsar to bring in reforms. The Tsar refused and instead ordered him to assume the role of a military dictator. The Grand Duke drew his pistol and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if the Tsar did not endorse Witte's plan.

On 30th October, the Tsar reluctantly agreed to publish details of the proposed reforms that became known as the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally it announced that no law would become operative without the approval of the State Duma. It has been pointed out that "Witte sold the new policy with all the forcefulness at his command". He also appealed to the owners of the newspapers in Russia to "help me to calm opinions".

These proposals were rejected by the St. Petersburg Soviet: "We are given a constitution, but absolutism remains... The struggling revolutionary proletariat cannot lay down its weapons until the political rights of the Russian people are established on a firm foundation, until a democratic republic is established, the best road for the further progress to Socialism."

On hearing about the publication of the October Manifesto, Gapon returned to Russia and attempted to gain permission to reopen the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg. However, Sergi Witte refused to meet him. Instead he sent him a message threatening to arrest him if he did not leave the country. He was willing to offer a deal that involved Gapon to come out openly in support of Witte and condemn all further insurrectionary activity against the regime. In return, he was given a promise that after the crisis was over, Gapon would be allowed back into Russia and he could continue with his trade union activities.

The Tsar decided to take action against the revolutionaries. Trotsky later explained that: "On the evening of 3rd December the St Petersburg Soviet was surrounded by troops. All the exists and entrances were closed." Leon Trotsky and the other leaders of the Soviet were arrested. Trotsky was exiled to Siberia and deprived of all civil rights. Trotsky explained that he had learnt an important political lesson, "the strike of the workers had for the first time brought Tsarism to its knees."

Georgi Gapon kept his side of the bargain. Whenever possible he gave press interviews praising Sergi Witte and calling for moderation. Gapon's biographer, Walter Sablinsky, has pointed out: "This, of course, earned him vehement denunciations from the revolutionaries... Suddenly the revolutionary hero had become an ardent defender of the tsarist government." Anger increased when it became clear that Witte was determined to pacify the country by force and all the revolutionary leaders were arrested.

Gapon's reputation took another blow when it was reported by the New York Tribune on 24th December 1905 that he had been seen in a casino in Monte Carlo. The following day the newspaper printed a photograph of the workers on the barricades in Moscow with a photograph of Gapon at the casino with Grand Duke Cyril Vladimirovich under the caption: "Grand Duke Cyril faces Father Gapon in Monte Carlo at the same roulette table". Gapon justified his decision by saying that to be on the Riviera and not visit a casino was like being in Rome and not seeing the Pope.

Victor Chernov, Evno Azef, and Pinchas Rutenberg held a meeting to discuss the fate of Gapon. Azef, the head of the organization, that carried out political assassinations for the Socialist Revolutionary Party, argued that Gapon should be "done away with like a viper". Chernov rejected this idea and pointed out that he was still revered by ordinary workers, and that if he was murdered the SRP would be accused of killing him over political differences.

Azef disagreed with this view and gave orders to Rutenberg to kill Gapon. On 26th March 1906, Georgi Gapon arrived to meet Rutenberg in a rented cottage in Ozerki, a little town north of St. Petersburg. Rutenberg and three other members of the SRP murdered Gapon. "Gapon's hands were tied, and he was hanged from a coat hook on the wall. Since the hook was not high enough, the executioners sat on his shoulders, pushing him down until he was strangled." The cottage was locked, and it was over a month before the body was discovered.

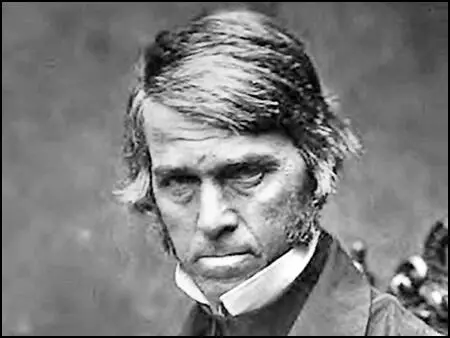

On this day in 1881 Thomas Carlyle died. Thomas Carlyle, the eldest son of James Carlyle (1757–1832), a stonemason, and Margaret Aitken (1771–1853), the daughter of a bankrupt Dumfriesshire farmer, was born in Ecclefechan in Scotland, on 4th December, 1795. His mother gave birth to eight children after Thomas: Alexander (1797–1876), Janet (1799–1801), John Aitken Carlyle (1801–1879), Margaret (1803–1830), James (1805–1890), Mary (1808–1888), Jane (1810–1888), and a second Janet (1813–1897).

