On this day on 29th November

On the day in 1530 Thomas Wolsey, English cardinal, died. In 1527 Henry VIII sent a message to the Pope Clement VII arguing that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon had been invalid as she had previously been married to his brother Arthur. Henry relied on Thomas Wolsey to sort the situation out. Wolsey visited Pope Clement, who had fled to Orvieto to escape from King Charles V. Clement pleaded ignorance of canon law. One of Wolsey's ambassadors told him that the "whole of canon law was locked in the bosom of his Holiness". Pope Clement replied, "It may be so, but, alas, God has forgotten to give me the key to open it."

On 13th April 1528, Pope Clement appointed Cardinal Wolsey and Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggi to examine all the facts and pass a verdict without possibility of appeal. Wolsey wrote to Campeggi and pleaded with him to visit London to sort the matter out: "I hope all things shall be done according to the will of God, the desire of the king, the quiet of the kingdom, and to our honour."

Campeggi eventually arrived in England on 8th October 1528. He informed Wolsey that he had been ordered by Pope Clement not to do anything that would encourage King Charles V of Spain to attack Rome. He therefore ordered Campeggi to do all in his power to reconcile Henry and Catherine. If this was not possible, he was to use delaying tactics.

Campeggi visited Catherine of Aragon. She claimed that she had shared a bed on only seven occasions, and at no time had Prince Arthur "known" her. She was therefore the legitimate wife of Henry VIII because at the time of their marriage she was "intact and uncorrupted". Campeggi suggested that she took a vow of "perpetual chastity" and enter a convent and submit to a divorce. She rejected this idea and said she intended to "live and die in the estate of matrimony, into which God had called her, and that she would always be of that opinion and never change it". Campeggi reported that "although she might be torn limb by limb" nothing would "compel her to alter this opinion." (79) However, she was "an obedient daughter of the Church" and she "would submit to the Pope's judgement in the matter and abide by his decision, whichever way it might go".

According to a letter he sent to Pope Clement VII, Campeggi claims that Wolsey was "not in favour of the affair" but "dare not admit this openly, nor can he help to prevent it; on the contrary he has to hide his feelings and pretend to be eagerly pursuing when the king desires." Wolsey admitted to Campeggi "I have to satisfy the king, whatever the consequences.

On 25th January, 1529, Jean du Bellay told King François I that "Cardinal Wolsey... is in grave difficulty, for the affair has gone so far that, if it do not take effect, the King his master will blame him for it, and terminally". Du Bellay also suggested that Anne Boleyn was plotting against Wolsey who was in dispute with Sir Thomas Cheney. He pointed out that Cheney "had given offence" to Wolsey "within the last few days, and, for that reason, had been expelled from the Court." However, "the young lady (Boleyn) has put Cheney in again."

As David Starkey has pointed out: "Hitherto, whatever Anne may have thought about Wolsey in private, her public dealings with him had been correct, even warm. Now she had broken with him with deliberate, public ostentation. It can only have been because she had decided that his initiatives in Rome were doomed to failure... For the King, formally at least, was giving his full backing to his minister. Who would be proved right: the mistress or the minister? And where would that leave Henry?"

Lorenzo Campeggi's biographer, T. F. Mayer, claims that Henry VIII tried to bribe him by promising him the bishopric of Durham, but he could not find a way of persuading Catherine to change her mind. After several months of careful diplomatic negotiation a trial opened at Blackfriars on 18th June 1529 to prove the illegality of the marriage. It was presided over by Campeggi and Wolsey. Henry VIII ordered Catherine to choose the lawyers who would act as her counsel. He said she could pick from the best in the realm. She choose Archbishop William Warham and John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester.

Catherine of Aragon made a spirited defence of her position. George Cavendish was an eyewitness in the court. He quotes her saying: "Sir, I beseech you, for all the loves that hath been betrayed us, and for the love of God, let me have justice and right. Take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman and a stranger born out of your dominion. I have here no assured friend, and much less indifferent counsel. I flee to you as the head of justice within this realm. Alas, Sir, where have I offended you? Or what occasion have you of displeasure, that you intend to put me from you? I take God and all the world to witness that I have been to you a true, humble and obedient wife, ever conformable to your will and pleasure. I have been pleased and contented with all things wherein you had delight and dalliance. I never grudged a word or countenance, or showed a spark of discontent. I loved all those whom you loved only for your sake, whether I had cause or no, and whether they were my friends or enemies. This twenty years and more I have been your true wife, and by me you have had many children, though it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no fault in me."

The trial was adjourned by Campeggi on 30th July to allow Catherine's petition to reach Rome. With the encouragement of Anne Boleyn, Henry became convinced that Wolsey's loyalties lay with the Pope, not England, and in 1529 he was dismissed from office. Wolsey blamed Anne for his situation and he called her "the night Crow" who was always in a position to "caw into the king's private ear".

Wolsey's palaces and colleges were confiscated by the crown as a punishment for his offences, and he retired to his home in York. He began secretly negotiating with foreign powers in an attempt to get their support in persuading Henry to restore him to favour. His leading advisor, Thomas Cromwell, warned him that his enemies knew what he was doing. He was arrested and charged with high treason.

Thomas Wolsey had been in poor health for several years. Portraits show that he was grossly overweight and his biographer, Sybil M. Jack, suggested he might have been suffering from diabetes. "Doctors knew at least some of the dietary measures which could help to control it. They also knew that failure to eat regularly was dangerous. Wolsey's refusal to eat after his arrest, and his subsequent dysentery and vomiting, are reported by the Venetian ambassador." Wolsey died before he could be brought to trial.

On this day in 1790, A Vindication of the Rights of Man by Mary Wollstonecraft is published anonymously. In November, 1789, Richard Price preached a sermon praising the revolution. Price argued that British people, like the French, had the right to remove a bad king from the throne. "I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; a general amendment beginning in human affairs; the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priest giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience."