Carlyle was brought up as a strict Calvinist and was educated at the village school. According to his biographer, Fred Kaplan: "As a boy he learned reading from his mother, arithmetic from his father; he attended a private school in Ecclefechan and then, at the age of six, the nearby Hoddam parish school. He immediately became the pride of the schoolmaster, the young person on whom approving adults and jealous schoolmates place the burden of differentness. For his parents that quality had its rightful place in the circle of tradition. If their son was to be a man of learning, he would be a minister of the Lord; within their society the alternative was either madness or apostasy." Carlyle later wrote: "A man's religion consists not of the many things he is in doubt of and tries to believe, but of the few he is assured of, and has no need of effort for believing".

In 1806 he entered Annan Academy, a school that specialized in training large classes, at low cost, for university entrance at the age of fourteen. At this time his best subject was mathematics but he also excelled in foreign languages. He received training in French and Latin but over the next few years taught himself Spanish, Italian, and German. Carlyle also took a keen interest in literature and read the work of Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Tobias Smollett, Laurence Sterne and William Congreve. He told Henry Fielding Dickens that he was a "gawky youth with a shock of red hair, and explained how he used to be bullied by other boys."

Carlyle was an excellent student and he won his place at the University of Edinburgh. In November 1809 he walked the 80 mile journey to Edinburgh. It took him three days and he later commented that by the beginning of the second day he had travelled further from Ecclefechan than his father was ever to do in his life. Carlyle was very unhappy in first year at university. His religious upbringing made it impossible for "him to participate" in the "amusements, too often riotous and libertine" of the other students.

Carlyle's father expected him to attend divinity school after completing his university studies. However, he rejected this idea and in 1814 became a mathematics teacher at Annan Academy at £70 per annum. In 1816 he obtained a teaching position at Kirkcaldy where he taught Latin, French, arithmetic, bookkeeping, geometry, navigation and geography. In November 1818, suffering from depression, Carlyle resigned and returned to Edinburgh.

In late May 1821 met the recently widowed Grace Welsh (1782–1842) and her nineteen-year-old daughter Jane Baillie Welsh. Carlyle was immediately impressed with Jane and described her as a "tall aquiline figure, of elegant carriage and air". According to Fred Kaplan, the author of Thomas Carlyle: A Biography (1983): "Carlyle spoke that evening of his own reading, writing, and literary ambitions. Jane listened intently, impressed by his learning and amused by his Annandale accent and country awkwardness.... Frightened of marriage because, among other reasons, she was frightened of sex, Jane Welsh could not imagine that such a man could become her husband." However, she was willing to read the articles he was writing and came to the conclusion that he was a "genius".

Although he disliked teaching, Carlyle agreed to tutor the two sons of Isabella and Charles Buller, on the rather generous sum of £200 per annum, about twice as much as his father had ever earned as a stonemason. In the spring of 1823 Carlyle was commissioned to write a short biographical sketch of Friedrich Schiller for The London Magazine. He was also an expert on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and in 1824 he completed a translation of Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship. Later that year he moved to London where he associated with Charles Lamb, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Henry Crabb Robinson.

After much prevarication Jane Welsh agreed to marry Thomas Carlyle. The wedding took place on 17th October 1826. Fred Kaplan has argued: "Clearly, puritanical inhibitions and romantic idealizations were in the 7 foot-wide bed with two sexual innocents. Fragile evidence suggests that though they were able to express affection with whispers and embraces their sexual relationship did not provide physical satisfaction to either of them, despite their efforts during the first half-dozen or so years of the marriage." Carlyle's biographer James Anthony Froude has argued that the marriage was unconsummated.

The couple settled in Craigenputtock. He told his friend, Thomas Story Spedding: "It is one of the most unoccupied, loneliest, far from one of the joyfullest of men. From time to time I feel it absolutely necessary to get into entire solitude; to beg all the world, with passion if they will not grant it otherwise, to be so kind as to leave me altogether alone. One needs to unravel and bring into some articulation the villainous chaos that gathers round heart and head in that loud-roaring Babel; to repent of one's many sins, to be right miserable, humiliated, and do penance for them - with hope of absolution, of new activity and better obedience!"

Thomas Carlyle appeared to hold his wife in great esteem. He later wrote: "She could do anything well to which she chose to give herself.... She had a keen clear incisive faculty of seeing through things, and hating all that was make-believe or pretentious. She had good sense that amounted to genius. She loved to learn and she cultivated all her faculties to the utmost of her power. She was always witty … in a word she was fascinating and everybody fell in love with her."

Thomas Carlyle's reputation as an expert on literature and philosophy resulted in him receiving commissions from The Edinburgh Review and The Foreign Review. He also started work on his first book, Sartor Resartus. However, he had great difficulty finding someone willing to publish this philosophical work. It eventually was serialized in Fraser's Magazine (1833-34).

Thomas and Jane Carlyle moved to London. He developed a close friendship with John Stuart Mill and he had several articles published in his Westminster Review. Mill was very close to Harriet Taylor, who was married to Henry Taylor. In 1833 Harriet negotiated a trial separation from her husband. She then spent six weeks with Mill in Paris. On their return Harriet moved to a house at Walton-on-Thames where John Stuart Mill visited her at weekends. Although Harriet Taylor and Mill claimed they were not having a sexual relationship, their behaviour scandalized their friends. As a result, the couple became socially isolated. However, Carlyle stood by Mill.

It was Mill who suggested that Carlyle should write a book about the French Revolution. He agreed and started the book in September 1834. After completing the first volume he sent it to Mill for his comments. On the night of 6th March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's house with the news that the manuscript had been burnt by mistake at the home of Harriet Taylor. The following day he decided to rewrite volume one again. The three volume book was not finished until 12th January, 1837. Ralph Waldo Emerson arranged for it to be published in America.

John Stuart Mill was active in the campaign for parliamentary reform, and was one of the first to suggest that women should have the same political rights as men. He introduced Carlyle to other political radicals such as Frederick Denison Maurice, Harriet Martineau, James Leigh Hunt, Robert Southey and William Wordsworth.

Mill urged Carlyle to write a pamphlet about parliamentary reform. In March 1838 he wrote: "Unluckily or luckily this notion of writing on the Working Classes has in the interim died away in me; and I have altogether lost it for the present. I have got upon Thuycidides, Johannes Müller, the Crusades, and a whole course of objects connected with my Lectures; sufficient to occupy me abundantly till that fatal time come. We will commit my Discourse on the Working Classes once more to the chapter of chances. I do not know that my train of argument would have specially led me to insist on the question you allude to: but if it had - ! In fact it were a right cheerful thing for me could I get to see that general improvement were going on there; and I think I should in that case wash my hands of Radicalism forever and a day." Carlyle was disturbed by the fact that working-class leaders such as Francis Place disagreed with his approach to the subject. Carlyle wrote: "Francis Place is against me, a man entitled to be heard."

Carlyle was opposed to Physical Force Chartism. In 1839 he wrote to his friend, Thomas Story Spedding: "What you say of Chartism is the very truth: revenge begotten of ignorance and hunger! We have enough of it here too; the material of it exists I believe in the hearts of all our working population, and would right gladly body itself in any promising shape; but Chartism begins to seem unpromising. What to do with it? Yes, there is the question. Europe has been struggling to give some answer, very audibly since the year 1789! The gallows and the bayonet will do what they can; these altogether failing, we may hope a quite other sort of exorcism will be tried.... Unless gentry, clergy and all manner of washed articulate-speaking men will learn that their position towards the unwashed is contrary to the Law of God, and change it soon, the Law of Man, one has reason to discern, will change it before long, and that in no soft manner.... The fever-fit of Chartism will pass, and other fever-fits; but the thing it means will not pass, till whatsoever of truth and justice lies in the heart of it has been fulfilled; it cannot pass till then, a long date, I fear."