Edmund Burke, was appalled by this sermon and wrote a reply called Reflections on the Revolution in France where he argued in favour of the inherited rights of the monarchy. He also attacked political activists such as Major John Cartwright, John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Thomas Walker, who had formed the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation that promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform.

Burke attacked the dissenters who were wholly "unacquainted with the world in which they are so fond of meddling, and inexperienced in all its affairs, on which they pronounce with so much confidence". He warned reformers that they were in danger of being repressed if they continued to call for changes in the system: "We are resolved to keep an established church, an established monarchy, an established aristocracy, and an established democracy; each in the degree it exists, and in no greater."

Joseph Priestley was one of those attacked by Burke, pointed out: "If the principles that Mr Burke now advances (though it is by no means with perfect consistency) be admitted, mankind are always to be governed as they have been governed, without any inquiry into the nature, or origin, of their governments. The choice of the people is not to be considered, and though their happiness is awkwardly enough made by him the end of government; yet, having no choice, they are not to be the judges of what is for their good. On these principles, the church, or the state, once established, must for ever remain the same." Priestley went on to argue that these were the principles "of passive obedience and non-resistance peculiar to the Tories and the friends of arbitrary power."

Mary Wollstonecraft also felt that she had to respond to Burke's attack on her friends. Joseph Johnson agreed to publish the work and decided to have the sheets printed as she wrote. According to one source when "Mary had arrived at about the middle of her work, she was seized with a temporary fit of topor and indolence, and began to repent of her undertaking." However, after a meeting with Johnson "she immediately went home; and proceeded to the end of her work, with no other interruption but what were absolutely indispensable".

The pamphlet A Vindication of the Rights of Man not only defended her friends but also pointed out what she thought was wrong with society. This included the slave trade and way that the poor were treated. In one passage she wrote: "How many women thus waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practised as physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, supported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads surcharged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to which it at first gave lustre."

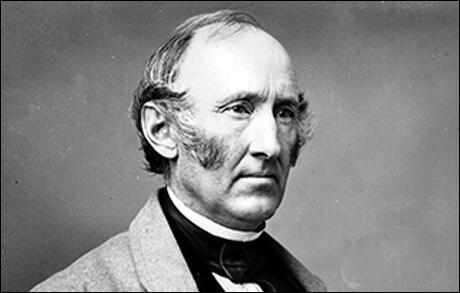

On the day in 1811 Wendell Phillips was born. Educated at the Harvard Law School, he open a law office in Boston in 1834. Phillips was converted to the abolition of slavery cause when he heard William Lloyd Garrison speak at the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1835. Phillips was particularly impressed by the bravery of these people and during the meeting a white mob attempted to lynch Garrison. Phillips was so outraged by what he saw that he decided to give up law and devote himself to obtaining the freedom of all slaves.

Phillips became a leading figure in the Anti-Slavery Society. A magnificent orator, Phillips was the society's most popular public speaker. Phillips also contributed to Garrison's The Liberator and wrote numerous pamphlets on slavery.

During the Civil War, Phillips criticised Abraham Lincoln for his lack of commitment to the abolition of slavery. In 1865 Phillips replaced Garrison as president of the Anti-Slavery Society. After the passing of the 15th Amendment, Phillips concentrated on other issues such as universal suffrage, women's rights, and temperance. Wendell Phillips died in Boston on 2nd February, 1884.

On this day in 1825 Jessie Boucherett, the daughter of Frederick John Pigou, was born at North Willingham, near Market Rasen. Her father had been High Sheriff of Lincolnshire in 1820.

Boucherett was educated at the school run by the Byerley sisters at Avonbank, Stratford upon Avon, where Elizabeth Gaskell had been a pupil and where the curriculum included the works of women writers of the day. She was also influenced by the work of Harriet Martineau.

According to Helen Blackburn Boucherett purchased a copy of English Woman's Journal at a railway bookstall. In June 1859 she visited the journal office in London and became friendly with Bessie Rayner Parkes and Barbara Bodichon. This resulted in the women forming the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. They also persuaded Lord Shaftesbury to became the society's first president. As her biographer, Linda Walker, pointed out: "Supported by her private income and surrounded by like-minded new friends, Boucherett subsequently devoted much of her life to the cause of women's emancipation." In 1863 Jessie Boucherett published Hints for Self-Help: a Book for Young Women.

In 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse."

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group eventually included Jessie Boucherett, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Louisa Smith, Alice Westlake, Katherine Hare, Harriet Cook, Helen Taylor, Emily Faithfull, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy and Elizabeth Garrett.

On 21st November 1865, the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The question was: "Is the extension of the Parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?. Both Barbara Bodichon and Helen Taylor submitted a paper on the topic. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

The women took their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." Mill added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men but it was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. John Stuart Mill became president and other members included Helen Taylor, Frances Power Cobbe, Lydia Becker, Millicent Fawcett, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Lilias Ashworth Hallett, Louisa Smith, Alice Westlake, Katherine Hare, Harriet Cook, Catherine Winkworth, Kate Amberley, Elizabeth Garrett, Priscilla Bright McLaren and Margaret Bright Lucas.

Mentia Taylor agreed to be secretary of the London Society for Women's Suffrage. On 15th July 1867 she wrote to Helen Taylor that "Our present course of action is the dissemination of information throughout the kingdom and it seems to me, we cannot apply our pounds to better purpose than by the publication of good papers." The following year the LSWS reprinted as a pamphlet, an article written by Harriet Taylor, The Enfranchisement of Women.

The London Society for Women's Suffrage held several meetings every year. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "In the year 1875-76 the London National Society appears to have held three public meetings, four at working men's clubs, and 13 drawing-room meetings." Crawford points out that at one of these meetings held at St Pancras it was made clear that "the object of the society is to obtain the parliamentary franchise for widows and spinsters on the same conditions as those on which it is granted to men."

Lydia Becker became secretary of the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage in 1881. Other members of the executive committee included Jessie Boucherett, Helen Blackburn, Frances Power Cobbe, Millicent Fawcett, Margaret Bright Lucas, Eva Maclaren, Priscilla Bright McLaren, Helen Taylor and Katherine Thomasson.

By the 1890s there were seventeen individual groups that were advocating women's suffrage. This included the London Society for Women's Suffrage, Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage and the Central Committee for Women's Suffrage. On 14th October 1897, these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Lydia Becker was elected as president and Boucherett joined the executive committee of the NUWSS.

Jessie Boucherett died from liver cancer on 18th October 1905 at Willingham House. Her estate was assessed at over £39,000. She left £2,000 to the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, £2,000 to the Freedom of Labour Defence Society, £500 to the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection and £500 to the English Woman's Journal.

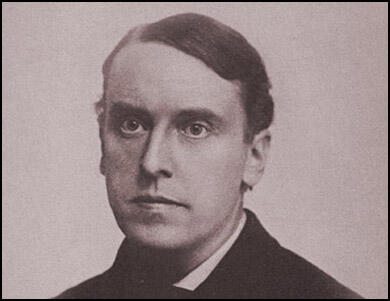

On the day in 1849 Edward Aveling, the son of a Congregational minister, was born in Stoke Newington, London. Aveling was educated at Harrow School and the Faculty of Medicine at University College, London. An excellent student and after he graduated he was appointed as a Lecturer in Comparative Anatomy at London Hospital.

Aveling was influenced by the theories of Charles Darwin and lost his religious beliefs. He joined the Secular Society and became friendly with Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant. Aveling contributed articles on scientific subjects to Bradlaugh's journal, The National Reformer and wrote a book on evolution called The Student's Darwin (1881). Aveling's public statements on his atheism resulted in him being removed from his post at London Hospital.

Annie Besant was impressed by Aveling's ability to communicate complex subjects and she organised a series of Sunday lectures on science and religion throughout Britain. Aveling also helped Charles Bradlaugh in his struggle to be allowed to take his seat in the House of Commons after he was elected to represent Northampton in the 1880 General Election.

In 1881 Aveling met Charles Darwin and had several long meetings with him about science and religion. Aveling published the results of these discussions in a book The Religious Views of Charles Darwin. Controversially, Aveling claimed in his book that Darwin was a atheist.

Annie Besant introduced Aveling to H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). When Aveling was a candidate for the London School Board elections in November, 1882, members of both the Secular Society and the SDF campaigned for him. Aveling, whose main policy was the free, elementary schooling for the working class, was elected to the School Board.

Some members of the Secular Society and the Social Democratic Federation, disapproved of Aveling's moral behaviour. Aveling, who had married Isabel Frank in 1872, had a number of sexual relationships with women, including Annie Besant and Eleanor Marx. In 1883 Aveling and Marx began to live together. Although Marx saw this as the same as if someone was officially married, Aveling continued to have affairs with other women.

Aveling became a member of the SDF but disagreed with H. H. Hyndman about a wide range of different issues. At a SDF meeting on 27th December, 1884, the executive voted by a majority of two (10-8), that it had no confidence in Hyndman. When Hyndman refused to resign, some members, including Aveling, William Morris, and Eleanor Marx left the party and formed a new organisation called the Socialist League. Aveling also worked closely with Morris to produce the Socialist League's journal, Commonweal.

Aveling helped translate Das Kapital into English and co-authored The Woman Question (1886) with Eleanor Marx. Aveling was an unpopular figure in the Socialist League and after one dispute in May 1886 he left the organisation. Later that year Aveling and Marx went on a tour of the United States organised by the Socialist Party of America. Although the couple drew large crowds, Aveling became involved in a conflict with party leaders over what they considered to be his extravagant claims for expenses.

When Edward Aveling returned to England he joined with Friedrich Engels to form a new Marxist working class party. However, by this time, Aveling was completely distrusted by socialists in Britain and received little support for the venture.

Disillusioned with politics, Edward Aveling became a playwright. Four of his plays were performed but none of them were successful. Aveling also joined with Eleanor Marx to put on Henrik Ibsen's play, A Doll's House. The production was attacked by critics who claimed that it was "destructive of family life".

In 1895, Aveling became seriously ill with kidney disease and Eleanor spent many months nursing him back to health. After Aveling recovered he left Eleanor and moved in with Eva Frye, a 22 year old actress. However, after a few months, Aveling, who was deeply in debt, returned to Eleanor who had recently been left money by Engels.

Aveling became ill again in 1898 and had to have major surgery. Eleanor Marx once again had the job of looking after him. Soon after he recovered, Aveling told Eleanor that he had secretly married Eva Frye and was returning to her. Unable to bear the pain of this latest betrayal, Eleanor committed suicide on 31st March, 1898. Edward Aveling, who was now completely ostracized by the labour movement, had a relapse and died on 2nd August, 1898.

On the day in 1857 the Reynolds News publishes an account of Saltaire. In 1833 Titus Salt took over the running of the company. Over the next twenty years Salt became the largest employer in Bradford. Between 1801 and 1851 the population of Bradford grew from 13,000 to 104,000. With over 200 factory chimneys continually churning out black, sulphurous smoke, Bradford gained the reputation of being the most polluted town in England. Bradford's sewage was dumped into the River Beck. As people also obtained their drinking water from the river, this created serious health problems. There were regular outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, and only 30% of children born to textile workers reached the age of fifteen. Life expectancy, of just over eighteen years, was one of the lowest in the country.

George Weerth visited Bradford in 1846: "Every other factory town in England is a paradise in comparison to this hole. In Manchester the air lies like lead upon you; in Birmingham it is just as if you were sitting with your nose in a stove pipe; in Leeds you have to cough with the dust and the stink as if you had swallowed a pound of Cayenne pepper in one go - but you can put up with all that. In Bradford, however, you think you have been lodged with the devil incarnate. If anyone wants to feel how a poor sinner is tormented in Purgatory, let him travel to Bradford."