Carlyle met Charles Dickens for the first time in 1840. Carlyle described Dickens as "a fine little fellow... a face of most extreme mobility, which he shuttles about - eyebrows, eyes, mouth and all - in a very singular manner while speaking... a quiet, shrewd-looking, little fellow, who seems to guess pretty well what he is and what others are." The two men became close friends. Dickens told one of his sons that Carlyle was the man "who had influenced him most" and his sister-in-law, that "there was no one for whom he had a higher reverence and admiration".

Carlyle published Chartism in 1841. He argued the immediate answers to poverty and overpopulation was improved education and an expansion of emigration. This position angered many of his radical friends. Other books by Carlyle during this period included On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History (1841) and Past and Present (1843).

Thomas Carlyle highly disapproved of the industrial revolution. Something he called the "Mechanical Age". In 1842 he described his first journey on a steam locomotive: "I was dreadfully frightened before the train started; in the nervous state I was in, it seemed to me certain that I should faint, from the impossibility of getting the horrid thing stopped."

The literary critic, Richard Hengist Horne, was one of the first people to champion the writing of Carlyle. He argued in A New Spirit of the Age (1844): "Mr. Carlyle... has knocked out his window from the blind wall of his century... We may say, too, that it is a window to the east; and that some men complain of a certain bleakness in the wind which enters in at it; when they should rather congratulate themselves with him on the aspect of the new sun beheld through it, the orient of hope of which he has discovered to their eyes." James Fitzjames Stephen was another supporter of Carlyle: "Regarded as works of art, we should put the best of Mr. Carlyle's writings at the very head of contemporary literature… If he is the most indignant and least cheerful of living writers, he is also one of the wittiest and the most humane." Peter Ackroyd has argued that "there is a strong case to be made for Carlyle being the single most important writer in England during the 1840s"

Andrew Sanders has argued: "What the early Victorians most admired in Carlyle was his ability to disturb them. It was he who seemed to have identified the nature of their restlessness and who had put his finger on the racing pulse of the age.... Carlyle was, and remains, an uncomfortable and disconcerting writer: edgy, prickly, experimental, challenging. He seems, by turns, to be persuasively sophisticated and provocatively direct. He was an outsider to mainstream early Victorian culture in two ways: he had been born in the same year as John Keats and was approaching 40 when he moved to London; he was also, by origin, a poor Scot who had been educated at the University in Edinburgh which still basked in the afterglow of the Scottish Enlightenment."

Carlyle was always concerned about his health but it was Jane who was constantly unwell. She wrote to a friend that she was "suffering from a bad nervous system, keeping me in a state of greater or less physical suffering". Thomas Carlyle, wrote to Catherine Dickens on 24th April, 1843: "We are such a pair of poor sickly creatures here, we have to deny ourselves the pleasure of dining out anywhere at present; and, I may well say with very great reluctance, even that of dining at your house on Saturday, one of the agreeablest dinners that human ingenuity could propose for us!"

Carlyle became a friend of Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary, and they had long discussions on parliamentary reform. Jane Carlyle and Mazzini developed an increasing intimate relationship. In 1846 Jane considered leaving her husband over his platonic relationship with Lady Harriet Baring, the wife of Bingham Baring, 2nd Baron Ashburton, but Mazzini strongly advised her not to.

After the Revolutions of 1848, Carlyle developed reactionary views. In 1850 he wrote a series of twelve pamphlets to be published in monthly installments over the next year. In Latter-Day Pamphlets he attacked democracy as an absurd social ideal and commented that it was absurd that "truth could be discovered by totting up votes". However, at the same time Carlyle criticized hereditary aristocratic leadership as "deadening". Carlyle suggested that people should be ruled by "those most able". Although Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels agreed with Carlyle about aristocratic leadership, they completely rejected his ideas on democracy.