Titus Salt, who now owned five textile mills in Bradford, was one of the few employers in the town who showed any concern for this problem. After much experimentation, Salt discovered that the Rodda Smoke Burner produced very little pollution. In 1842 he arranged for these burners to be used in all his factories.

In 1848 Salt became mayor of Bradford. He tried hard to persuade the council to pass a by-law that would force all factory owners in the town to use these new smoke burners. The other factory owners in Bradford were opposed to the idea. Most of them refused to accept that the smoke produced by their factories was damaging people's health.

When Titus Salt realised the council was unwilling to take action, he decided to move from Bradford. In 1850, Salt announced his plans to build a new industrial community called Saltaire at a nearby beauty spot on the banks of the River Aire. Saltaire, which was three miles from Bradford, took twenty years to build. At the centre of the village was Salt's textile mill. The mill was the largest and most modern in Europe. Noise in the factory was reduced by placing underground much of the shafting which drove the machinery. Large flues removed the dust and dirt from the factory floor. To ensure that the neighbourhood did not suffer from polluted air, the mill chimney was fitted with Rodda Smoke Burners.

Sam Kydd wrote in the Reynolds News: "The site chosen for Saltaire is, in many ways, desirable. The scenery in the immediate neighbourhood is romantic, rural and beautiful. A better looking body of factory 'hands' than those in Saltaire I have not seen. They are far above the average of their class in Lancashire, and are considerably above the majority in Yorkshire."

At first Salt's 3,500 workers travelled to Saltaire from Bradford. However, during the next few years, 850 houses were built for his workers. Saltaire also had its own park, church, school, hospital, library and a whole range of different shops. The houses in Saltaire were far superior to those available in Bradford and other industrial towns. Fresh water was piped into each home from Saltaire's own 500,000 gallon reservoir. Gas was also laid on to provide lighting and heating. Unlike the people of Bradford, every family in Saltaire had its own outside lavatory. To encourage people to keep themselves clean, Salt also arranged for public baths and wash-houses to be built in Saltaire.

Titus Salt was also active in politics. Salt supported adult suffrage and did not believe that the 1832 Reform Act went far enough. In 1835 he was a founder of the Bradford Reform Association and publicly supported the Chartists. Disturbed by the growth of the Physical Force Chartists, Salt helped establish the United Reform Society, an attempt to unite middle and working class reformers.

Titus Salt was a severe critic of the 1834 Poor Law. He also supported the move to reduce working hours and was the first employer in the Bradford area to introduce the ten hour day. However, Salt held conservative views on some issues. He refused permission for his workers to join trade unions and disagreed with those like Richard Oastler and John Fielden who wanted Parliament to pass legislation on child labour. Salt employed young children in his factories and were totally opposed to the 1833 Factory Act that attempted to prevent children under the age of nine working in textile mills.

Salt gave his support to the Radical candidate in Bradford's parliamentary elections. However, at the request of the local Chamber of Commerce, Salt became a candidate in the 1859 General Election. Salt was elected but after two years in the House of Commons he resigned because of ill-health.

Titus Salt died on 29th December, 1876. Although he had been an extremely rich man, his family was horrified that his fortune was gone. It has been estimated that during his life he had given away over £500,000 to good causes. On his death The Bradford Observer commented: "Titus was perhaps the greatest captain of industry in England not only because he gathered thousands under him but also because, according to the light that was in him, he tried to care for all those thousands. We do not say that he succeeded in realising all his views or that it is possible to harmonise at present all relations between capital and labour. Upright in business, admirable in his private relations he came without seeking the honour to be admittedly the best representative of the employer class in this part of the country if not the whole kingdom."

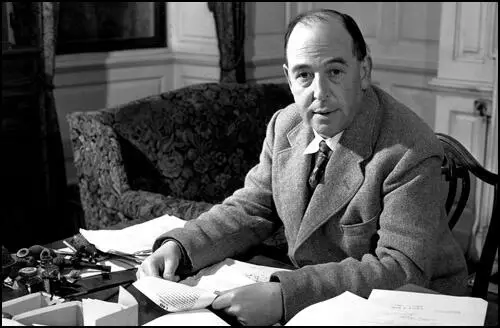

On the day in 1898 Clive Staples Lewis, the son of Albert Lewis, a successful solicitor, was born in Belfast. He had a brother, Warren Lewis and the two boys were initially taught at home by his mother, Flora Lewis, and a governess. Lewis later recalled that his family had a large library: "I took volume after volume from the shelves. I had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks in a field has of finding a new blade of grass".

In 1908 Lewis was sent away to join his brother at Wynyard School in Watford. Soon afterwards his mother died of cancer. He was very unhappy at the school and complained about the vicious and sadistic headmaster, Robert Capron. The school was eventually closed and Capron was committed to an insane asylum. Lewis moved to a preparatory school in Malvern.

Lewis attended Malvern College and in 1916 he won a scholarship to University College, Oxford. However, the Master of the College informed Lewis that, with the exception of one boy with health problems, everyone who had won a scholarship had joined the British Army in order to fight in the First World War. As the authors of Famous 1914-1918 (2008) pointed out: "As as Irishman, Lewis could legally have avoided service, there being no conscription in Ireland, but the thought never entered his head: he would serve."

Lewis initially joined a cadet battalion at Keble College. He made friends with a small group of students including Ernest Moore, Martin Somerville and Alexander Sutton. Lewis became a commissioned officer in the Somerset Light Infantry. He soon became very close to Laurence Johnson, who had also won a scholarship to Oxford University.

Lewis joined the regiment on the Western Front in November 1917. At the time the battalion was in a quiet sector of the front-line and was primarily engaged in pumping and clearing out waterlogged trenches. As Lewis later pointed out: "Through the winter, weariness and water were our chief enemies... One walked in the trenches in thigh gumboots with water above the knee, and one remembers the icy stream welling up inside the boot when you punctured it on concealed barbed wire." Tiredness was another major problem. Lewis admitted that "I have gone to sleep marching and woken again and found myself marching still."

In January 1918 Lewis was devastated when he heard that his great friend Alexander Sutton had been killed. Three months later Ernest Moore also lost his life. John Howe later recalled: "I saw him fall with a wound in his leg. I stopped and bound up the wound. While I was binding up his leg, he got another bullet right through the head, which killed him instantly." Moore was posthumously awarded the Military Cross.

In March the German Army launched the Spring Offensive. This included an attack at Arras where Lewis was based. After the Germans gained ground the Somerset Light Infantry was ordered to counter-attack at Riez du Vinage on 14th April 1918.

At 6pm, the heavy artillery opened fire on the German-held village. At 6.30pm a creeping barrage began. The plan was that the men would follow behind the exploding shells, at the rate of 50 metres per minute. Sergeant Arthur Cook later pointed out: "One of the most extraordinary advertisements of look out we're coming I have witnessed in this war, in full view of the enemy; how they must have chuckled with glee." According to Cook, the "barrage moved too quick, leaving the enemy free to open up a devastating machine-gun fire on the target they had been waiting for."

One of those hit by the machine-gun fire during the attack was Lewis' great friend, Lieutenant Laurence Johnson. He was taken to the nearest Casualty Clearing Station but he died the following morning. Martin Somerville was killed soon afterwards.

Lewis was one of those men who reached Riez du Vinage. "I took about 60 prisoners - that is, I discovered to my great relief that the crowd of field-grey figures who suddenly appeared from nowhere, all had their hands up."

The German artillery then began shelling Riez du Vinage. One of these shells exploded close to Lewis and he was peppered with shrapnel. "Just after I was hit, I found (or thought I found) that I was not breathing and concluded that this was death. I felt no fear and certainly no courage. It did not seem to be an occasion for either." When Lewis regained consciousness he discovered that the man standing next to him, Sergeant Harry Ayres, had been killed by the same shell that had wounded him.

Lewis was able to crawl away and was picked up by two stretcher-bearers. He was taken to a Casualty Clearing Station but although badly wounded his life was not in danger. Lewis was sent back to a hospital in Bristol where he made a slow recovery. Just after he arrived he wrote a letter to his father: "Nearly all my friends in the Battalion are gone. Did I ever mention Johnson who was a scholar of Queen's? I had hoped to meet him at Oxford some day, and renew the endless talks that we had out there ...I had had him so often in my thoughts, had so often hit on some new point in one of our arguments, and made a note of things in my reading to tell him when we met again, that I can hardly believe he is dead. Don't you find it particularly hard to realise the death of people whose strong personality makes them particularly alive?"

Lewis remained in hospital until October, 1918 and was demobbed two months later. He never fully recovered from his wounds and suffered from headaches and breathing problems for the rest of his life. He also had recurring nightmares: "On the nerves there are... effects which will probably go with quiet and rest... nightmares - or rather the same nightmare over and over again."

In 1919 Lewis took up his scholarship to Oxford University where he read classics and philosophy. He went to live with Jane Moore, the mother of Ernest Moore. He therefore kept the promise he had made in 1917 that he would look after his mother if he was killed in the First World War.

In 1925 Lewis became a fellow of Magdalen College, where he soon developed a reputation as an outstanding teacher. He published a series of books on philosophy including The Pilgrim Regress (1933), and The Allegory of Love (1936). Lewis also produced a science fiction trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1939) and That Hideous Strength (1945).

Lewis continued to live with Jane Moore in an house at Headington, overlooking Oxford in the river valley below. Moore developed dementia after the Second World War and was eventually moved into a nursing home, where she died in 1951.

Lewis is best known for "Narnia" stories for children that began with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) and finished with The Last Battle (1956). One critic argued that these books combined "strong imagination and lively adventure with artfully concealed Christian parable".

In 1954 Lewis became Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English at Cambridge University. His autobiography, Surprised By Joy, was published in 1955.

For several years Lewis corresponded with Joy Davidman, an American poet. The couple were married on 21st March 1956. She died from bone cancer on 13th July, 1960. Lewis wrote about the relationship in his book, A Grief Observed (1961). Clive Staples Lewis died of kidney disease on 22nd November, 1963, the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

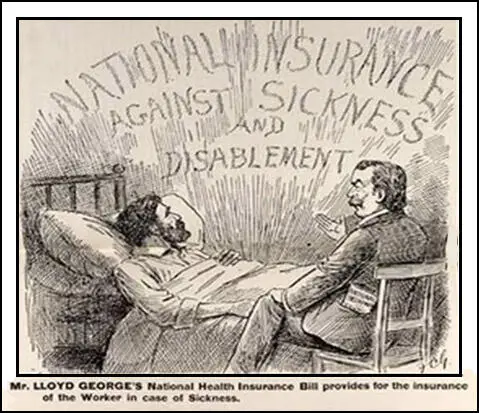

On the day in 1911 Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail, starts a campaign against the National Insurance Act. During his speech on the People's Budget, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, pointed out that Germany had a compulsory national insurance against sickness since 1884. He argued that he intended to introduce a similar system in Britain. With a reference to the arms race between Britain and Germany he commented: "We should not emulate them only in armaments."

In December 1910 Lloyd George sent one of his Treasury civil servants, William J. Braithwaite, to Germany to make an up-to-date study of its State insurance system. On his return he had a meeting with Charles Masterman, Rufus Isaacs and John S. Bradbury. Braithwaite argued strongly that the scheme should be paid for by the individual, the state and the employer: "Working people ought to pay something. It gives them a feeling of self respect and what costs nothing is not valued."

The slogan adopted by Lloyd George to promote the scheme was "9d for 4d". In return for a payment which covered less than half the cost, contributors were entitled to free medical attention, including the cost of medicine. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 10s. a week for thirteen weeks of sickness and 5s a week indefinitely for the chronically sick.