In 1854 Charles Dickens dedicated his book, Hard Times to Carlyle. He also helped Dickens with his book, A Tale of Two Cities (1859). Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990), has pointed out: "He (Dickens) had always admired Carlyle's History of the French Revolution, and asked him to recommend suitable books from which he could research the period; in reply Carlyle sent him a cartload of volumes from the London Library. Apparently Dickens read, or at least looked through, them all; it was his aim during the period of composition only to read books of the period itself."

On 21st April 1866, Jane Carlyle went for her regular afternoon carriage ride in Hyde Park. Thomas Carlyle's biographer, Fred Kaplan, argues that "after several circuits of the park the driver, alarmed by Mrs Carlyle's lack of response to his request for further instructions, asked a woman to look into the carriage." According to the witness she "was leaning back in one corner of the carriage, rugs spread over her knees; her eyes were closed, and her upper lip slightly, slightly opened".

Henry Fielding Dickens visited him during this period: "It was my privilege to pay him two or three visits at his house in Cheyne Row after my father's death. I went there for the first time with feelings of awe and some trepidation. This was but natural in the case of a very young man paying a visit to an old man of Carlyle's rare gifts and immense reputation, and one who could be very dour at times. But I found that such feeling was quite uncalled for and he at once put me entirely at my ease. He was gifted with a high sense of humour, and when he laughed he did so heartily, throwing his head back and letting himself go."

Carlyle's early articles inspired social reformers such as John Ruskin, Charles Dickens, John Burns, Tom Mann and William Morris. However, in later life he turned against all political reform and argued against the 1867 Reform Act. He also expressed his admiration for strong leaders. This is illustrated by his six volume History of Frederick the Great (1858-1865) and The Early Kings of Norway (1875). In the last few years of his life, Carlyle's writing was confined to letters to The Times.

Thomas Carlyle died at his home at 5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, on 5th February, 1881.

On this day in 1890 Kurt Lüdecke was born in Berlin. He came from a wealthy background and was well-educated and spoke several foreign languages and travelled widely in his youth. Lüdecke had a private income and did not have to earn a living.

Lüdecke saw Adolf Hitler speak on 11th August 1922. He later recalled: "I studied this slight, pale man, his brown hair parted on one side and falling again and again over his sweating brow. Threatening and beseeching, with small pleading hands and flaming steel-blue eyes, he had the look of a fanatic. Presently my critical faculty was swept away he was holding the masses, and me with them, under a hypnotic spell by the sheer force of his conviction."

The following day, Lüdecke joined the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Lüdecke considered the Sturmabteilung (SA) as "little better than gangs". He approached Hitler and suggested that he should form an elite, well-disciplined company of Storm Troopers. He thought that their example might prove an inspiration to the rest of the SA. Hitler agreed and as James Pool points out: "Lüdecke began recruiting, accepting only the toughest and most able-bodied men who had either served in the war or had some military training. Two former Army officers were appointed as platoon leaders. A number of young students began to join the troop. A band with four drummers and four fifers was organized. Drills were held regularly. Every Wednesday night the entire company would assemble in a room Lüdecke had rented in a cafe on Schoenfeldstrasse, where he lectured his men on the political aims of the Nazi Party. Every new member took an oath of allegiance on the swastika flag and pledged loyalty to Hitler."

Lüdecke also bought the uniforms and other equipment for the men. Except for a few small details, the appearance of Lüdecke's men was almost indistinguishable from regular Army troops. Their uniform consisted of Army tunic, military breeches, Austrian ski-caps, leggings, and combat boots. each man also wore a leather belt and a swastika armband. By the end of December 1922 about 100 men. Lüdecke a close friend of Ernst Roehm had managed to help him obtain 15 heavy Maxim guns, more than 200 hand grenades, 175 rifles and thousands of rounds of ammunition. According to Lüdecke's own account, he earned the money to finance his S.A. troop by selling treadless tires to the Russian government.