Braithwaite later argued that he was impressed by the way Lloyd George developed his policy on health insurance: "Looking back on these three and a half months I am more and more impressed with the Chancellor's curious genius, his capacity to listen, judge if a thing is practicable, deal with the immediate point, deferring all unnecessary decision and keeping every road open till he sees which is really the best. Working for any other man I must inevitably have acquiesced in some scheme which would not have been as good as this one, and I am very glad now that he tore up so many proposals of my own and other people which were put forward as solutions, and which at the time we had persuaded ourselves into thinking possible. It will be an enormous misfortune if this man by any accident should be lost to politics."

The large insurance companies were worried that this measure would reduce the popularity of their own private health schemes. Lloyd George, arranged a meeting with the association that represented the twelve largest companies. Their chief negotiator was Kingsley Wood, who told Lloyd George, that in the past he had been able to muster enough support in the House of Commons to defeat any attempt to introduce a state system of widows' and orphans' benefits and so the government "would be wise to abandon the scheme at once."

David Lloyd George was able to persuade the government to back his proposal of health insurance: "After searching examination, the Cabinet expressed warm and unanimously approval of the main and government principles of the scheme which they believed to be more comprehensive in its scope and more provident and statesmanlike in its machinery than anything that had hitherto been attempted or proposed."

The National Insurance Bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 4th May, 1911. Lloyd George argued: "It is no use shirking the fact that a proportion of workmen with good wages spend them in other ways, and therefore have nothing to spare with which to pay premiums to friendly societies. It has come to my notice, in many of these cases, that the women of the family make most heroic efforts to keep up the premiums to the friendly societies, and the officers of friendly societies, whom I have seen, have amazed me by telling the proportion of premiums of this kind paid by women out of the very wretched allowance given them to keep the household together."

Lloyd George went on to explain: "When a workman falls ill, if he has no provision made for him, he hangs on as long as he can and until he gets very much worse. Then he goes to another doctor (i.e. not to the Poor Law doctor) and runs up a bill, and when he gets well he does his very best to pay that and the other bills. He very often fails to do so. I have met many doctors who have told me that they have hundreds of pounds of bad debts of this kind which they could not think of pressing for payment of, and what really is done now is that hundreds of thousands - I am not sure that I am not right in saying millions - of men, women and children get the services of such doctors. The heads of families get those services at the expense of the food of their children, or at the expense of good-natured doctors."

Lloyd George stated this measure was just the start to government involvement in protecting people from social evils: "I do not pretend that this is a complete remedy. Before you get a complete remedy for these social evils you will have to cut in deeper. But I think it is partly a remedy. I think it does more. It lays bare a good many of those social evils, and forces the State, as a State, to pay attention to them. It does more than that... till the advent of a complete remedy, this scheme does alleviate an immense mass of human suffering, and I am going to appeal, not merely to those who support the Government in this House, but to the House as a whole, to the men of all parties, to assist us."

The Observer welcomed the legislation as "by far the largest and best project of social reform ever yet proposed by a nation. It is magnificent in temper and design". The British Medical Journal described the proposed bill as "one of the greatest attempts at social legislation which the present generation has known" and it seemed that it was "destined to have a profound influence on social welfare."

Ramsay MacDonald promised the support of the Labour Party in passing the legislation, but some MPs, including Fred Jowett, George Lansbury and Philip Snowden denounced it as a poll tax on the poor. Along with Keir Hardie, they wanted free sickness and unemployment benefit to be paid for by progressive taxation. Hardie commented that the attitude of the government was "we shall not uproot the cause of poverty, but we will give you a porous plaster to cover the disease that poverty causes."

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work."

Lloyd George pointed out that the labour movement in Germany had initially opposed national insurance: "In Germany, the trade union movement was a poor, miserable, wretched thing some years ago. Insurance has done more to teach the working class the virtue of organisation than any single thing. You cannot get a socialist leader in Germany today to do anything to get rid of that Bill... Many socialist leaders in Germany will say that they would rather have our Bill than their own." Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, launched a propaganda campaign against the bill on the grounds that the scheme would be too expensive for small employers. The climax of the campaign was a rally in the Albert Hall on 29th November, 1911. As Lord Northcliffe, controlled 40 per cent of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, 45 per cent of the evening and 15 per cent of the Sunday circulation, his views on the subject was very important.

H. H. Asquith was very concerned about the impact of the The Daily Mail involvement in this issue: "The Daily Mail has been engineering a particularly unscrupulous campaign on behalf of mistresses and maids and one hears from all constituencies of defections from our party of the small class of employers. There can be no doubt that the Insurance Bill is (to say the least) not an electioneering asset."

Frank Owen, the author of Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) suggested that it was those who employed servants who were the most hostile to the legislation: "Their tempers were inflamed afresh each morning by Northcliffe's Daily Mail, which alleged that inspectors would invade their drawing-rooms to check if servants' cards were stamped, while it warned the servants that their mistresses would sack them the moment they became liable for sickness benefit."

The National Insurance Bill spent 29 days in committee and grew in length and complexity from 87 to 115 clauses. These amendments were the result of pressure from insurance companies, Friendly Societies, the medical profession and the trade unions, which insisted on becoming "approved" administers of the scheme. The bill was passed by the House of Commons on 6th December and received royal assent on 16th December 1911.

Lloyd George admitted that he had severe doubts about the amendments: "I have been beaten sometimes, but I have sometimes beaten off the attack. That is the fortune of war and I am quite ready to take it. Honourable Members are entitled to say that they have wrung considerable concessions out of an obstinate, stubborn, hard-hearted Treasury. They cannot have it all their own way in this world. Let them be satisfied with what they have got. They are entitled to say this is not a perfect Bill, but then this is not a perfect world. Do let them be fair. It is £15,000,000 of money which is not wrung out of the workmen's pockets, but which goes, every penny of it, into the workmen's pocket. Let them bear that in mind. I think they are right in fighting for organisations which have achieved great things for the working classes. I am not at all surprised that they regard them with reverence. I would not do anything which would impair their position. Because in my heart I believe that the Bill will strengthen their power is one of the reasons why I am in favour of this Bill."

The Daily Mail and The Times, both owned by Lord Northcliffe, continued its campaign against the National Insurance Act and urged its readers who were employers not to pay their national health contributions. David Lloyd George asked: "Were there now to be two classes of citizens in the land - one class which could obey the laws if they liked; the other, which must obey whether they liked it or not? Some people seemed to think that the Law was an institution devised for the protection of their property, their lives, their privileges and their sport it was purely a weapon to keep the working classes in order. This Law was to be enforced. But a Law to ensure people against poverty and misery and the breaking-up of home through sickness or unemployment was to be optional."

Lloyd George attacked the newspaper baron for encouraging people to break the law and compared the issue to the foot-and-mouth plague rampant in the countryside at the time: "Defiance of the law is like the cattle plague. It is very difficult to isolate it and confine it to the farm where it has broken out. Although this defiance of the Insurance Act has broken out first among the Harmsworth herd, it has travelled to the office of The Times. Why? Because they belong to the same cattle farm. The Times, I want you to remember, is just a twopenny-halfpenny edition of The Daily Mail."

Despite the opposition from newspapers and and the British Medical Association, the business of collecting contributions began in July 1912, and the payment of benefits on 15th January 1913. Lloyd George appointed Sir Robert Morant as chief executive of the health insurance system. William J. Braithwaite was made secretary to the joint committee responsible for initial implementation.

On the day in 1935 Eleanor Rathbone makes an important speech on social reform. Rathbone was born in London on 12th May 1872. Her father, William Rathbone, a prosperous shipowner, came from a Quaker and Unitarian background. A supporter of the Liberal Party, William Rathbone served in the House of Commons from 1869 to 1895.

Rathbone was educated at home by a governess and private tutors before entering Somerville College, Oxford, in 1893. At university Rathbone became involved in the struggle to obtain women the vote and eventually became a leading figure in the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS).

After leaving university with a degree in philosophy, Rathbone became secretary of the Women's Industrial Council in Liverpool and was very involved in the organization's campaign against low pay and bad working conditions. In 1909 she became the first woman to be elected to Liverpool City Council and over the next few years argued for improved housing in the city.

Rathbone was elected to the executive committee of the NUWSS and led the opposition to the decision in 1912 to advise all members to campaign for the Labour Party in the general election. The following year she published her first book, The Condition of Widows under the Poor Law (1913).

During the First World War Rathbone established a committee to look into poverty in Britain. Members included Henry N. Brailsford, Maude Royden, Kathleen Courtney, Emile Burns and Mary Stocks. In 1917 the Family Endowment Committee published Equal Pay and the Family. A Proposal for the National Endowment of Motherhood. In the pamphlet Rathbone and her colleagues argued for the introduction of family allowances.

On the resignation of Millicent Fawcett in 1919, Rathbone became president of the NUWSS. She continued to campaign for social reform and in 1925 published her important book, The Disinherited Family. The following year the introduction of family allowances became a policy of the Independent Labour Party. However, the idea was rejected by the three major political parties.

In 1929 Rathbone was elected to the House of Commons as the Independent Member for the Combined British Universities. Over the next few years she campaigned against female circumcision in Africa, child marriage in India and forced marriage in Palestine. This included the publication of the book, Child Marriage: The Indian Minotaur (1934).

Eleanor Rathbone gave a speech at Bedford College on 29th November 1935: "There is a school of reformers which despises compromise. Suppose they set their affections on the moon. Their way is to go on chanting, 'We want the moon, we want the moon, we want the moon.' The plan which experience taught us was to begin by declaring, 'We want the moon,' but when certain that was unobtainable, to say firmly, 'If you can't give us the moon, give us that particular star, that big one'; if that failed, 'At least let us have that little star, just near the horizon. You know you can reach that one.' And when we got it, from the vantage ground of that little star, we proceeded to grasp at those nearest it. Or, to change the metaphor, there are reformers whose idea of taking a citadel is to march round it blowing trumpets, and when that fails, to batter it with rams, if necessary with their own heads. We sometimes used the battering ram, but if the wall proved too strong for us we withdrew a little and investigated every possible method of overcoming that wall, by climbing over it, or tunnelling under it or perhaps labouring to dislodge a stone at a time, so that just a few invaders could creep through. And we acquired by experience a certain flair which told us when a charge of dynamite would come in useful and when it was better to rely on the methods of the skilled engineer."

Rathbone also took a keen interest in foreign policy and was a strong opponent of the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War. In April 1937, Eleanor Rathbone, Ellen Wilkinson and the Duchess of Atholl travelled to Spain on a fact-finding mission. The party visited Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia and observed the havoc being caused by the Luftwaffe.

In May 1937 Rathbone joined with Charlotte Haldane, Duchess of Atholl, Ellen Wilkinson and J. B. Priestley to establish the Dependents Aid Committee, an organization which raised money for the families of men who were members of the International Brigades. Later she helped establish the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief.

Rathbone grew increasingly concerned about Adolf Hitler and his government in Nazi Germany. She totally opposed the British government's policy of appeasement and instead called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. These views were expressed in her book, War Can Be Averted (1937) and were officially supported by Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, David Lloyd George, Hugh Dalton and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

During the Second World War Rathbone continued to campaign for family allowances and in 1940 published The Case for Family Allowances. This became the policy of the Labour Party and her family allowances system was introduced in 1945. However, Rathbone was furious when she discovered that the allowance was to be paid to the father rather than the mother. This negated the feminist implications of the measure and she threatened to vote against the Bill. Eleanor Rathbone died of a heart-attack on 2nd January 1946.

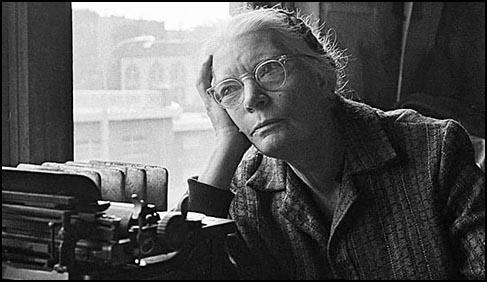

On the day in 1980 Dorothy Day died. Day was born in 1897. Her father John Day, was a journalist. In her autobiography, The Long Loneliness (1952) she recaled: "Being from Tennessee, he had the prevalent attitude of the South toward the Negro. He distrusted all foreigners and agitators... Probably his greatest unhappiness came from us whose ideas he did not understand and which he thought were subversive and dangerous to the peace of the country."

Dorothy's brother, Donald Day, began working for The Day Book, and at a penny a copy, it aimed for a working-class market, crusading for higher wages, more unions, safer factories, lower streetcar fares, and women’s right to vote. It also tackled the important stories ignored by most other dailies. According to Duane C. S. Stoltzfus, the author of Freedom from Advertising (2007): "The Day Book served as an important ally of workers, a keen watchdog on advertisers, and it redefined news by providing an example of a paper that treated its readers first as citizens with rights rather than simply as consumers."

Day later admitted that the newspaper informed her about people like Eugene Debs and organisations such as the Industrial Workers of the World: "Through the paper I learned of Eugene Debs, a great and noble labor leader of inspired utterance. There were also accounts of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World who had been organizing in their one great union so that there were a quarter of a million members throughout the wheatfields, mines, and woods of the Northwest, as well as in the textile factories in the East."

A favourite author of Day's was Peter Kropotkin. "Kropotkin especially brought to my mind the plight of the poor, of the workers, and though my only experience of the destitute was in books." Kropotkin introduced Day to anarchism. She also became very interested in the ideas of Francisco Ferrer, an anarchist who had been executed in Barcelona in 1909 and Emma Goldman, who at the time was was a great advocate of free love. Although she approved of Goldman's anarchism she was "revolted by such promiscuity".

Day was keen to become a journalist like her father and brothers. In June 1916 she found work with the socialist journal, the New York Call. Chester Wright initially paid her $5 a week but eventually raised it to $12. One of her assignments was to interview Leon Trotsky who was living in exile on the Lower East Side. Trotsky told her that "where parliamentarianism was weakest the socialist movement was the strongest". He thought the First World War would lead to revolution: "The social unrest after the war will eclipse anything the world has ever seen."

A fellow journalist at the newspaper was Michael Gold. He used to visit her in her room and the landlady notified her mother of "Dorothy's immoral conduct". Jim Forest argues in his biography of Day, Love is the Measure (1986): "It is not surprising that gossip about them continued to be plentiful. The two spent long hours walking the streets, sitting on piers along the waterfront on the East River, talking about life and sharing experiences about the passion that had brought them both to The Call - the sufferings of the poor."

On 2nd April 1917 Day resigned from New York Call. A few weeks later she joined The Masses, a radical journal edited by Max Eastman. The assistant editor, Floyd Dell, later recalled: "For a while my assistant on The Masses was Dorothy Day, an awkward and charming young enthusiast, with beautiful slanting eyes, who had been a reporter." Day became friendly with the talented John Reed: "He was a big, hearty Harvard graduate, a typical newspaperman, and very much the Richard Harding Davis reporter hero. Wherever there was excitement, wherever life was lived in high tension, there he was, writing, speaking, recording the moment, and heightening its intensity for everyone else."

Day was also a supporter of women's suffrage and worked closely with Alice Paul and Lucy Burns of the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS). The CUWS and attempted to introduce the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House. In November 1917, Day was one of the 168 women arrested and jailed for "obstructing traffic". The women went on hunger strike and afraid that martyrs would be created, Woodrow Wilson ordered their release.

Like most of the people working for The Masses, Day believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. When the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges.

In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp and articles by Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication.

Day now decided to leave journalism and she signed up for a nurse's training program in Brooklyn. She also began attending services at St. Joseph's Catholic Church. Day later explained that she saw the Catholic Church as the "church of the poor". Religion also helped her deal with the psychological problems caused by an abortion that she had during a love affair with a journalist. This experience provided the material for her autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924).

In December 1932 Day met Peter Maurin, a Christian Brother. They decided to establish the Catholic Worker, a newspaper to publicize Catholic social teaching. The first edition appeared on 1st May, 1933. The newspaper criticised the economic system and supported organisation such as trade unions that were attempting to create a more equal society. It also argued that the Catholic Church should be a pacifist organization. Day and Maurin believed the nonviolent way of life was at the heart of the Gospel.

The Catholic Worker became a vehicle for creating a national movement. By 1936 there were 33 Catholic Worker Houses spread out across the country. These were charitable, self-help communities for people suffering the effects of the Depression. Today there are 130 of these houses in 32 states and eight foreign countries.

The Catholic Worker encountered problems during the Spanish Civil War. Most Catholics in the United States supported the fascists and saw Franco as the defender of the Catholic faith. As pacifists, Day and Maurin refused to support either side. As a result the newspaper lost two-thirds of its readers.

Day also maintained her pacifism during the Second World War. This was an unpopular stance to take and over the next few months fifteen Catholic Worker Houses were forced to close as volunteer workers withdrew their support from the organization.

After the war Day joined with David Dillinger and Abraham Muste to establish the Direct Action magazine in 1945. Dellinger once again upset the political establishment when he criticised the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the 1950s Dorothy Day became involved in the campaign against nuclear weapons. This led to Day being arrested several times for civil disobedience and was imprisoned four times between 1955 and 1959. Day was also involved in the campaign for black civil rights and an end to the Vietnam War. In 1973, aged 75, Day was imprisoned again after taking part in a banned picket line in support of the United Farm Workers in California.

As well as writing over 1,000 articles for the Catholic Worker, Day wrote several books including, Houses of Hospitality (1939), an account of the Catholic Worker movement, an autobiography, The Long Loneliness (1952) and On Pilgrimage: the Sixties (1972).